Ingushetia

Republic of Ingushetia

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: State Anthem of Ingushetia | |

| |

| Coordinates: 43°12′N 45°00′E / 43.200°N 45.000°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | North Caucasian |

| Economic region | North Caucasus |

| Capital | Magas |

| Largest city | Nazran |

| Government | |

| • Type | People's Assembly[1] |

| • Head[1] | Mahmud-Ali Kalimatov[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,628 km2 (1,401 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | |

| • Rank | 74th |

| • Density | 163.16/km2 (422.6/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 54.8% |

| • Rural | 45.2% |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK[5]) |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-IN |

| Vehicle registration | 06 |

| Official language(s) | Ingush[6] • Russian[7] |

| Website | ingushetia.ru |

Ingushetia or Ingushetiya,[8][a] officially the Republic of Ingushetia,[b] is a republic of Russia located in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe. The republic is part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; and borders the Russian republics of North Ossetia–Alania to its west and north and Chechnya to its east and northeast.

Its capital is the town of Magas, while the largest city is Nazran. At 3,600 square km, in terms of area, the republic is the smallest of Russia's non-city federal subjects. It was established on 4 June 1992, after the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was split in two.[9][10] The republic is home to the indigenous Ingush, a people of Nakh ancestry. As of the 2021 Census, its population was estimated to be 509,541.[4]

Largely due to the insurgency in the North Caucasus, Ingushetia remains one of the poorest and most unstable regions of Russia. Although the violence has died down in recent years,[11][12] the insurgency in neighboring Chechnya had occasionally spilled into Ingushetia. According to Human Rights Watch in 2008, the republic has been destabilized by corruption, a number of high-profile crimes (including kidnapping and murder of civilians by government security forces),[13] anti-government protests, attacks on soldiers and officers, Russian military excesses and a deteriorating human rights situation.[14][15] In spite of this, Ingushetia has the highest life expectancy in all of Russia at 80.52, beating out second-place Dagestan by almost 4 years.

Etymology

[edit]The name Ingushetia (Ингушетия) derives from the Russian name of the Ingush, which in turn is derived from the ancient Ingush village Angusht, and from the Georgian suffix -éti.[16] The name in Ingush is Ghalghaaichie (Гӏалгӏайче, /ʁalʁaitʃe/).[17]

In the 1920–1930s there was not yet a unifying name for the Ingush Autonomous Oblast. Although the oblast was officially called Ingushetia, some scientists like Nikolai Yakovlev and Leonid Semyonov insisted that its correct name is Ingushiya (Ингушия).[18]

History

[edit]Historical overview

[edit]

10,000–8000 BC

6000–4000 BC

4000–3000 BC

20 BC

900–1200 AD

1239 AD

1300–1400 AD

1558 AD

1562 AD

In Caucasian War and as part of Terek Cossacks Okrug

[edit]In the 18th century the Ingush were mostly pagan and Christian, with a Muslim minority. Beginning in 1588 some Chechen societies joined Russia (Shikh Okotsky; Albir-Murza Batayev). Russian historians claim that the Ingush volunteered to become a part of Russia. This assertion is mostly based on the document signed on 13 June 1810 by General-Major Delpotso and representatives of two Ingush clans; most other clans resisted the Russian conquest. In 1811, at the Tsar's request, Moritz von Engelhardt, a Russian envoy of German origin visited the mountainous region of Ingushetia and tried to induce the Ingush people to join Russia, promising many benefits offered by the Tsar. The representative of the Ingush people rejected the proposal with the reply: "Above my hat I see only sky". This encounter was later used by Goethe in his 1815 poem, "Freisinn" ('free spirit').[30][31]

On 29 June 1832, the Russian Baron Rozen reported in letter No.42 to count Chernishev that "on the 23rd of this month I exterminated eight Ghalghaj (Ingush) villages. On the 24th I exterminated nine more villages near Targim." By 12 November 1836 (letter no.560), he claimed that highlanders of Dzheirkah, Kist, and Ghalghaj had been at least temporarily subdued.[32] In 1829 Imam Shamil began a rebellion against Russia. He conquered Dagestan, Chechnya, and then attacked Ingushetia hoping to convert the Ingush people to Islam, thus gaining strategic allies. However, the Ingush defeated Imam Shamil's forces. They successfully repulsed two more attempts in 1858. Nevertheless, locked in warfare with two strong opponents and their allies, Ingush forces were eventually devastated. According to the Russian officer Fedor Tornau, who fought with the aid of Ossetian allies against the Ingush, the Ingush had no more than six hundred warriors.[33] However, the Russian conquest in Ingushetia was extremely difficult and the Russian forces began to rely more upon methods of colonization: extermination of the local population and resettlement of the area with Cossack and Ossetian loyalists.

The colonization of Ingush land by Russians and Ossetians began in the mid-19th century. The Russian General Evdokimov and Ossetian colonel Kundukhov in 'Opis no. 436' "gladly reported" that "the result of colonization of Ingush land was successful".

Renamed Ingush villages and towns:[34]

- Ghazhien-Yurt was renamed Stanitsa Assinovskaya in 1847.

- Ebarg-Yurt was renamed Stanitsa Troitskaya in 1847.

- Dibir-Ghala (town) was renamed Stanitsa Sleptsovskaya in 1847.

- Magomet-Khite was renamed Stanitsa Voznesenskaya in 1847.

- Akhi-Yurt was renamed Stanitsa Sunzhenskaya in 1859.

- Ongusht was renamed Stanitsa Tarskaya in 1859.

- Ildir-Ghala (town) was renamed Stanitsa Karabulakskaya in 1859.

- Alkhaste was renamed Stanitsa Feldmarshalskaya in 1860.

- Tauzen-Yurt was renamed Stanitsa Vorontsov-Dashkov in 1861.

- Sholkhi was renamed Khutor Tarski in 1867.

Following Imam Shamil's repeated losses by the end of the Caucasian War, the Russians and Chechens unified their forces. Former Chechen rebels and their men joined the Russian ranks. On 3 November 1858, General Evdokimov ordered (order N1896) a former rebel commander, naib Saib-Dulla Gekhinski (Saadulla Ospanov) of Chechnya to attack and destroy Ingush settlements near the Assa and Fortanga rivers: Dattikh, Meredzhi, Aseri, Shagot-Koch and others.[35] After their defeats in combat, the remaining Ingush clans resorted mostly to underground resistance.[36]

The Russians built the fortress Vladikavkaz ("ruler of the Caucasus") on the place of Ingush village of Zaur.[37] Russian General Aleksey Petrovich Yermolov wrote in a letter to the Tsar of Russia, "It would be a grave mistake for Russia to alienate such a militaristic nation as the Ingush." He suggested the separation of the Ingush and Chechens in order for Russia to win the war in the Caucasus. In another letter from General Ermolov to Lanski (dated 12 January 1827) on the impossibility of forceful Christianization of the Ingush, Yermolov wrote: "This nation, the most courageous and militaristic among all the highlanders, cannot be allowed to be alienated ..."

The last organized rebellion (the so-called "Nazran insurrection") in Ingushetia occurred in 1858 when 5,000 Ingush launched an attack against Russian forces, but lost to the latter's superior number. The rebellion signaled the end of the First Russo-Caucasian War. In the same year, the Tsar encouraged the emigration of Ingush and Chechens to Turkey and the Middle East by claiming that "Muslims need to live under Muslim rulers". His apparent motivation was to depopulate the area for the settlement of Ossetians and Cossacks.[36] Some Ingush became exiled to deserted territories in the Middle East where many of them died. The remainder were Culturally assimilated by Russification. It was estimated that eighty per cent of the Ingush had left Ingushetia for the Middle East by 1865.[38][39]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Soviets promised the Ingush that the villages and towns annexed during the colonization would be returned to the Ingush. Ingushetia became a major battleground between the old archenemies: general Denikin, and Ingush resistance fighters. In his memoirs, general Denikin wrote [40]

"Ingush people are the least numerous, most welded, and strongly martial organization. They were, in essence, the supreme arbiter of the North Caucasus. The moral of the appearance was defined long ago in Russian text-books of geography, "the chief occupation – animal husbandry and robbery ..." The last one of the two reached special art in the society. Political aspirations came from the same trend. The Ingush are mercenaries of the Soviet regime, they support it but don't let the spread of it in their province. At the same time, they tried to strike up relations with Turkey and sought the assistance from the Turks from Elisavetpol, and Germany – from Tiflis. In August, when the Cossacks and Ossetians captured Vladikavkaz, the Ingush intervened and saved the Soviet Board of Commissioners of Terek, but sacked the city and captured the state bank and mint. They robbed all the neighbors: the Cossacks and Ossetians in the name of "correcting historical errors" for a shortage of land, the Bolsheviks – in return for their services, Vladikavkaz citizens – for their helplessness, and the Kabardins – just out of habit. They were hated by everyone, and they did their "craft" in unison, well organized, in a big way, becoming the richest tribe in the Caucasus."

— Anton Denikin, Essays on the Russian Troubles (1925)

As part of the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus

[edit]On 21 December 1917 Ingushetia, Chechnya, and Dagestan declared independence from Russia and formed a single state called the "United Mountain Dwellers of the North Caucasus" (also known as Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus), which was recognized by Central Powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary and Turkey), Georgia, and Azerbaijan (which declared their independence from Russia in 1918) as an independent state.[41] For example, Anna Zelkina writes that in May 1918 the first country to recognize independence was Turkey:[42]

The First Congress of the North Caucasus formed a Provisional Government of the North Caucasian Free State (SeveroKavkazskoye Svobodnoye Gosudarstvo) and in May 1918 declared the establishment of the North Caucasian Republic. The only country to recognize it was Turkey.

Later Germany and others followed the recognition. According to P. Kosok:[43]

Azerbaidzhan and Armenia (May 28, 1918). All three states then concluded independent treaties with Turkey, which similarly acknowledged the independence of the Northern Caucasus and concluded a treaty of friendship with it on June 8, 1918. An exchange of diplomatic notes then took place between the head of the German Extraordinary Delegation, General von Lossov, and the North Caucasian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bammat, resulting in the de facto recognition by Germany of the independence of the Northern Caucasus.

According to the British War Office, Germans tried to establish the military base in Ingushetia:[44]

...the German Command with the object of securing the presence of German regiments within Ingush territory. The Ingushi declare that all attempts of any foreign armed force to enter into the Terek region will be regarded by the Ingushi as an attack upon themselves, and the Ingushi will oppose all their forces to such attempts.

The capital of the new state was moved to Temir-Khan-Shura (Dagestan).[45][46][47] The first prime minister of the state was elected Tapa Chermoyev, a Chechen prominent statesman; the second prime minister was Ingush statesman Vassan-Girey Dzhabagiev who also was the author of the Constitution of the land in 1917. In 1920 he was reelected for a third term. In 1921 Russians attacked and occupied the country and forcefully merged it with the Soviet state. The Caucasian war for independence continued and the government went into exile.[48]

As part of Chechen-Ingush ASSR

[edit]Cossack General Andrei Shkuro in his book writes:[49]

Ingushetia was the most unanimous and entirely Bolshevik. Ever since the conquest of the Caucasus, the brave and freedom-loving Ingush, who were desperately defending their independence, were partly exterminated and partly driven into barren mountains. The Terek Cossacks were settled on the fertile lands that had belonged to them, and Cossacks founded their villages on the wedge that had cut into Ingushetia. Deprived of the opportunity to earn their bread in an honest way, the Ingush lived by robbery and raids on the Cossack lands. Even in peacetime, the Terek Cossacks bordering Ingush did not go to the field without rifles. Not a day went by without shooting and bloodshed. Considering the Cossacks as oppressors, and the Cossack lands were still theirs, the Ingush mercilessly took revenge on them. The relationship was created completely irreconcilable; further cohabitation was unthinkable. It was necessary either to exterminate the Ingush completely, or to evict the Cossacks from the former Ingush lands, returning those to their former owners.

The Soviets confiscated the remaining Ingush properties by collectivization and dekulakization[50] and unified Chechnya and Ingushetia into Chechen-Ingush ASSR.

During World War II Ingush youth were drafted into the Russian army. In August 1942 Nazi German forces captured half of the North Caucasus within thirty-three days moving from Rostov-On-Don to Mozdok 560 km or almost 17 km per day (see Battle of the Caucasus). From Mozdok to Malgobek same thirty three days, 20 km the German forces moved roughly 600 meters per day and were stopped only at Ordzhonikidze (modern-day Vladikavkaz) and Malgobek which were mostly populated by Ingush before the genocide of 23 February 1944. The fighting for the Malgobek was so intense that the small town was captured and recaptured four times until the Germans finally retreated.

According to the Soviet military newspaper Red Star, after receiving the news about German brutality toward civilians in Kabardino-Balkaria, Ingush people declared Jihad(Gazavat) against Germans. Stalin planned the expansion of the USSR in the south through Turkey. Muslim Chechens and Ingush could become a threat to the expansion.[51] In February 1944 near the end of World War II, Russian Army and NKVD units flooded the Chechen-Ingush ASSR. The maneuvers were disguised as military exercises of the southern district.

Genocide of 1944

[edit]

During World War II, in 1942 German forces entered the North Caucasus. For three weeks Germans captured over half of the North Caucasus. They were only stopped at two Chechen-Ingush cities: Malgobek and Ordzhonikidze (a.k.a. "Vladikavkaz") by heroic resistance of natives of Chechen-Ingush ASSR.[52] On 23 February 1944, Ingush and Chechens were falsely accused of collaborating with the Nazis, and the entire Ingush and Chechen populations were deported to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Siberia in Operation Lentil, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, while the majority of their men were fighting on the front. The initial phase of the deportation was carried out on American-supplied Studebaker trucks specifically modified with three submachine gun-nest compartments above the deported to prevent escapes. American historian Norman Naimark writes:[53][54][55]

Troops assembled villagers and townspeople, loaded them onto trucks – many deportees remembered that they were Studebakers, fresh from Lend-Lease deliveries over the Iranian border – and delivered them at previously designated railheads. ...Those who could not be moved were shot. ...[A] few fighters aside, the entire Chechen and Ingush nations, 496,460 people, were deported from their homeland.[56]

The deportees were gathered on the railroad stations and during the second phase transferred to the cattle railroad carts. Up to 30% of the population perished during the journey or in the first year of the exile. The Prague Watchdog claims that "in the early years of their exile about half of the Chechens and Ingush died from hunger, cold and disease".[57] The deportation was classified by the European Parliament in 2004 as genocide.[58] After the deportation Ingush resistance against the Soviets began again. Those who escaped the deportation, including shepherds who were high in the mountains during the deportations, formed rebel groups which constantly attacked Russian forces in Ingushetia. Major rebel groups were led by Akhmed Khuchbarov, the Tsitskiev brothers, and an Ingush female sniper, Laisat Baisarova. The last one of the male Ingush rebels was killed in 1977 by the KGB officers, while Baisarova was never captured or killed.[59] American professor Johanna Nichols, who specializes in Chechen and Ingush philology, provided the theory behind the deportation:[60]

In 1944 the nationalities themselves were abolished and their lands resettled when the Chechen and Ingush, together with the Karachay-Balkar, Crimean Tatars, and other nationalities were deported en masse to Kazakhstan and Siberia, losing at least one-quarter and perhaps half of their population in transit. (The reason, never clarified, seems to have been Stalin's wish to clear all Muslims from the main invasion routes in a contemplated attack on Turkey.)

After return from Central Asia

[edit]

After 13 years of exile, the Ingush were allowed to return to Chechen-Ingushetia (but not to Ordzhonikidze a.k.a. "Vladikavkaz" or the Prigorodny District). Most of Ingushetia's territory had been settled by Ossetians and part of the region had been transferred to North Ossetia. The returning Ingush faced considerable animosity from the Ossetians. The Ingush were forced to buy their homes back from the Ossetians and Russians. These hardships and injustices led to a peaceful Ingush protest in Grozny on 16 January 1973, which was crushed by Soviet troops[61] In 1989, the Ingush were officially rehabilitated along with other peoples that had been subjected to repressions.[62]

Post-Soviet period

[edit]In 1991, when the Chechens declared independence from the Soviet Union to form the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, the Ingush chose to secede from the Chechen-Ingush Republic. This was confirmed with the referendum and in 1992 the Ingush joined the newly created Russian Federation to try to resolve the conflict with Ossetia peacefully, also in the hope that the Russians would return their land as a token of their loyalty.

Ethnic cleansing of 1992

[edit]However, ethnic tensions in North Ossetia which were orchestrated by Ossetian nationalists (per Helsinki Human Right Watch), led to an outbreak of violence in the Ossetian–Ingush conflict in October–November 1992, when another ethnic cleansing of the Ingush population started.[63]

Over 60,000 Ingush civilians were forced from their homes in the Prigorodny District of North Ossetia.[36] As a result of the conflict, pro-Russian general Ruslan Aushev, a decorated war hero from the War in Afghanistan, was appointed by the Russian government as the first president of Ingushetia to stop the spread of the conflict. Partial stability returned under his rule.

First and Second Chechen Wars

[edit]In 1994, when the First Chechen War started, the number of refugees in Ingushetia from both conflicts doubled. According to the UN, for every citizen of Ingushetia, one refugee arrived from Ossetia or Chechnya. This influx was very problematic for the economy, which collapsed after Aushev's success. The second Russo-Chechen war which started in 1999 brought more refugees (at some point there was one refugee for every Ingush citizen: 240,000 from Chechnya plus 60,000 from North Ossetia at the peak in 2000) and misery to Ingushetia. In 2001, Aushev was forced to leave his presidency and was succeeded by Murat Zyazikov, a former KGB general. The situation worsened under his rule. Many young Ingush men were abducted by Russian and Ossetian death squads.[64][65][66][67] according to Human rights watchdogs Memorial[68] and Mashr.[69]

The number of rebel attacks in Ingushetia rose, especially after the number of Russian security forces was tripled. For example, according to a Russian news agency a murder of an ethnic-Russian school teacher in Ingushetia was committed by two ethnic-Russian and ethnic-Ossetian soldiers; Issa Merzhoev the Ingush Police detective who solved the crime was shot at and killed by "unknown" assailants shortly after he had identified the murderer.[70] At least four people were injured when a vehicle exploded on 24 March 2008. An upsurge in violence in these months targeted local police officers and security forces. In January 2008, the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation launched a "counter-terrorism" operation in Ingushetia after receiving information that insurgents had been preparing a series of attacks.[71]

Early in August 2008, the war between Georgia and South Ossetia broke out, in which the Russian Federation subsequently became involved.[72] After the outbreak of the war, there were virtually no more attacks or abductions of Ingush civilians by "unknown" forces. Most of the Russian forces were transferred to North and South Ossetia[73] 31 August 2008 Magomed Yevloyev, the head of Ingush opposition and the owner of the website ingushetiya.ru, was killed by Russian security forces[74] Shortly before the unrecognised opposition group People's Parliament of Ingushetia Mekhk-Kkhel called for the recognition of the Russian semi-autonomous republic's independence, opposition activist Magomed Khazbiyev proclaimed, "We must ask Europe or America to separate us from Russia."[75][76]

On 18 October 2008, a Russian military convoy came under grenade attack and machine gun fire near Nazran. Official Russian reports of the ambush, which has been blamed on local Muslim separatists, said two soldiers were killed and at least seven injured. Reports from Ingush opposition sources suggested as many as forty to fifty Russian soldiers were killed.[77][78]

On 30 October 2008, Zyazikov was dismissed from his office (he himself claimed he resigned voluntarily). On the next day, Yunus-Bek Yevkurov was nominated by Dmitry Medvedev and approved as President by the People's Assembly of Ingushetia (later the title President was renamed Head). This move was endorsed by major Russian political parties and by the Ingush opposition.[79][80] Under the current rule of Yevkurov, Ingushetia seems much calmer, showing some semblance of the Russian government. Attacks on policemen have fallen by 40% and abductions by 80%.[81]

Military history

[edit]According to professor Johanna Nichols, in all the recorded history and reconstructable prehistory, the Ingush people have never undertaken battle except in defense.[36] In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC Pharnavaz, his son Saurmag the Iberian kings, and the relatives of Ingush people per Leonti Mroveli, received military assistance from Ingush people in defense of Iberia against the Kartli occupation.[82]

During World War I, 500 cavalrymen from an Ingush regiment of the Wild Division attacked the German Iron Division. The Russian Emperor Nicholas II, assessing the performance of the Ingush and Chechen regiments during the Brusilov breakthrough on the Russian-German front in 1915 wrote in a telegram to the Governor-General of the Tersky region Fleisher:[83]

The Ingush regiment pounced upon the German "Iron Division" like an avalanche. It was immediately supported by the Chechen regiment. The Russian history, including the history of our Preobrazhensky regiment, does not know a single instance of a horse cavalry attacking an enemy force armed with heavy artillery: 4.5 thousand killed, 3.5 thousand taken prisoner, 2.5 thousand wounded. Less than in an hour and a half the "Iron Division" ceased to exist, the division that had aroused fear in the best armies of our allies. On behalf of me, the royal court and the whole of the Russian army send our best regards to fathers, mothers, sisters, wives and brides of those brave sons of the Caucasus whose heroism paved the way for the destruction of German hordes. Russia bows low to the heroes and will never forget them. I extend my fraternal greetings, Nicholas II, August 25, 1915.

In 1994–1996 Ingush volunteers fought alongside Chechens in the First Chechen War. Aside from a few incidents (including the killings of Ingush civilians by Russian soldiers), Ingushetia was largely kept out of the war by a determined policy of non-violence pursued by President Ruslan Aushev.[36]

This changed after the beginning of the Second Chechen War, and especially since Murat Zyazikov became the second Russian appointed president of Ingushetia in 2002. The first major rebel attack of the conflict, in which a military convoy was destroyed occurred in May 2000 and caused the deaths of 19 soldiers. In the June 2004 Nazran raid, Chechen and Ingush rebels attacked government buildings and military bases across Ingushetia, resulting in the deaths of at least 90 Ingush people and an unknown number of Russian troops. Among them the Republic's acting interior minister Abukar Kostoyev, his deputy Zyaudin Kotiyev. In response to a sharp escalation in attacks by insurgents since the summer of 2007,[84] Moscow sent in an additional 25,000 MVD and FSB troops, tripling the number of special forces in Ingushetia.

Resistance

[edit]

- 1800s–1860s: Insurgency against Russian conquest.

- 1860s–1890s: Raids of Ingush abreks on the Georgian Military Highway and Mozdok.

- 1890s–1917: Insurgency of Ingush resistance under Chechen abrek Zelimkhan Gushmazukaev and Ingush abrek Sulumbek of Sagopshi, execution of Russian viceroy to Ingushetia colonel Mitnik by Ingush resistance fighter Buzurtanov.

- 1917–1920s: Insurgency of Ingush resistance fighters against combined Russian White Guards, Cossacks, Ossetians, and general Denikin forces.

- 1920s–1930s: Insurgency of Ingush people against Communists, executions of Communist leader of Ingushetia Chernoglaz by Ingush rebel Uzhakhov. Execution of Communist party leader of Ingushetia Ivanov by Ingush rebels.

- 1944–1977: Ingush rebels avenging the deportation of the Ingush nation. Scores of Russian army units and NKVD, KGB officers killed.

- 1992: Ossetian-Ingush conflict. In combat operations Ingush rebels capture armor which later transferred to Chechens or given back to Russian army after the conflict ended.

- 1994: Nazran. Ingush civilians stop Russian army, flip armor, burn military trucks which were on the march to Chechnya in Russian-Chechen war. First Russian casualties reported from hands of Ingush rebels.

- 1994–1996: Ingush rebels defend Grozny and participate in combat operations on Chechen side.

- 1999–2006: Ingush rebels join Chechen rebels, the independence war turns into Jihad.

- 13 July 2001: Ingush people protest "defiling and desecration" of historical Christian Ingush church Tkhaba-Yerdy after Russian troops made the church into a public toilet. Though Ingush are Muslims they highly respect their Christian past.[85]

- 15 September 2003: Ingush rebels use bomb truck and attack FSB headquarters in Maghas. Several dozens of Russian FSB officers killed including the senior officer overseeing the FSB in Chechen republic. The several story HQ building is severely damaged.[86]

- 6 April 2004: Ingush rebels attack Russian appointed president of Ingushetia Murat Zyazikov. He was wounded when a car bomb was rammed into his motorcade.

- 22 June 2004: Chechen and Ingush rebels raid on Russian troops in Ingushetia. Hundreds of Russian troops killed.

- 10 July 2006: In the night, Chechen politician and leader of the militants Shamil Basayev and other four militants were killed in the village of the Ekazhevo during a truck explosion.

- 31 August 2008: Execution of Magomed Yevloyev Ingush dissident, journalist, lawyer, businessman, and the owner of the news website Ingushetiya.ru, known for being highly critical of Russian regime in Ingushetia. He was shot in the temple.[87] Awarded posthumously, and his name is engraved in stone on the monuments at the Journalists' Memorials in Bayeux, France and Washington D.C., the United States.[88]

- 30 September 2008: A suicide bomber attacked the motorcade of Ruslan Meiriyev, Ingushetia's top police official.

- 10 June 2009: Snipers killed Aza Gazgireyeva, deputy chief justice of the regional Supreme Court, as she dropped her children off at school. Russian news agencies also cited investigators as saying she was likely killed for her role in investigating the 2004 attack on Ingush police forces by Chechen fighters.[89]

- 13 June 2009: Two gunmen sprayed former deputy prime minister Bashir Aushev with automatic-weapon fire as he got out of his car at the gate outside his home in the region's main city, Nazran.[90]

- 22 June 2009: Russian appointed president of Ingushetia Yunus-Bek Yevkurov was badly hurt when a suicide bomber detonated a car packed with explosives as the president's convoy drove past. The attack killed three bodyguards.[91]

- 12 August 2009: Gunmen killed construction minister Ruslan Amerkhanov in his office in the Ingush capital, Magas.[92]

- 17 August 2009: A suicide bomber killed 21 Ingush police officers and unknown numbers of Russian Internal Ministry troops which were stationed in Nazran, after he drove a truck full of explosives into a MVD police base.

- 25 October 2009: Execution of Maksharip Aushev, an Ingush businessman, dissident, and a vocal critic of Russian regime policies in Ingushetia. His body had over 60 bullet holes. Awarded posthumously by the U.S. Department of State in 2009.[93]

- 2 March 2010: Another militant has been killed in the village of the Ekazhevo, his name is Said Buryatsky, but his real one is Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Tikhomirov, although he was born in Republic of Buryatia.

- 5 April 2010: A suicide bomber injured three police officers in the town of Karabulak. Two officers died at the hospital as a result of their injuries. While investigators arrived on scene, another car bomb was set off by remote. Nobody was hurt in the second blast.[94]

- 24 January 2011: A suicide bomber, Magomed Yevloyev (same first and last name as the slain Ingush opposition journalist Magomed Yevloyev), killed 37 people at Domodedovo airport, Moscow, Russia.

- 2012: Ingush rebels participate in the war against Bashar al-Assad, Iranian, and Russian advisors in Syria, which is largely viewed by Ingush rebels as a war against Russia and the Iranian-speaking Ossetians. The rebel Ingush commanders are veterans of Ossetian-Ingush conflict, wars in Chechnya, Daud Khalukhayev from the Ingush village of Palanazh (Katsa), and a descendant of Ingush deportee of 1860s Syrian-born Walid Didigov.[95][96]

- 6 June 2013: Accusation of former Ingush rebel leader Ali "Maghas" Taziev in Rostov-On-Don regional Russian court, who was captured after he voluntarily gave himself in on 9 June 2010 to Russian forces in Ingushetia on the agreement that Russians will liberate his relatives held hostage in one of the Russian military bases.

- 27 August 2013: Execution of the head of security of Ingushetia Akhmet Kotiev and his bodyguard by Ingush rebels. Kotiev was actively involved in the assassination of Magomed Yevloyev.

- 10 December 2013: Ingush opposition leader Magomed Khazbiev, who was a close friend of assassinated Magomed Yevloyev, attends Euromaidan in Ukraine and participates in anti-Russian campaign there[clarification needed], after which his parents were threatened and harassed in Russia. On his website he wrote: "the fact that Putin's slaves harass my parents does not make any sense [is in vain], if you [Russians] want me to stop you have to kill me like Magomed Yevloyev and Makhsharip Aushev".[97]

- 2 February 2014: Russian FSB officially claimed that in December 2013 four North Caucasian instructors operated in Ukraine, and prepared Ukrainians for "street battles against Russian interests".[98]

- 20 April 2014: Famous Ingush human rights defender Ibragim Lyanov stated that Ingushetia wants to separate from Russia and become an independent state, using the example of the Crimean separation from Ukraine.[99]

- 24 May 2014: Ingush rebel leader Arthur Getagazhev, four rebels, and two civilians were killed in action in the village of Sagopshi by Russian forces.[100]

- 2 July 2014: After several months of denial, pro-Russian president of Ingushetia finally recognizes that there are Ingush people fighting in Ukraine on "both sides".[101]

- 2 July 2014: Ingush rebels attack Russian armored military convoy killing one and wounding seven soldiers.[102]

- 6 July 2014: Russian special forces prepared an ambush near the morgue in Nazran hospital where the body of Arthur Getagazhev was located. The intelligence reported that Ingush rebels will try to recover the body of the slain leader. The intelligence was correct. Radio Free Europe (section specializing in the Caucasus), reports that in the middle of the day two Ingush rebels attacked the ambush, according to unofficial source two rebels killed seven and wounded four Russian FSB and spetsnaz officers in less than forty seconds, after which the rebels left the scene unharmed. The source in Ingush police who wanted to stay anonymous said that exact number of killed are known only by the FSB but nobody would dare to declare it officially.[103] According to pro-Kremlin LifeNews, released video of the attack lasted less than 19 seconds.[104]

- 17 January 2015: Maghas. Rise of anti-Western sentiments. Over 20,000 Ingush citizens protest against Europe.[105][106]

- 28 February 2015: Russian opposition leader Nemtsov's death linked to Ingushetia by Russian police.[107]

- 26 March 2019: Thousands of people in Ingushetia have protested against a controversial border deal with neighboring Chechnya, denouncing land swaps under the agreement and calling for Ingushetia head Yunus-Bek Yevkurov to step down.

- 25 June 2019: Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, has announced his resignation after almost 11 years in the position. De facto Ingushetia has no active leader. Civil protests continue, Ingush people boycotting the Russian appointed elections.

- 2 March 2024: Clashes between militants and the Russian police began in Ingushetia.

Politics

[edit]Up until the dissolution of the Soviet state, Ingushetia was part of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic. In the late 1920s – early 1930s the Soviet officials were eager to enforce the Chechen-Ingush merger as an "objective" and "natural" process. The Soviet linguist Nikolay Yakovlev, who was a supporter of the merger, suggested that an inclusive name of "Veinakh" ("our people") had to be used for both the Chechens and Ingush. According to his views, the rapid urbanization and rapprochement of the Chechens and Ingush within one and the same republic might encourage the formation of a common culture and language and the establishment of a unified "Veinakh" people.

During the late '80s, together with the separatist tendencies across the Soviet Union, the Second Congress of the Ingush People was held in Grozny on 9–10 September 1989. The gathering was directed at the top leadership of the Soviet Union, and included a request to "restore the Ingush people's autonomy within their historical borders, the Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic with a capital in the right-bank part of the city of Ordzhonikidze". The Ingush Republic was to be organized out of six traditional Ingush districts (including the contested Prigorodny District). The rise of the Russian Federation - and the 1991 Chechen Revolution - gave the Ingushetians the independence they vowed for and in 1992 the remainder of Checheno-Ingushstia became thus the Republic of Ingushtia. During the 1990s, Ingushetia was ruled by its elected president Ruslan Aushev, a former Soviet general and hero of the war in Afghanistan.

The head of government and the highest executive post in Ingushetia is the Head, elected by representatives of the Parliament of Ingushetia.

Recent heads:

- Ruslan Aushev: 10 November 1992 (Head of the Republic until 7 March 1993) – 28 December 2001

- Akhmed Malsagov (interim): 28 December 2001 – 23 May 2002

- Murat Zyazikov: 23 May 2002 – 30 October 2008[108]

- Yunus-Bek Yevkurov: 30 October 2008 – 26 June 2019

- Makhmud-Ali Kalimatov: 26 June 2019–present

Recent Chairmen of the Government:

- Ruslan Tatiyev: 24 March 1993 – 5 July 1993

- Tamerlan Didigov: 5 July 1993 – 21 March 1994

- Mukharbek Didigov: 21 March 1994 – 9 December 1996

- Belan Khamchiyev: 10 December 1996 – 3 August 1998

- Magomed-Bashir Darsigov: 3 August 1998 – 24 November 1999

- Akhmed Malsagov: 24 November 1999 – 14 June 2002

- Viktor Aleksentsev: 26 August 2002 – 3 June 2003

- Timur Mogushkov: 3 June 2003 – 30 June 2005

- Ibragim Malsagov: 30 June 2005 – 13 March 2008

- Kharun Dzeytov: 14 March 2008 – 12 November 2008

- Rashid Gaysanov: 13 November 2008 – 5 October 2009

- Aleksey Vorobyov: 5 October 2009 – 10 March 2010

- Musa Chiliyev: 21 March 2011 – 19 September 2013

- Abubakar Malsagov: 19 September 2013 – 18 November 2016

- Ruslan Gagiyev: 18 November 2016 – 9 September 2018

- Zyalimkhan Yevloyev: 9 September 2018 – 8 September 2019

- Konstantin Surikov: 9 September 2019 – 27 January 2020

- Vladimir Slastenin: 26 March 2020–present

The parliament of the Republic is the People's Assembly, composed of 34 deputies elected for a four-year term. The People's Assembly is headed by the Chairman. As of 2022, the Chairman of the People's Assembly is Vladimir Slastenin.

The Constitution of Ingushetia was adopted on 27 February 1994.

Ingushetia is a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

The capital was moved from Nazran to Magas in December 2002.

The most recent election was held in 2013.

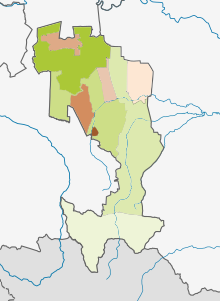

Administrative divisions

[edit]

- Cities under republic's jurisdiction (as of 2016):

- Districts:

- Dzheyrakhsky (Джейрахский)

- Sunzhensky (Сунженский)

- Nazranovsky (Назрановский)

- Malgobeksky (Малгобекский)

Demographics

[edit]

Population: 509,541 (2021 Census);[110] 412,529 (2010 Census);[111] 467,294 (2002 Census).[112]

Vital statistics

[edit]- Source: Russian Federal State Statistics Service Archived 14 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

| Average population (× 1000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Total fertility rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 6,889 | 1,867 | 5,022 | 25.3 | 6.8 | 18.4 | ||

| 1996 | 5,980 | 1,958 | 4,022 | 20.9 | 6.8 | 14.0 | ||

| 1997 | 6,055 | 1,957 | 4,098 | 20.6 | 6.7 | 14.0 | ||

| 1998 | 5,929 | 2,064 | 3,865 | 19.8 | 6.9 | 12.9 | ||

| 1999 | 6,624 | 1,953 | 4,671 | 20.6 | 6.1 | 14.6 | ||

| 2000 | 8,463 | 2,117 | 6,346 | 21.5 | 5.4 | 16.2 | ||

| 2001 | 8,753 | 1,875 | 6,878 | 19.4 | 4.2 | 15.3 | ||

| 2002 | 7,578 | 1,874 | 5,704 | 16.4 | 4.1 | 12.4 | ||

| 2003 | 7,059 | 1,785 | 5,274 | 15.3 | 3.9 | 11.4 | ||

| 2004 | 6,794 | 1,751 | 5,043 | 15.0 | 3.9 | 11.1 | ||

| 2005 | 6,777 | 1,821 | 4,956 | 15.2 | 4.1 | 11.1 | ||

| 2006 | 7,391 | 1,830 | 5,561 | 16.9 | 4.2 | 12.7 | ||

| 2007 | 8,284 | 1,625 | 6,659 | 19.3 | 3.8 | 15.5 | ||

| 2008 | 9,215 | 1,561 | 7,654 | 21.8 | 3.7 | 18.1 | ||

| 2009 | 9,572 | 1,877 | 7,695 | 22.9 | 4.5 | 18.4 | 2.51 | |

| 2010 | 11,178 | 1,857 | 9,321 | 27.1 | 4.5 | 22.6 | 2.99 | |

| 2011 | 414 | 11,408 | 1,705 | 9,703 | 27.0 | 4.0 | 23.0 | 2.94 |

| 2012 | 430 | 9,350 | 1,595 | 7,755 | 21.4 | 3.7 | 17.7 | 2.27 |

| 2013 | 442 | 9,498 | 1,568 | 7,930 | 21.2 | 3.5 | 17.7 | 2.23 |

| 2014 | 453 | 9,858 | 1,586 | 8,272 | 21.5 | 3.5 | 18.0 | 2.28 |

| 2015 | 463 | 8,647 | 1,557 | 7,090 | 18.5 | 3.3 | 15.2 | 1.97 |

| 2016 | 472 | 7,750 | 1,555 | 6,195 | 16.3 | 3.3 | 13.0 | 1.75 |

| 2017 | 480 | 7,890 | 1,554 | 6,336 | 16.3 | 3.2 | 13.1 | 1.77 |

| 2018 | 488 | 8,048 | 1,548 | 6,500 | 16.3 | 3.1 | 13.2 | 1.79 |

| 2019 | 497 | 8,252 | 1,529 | 6,723 | 16.4 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 1.83 |

| 2020 | 507 | 8,463 | 1,891 | 6,572 | 16.6 | 3.7 | 12.9 | 1.85 |

| 2021 | 513 | 8,480 | 2,194 | 6,286 | 16.3 | 4.2 | 12.1 | 1.87 |

| 2022 | 7,912 | 1,727 | 6,185 | 15.0 | 3.3 | 11.7 | 1.83 | |

| 2023 | 7,844 | 1,705 | 6,139 | 15.0 | 3.3 | 11.7 | 1.81 |

Note: Total fertility rate 2009, 2010, 2011 source:[113]

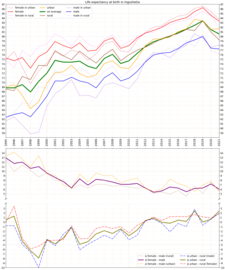

Life expectancy

[edit]Ingushetia has life expectancy noticeably higher than in any other federal subjects of the Russian Federation.[114][115] In such way, Ingushetia is a Russian "blue zone". In the pre-pandemic 2019, life expectancy in Ingushetia was the same as in Switzerland, according to estimation of WHO, — 83.4 years.

| 2019 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Average: | 83.4 years | 80.5 years |

| Male: | 80.0 years | 77.3 years |

| Female: | 86.3 years | 83.3 years |

-

Life expectancy at birth in Ingushetia

-

Life expectancy with calculated differences

-

Life expectancy in Ingushetia in comparison with other regions of the North Caucasus

-

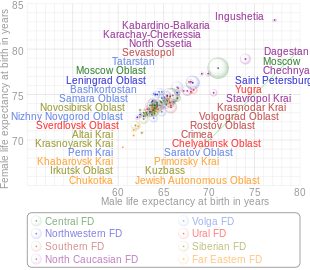

Interactive chart of comparison of male and female life expectancy for 2021. Open the original svg-file in a separate window and hover over a bubble to highlight it.

-

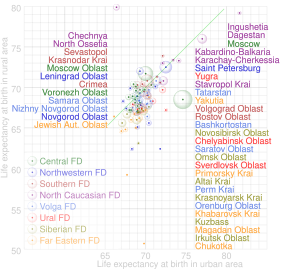

Analogious interactive chart of comparison of urban and rural life expectancy.

Original interactive file.

Ethnic groups

[edit]

According to the 2021 Russian census,[4] ethnic Ingush make up 96.4% of the republic's population. The Ingush, a nationality group indigenous to the Caucasus, mostly inhabit Ingushetia. They refer to themselves as Ghalghaj (from Ingush: Ghala ('fortress' or 'town') and ghaj ('inhabitants' or 'citizens'). The Ingush speak the Ingush language, which has a very high degree of mutual intelligibility with neighboring Chechen.

Other groups include Chechens (2.5%), Russians (0.7%), and a host of smaller groups, each accounting for less than 0.5% of the total population.[116]

| Ethnic group |

1926 Census | 1939 Census | 1959 Census | 1970 Census | 1979 Census | 1989 Census | 2002 Census | 2010 Census | 2021 Census1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Ingush | 47,280 | 61.6% | 79,462 | 58.0% | 44,634 | 40.6% | 99,060 | 66.0% | 113,889 | 74.2% | 138,626 | 74.5% | 361,057 | 77.3% | 385,537 | 94.1% | 473,440 | 96.4% |

| Chechens | 2,553 | 3.3% | 7,746 | 5.7% | 5,643 | 5.1% | 8,724 | 5.8% | 9,182 | 6.0% | 19,195 | 10.3% | 95,403 | 20.4% | 18,765 | 4.6% | 12,240 | 2.5% |

| Russians | 24,185 | 31.5% | 43,389 | 31.7% | 51,549 | 46.9% | 37,258 | 24.8% | 26,965 | 17.6% | 24,641 | 13.2% | 5,559 | 1.2% | 3,321 | 0.8% | 3,294 | 0.7% |

| Ukrainians | 1,501 | 2.0% | 1,921 | 1.4% | 1,763 | 1.6% | 1,068 | 0.7% | 687 | 0.4% | 753 | 0.4% | 189 | 0.0% | 91 | 0.0% | 34 | 0.0% |

| Others | 1,215 | 1.6% | 4,549 | 3.3% | 6,438 | 5.9% | 3,978 | 2.7% | 2,852 | 1.9% | 2,781 | 1.5% | 5,086 | 1.1% | 1,918 | 0.5% | 2,129 | 0.4% |

| 1 18,404people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[117] | ||||||||||||||||||

Religion

[edit]

Ingushetia is one of the most religious regions of Russia.[119] The Ingush people predominantly follow the Shafi'i Madhhab of Sunni Islam[120] with strong influence from Sufism, which is often associated with one of two traditional Sufi orders: the Sufi tariqa Naqshbandi, represented in Ingushetia by the brotherhood of Deni Arsanov, and the tariqa Qadiriyyah, associated with Kunta-Haji Kishiev.[121][122]

Education

[edit]Ingush State University, the first institute of higher education in the history of Ingushetia, was founded in 1994 in Ordzhonikidzevskaya.[123]

Geography

[edit]

Ingushetia is situated on the northern slopes of the Caucasus. Its area is reported by various sources as either 2,000 square kilometers (770 sq mi)[124] or 3,600 square kilometers (1,400 sq mi);[125] the difference in reporting is mainly due to the inclusion or exclusion of parts of Sunzhensky Districts. The republic borders North Ossetia–Alania (SW/W/NW/N), the Chechnya (NE/E/SE), and the country of Georgia (Mtskheta-Mtianeti) (southwards). The highest point is the Gora Shan[126] (4451 m).

A 150-kilometer (93 mi) stretch of the Caucasus Mountains runs through the territory of the republic.

Rivers

[edit]

Major rivers include:

Natural resources

[edit]Ingushetia is rich in marble, timber, dolomite, plaster, limestone, gravel, granite, clay, thermal medical water, rare metals, mineral water, oil (over 60 billion tons), and natural gas reserves.

Climate

[edit]Ingushetia's climate is mostly continental.

- Average January temperature: −10 °C (14 °F)

- Average July temperature: 21 °C (70 °F)

- Average annual precipitation: 450–650 mm (18–26 in)

- Average annual temperature: +10 °C (50 °F)

Economy

[edit]There are some natural resources in Ingushetia: mineral water in Achaluki, oil and natural gas in Malgobek, forests in Dzheirakh, metals in Galashki. The local government is considering the development of tourism; however, this is problematic due to the uneasy situation in the republic itself and the proximity of some conflict zones. However, Ingushetia continues to remain as one of Russia's poorest republics, largely due to the ongoing conflict, corruption and civil disorders. Unemployment is estimated to be around 53%, and growing poverty is a major issue.[127]

Notable people

[edit]- Yunus-bek Yevkurov, deputy Defense Minister of the Russian Federation.

- Musa Evloev, Greco-Roman wrestler. He is a two-time world champion, Olympic champion, and two-time national champion,

- Movsar Evloev, #6 Ranked UFC Featherweight.[128]

- Idris Bazorkin, writer.[129]

- Ruslan Aushev, infantry general, Hero of the Soviet Union, first president of Ingushetia.

- Rakhim Chakkhiev, boxer.[130]

- Issa Kodzoev, writer.[131]

- Issa Kostoyev, policeman who captured serial killer Andrei Chikatilo.[132]

- Nazyr Mankiev, wrestler.[133]

- Murad Ozdoev, WWII fighter pilot and recipient of the title Hero of the Russian Federation.

- Sulom-Beck Oskanov, Air Force general.

- Islam Timurziev, boxer.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˌɪŋɡʊˈʃɛtiə/ ING-guu-SHET-ee-ə; Ingush: ГӀалгӏайче, romanized: Ghalghajče; Russian: Ингуше́тия, IPA: [ɪnɡʊˈʂetʲɪjə].

- ^ Also referred as Ingush Republic. Ingush: Гӏалгӏай Мохк, romanized: Ghalghaj Moxk; Russian: Респу́блика Ингуше́тия, romanized: Respúblika Ingushétiya.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Constitution of the Republic of Ingushetia, Article 64

- ^ Official website of the Republic of Ingushetia. Head of the Republic of Ingushetia Archived 10 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (21 May 2004), "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)", Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian), Federal State Statistics Service, archived from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 1 November 2011

- ^ a b c "Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Всероссийская перепись населения. Federal State Statistics Service (Russia). Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Ingushetia, Article 14

- ^ Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Law of 4 June 1992

- ^ Official website of the Republic of Ingushetia. Social-Economic Characteristics Archived 2 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "Russia's North Caucasus Insurgency Widens as ISIS' Foothold Grows". www.worldpoliticsreview.com. 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

Russia's North Caucasus insurgency has gone relatively quiet, but reduced casualty numbers belie a still-worrying situation where long-standing grievances remain.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (4 April 2017). "Why suspicion over St Petersburg metro attack is likely to fall on Islamist groups". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

A renewed crackdown on any suspected militant activity in the run-up to the Sochi winter Olympics in 2014 and the departure of many militants to fight in Syria led to a weakening of the North Caucasus insurgency.

- ^ "Ingushetia's cycle of violence". BBC. 3 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ sk/HRW/acb93ad76de9628c932576501538c803.htm Urgent Need for Vigorous Monitoring in the North Caucasus. Human Rights Watch/Reuters, 15 April 2008. (archive link)

- ^ People & Power – Ingushetia: A second Chechnya – 28 October 2009, Al Jazeera English on YouTubeAl Jazeera English on YouTube [dead link]

- ^ Nichols 1997.

- ^ Nichols & Sprouse 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Shnirelman 2006, p. 209.

- ^ Wuethrich, Bernice (2000). "Peering Into the Past, with Words". Science. 288 (5469): 1158. doi:10.1126/science.288.5469.1158. S2CID 82205296. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ a b N.D. Kodzoev. History of Ingush nation.

- ^ The Land of the Czar. Wahl. 1875. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Reise durch Russland nach dem kaukasischen Isthmus. Karl Koch. 1843. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Algemeen aardrijkskundig woordenboek volgens de nieuwste staatkundige veranderingen, en de laatste, beste en zekerste berigten. Jacobus van Wijk. 1821. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Броневский, Семен (20 July 2017). Новѣйшия географическия и историческия извѣстия о Кавказѣ. В Тип. С. Скливановскаго. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Авторские Материалы". Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ D.V.Zayats (2001). "Maghas – "The Sun City" – New Capital of Ingushetia". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Аланский историк из чеченцев". Chechenews.com. 29 August 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Категория: Мировая история. "Аланский историк". 95live.ru. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ a b История ингушского народа. Глава 4. "История ингушского народа. Глава 4. ГЛАВА 4 ИНГУШЕТИЯ В XV-XVIII ВВ. § 1. Жизнь ингушей на равнинах и в горах На равнинах Ингушетииaccess-date=2014-02-28". Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Viehoff, Henrich (1853). Periode des eklestischen Universalismus 1806-1832. [Bd. 3] [Period of Eclectic Universalism 1806-1832. In series: Goethe's poems explained and traced back to their causes, sources and models, together with a collection of variants and gleanings]. In series: Goethe's Gedichte erläutert und auf ihre Veranlassungen, Quellen und Vorbilder zurückgeführt, nebst Variantensammlung und Nachlese (in German). Vol. 3. Includes selection of poems by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Düsseldorf: Bötticher'schen Verlags Buchhandlung. p. 172. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Goethe (1815). "Freisinn". Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Албогачиева М. "Многоликая Ингушетия". Groznycity.ru. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Vospominaniya Kavkazskogo Ofitsera" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Немного о истории Владикавказа – часть 2 – 6 Января 2011 – История геноцида Ингушского|Чеченского народа". Vainax.ru. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Akty sobrannye kavkazskoj arxeograficheskoj komissiej (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Johanna Nichols (February 1997). "The Ingush (with notes on the Chechen): Background information". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- P.G.Butkov (1869). Materials of the new history of the Caucasus years 1722–1803. St. Petersburg. p. 165.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - E.Bronevski (1823). New geographical and historical perspectives of the Caucasus. Vol. 2. Moscow. p. 159.

- U. Klaprot (1812). Travel in the Caucasus and Georgia 1807–1808. Berlin. p. 651.

- N.Grabovski (1876). Ingush nation (their life and traditions). Tiflis. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - K.Raisov (1897). New illustrated guide in the Crimea and the Caucasus. Odessa. p. 295.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - G.G. Moskvitch (1903). Illustrated practical guide in the Caucasus. Odessa. pp. 161–162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - N.M. Suetin (1928). Geodesy of the Vladikavkaz. Vladikavkaz. p. 12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - V.P. Khristianovich (1928). Mountainous Ingushetia. Rostov-on-Don. p. 65.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - E.I.Krupnov (1971). Middle age Ingushetia. Moscow. p. 166.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- P.G.Butkov (1869). Materials of the new history of the Caucasus years 1722–1803. St. Petersburg. p. 165.

- ^ "Caucasus and central Asia newsletter. Issue 4" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ^ "Chechnya: Chaos of Human Geography in the North Caucasus, 484 BC – 1957 AD". www.semp.us. November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010.

- ^ Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1925). Ocherki Russkoi Smuti. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ MINORITY RIGHTS GROUP INTERNATIONAL, THE NORTH CAUCASUS:Minorities at a Crossroads Archived 7 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zelkina, Anna (1993). "Islam and Politics in the North Caucasus". Religion, State and Society. 21 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1080/09637499308431583. Abstract Archived 31 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Revolution and Sovietization in the North Caucasus" Caucasian Review, 1955, No. 1, pp. 47–54. No. 3, pp.45–53

- ^ General Staff of the War Office (20 September 2018), Daily Review of the Foreign Press, vol. 27, London: H.M.S.O, p. 393, OCLC 988661052, [Digest], archived from the original on 7 April 2023, retrieved 28 February 2014. Searchable only. (No preview accessible.) Archived 12 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "1900.ethnia.org". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Ben Cahoon. "Russian Civil War Polities". Worldstatesmen.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Общественное движение ЧЕЧЕНСКИЙ КОМИТЕТ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО СПАСЕНИЯ". Savechechnya.com. 24 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Вассан-Гирей Джабагиев". Vainah.info. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Шкуро, А. Г. (2016). Гражданская война в России. Записки белого партизана (in Russian). Directmedia. p. 336. ISBN 978-5-4475-8722-2. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "Spetspereselentsi: history of mass repressions and deportations of Ingushes in 20th century". Ingushetiya news agency. March 2005. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007.

- ^ "The Ingush People". Linguistics.berkeley.edu. 28 November 1992. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Через 63 года в отношении защитников Малгобека восстановлена историческая справедливость". Российская газета. 27 November 2007. Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Explore Chechnya's Turbulent Past ~ 1944: Deportation | Wide Angle". PBS. 25 July 2002. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Arbatov, Alekseĭ; Antonia Handler Chayes (1997). Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union. MIT Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-262-51093-6.

The conditions were so horrendous that around 25 percent of the [Ingush] deportees perished on the journey

- ^ Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-521-63619-1.

A total of 144,704 (23.7 percent) of all deported Chechens, Ingush, Balkars (1944) and Karachai (1943) died in the period from 1944 through 1948

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (22 January 2001). Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-674-00313-2. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Prague Watchdog – Crisis in Chechnya – The deportation of 1944 – how it really was". Watchdog.cz. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "The 60th Anniversary of the 1944 Chechen and Ingush Deportation: History, Legacies, Current Crisis". Archived from the original on 20 January 2009.

- ^ "Chechen Journal Dosh". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "The Ingush (with notes on the Chechen): Background information". Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Ingushetia.ru news agency (January 2008). "35 years later. Ingush protest of 1973". www.ingushetiya.ru. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ О реабилитации репрессированных народов Archived 30 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Economist 1992. Ethnic cleansing comes to Russia. The Economist, 28 November 1992, p. 60.

- ^ N. Evloev (January 2008). "A message of Nazir Evloev Press Secretary of Ingushetia MVD (Police)". www.ingushetiya.ru. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ В Москве осетины похищают ингушей! (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2009.

- ^ "Ingush FSB Officer Shot Dead". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ За похищениями ингушей в Москве стоят высокопоставленные чиновники Северной Осетии (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Abduction Failed: Fifteen North Ossetia Law Enforcers Detained in Ingushetia". Memo.ru. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "АНО "МАШР" – Главная". Mashr.org. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ B.Polonkoev (August 2007). "The Murderers are not Insurgents". www.gazeta.ru. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ "The Russian republic rocked by car bomb". CNN. March 2008. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ "BBC NEWS – Europe – Q&: Conflict in Georgia". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ^ R.Khautiev (August 2008). "Silence in Ingushetia". www.ingushetiya.ru. Retrieved 17 August 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ BBC (31 August 2008). "Kremlin critic shot in Ingushetia". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ Blomfield, Adrian (1 September 2008). "Russia faces new Caucasus uprising in Ingushetia". Telegraph.co.uk. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Tension in Ingushetia after journalist's death". Financial Times. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Russians ambushed in Ingushetia". BBC News. 18 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Two Russian soldiers killed in attack in Ingushetia". Monsters and Critics. 18 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Отправлен в отставку президент Ингушетии Мурат Зязиков Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 31 October 2008 (in Russian)

- ^ Echo of Moscow, Указом президента России Дмитрия Медведева новым главой Ингушетии стал Юнус-Бек Евкуров Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 31 October 2008 (in Russian)

- ^ "The peaceful exception". The Economist. 9–15 April 2011.

- ^ Khasan Sampiev. "The Land of Towers". Archived from the original on 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Чечня FREE.RU – Новости Чечни, России и мира". Чечня FREE.RU. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- ^ TIMELINE OF VIOLENCE IN INGUSHETIA: SUMMER-FALL 2007 Archived 31 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ingushetia accuses Russian military desecrating monuments". Russian newsru.com. 15 July 2001. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "FSB building in Magas bombed". Pravda (English ed.). 15 September 2003. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Gheddo, Piero. "Magomed Yevloyev, critic of the Kremlin, killed by police". Asianews.it. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "77 Names Added to Slain Journalists Memorial in Washington D.C". Fox News. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Senior judge killed in Ingushetia". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Another Killing in Region Bordering Chechnya". The New York Times. 14 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Harding, Luke (22 June 2009). "Ingushetia president survives assassination attempt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Ingush minister shot dead at work". BBC. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Secretary Clinton Honors Two Champions of Human Rights Day » US Mission Geneva". Geneva.usmission.gov. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Ingushetia hit by suicide attack". BBC News. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Syria crisis: Border town shows conflict's patchwork forces". BBC News. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "В Сирии воюют ингуши, и возглавляют одни из самых дерзких боевых групп повстанцев - HABAR.ORG". habar.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Магомед Хазбиев: Если хотите меня остановить – убейте". Ingushetiyaru.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "На Украину выехали 4 инструктора боевиков с Северного Кавказа". LifeNews (in Russian). 2 February 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "В Ингушетии заговорили о выходе из РФ по крымскому сценарию". censor.net.ua. 20 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ "Российские официальные структуры сообщают об убийстве руководителя ингушских партизан – Артура Гетагажева" [Russian officials declare Getagazhev dead]. habar.org. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Ingush are fighting in Ukraine on both sides". 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Побочные эффекты". Эхо Кавказа. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Война в Ингушетии продолжается" [War in Ingushetia continues]. Эхо Кавказа. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Нападение боевиков на морг в Ингушетии сняла камера". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "В Ингушетии митинг против карикатур на пророка Мухаммеда собрал до 20 тысяч человек". newsru.com. 17 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ ЗАО ИД «Комсомольская правда» (17 January 2015). "Обращение главы Ингушетии к 20-тысячному антикарикатурному митингу: "Западная истерия вокруг ислама – это госэкстремизм"". ЗАО ИД «Комсомольская правда». Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Andrew Roth [@ARothWP] (28 February 2015). "Image of car purported to have carried Nemtsov's murderers has Ingush plates" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Медведев отправил в отставку президента Ингушетии". Old.lenta.ru. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "О ПРЕОБРАЗОВАНИИ ПОСЕЛКА ГОРОДСКОГО ТИПА СУНЖА СУНЖЕНСКОГО РАЙОНА РЕСПУБЛИКИ ИНГУШЕТИЯ, Закон Республики Ингушетия от 25 ноября 2016 года No.43-РЗ". docs.cntd.ru. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года. Том 1 [2020 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1] (XLS) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Federal State Statistics Service (21 May 2004). Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- ^ "Каталог публикаций::Федеральная служба государственной статистики". Gks.ru. 8 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "Демографический ежегодник России" [The Demographic Yearbook of Russia]. Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни при рождении" [Life expectancy at birth]. Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System of Russia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "ВПН-2010". perepis-2010.ru. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Caucasus Times poll". Caucasus Times. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia" Archived 6 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Sreda, 2012.

- ^ Stefano Allievi and Jørgen S. Nielsen (2003). Muslim networks and transnational communities in and across Europe. Vol. 1.

- ^ Johanna Nichols (February 1997). "The Ingush (with notes on the Chechen): Background information". University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Stephen Bowers; et al. (2004). "Islam in Ingushetia and Chechnya". Faculty Publications and Presentations of the Helms School of Government of Liberty University. 29. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Хмцсьяйхи Цнясдюпярбеммши Смхбепяхрер". Humanities.edu.ru. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (21 May 2004). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации" [Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Социально-экономические характеристики. Official website of Ingushetia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Die Hoechsten". Gipfel-und-grenzen.de. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "Ingushetia wants to attract Chinese tourists". TASS. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "UFC Rankings, Division Rankings, P4P rankings, UFC Champions | UFC.com". www.ufc.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Идрис Базоркин. "Идрис Базоркин". Livelib.ru. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ "2008 Beijing Olympics Results: Rakhim Chakhkiev Wins Gold". Transworldnews.com. 23 August 2008. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "ИССА КОДЗОЕВ – Учитель, Писатель, Патриот". rfi.fr. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Гарант-Интернет. "Обзор публикаций СМИ | Интернет-конференция Председателя Верховного Суда Российской Федерации Лебедева Вячеслава Михайловича | Гарант-Интернет". Garweb.ru. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Kaku, Michio (10 June 2012). "International Herald Tribune". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

Sources

[edit]Documents

[edit]- Конституционный закон №57-РЗ от 7 декабря 2010 г. «О государственном гимне Республики Ингушетия», в ред. Конституционного закона №2-РЗП от 4 июля 2011 г «О внесении изменений в некоторые законодательные акты Республики Ингушетия в связи с принятием Закона Республики Ингушетия от 11 октября 2010 года No. 3-РЗП "О поправке к Конституции"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Ингушетия", No.211–212, 18 декабря 2010 г. (Constitutional Law #57-RZ of 7 December 2010 On the State Anthem of the Republic of Ingushetia, as amended by the Constitutional Law #2-RZP of 4 July 2011 On Amending Various Legislative Acts of the Republic of Ingushetia Due to the Adoption of the Law of the Republic Ingushetia #3-RZP of 11 October 2010 "On the Amendment to the Constitution". Effective as of the day of the official publication.). (in Russian)

- 27 февраля 1994 г. «Конституция Республики Ингушетия», в ред. Закона №1-РЗП от 8 мая 2013 г. «О поправке к Конституции Республики Ингушетия». Опубликован: Сборник Конституций субъектов Федерации "Конституции Республик в составе Российской Федерации", выпуск 1, 1995. (February 27, 1994 Constitution of the Republic of Ingushetia, as amended by the Law #1-RZP of May 8, 2013 On the Amendment to the Constitution of the Republic of Ingushetia. ). (in Russian)

- Верховный Совет РСФСР. Закон от 4 июня 1992 г. «Об образовании Республики Ингушетия в составе РСФСР». (Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR. Law of 4 June 1992 On Establishing the Republic of Ingushetia Within the RSFSR. ). (in Russian)

Literature

[edit]- Albogachieva, Makka (2015). "Демаркация границ Ингушетии" [Demarcation of the borders of Ingushetia] (PDF). In Karpov, Yury (ed.). Горы и границы: Этнография посттрадиционных обществ [Mountains and Borders: An Ethnography of Post-Traditional Societies] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Kunstkamera. pp. 168–255. ISBN 978-5-88431-290-6.

- Gadzhiev, Magomed; Davudov, Omar; Shikhsaidov, Amri (1996). Gadzhiev, Magomed; Gamzatov, Gadzhi; Davudov, Omar; Osmanov, Ahmed; Osmanov, Magomed-Zagir; Shikhsaidov, Amri (eds.). История Дагестана с древнейших времен до конца XV в. [History of Dagestan from ancient times to the end of the 15th century] (PDF) (in Russian). Makhachkala: DSC of RAS. pp. 1–460.

- Gadzhiev, Magomed; Davudov, Omar; Kaymarazov, Gani; Osmanov, Ahmed; Ramazanov, Khidir; Shikhsaidov, Amri, eds. (2004). История Дагестана с древнейших времен до наших дней. Tom 1: История Дагестана с древнейших времен до XX века [History of Dagestan from ancient times to the present day. Vol. 1: History of Dagestan from ancient times to the 20th century] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 1–627. ISBN 5-02-009852-3.

- "ИНГУШЕ́ТИЯ" [INGUSHÉTIA]. Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- "Ingushetiya". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- Karpeev, Igor (2000). Dolmatov, Vladimir (ed.). "Наиб Ахбердилав" [Nail Akhberdilav]. Rodina (in Russian). No. 1/2. Moscow: FGBU Red. "Rossiyskaya Gazeta". pp. 90–93.

- Kodzoev, Nurdin (2002). "Глава 4. Ингушетия в XV—XVIII вв." [Chapter 5. Ingushetia in the 15–18th centuries]. История ингушского народа [History of the Ingush people] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kodzoev, Nurdin (2002). "Глава 5. Ингушетия в XIX в." [Chapter 5. Ingushetia in the 19th century]. История ингушского народа [History of the Ingush people] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Krupnov, Evgeny (1939). "К истории Ингушии" [To the history of Ingushiya]. Journal of Ancient History (in Russian). 2 (7). Moscow: Nauka: 77–90.

- Latham-Sprinkle, John (2022). "The Alan Capital *Magas: A Preliminary Identification of Its Location". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 85 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0041977X22000453. hdl:1854/LU-8681124. S2CID 249556131. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Martirosian, Georgi (1928). Нагорная Ингушия [Upland Ingushiya] (in Russian). Vladikavkaz: Izd-vo "Serdalo". pp. 1–153.

- Martirosian, Georgi (1933). История Ингушии [History of Ingushiya] (in Russian). Ordzhonikidze: Izd-vo "Serdalo".

- Nichols, Johanna (1997). The Ingush (with notes on the Chechen). University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006.

- Nichols, Johanna; Sprouse, Ronald L. (2004). Ghalghaai-Ingalsii, Ingalsii-Ghalghaai Lughat [Ingush-English and English-Ingush Dictionary] (in English and Ingush). London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 1–563. ISBN 9780415315951.

- Shnirelman, Victor (2006). Kalinin, Ilya (ed.). Быть Аланами: Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке [To be Alans: Intellectuals and Politics in the North Caucasus in the 20th Century] (in Russian). Moscow: NLR. pp. 1–691. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. ISSN 1813-6583.

- Tmenov, Vitaly; Kuznetsov, Vladimir; Gutnov, Felix; Totoev, Felix (1987). "Глава IX: Северная Осетия в XIV —XV вв." [Chapter 9: North Ossetia in the 14th-15th centuries]. In Dzugaeva, E. Kh.; et al. (eds.). История Северо-Осетинской АССР: С древнейших времен до наших дней [History of the North Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic: From ancient times to the present day] (in Russian). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Ordzhonikidze: Ir. pp. 133–150.

- Volkova, Nataliya (1973). Lavrov, Leonid (ed.). Этнонимы и племенные названия Северного Кавказа [Ethnonyms and tribal names of the North Caucasus] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 1–210.

External links

[edit]- News from Ingushetia

- News and History of Ingushetia

- Official website of Ingushetia (in Russian)

- Unofficial website of Ingushetia (in Russian)

- Ingush Music/Video/Literature website (in Russian)

- Magas, Ingush youth website (in Russian)

- Head of Ingushetia's website (in Russian)

- Ingushetia's Republic News Portal (in Russian)

- Ingushetia Videos (in Russian)

- National Project: People of Ingushetia Archived 9 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)