West Auckland, New Zealand

West Auckland | |

|---|---|

Metropolitan West Auckland captured by a Planet Labs satellite in 2016 | |

| Coordinates: 36°48′S 174°36′E / 36.8°S 174.6°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Island | North Island |

| Region | Auckland Region |

| Government | |

| • MPs | Cameron Brewer (National) Carlos Cheung (National) Paulo Garcia (National) Carmel Sepuloni (Labour) Phil Twyford (Labour) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| Area code | 09 |

West Auckland (Māori: Te Uru o Tāmaki Makaurau or Māori: Tāmaki ki te Hauauru[1]) is one of the major geographical areas of Auckland, the largest city in New Zealand. Much of the area is dominated by the Waitākere Ranges, the eastern slopes of the Miocene era Waitākere volcano which was upraised from the ocean floor, and now one of the largest regional parks in New Zealand. The metropolitan area of West Auckland developed between the Waitākere Ranges to the west and the upper reaches of the Waitematā Harbour to the east. It covers areas such as Glen Eden, Henderson, Massey and New Lynn.

West Auckland is within the rohe of Te Kawerau ā Maki, whose traditional names for the area were Hikurangi, Waitākere, and Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa, the latter of which refers to the forest of the greater Waitākere Ranges area. Most settlements and pā were centred around the west coast beaches and the Waitākere River valley. Two of the major waka portages are found in the area: the Te Tōanga Waka (the Whau River portage), and Te Tōangaroa (the Kumeū portage), connecting the Waitematā, Manukau and Kaipara harbours.

European settlement of the region began in the 1840s, centred around the kauri logging trade. Later industries developed around kauri gum digging, orchards, vineyards and the clay brickworks of the estuaries of the Waitematā Harbour, most notably at New Lynn on the Whau River. Originally isolated from the developing city of Auckland on the Auckland isthmus, West Auckland began to expand after being connected to the North Auckland railway line in 1880 and the Northwestern Motorway in the 1950s.

Definition and etymologies

[edit]

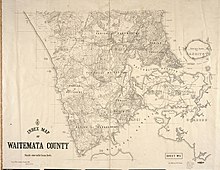

West Auckland is not a strictly defined area. It includes the former Waitakere City, which existed between 1989 and 2010 between the Whau River and Hobsonville,[2][3] an area which includes major suburbs such as Henderson, Te Atatū, Glen Eden, Titirangi and New Lynn. West Auckland typically also includes Avondale,[4] and Blockhouse Bay.[5][6] The Whau River and Te Tōanga Waka (the Whau portage) marked the border between the former Waitakere and Auckland cities, a border which was first established between Eden County on the Auckland isthmus and Waitemata County in 1876.[7] This border originally existed much earlier than, as the rohe marker between Te Kawerau ā Maki and Tāmaki isthmus iwi.[8] Avondale and Blockhouse Bay are east of the Whau River on the Auckland isthmus, but are included in the definition due to their strong historical ties.[9] Towns in southwestern Rodney, such as Helensville, Riverhead, Waimauku, Kumeū and Huapai are also often described as West Auckland.[10][11][12] Occasionally a stricter definition of West Auckland is used in reports and scientific literature, which includes just the Henderson-Massey, Waitākere Ranges and Whau local board areas.[13][14][15]

The traditional Tāmaki Māori names for the area include Hikurangi, Waitākere, Whakatū and Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa. Hikurangi referred to the central and western Waitākere Ranges south of the Waitākere River,[16] and was originally a name given by Rakatāura, the tohunga of the Tainui migratory canoe to a location south of Piha. Hikurangi is a common placename across Polynesia, and likely marked the point on the coast where the last light of the day reached.[17][16] The name Wai-tākere ("cascading water") originated as a name for a rock at Te Henga / Bethells Beach found at the former mouth of the Waitākere River,[18][19] which was later applied to the river, Ranges, and West Auckland in general.[16] The name refers to the action of the water striking the rock as the waves came into shore, and became popularised in the early 18th century during Te Raupatu Tihore ("The Stripping Conquest"), when a Te Kawerau ā Maki chief's body was laid on this rock.[20]

Whakatū is the traditional name for the Tasman Sea and the beaches south of Te Henga / Bethells Beach. It is a shortening of the name Nga Tai Whakatū a Kupe ("The Upraised Seas of Kupe"), referring to Kupe's visit to the west coast and his attempts to evade people pursuing him, by chanting a karakia to make the west coast seas rough.[21][22] Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa, the Great Forest of Tiriwa, references the name of Tiriwa, a chief of the supernatural Tūrehu people.[23] The name refers to all of the forested areas of the Waitākere Ranges south from Muriwai and the Kaipara Harbour portage to the Manukau Harbour.[16]

The modern use of West Auckland to refer to areas such as New Lynn and Henderson was popularised in the 1960s and 1970s.[24][25][26] Prior to this, West Auckland or Western Auckland mostly referred to the western portions of the old Auckland City, such as Ponsonby and Kingsland.[27][28][29][30] The name Auckland was originally given to the township of Auckland (now Auckland city centre) in 1840 by William Hobson, after patron George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland.[31]

Westies

[edit]Westie is a term used to describe a sub-culture from West Auckland, acting also as a societal identifier.[32] Similar to the word bogan, the stereotype usually involves a macho, working class Pākehā with poor taste, and the mullet haircut.[2] The Westie sub-culture was depicted in the New Zealand television series Outrageous Fortune (2005–2010), with particular attention to the distinctive fashion, musical preferences and interest in cars typical of this social group.[33][34]

Geography

[edit]Twenty-two million years ago, due to subduction of the Pacific Plate, most of the Auckland Region was lowered 2,000–3,000 metres (6,600–9,800 ft) below sea level, forming a sedimentary basin.[35] Approximately 20 million years ago, this subduction led to the formation of the Waitākere volcano, a partially submerged volcano located to the west of the modern Auckland Region.[36] The volcano is the largest stratovolcano in the geologic history of New Zealand, over 50 kilometres (31 mi) in diameter and reaching an estimated height of 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) above the sea floor.[37] Between 3 and 5 million years ago, tectonic forces uplifted the Waitākere Ranges and central Auckland, while subsiding the Manukau and inner Waitematā harbours.[38] The Waitākere Ranges are the remnants of the eastern slopes of the Waitākere volcano, while the lowlands of suburban West Auckland are formed of Waitemata Group sandstone from the ancient sedimentary basin.[35] Many of the areas directly adjacent to the Waitematā Harbour, such as New Lynn, Te Atatū and Hobsonville, are formed from rhyolitic clays and peat, formed from eroding soil and interactions with the harbour.[35]

The modern topography of West Auckland began to form approximately 8,000 years ago when the sea level rose at the end of the Last Glacial maximum.[39] Prior to this, the Manukau and Waitematā harbours were forested river valleys,[39] and the Tasman Sea shoreline was over 20 kilometres (12 mi) west of its current location.[40] The mouths of the rivers of West Auckland flooded, forming into large estuaries. Tidal mudflats formed at the Manukau Harbour river mouths, such as Huia, Big Muddy Creek and Little Muddy Creek.[39] Sand dunes formed along the estuaries of the west coast, creating beaches such as Piha and Te Henga / Bethells Beach.[39] The black ironsand of these beaches is volcanic material from Mount Taranaki (including the Pouakai Range and Sugar Loaf Islands volcanoes) which has drifted northwards, and potentially material from the Taupō Volcano and other central North Island volcanoes which travelled down the Waikato River as sediment.[35]

Ecology

[edit]

While much of West Auckland, especially the Waitākere Ranges, was historically dominated by kauri, northern rātā, rimu most of the kauri trees were felled as a part of the kauri logging industry.[41][42] One plant species is native to West Auckland, Veronica bishopiana, the Waitākere rock koromiko. A number of other plant species are primarily found in coastal West Auckland, including Sophora fulvida, the west coast kōwhai and Veronica obtusata, the coastal hebe.[43][44] Sophora fulvida is a common sight in West Auckland; other species of kōwhai are not allowed to be planted west of Scenic Drive.[45] The Waitākere Ranges are known for the wide variety of fern species (over 110),[45] as well as native orchids, many of which self-established from seeds carried by winds from the east coast of Australia.[46]

The areas of West Auckland close to the Waitematā Harbour, such as Henderson, Te Atatū Peninsula and Whenuapai, were formerly covered in broadleaf forest, predominantly kahikatea, pukatea trees, and a thick growth of nīkau palms.[45] As the soils around Titirangi and Laingholm are more sedimentary than the Waitākere Ranges volcanic soil, tōtara was widespread, alongside kohekohe, pūriri, karaka and nīkau palm trees.[45]

The Waitākere Ranges are home to many native species of bird, the New Zealand long-tailed bat and Hochstetter's frog, which have been impacted by introduced predatory species including rodents, stoats, weasels, possums and cats.[47] In 2002, Ark in the Park was established as an open sanctuary to reintroduce native species to the Waitākere Ranges.[48] Whiteheads (pōpokatea), North Island robin (toutouwai) and kokako have all been successfully re-established in the area,[49] and between 2014 and 2016 brown teals (pāteke) were reintroduced to the nearby Matuku Reserve.[47] The west coast beaches are nesting locations for many seabird species, including the banded dotterel and the grey-faced petrel,[47] and the korowai gecko is endemic to the west coast near Muriwai.[50]

The catchments of the Te Wai-o-Pareira / Henderson Creek and the Whau River are home to marine species including the New Zealand longfin eel, banded kōkopu, common galaxias (īnanga) and the freshwater crab Amarinus lacustris.[51][52][53]

Human context

[edit]Māori history

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The area was settled early in Māori history, by people arriving on Māori migration canoes such as the Moekākara and Tainui.[54] Māori settlement of the Auckland Region began at least 800 years ago, in the 13th century or earlier.[55] Some of the first tribal identities that developed for Tāmaki Māori who settled in West Auckland include Tini o Maruiwi, Ngā Oho and Ngā Iwi.[54]

One of the earliest individuals associated with the area is Tiriwa, a chief of the supernatural Tūrehu people, who is involved with the traditional story of the creation of Rangitoto Island, by uplifting it from Karekare on the west coast.[56][57] The early Polynesian navigator Kupe visited the west coast. The Tasman Sea alongside the coast was named after Kupe,[21] and traditional stories tell of his visit to Paratutae Island, leaving paddle marks in the cliffs of the island to commemorate his visit.[19] The Tainui tohunga Rakataura (also known as Hape) was known to have visited the region after arriving in New Zealand, naming many locations along the west coast.[16] He is the namesake of the Karangahape Peninsula at Cornwallis, as well as the ancient walking track linking the peninsula to the central Tāmaki isthmus (part of which became Karangahape Road).[58][59]

Early settlement

[edit]Most Māori settlements in West Auckland centred around the west coast beaches and the Waitākere River valley, especially at Te Henga / Bethells Beach.[60][61] Instead of living in permanent settlements, Te Kawerau ā Maki and other earlier Tāmaki Māori groups seasonally migrated across the region.[62] The west coast was well known for its abundant seafood and productive soil, where crops such as kūmara, taro, hue (calabash/bottle gourd) and aruhe could be grown, and for the diversity of birds, eels, crayfish and berries found in the ranges.[63] Archaeological investigations of middens show evidence of regional trade between different early Māori peoples, including pipi, cockles and mud-snail shells not native to the area.[61] Unlike most defensive pā found on the Auckland isthmus, not many Waitākere pā used defensive ditchwork, instead preferring natural barriers.[64]

Few settlements were found in the central Waitākere Ranges or in the modern urban centres of West Auckland.[61] Some notable exceptions were near the portages where waka could be hauled between the three harbours of West Auckland: Te Tōangaroa, the portage linking the Kaipara Harbour in the north to the Waitematā Harbour via the Kaipara River and Kumeū River; and Te Tōanga Waka, the Whau River portage linking the Waitematā Harbour to the Manukau Harbour in the south.[61][19] Defensive pā and kāinga (villages) were found close to the portages and the major walking tracks across the area, including at the Opanuku Stream and the Huruhuru Creek.[61][65] A number of settlements also existed on the Te Atatū Peninsula, including Ōrukuwai and Ōrangihina.[19][65]

Te Kawerau ā Maki

[edit]In the early 1600s, members of Ngāti Awa from the Kawhia Harbour, most notably the rangatira Maki and his brother Matāhu, migrated north to the Tāmaki Makaurau region, where they had ancestral ties.[66] Maki conquered and united Tāmaki Māori people of the west coast and northern Auckland Region. Within a few generations, the name Te Kawerau ā Maki developed to refer to this collective. Those living on the west coast retained the name Te Kawerau ā Maki, while those living at Mahurangi (modern-day Warkworth) adopted the name Ngāti Manuhiri, and Ngāti Kahu for the people who settled on the North Shore.[67]

In the early 1700s, Ngāti Whātua migrated south into the Kaipara area (modern-day Helensville). Initially relations between the iwi were friendly, and many important marriages were made between the peoples (some of which formed the Ngāti Whātua hapū Ngāti Rongo). Hostilities broke out and Ngāti Whātua asked for assistance from Kāwharu, a famed Tainui warrior from Kawhia. Kāwharu's repeated attacks of the Waitākere Ranges settlements became known as Te Raupatu Tīhore, or the stripping conquest.[68][69] Lasting peace between Te Kawerau ā Maki and Ngāti Whātua was forged by Maki's grandson Te Au o Te Whenua, who fixed the rohe (border) between Muriwai Beach and Rangitōpuni (Riverhead).[70]

In the 1740s, war broke out between Ngāti Whātua and Waiohua, the confederation of Tāmaki Māori tribes centred to the east, on the Tāmaki isthmus.[71] While Te Kawerau ā Maki remained neutral, the battle of Te-Rangi-hinganga-tahi, in which the Waiohua paramount chief Kiwi Tāmaki was killed, was held at Paruroa (Big Muddy Creek) on Te Kawerau ā Maki lands.[72][73]

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Te Kawerau ā Maki were only rarely directly contacted by Europeans, instead primarily receiving European products such as potatoes and pigs through neighbouring Tāmaki Māori tribes.[74] Significant numbers of Te Kawerau ā Maki lost their lives due to influenza and the Musket Wars of the 1820s.[74] After a period of exile from the region, Te Kawerau ā Maki returned to their lands, primarily settling at a musket pā at Te Henga / Bethells Beach.[75]

European history

[edit]The Cornwallis settlement and the establishment of Auckland

[edit]

The earliest permanent European settlement in the Auckland Region was the Cornwallis, which was settled in 1835 by Australian timber merchant Thomas Mitchell. Helped by William White of the English Wesleyan Mission, Mitchell negotiated with the chief Āpihai Te Kawau of Ngāti Whātua for the purchase of 40,000 acres (16,000 ha) of land in West Auckland on the shores of the Manukau Harbour.[76] After establishing a timber mill in 1836, Mitchell drowned only months later, and the land was sold to Captain William Cornwallis Symonds.[76] Symonds formed a company to create a large-scale settlement at Cornwallis focused on logging, trading and shipping, subdividing 220 plots of land in the area.[77][76] Cornwallis was advertised as idyllic and fertile to Scottish settlers, and after 88 plots of land had been sold, the settler ship Brilliant left Glasgow in 1840.[76] The settlement had collapsed by 1843, due to its remoteness, land rights issues and the death of Symonds,[76] with many residents moving to Onehunga.[78]

In 1840 after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, paramount chief Āpihai Te Kawau made a tuku (strategic gift) of land on the Waitematā Harbour to William Hobson, the first Governor of New Zealand, as a location for the capital of the colony of New Zealand. This location became the modern city of Auckland.[79] Many further tuku and land purchases were made; the earliest in West Auckland were organised by Ngāti Whātua, without the knowledge or consent of the senior rangatira of Te Kawerau ā Maki, however some purchases in the 1850s involved the iwi.[65]

Early settlements

[edit]

In 1844, 18,000 acres (7,300 ha) of land at Te Atatū and Henderson were sold to Thomas Henderson and John Macfarlane,[65] who established a kauri logging sawmill on Te Wai-o-Pareira / Henderson Creek.[80] Communities developed around the kauri logging business at Riverhead and Helensville, which were later important trade centres for the kauri gum industry that developed in the Waitākere Ranges foothills.[2][81] Between 1840 and 1940, 23 timber mills worked the Waitākere Ranges, felling about 120,000 trees. By the 1920s there was little kauri forest left in the Waitākeres,[2] and the area continued to be used to search for kauri gum until the early 20th century.[81]

The first brick kiln in West Auckland was built by Daniel Pollen in 1852, on the Rosebank Peninsula along the shores of the Whau River.[2][82] Brickworks and the pottery industry became a major industry in the area, with 39 brickworks active along the shores of the Waitematā Harbour, primarily on the shores of the Whau River.[82] From 1853, rural West Auckland around Glen Eden and Oratia was developed into orchards.[83] New Lynn developed as a trade centre after 1865 due to the port along the estuarial Whau River, which could only be used at high tide.[52] The North Auckland Line began operating in March 1880, connecting central Auckland to stations at Avondale, New Lynn and Glen Eden.[84] The line was extended to Henderson by December, and to Helensville by July 1881.[84] The railway encouraged growth along the corridor between Auckland and Henderson.[2]

The West Auckland orchards prospered in the early 1900s after immigrants from Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia) settled in the area.[2] In 1907, Lebanese New Zealander Assid Abraham Corban developed a vineyard at Henderson.[85] By the 1920s, the Lincoln Road, Swanson Road and Sturges Road areas had developed into orchards run primarily by Dalmatian families,[86] and in the 1940s these families began establishing vineyards at Kumeū and Huapai.[2]

In the 1920s and 1930s, flat land throughout Hobsonville and Whenuapai was the site of an airfield development for the New Zealand Air Force. Whenuapai became the main airport for civilian aviation between 1945 and 1965.[2] The Northwestern Motorway was first developed as a way for passengers to more efficiently drive to the airport at Whenuapai,[87] with the first section opening in 1952.[88]

Waitākere Ranges dams and regional park

[edit]

By the late 19th century, Auckland City was plagued with seasonal droughts. A number of options were considered to counter this, including the construction of water reservoirs in the Waitākere Ranges. The first of these projects was the Waitākere Dam in the north-eastern Waitākere Ranges, which was completed in 1910.[89][23] Further reservoirs were constructed along the different river catchments in the Waitākere Ranges: the Upper Nihotupu Reservoir in 1923;[89] the Huia Reservoir in 1929;[90] and the Lower Nihotupu Reservoir in 1948.[89]

The construction of the Waitākere Dam permanently reduced the flow of the Waitākere River, greatly impacting the Te Kawerau ā Maki community at Te Henga / Bethells Beach.[65] Between the 1910s and 1950s, most members of Te Kawerau ā Maki moved away from their traditional rohe, in search of employment or community with other Māori.[65] After the construction of the dams, the Nihotupu and Huia areas reforested in native bush. The native forest left a strong impression on residents who lived in these communities, and was one of the major factors that sparked the campaign for the Waitākere Ranges to become a nature reserve.[91]

The Auckland Centennial Memorial Park, which opened in 1940,[91] was formed from various pockets of land that had been reserved by the Auckland City Council starting in 1895.[92] Titirangi resident Arthur Mead, the principal engineer who created the Waitākere Ranges dams, lobbied the city council and negotiated with landowners to expand the park. Owing to the efforts of Mead, the park had tripled in size by 1964, when it became the Waitākere Ranges Regional Park.[92]

Urban development

[edit]

By the early 1950s, four major centres had developed to the west of Auckland: New Lynn, Henderson, Helensville and Glen Eden. These areas had large enough populations to become boroughs with their own local government, splitting from the rural Waitemata County.[93] Over the next 20 years, the area saw an explosion in population, driven by the construction of the Northwestern Motorway and the development of low-cost housing at Te Atatū, Rānui and Massey.[2] By this time, the area was no longer seen as scattered rural communities, and had developed into satellite suburbs of Auckland.[94] The post-war years saw widespread migration of Māori from rural areas to West Auckland. This happened a second time in the 1970s, as urban Māori communities moved away from the inner suburbs of Auckland to areas such as Te Atatū.[95] In 1980, Hoani Waititi Marae opened in West Auckland, to serve the urban Māori population of West Auckland.[96] By the mid-2000s, West Auckland had the largest Ngāpuhi population in the country outside of Northland.[95] Similarly, areas such as Rānui and Massey developed as centres for Pasifika New Zealander communities.[2][97]

The New Zealand Brick Tile and Pottery Company diversified and expanded into china production to supply local markets and American troops during World War II. Under the name Crown Lynn, the company developed into the largest pottery in the Southern Hemisphere.[2] In 1963, LynnMall opened, becoming the first American-style shopping mall in New Zealand.[98] It quickly became a major centre for retail in Auckland. The Henderson Borough Council wanted to replicate this success, and in 1968 opened Henderson Square,[98] now known as WestCity Waitakere.

In 1975, West Auckland was connected to the North Shore when the Upper Harbour Bridge was constructed across the Upper Waitematā Harbour.[99] In the late 1980s, the Crown Lynn factory closed due to competition from overseas imports.[2]

Demographics

[edit]West Auckland covers 578.20 km2 (223.24 sq mi)[100][A] and had an estimated population of 334,476 as of June 2024,[101] with a population density of 578 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,500 inhabitants per square mile).

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 236,454 | — |

| 2013 | 252,567 | +0.95% |

| 2018 | 282,129 | +2.24% |

| Source: [102] | ||

West Auckland had a population of 282,129 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 29,562 people (11.7%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 45,675 people (19.3%) since the 2006 census.[103] There were 87,870 households,[104] comprising 140,004 males and 142,122 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.99 males per female, with 59,559 people (21.1%) aged under 15 years, 60,672 (21.5%) aged 15 to 29, 130,470 (46.2%) aged 30 to 64, and 31,434 (11.1%) aged 65 or older.[103]

Ethnicities were 54.5% European/Pākehā, 13.4% Māori, 16.6% Pacific peoples, 27.4% Asian, and 3.6% other ethnicities. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.[103]

The percentage of people born overseas was 38.0, compared with 27.1% nationally.[103]

Although some people chose not to answer the census's question about religious affiliation, 44.0% had no religion, 36.5% were Christian, 0.8% had Māori religious beliefs, 5.8% were Hindu, 3.1% were Muslim, 1.7% were Buddhist and 2.2% had other religions.[105]

Of those at least 15 years old, 56,526 (25.4%) people had a bachelor's or higher degree, and 33,417 (15.0%) people had no formal qualifications. 38,691 people (17.4%) earned over $70,000 compared to 17.2% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 117,069 (52.6%) people were employed full-time, 29,490 (13.2%) were part-time, and 9,642 (4.3%) were unemployed.[102]

| Name | Area (km2) |

Population | Density (per km2) |

Households | Median age | Median income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waitākere ward | 359.00 | 170,514 | 475 | 52,704 | 34.1 years | $33,600 |

| Whau ward | 26.85 | 79,356 | 2,956 | 24,675 | 34.4 years | $29,600 |

| West Harbour Luckens Point | 0.98 | 2,697 | 2,752 | 825 | 37.8 years | $37,700[106] |

| West Harbour Clearwater Cove | 1.36 | 4,344 | 3,194 | 1,371 | 41.2 years | $39,200[107] |

| Hobsonville | 2.17 | 1,173 | 541 | 399 | 37.0 years | $40,400[108] |

| Hobsonville Point | 3.54 | 3,765 | 1,064 | 1,413 | 34.5 years | $51,800[109] |

| Whenuapai | 19.68 | 3,888 | 198 | 1,263 | 34.8 years | $43,800[110] |

| Kumeu Rural East | 14.92 | 2,028 | 136 | 594 | 43.2 years | $35,200[111] |

| Taupaki | 27.20 | 1,617 | 59 | 525 | 43.1 years | $37,200[112] |

| Riverhead | 4.05 | 2,802 | 692 | 864 | 35.2 years | $52,600[113] |

| Kumeu-Huapai | 6.32 | 3,432 | 543 | 1,110 | 34.9 years | $47,800[114] |

| Kumeu Rural West | 24.43 | 1,626 | 67 | 528 | 43.4 years | $38,300[115] |

| Waimauku | 5.63 | 1,338 | 238 | 426 | 40.4 years | $45,400[116] |

| Waipatukahu | 52.06 | 1,461 | 28 | 471 | 40.1 years | $40,500[117] |

| Muriwai | 3.01 | 1,248 | 415 | 444 | 40.1 years | $45,700[118] |

| 7002136 | 8.89 | 222 | 25 | 66 | 34.8 years | $39,600[B] |

| 7002135 | 4.26 | 177 | 42 | 54 | 41.2 years | $37,200 |

| 7002139 | 2.75 | 117 | 43 | 36 | 32.9 years | $36,300 |

| 7002148 | 7.20 | 132 | 18 | 42 | 42.2 years | $44,400 |

| 7002147 | 3.90 | 192 | 49 | 60 | 38.6 years | $38,800 |

| New Zealand | 37.4 years | $31,800 |

- ^ In this section, West Auckland is treated as including Waitākere and Whau wards and the parts of Rodney and Albany wards listed in the table of individual statistical areas.

- ^ The statistical area of Muriwai Valley-Bethells Beach is partly in Waitākere Ward, so only those areas outside that ward are included. These smaller areas do not have names in the census results, only numbers.

Landmarks and features

[edit]Notable buildings and sites

[edit]

- Corban Estate Arts Centre – a former vineyard and current centre for arts located in Henderson[119]

- Glen Eden Playhouse Theatre – a historic community theatre[120]

- Hoani Waititi Marae – the first urban marae built in New Zealand,[121] and a centre for Māori language, culture and practice

- Hollywood Cinema – a historic cinema in Avondale[122]

- RNZAF Base Auckland – a large base of the Royal New Zealand Air Force in Whenuapai[123]

- St Jude's Church and Hall – a Gothic-revival Anglican church built in 1884[124]

- Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery – a contemporary art gallery located in Titirangi[125]

- Waiatarua TV Transmitter – a former analogue television transmission mast in Waiatarua,[126] located near the highest point of the eastern Waitākere Ranges

- Waikumete Cemetery in Glen Eden – the largest cemetery in New Zealand, which was established in 1886 as a cemetery for Auckland, and includes the historic Chapel of Faith in the Oaks, a large nature reserve and a memorial for the 1918 flu pandemic[127]

- Watyarnprateep Buddhist Temple – a centre for Thai Buddhism in Kelston[128]

Natural areas

[edit]

- The Waitākere Ranges – a regional park and the remnants of a Miocene volcano. The ranges feature a number of water reserves, including the Lower Nihotupu Reservoir and the Waitākere Reservoir,[58][23] the Ark in the Park conservation project,[129] the Arataki Visitor Centre[130] and locations such as the Kitekite Falls.[131]

- Te Wai-o-Pareira / Henderson Creek – an estuarial arm of the Waitematā Harbour that covers the catchment for much of West Auckland. Since the early 2000s, an initiative called Project Twin Streams has worked on restoring forests and creating walkways and cycleways along the catchment.[132]

- The Whau River – an estuarial arm of the Waitematā Harbour. The Whau River is the location of the Te Whau coastal pathway, which has been under construction since 2015.[133]

- The west coast beaches, including Muriwai, Te Henga / Bethells Beach, Piha, Karekare and Whatipu. The Tasman Sea beaches of Auckland have iron-rich black sand, which originated from volcanic eruptions.[134]

Education

[edit]

The first schools that began operating in West Auckland were Avondale School, which opened in 1860,[135] a school held in the library of Henderson's Mill in 1873,[136] and the New Lynn School, which opened on the modern site of Kelston Girls' College in 1888.[137]

West Auckland has a number of co-educational secondary schools, including Avondale College, one of the largest high schools in New Zealand with a roll of 2834 students.[138] Other state co-educational schools include Massey High School (1839 students),[139] Henderson High School (1056 students),[140] Waitakere College (1828 students),[141] Rutherford College (1432 students),[142] Hobsonville Point Secondary School (854 students)[143] and Green Bay High School (1761 students).[144] The first private secondary school in West Auckland, ACG Sunderland School and College, opened in 2007 at the former site of the Waitakere City Council buildings,[145] and has a roll of 828 students.[146]

West Auckland is also home to four single-sex secondary schools: Kelston Boys' High School (745 students)[147] and Kelston Girls' College (503 students),[148] and the state-integrated Catholic schools Liston College and St Dominic's College, which have rolls of 841 and 805 students, respectively.[149][150]

Transportation

[edit]West Auckland has been served by railway since the late 19th century. The North Auckland Line first opened in 1880, and was extended to Helensville by 1881.[84] The train line is operated as the Western Line, which operates passenger services between Swanson and Britomart in the Auckland city centre.

The Northwestern Motorway opened between central Auckland and Te Atatū in 1952, encouraging growth around the western Waitematā Harbour.[88] The Southwestern Motorway, which borders West Auckland, became connected directly to the Northwestern Motorway when the Waterview Connection opened to traffic in July 2017.[151] The first stages of the Northwestern Busway, a project that was first envisioned as a light rail line adjacent to the Northwestern Motorway, are currently under construction.[152] In addition to the motorways, major roads in West Auckland include Great North Road, Don Buck Road, Lincoln Road, West Coast Road, Swanson Road, Scenic Drive and Portage Road.

Two ferry terminals in West Auckland, at West Harbour and Hobsonville, operate commuter ferry services to the Auckland city centre.[153]

Amenities

[edit]

West Auckland is home to a number of large urban parks, including Parrs Park, Moire Park,[154] Henderson Park,[155] Tui Glen Reserve[156] and Olympic Park.[157] Many professional and amateur sports teams are based in West Auckland, including: the Waitakere Cricket Club; rugby league teams Glenora Bears, the Waitemata Seagulls[158] and Te Atatu Roosters; an ice hockey team, the West Auckland Admirals; and a number of association football teams, including Bay Olympic who as of 2022 play in the Northern League.[159]

The Trusts Arena, a multi-purpose stadium in Henderson, regularly hosts large-scale sporting events and concerts.[160] The Avondale Racecourse is both a venue for Thoroughbred racing, and the home of the Avondale Sunday Markets, one of the largest regular markets in New Zealand.[161][162] Other large amenities in West Auckland include the Paradice Ice Skating rink in Avondale,[163] West Wave Pool and Leisure Centre in Henderson,[164] and the Titirangi Golf Club.[165] In the 1980s, Te Atatū Peninsula was the site of Footrot Flats Fun Park, a large-scale amusement park that closed in 1989.[166]

LynnMall, the first American-style shopping centre in New Zealand, opened in 1963.[167] Other major shopping areas in West Auckland include the NorthWest Shopping Centre in Westgate, and WestCity Waitakere in Henderson. The first Costco store in New Zealand opened at Westgate in 2022.[168]

Notable people

[edit]

- Edith Amituanai – Samoan New Zealand contemporary artist based in Rānui[169]

- Paula Bennett – deputy prime minister from 2016 to 2017[170]

- Simon Bridges – leader of the opposition from 2018 to 2020, who grew up in Te Atatū[171]

- Don Buck – Portuguese New Zealand gumdigger in the early 19th century[172]

- Maurice Gee – author[173]

- Ewen Gilmour – comedian[174]

- Bob Harvey – mayor of Waitakere City from 1992 to 2010[175]

- Oscar Kightley – Samoan New Zealand actor and comedian[176]

- Cindy Kiro – public health academic, and governor-general since 2021[177]

- Colin McCahon – artist who lived in Titirangi in the 1950s[178][179]

- Rose McIver – actress who grew up in Titirangi[180]

- Paul Radisich – Croatian New Zealand racing driver[176]

- Ian Scott – artist[181]

- Maurice Shadbolt – author[179]

- Va'aiga Tuigamala – Samoan New Zealand rugby union and rugby league player[182]

- Karen Walker – fashion designer[176]

Local government

[edit]

Road boards were the first local government in West Auckland, established across the Auckland Province in the 1860s due to a lack of central government funding for road improvements.[183] In West Auckland, some of these bodies included the Whau Highway Board, the Titirangi Road Board, Waikumete Road Board, Waipareira Road Board and the Waitakere East, South and West Road Boards.[184] In 1876, the Waitemata County was established as the local government of West Auckland, the North Shore and Rodney, becoming one of the largest counties ever created in New Zealand.[185] In 1881, the Town District Act allowed communities of more than 50 households to amalgamate into a town district. Large town districts were able to form boroughs, which had their own councils and a greater lending power.[185] Between 1886 and 1954, nine boroughs split from the county as Auckland began to develop, primarily on the North Shore.[93] In West Auckland, the first borough to form was New Lynn in 1929, followed by Henderson in 1946, Helensville in 1947 and Glen Eden in 1953.[93]

On 1 August 1974, the western area of Waitemata County amalgamated to form the Waitemata City, which included Titirangi, Te Atatū, Lincoln and Waitākere, without the boroughs of New Lynn, Henderson and Glen Eden.[186] Henderson Borough refused to amalgamate into the city, preferring to retain its unique identity, while the New Lynn and Glen Eden borough councils were interested but were unable to meet the deadline for the merger.[186] Tim Shadbolt, later known as the mayor of Invercargill, was the longest serving mayor of Waitemata City (1983–1989).[187]

With the 1989 local government reforms, the Waitemata City merged with the New Lynn, Glen Eden and Henderson boroughs to form the Waitakere City.[188] In the early years of the city's existence, the Rosebank Peninsula was proposed to be added to the city, however this was opposed by mayor Assid Corban.[188] From 1992 to 2010, Bob Harvey served as the mayor of Waitakere City.[189]

On 1 November 2010, Waitakere City was merged with the surrounding metropolitan and rural areas of Auckland to form a single Auckland Council unitary authority.[190] Within the new system, West Auckland was primarily split into three areas which elect a local board: Henderson-Massey, the Waitākere Ranges and Whau. The Whau local board area includes the suburbs of Avondale, New Windsor and Rosebank; areas to the east of the Whau River formerly administered as a part of Auckland City.[191] Northern West Auckland suburbs such as Whenuapai and Hobsonville, formerly administered by the Waitakere City, became a part of the Upper Harbour local board area, which also covers Albany and much of the North Shore. North-western towns such as Riverhead, Kumeū and Huapai became a part of the Rodney local board area.

In addition to local boards, a number of councillors represent West Auckland on the Auckland Council. Voters in the Henderson-Massey and Waitākere Ranges areas vote for two councillors as a part of the Waitākere ward,[192] while people in the Whau local board area vote for a single Whau ward councillor.[193] Upper Harbour residents vote for two Albany ward councillors,[194] while Rodney residents vote for one councillor to represent the Rodney ward.[195]

References

[edit]- ^ "Tania Pouwhare". Waatea News. 1 November 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m McClure, Margaret (1 August 2016). "West Auckland". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Historic District Schemes and Plans of the Auckland Region". Auckland Council. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Earley, Melanie (30 June 2022). "More than 500 homes planned for West Auckland's Avondale". Stuff. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "School Directory". Waitakere Area Principals' Association. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Covid 19 Delta outbreak: Outdoor gym classes identified as new locations of interest". The New Zealand Herald. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Bloomfield 1973, pp. 55.

- ^ Stone 2001, pp. 48.

- ^ Luxton 2006, pp. 271.

- ^ "West Auckland AT HOP retailers". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Proposed changes to West Auckland bus services Consultation Brochure" (PDF). Auckland Transport. 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Wade, Pamela (17 January 2022). "How to spend a perfect weekend in West Auckland". Stuff. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Huakau, John (July 2016). Locality Population Snapshot West Auckland (PDF) (Report). Te Pou Matakana. ISBN 978-0-473-31576-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Martin, Sam; Zhou, Lifeng (October 2012). West Auckland Integrated Care Project: Locality and Cluster Level Analysis (PDF) (Report). Waitematā District Health Board. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Moore, Charlie; Bridgman, Geoff; Moore, Charlotte; Grey, Jeff (March 2017). Perceptions of Community Safety in West Auckland (PDF) (Report). Community Waitakere. ISBN 978-0-473-39286-4. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Murdoch 1990, pp. 18.

- ^ Diamond & Hayward 1979, pp. 41.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 23.

- ^ a b c d "Te Kawerau ā Maki Deed of Settlement Schedule" (PDF). New Zealand Government. 22 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Murdoch 1990, pp. 20.

- ^ a b Murdoch 1990, pp. 12.

- ^ Tatton, Kim (June 2019). The Historic Māori Settlements of Waiti Village and Parawai Pā, Te Henga: Research Report (PDF). Auckland Council. ISBN 978-0-908320-17-2. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Waitākere Ranges Local Board (October 2015). Local Area Plan: Te Henga (Bethells Beach) and the Waitākere River Valley. Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area (PDF). Auckland Council. ISBN 978-0-908320-17-2. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "City Plan Rejected". Press. Vol. CIII, no. 30623. 14 December 1964. p. 14. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Control by trusts". Press. Vol. CXI, no. 32752. 1 November 1971. p. 16. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Changes in Auckland". Press. Vol. CXIV, no. 33664. 14 October 1974. p. 1. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "The Territorials". The New Zealand Herald. Vol. XLVIII, no. 14730. 12 July 1911. p. 4. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Liberal and Labour Federation". Auckland Star. Vol. XXXVII, no. 51. 28 February 1906. p. 6. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Power Supply Fails". The New Zealand Herald. Vol. LXV, no. 19845. 16 January 1928. p. 8. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ "Western Auckland". The New Zealand Herald. Vol. XLIV, no. 13474. 26 June 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 28 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ Simpson, K. A. "Hobson, William". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ "Westies Up Front Out There" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2006. Retrieved 26 January 2023..

- ^ Walker, Zoe (16 December 2010). "Ways of the Wests: Outrageous Fortune the exhibition". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Frew, Jae; Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Westies". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hayward 2009, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Hayward 2009, pp. 8.

- ^ Hayward 2017, pp. 109.

- ^ Hayward 2009, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d Hayward 2009, pp. 13–14, 17–18.

- ^ "Estuary origins". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Cranwell-Smith 2006, pp. 49.

- ^ Esler 2006, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Jones 2006, pp. 97.

- ^ Grant 2009, pp. 315–318.

- ^ a b c d "Native to the West: A Guide for Planting and Restoring the Nature of Waitakere City" (PDF). Waitakere City Council. April 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Hatch 2006, pp. 99.

- ^ a b c State of the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area 2018: 2 Topic: Indigenous terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (PDF) (Report). Auckland Council. May 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "History of Ark in the Park". Nature Space. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Grant 2009, pp. 318–321.

- ^ Ternouth, Louise (30 January 2024). "New species of Gecko on Auckland's West Coast named". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Waikumete Stream" (PDF). Project Twin Streams. Auckland Council. 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2022..

- ^ a b "The Whau: Our Streams, Our River, Our Backyards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2023..

- ^ McQueen, Stella (2010). The New Zealand Native Freshwater Aquarium. New Zealand: Wet Sock Publications. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780473179359..

- ^ a b Taua 2009, pp. 27–31.

- ^ Pishief, Elizabeth; Shirley, Brendan (August 2015). "Waikōwhai Coast Heritage Study" (PDF). Auckland Council. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Taonui, Rāwiri (10 February 2015). "Tāmaki tribes". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "The Rāhui". Waitākere Rāhui. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b "The Muddy Creeks Plan – a Local Area Plan for Parau, Laingholm, Woodlands Park and Waimā" (PDF). Auckland Council. 13 February 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Karangahape Peninsula". New Zealand Gazetteer. Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Murdoch 1990, pp. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Diamond & Hayward 1990, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Diamond & Hayward 1990, pp. 23, 38–39.

- ^ Diamond & Hayward 1990, pp. 33.

- ^ Diamond & Hayward 1990, pp. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Taua 2009, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Paterson 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Diamond & Hayward 1979, pp. 14.

- ^ Te Ākitai Waiohua (2015). "Cultural impact assessment by Te Ākitai Waiohua for Bremner Road Drury Special Housing Area" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2021 – via Auckland Council.

- ^ Stone 2001, pp. 42.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 37.

- ^ a b Taua 2009, pp. 39.

- ^ Taua 2009, pp. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Redman, Julie (2007). "Auckland's first settlement at Cornwallis 1835–1860". New Zealand Legacy. 19 (2): 15–18.

- ^ "The Corn Wallis Settlement". The New Zealand Herald. Papers Past. 4 November 1892. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Mogford, Janice C. "A summary of Onehunga's European settlement". The Onehunga Business Association. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Stone 2001, pp. 180.

- ^ Thomas, Carolyn (8 June 2009). "Mill artefacts go on display". Stuff. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b Hayward 1989, pp. 5.

- ^ a b Diamond 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Vela 1989, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c Scoble, Juliet (2010). "Names & Opening & Closing Dates of Railway Stations" (PDF). Rail Heritage Trust of New Zealand. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Flude 2008, pp. 66.

- ^ Flude 2008, pp. 77, 79–80.

- ^ Lancaster & La Roche 2011, pp. 110–116.

- ^ a b "About the City". Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2023..

- ^ a b c La Roche 2011, pp. 27–50.

- ^ "Huia Dam Township Now Being Removed". Vol. III, no. 788. Auckland Sun. 8 October 1929. p. 7. Retrieved 5 July 2022 – via Papers Past.

- ^ a b Harvey & Harvey 2009, pp. 97.

- ^ a b Grant 2009, pp. 313–315.

- ^ a b c Reidy 2009, pp. 239.

- ^ Vela 1989, pp. 85–87.

- ^ a b Stewart 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Stewart 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Stewart 2009, p. 115.

- ^ a b Moon 2009, pp. 136.

- ^ Reidy 2009, pp. 245.

- ^ "ArcGIS Web Application". statsnz.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "Aotearoa Data Explorer". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Waitakere Ward (07604), Whau Ward (07606), West Harbour Luckens Point (120700), West Harbour Clearwater Cove (120300), Hobsonville (119200), Hobsonville Point (120200), Whenuapai (117000), Kumeu Rural East (116100), Taupaki (116400), Riverhead (115900), Kumeu-Huapai (115000), Kumeu Rural West (114700), Waimauku (114200), Waipatukahu (113200), Muriwai (114500), 7002136 (7002136), 7002135 (7002135), 7002139 (7002139), 7002148 (7002148) and 7002147 (7002147).

- ^ a b c d "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Individual_part1_totalNZ-wide_format_updated_12-3-20.csv.

- ^ "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Households_totalNZ-wide_format_updated_12-3-20.csv.

- ^ "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Individual_part2_totalNZ-wide_format_updated_12-3-20.csv.

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: West Harbour Luckens Point

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: West Harbour Clearwater Cove

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Hobsonville

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Hobsonville Point

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Whenuapai

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Kumeu Rural East

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Taupaki

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Riverhead

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Kumeu-Huapai

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Kumeu Rural West

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Waimauku

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Waipatukahu

- ^ 2018 Census place summary: Muriwai

- ^ Foxcroft, Debrin (8 March 2018). "Corbans Estate Arts Centre open to wine museum idea". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Smith, Simon (23 June 2017). "The big sound of the Wurlitzer organ to entertain once more". Stuff. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Clent, Danielle (31 January 2018). "West Auckland's Waitangi Day celebration likely to attract 20,000 people". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Reed, Chris (17 November 2019). "Gig review: The Beths at The Hollywood Avondale". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Quinn, Rowan (14 February 2019). "'Frustrating wait': Noise from Defence Force planes delays new homes". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "St Jude's Church and Hall". Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Ahwa, Dan (4 October 2022). "Style Liaisons: In Conversation With Gallery Director Andrew Clifford". Viva. The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Diamond, J.T. "New TV tower, Waiatarua". Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Vela 1989, pp. 30–37.

- ^ Tischler, Monica (15 December 2014). "Faces of Auckland:Monk's peaceful life". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Rees-Owen, Rose (18 February 2016). "Ark in the Park tackle wasps in the Waitakere Ranges". Stuff. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Visit Auckland's regional parks this summer". OutAuckland. Auckland Council. 20 December 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Cheeky long weekend: Piha". The New Zealand Herald. 3 November 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ Gregory, Angela (10 September 2007). "Waitakere streams second only to Danube in international contest". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Wilkinson, Caryn (22 December 2020). "Residents to appeal $69 million Auckland pathway". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Ingram 2011, p. 245–261.

- ^ Dickey 2020, pp. 29.

- ^ Flude 2008, pp. 27.

- ^ Skelton 2016, pp. 49.

- ^ Education Counts: Avondale College

- ^ Education Counts: Massey High School

- ^ Education Counts: Henderson High School

- ^ Education Counts: Waitakere College

- ^ Education Counts: Rutherford College

- ^ Education Counts: Kelston Boys' High School

- ^ Education Counts: Green Bay High School

- ^ Devaliant 2009, p. 214.

- ^ Education Counts: Sunderland College

- ^ Education Counts: Kelston Boys' High School

- ^ Education Counts: Kelston Girls College

- ^ Education Counts: Liston College

- ^ Education Counts: St Dominic's College

- ^ "Auckland's Waterview Tunnel open to traffic at last". Stuff. 2 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Niall, Todd (10 February 2022). "$50m West Auckland busway delayed up to nine months by Covid-19, building hold-ups". Stuff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Niall, Todd (15 July 2022). "Auckland's ferries to be publicly owned in $100m shake-up of transport services". Stuff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Niall, Todd (30 March 2022). "How to make our cities cooler as temperatures rise". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Greco, Shelley (25 September 2014). "Family excited over new frisbee golf course". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Collins, Simon (18 June 2015). "Living rough in the wild west". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Local govt stalwart a believer in service". The New Zealand Herald. 10 October 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Raethel, Julian (21 August 2012). "Glenora must wait till next season". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Fresh look as Bay Olympic updates its club logo for 25th anniversary". Friends of Football. 15 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Trusts Arena". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Stephenson, Sharon (26 February 2022). "Three of Auckland's best farmers' markets". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Milne, Jonathan (4 July 2022). "Urban renewal: A tale of two Avondales". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Sivertsen, Juliette (7 July 2020). "Go NZ: Best places to ice skate in New Zealand". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Tokalau, Torika (13 December 2020). "'Major leak' forces large Auckland pool complex to part close". Stuff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand's finest 40 golf courses revealed". Stuff. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Schulz, Chris (28 May 2022). "'Disneyland of the Pacific': The rise and fall of West Auckland's Footrot Flats Fun Park". The Spinoff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Fifty years of the shopping mall". Stuff.co.nz. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Lucy (28 September 2022). "Shoppers flock to new Costco store in Auckland on opening day". 1News. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Lopesi, Lana (2018). "Beyond essentialism: Contemporary Moana art from Aotearoa New Zealand". Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry. 46 (1): 106–115. doi:10.1086/700252. ISSN 1465-4253. S2CID 191521987.

- ^ Knight, Kim (28 August 2022). "The reinvention of Paula Bennett: Private wealth, a new podcast and the art of the 'no comment'". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Dudding, Adam (25 September 2008). "Tauranga: you are now entering Winston country". Sunday Star Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ Simpkins, Marianne (1993). "Figueira, Francisco Rodrigues". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Matthews, Philip (6 October 2018). "Maurice Gee on his mother's thwarted writing career, his messy adolescence and how he met the love of his life". Stuff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ McAllen, Jess (3 October 2014). "Comedian Ewen Gilmour dies". Stuff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Reilly, Rebecca K (10 July 2022). "The Sunday Essay: In memory of Waitākere City (1989-2010)". The Spinoff. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "West celebs immortalised in granite". Western Leader. 31 January 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Hewitson, Michelle (15 August 2003). "A horribly good voice for the kids". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Harvey & Harvey 2009, pp. 102.

- ^ a b Gibson, Anne (9 April 2022). "A tale of two houses: Shadbolt, McCahon - two people's determination to fulfil a dream". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Rose McIvor: taking on Tinseltown". NZ Woman's Weekly. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Milford Galleries Dunedin (2013). Ian Scott Lattices. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Logan 2009, pp. 411–432.

- ^ "Previous Local Government Agencies". Auckland Council. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Road Boards: Auckland Council's Ancestors" (PDF). Auckland Council. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b Reidy 2009, pp. 238.

- ^ a b Reidy 2009, pp. 242.

- ^ Reidy 2009, pp. 245–248.

- ^ a b Reidy 2009, pp. 249.

- ^ "Report of the Mayor" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2022..

- ^ Blakeley, Roger (2015). "The planning framework for Auckland 'super city': an insider's view". Policy Quarterly. 11 (4). doi:10.26686/pq.v11i4.4572. ISSN 2324-1101.

- ^ "Council profile". aucklandcouncil.govt.nz. Auckland Council.

- ^ Council, Auckland. "Waitākere Ward". Auckland Council. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Council, Auckland. "Whau Ward". Auckland Council. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Council, Auckland. "Albany Ward". Auckland Council. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Council, Auckland. "Rodney Ward". Auckland Council. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bloomfield, G.T. (1973). The Evolution of Local Government Areas in Metropolitan Auckland, 1840–1971. Auckland University Press, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-647714-X.

- Cranwell-Smith, Lucy (2006). "Rain Forest of the Waitakeres". In Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (eds.). Waitakere Ranges: Ranges of Inspiration, Nature, History, Culture. Waitakere Ranges Protection Society. ISBN 978-0-476-00520-4.

- Devaliant, Judith (2009). "History Lessons". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Diamond, John T. (1992). "The Brick and Pottery Industry in the Western Districts". In Northcote-Bade, James (ed.). West Auckland Remembers, Volume 2. West Auckland Historical Society. ISBN 0-473-01587-0.

- Diamond, John T.; Hayward, Bruce W. (1979). The Māori history and legends of the Waitākere Ranges. The Lodestar Press. ISBN 9781877431210.

- Diamond, John T.; Hayward, Bruce W. (1990). "Prehistoric Sites in West Auckland". In Northcote-Bade, James (ed.). West Auckland Remembers, Volume 1. West Auckland Historical Society. pp. 33–41. ISBN 0-473-00983-8.

- Dickey, Hugh (2020). Whau Now, Whau Then. Blockhouse Bay Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-473-54013-5.

- Esler, Alan (2006). "Forest Zones". In Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (eds.). Waitakere Ranges: Ranges of Inspiration, Nature, History, Culture. Waitakere Ranges Protection Society. ISBN 978-0-476-00520-4.

- Flude, Anthony G. (2008). Henderson's Mill: a History of Henderson 1849-1939. West Auckland Historical Society. ISBN 9781877431210.

- Grant, Simon (2009). "Call of the Wild". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 305–322. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (2009). "That Noble Sheet of Water". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 87–104. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Hatch, J. D. (2006). "Native Orchids". In Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (eds.). Waitakere Ranges: Ranges of Inspiration, Nature, History, Culture. Waitakere Ranges Protection Society. ISBN 978-0-476-00520-4.

- Hayward, Bruce W. (1989). Kauri Gum and the Gumdiggers. The Bush Press. ISBN 0-908608-39-X.

- Hayward, Bruce W. (2009). "Land, Sea and Sky". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 7–22. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Hayward, Bruce W. (2017). Out of the Ocean, Into the Fire. Geoscience Society of New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-473-39596-4.

- Ingram, John (2011). "Steel from Ironsand". In La Roche, John (ed.). Evolving Auckland: The City's Engineering Heritage. Wily Publications. pp. 245–261. ISBN 9781927167038.

- Jones, Sandra (2006). "Uncommon Trees and Shrubs of the Waitakeres". In Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (eds.). Waitakere Ranges: Ranges of Inspiration, Nature, History, Culture. Waitakere Ranges Protection Society. ISBN 978-0-476-00520-4.

- Lancaster, Mike; La Roche, John (2011). "Auckland Motorways". In La Roche, John (ed.). Evolving Auckland: The City's Engineering Heritage. Wily Publications. ISBN 9781927167038.

- La Roche, John (2011). "Auckland's Water Supply". In La Roche, John (ed.). Evolving Auckland: The City's Engineering Heritage. Wily Publications. ISBN 9781927167038.

- Logan, Innes (2009). "Game On". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Luxton, David (2006). "Timber, Clay and Gum". In Harvey, Bruce; Harvey, Trixie (eds.). Waitakere Ranges: Ranges of Inspiration, Nature, History, Culture. Waitakere Ranges Protection Society. pp. 270–282. ISBN 978-0-476-00520-4.

- Moon, Paul (2009). "Taking Care of Business". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 119–140. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Murdoch, Graeme (1990). "Nga Tohu o Waitakere: the Maori Place Names of the Waitakere River Valley and its Environs; their Background History and an Explanation of their Meaning". In Northcote-Bade, James (ed.). West Auckland Remembers, Volume 1. West Auckland Historical Society. pp. 9–32. ISBN 0-473-00983-8.

- Paterson, Malcolm (2009). "Ko Ngā Kurī Purepure o Tāmaki, e Kore e Ngari i te Pō". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 49–62. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Reidy, Jade (2009). "How the West Was Run". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 237–256. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Skelton, Carolyn (2016). A Brief History of New Lynn: A West Auckland suburb. Auckland Libraries West Auckland Research Centre, Whau Local Board.

- Stewart, Keith (2009). "Into the West". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 105–118. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Stone, R. C. J. (2001). From Tamaki-makau-rau to Auckland. Auckland University Press. ISBN 1869402596.

- Taua, Te Warena (2009). "He Kohikohinga Kōrero mō Hikurangi". In Macdonald, Finlay; Kerr, Ruth (eds.). West: The History of Waitakere. Random House. pp. 23–48. ISBN 9781869790080.

- Vela, Pauline, ed. (1989). In Those Days: An Oral History of Glen Eden. Glen Eden Borough Council. ISBN 0-473-00862-9.