Waldorf-Astoria (1893–1929)

| Waldorf-Astoria | |

|---|---|

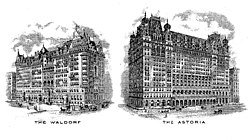

Engraved vignettes of the original hotels c. 1915 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Hotel |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival architecture |

| Address | 5th Avenue and West 34th Street |

| Town or city | New York, New York (Manhattan) |

| Country | U.S. |

| Opened |

|

| Demolished | 1929 (the Empire State Building replaced the buildings on the same site, while the Waldorf Astoria New York was rebuilt at another location) |

| Cost | $4.5 million ($126 million in 2017) |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 226 feet (69 m) (Waldorf), 269 feet (82 m) (Astoria) |

| Floor count | 13 (Waldorf), 16 (Astoria) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Henry Janeway Hardenbergh |

The Waldorf-Astoria originated as two hotels, built side by side by feuding relatives, on Fifth Avenue in New York, New York, United States. Built in 1893 and expanded in 1897, the hotels were razed in 1929 to make way for construction of the Empire State Building. Their successor, the current Waldorf Astoria New York, was built on Park Avenue in 1931.

The original Waldorf Hotel opened on March 13, 1893, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, on the site where millionaire developer William Waldorf Astor had previously built his mansion. Constructed in the German Renaissance style by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, it stood 225 feet (69 m) high, with fifteen public rooms and 450 guest rooms, and a further 100 rooms allocated to servants, with laundry facilities on the upper floors. It was heavily furnished with antiques purchased by founding manager and president George Boldt and his wife during an 1892 visit to Europe. The Empire Room was the largest and most lavishly adorned room in the Waldorf, and soon after opening it became one of the best restaurants in New York, rivaling Delmonico's and Sherry's.

The Astoria Hotel opened in 1897 on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, next door to the Waldorf. It was also designed in the German Renaissance style by Hardenbergh, at a height of about 270 feet (82 m), with sixteen stories, twenty-five public rooms and 550 guest rooms. The ballroom, in the Louis XIV style, has been described as the "pièce de résistance" of the hotel, with a capacity to seat 700 at banquets and 1,200 at concerts. The Astor Dining Room was faithfully reproduced from the original dining room of the mansion which once stood on the site.

Connected by the 300 metres (980 ft) long corridor, known as "Peacock Alley" after the merger in 1897, the hotel had 1,300 bedrooms, making it the largest hotel in the world at the time. It was designed specifically to cater to the needs of socially prominent "wealthy upper crust" of New York and distinguished foreign visitors to the city. It was the first hotel to offer electricity and private bathrooms throughout. The Waldorf gained world renown for its fundraising dinners and balls, as did its celebrity maître d'hôtel, Oscar Tschirky, known as "Oscar of the Waldorf". Tschirky authored The Cookbook by Oscar of The Waldorf (1896), a 900-page book featuring recipes that remain popular worldwide today.

Background

[edit]

Opening and early years of the Waldorf

[edit]In 1799, John Thompson bought a 20-acre (8 ha) tract of land roughly bounded by Madison Avenue, 36th Street, Sixth Avenue, and 33rd Street, immediately north of the Caspar Samler farm, for (US$2400) £482 10s.[1] In 1826, John Jacob Astor purchased Thompson's parcel, as well as one from Mary and John Murray who owned a farm on Murray Hill, in the area which is now Madison Avenue to Lexington Avenue, between 34th and 38th streets.[2][a] In 1827, William B. Astor, Sr. bought a half interest, including Fifth Avenue from 32nd to 35th streets, for $20,500. He built an unpretentious square red brick house on the southwest corner of 34th Street and Fifth Avenue, while John Jacob Astor erected a home at the northwest corner of 33rd Street.[4]

William Waldorf Astor, motivated in part by a dispute with his aunt Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, built the Waldorf Hotel next door to her house, on the site of his father's mansion at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street.[b] After Astor's decision to leave the United States, he also decided to demolish his father's home and build a hotel on the property.[6] When the 1870 Astor home was demolished, there was no idea that Astor would build a hotel on the property.[7] Astor did not stay in his own hotel when visiting the U.S., preferring to stay elsewhere; he is known to have visited the Waldorf-Astoria only once.[8]

The hotel was built to the specifications of the founding proprietor George Boldt, who owned and operated the elite Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia with his wife, Louisa Augusta Kehrer Boldt (1860–1904). The original plans for the Waldorf were for a hotel with eleven stories; Louise believed that thirteen was a lucky number and persuaded her husband to add two floors to the construction.[9][c] William Astor's construction of a hotel next to his aunt's house worsened his feud with her, but, with Boldt's assistance, John Astor persuaded his mother to move uptown.[10][d] The Waldorf Hotel, named after the Astor family's ancestral hometown of Walldorf, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, was opened for business March 13, 1893.[12]

Early on, the Waldorf was regarded with mockery over its large number of bathrooms and was known briefly as "Boldt's Folly" after Boldt, or "Astor's Folly",[13] with the general perception of the palatial hotel being that it had no place in New York.[14] It appeared destined for failure. Wealthy New Yorkers were angry because they viewed the construction of the hotel as the ruination of a good neighborhood. Business travelers found it too expensive and too far uptown for their needs. In the face of all of this, Boldt decided that the hotel would host a benefit concert for St. Mary's Hospital for Children the day after its opening.[12] The hospital was the favorite charity of those on the Social Register. Despite the rain the night of the ball, the ballroom filled with many of New York's First Families, who had paid $5.00 ($170.00 in 2023[15]) for the concert and dinner.[16][e] Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt donated the services of the New York Symphony Orchestra led by Walter Damrosch to provide the music for the event.[16] Even with a proper escort, women of the times generally did not venture into hotels, but those attending also toured the facilities.[18] While Boldt made news by insisting the Waldorf's waiters be clean-shaven even though he wore a beard, his decision to hire young Oscar Tschirky was one of the key factors in the hotel's success.[19][f] Oscar was personable, humble and very willing to tend to patrons' needs on an individual basis.[18] More than thirty years later, Tschirky was able to recall the Waldorf's opening day and the names of many of the Social Register guests who made the hotel successful when it hosted the charity concert and dinner.[20][21] Business soon picked up and the hotel earned $4.5 million ($137 million in 2023[22]) in its first year, exorbitant for that period.[23] By 1895, the Waldorf added a five-story addition. This brought the hotel's ballroom down to the main floor; the move brought many parties and dinners which were formerly held in private homes, into the Waldorf. Adjacent to the new ballroom was the Oak Room, where one could sit by large fireplaces where there were always logs on the hearth. In winter, waiters would offer patrons complimentary baked potatoes with butter.[24]

Opening of the Astoria and consolidation

[edit]

When a decision was made to build a second hotel next to the Waldorf, truce provisions were developed between the Astors which reserved some proprietary rights. The plan design used corridors to join the two buildings and there was even a bond provision for bricking up the corridors should the need arise.[25] On November 1, 1897, Waldorf's cousin, John Jacob Astor IV, opened the 16 story Astoria Hotel on an adjacent site.[26][27] The Astoria, named after Astoria, Oregon which was founded by John Jacob Astor in 1811, stood on the site of William B. Astor's house, and was leased to Boldt.[28][26]

The two hotels, under one management, were renamed the Waldorf-Astoria.[29][30] Situated on Fifth Avenue in what is now Midtown Manhattan, it was surrounded by streets on all sides. The Waldorf-Astoria had a frontage of 200 feet (61 m) on Fifth Avenue, 350 feet (110 m) on 33rd Street, 350 feet (110 m) on 34th Street, and 200 feet (61 m) on Astor Court, with 13 entrances opening directly from these thoroughfares. Below, extending to a depth 42 feet (13 m) beneath the sidewalk, and occupying an additional area of 75 by 242 feet (23 m × 74 m) running toward Broadway, were the basements, which contained the engine room, laundries, and kitchens. From the sidewalk to the observatory roof was a height of 250 feet (76 m).[31] It was the largest hotel in the world at the time.[32][33] The cost of the two buildings, exclusive of the furnishings but including the land, was about $15 million ($473 million in 2023[22]).[34] The assessed value in 1897 was $12.125 million ($382 million in 2023[22]) making it the next most valuable parcel on Fifth Avenue, after the B. Altman and Company Building site immediately northeast.[35] The hotel became, according to author Sean Dennis Cashman, "a successful symbol of the opulence and achievement of the Astor family".[36]

The hotel faced stiff competition from the early 20th century, with a range of new hotels springing up in New York City such as the Hotel Astor (1904), perceived as a successor to the Waldorf-Astoria; The St. Regis (1904), built by John Jacob Astor IV as a companion to the Waldorf-Astoria; The Knickerbocker (1906); and the Savoy-Plaza Hotel (1927).[37] By the 1920s, the hotel was becoming dated, and the elegant social life of New York had moved much farther north than 34th Street. The Astor family sold the hotel to the developers of the Empire State Building and closed the hotel on May 3, 1929; it was demolished soon afterward.[26] The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel records of 1893–1929 are held by the New York Public Library's Archives & Manuscripts division.[38]

Society

[edit]From its inception, the Waldorf was always a "must stay" hotel for foreign dignitaries. The viceroy of China, Li Hung-Chang stayed at the hotel in 1896 and feasted on 100-year-old eggs which he brought with him.[39] Li also brought his own stoves, chefs and servants with him to prepare and serve his meals. Upon his departure from the Waldorf, he ordered a basket of roses to be sent to every female guest at the hotel, and was very generous in the gifts and gratuities he provided for the hotel's staff.[40] In 1902, a lavish dinner was organized for Prince Henry of Prussia; in addition, the hotel built a private door on its 33rd Street side and installed a private elevator. The staff was also called upon to form a "bucket brigade" for the prince's bath when there was a problem with the plumbing in the royal suite.[41][42] One early wealthy resident was Chicago businessman J. W. Gates who would gamble on stocks on Wall Street and play poker at the hotel. He paid up to $50,000 a year to hire suites at the hotel, where he had his own private entrance and elevator.[43][44] Grand Duchess Viktoria Feodorovna of Russia was invited by Waldorf president Lucius Bloomer to stay at the hotel in the 1920s.[45]

The Waldorf-Astoria gained significant renown for its fundraising dinners and balls, regularly attracting notables of the day such as Andrew Carnegie who became a fixture.[46] Banquets were often held in the ballroom for esteemed figures and international royalty. On February 11, 1899, Oscar of the Waldorf hosted a lavish dinner reception which the New York Herald Tribune cited as the city's costliest dinner at the time. Some $250 ($7,739 in 2023[22]) was spent per guest, with bluepoint oysters, green turtle soup, lobster, ruddy duck and blue raspberries.[47] Two months later, 120 sailors of the cruiser Raleigh were given a banquet, during which the gallery was decorated with silk banners and flags.[48] One article that year claimed that at any one time the hotel had $7 million ($217 million in 2023[22]) worth of valuables locked in the safe, testament to the wealth of its guests.[49] In 1909, banquets, attended by hundreds, were organized for Arctic explorer Frederick Cook in September and Elbert Henry Gary, a founder of US Steel, the following month.[50][51]

The hotel was also influential in advancing the status of women, who were admitted singly without escorts. Boldt's wife, Louise, was influential in evolving the idea of the grand urban hotel as a social center, particularly in making it appealing to women as a venue for social events, or just to be seen in the Peacock Alley.[39] The combined hotel was the first to do away with a ladies-only parlor and provided women with a place to play billiards and ping-pong. It was the first New York hotel to allocate an entire room for afternoon tea. The teas began in the Waldorf Garden with attendance eventually being so large, both the Empire Room and at times, the Rose Room, had to be opened during the hours of four and six pm to accommodate the number of guests. Men were admitted to the teas only if they were in the company of a woman.[52]

The United States Senate inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic was opened at the hotel on April 19, 1912, and continued there for some time in the Myrtle Room,[53] before moving on to Washington, D.C.[54] John Jacob Astor IV was one of the people who perished on its ill-fated journey.

The Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra included several conductors over the years. In the early 1900s, it was under the direction of Carlo Curti,[55] who spent his career between the United States and Mexico. Later he was replaced by Joseph Knecht, who was formerly assistant concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera House. Consisting of fifty musicians, it was maintained by Boldt at an annual expense of $100,000. The orchestra performed regular Sunday night concerts in the grand ballroom.[56]

The Waldorf-Astoria Bar was a favorite haunt of many of the financial elite of the city from the hotel's inception in 1893, and colorful characters who adopted the venue such as Diamond Jim Brady, Buffalo Bill Cody and Bat Masterson.[57] A number of cocktails were invented at the bar, including the Rob Roy (1894) and the Bobbie Burns.[58][g]

Architecture

[edit]On the exterior, the two and three lower stories in the respective buildings were of red sandstone, while the balance of the work to the roof-line was red brick and red terracotta. The building rested on solid rock and contained a fireproof steel frame.[34] The first and second floors contained public spaces.[25]

The combined hotel, after merging in 1897, had 1,300 bedrooms and 178 bathrooms, making it the largest hotel in the world at the time.[34][60] With a telephone in every room and first-class room service, the hotel featured numerous Turkish and Russian baths for the gentlemen of the day to relax in.[58][60] Many of the floors were arranged as separate hotels to further the comfort of the guests. Each of these floors had its own team of assistants—clerks, maids, page boys, waiters—as well as telephone and dumbwaiter service, and refrigerators.[61] The bedrooms and corridors were heated by direct radiation.[34] The family included a stained glass picture of the town of Walldorf in the design of the hotel; it was located on the 33rd Street side over the main entrance to the South Palm Garden.[62]

Waldorf Hotel

[edit]The Waldorf Hotel, built at a reported cost of about $5 million ($152 million in 2023[22]), opened on March 13, 1893, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, on the site where millionaire developer William Waldorf Astor had previously built his mansion.[4][26] The hotel stood 225 feet (69 m) high, about 50 feet (15 m) lower than the Astoria, with a frontage of about 100 feet (30 m) on Fifth Avenue, and a total area of 69,475 square feet (6,454.4 m2).[63] It was a German Renaissance structure, designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, with 15 public rooms and 450 guest rooms, and a further 100 rooms allocated to servants, with laundry facilities on the upper floors.[64][65] The New York Times proclaimed the hotel a palace after it opened in 1893.[66]

The exterior featured loggias, balconies, gables, groups of chimneys, and tiled roofs.[67] One of the chief features was the interior garden court, with fountains and flowers, walls of white terracotta, frescoes and stained glass. The main entrance to the hotel was "sheltered by an elaborate frosted-glass-and-wrought-iron marquee", and the entrance hall was built in Sienna marble, with a mosaic title floor and a coffered ceiling.[65] The original reception desk of the Waldorf Hotel became a registration desk when it merged with the Astoria Hotel in 1897.[65]

Beyond the lobby was the main corridor leading to the Empire Room, with an alcove containing elevators and a grand staircase. Near this was the Marie Antoinette parlor, which was used as a reception room for women. It contained 18th century antiques brought back by Boldt and his wife from an 1892 visit to Europe, including a bust of Marie Antoinette, and an antique clock which was once owned by the queen. The ceiling featured frescoes by Will Hicok Low, the central of which was called The Birth of Venus.[68] The Gentleman's Cafe was furnished with "robust black oak paneling, hunting murals, and stag-horn chandaliers".[69]

The Empire Room was the largest and most lavishly adorned room in the Waldorf, and soon after opening it became one of the best restaurants in New York City, rivaling Delmonico's and Sherry's.[70] It was modelled after the grand salon in King Ludwig's palace at Munich, with satin hangings, upholstery and marble pillars, all of pale green, and Crowninshield's frescoes.[71] Empire in style, the Waldorf's restaurant featured feathered columns of dark-green marble, and the pilasters that were opposite were of mahogany, with ormolu work in the panels.[34] The caps and bases of both columns and pilasters were gilded. This treatment occupied most of the wall space. The ceiling was divided by heavy beams running from column to column, and between these the flat space was divided into oval and other shaped panels with light mouldings.[34] The color scheme was in tints of pale-green and cream. The panels of the ceiling were frescoed with figures in pinkish-red on a blue sky or field. The walls were principally mahogany and gold, with a little color in the comparatively small wall-spaces left between openings.[72] Among the other rooms were the Turkish smoking room, with low divans and ancient Moorish armor, and the ballroom, in white and gold, with Louis XIV decorations.[64]

The Waldorf State Apartments, consisting of nine suites, were located on the second floor. The apartments, including the Henry IV Drawing Room, featured 16th and 17th century French and Italian antiques which Boldt and his wife had brought back from Europe.[72] Francois V Bedroom was a reproduction of the room at the Palais de Fontainebleau, and over the years was occupied by the likes of Li Hung-Chang of China, Chowfa Maha Rajiravuth, Prince of Siam, and Albert of Saxe-Coburg.[73] The apartments had their own music room and a banquet hall to seat 20, with a handsome china collection including 48 Sevres plates with European portraits.[74] There were about 6,000 lights in the hotel, with as many as 1,000 small candelabra lamps mounted in specially designed fixtures.[75] The electric fixtures were all furnished by the Archer & Pancoast Manufacturing Company, of New York, while the contract for the general installation work was carried out by the Edison Electric Illuminating Company, of New York, the actual work of wiring being done by the Eastern District of the General Electric Company. The building was wired throughout on the system of the Interior Conduit and Insulation Company.[75]

Astoria Hotel

[edit]The Astoria Hotel, opened in 1897, was situated on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. Like the Waldorf, it was designed in the German Renaissance style by Henry J. Hardenbergh, the same architect who designed the Waldorf.[26][67] With dimensions of 99 by 350 feet (30 m × 107 m), its height, from the floor of the sub-basement, which was 33 feet (10 m) below the street level, to the roof-line, was about 270 feet (82 m), or about 240 feet (73 m) above the street-level. It was 16 stories in height, including the four stories in the roof.[34] The building was constructed of stone, marble and brick, with a steel skeleton frame and modern fireproof interior construction, and was embellished with "French Second Empire Mansard-roofed towers with iron-work cresting as well as Austrian Baroque onion-domes over corners turrets".[60][67] There were 25 public rooms and 550 guest rooms, with miles of corridors, vestibules and balls.[67] The entrance featured a double set of plate glass doors to give protection in cold weather, and a U-shaped driveway for horse and carriages.[76]

The main corridor was nicknamed "Peacock Alley" by the New York press.[77] The corridor and foyer were treated with pilasters and columns of Sienna marble and a color scheme on the walls and ceilings of salmon-pink, with cream-color and pale-green. The capitals of the columns and pilasters were gilded of solid brass or lacquered. The main corridor ran the entire length of the building from east to west.[h] To the left of it was the Astor Dining Room, fronting on Fifth Avenue, which measured 50 by 92 feet (15 m × 28 m). Great care was taken with it to faithfully reproduce the original dining room of the mansion, three floors above where the original dining room had stood,[79] including all of the original dining room's paneling, carpeting, drapery and fireplace mantel; Italian Renaissance pilasters and columns, carved of marble from northern Russia. The panels of silk hangings were of rose pompadour, and a series of Charles Yardley Turner mural paintings filled arches and panels at the south end of the room.[67][i] On the right of the main corridor was the Garden Court of Palms, 88 by 57 feet (27 m × 17 m), rising three stories to a dome-like roof of amber glass 56 feet (17 m) above the floor. This, too, was used as a dining room. It was decorated in the Italian style, finished in gray, terracotta and Pavonazzo marble.[67] On the 34th Street side of the corridor was the cafe, 40 by 95 feet (12 m × 29 m), finished in English oak in the style of the German Renaissance, with Flemish decoration. The bar formed another room 40 by 50 feet (12 m × 15 m).[67]

On the first floor, at the head-of the east main staircase, was the Astor Gallery, 87 by 102 feet (27 m × 31 m), looking out on 34th Street. The gallery, with seven French windows reaching 26 feet (7.9 m) from floor to ceiling, opened onto a terrace over the entrance to the hotel. The interior was finished in the style of the Hôtel de Soubise, with a blue, gray and gold color scheme. There was a parquet floor, and on the south side, opposite the street windows, were other windows which opened into the main corridor on the second floor. The musicians' balcony, upheld by two caryatids, was at the east end. All the balcony railings were of gilded metal work. The mural paintings were notable: four panels, two at either end of the room, and twelve pendentive panels, six on either side and painted by Edward Simmons depicted the four seasons and the twelve months of the year.[67] The "Colonial Room" was decorated in red, contrasting with white woodwork.[34] The second floor contained a private suite of apartments at the northeast corner, with large drawing rooms, dining room, butler's pantry, hallway, three bedrooms, three maids' bedrooms and five bathrooms, all finished in old English oak. All the floors above the third were given up to suites and bedrooms up to the 14th floor. There was a bath for nearly every room, and every bathroom had windows opening to the air, not into shafts. In every room, there was a large trunk closet.[81]

The ballroom, in the Louis XIV style, has been described as the "pièce de résistance" of the hotel, measuring 65 feet (20 m) by 95 feet (29 m) and 40 feet (12 m) (three stories) in height.[60] It had a capacity to seat 700 at banquets and 1,200 at concerts, and featured tints of ivory-gray and cream in its design.[34] Noted vocalists such as Enrico Caruso and Nellie Melba performed in the ballroom, with conductor Anton Seidl leading a series of concerts there in the year the combined hotels opened for business. It was possible to buy season tickets for the musical offerings; a box for a season was US$350 and a seat for a season on the ballroom floor was priced at US$60.[82]

On the hotel's top floor was the roof-garden, enclosed on all sides by glass, with a glass roof over. It was furnished with rattan chairs and lounges in pale-green and pink, hung across with gauzy fabric.[34] On the roof on the 34th Street side was the grand promenade, 90 by 200 feet (27 m × 61 m), on solid footing high in the air, with a band stand, fountains, and trellises of columns. The roof garden restaurant occupied a space 75 by 84 feet (23 m × 26 m), and was roofed in. The ceiling was 24 feet (7.3 m) high. At the northeast and northwest corners of the roof garden were towers, with spiral stairways within, leading up to the copper covered roofs of the pavilions, which were 250 feet (76 m) above the sidewalk.[67] The palm gardens, used as cafes, rose to a height of two and three stories respectively and were roofed-over with domes of tinted glass. Balconies at the various floor levels opened on to these courts to overlook them. The materials used were cream-colored brick and terracotta, and were Italian Renaissance in style.[34]

In the sub-basement were the Sprague screw machines for the electric elevators, the fire pumps, the house pumps, the ice plant, and the six Babcock & Wilcox water tube boilers. The elevator system, which served the house from subbasement to roof, was electric, taking its power from the generating plant within the building. There were 18 elevators.[67] The machinery was located in the sub-basement. The boilers aggregated about 3,000 horse power, the electric generators taking 2,200 horse-power of the total energy. The elevators were run by it, as were the 15,000 incandescent lamps, branching from 7,500 outlets.[34] The system of heating and ventilating the public rooms was that of forced draught by means of powerful blowers situated in the sub-basement that forced the fresh air between steam-coils, where it became moderately heated before entering the ducts that lead it to the various rooms. This heat was further augmented by direct radiators placed behind screens in the recesses of the windows and elsewhere.[34]

Notable people

[edit]

William Waldorf Astor (1848–1919) was a wealthy American attorney, politician, businessman, and newspaper publisher of the Astor family. He was the only child of financier/philanthropist John Jacob Astor III (1822–1890) and Charlotte Augusta Gibbes (1825–1887). Described as being a "very prickly sort of person", he had a background in Europe and earned wealth buying and selling country estates in England including Cliveden and Hever Castle.[83] In his early adult years, Astor returned to the United States and began studies at Columbia Law School. He was called to the United States Bar in 1875.[84] He worked for a short time in law practice and in the management of his father's estate of financial and real estate holdings. On his death in 1919, he was reputed to have been worth £200 million, which he left in trust for his two sons Waldorf and John Jacob. His half share of the Waldorf Astoria and the Astor Hotel at the time were reported to have been worth £10 million.[85]

George Boldt (1851–1916), the founding proprietor, was a Prussian-born American hotelier and self-made millionaire who influenced the development of the urban hotel as a civic social center and luxury destination. His motto was "the guest is always right",[86] and he became a wealthy and prominent figure internationally. The hotel was built to his specifications. He served as president and director of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel Company, as well as the Waldorf-Astoria Segar Company and the Waldorf Importation Company.[87] He also owned and operated the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, an elite boutique hotel on Broad Street in Philadelphia, with his wife, Louise. Boldt was described as "Mild mannered, undignified, unassuming", resembling "a typical German professor with his close-cropped beard which he kept fastidiously trimmed... and his pince-nez glasses on a black silk cord".[23] Boldt retained his contacts with the European elite and he and his wife made frequent trips to Europe, bringing back with them many antiques, a characteristic of the Waldorf Astoria. Boldt continued to own the Bellevue even after his relationship with the Astors blossomed.[86]

Lucius M. Boomer (1878–1947) was an American hotelier and businessman, responsible for the general management of the hotel for many years.[88] Physically impressive and brassy, he displayed total dedication to his job and great discipline and care towards his staff, becoming one of the most famous hoteliers of his time.[88] Boomer became interested in the hotel after the death of Boldt in 1916 and purchased it, before buying the Bellevue-Stratford two years later. Following the retirement of Louis Sherry in 1920, he became directing head of the Louis Sherry Ice Cream and Chocolate Company, and was later president of restaurant chain Savarin, Inc.[89] Boomer was primarily responsible for the decision to demolish the hotel and build the new one on Park Avenue in 1931. He continued to manage the hotel until his death in Norway in July 1947.[89]

Henry J. Hardenbergh (1847–1918) was an American architect who designed both hotels in the German Renaissance style. Apprenticed in New York from 1865 to 1870 under Detlef Lienau, in 1870, opened his own practice there. He obtained his first contracts for three buildings at Rutgers College in New Brunswick, New Jersey—the expansion of Alexander Johnston Hall (1871), designing and building Geology Hall (1872) and the Kirkpatrick Chapel (1873)—through family connections. Hardenbergh designed the Dakota Apartments in 1884, and after building the Waldorf he went on to have an illustrious career as "America's premiere architect of grand hotels", designing the Manhattan Hotel (1896), the Plaza Hotel (1907), the Martinique Hotel (1911) and numerous other hotels in cities such as Boston and Washington, D.C.[76]

Louis Sherry (1855–1926) was an American restaurateur, caterer, confectioner and hotelier during the Gilded Age and early 20th century, who was of considerable renown in the business. His name is typically associated with an upscale brand of candy and ice cream, and The Sherry-Netherland hotel in New York City. In 1919, Sherry announced an "alliance" with the Waldorf-Astoria that involved both his candies and catering services.[90] Although it was not disclosed at that time, at some point ownership of Louis Sherry Inc. was significantly vested in "Boomer-duPont interests", a reference to Lucius M. Boomer, then chairman of the Waldorf-Astoria, and T. Coleman du Pont.[90]

Oscar Tschirky (1866–1950), known as "Oscar of the Waldorf", was a Swiss chef, maître d'hôtel from the hotel's inauguration in 1893 until his retirement in 1943. Tschirky had arrived in the United States from Switzerland ten years prior to applying for the position at the new Waldorf and over the years grew to possess an encyclopedic-like knowledge of cuisine and the special trimmings and preferences that the regular diners desired.[91] He authored The Cookbook by Oscar of The Waldorf (1896), a 900-page book featuring recipes such as Waldorf salad,[91] which remain popular worldwide. James Remington McCarthy wrote in his book Peacock Alley that Oscar gained renown among the general public as an artist who "composed sonatas in soups, symphonies in salads, minuets in sauces, lyrics in entrees".[91] In 1902 Tschirky published Serving a Course Dinner by Oscar of the Waldorf-Astoria, a booklet which explains the intricacies of being a caterer to the American and international elite.[91] Tschirky continued to work for the Waldorf Astoria after the original hotel was demolished until his retirement in 1943.[91]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ During the Revolutionary War, shots rang out on what is now Fifth Avenue from "the battle of the cornfield". Some 3,500 of George Washington's troops were in the city and in danger of being trapped by the British Army. Mary Murray invited the British officers into her home for food and drink. She offered such a repast that General Putnam was able to lead the 3,500 men out of the city and into Harlem heights.[3]

- ^ The feud centered on whether Caroline, the wife of John Jacob Astor III, or William's wife, Mary Dahlgren Paul Astor, would be known in society as "the" Mrs. Astor.[5]

- ^ The Boldts' first two children were born when the couple lived at addresses with the number 13 in them. Boldt himself made important decisions and signed important documents dated on the 13th of the given month.[9]

- ^ After the Waldorf Hotel rose above their home, both Astors threatened to demolish their home and build a stable on the property. Advisers were able to convince John Astor that it would be more sensible to construct a larger hotel on the property instead.[11]

- ^ There were also prominent social families who had come from Baltimore, Boston and Philadelphia for the charity event.[17]

- ^ While Boldt initially faced much public criticism for his rule that Waldorf waiters would be clean-shaven, other hotels adopted the same tenet for their wait staff.[19]

- ^ There was no bar room, per se, at the hotel until the addition of the Astoria. The original plans for the Waldorf did not include one.[59]

- ^ The first Peacock Alley was a corridor in the Waldorf which was the way to the Empire Room and Palm Court. Neither hotel had planned they would be anything more than entries into various public rooms.[78]

- ^ The Astor family requested that their complete dining room be preserved and made part of the hotel. It was dismantled piece by piece and stored until the completion of the hotel. It was then reconstructed there.[80]

Citations

[edit]- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 5.

- ^ Craven 2009, p. 35.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 6, 7.

- ^ a b Morehouse III 1991, p. 20.

- ^ "Astor Families Bury Hatchet". San Francisco, California: San Francisco Chronicle. July 4, 1905. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 13.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 20.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Mock 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Salzman, Joshua A. T. (March 2007). "When the Astors Owned New York: Blue Bloods and Grand Hotels in a Gilded Age (review)". Enterprise and Society. Vol. 8, no. 1. p. 208. doi:10.1093/es/khm011. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ a b McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 23.

- ^ "Waldorf-Astoria to give way to office". Lincoln Evening Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. December 21, 1928. p. 13. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hotel World Known". New York Tribune. New York, New York. February 3, 1918. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 23–28.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 24.

- ^ a b Bishop, Jim (January 26, 1958). "Anger, Spite Tint History of the Waldorf". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Tschirky, Oscar (October 5, 1937). "The Voice of Broadway". The Bee. Danville,Virginia. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tschirky, Oscar (October 5, 1937). "The Voice of Broadway-part 2". The Bee. Danville,Virginia. p. 12. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ a b Seifer 1998, p. 204.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Tauranac 2014, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e "Hotel history". Waldorfnewyork.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 77.

- ^ Biggs 1897, p. 31.

- ^ Biggs 1897, p. 29.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Success Company 1907, p. 14.

- ^ "Guard shot during robbery attempt at Waldorf-Astoria". CNN. October 17, 2004. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ "The Waldorf Astoria". New York Architecture. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m The American Architect and Building News Company 1898, p. 3.

- ^ Biggs 1897, p. 10.

- ^ Cashman 1988, p. 373.

- ^ Blanke 2002, p. 121.

- ^ "Waldorf-Astoria Hotel records 1893-1929". New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Morehouse III 1991, p. 21.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 117–120.

- ^ "All Around The World". Lawrence Daily Journal. Lawrence, Kansas. March 3, 1902. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "World's Host". Altoona Tribune. Altoona, Pennsylvania. September 19, 1936. p. 17. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 22.

- ^ "Stories Told Of the Life of John W. Gates". Parsons, Kansas: The Parsons Daily Sun. September 29, 1911. p. 5. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Nasaw 2007, p. 841.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 32.

- ^ "Sailor Honored". Kansas City Journal. Kansas City, Missouri. April 25, 1899. p. 6. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "High Life in Gotham". Indiana Weekly Messenger. Indiana, Pennsylvania. September 20, 1899. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Banquet in honor of Frederick A. Cook, M.D., by the Arctic Club of America, Sept. 23, 1909, Waldorf-Astoria, N.Y." Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "Congratulatory addresses delivered at a complimentary dinner tendered to Judge Elbert H. Gary at the Waldorf-Astoria, New York City, October 15th, 1909". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kuntz & Smith 1998, p. 77.

- ^ "Six Degrees of Titanic". History.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Reynold Weidenaar (1995). Magic music from the Telharmonium. Scarecrow Press. pp. 132. ISBN 9780810826922.

- ^ Campbell 1916, p. 77.

- ^ "Dining". Waldorfnewyork.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Hotel fact sheet" (PDF). New York University School of Professional Studies. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Lashley, Lynch & Morrison 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Success Company 1907, p. 53.

- ^ Boldt, George. The Waldorf-Astoria. unknown. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Morehouse III 1991, p. 132.

- ^ a b King 1893, p. 218.

- ^ a b c Morrison 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Comstock 1898, p. 51.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 15.

- ^ "Frederick Crowninshield1845 - 1918". National Academy Museum. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Morrison 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 22.

- ^ a b Electrical Engineer 1893, p. 591.

- ^ a b Morrison 2014, p. 31.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 53.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 60–64.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 24.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, p. 106.

- ^ Comstock 1898, p. 55.

- ^ McCarthy and Rutherford 1931, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Morrison 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Funk & Wagnalls Standard Encyclopedia of the World's Knowledge. Funk & Wagnalls company. 1912. p. 367. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ Klein 2005, p. 25.

- ^ a b Morehouse III 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Leonard 1908, p. 81.

- ^ a b Morehouse III 1991, p. 40.

- ^ a b "Lucius Boomer, 68, Waldorf Director, is Dead in Norway". The Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, New York. July 26, 1947. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Sherry's To Move May 17; Fifty-Eighth Street Plan Modified by 'Prohibition and Bolshevism'". The New York Times. May 17, 1919. p. 28. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 2007, p. 595.

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: H. M. Biggs' "Preventive Medicine in the City of New York: The Address in Public Medicine Delivered at the 65th Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association, in Montreal, Canada, September, 1897" (1897)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: H. M. Biggs' "Preventive Medicine in the City of New York: The Address in Public Medicine Delivered at the 65th Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association, in Montreal, Canada, September, 1897" (1897) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: The American Architect and Building News Company's "American Architect and Architecture" (1898)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: The American Architect and Building News Company's "American Architect and Architecture" (1898) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: W. T. Comstock's "Architecture and Building" (1898)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: W. T. Comstock's "Architecture and Building" (1898) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: M. King's "Kings Handbook of New York City" (1898)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: M. King's "Kings Handbook of New York City" (1898) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Electrical Engineer's "Electrical Engineer" (1893)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Electrical Engineer's "Electrical Engineer" (1893)

Bibliography

[edit]- The American Architect and Building News Company (1898). American Architect and Architecture. Vol. 59–62 (Public domain ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: The American Architect and Building News Company. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Bernardo, Mark (July 1, 2010). Mad Men's Manhattan: The Insider's Guide. Roaring Forties Press. ISBN 978-0-9843165-7-1.

- Biggs, Hermann Michael (1897). Preventive Medicine in the City of New York: The Address in Public Medicine Delivered at the 65th Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association, in Montreal, Canada, September, 1897. Vol. 9 (Public domain ed.). Health Department.

- Blanke, David (January 1, 2002). The 1910s. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31251-9. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Campbell, Mrs. David Allen (1916). The Musical Monitor (Public domain ed.). Mrs. David Allen Campbell, Publisher. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Cashman, Sean Dennis (1988). America in the Age of the Titans: The Progressive Era and World War I. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1411-9. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Comstock, William T. (1898). Architecture and Building. Vol. 28 (Public domain ed.). New York: W.T. Comstock.

- Craven, Wayne (2009). Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06754-5.

- Electrical Engineer (1893). Electrical Engineer. Vol. XV (Public domain ed.). Electrical Engineer. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- King, Moses (1893). Kings Handbook of New York City (Public domain ed.). M. King. p. 218.

- Klein, Henry H. (December 1, 2005). Dynastic America and Those Who Own It. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59605-671-8. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Kuntz, Tom; Smith, William Alden (March 1, 1998). The Titanic Disaster Hearings. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-02553-3.

- Lashley, Conrad; Lynch, Paul; Morrison, Alison J. (2007). Hospitality: A Social Lens. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045093-3. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Leonard, John W. (1908). Who's who in Pennsylvania: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries (Public domain ed.). L. R. Hammersly. p. 81.

- McCarthy, James Remington; Rutherford, John (1931). Peacock alley : the romance of the Waldorf-Astoria. Harper. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002634015.

- Mock, Carlos T. (2007). Papi Chulo: A Legend, a Novel, and the Puerto Rican Identity. Floricanto Press. ISBN 978-0-9796457-0-9.

- Morehouse III, Ward (1991). The Waldorf Astoria: America's Gilded Dream. Xlibris, Corp. ISBN 978-1413465044.[self-published source]

- Morrison, William Alan (April 14, 2014). Waldorf Astoria. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2128-6. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Nasaw, David (October 30, 2007). Andrew Carnegie. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-20179-4. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Seifer, Marc (May 1, 1998). Wizard: The Life And Times Of Nikola Tesla: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla. Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-3556-2. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Smith, Andrew F. (May 1, 2007). The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Success Company (1907). Success Magazine and the National Post (Public domain ed.). Success Company. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Tauranac, John (March 21, 2014). The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7109-4. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Waldorf-Astoria (1893-1929) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Waldorf-Astoria (1893-1929) at Wikimedia Commons

- Waldorf Astoria New York

- 1893 establishments in New York (state)

- Hotels established in 1893

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1929

- Astor family

- Defunct hotels in Manhattan

- Fifth Avenue

- Midtown Manhattan

- 1929 disestablishments in New York (state)

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manhattan

- Demolished hotels in New York City

- 34th Street (Manhattan)

- Upper class culture in New York City