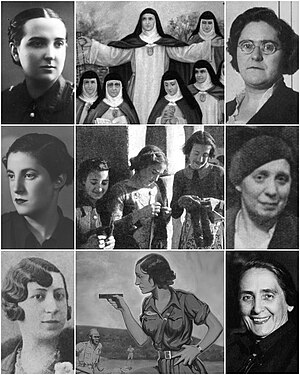

Women in the Second Spanish Republic

| Part of a series on |

| Women in the Spanish Civil War |

|---|

|

|

|

Women in the Second Republic period were formally allowed to enter the public sphere for the first time in Spanish cultural life, where they had a number of rights they had lacked before including the right to vote, divorce and access to higher education. The Second Spanish Republic had three elections, ones in 1931, 1933 and 1936. Women were able to run in all three and vote in the last two. Clara Campoamor Rodríguez, Victoria Kent Siano, and Margarita Nelken y Mansbergen were the most important women to emerge in this period.

Spanish feminism in this period was typically about "dual militancy", and was greatly influenced by anarchism. It was about trying to understand what role women should play in Spanish life. Women were also politically active in large numbers in this period as a result of constitutional reforms. While allowed in, they were still underrepresented in labor and anarchist organizations like UGT and CNT, and these organizations would often reinforce traditional gender roles. To succeed in their social and political efforts, women sometimes created their own organizations like Mujeres Libres though such organizations still were often not accepted by their male run counterparts. Some organizations were more willing to let women join, including Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM). This organization provided women with weapons training during the Second Republic to prepare for the war POUM saw as inevitable. Communist women also faced internal discrimination, which Dolores Ibárruri successfully navigated to join the top ranks of Partido Comunista de España.

Women on Spain's right were also socially and politically active, with Sección Femenina representing Falange, Acción Católica de la Mujer representing Catholic women, and Margaritas representing Carlists.

Pre-war interactions with the Guardia Civil and Falange starting in 1931 and occurring regularly until mid-1936, coupled with the Asturian miners' strike of 1934, would set the stage for the start of Spanish Civil War.

Background

[edit]One of the most important things about the Second Republic for women is it allowed them to formally enter the public sphere en masse.[1] The period also saw a number of rights available to women for the first time. This included the right to vote, divorce and access to higher education.[1]

Elections in the Second Republic

[edit]

The Spanish monarchy ended in 1931.[2] Following this and the end of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the Second Republic was formed. The Second Republic had three elections before being replaced by the Franco dictatorship.[2][3] These elections were held in 1931, 1933, and 1936.[3]

June 1931 elections

[edit]Following the failure of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, Spain set about writing a constitution. The initial draft did not give women the right to vote, though it did give them the right to run for office on 8 May 1931 for the June elections.[4][5] The first women to win seats in Spain's Cortes were Clara Campoamor Rodríguez, Victoria Kent Siano, and Margarita Nelken y Mansbergen following the June 1931 elections, when women still did not have the right to vote.[6][7][8][9]

1933 elections

[edit]

For the first time, for the 1933 elections, women could vote in the national elections.[10] CNT helped bring a right wing government to power after the 1933 elections by refusing to support the Popular Front alliance, and largely chose to abstain from the elections. They changed their positions for the 1936 elections, which assisted in bring the left back into power in the Second Republic.[11] The victory of conservative factions in the 1933 elections was blamed on women, and their voting practices in that election. They were viewed as being controlled by the Church.[3] The elections also saw conservative male leaders try to change the goals of the ACM. Rather than having the ACM try to accomplish political goals, they sought to direct participants to be more engaged in charity work and supporting working-class families.[12]

Campoamor, along with Kent, lost her seat in the Cortes following the 1933 elections.[3][10] The most active of the three women elected in 1931, she had been heckled in the congress during her two-year term for her support of divorce. She continued to serve in government though after being appointed the head of Public Welfare later that year, only to leave her post in 1934 in protest to the government response to the 1934 Revolution of Asturias.[3]

Nelken faced similar problems in the Cortes. Her mother was French, and her father was a German Jew. As a consequence, before she was allowed to sit in 1931, Nelken had to go through special bureaucratic procedures to insure she was a naturalized Spanish citizen. Her political interests were looked down upon by her male peers, including Prime Minister Manuel Azaña. Her feminist beliefs worried and threatened her male colleagues in the Cortes. Despite this, she was reelected in 1933, and found herself subject to constant attacks in the media as she proved a constant irritant to male party members who sometimes resorted to racist attacks in the Cortes to shut her down.[3] Still, she persevered, winning election 1931, 1933, and 1936. Disillusionment with the party led her to change membership to the Communist Party in 1937.[3]

Matilde de la Torre won election in 1933, representing Asturias in the Cortes.[3]

February 1936 elections

[edit]The Popular Front was a coalition of leftist parties created during the Second Spanish Republic ahead of the 1936 elections as a way of ensuring a left wing majority in the Congreso de Diputados.[13][14] The ability to do so was a result of a number of complex factors, but was assisted by the decision of the Communist Party of Spain to engage with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and not dismiss them as irrelevant supporters of the bourgeoisie.[15] Their goal was to win back government, after right-wing factions had won the elections in 1933.[3][16] A previous attempt at an alliance ahead of the 1933 elections had largely failed because of opposition by the CNT.[16]

The February 1936 elections saw the return of a leftist government, with Popular Front aligned parties able to form a government. They replaced a repressive right-leaning government that had been in power for the two previous years.[17][18] They ran on progressive platform, promising major reforms to government. In response, even as the left began reform plans to undo conservative efforts in the previous government, the military began planning how to overthrow the new government.[6][18][19] Popular Front, in contrast, refused to arm its own supporters out of fear they would then use them against the Government.[19]

During the elections, pamphlets were distributed in Seville that warned women that a leftist Republican victory would result in the government removing their children from their homes and the destruction of their families. Other pamphlets distributed by the right in the election warned that the left would turn businesses over to the common ownership of women.[20]

Ibárruri campaigned for a deputy in the Cortes ahead of the 1936 elections as a member of the Popular Front. During her campaign in Asturias, she campaigned before groups of socialists, communists, anti-fascists, and Republicans. She used her experiences to improve her oratory skills that would serve her later during the Civil War by observing other speakers who managed to successfully engage audiences.[21] Ibárruri won, and entered the Cortes as a member of the Popular Front, in the communist minority. Unlike some of their peers on the left, she and other communists advocated citizens taking up arms in preparation for what they saw as the coming conflict.[21]

Campoamor found herself locked out of the political process for the 1936 elections, as she had criticized her Radical Party for not supporting women's issues and removed herself from their list. Serving as President of Organización Pro-Infancia Obrera, she tried to find another political party that would allow her on their list while also advocating for women's rights. Failing to do so, she tried and failed to create her own political party.[10]

The 1936 elections saw Julia Álvarez Resano enter parliament as a member of PSOE. She came to the Cortes having previously served as a defense lawyer for the Spanish Federation of Land Workers.[3] Matilde de la Torre won election again in 1936.[3]

Feminism

[edit]Feminism in the Republican and Civil War eras was typically about "dual militancy," and was greatly influenced by anarchism, and understanding the role feminism should play in society.[7] The Civil War would serve as a break point for feminist activity inside Spain. There was little continuity in pre-war and post war Spanish feminism.[7][22]

This period was dominated by a contest of wills between Partido Republicano Radical Socialista (PRRS)-aligned Victoria Kent and Partido Republicano Radical-aligned Clara Campoamor. They fiercely contested the topic of women's suffrage. PSOE's Margarita Nelken supported Kent's position that women were not ready to vote.[23][12]

Female Republican Union

[edit]Campoamor, a centrist viewed by some of her colleagues in the Congreso de Diputados as right leaning, had created the Female Republican Union (Spanish: Unión Republicana de Mujeres) during the early part of the Second Republic.[23][24] Female Republican Union had the sole purpose of advocating for women's suffrage and did not support adding more rights beyond that.[23][12][6][7][8] It was often polemetic in its opposition to Kent's group Foundation for Women, and its opposition to women's suffrage.[24]

Foundation for Women

[edit]Victoria Kent and Margarita Nelken founded the Foundation for Women (Spanish: Asociación Nacional de Mujeres Española) in 1918.[24][23] Foundation for Women was a radical socialist organization at its inception, and aligned themselves with PSOE. The organization opposed women's suffrage, even as its founders sat in Spain's Cortes. The belief was if women were given the right to vote, most women would vote as their husbands and the Catholic Church told them to. This would fundamentally damage the secular nature of the Second Republic, by bringing in a democratically elected right wing government.[23][12]

Women's rights

[edit]

The founding of the Second Republic in 1931 brought in a five-year period that began to see both a change in historical gender roles and in legal rights for women. These changes were slowed in 1933, after a conservative block came into power. This group tried and succeed in rolling back many of the reforms passed in the previous two years.[6]

The Second Republic brought in legal and cultural changes for women in Spain, with most reforms occurring within the first two years of its founding on 14 April 1931.[6] The debate over women's suffrage began in the Cortes in 1931. This debate brought more attention to the legal status of women by Spanish Republicans. In turn, this led to many Republicans wanting to bring women into the public sphere, making women and their problems more visible, as a way to further advance the Republican political agenda.[3][8] Women eventually gained absolute equality under the law during the Second Republic.[7][8] Because of a deteriorating political situation and economic difficulties in the country, many of the rights attached to this were never fully realized or were later reversed.[6]

Other laws passed during the Second Republic included maternity leave, civil marriage, and no fault divorce.[25][23] Contraception was also legalized.[23] Despite divorce being made legal by the Second Republic, in practice it rarely occurred and only generally in large, liberal cities. The first year divorce was allowed in the Second Republic, only 8 of 1,000 marriages ended in divorces in Madrid.[23]

Many of the issues brought up by women were portrayed as the "women's question", which served to remove women's only policies from broader debates about societal needs. They removed them from context, and in turn served to reinforce societal views about gender.[4]

As a result of being locked out of or largely ignored by men leading political, anarchist and labor organizations, women created their own organizations during the Second Republic. One such organization was Mujeres Antifascists founded in 1933. It attracted support from many middle-class women, and sought to address issues like wage inequality, childcare provisions and employment opportunities in 1936. At the same time, they also wanted to increase the number of women serving on local councils.[6]

Legal equality for women was opposed by many on Spain's right. They saw it as a degeneration of Spain, which would result in the destruction of the Spanish family. This tension about the rights of women was part of their tension over the existence of the Republic, and one of the reason they were opposed to it.[26]

Women's suffrage

[edit]One of the first laws implemented allowed women to vote and to run for political office. This happened with Article 36 of the Constitution of the Second Republic, and came into force on 1 October 1931. The first women to win seats in Spain's Cortes were Clara Campoamor Rodríguez, Victoria Kent Siano and Margarita Nelken y Mansbergen.[6][7][8][12][19] They won these seats in June 1931, several months before women were given the right to vote. They were joined in February 1936 by Matilde de la Torre, Dolores Ibárruri and Federica Montseny. Nelken and Kent had both opposed giving women suffrage, arguing most women would vote for conservatives because of the influence of their husbands and the clergy, thus undermining the Spanish Republic.[6][7][26][12][19] Campoamor, in contrast, was a strong advocate of women's suffrage.[7][19]

Campoamor and Kent had both been waging highly public battles during the writing of the constitution of the Second Republic over the rights of women, and over the issue of universal suffrage. This battle would largely continue during the first term of Spain's Congreso de los Diputados.[23][6][7][8]

Campoamor, in arguing for women's suffrage before the Cortes on 1 October 1931, maintained that women were not being given the right to vote as a prize, but as a reward for fighting for the Republic. Women protested the war in Morocco. Women in Zaragoza protested the war in Cuba. Women went in larger numbers to protest the closure of the Ateneo de Madrid by the government of Primo de Rivera.[27] Campoamor also argued that women's inclusion was fundamental to saving the Republic by having a politically engaged populace, so that the errors of the French Republic would not be repeated.[27]

Kent, in contrast, received much more support from Spain's right, including Catholics and traditionalists, during this period of constitutional debate as she, alongside Nelken, opposed women's suffrage.[10] Kent and Campoamor became involved in a grand debate over the issue, receiving large amounts of press related to their arguments around women's suffrage.[10][19]

Universal suffrage was finally achieved in December 1931.[28] Legal equality for women was opposed by many on Spain's right. They saw it as a degeneration of Spain, which would result in the destruction of the Spanish family. This tension about the rights of women was part of their tension over the existence of the Republic, and one of the reason they were opposed to it.[26]

Education

[edit]The Second Republic had a goal of educating women. This was viewed as a radical concept, and many reactionaries inside the Republic were opposed to it. Many others supported it, seeing education as a tool to allow women to pass along Republican values to their children.[18]

The arts

[edit]Women were involved in art in this period.[3][29] Most of the prominent artists in the Second Republic came from the left.[3] Victorina Durán was an avant-garde costume maker, active during the early 1930s. She published about her thoughts on her art form in La Voz and La Libertad between 1935 and 1936.[29][30]

Employment and labor organizations

[edit]Margarita Balaguer attempted to collectivize seamstresses working with her at an haute couture fashion house during the Second Republic. Her efforts proved unsuccessful, largely as a result of her inability to connect with her co-workers as women in explaining the need to organize a union with them.[31]

Gibraltar was a major employer in southern Spain during the Second Republican, which upset the Spain's Ministry of State who felt they could not do much as the local economy benefited from the higher wages people earned there. While 4,000 men worked in the port, around 2,400 Spanish women made the daily voyage across the border to work in domestic roles in hotels, laundries, shops, cafes and homes of locals.[32]

Political activity

[edit]The changing political landscape of the Second Republic meant there was an environment for the first time in which women's political organizations could flourish.[23]

Women were also largely locked out of organized political groups and events in this period, even when said groups claimed to be for gender equity. Major trade unions at the time like UGT and CNT ignored specific needs of women, including maternity leave, childcare provisions and equal pay; they instead focused on general needs or needs of men in the workforces they represented.[6] The CNT also perpetuated gender inequality, by paying its female employees less than men in comparable positions.[33] Only 4% of UGT's membership was female by 1932.[6]

One of the biggest challenges faced by leftist women was Marxism prioritized the issue of class equality over gender issues. For anarchist, syndicalist, communist, and socialist women, this often resulted in male leadership prioritizing women's needs lower and locking women out of participation and governance as their needs did not directly relate to the class struggle.[12][19] Some leftist men, both in political and labor organizations, also resented women entering the workforce, viewing their lower wages as contributing to employers lowering wages among male workers.[19]

Despite differences in ideology, communist, Republican, and socialist women would come together for discussions about the political issues of the day. They also worked to mobilize women en masse to protest issues they felt were important. One such mobilization occurred in 1934, when the Republican government considered mobilizing its reserve forces military action in Morocco. Within hours of the news hitting the streets, communist, Republican, and socialist women had organized a women's march to protest the proposed action in Madrid. Many women were arrested, taken to the police headquarters and later released.[21]

Anarchists

[edit]On the whole, the anarchist movement's male leadership engaged in deliberate exclusion of women and discouragement from seeking leadership positions in these organizations.[6][7][34][2] Women were effectively locked out of the two largest anarchist organizations, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica.[2][19]

Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT)

[edit]Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) was one of the two major anarchist organizations active during the Second Republic. By July 1936, their membership ranks were over 850,000, and were organized by region and sector of employment.[2] CNT ignored specific needs of women, including maternity leave, childcare provisions and equal pay; they instead focused on general needs or needs of men in the workforces they represented.[6] The CNT also perpetuated gender inequality, by paying its female employees less than men in comparable positions.[33]

Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI)

[edit]Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) was one of the two major anarchist organizations in the Spanish Second Republic. It was created by more militant members of CNT.[2][19] Women found it difficult to join the organization, and even more difficult to get leadership positions.[2][19]

Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias (FIJL)

[edit]The Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth (Spanish: Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias, FIJL) was founded in 1932 as an anarchist youth organization. It was one the third most important anarchist organization of its day. Like CNT and FAI though, it largely rejected women's issues and discouraged women from becoming involved in its governance.[19] Like both FAI and CNT, it focused on the rights of Spain's working class.[19]

Mujeres Libres

[edit]Existing tensions within the anarchist movement, as a result of deliberate exclusion or discouragement by male leadership, eventually led to the creation of Mujeres Libres by Lucia Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada, and Amparo Poch y Gascón in May 1936, shortly before the start of the Civil War.[6][7][34][2][23][19] Suseso Portales served as the national vice-secretary.[34] Initially based in Madrid and Barcelona, the organization had the purpose of seeking emancipation for women.[6][7] Their goals also included "to combat the triple enslavement to which (women) have been subject: enslavement to ignorance, enslavement as women and enslavement as workers".[23] It was from the anarchist movement that many militia women (Spanish: milicianas) were to be drawn.[6]

Mujeres Libres organized ideological classes designed to raise the female consciousness. Compared to their fellow Second Wave feminists in the United States, they were more radical in that they provided job training skills, health information sessions, and classes where they taught other women how to read. This information was viewed as critical if they wanted women to be part of the wider revolutionary movement.[2][23][19] Lack of education was one of the reasons men had sidelined many other women in the movement, and Mujeres Libres sought to remove this sexist rational.[2][19] In their approach to women's liberation as requiring multiple solutions, they ended up being closer ideologically to intersectional feminism.[2] Mujeres Libres also set up storefront cultural centers (Spanish: ateneos libertario), which provided solutions on the local level, and decentralized governance in a way that made it accessible to everyone. They avoided direct political engagement through lobbying of the government.[2][23][19] They also did not identify as feminist, as they saw goals of other feminists at the time as too limited in their scope for the freedom they sought for their fellow women, perceiving feminism as too bourgeoisie.[19] It is only starting in the 1990s that they have been identified by academics as such.[19]

Anti-fascists

[edit]Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM)

[edit]One of Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista's (POUM) goals during the early part of the Second Republic was to give working-class women a feeling of empowerment. To do this, the Women's Secretariat set about organizing neighbor hood women's committees to address day-to-day concerns of women living in specific areas.[35]

POUM's Women's Secretariat also trained women in cities like Barcelona in using weapons. They wanted women to feel prepared for the war that seemed inevitable.[35] Known as the Women's Cultural Grouping in Barcelona, POUM's women's group also organized classes in Barcelona that saw hundreds of women taking part. Classes focused on hygiene, knitting, sewing, reading books, children's welfare and discussing a broad range of topics including socialist, women's rights, the origin of religious and social identities.[35] Contacts took place in this period between POUM's Alfredo Martínez and leadership in Mujeres Libres in Madrid about possibly forming an alliance. These talks never went anywhere.[35]

Communists

[edit]Partido Comunista de España (PCE)

[edit]During the Second Republic, Partido Comunista de España was the primary communist political organization in Spain.[36]

Communists began to recognize the importance of women during the Second Republic, and started to actively seek female members to broader their female based in 1932.[12] To this further this goal, the first communist women's organization, Committee of Women against War and Fascism in Spain, was created as a way of trying to attract women to communist-connected unions in 1933.[12] Membership for women in PCE's Asturias section in 1932 was 330, but it grew By 1937, it had increased to 1,800 women.[12]

During the Austrian miners action, the government of the Second Republic responded by arresting thousands of miners and closing down their workers centers. Women rose up to support striking and imprisoned miners by advocating for their release and taking jobs to support their families. PCE male leadership strove to find roles for women that better comported with what they saw as more acceptable for their gender and better fit into the new, more conservative legal framework being created by the Second Republic. This included changing the name of the Committee for Women against War and Fascism to Pro-Working Class Children Committee. PCE's goal and the actual result was to discourage women's active participation in labor protests.[12]

VII Comintern Congress in 1935 in Moscow had two representatives from the PCE. They were Ibárruri and Jose Díaz. Sesé and Arlandis attended as a representative of the Communist Party of Catalonia.[21] Ibárruri's profile rose so much during the Second Republic, while being coupled with the outlawing of the Communist Party, that she was regularly hunted by the Spanish police. This made it difficult for her to travel, both internally and externally.[21] Being too close to her would also prove deadly. Twenty-three year old Juanita Corzo, a member of Women Against War, would was given a death sentence in 1939 for aiding Ibárruri, which was later commuted to life in prison.[21]

Women in Partido Comunista de España faced sexism on a regular basis, which prevent them from rising up the ranks in leadership. They were denied the ability to be fully indoctrinated by keeping them out of communist ideological training classes. At the same time, men insisted women were not capable of leadership because they were not educated in these principals. The sexism these leftist women faced was similar to their counterparts on the right, who were locked out of activities of the Catholic Church for exactly the same reason.[36]

For the 1936 May Day celebrations, the Communist Party of Spain worked hard to convey a perception that they were one of the dominant political groups in the country by turning out party members in Madrid. They successfully organized hundred of communist and socialist women to participate in a march, where they chanted "Children yes, husbands no!" Spanish: ¡Hijos sí, maridos no!) with their fists clenched in the air behind huge Lenin and Stalin banners.[37] The party the year was also successful in convincing many socialist women to embrace Bolshevism.[37]

Matilde Landa became a PCE militant during the Second Republic while in Madrid. Following the start of the civil war, she worked at a PCE affiliated war hospital in Madrid. In 1939, she was tasked with reorganizing Madrid's Comité Provincial del Partido Comunista. Soon after, she was arrested by the Francoist government. Put into a prison in Sales, she was given a death sentence where she worked to overturn her and other women's death sentences by engaging in a writing campaign. By 1940, her death sentence was commuted and she was moved to a women's prison in Palma de Mallorca. This was one of the worst post-war women's prisons in Spain, where prison leaders also attempted coerced conversion to Catholicism. Rather than go through with a forced baptism in 1942, she committed suicide using a weapon. Landa did not immediately die, and lay in agony for over almost an hour before she died. During this time, prison officials baptized her.[38]

Spanish Committee of Women against War and Fascism

[edit]The Spanish Committee of Women against War and Fascism was founded as a women's organization affiliated with Partido Comunista de España in 1933.[12] They represented a middle class feminist movement.[21] As a result of PCE male governance trying to remove women from more active roles in the communist movement, its name was changed to Pro-Working Class Children Committee around 1934 following the Asturian miners strike.[12]

Dolores Ibárruri, Carmen Loyola, Encarnación Fuyola, Irene Falcón, Elisa Uriz, and María Martinez Sierra, part of a larger group representing Spain's communist, anarchist and socialist factions, attended the 1933 World Committee of Women against War and Fascism meeting in France.[21]

Falangists

[edit]Seccion Feminina

[edit]

Sección Femenina de la Falange Española was founded in 1934. It was led by Pilar Primo de Rivera, sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as a women's auxiliary organization of Falange.[25][18][39][23][40] Fascist in the mold of Mussolini's Italian party, both organizations were misogynistic in their approach to the goals of building a revolutionary organic society that would support traditional Spanish values. There were three things they saw as critical to doing this: the family, the municipality and the syndicate. Using traditional gender roles from the Catholic Church, they would impose their values on women in the home.[40] Given its goals of making women docile participants in civic life, the women's organization does not meet the definition of a feminist organization.[23] It was the only major Nationalist women's political organization, with a membership of 300 in 1934.[25][18][39][23] By 1939, Sección Femenina would eclipse the male run party in memberships, with over half a million women belonging to the group.[40]

Catholics

[edit]Women involved in Acción Católica de la Mujer (ACM) were involved in challenges to the Second Republic's laws that prohibited Catholic ceremonies and civic activities, including religious processions through towns. They often defied these laws, and were at the front of processionals in order to insure they were allowed to practice their more conservative version of Catholicism.[12] Mothers also continued to enroll their children in and support Catholic education in spite of government attempts to limit it.[12] Despite these political activities, male leadership in the Catholic Church and broader right leaning society attempted to get the ACM to be less political during the Second Republic. They encouraged ACM leadership to focus more on doing charity work, and on assisting working-class families.[12]

To this end, conservative leaders successfully oversaw the merger of ACM with the Unión de Damada del Sagrado Corazón in 1934. The new organization was called the Confederación de Mujeres Católics de Espana (CMCE). As a successful consequence, membership numbers dropped from 118,000 in 1928 to 61,354 members. It also saw the resignation of the more politically active women leaders from the newly formed CMCE. The newly merged organization also encouraged women explicitly to be less political, and participate in at most one or two demonstrations a year.[12]

Young conservative Catholic women defied their leaders, and sought to be politically active and visible in their goals. Sensing the political tides, these women started leaving ACM by 1932 and joined Juventud Católica Femenina in large numbers. From 9,000 members in 1928, the organization grew to 70,0000 by 1936, with the bulk of the increase happening between 1932 and 1935. These young Catholic women took the opportunity to gain public attention in ways that were not connected to their sexuality or charitable works. Many among them welcomed the potential enfranchisement the Second Republic was offering.[12]

Carlists

[edit]The Second Republic saw an increase in the number of traditionalist women's organizations, and in Carlist women's groups, as this group felt a need to defend their Catholic beliefs and traditions. Their numbers were helped by women such as Dolores de Gortázar calling women to defend their views and become involved in that process.[41] Carlists more broadly began using a mix of their traditional rallies and more modern political strategies to increase their political effectiveness and to avoid alienating people and minimize government scrutiny who feared another Carlist war.[41][42] The group transformed into a propaganda tool for the Communión Tradicionalista party. Members arranged musical evenings, organized religious acts and proselytized in people's homes.[43][41]

Some women in the Margaritas came from the women's section of Catholic Action.[44] For many Margaritas, it was important to defend their religion and traditions.[44] Their traditions revolved around creating an earthly version of the Holy Family. Fathers were in charge, and mothers were pious while their children were obedient.[26]

One of the key organizational aspects among Margaritas in this period was local, with Margaritas asking that territorial boundaries be respected when it came to their work but also discussing the need for new organizational structures to be discussed.[41] The largest group of Margaritas developed in Navarre, where they enjoyed political legitimacy that their male counterparts lacked. Women from the area included Dolores Baleztena, Carmen Villanueva, Clinia Cabañas, Josefa Alegría, Isabel Baleztena, Ascensión Cano, and Rosa Erice. Pilar Careaga was the most active and visible Margarita from Valencia and Rosa Urraca from the Basque Country.[41]

Republicans

[edit]Partido de Unión Republicana (PUR)

[edit]Despite many divisions on the left, communist and other women would often visit Republican Union Party (Spanish: Partido de Unión Republicana) (PUR) centers, where they would interact with other leftist women and discuss the political situation of the day during the early period of the Second Republic. Participants included Dolores Ibárruri, Victoria Kent, and Clara Campoamor. Many of these women were very knowledgeable about these topics, more so than many of their male peers.[21] This cross party collaborative discussion was at times threatening to male leaders in parties like the Republican Union Party, who in 1934 put a stop to it by posting police officers at the entrances to keep non-party members out. As a consequence, many women left the Republican Union Party at this time.[21]

Socialists

[edit]Prominent women socialists included Matilde Huici, Matilde Cantos, and Matilde de la Torre.[22] Women's caucus were often very weak inside the broader socialist party governance structure. As a consequence, they were often ineffective in advocating for women's rights.[22]

Partido Socialista Obrero Español

[edit]In general, PSOE began espousing a more militant approach to combating right wing actors inside Spain, continuing this thinking as the history of the Second Republic chugged along in the face of increasing numbers of labor conflicts and male leadership quarrels.[12]

Nelken was the political leader of the PSOE's women's wing. Her feminist beliefs worried and threatened her male colleagues in the Cortes. Despite this, Nelken was the only woman during the Second Republic to win three elections for the socialists to serve in the Cortes. Her election wins came in 1931, 1933, and 1936. Disillusionment with the party led her to change membership to the Communist Party in 1937.[3]

During the immediate pre-Civil War period, Campoamor tried to rejoin the Spanish socialists but was repeatedly rejected. Her support of universal suffrage, feminist goals, and divorce had made her an anathema to the male dominated party leadership. Eventually, in 1938, she went into exile in Argentina.[3] Martinez Sierra served for a time as a Socialist deputy in 1933.[21]

Prison reform

[edit]In 1931, Kent became the Director General of the Spanish prison system. She was the first woman to hold this post, and she largely disengaged from politics in order to enact reforms to the system.[3]

Kent changed prison guards in women's prisons from Catholic nuns to trained lay officials, who received instruction for their roles at the newly created Feminine Corps of Prison. She set about humanizing prisons, by trying to make them into correctional institutions. In some cases, this meant permitting prisoners to leave and return under specific circumstances.[3] She set up the Model Prison in Las Ventas, which was designed to hold around 500 prisoners.[45]

Pre-war interactions with the Guardia Civil and Falange

[edit]

Near the end of 1931, workers at a shoe factor in the village of Arnedo near Logroño were fired because they were members of Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT). Villagers decided to protest their firing outside the townhall, and were fired upon for no discernible reason by the Guardia Civil. Four women, a child and a male worker were killed, while another thirty were injured.[20]

Falangists were seeking to engage in attacks that would provoke Republican reprisals in 1935 and 1939. One such attack occurred on 9 March 1936 in Granada during a strike by workers. A squad of Falangist loyalist fired on workers, and their families who were protesting with them. Among the wounded were many women and children. The left in the city immediately retaliated by calling for a general strike, and people in the city setting fire to the offices of Falange, Acción Popular, the offices of the newspaper Ideal and two churches.[20]

October Revolution of 1934

[edit]

Women played roles behind the scenes in one of the first major conflicts of the Second Republic, when workers' militias seized control of the mines in Asturias.[36][12] Originally planned as a nationwide strike, the workers collective action only really took place in Asturias.[12] Some women were involved in propaganda and others in assisting the miners. After the government quelled the insurrection by bringing in Moroccan legionaries, some 30,000 people found themselves in prison and another 1,000 were put into graves. A large number of those put into prison were women. Women also played an advocacy role in trying to see their husbands and male relatives released.[36]

During the Austrian miners action, the government of the Second Republic responded by arresting thousands of miners and closing down their workers centers. Women rose up to support striking and imprisoned miners by advocating for their release and taking jobs to support their families. Following this, Partido Comunista de España tried to intentionally repress its female membership from becoming more politically active from within the party.[12] During fighting in Oviedo, women were on the battlefield serving in a variety of roles. At least one attended to the wounded while shelling went on around her. Others took up arms. Still more went from leftist position to leftist position with active shelling happening, providing fighters with food and motivational speeches.[12]

During the Asturian conflict, there were a few instances of women initiated violence. This fed into paranoia among those on the right that women would violently try to seize power from men. Both on the left and the right, these women were not viewed as heroic, and men wanted to limit their potential for further political action.[12] Women were also involved in building barricades, clothing repair, and street protests. For many women, this was the first time they were civically engaged without a male chaperone as in many cases, they were working on behalf of imprisoned male relatives.[46] Women were also killed in this conflict. Aida Lafuente was active on the front, and died during the Asturian conflict.[46]

There were a number of women playing important roles behind the scenes in organizing. They included Dolores Ibárruri, Isabel de Albacete, and Alicia García. They were aided by the PCE's Committee to Aid Workers' Children.[21]

More recently, academics have debated if the Asturian miners's strike represented the real start of the Spanish Civil War.[12] Imagery from the conflict was subsequently used by both sides for propaganda to further their own agenda, particularly inside PSOE who saw it the situation as a call for political unity on the left if they were to have any hope of countering the rise of fascism in Spain.[12] PSOE consequently used a lot of gendered imagery to sell people on their ideas.[12] Propaganda used featuring the events in October 1934 featured women in gender conforming ways that did not challenge their roles as feminine. This was done by male leadership with the intention of counteracting the image of strong women political leaders, who unnerved many on the right. Right wing propaganda at the time featured women as vicious killers, who defied gender norms to eliminate the idea of Spanish motherhood.[12]

Start of the Civil War

[edit]

On 17 July 1936, the Unión Militar Española launched a coup d'état in North Africa and Spain. They believed they would have an easy victory. They failed to predict the people's attachment to the Second Republic. With the Republic largely maintaining control over its Navy, Franco and others in the military successfully convinced Adolf Hitler to provide transport for Spanish troops from North Africa to the Iberian peninsula. These actions led to a divided Spain, and the protracted events of the Spanish Civil War.[6][18][47][2][48][12] It would not officially end until 1 April 1939.[48][12]

Franco's initial coalition included monarchists, conservative Republicans, Falange Española members, Carlist traditionalists, Roman Catholic clergy, and the Spanish Army.[17][6][49] They had support from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.[17][48] The Republican side included socialists, communists, and various other left-wing actors.[17][47][48]

The military revolt was announced on the radio across the country, and people took to the streets immediately as they tried to determine the extent of the situation, and if it was a military or political conflict. Ibárruri would soon coin the phrase "¡No pasarán!" a few days later, on 18 July 1936 in Madrid while on the radio from the Ministry of the Interior's radio station, saying, "It is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. ¡No pasarán!"[21]

At the start of the Civil War, there were two primary anarchist organizations: Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Representing working-class people, they set out to prevent the Nationalists from seizing control while also serving as reforming influences inside Spain.[2]

Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union signed the Non-Intervention Treaty in August 1936, promising not to provide material support for the war to any of the parties, even as Germany and Italy were already and continued to provide support to Spain's fascists.[19][21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b González Naranjo, Rocío (1 March 2017). "Usar y tirar: las mujeres republicanas en la propaganda de guerra". Los ojos de Hipatia (in European Spanish). Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hastings, Alex (18 March 2016). "Mujeres Libres: Lessons on Anarchism and Feminism from Spain's Free Women". Scholars Week. 1. Western Washington University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mangini, Shirley; González, Shirley Mangini (1995). Memories of Resistance: Women's Voices from the Spanish Civil War. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300058161.

- ^ a b Ripa, Yannick (2002). "Féminin/masculin : les enjeux du genre dans l'Espagne de la Seconde République au franquisme". Le Mouvement Social (in French). 1 (198). La Découverte: 111–127. doi:10.3917/lms.198.0111.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Lines, Lisa Margaret (2012). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739164921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bieder, Maryellen; Johnson, Roberta (2016-12-01). Spanish Women Writers and Spain's Civil War. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134777167.

- ^ a b c d e f Memory and Cultural History of the Spanish Civil War: Realms of Oblivion. BRILL. 2013-10-04. ISBN 9789004259966.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "CLARA CAMPOAMOR: Una mujer, un voto". Universidad de Valencia (in Spanish). Donna. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Bunk, Brian D. (2007-03-28). Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822339434.

- ^ Radcliff, Pamela Beth (2017-05-08). Modern Spain: 1808 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405186803.

- ^ Payne, Stanley. Spain's first democracy: the Second Republic, 1931-1936. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993. p. 267.

- ^ Rees, Tim; Thorpe, Andrew (1998). International Communism and the Communist International, 1919-43. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719055461.

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b c d Linhard, Tabea Alexa (2005). Fearless Women in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826264985.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Angela (2003-09-02). British Women and the Spanish Civil War. Routledge. ISBN 9781134471065.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t de Ayguavives, Mònica (2014). Mujeres Libres: Reclaiming their predecessors, their feminisms and the voice of women in the Spanish Civil War history (Masters Thesis). Budapest, Hungary: Central European University, Department of Gender Studies.

- ^ a b c Preston, Paul (1978-06-17). The Coming of the Spanish Civil War: Reform, Reaction and Revolution in the Second Republic 1931–1936. Springer. ISBN 9781349037568.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ibárruri, Dolores (1966). Autobiography of La Pasionaria. International Publishers Co. ISBN 9780717804689.

- ^ a b c Nash, Mary (1995). Defying male civilization: women in the Spanish Civil War. Arden Press. ISBN 9780912869155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ryan, Lorraine (January 2006). Pelan, Rebecca (ed.). A Case Apart: The Evolution of Spanish Feminism. Galway: National Women Studies Centre.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Montero Barrado, Jesús Mª (October 2009). "Mujeres Libres". El Catoblepaz (92 ed.). Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Cook, Bernard A. (2006). Women and War: A Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097708.

- ^ a b c d Keene, Judith (2007-04-10). Fighting For Franco: International Volunteers in Nationalist Spain During the Spanish Civil War. A&C Black. ISBN 9781852855932.

- ^ a b "Texto íntegro del discurso de Clara Campoamor en las Cortes". El País (in Spanish). 1 October 2015. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Congress. "Documentos Elecciones 12 de septiembre de 1927". Congreso de los Diputados. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b Javier., Huerta Calvo (2005). Teatro español (de la A a la Z). Peral Vega, Emilio, 1974-, Urzáiz Tortajada, Héctor. Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid): Espasa. ISBN 8467019697. OCLC 67840372.

- ^ Peláez Martín, Andrés (2003). Victorina Durán.

- ^ Fraser, Ronald (2012-06-30). Blood Of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War. Random House. ISBN 9781448138180.

- ^ Alberca, Julio Ponce (2014-11-20). Gibraltar and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39: Local, National and International Perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472525284.

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.

- ^ a b c Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. AK Press. ISBN 9781902593968.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Danny (2018-05-08). Revolution and the State: Anarchism in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Routledge. ISBN 9781351664738.

- ^ a b c d Cuevas, Tomasa (1998). Prison of Women: Testimonies of War and Resistance in Spain, 1939-1975. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791438572.

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley G. (2008-10-01). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300130782.

- ^ "10 de las mujeres más influyentes en la lucha feminista en España". El Rincon Legal (in Spanish). 8 March 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Esenwein, George R. (2005-11-16). The Spanish Civil War: A Modern Tragedy. Routledge. ISBN 9781134629688.

- ^ a b c Enders, Victoria L. (1992-12-01). "Nationalism and feminism: The Seccion Femenina of the Falange". History of European Ideas. 15 (4–6): 673–680. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(92)90077-P. ISSN 0191-6599.

- ^ a b c d e Roncal, Antonio Manuel Moral (2018-04-25). "Las carlistas en los años 30: ¿De ángeles del hogar a modernas amazonas?". Revista Universitaria de Historia Militar (in Spanish). 7 (13). ISSN 2254-6111.

- ^ Blinkhorn, Martin. Carlismo y contrarrevolución en España, 1931-1939, (1979) Barcelona, Crítica.

- ^ MacClancy, Jeremy (2000). The Decline of Carlism. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 9780874173444.

- ^ a b Lannon, Frances (2014-06-06). The Spanish Civil War: 1936–1939. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472810069.

- ^ Browne, Sebastian (2018-08-06). Medicine and Conflict: The Spanish Civil War and its Traumatic Legacy. Routledge. ISBN 9781351186490.

- ^ a b Seidman, Michael (2002-11-23). Republic of Egos: A Social History of the Spanish Civil War. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299178635.

- ^ a b Petrou, Michael (2008-03-01). Renegades: Canadians in the Spanish Civil War. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774858281.

- ^ a b c d Martin Moruno, Dolorès (2010). "Becoming visible and real: Images of Republican Women during the Spanish Civil War". Visual Culture & Gender. 5: 5–15.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 9781780224534.