George's Day in Spring

| Saint George's Day Saint George's Day in Spring | |

|---|---|

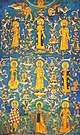

Icon of Saint George | |

| Date | 6 May |

| Next time | 6 May 2025 |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Saint George's Day, and George's Day in Autumn |

George's Day in Spring, or Saint George's Day (Serbian: Ђурђевдан, romanized: Đurđevdan, pronounced [ˈdʑûːrdʑeʋdaːn]; Bulgarian: Гергьовден, romanized: Gergyovden; Macedonian: Ѓурѓовден, romanized: Ǵurǵovden; Russian: Егорий Вешний, romanized: Yegoriy Veshniy, or Russian: Юрьев день весенний, romanized: Yuryev den vesenniy, lit. 'George's Day in Spring'), is a Slavic religious holiday, the feast of Saint George celebrated on 23 April by the Julian calendar (6 May by the Gregorian calendar). In Croatia and Slovenia, the Roman Catholic version of Saint George's Day, Jurjevo is celebrated on 23 April by the Gregorian calendar.

Saint George is one of the most important saints in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. He is the patron military saint in Slavic, Georgian, Circassian, Cossack and Chetnik military tradition. Christian synaxaria hold that Saint George was a martyr who died for his faith. On icons, he is usually depicted as a man riding a horse and killing a dragon.

Beyond Orthodox Christian tradition proper, Đurđevdan is also more generically a spring festival in the Balkans.

Balkan tradition

[edit]

Saint George's Day, known as Đurđevdan (Ђурђевдан) in Serbian, is a feast day celebrated on 6 May (O.S. 23 April) in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[1] As such, it is celebrated on that date by the Serb community in former Yugoslavia and in the Serb diaspora. It is also one of the many family slavas.[2] The day is celebrated and known as Gergyovden in Bulgaria and Gjurgovdjen in Macedonia.[3] Đurđevdan is also a major holiday for the Romani communities in former Yugoslavia, whether Orthodox or Muslim.[4] The various spellings used by the Romani (Ederlezi, Herdeljez, Erdelezi) for it are variants of the Turkish Hıdırellez.[5][6] It is also celebrated by the Slavic Muslim community of Gorani in Kosovo, and by members of the uncanonical Montenegrin Orthodox Church.

The holiday's rituals and festivities are related to the legend of St. George who is pictured as a brave young knight on a white horse slaying a dragon and saving a young maiden.[7] The holiday celebrates the return of springtime and is considered an important one. Celebrations are closely associated with pagan rituals and festivities associated with the awakening of nature and arrival of spring, dominant in the Balkans but also present in Europe. These rituals primarily consisted of sheep grazing, ritual slaughtering of a lamb, preparation of various dishes, ritual bath in the river or springs, setting of live fires, decorating with greenery and flowers and conducting of love spells.[8]

About a third of the population in Serbia have St. George as a patron saint, meaning that St. George's Day or Đurđevdan is celebrated as a krsna slava, through a family feast with ritual glorification. A popular tradition on St. George's eve is decorating home gates and houses with greens and flowers, this is particularly done by families whose patron saint is St. George.[2] A common way Đurđevdan is celebrated by Serbs is by "preparing a container of roses and green foliage, with an egg placed in the centre. Fresh water is poured over the flowers, and if the weather is kind enough, the container is placed in the garden. Children will be encouraged to wash their faces in this water and wishes for their good health are made by parents and grandparents."[9]

In Serbia, the celebration is linked to the end of Turkish rule, recollecting the days when fighters made plots and plans in woodland hideouts.[9] In the past, the date was used by the fighters for gathering and organizing their units for campaigns, leading to battles up until the end of November when they disbanded and returned to their villages to await the arrival of spring again, when trees turned new leaves.[10] Thus another custom is spending the day in nature. Other traditions in some parts of Serbia include the ritual sacrifice of lamb, bathing children in spring flowers and blossoms or nettles and herbs. The Prayer under Midžor Mt. Peak is a festival which has been organized since 2000 in the village of Vrtovac and includes prayer, national dances, local cuisine contests and other cultural events.[11] Serbs around the world also celebrate with singing, music, dancing and sporting events.[10]

The traditions of the Roma Durđevdan are based on decorating the home with flowers and blooming twigs as a welcoming to spring. It also includes taking baths added with flowers, washing hands with water from church wells and cracking painted eggs.[4] Also the walls of the home could be washed with the water. On the day of the feast it is most common to grill a lamb for the feast dinner. The inclusion of music is also important during the holiday; dancing and singing is common as are performances from traditional brass bands.[12]

In Bulgaria, May 6 is celebrated as St. George's Day as well as the Day of the Bulgarian Army with a military parade. St. George is considered the patron of spring verdure and fertility, and of shepherds and farmers.[13] Cattle rituals are performed, including the sacrificing of a lamb, offered to the saint. Villagers perform the traditional Bulgarian chain dance Horo, bathe in morning dew and "drink three sips of silent water from local springs as a cure" while a ritual meal is placed on a large table for the whole village.[14]

In Macedonia, the harvesting of herbs is an important symbolic act, done in St. George's day eve or early morning on the day. It is through this that various customs and songs are performed. At its core, the Macedonian tradition is in "the celebration of nature, the awakening of vegetation and life in general." Some of the herbs which are picked are believed to be magical. Similar to Bulgarian and Serbian customs, they are "aimed at ensuring progress and fertility of goods and fields, health, happiness and progress of people". Pilgrimages to holy sites devoted to St. George are also done in some villages.[15]

In Croatia, the feast day of Jurjevo is celebrated on 23 April by the Roman Catholic Croats mainly in the rural areas of Turopolje and Gornja Stubica.[16] In Croatian George is called Juraj while in Serbian he's called Đorđe (Ђорђе); in Bulgarian Georgi (Георги) and in Macedonian Ǵorǵija (Ѓорѓија). The use of bonfires is similar to Walpurgis Night. In Turopolje, Jurjevo involves a Slavic tradition where five most beautiful girls are picked to play as Dodola goddesses dressed in leaves and sing for the village every day till the end of the holiday.

In Bosnia, the major holidays of all religious groups were celebrated by all other religious groups as well, at least until religion-specific holidays became a marker of ethnic or nationalist self-assertion after the breakup of Yugoslavia. Roman Catholic Christmas, Orthodox Christmas, and the two Muslim Bajrams were widely recognized by people of all ethnic groups, as was Ðurđevdan even though it was properly an Orthodox holiday and therefore associated with Serbs. Muslims in Bosnia referred to the holiday as Jurjev and many celebrated it, while those who lived primarily in mixed Muslim and Orthodox villages did not.[17]

The holiday's widespread appeal, beyond the Orthodox Christian groups, in the Balkans, is evidenced in Meša Selimović's novel Death and the Dervish, where the pious Muslim protagonist views it as a dangerous pagan throwback, but where it is clearly celebrated by all ethnic groups in the unnamed city of its setting (widely considered to be Sarajevo).[citation needed]

"Ðurđevdan" is also the name of a popular song by band Bijelo dugme. The song is originally found on their studio album Ćiribiribela from 1988. It is a cover song (with different lyrics) for a popular traditional folk song of the Romani, "Ederlezi". Which was largely made famous by Goran Bregović.

Eastern Slavic tradition

[edit]

Yuri's Day of Spring (Russian: Юрьев день весенний, romanized: Yuryev den vesenniy or Егорий Вешний, romanized: Yegoriy Veshniy) is the Russian name for either of the two feasts of Saint George celebrated by the Russian Orthodox Church.

Along with various other Christian churches, the Russian Orthodox Church celebrates the feast of Saint George on April 23 (Julian calendar), which falls on May 6 of the Western Gregorian calendar. In addition to this, the Russian Church also celebrates the anniversary of the consecration of the Church of St George in Kiev by Yaroslav the Wise (1051) on November 26 (Julian calendar), which currently falls on December 9. One of the Russian forms of the name George being Yuri, the two feasts are popularly known as Vesenniy Yuriev Den (Russian: Весенний Юрьев день, romanized: Vesenniy Yuryev den, literally: "Yuri's Day in the Spring") and Osenniy Yuriev Den (Russian: Осенний Юрьев день, romanized: Osenniy Yuryev den, literally: "Yuri's Day in Autumn").

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Riches 2015, p. 51.

- ^ a b Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, p. 8.

- ^ Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, p. 7, 9.

- ^ a b Ghirda, Vadim (10 May 2018). "Bosnian Roma celebrate St. George's Day". Fox News. Associated Press.

- ^ Cartwright, Garth (2005). Princes Amongst Men: Journeys with Gypsy Musicians. Serpent's Tail. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-85242-877-8.

- ^ Riches 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Georgevich, Maric & Moravcevich 1977, p. 174.

- ^ Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Riches 2015, p. 79.

- ^ a b Georgevich, Maric & Moravcevich 1977, p. 66.

- ^ Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, p. 9.

- ^ "Romani all over the World celebrate Durdevdan Today". Sarajevo Times. 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Bulgaria Celebrates St. George's Day, Army Day". novinite.com. 6 May 2014.

- ^ Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Terzić & Bjeljac 2018, p. 10.

- ^ Bousfield, Jonathan (2003). Croatia. Rough Guides. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-84353-084-8.

- ^ Bringa, Tone (1995). Being Muslim the Bosnian Way: Identity and Community in a Central Bosnian Village. Princeton University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-69100-175-3.

Sources

[edit]- Riches, Samantha (2015). St George: A Saint for All. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-477-9.

- Georgevich, Dragoslav; Maric, Nikolaj; Moravcevich, Nicholas (1977). Serbian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland: Volume 1 (PDF). Cleveland State University.

- Terzić, Aleksandra; Bjeljac, Zelijko (2018). "Saint George's day in the Balkans - customs and rituals in Bulgaria, Serbia and Macedonia". Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic SASA. 68 (3): 383–397. doi:10.2298/IJGI180130003T. hdl:21.15107/rcub_gery_885.