William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison | |

|---|---|

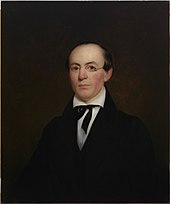

Garrison, c. 1870 | |

| Born | December 10, 1805 |

| Died | May 24, 1879 (aged 73) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Abolitionist, journalist |

| Known for | Editing The Liberator |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Helen Eliza Benson Garrison

(m. 1834; died 1876) |

| Children | 5 |

| Signature | |

William Lloyd Garrison (December 10, 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, which Garrison founded in 1831 and published in Boston until slavery in the United States was partially abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Garrison promoted "no-governmentism" and rejected the inherent validity of the American government on the basis that its engagement in war, imperialism, and slavery made it corrupt and tyrannical. He initially opposed violence as a principle and advocated for Christian pacifism against evil; at the outbreak of the American Civil War, he abandoned his previous principles and embraced the armed struggle and the Lincoln administration. He was one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society and promoted immediate and uncompensated, as opposed to gradual and compensated, emancipation of slaves in the United States.

Garrison was a typesetter, which aided him in running The Liberator, and when working on his own editorials for the paper, Garrison would set them in type without first writing them out on paper.[1]: 57

Much like the martyred Elijah Lovejoy, a price was on Garrison's head; he was burned in effigy and gallows were erected in front of his Boston office. Later on, Garrison would emerge as a leading advocate of women's rights, which prompted a split in the abolitionist community. In the 1870s, Garrison became a prominent voice for the women's suffrage movement.

Early life

[edit]

Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts,[2] the son of immigrants from the British colony of New Brunswick, in present-day Canada. Under An Act for the relief of sick and disabled seamen, his father Abijah Garrison, a merchant-sailing pilot and master, had obtained American papers and moved his family to Newburyport in 1806. The U.S. Embargo Act of 1807, intended to injure Great Britain, caused a decline in American commercial shipping. The elder Garrison became unemployed and deserted the family in 1808. Garrison's mother was Frances Maria Lloyd, reported to have been tall, charming, and of a strong religious character. She started referring to their son William as Lloyd, his middle name, to preserve her family name; he later printed his name as "Wm. Lloyd". She died in 1823, in the city of Baltimore, Maryland.[3]

Garrison sold homemade lemonade and candy as a youth, and also delivered wood to help support the family. In 1818, at 13, Garrison began working as an apprentice compositor for the Newburyport Herald. He soon began writing articles, often under the pseudonym Aristides. (Aristides was an Athenian statesman and general, nicknamed "the Just".) He could write as he typeset his writing, without the need for paper. His most significant contribution to the paper, during the final year of his apprenticeship, was a severe repudiation of American Writers by John Neal. This started a years-long feud.[4] After his apprenticeship ended, Garrison became the sole owner, editor, and printer of the Newburyport Free Press, acquiring the rights from his friend Isaac Knapp, who had also apprenticed at the Herald. One of their regular contributors was poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier. In this early work as a small-town newspaper writer, Garrison acquired skills he would later use as a nationally known writer, speaker, and newspaper publisher. In 1828, he was appointed editor of the National Philanthropist in Boston, Massachusetts, the first American journal to promote legally-mandated temperance.

He became involved in the anti-slavery movement in the 1820s, and over time he rejected both the American Colonization Society and the gradualist views of most others involved in the movement. Garrison co-founded The Liberator to espouse his abolitionist views, and in 1832 he organized out of its readers the New-England Anti-Slavery Society. This society expanded into the American Anti-Slavery Society, which espoused the position that slavery should be immediately abolished.

Career

[edit]Reformer

[edit]At the age of 25, Garrison joined the anti-slavery movement, later crediting the 1826 book of Presbyterian Reverend John Rankin, Letters on Slavery, for attracting him to the cause.[5] For a brief time, he became associated with the American Colonization Society, an organization that promoted the "resettlement" of free blacks to a territory (now known as Liberia) on the west coast of Africa. Although some members of the society encouraged granting freedom to enslaved people, others considered relocation a means to reduce the number of already free blacks in the United States. Southern members thought reducing the threat of free blacks in society would help preserve the institution of slavery. By late 1829–1830, "Garrison rejected colonization, publicly apologized for his error, and then, as was typical of him, he censured all who were committed to it."[6] He stated that anti-colonialism activist and fellow abolitionist William J. Watkins had influenced his view.[7]

Genius of Universal Emancipation

[edit]

In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the Quaker newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation, published at that time in Baltimore, Maryland. With his experience as a printer and newspaper editor, Garrison changed the layout of the paper and handled other production issues. Lundy was freed to spend more time touring as an anti-slavery speaker. Garrison initially shared Lundy's gradualist views, but while working for the Genius, he became convinced of the need to demand immediate and complete emancipation. Lundy and Garrison continued to work together on the paper despite their differing views. Each signed his editorials.

Garrison introduced "The Black List," a column devoted to printing short reports of "the barbarities of slavery – kidnappings, whippings, murders."[8] For instance, Garrison reported that Francis Todd, a shipper from Garrison's home town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, was involved in the domestic slave trade, and that he had recently had slaves shipped from Baltimore to New Orleans in the coastwise trade on his ship the Francis. (This was completely legal. An expanded domestic trade, "breeding" slaves in Maryland and Virginia for shipment south, replaced the importation of African slaves, prohibited in 1808; see Slavery in the United States#Slave trade.)

Todd filed a suit for libel in Maryland against both Garrison and Lundy; he thought to gain support from pro-slavery courts. The state of Maryland also brought criminal charges[clarification needed] against Garrison, quickly finding him guilty and ordering him to pay a fine of $50 and court costs. (Charges against Lundy were dropped because he had been traveling when the story was printed.) Garrison refused to pay the fine and was sentenced to a jail term of six months.[9] He was released after seven weeks when the anti-slavery philanthropist Arthur Tappan paid his fine. Garrison decided to leave Maryland, and he and Lundy amicably parted ways.

The Liberator

[edit]In 1831, Garrison, fully aware of the press as a means to bring about political change,[10]: 750 returned to New England, where he co-founded a weekly anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, with his friend Isaac Knapp.[11] In the first issue, Garrison stated:

In Park-Street Church, on the Fourth of July, 1829, I unreflectingly assented to the popular but pernicious doctrine of gradual abolition. I seize this moment to make a full and unequivocal recantation, and thus publicly to ask pardon of my God, of my country, and of my brethren the poor slaves, for having uttered a sentiment so full of timidity, injustice, and absurdity. A similar recantation, from my pen, was published in the Genius of Universal Emancipation at Baltimore, in September 1829. My conscience is now satisfied. I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; – but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest – I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – and I will be heard. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal and to hasten the resurrection of the dead.[12]

Paid subscriptions to The Liberator were always fewer than its circulation. In 1834 it had two thousand subscribers, three-fourths of whom were black people. Benefactors paid to have the newspaper distributed free of charge to state legislators, governor's mansions, Congress, and the White House. Although Garrison rejected violence as a means for ending slavery, his critics saw him as a dangerous fanatic because he demanded immediate and total emancipation, without compensation to the slave owners. Nat Turner's slave rebellion in Virginia just seven months after The Liberator started publication fueled the outcry against Garrison in the South. A North Carolina grand jury indicted him for distributing incendiary material, and the Georgia Legislature offered a $5,000 reward (equivalent to $152,600 in 2023) for his capture and conveyance to the state for trial.[13]

Knapp parted from The Liberator in 1840. Later in 1845, when Garrison published a eulogy for his former partner and friend, he revealed that Knapp "was led by adversity and business mismanagement, to put the cup of intoxication to his lips,"[14] forcing the co-authors to part.

Among the anti-slavery essays and poems which Garrison published in The Liberator was an article in 1856 by a 14-year-old Anna Elizabeth Dickinson. The Liberator gradually gained a large following in the Northern states. It printed or reprinted many reports, letters, and news stories, serving as a type of community bulletin board for the abolition movement. By 1861 it had subscribers across the North, as well as in England, Scotland, and Canada. After the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment, Garrison published the last issue (number 1,820) on December 29, 1865, writing a "Valedictory" column. After reviewing his long career in journalism and the cause of abolitionism, he wrote:

The object for which the Liberator was commenced – the extermination of chattel slavery – having been gloriously consummated, it seems to be especially appropriate to let its existence cover the historic period of the great struggle; leaving what remains to be done to complete the work of emancipation to other instrumentalities, (of which I hope to avail myself,) under new auspices, with more abundant means, and with millions instead of hundreds for allies.[15]

Garrison and Knapp, printers and publishers

[edit]Organization and reaction

[edit]In addition to publishing The Liberator, Garrison spearheaded the organization of a new movement to demand the total abolition of slavery in the United States. By January 1832, he had attracted enough followers to organize the New-England Anti-Slavery Society which, by the following summer, had dozens of affiliates and several thousand members. In December 1833, abolitionists from ten states founded the American Anti-Slavery Society (AAS). Although the New England society reorganized in 1835 as the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, enabling state societies to form in the other New England states, it remained the hub of anti-slavery agitation throughout the antebellum period. Many affiliates were organized by women who responded to Garrison's appeals for women to take an active part in the abolition movement. The largest of these was the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, which raised funds to support The Liberator, publish anti-slavery pamphlets, and conduct anti-slavery petition drives.

The purpose of the American Anti-Slavery Society was the conversion of all Americans to the philosophy that "Slaveholding is a heinous crime in the sight of God" and that "duty, safety, and best interests of all concerned, require its immediate abandonment without expatriation."[16]

Meanwhile, on September 4, 1834, Garrison married Helen Eliza Benson (1811–1876), the daughter of a retired abolitionist merchant. The couple had five sons and two daughters, of whom a son and a daughter died as children.

The threat posed by anti-slavery organizations and their activity drew violent reactions from slave interests in both the Southern and Northern states, with mobs breaking up anti-slavery meetings, assaulting lecturers, ransacking anti-slavery offices, burning postal sacks of anti-slavery pamphlets, and destroying anti-slavery presses. Healthy bounties were offered in Southern states for the capture of Garrison, "dead or alive".[17]

On October 21, 1835, "an assemblage of fifteen hundred or two thousand highly respectable gentlemen", as they were described in the Boston Commercial Gazette, surrounded the building housing Boston's anti-slavery offices, where Garrison had agreed to address a meeting of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society after the fiery British abolitionist George Thompson was unable to keep his engagement with them. Mayor Theodore Lyman persuaded the women to leave the building, but when the mob learned that Thompson was not within, they began yelling for Garrison. Lyman was a staunch anti-abolitionist but wanted to avoid bloodshed and suggested Garrison escape by a back window while Lyman told the crowd Garrison was gone.[18] The mob spotted and apprehended Garrison, tied a rope around his waist, and pulled him through the streets towards Boston Common, calling for tar and feathers. The mayor intervened and Garrison was taken to the Leverett Street Jail for protection.[19]

Gallows were erected in front of his house, and he was burned in effigy.[20]

The woman question and division

[edit]

Garrison's appeal for women's mass petitioning against slavery sparked controversy over women's right to a political voice. In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs. That summer, sisters Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké responded to the controversy aroused by their public speaking with treatises on woman's rights – Angelina's "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher"[21] and Sarah's "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman"[22] – and Garrison published them first in The Liberator and then in book form. Instead of surrendering to appeals for him to retreat on the "woman question," Garrison announced in December 1837 that The Liberator would support "the rights of woman to their utmost extent." The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society appointed women to leadership positions and hired Abby Kelley as the first of several female field agents.

In 1840, Garrison's promotion of woman's rights within the anti-slavery movement was one of the issues that caused some abolitionists, including New York brothers Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, to leave the AAS and form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which did not admit women. In June of that same year, when the World Anti-Slavery Convention meeting in London refused to seat America's women delegates, Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond, Nathaniel P. Rogers, and William Adams[23] refused to take their seats as delegates as well and joined the women in the spectators' gallery. The controversy introduced the woman's rights question not only to England but also to future woman's rights leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who attended the convention as a spectator, accompanying her delegate-husband, Henry B. Stanton.

Although Henry Stanton had cooperated in the Tappans' failed attempt to wrest leadership of the AAS from Garrison, he was part of another group of abolitionists unhappy with Garrison's influence – those who disagreed with Garrison's insistence that because the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, abolitionists should not participate in politics and government. A growing number of abolitionists, including Stanton, Gerrit Smith, Charles Turner Torrey, and Amos A. Phelps, wanted to form an anti-slavery political party and seek a political solution to slavery. They withdrew from the AAS in 1840, formed the Liberty Party, and nominated James G. Birney for president. By the end of 1840, Garrison announced the formation of a third new organization, the Friends of Universal Reform, with sponsors and founding members including prominent reformers Maria Chapman, Abby Kelley Foster, Oliver Johnson, and Amos Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott).[citation needed]

Although some members of the Liberty Party supported woman's rights, including women's suffrage, Garrison's Liberator continued to be the leading advocate of woman's rights throughout the 1840s, publishing editorials, speeches, legislative reports, and other developments concerning the subject. In February 1849, Garrison's name headed the women's suffrage petition sent to the Massachusetts legislature, the first such petition sent to any American legislature, and he supported the subsequent annual suffrage petition campaigns organized by Lucy Stone and Wendell Phillips. Garrison took a leading role in the May 30, 1850, meeting that called the first National Woman's Rights Convention, saying in his address to that meeting that the new movement should make securing the ballot to women its primary goal.[24] At the national convention held in Worcester the following October, Garrison was appointed to the National Woman's Rights Central Committee, which served as the movement's executive committee, charged with carrying out programs adopted by the conventions, raising funds, printing proceedings and tracts, and organizing annual conventions.[25]

Controversy

[edit]In 1849, Garrison became involved in one of Boston's most notable trials of the time. Washington Goode, a black seaman, had been sentenced to death for the murder of a fellow black mariner, Thomas Harding. In The Liberator Garrison argued that the verdict relied on "circumstantial evidence of the most flimsy character ..." and feared that the determination of the government to uphold its decision to execute Goode was based on race. As all other death sentences since 1836 in Boston had been commuted, Garrison concluded that Goode would be the last person executed in Boston for a capital offense writing, "Let it not be said that the last man Massachusetts bore to hang was a colored man!"[26] Despite the efforts of Garrison and many other prominent figures of the time, Goode was hanged on May 25, 1849.

Garrison became famous as one of the most articulate, as well as most radical, opponents of slavery. His approach to emancipation stressed "moral suasion," non-violence, and passive resistance. While some other abolitionists of the time favored gradual emancipation, Garrison argued for the "immediate and complete emancipation of all slaves." On July 4, 1854, he publicly burned a copy of the Constitution, condemning it as "a Covenant with Death, an Agreement with Hell," referring to the compromise that had written slavery into the Constitution.[27]

In 1855, his eight-year alliance with Frederick Douglass disintegrated when Douglass converted to classical liberal legal theorist and abolitionist Lysander Spooner's view (dominant among political abolitionists) that the Constitution could be interpreted as being anti-slavery.[28]

The events in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, followed by Brown's trial and execution, were closely followed in The Liberator. Garrison had Brown's last speech, in court, printed as a broadside, available in the Liberator office.

Garrison's outspoken anti-slavery views repeatedly put him in danger. Besides his imprisonment in Baltimore and the price placed on his head by the state of Georgia, he was the object of vituperation and frequent death threats.[29] On the eve of the Civil War, a sermon preached in a Universalist chapel in Brooklyn, New York, denounced "the bloodthirsty sentiments of Garrison and his school; and did not wonder that the feeling of the South was exasperated, taking as they did, the insane and bloody ravings of the Garrisonian traitors for the fairly expressed opinions of the North."[30]

After abolition

[edit]

After the United States abolished slavery, Garrison announced in May 1865 that he would resign the presidency of the American Anti-Slavery Society and offered a resolution declaring victory in the struggle against slavery and dissolving the society. The resolution prompted a sharp debate, however, led by his long-time friend Wendell Phillips, who argued that the mission of the AAS was not fully completed until black Southerners gained full political and civil equality. Garrison maintained that while complete civil equality was vitally important, the special task of the AAS was at an end, and that the new task would best be handled by new organizations and new leadership. With his long-time allies deeply divided, however, he was unable to muster the support he needed to carry the resolution, and it was defeated 118–48. Declaring that his "vocation as an Abolitionist, thank God, has ended," Garrison resigned the presidency and declined an appeal to continue. Returning home to Boston, he withdrew completely from the AAS and ended publication of The Liberator at the end of 1865. With Wendell Phillips at its head, the AAS continued to operate for five more years, until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution granted voting rights to black men. (According to Henry Mayer, Garrison was hurt by the rejection, and remained peeved for years; "as the cycle came around, always managed to tell someone that he was not going to the next set of [AAS] meetings" [594].)[citation needed]

After his withdrawal from AAS and ending The Liberator, Garrison continued to participate in public reform movements. He supported the causes of civil rights for blacks and woman's rights, particularly the campaign for suffrage. He contributed columns on Reconstruction and civil rights for The Independent and The Boston Journal.[citation needed]

In 1870, he became an associate editor of the women's suffrage newspaper, the Woman's Journal, along with Mary Livermore, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Lucy Stone, and Henry B. Blackwell. He served as president of both the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. He was a major figure in New England's woman suffrage campaigns during the 1870s.[31]

In 1873, he healed his long estrangements from Frederick Douglass and Wendell Phillips, affectionately reuniting with them on the platform at an AWSA rally organized by Abby Kelly Foster and Lucy Stone on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Boston Tea Party.[32] When Charles Sumner died in 1874, some Republicans suggested Garrison as a possible successor to his Senate seat; Garrison declined on grounds of his moral opposition to taking office.[33]

Antisemitism

[edit]Garrison called the ancient Jews an exclusivist people "whose feet ran to evil" and suggested that the Jewish diaspora was the result of their own "egotism and self-complacency."[34][35] When the Jewish-American sheriff and writer Mordecai Manuel Noah defended slavery, Garrison attacked Noah as "the miscreant Jew" and "the enemy of Christ and liberty." On other occasions, Garrison described Noah as a "Shylock" and as "the lineal descendant of the monsters who nailed Jesus to the cross."[36][37]

However, Garrison acknowledged prejudice against Jews in Europe, which he compared to prejudice against African-Americans, and opposed a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States affirming the divinity of Jesus Christ on the basis of religious freedom, writing that "no one can fail to see that the Jew, Unitarian, or Deist could not worship in his own way, as an American citizen, precisely because the Constitution, under which his citizenship exists, would make faith in the New Testament and the divinity of Jesus Christ a national creed."[38]

Later life and death

[edit]

Garrison spent more time at home with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his increasingly ill wife, Helen. She had suffered a small stroke on December 30, 1863, and was increasingly confined to the house. Helen died on January 25, 1876, after a severe cold worsened into pneumonia. A quiet funeral was held in the Garrison home. Garrison, overcome with grief and confined to his bedroom with a fever and severe bronchitis, was unable to join the service. Wendell Phillips gave a eulogy and many of Garrison's old abolitionist friends joined him upstairs to offer their private condolences.[citation needed]

Garrison recovered slowly from the loss of his wife and began to attend Spiritualist circles in the hope of communicating with Helen.[39] Garrison last visited England in 1877, where he met with George Thompson and other longtime friends from the British abolitionist movement.[40]

Suffering from kidney disease, Garrison continued to weaken during April 1879. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition worsened, and his five surviving children rushed to join him. Fanny asked if he would enjoy singing some hymns. Although he was unable to sing, his children sang favorite hymns while he beat time with his hands and feet. On May 24, 1879, Garrison lost consciousness and died just before midnight.[41]

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood on May 28, 1879. At the public memorial service, eulogies were given by Theodore Dwight Weld and Wendell Phillips. Eight abolitionist friends, both white and black, served as his pallbearers. Flags were flown at half-staff all across Boston.[42] Frederick Douglass, then employed as a United States Marshal, spoke in memory of Garrison at a memorial service in a church in Washington, D.C., saying, "It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result."[43]

Garrison's namesake son, William Lloyd Garrison Jr. (1838–1909), was a prominent advocate of the single tax, free trade, women's suffrage, and of the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. His third son, Wendell Phillips Garrison (1840–1907), was literary editor of The Nation from 1865 to 1906. Two other sons (George Thompson Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, his biographer and named after abolitionist Francis Jackson) and a daughter, Helen Frances Garrison (who married Henry Villard), survived him. Fanny's son Oswald Garrison Villard became a prominent journalist, a founding member of the NAACP, and wrote an important biography of the abolitionist John Brown.

Legacy

[edit]

Leo Tolstoy was greatly influenced by the works of Garrison and his contemporary Adin Ballou, as their writings on Christian anarchism aligned with Tolstoy's burgeoning theo-political ideology. Along with Tolstoy publishing a short biography of Garrison in 1904, he frequently cited Garrison and his works in his non-fiction texts like The Kingdom of God Is Within You. In a 2018 publication, American philosopher and anarchist Crispin Sartwell wrote that the works by Garrison and his other Christian anarchist contemporaries like Ballou directly influenced Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., as well.[44]

Memorials

[edit]- Boston installed a memorial to Garrison on the mall of Commonwealth Avenue.

- In 2005 Garrison was inducted into the National Abolition Hall of Fame, in Peterboro, New York.

- In December 2005, to honor Garrison's 200th birthday, his descendants gathered in Boston for the first family reunion in about a century. They discussed the legacy and influence of their most notable family member.

- A shared-use path along the John Greenleaf Whittier Bridge and Interstate 95 between Newburyport and Amesbury, Massachusetts, was named in honor of Garrison. The 2-mile trail opened in 2018 after the new bridge was completed.[45]

Works

[edit]Books

[edit]- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1832). Thoughts on African Colonization; or an Impartial Exhibition of the Doctrines, Principles, and Purposes of the American Colonization Society. Together with the Resolutions, Addresses and Remonstrances of the Free People of Color. 236 pp. Boston: Garrison and Knapp.

- Garrison, William Lloyd (1843). Sonnets and other poems. Boston: Oliver Johnson.

- Garrison, William Lloyd (1852). Selections from the Writings and Speeches of William Lloyd Garrison: With an Appendix. Boston: R[obert] F. Wallcut.

Pamphlets

[edit]- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1830). A brief sketch of the trial of William Lloyd Garrison : for an alleged libel on Francis Todd, of Massachusetts. 8 pp. [Baltimore].

- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1831). An address, delivered before the free people of color, in Philadelphia, New-York, and other cities, during the month of June, 1831. 24 pp. (2nd ed.). Boston: Boston, Printed by S. Foster.

- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1832). An Address on the Progress of the Abolition Cause; delivered before the African Abolition Freehold Society of Boston, July 16, 1832. 24 pp. Boston: Garrison and Knapp.

- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1834). A brief sketch of the trial of William Lloyd Garrison, for an alleged libel on Francis Todd, of Newburyport, Mass. 26 pp. Boston: Garrison and Knapp.

- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1838). An Address Delivered in Marlboro Chapel, July 4, 1838. Boston: Isaac Knapp. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008.

- Proceedings of a crowded meeting of the colored population of Boston, assembled the 15th July, 1846, for the purpose of bidding farewell to William Lloyd Garrison, on his departure for England : with his speech on the occasion. Dublin. 1846.

Broadside

[edit]- Garrison, Wm. Lloyd (1830). Proposals for publishing a weekly paper in Washington, D.C. to be entitled the Liberator, and journal of the times. Baltimore?. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2021. Archived October 23, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Brown, John (1859). Address of John Brown to the Virginia Court, when about to receive the Sentence of Death, for his heroic attempt at Harper's Ferry, to give deliverence to the captives, and to let the oppressed go free. Boston: Wm. Lloyd Garrison.

Newspapers

[edit]- Address at Park Street Church, Boston, July 4, 1829 (Garrison's first major public statement; an extensive statement of egalitarian principle).

- "Address to the Colonization Society" (a slightly abridged version of the address July 4, 1829).

- The Liberator, January 1, 1831 – December 29, 1865 Archived January 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- To the Public (Garrison's introductory column for The Liberator, – January 1, 1831).

- Truisms Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, January 8, 1831).

- The Insurrection Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (Garrison's reaction to news of Nat Turner's rebellion, – The Liberator, September 3, 1831).

- On the Constitution and the Union (The Liberator, December 29, 1832).

- Declaration of Sentiments of the Nationale Anti-Slavery Convention Archived April 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, December 14, 1833)

- Declaration of Sentiments of The New England Non-Resistance Society* Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, September 28, 1838).

- Abolition at the Ballot Box Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, June 28, 1839).

- The American Union Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, January 10, 1845).

- No Union With Slaveholders at the Wayback Machine (archive index)[dead link] (September 24, 1855).

- The Tragedy at Harper's Ferry Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, (The Liberator, October 28, 1859).

- John Brown and the Principle of Nonresistance Archived October 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (Speech in the Tremont Temple, Boston, December 2, 1859, – the day Brown was hanged – The Liberator, December 16, 1859).

- The War – Its Cause and Cure Archived December 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, May 3, 1861).

- Valedictory: The Final Number of The Liberator Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (The Liberator, December 29, 1865).

- The Liberator Files (Horace Seldon's summary of research of Garrison's The Liberator)

- William Lloyd Garrison works (Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection)

- William Lloyd Garrison works (Cornell University Digital Library Collections).

- William Lloyd Garrison on non-resistance : together with a personal sketch by his daughter Fanny Garrison Villard and a tribute by Leo Tolstoy

- Reading Garrison's Letters (Horace Seldon's insight into the thought, work and life of Garrison, – based on "Letters of William Lloyd Garrison", Belknap Press of Harvard University, W. M. Merrill and L. Ruchames Editors).

- Thomas, John L. (1963). The Liberator: William Lloyd Garrison, A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown.

See also

[edit]- Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of women's rights activists

- Boston Vigilance Committee

References

[edit]- ^ Chapman, John Jay (1921). William Lloyd Garrison. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene; Carruth, Gorton (1982). The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0195031865.

- ^ Mayer, 12

- ^ Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD thesis). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. p. 568. OCLC 7588473.

- ^ Hagedorn, p. 58

- ^ Cain, William E. William Lloyd Garrison and the fight against Slavery: Selections from the Liberator.

- ^ "William Watkins MSA SC 5496-002535". msa.maryland.gov. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, 119

- ^ Masur, Louis (2001). 1831, Year of Eclipse (7th ed.). New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0809041183.

- ^ Dinius, Marcy J. (2018). "Press". Early American Studies. 16 (4): 747–755. doi:10.1353/eam.2018.0045. S2CID 246013692. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Boston Directory, 1831, archived from the original on March 27, 2016, retrieved December 11, 2015,

Garrison & Knapp, editors and proprietors Liberator, 10 Merchants Hall, Congress Street

- ^ William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (Inaugural editorial) Archived March 29, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "William Lloyd Garrison". prezi.com. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ "Death of Isaac Knapp". theliberatorfiles.com. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Valedictory (1865-12-29): by William Lloyd Garrison Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. The first part of the column included the following: "Commencing my editorial career when only twenty years of age, I have followed it continuously till I have attained my sixtieth year – first, in connection with The Free Press, in Newburyport, in the spring of 1826; next, with The National Philanthropist, in Boston, in 1827; next, with The Journal of the Times, in Bennington, Vt., in 1828–29; next, with The Genius of Universal Emancipation, in Baltimore, in 1829–30; and, finally, with the Liberator, in Boston, from January 1, 1831, to January 1, 1866 – at the start, probably the youngest member of the editorial fraternity in the land, now, perhaps, the oldest, not in years, but continuous service, – unless Mr. Bryant, of the New York Evening Post, be an exception. ..."

- ^ Quoted in: Clifton E. Olmstead (1960): History of Religion in the United States. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., p. 369

- ^ David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage. The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0195140737, p. 263.

- ^ Mayer, 201–204

- ^ "Boston Gentlemen Riot for Slavery". New England Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Holly (2019). American radicals : how nineteenth-century protest shaped the nation. New York: Crown. pp. 14, 71–72. ISBN 978-0525573098.

- ^ "Letters to Catherine E. Beecher", Knapp (1838), Boston

- ^ "Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and Condition of Woman" Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Knapp (1838), Boston

- ^ Seldon, Horace. "The 'Women's Question' and Garrison". The liberator files. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "Women's Rights Convention," Liberator, June 7, 1850

- ^ Million, Joelle, Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Women's Rights Movement. Praeger, 2003. ISBN 027597877X, pp. 104, 109, 293 note 26.

- ^ Garrison, William Lloyd (March 30, 1849). "Shall He Be Hung?". The Liberator. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Winter 2000). "Garrison's Constitution. The Covenant with Death and How It Was Made". Prologue Magazine. 32 (4).

- ^ Spooner, Lysander (1845). "The Unconstitutionality of Slavery".

- ^ "William L. Garrison". www.ohiohistorycentral.org. Ohio History Central. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 31, 1860, p. 3; the paper pronounced this an "admirable discourse."

- ^ , Merk, Lois Bannister, "Massachusetts and the Woman Suffrage Movement." Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1958, Revised, 1961, pp. 14, 25.

- ^ Mayer, 614

- ^ Mayer, 618

- ^ Michael, Robert; Rosen, Philip (2007). Dictionary of Antisemitism from the Earliest Times to the Present. lanham, Maryland / Toronto / Plymouth, UK: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 173. ISBN 978-0810858626.

- ^ Garrison, William Lloyd; Ruchames, Louis; Merrill, Walter M. (1981). The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison. Edited by Walter M. Merrill and Louis Ruchames. Cambridge, Mass., Belknap press of Harvard university press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-674-52666-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Who cares if Bernie Sanders is Jewish?". WHYY. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "The Powerful Example Of The Jewish Abolitionists We Forgot". The Forward. January 30, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Ruchames, Louis (1952). "The Abolitionists and the Jews". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. 42 (2): 147–148. ISSN 0146-5511. JSTOR 43057515. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

- ^ Mayer, 621

- ^ Mayer, 622

- ^ Mayer, 626

- ^ Mayer, 627–628

- ^ Mayer, 631

- ^ Sartwell, Crispin (January 1, 2018). "Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought". Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy: 454–483. doi:10.1163/9789004356894_018. ISBN 978-9004356887.

- ^ "Garrison Trail opens this afternoon". October 18, 2018. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0195037529.

- Dal Lago, Enrico. William Lloyd Garrison and Giuseppe Mazzini: Abolition, Democracy, and Radical Reform. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

- Grimké, Archibald Henry (1891). William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- Hagedorn, Ann. Beyond The River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0684870657.

- Hummel, Jeff (2008). "Garrison, William Lloyd (1805–1879)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 203–204. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n121. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Mayer, Henry (1998). All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- McDaniel, W. Caleb. The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

- Laurie, Bruce Beyond Garrison. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0521605172.

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2007)

- Stewart, James Brewer (2008). "William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and the Symmetry of Autobiography: Charisma and the Character of Abolitionist Leadership". Abolitionist Politics and the Coming of the Civil War. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 89–109. ISBN 978-1558496354 – via Project MUSE.

- Thomas, John L. The Liberator: William Lloyd Garrison, A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1963. ISBN 1597401854.

External links

[edit]- Works by William Lloyd Garrison at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Lloyd Garrison at the Internet Archive

- Works by William Lloyd Garrison at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- William Lloyd Garrison profile on Spartacus Educational

- The Liberator Files online

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- "William Lloyd Garrison" and "Who is William Lloyd Garrison?" – American Experience, PBS

- "William Lloyd Garrison: Words of Thunder." WGBH Forum

- PBS Teachers Resources: William Lloyd Garrison 1805–1879

- The story of his life is retold in the 1950 radio drama "The Liberators (Part I)", a presentation from Destination Freedom, written by Richard Durham

- 1805 births

- 1879 deaths

- 19th-century American journalists

- 19th-century American male writers

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th century in Boston

- 19th-century Unitarians

- Abolitionists from Boston

- American libertarians

- American male journalists

- American newspaper editors

- American newspaper founders

- American people of Canadian descent

- American social reformers

- American tax resisters

- American Unitarians

- American women's rights activists

- Deaths from kidney disease

- Individualist feminists

- People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War

- Writers from Newburyport, Massachusetts

- American printers

- American book publishers (people)

- American Anti-Slavery Society

- Underground Railroad in New York (state)

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Garrison family