Wildfires in the United States

Wildfires can happen in many places in the United States, especially during droughts, but are most common in the Western United States and Florida.[3] They may be triggered naturally, most commonly by lightning, or by human activity like unextinguished smoking materials, faulty electrical equipment, overheating automobiles, or arson.

Fire management policy favored aggressive wildfire suppression starting in the early 20th century.

In the 21st century, higher temperature and droughts driven by global warming have become more of a concern, and there has been increased advocacy for controlled burns and other measures to prevent fuel from accumulating in wild areas that can create more intense, larger, and difficult-to-control fires.

Firefighters are generally employed by governments, including municipal and county fire departments, regional mutual aid organizations, and state agencies like the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the New Jersey Forest Fire Service. Wildfire response is coordinated at the federal level by the National Interagency Fire Center, with the participation of the U.S. National Weather Service, and various agencies of the Departments of the Interior, Agriculture, Homeland Security, and Commerce. Fire squadrons of the United States Army are also sometimes called to large fires.

History of wildfire policy

[edit]

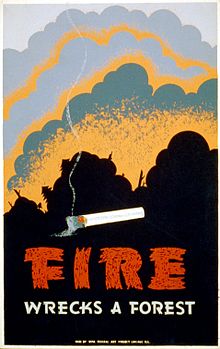

Since the turn of the 20th century, various federal and state agencies have been involved in wildland fire management in one form or another. In the early 20th century, for example, the federal government, through the U.S. Army and the U.S. Forest Service, solicited fire suppression as a primary goal of managing the nation's forests. At this time in history fire was viewed as a threat to timber, an economically important natural resource. As such, the decision was made to devote public funds to fire suppression and fire prevention efforts. For example, the Forest Fire Emergency Fund Act of 1908 permitted deficit spending in the case of emergency fire situations.[4] As a result, the U.S. Forest Service was able to acquire a deficit of over $1 million in 1910 due to emergency fire suppression efforts.[4] Following the same tone of timber resource protection, the U.S. Forest Service adopted the "10 AM Policy" in 1935.[4] Through this policy, the agency advocated the control of all fires by 10 o'clock of the morning following the discovery of a wildfire. Fire prevention was also heavily advocated through public education campaigns such as Smokey Bear. Through these and similar public education campaigns the general public was, in a sense, trained to perceive all wildfire as a threat to civilized society and natural resources. The negative sentiment towards wildland fire prevailed and helped to shape wildland fire management objectives throughout most of the 20th century.

Beginning in the 1970s public perception of wildland fire management began to shift.[4] Despite strong funding for fire suppression in the first half of the 20th century, massive wildfires continued to be prevalent across the landscape of North America. Ecologists were beginning to recognize the presence and ecological importance of natural, lightning-ignited wildfires across the United States. It was learned that suppression of fire in certain ecosystems may in fact increase the likelihood that a wildfire will occur and may increase the intensity of those wildfires. With the emergence of fire ecology as a science also came an effort to apply fire to ecosystems in a controlled manner; however, suppression is still the main tactic when a fire is set by a human or if it threatens life or property.[5] By the 1980s, in light of this new understanding, funding efforts began to support prescribed burning in order to prevent wildfire events.[4] In 2001, the United States implemented a National Fire Plan, increasing the budget for the reduction of hazardous fuels from $108 million in 2000 to $401 million.[5] In addition to using prescribed fire to reduce the chance of catastrophic wildfires, mechanical methods have recently been adopted as well. Mechanical methods include the use of chippers and other machinery to remove hazardous fuels and thereby reduce the risk of wildfire events.

Today the United States Forest Service maintains that "fire, as a critical natural process, will be integrated into land and resource management plans and activities on a landscape scale, and across agency boundaries. Response to wildfire is based on ecological, social and legal consequences of fire. The circumstance under which a fire occurs, and the likely consequences and public safety and welfare, natural and cultural resources, and values to be protected dictate the appropriate management response to fire" (United States Department of Agriculture Guidance for Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy, 13 February 2009). The five federal regulatory agencies managing forest fire response and planning for 676 million acres in the United States are the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the National Park Service, the United States Forest Service and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Several hundred million U.S. acres of wildfire management are also conducted by state, county, and local fire management organizations.[6] In 2014, legislators proposed The Wildfire Disaster Funding Act to provide $2.7 billion fund appropriated by congress for the USDA and Department of Interior to use in fire suppression. The bill is a reaction to United States Forest Service and Department of Interior costs of Western Wildfire suppression appending that amounted to $3.5 billion in 2013.[7]

Wildland-urban interface policy

[edit]An aspect of wildfire policy that is gaining more attention is the wildland-urban interface (WUI). More and more people are living in "red zones," or areas that are at high risk of wildfires. FEMA and the NFPA develop specific policies to guide homeowners and builders in how to build and maintain structures at the WUI and how protect against property losses. For example, NFPA-1141 is a standard for fire protection infrastructure for land development in wildland, rural and suburban areas[8] and NFPA-1144 is a standard for reducing structure ignition hazards from wildland fire.[9] For a full list of these policies and guidelines, see [2]. Compensation for losses in the WUI are typically negotiated on an incident-by-incident basis. This is generating discussion about the burden of responsibility for funding and fighting a fire in the WUI, in that, if a resident chooses to live in a known red zone, should he or she retain a higher level of responsibility for funding home protection against wildfires. One initiative aimed at helping U.S. WUI communities live more safely with fire is called fire-adapted communities.

Economics of fire management policy

[edit]

Today, in the United States, it is not uncommon for suppression operations for a single wildfire to cost millions of dollars.

Federal funding to manage wildfires comes from the Forest Service and the Department of the Interior. The combined annual appropriations from these two departments were around $1.6 billion from FY1994–FY2000. More recently, from FY2008–FY2017, the combined annual appropriations were about $4.0 billion. (During this period, the high was $5.2 billion in FY2008 and the low was $2.9 billion in FY2012.) Subsequent years were $3.6 billion (FY2013), $4.1 billion (FY2014), $3.6 billion (FY2015), and $5.0 billion (FY2016).[10]

Although fire suppression purports to benefit society,[by whom?] other options for fire management exist. While these options cannot completely replace fire suppression as a fire management tool, other options can play an important role in overall fire management and can therefore affect the costs of fire suppression.[11]

Short-term fire suppression can, in the long term, result in larger, more intense wildfire events. In economic terms, expenditures used for wildfire suppression in the early 20th century have contributed to increased suppression costs which are being realized today.[12]

Regional burden of wildfires

[edit]

Nationally, the burden of wildfires is disproportionally heavily distributed in the southern and western regions. The Geographic Area Coordinating Group (GACG)[13] divides the United States and Alaska into 11 geographic areas for the purpose of emergency incident management. One particular area of focus is wildland fires. A national assessment of wildfire risk in the United States based on GACG identified regions (with the slight modification of combining Southern and Northern California, and the West and East Basin); indicate that California (50.22% risk) and the Southern Area (15.53% risk) are the geographic areas with the highest wildfire risk.[14] The western areas of the nation are experiencing an expansion of human development into and beyond what is called the wildland-urban interface (WUI). When wildfires inevitably occur in these fire-prone areas, often communities are threatened due to their proximity to fire-prone forest.[15] The south is one of the fastest growing regions with 88 million acres classified as WUI. The south consistently has the highest number of wildfires per year. More than 50,000 communities are estimated to be at high to very high risk of wildfire damage. These statistics are greatly attributable to the South's year-round fire season.[16]

Effects of climate change

[edit]Climate change within the United States has increased heat and decreased moisture, which also increases the amount of dry fuel available, creating increasing fire frequency and risk.[17] [18] The increased risk may bring these fires closer or into urban areas.[19]

Along with the increased risk, studies show there will also be longer fire seasons and recovery time.[20] The longer fire seasons are due to the increased heat and length of summer and spring, which are the most common seasons for wildfires.[21] These longer seasons also start earlier due to the loss of snowpack during the winter causing less moisture in summer soil making it better fuel for wildfires.[22]

Western U.S. wildfire trends

[edit]

Save for areas near the Pacific coast, North America tends to be wetter in the East and drier in the West. The Western United States is a region of widespread, high-intensity wildfires. Aggressive suppression in the 20th century reduced wildfire size and intensity, but the resulting buildup of fuels has led to a resurgence in the last couple decades.[23]

Between 1970 and 2015, three times more "large fires" (fires that burn 1,000 acres or more) occurred in the Western U.S., with six times more acreage burnt, more than 1.7 million acres annually.[24] Between 1970 and 2003, the region experienced wildfire seasons that were 78 days longer.[25] It has been found that throughout the United States, 84% of wildfires are started by humans.[26]

A study conducted in 2019 found that from 1972 to 2018, California saw a fivefold increase in the area burned in any given year, and an eightfold increase in the area burned by summer fires.[22] Another study estimated that the area burned between 1984 and 2015 could have been half of what it was without human-caused climate change.[27] Finally, a 2020 research paper suggests that the number of autumn days with “extreme fire weather” has doubled over the past two decades.[28] The climate model analyses suggest that continued climate change will further amplify the number of days with extreme fire weather by the end of this century.[29]

In 2020, a series of particularly large wildfires burned across California, Oregon, and Washington. They were described as unprecedented, fueled by climate change and decades of bad environmental policies.[30][29]

United States agencies stationed at the National Interagency Fire Center in Idaho maintain a "National Large Incident Year-to-Date Report" on wildfires, delineating 10 sub-national areas, aggregating the regional and national totals of burn size, fire suppression cost, and razed structure count, among other data. In 2020, as of October 21, "Coordination Centers" of each geography report the following:[31]

Note: Check primary sources for up-to-date statistics.

| Coordination center | Acres | Hectares | Suppression costs | Structures destroyed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska Interagency | 171,045.7 | 69,219.7 | $14,837,241.00 | 8 |

| Northwest Area | 1,925,434.2 | 779,195.6 | $334,672,820.78 | 4,473 |

| Northern California Area | 3,961,089.6 | 1,602,996.1 | $1,369,875,556.25 | 7,410 |

| Southern California Area | 1,241,246.5 | 502,314.6 | $751,084,644.00 | 1,824 |

| Northern Rockies | 359,948.6 | 145,666.0 | $71,770,047.00 | 222 |

| Great Basin | 891,689.5 | 360,853.9 | $236,649,112.00 | 172 |

| Southwest Area | 1,036,287.6 | 419,370.7 | $192,069,000.96 | 63 |

| Rocky Mountain Area | 818,608.6 | 331,279.1 | $276,080,314.34 | 212 |

| Eastern Area | 10,508.4 | 4,252.6 | $522,398.58 | 19 |

| Southern Area | 2,678,366.3 | 1,083,896.4 | $14,692,891.11 | 313 |

| Totals[a] | 13,094,224.9 | 5,299,044.8 | $3,262,254,026.02 | 14,716 |

- ^ Year-to-date totals as of October 21, 2020

Notable wildfires

[edit]- List of Arizona wildfires

- List of California wildfires

- List of New Mexico wildfires

- List of Washington wildfires

- Peshtigo Fire, 1871; most loss of life in a US wildfire.

- Great Fire of 1910 in the US; shaped 20th-century wildfire policy

- 1988 Yellowstone wildfires

- 2011 Texas wildfires

- 2012 Oklahoma wildfires

- 2013 Beaver Creek Fire in Idaho.

- 2013 Yarnell Hill Fire

- 2016 Nevada wildfire[32]

- October 2017 Northern California wildfires

- 2018 Camp Fire

- 2018 Woolsey Fire

- 2020 Western United States wildfires

- December 2021 Kansas wildfires

- 2023 Hawaii wildfires

- Smokehouse Creek Fire

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Total Burn Acreage 1916-2010".Data Published by the United States Department of Agriculture ([1])

- ^ "Wildfire acres burned in the United States". OurWorldInData. 2021. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021. Data published by National Interagency Coordination Center; National Interagency Fire Center. (archive of NIFC data)

- ^ "Wildfire Hazard Potential". FireLab.org. United States Forest Service. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Pyne, S.J. 1984. Introduction to wildland fire: Fire management in the United States. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ a b Stephens, Scott L.; Ruth (2005). "Federal Forest Fire Policy in US" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 15 (2): 532–542. doi:10.1890/04-0545.

- ^ "National Interagency Fire Center". Nifc.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Graff, Trevor (23 August 2014). "Congressional wildfire bill would adjust state wildland fire funding". Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "NFPA 1141: Standard for Fire Protection Infrastructure for Land Development in Wildland, Rural, and Suburban Areas". Nfpa.org. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "NFPA 1144: Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire". Nfpa.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Hoover, Katie; Lindsay, Bruce (5 October 2017). "Wildfire Suppression Spending: Background, Issues, and Legislation in the 115th Congress" (PDF). Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Simon, Benjamin; Crowley, Christian; Franco, Fabiano (2022). "The Costs and Costs Avoided From Wildfire Fire Management—A Conceptual Framework for a Value of Information Analysis". Frontiers in Environmental Science. 10. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.804958.

- ^ Western Forestry Leadership Coalition (2010). "The true cost of wildfire in the western U.S." (PDF). Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "National Geographic Area Coordination Center Website Portal". Gacc.nifc.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Ager, A.A.; Calkin, P.E.; Finney, M.A.; Gilbertson-Day, J.W.; Thompson, M.P. (2011). "Integrated national-scale assessment of wildfire risk to human and ecological values". Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment. 25 (6): 1–20. doi:10.1007/s00477-011-0461-0. S2CID 55028640.

- ^ USDA Forest Service. 2011. Wildland fire and fuels fesearch and development strategic plan: Meeting the needs of the present, anticipating the needs of the Future. FS0854

- ^ Hoyle, Z. (2009). "The southern wildlife risk assessment: A powerful new tool for fighting fire in the south". Compass. 18: 12–14. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Westerling, A. L.; Bryant, B. P. (2008-03-01). "Climate change and wildfire in California". Climatic Change. 87 (1): 231–249. doi:10.1007/s10584-007-9363-z. ISSN 1573-1480. S2CID 17265646.

- ^ Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Harvey, Brian J. (2020-01-27). "Changing wildfire, changing forests: the effects of climate change on fire regimes and vegetation in the Pacific Northwest, USA". Fire Ecology. 16 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s42408-019-0062-8. ISSN 1933-9747.

- ^ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Warziniack, Travis (August 2021). "Effects of Climate Change on Natural-Caused Fire Activity in Western U.S. National Forests". Atmosphere. 12 (8): 981. doi:10.3390/atmos12080981. ISSN 2073-4433.

- ^ Harvey, Brian J. (2016-10-18). "Human-caused climate change is now a key driver of forest fire activity in the western United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (42): 11649–11650. doi:10.1073/pnas.1612926113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5081606. PMID 27791047.

- ^ An, Hyunjin; Gan, Jianbang; Cho, Sung Ju (September 2015). "Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Wildfire Risk in the United States". Forests. 6 (9): 3197–3211. doi:10.3390/f6093197. hdl:1969.1/183802. ISSN 1999-4907.

- ^ a b Williams, A. Park; Abatzoglou, John T.; Gershunov, Alexander; Guzman-Morales, Janin; Bishop, Daniel A.; Balch, Jennifer K.; Lettenmaier, Dennis P. (2019). "Observed Impacts of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Wildfire in California". Earth's Future. 7 (8): 892–910. Bibcode:2019EaFut...7..892W. doi:10.1029/2019EF001210.

- ^ Healy, Megan (March 12, 2019). "Cal Poly researchers ready to tackle California's catastrophic fires with new institute". KSBY. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Kenward, Alyson; Sanford, Todd; Bronzan, James (June 2016). "Western Wildfires A Fiery Future" (PDF). Assess.climatecentral.org. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Westerling, A.L.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Cayan, D.R.; Swetnam, T.W. (2006). "Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity". Science. 313 (5789): 940–943. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..940W. doi:10.1126/science.1128834. PMID 16825536.

- ^ Balch, J.K. (2017). "Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (11): 2946–2951. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.2946B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1617394114. PMC 5358354. PMID 28242690.

- ^ Abatzoglou, John T.; Williams, A. Park (2016). "Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (42): 11770–11775. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11311770A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607171113. PMC 5081637. PMID 27791053.

- ^ Goss, Michael; Swain, Daniel L.; Abatzoglou, John T.; Sarhadi, Ali; Kolden, Crystal A.; Williams, A Park; Diffenbaugh, Noah S. (2020). "Climate change is increasing the likelihood of extreme autumn wildfire conditions across California". Environmental Research Letters. 15 (9): 094016. Bibcode:2020ERL....15i4016G. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab83a7.

- ^ a b Singh, Maanvi (September 12, 2020). "'Unprecedented': the US west's wildfire catastrophe explained". The Guardian. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Leonard, Diana; Freedman, Andrew (September 11, 2009). "Western wildfires: An 'unprecedented,' climate change-fueled event, experts say". Washington Post. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ 2020 National Large Incident Year-to-Date Report (PDF) (Report). National Interagency Fire Center. October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Wildfires burn in 7 Western states, prompt evacuations". Associated Press. August 2, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Current map of fine particulates, including smoke, and hotspots (fires, flare stacks, among others).