Dixie (song)

| |

Unofficial national anthem of the Confederate States of America | |

| Also known as | Dixie's Land I Wish I Was in Dixie |

|---|---|

| Lyrics | Daniel Decatur Emmett, 1859 |

| Music | Daniel Decatur Emmett, 1859 |

| Audio sample | |

Instrumental version performed by the West Point Band | |

"Dixie", also known as "Dixie's Land", "I Wish I Was in Dixie", and other titles, is a song about the Southern United States first made in 1859. It is one of the most distinctively Southern musical products of the 19th century. It was not a folk song at its creation, but it has since entered the American folk vernacular. The song likely rooted the word "Dixie" in the American vocabulary as a nickname for the Southern U.S.

Most sources credit Ohio-born Daniel Decatur Emmett with the song's composition, although other people have claimed credit, even during Emmett's lifetime. Compounding the problem are Emmett's own confused accounts of its writing and his tardiness in registering its copyright.

"Dixie" originated in the minstrel shows of the 1850s and quickly became popular throughout the United States. During the American Civil War, it was adopted as a de facto national anthem of the Confederacy, along with "The Bonnie Blue Flag" and "God Save the South". New versions appeared at this time that more explicitly tied the song to the events of the Civil War.

The song was a favorite of Kentucky native President Abraham Lincoln, who had it played at some of his political rallies and at the announcement of General Robert E. Lee's surrender.[1][2]

Structure

[edit]"Dixie" is structured into five two-measure groups of alternating verses and refrains, following an AABC pattern.[3] As originally performed, a soloist or small group stepped forward and sang the verses, and the whole company answered at different times; the repeated line "look away" was probably one part sung in unison like this. As the song became popular, the audience likely joined the troupe in singing the chorus.[4] Traditionally, another eight measures of unaccompanied fiddle playing followed, coming to a partial close in the middle; since 1936, this part has rarely been printed with the sheet music.[5]

The song was traditionally played at a tempo slower than the one usually played today. Rhythmically, the music is "characterized by a heavy, nonchalant, inelegant strut,"[6] and is in duple meter, which makes it suitable for both dancing and marching. "Dixie" employs a single rhythmic motive (two sixteenth note pickups followed by a longer note), which is integrated into long, melodic phrases. The melodic content consists primarily of arpeggiations of the tonic triad, firmly establishing the major tonality. The melody of the chorus emulates natural inflections of the voice (particularly on the word "away"), and may account for some of the song's popularity.[7]

According to musicologist Hans Nathan, "Dixie" resembles other material that Dan Emmett wrote for Bryant's Minstrels, and in writing it, the composer drew on a number of earlier works. The first part of the song is anticipated by other Emmett compositions, including "De Wild Goose-Nation" (1844), itself a derivative of "Gumbo Chaff" (1830s) and ultimately an 18th-century English song called "Bow Wow Wow". The second part is possibly related to other material, most likely Scottish folk songs.[8] The chorus follows portions of "Johnny Roach," an Emmett piece from earlier in 1859.[9]

As with other blackface material, performances of "Dixie" were accompanied by dancing. The song is a walkaround, which originally began with a few minstrels acting out the lyrics, only to be joined by the rest of the company (a dozen or so individuals for the Bryants).[10] As shown by the original sheet music (see below), the dance tune used with "Dixie" by Bryant's Minstrels, who introduced the song on the New York stage, was "Albany Beef", an Irish-style reel later included by Dan Emmett in an instructional book he co-authored in 1862.[11][unreliable source][10] Dancers probably performed between verses,[4] and a single dancer used the fiddle solo at the end of the song to "strut, twirl his cane, or mustache, and perhaps slyly wink at a girl on the front row."[12]

Lyrics

[edit]Countless lyrical variants of "Dixie" exist, but the version attributed to Dan Emmett and its variations are the most popular.[4] Emmett's lyrics as they were originally intended reflect the hostile mood of many white Americans in the late 1850s towards increasing abolitionist sentiments in the United States. The song presented the point of view, common to minstrelsy at the time, that slavery in the United States was a positive institution overall. The character of the pining slave had been used in minstrel tunes since the early 1850s, including Emmett's "I Ain't Got Time to Tarry" and "Johnny Roach". The fact that "Dixie" and its precursors were dance tunes only further made light of the subject.[13] In short, "Dixie" made the case, more strongly than any previous minstrel tune had, that African Americans ought to be enslaved.[14] This was accomplished through the song's protagonist, who, speaking in an exaggerated black dialect, implies that despite his freedom, he is homesick for the slave plantation he was born on.[15]

The lyrics use many common phrases found in minstrel tunes of the day—"I wish I was in ..." dates to at least "Clare de Kitchen" (early 1830s), and "Away down south in ..." appears in many more songs, including Emmett's "I'm Gwine ober de Mountain" (1843). The second stanza clearly echoes "Gumbo Chaff" from the 1830s: "Den Missus she did marry Big Bill de weaver / Soon she found out he was a gay deceiver."[16] The final stanza rewords portions of Emmett's own "De Wild Goose-Nation": "De tarapin he thot it was time for to trabble / He screw aron his tail and begin to scratch grabble."[17] Even the phrase "Dixie's land" had been used in Emmett's "Johnny Roach" and "I Ain't Got Time to Tarry," both first performed earlier in 1859.[citation needed]

While "Dixie" evolved and took many forms, with performers frequently adding their own verses or parodic alterations, the chorus largely remained unchanged.[18] Today, the most widely recognized version of "Dixie" is often sung in standard English and focuses on the chorus, which has become emblematic of the song. The first verse and chorus, in their best-known non-dialect form, are as follows:[19]

I wish I was in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten,

Look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land where I was born in, early on a frosty mornin',

Look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land.

Then I wish I was in Dixie, hooray! hooray!

In Dixie Land I'll take my stand to live and die in Dixie,

Away, away, away down South in Dixie,

Away, away, away down South in Dixie.[20]

As with other minstrel material, "Dixie" entered common circulation among blackface performers, and many of them added their own verses or altered the song in other ways. Emmett himself adopted the tune for a pseudo-African American spiritual in the 1870s or 1880s. The chorus changed to:

I wish I was in Dixie

Hooray, Hooray!

In Dixie's land, I'll take my stand to live and die in Dixie!

Away, away, away down South in Dixie!

Away, away, away down South in Dixie!

Both Union and Confederate composers produced war versions of the song during the American Civil War. These variants standardized the spelling and made the song more militant, replacing the slave scenario with specific references to the conflict or to Northern or Southern pride. This Confederate verse by Albert Pike is representative:

Southrons! hear your country call you!

Up! lest worse than death befall you! ...

Hear the Northern thunders mutter! ...

Northern flags in South wind flutter; ...

Send them back your fierce defiance!

Stamp upon the cursed alliance![21]

Compare Frances J. Crosby's Union lyrics:

On! ye patriots to the battle,

Hear Fort Moultrie's cannon rattle!

Then away, then away, then away to the fight!

Go meet those Southern traitors,

With iron will.

And should your courage falter, boys,

Remember Bunker Hill.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The Stars and Stripes forever!

Hurrah! Hurrah! Our Union shall not sever![22]

Other Union variations of the lyrics also existed, one of which is known as the Union Dixie.[23][24] It featured allusions that applied more generally,[24] but failed to catch on with the public.[25]:

Away down south in the land of traitors,

Rattlesnakes and alligators,

Right away, come away, right away, right away.

Where cotton's king and men are chattels,

Union boys will win the battles,

Right away, come away, right away, right away.

Then we'll all go down to Dixie,

Away, away,

Each Dixie boy must understand,

that he must mind his Uncle Sam

Away, away,

And we'll all go down to Dixie.

Away, away,

And we'll all go down to Dixie.[26]

"The New Dixie!: The True 'Dixie' for Northern Singers" takes a different approach, turning the original song on its head:

Then I'm glad I'm not in Dixie

Hooray! Hooray!

In Yankee land I'll take my stand,

Won't live or die in Dixie[27]

Soldiers on both sides wrote endless parody versions of the song. Often these discussed the banalities of camp life: "Pork and cabbage in the pot, / It goes in cold and comes out hot," or, "Vinegar put right on red beet, / It makes them always fit to eat." Others were more nonsensical: "Way down South in the fields of cotton, / Vinegar shoes and paper stockings."[28]

Composition and copyright

[edit]

According to tradition, Ohio-born minstrel show composer Daniel Decatur Emmett wrote "Dixie" around 1859.[29] Over his lifetime, Emmett often recounted the story of its composition, and details vary with each account. For example, in various versions of the story, Emmett said he had written "Dixie" in a few minutes, in a single night, and over a few days.[30] An 1872 edition of the New York Clipper provides one of the earliest accounts, relating that on a Saturday night shortly after Emmett had been taken on as a songwriter for the Bryant's Minstrels, Jerry Bryant told him they would need a new walkaround by the following Monday. By this account, Emmett shut himself inside his New York apartment and wrote the song that Sunday evening.[31] The playbill for Jerry Bryant's Minstrel Show dated Monday, April 4, 1859, lists the first performance of "Dixie's Land" at Mechanics' Hall, New York.[32]

Other details emerge in later accounts. In one, Emmett said that "Suddenly... I jumped up and sat down at the table to work. In less than an hour, I had the first verse and chorus. After that it was easy."[33] In another version, Emmett stared out at the rainy evening and thought, "I wish I was in Dixie." Then, "Like a flash the thought suggested the first line of the walk-around, and a little later the minstrel, fiddle in hand, was working out the melody"[34] (a different story has it that Emmett's wife uttered the famous line).[35] Yet another variant, dated to 1903, further changes the details: "I was standing by the window, gazing out at the drizzly, raw day, and the old circus feeling came over me. I hummed the old refrain, 'I wish I was in Dixie,' and the inspiration struck me. I took my pen and in ten minutes had written the first verses with music. The remaining verses were easy."[36] In his final years, Emmett even said he had written the song years before he had moved to New York.[37] An article in The Washington Post supports this, giving a composition date of 1843.[38]

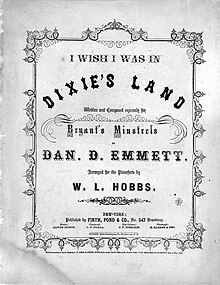

Emmett published "Dixie" (under the title "I Wish I Was in Dixie's Land") on June 21, 1860, through Firth, Pond & Co. in New York. The original manuscript has been lost; extant copies were made during Emmett's retirement, starting in the 1890s. Emmett's tardiness registering the copyright for the song allowed it to proliferate among other minstrel groups and variety show performers. Rival editions and variations multiplied in songbooks, newspapers and broadsides. The earliest of these that is known today is a copyrighted edition for piano from the John Church Company of Cincinnati, published on June 26, 1860. Other publishers attributed completely made-up composers with the song: "Jerry Blossom" and "Dixie, Jr.," among others.[39] The most serious of these challenges during Emmett's lifetime came from Southerner William Shakespeare Hays; this claimant attempted to prove his allegations through a Southern historical society, but he died before they could produce any conclusive evidence.[40] By 1908, four years after Emmett's death, no fewer than 37 people had claimed the song as theirs.[41][42]

"Dixie" is the only song Emmett ever said he had written in a burst of inspiration, and analysis of Emmett's notes and writings shows "a meticulous copyist, [who] spent countless hours collecting and composing songs and sayings for the minstrel stage ... ; little evidence was left for the improvisational moment."[43] The New York Clipper wrote in 1872 that "[Emmett's] claim to authorship of 'Dixie' was and is still disputed, both in and out of the minstrel profession."[44] Emmett himself said, "Show people generally, if not always, have the chance to hear every local song as they pass through the different sections of [the] country, and particularly so with minstrel companies, who are always on the look out for songs and sayings that will answer their business."[45] He claimed at one point to have based the first part of "Dixie" on "Come Philander Let's Be Marchin, Every One for His True Love Searchin", which he described as a "song of his childhood days." Musical analysis does show some similarities in the melodic outline, but the songs are not closely related.[46] Emmett also credited "Dixie" to an old circus song.[37] Despite the disputed authorship, Firth, Pond & Co. paid Emmett $300 for all rights to "Dixie" on February 11, 1861, perhaps fearing complications spurred by the impending Civil War.[47]

The latest[when?] challenge has been made on behalf of the Snowden Family Band of Knox County, Ohio, who may have been the source of Emmett's "Dixie." One strong assertion of the Snowden's claim is the point of view of the original lyrics—not making fun of "darkies," but describing relationships between the mistress of a house and her beau, along with the residents of the "Quarters." This unique point of view reflects the life circumstances of the Snowden family matriarch on her birthplace plantation in Maryland, prior to moving to Ohio.[citation needed]

Origin of the terms "Dixie" and "Dixieland"

[edit]Various theories exist regarding the origin of the term "Dixie". According to Robert LeRoy Ripley (founder of Ripley's Believe It or Not!), "Dixieland" was a farm on Long Island, New York, owned by a man named John Dixie. He befriended so many slaves before the Civil War that his place became a sort of a paradise to them.[full citation needed]

James H. Street says that "Johaan Dixie" was a Haarlem (Manhattan Island) farmer who decided that his slaves were not profitable because they were idle during the New York winter, so he sent them to Charleston where they were sold.[48] Subsequently, the slaves were busy constantly, longing for the less strenuous life on the Haarlem farm; they would chant, "I sure wish we was back on Dixie's land."[citation needed]

One explanation revolves around currency of the period, the ten-dollar note from Banque des Citoyens de la Louisiane (the Citizens Bank of New Orleans, in the French Quarter) which had engraved on the reverse a large DIX (ten, in French, the language of many in New Orleans of the period). The notes were known as Dixies by Southerners, and the area around New Orleans and the French-speaking parts of Louisiana came to be known as Dixieland.[49]

Another popular theory maintains that the term originated in the Mason–Dixon line.[50]

Popularity through the Civil War

[edit]

Bryant's Minstrels premiered "Dixie" in New York City on April 4, 1859, as part of their blackface minstrel show. It appeared second to last on the bill, perhaps an indication of the Bryants' lack of faith that the song could carry the minstrel show's entire finale.[51] The walkaround was billed as a "plantation song and dance."[52] It was a runaway success, and the Bryants quickly made it their standard closing number.

"Dixie" quickly gained wide recognition and status as a minstrel standard, and it helped rekindle interest in plantation material from other troupes, particularly in the third act. It became a favorite of Abraham Lincoln and was played during his campaign in 1860.[53] The New York Clipper wrote that it was "one of the most popular compositions ever produced" and that it had "been sung, whistled, and played in every quarter of the globe."[54] Buckley's Serenaders performed the song in London in late 1860, and by the end of the decade, it had found its way into the repertoire of British sailors.[55] As the American Civil War broke out, one New Yorker wrote,

"Dixie" has become an institution, an irrepressible institution in this section of the country ... As a consequence, whenever "Dixie" is produced, the pen drops from the fingers of the plodding clerk, spectacles from the nose and the paper from the hands of the merchant, the needle from the nimble digits of the maid or matron, and all hands go hobbling, bobbling in time with the magical music of "Dixie."[56]

The Rumsey and Newcomb Minstrels brought "Dixie" to New Orleans in March 1860; the walkaround became the hit of their show. That April, Mrs. John Wood sang "Dixie" in a John Brougham burlesque called Po-ca-hon-tas, or The Gentle Savage, increasing the song's popularity in New Orleans. On the surface "Dixie" seems an unlikely candidate for a Southern hit; it has a Northern composer, stars a black protagonist, is intended as a dance song, and lacks any of the patriotic bluster of most national hymns and marches. Had it not been for the atmosphere of sectionalism in which "Dixie" debuted, it might have faded into obscurity.[57] Nevertheless, the refrain "In Dixie Land I'll took my stand / To lib an die in Dixie", coupled with the first verse and its sanguine picture of the South, hit a chord.[58] Woods's New Orleans audience demanded no fewer than seven encores.[59]

New Orleans publisher P. P. Werlein took advantage and published "Dixie" in New Orleans. He credited music to J. C. Viereck and Newcomb for lyrics. When the minstrel denied authorship, Werlein changed the credit to W. H. Peters. Werlein's version, subtitled "Sung by Mrs. John Wood," was the first "Dixie" to do away with the faux black dialect and misspellings. The publication did not go unnoticed, and Firth Pond & Co. threatened to sue. The date on Werlein's sheet music precedes that of Firth, Pond & Co.'s version, but Emmett later recalled that Werlein had sent him a letter offering to buy the rights for $5.[60] In a New York musical publishers' convention, Firth, Pond & Co. succeeded in convincing those present that Emmett was the composer. In future editions of Werlein's arrangement, Viereck is merely credited as "arranger." Whether ironically or sincerely, Emmett dedicated a sequel called "I'm Going Home to Dixie" to Werlein in 1861.[61]

"Dixie" quickly spread to the rest of the South, enjoying vast popularity. By the end of 1860, secessionists had adopted it as theirs; on December 20 the band played "Dixie" after each vote for secession at St. Andrew's Hall in Charleston, South Carolina.[59] On February 18, 1861, the song took on something of the air of national anthem when it was played at the inauguration of Jefferson Davis, arranged as a quickstep by Herman Frank Arnold,[62] and possibly for the first time as a band arrangement.[63] Emmett himself reportedly told a fellow minstrel that year that "If I had known to what use they were going to put my song, I will be damned if I'd have written it."[64]

In May 1861 Confederate Henry Hotze wrote:

It is marvellous with what wild-fire rapidity this tune "Dixie" has spread over the whole South. Considered as an intolerable nuisance when first the streets re-echoed it from the repertoire of wandering minstrels, it now bids fair to become the musical symbol of a new nationality, and we shall be fortunate if it does not impose its very name on our country.[65]

Southerners who shunned the song's low origins and comedic nature changed the lyrics, usually to focus on Southern pride and the war.[66] Albert Pike's enjoyed the most popularity; the Natchez (Mississippi) Courier published it on May 30, 1861, as "The War Song of Dixie," followed by Werlein, who again credited Viereck for composition. Henry Throop Stanton published another war-themed "Dixie," which he dedicated to "the Boys in Virginia".[21] The defiant "In Dixie Land I'll take my stand / To live and die in Dixie" were the only lines used with any consistency. The tempo also quickened, as the song was a useful quickstep tune. Confederate soldiers, by and large, preferred these war versions to the original minstrel lyrics. "Dixie" was probably the most popular song for Confederate soldiers on the march, in battle, and at camp.[67]

Southerners who rallied to the song proved reluctant to acknowledge a Yankee as its composer. Accordingly, some ascribed it a longer tradition as a folk song. Poet John Hill Hewitt wrote in 1862 that "The homely air of 'Dixie,' of extremely doubtful origin ... [is] generally believed to have sprung from a noble stock of Southern stevedore melodies."[68]

Meanwhile, many Northern abolitionists took offense to the South's appropriation of "Dixie" because it was originally written as a satirical critique of the institution of slavery in the South. Before even the fall of Fort Sumter, Frances J. Crosby published "Dixie for the Union" and "Dixie Unionized." The tune formed part of the repertoire of both Union bands and common troops until 1863. Broadsides circulated with titles like "The Union 'Dixie'" or "The New Dixie, the True 'Dixie' for Northern Singers." Northern "Dixies" disagreed with the Southerners over the institution of slavery and this dispute, at the center of the divisiveness and destructiveness of the American Civil War, played out in the culture of American folk music through the disputes over the meaning of this song.[69] Emmett himself arranged "Dixie" for the military in a book of fife instruction in 1862, and a 1904 work by Charles Burleigh Galbreath claims that Emmett gave his official sanction to Crosby's Union lyrics.[70] At least 39 versions of the song, both vocal and instrumental, were published between 1860 and 1866.[71]

Northerners, Emmett among them, also declared that the "Dixie Land" of the song was actually in the North. One common story, still cited today, claimed that Dixie was a Manhattan slave owner who had sent his slaves south just before New York's 1827 banning of slavery. The stories had little effect; for most Americans, "Dixie" was synonymous with the South.[72]

On April 10, 1865, one day after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee, Lincoln addressed a White House crowd:

I propose now closing up by requesting you play a certain piece of music or a tune. I thought "Dixie" one of the best tunes I ever heard ... I had heard that our adversaries over the way had attempted to appropriate it. I insisted yesterday that we had fairly captured it ... I presented the question to the Attorney-General, and he gave his opinion that it is our lawful prize ... I ask the Band to give us a good turn upon it.[73]

Recordings

[edit]Early recordings of the song include band versions by Issler's Orchestra (c. 1895), Gilmore's Band (1896), and the Edison Grand Concert Band (1896), and a vocal version by George J. Gaskin (1896).[74][75][76]

The Norman Luboff Choir recorded it for the 1956 album Songs of the South. This version was used on numerous sign-ons and sign-offs for Southern US TV and radio stations, including WRAL-TV, WBBR, WQOK and WALT.[citation needed]

"Dixie" reconstructed

[edit]

"Dixie" slowly re-entered Northern repertoires, mostly in private performances.[77] New Yorkers resurrected stories about "Dixie" being a part of Manhattan, thus reclaiming the song for themselves. The New York Weekly wrote, "... no one ever heard of Dixie's land being other than Manhattan Island until recently, when it has been erroneously supposed to refer to the South, from its connection with pathetic negro allegory."[78] In 1888 the publishers of a Boston songbook included "Dixie" as a "patriotic song," and in 1895 the Confederate Veterans' Association suggested a celebration in honor of "Dixie" and Emmett in Washington as a bipartisan tribute. One of the planners noted that:

In this era of peace between the sections ... thousands of people from every portion of the United States will be only too glad to unite with the ex-confederates in the proposed demonstration, and already some of the leading men who fought on the Union side are enthusiastically in favor of carrying out the programme. Dixie is as lively and popular an air today as it ever was, and its reputation is not confined to the American continent ... [W]herever it is played by a big, strong band the auditors cannot help keeping time to the music.[79]

However, "Dixie" was still most strongly associated with the South. Northern singers and writers often used it for parody or as a quotation in other pieces to establish a person or setting as Southern.[77] For example, African Americans Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle quoted "Dixie" in the song "Bandana Days" for their 1921 musical Shuffle Along. In 1905 the United Daughters of the Confederacy mounted a campaign to acknowledge an official Southern version of the song (one that would purge it forever of its African American associations).[80] Although they obtained the support of the United Confederate Veterans and the United Sons of Confederate Veterans, Emmett's death the year before turned sentiments against the project, and the groups were ultimately unsuccessful in having any of the 22 entries universally adopted. The song was played at the dedication of Confederate monuments like Confederate Private Monument in Centennial Park, Nashville, Tennessee, on June 19, 1909.[81]

As African Americans entered minstrelsy, they exploited the song's popularity in the South by playing "Dixie" as they first arrived in a Southern town. According to Tom Fletcher, a black minstrel of the time, it tended to please those who might otherwise be antagonistic to the arrival of a group of black men.[82]

Still, "Dixie" was not rejected outright in the North. An article in the New York Tribune, c. 1908, said that "though 'Dixie' came to be looked upon as characteristically a song of the South, the hearts of the Northern people never grew cold to it. President Lincoln loved it, and to-day it is the most popular song in the country, irrespective of section."[83] As late as 1934, the music journal The Etude asserted that "the sectional sentiment attached to Dixie has been long forgotten; and today it is heard everywhere—North, East, South, West."[84]

"Dixie" had become Emmett's most enduring legacy. In the 1900 census of Knox County, Emmett's occupation is given as "author of Dixie."[85] The band at Emmett's funeral played "Dixie" as he was lowered into his grave. His grave marker, placed 20 years after his death, reads,

Modern interpretations

[edit]Beginning in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans have frequently criticised "Dixie", saying it is a racist relic of the Confederacy and a reminder of decades of white domination and segregation. This position was amplified when white opponents to civil rights began answering songs such as "We Shall Overcome" with the song "Dixie".[86][87]

The earliest of these protests came from students of Southern universities, where "Dixie" was a staple of a number of marching bands.[88] Similar protests have since occurred at the University of Virginia, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Tulane University. In 1968, the President of the University of Miami banned the song from its band's performances.[89]

The debate has since moved beyond student populations. Members of the 75th United States Army Band protested "Dixie" in 1971. In 1989, three black Georgia senators walked out when the Miss Georgia Sweet Potato Queen sang "Dixie" in the Georgia chamber. Some musicologists have challenged the song as racist. For example, Sam Dennison writes that "Today, the performance of 'Dixie' still conjures visions of an unrepentant, militarily recalcitrant South, ready to reassert its aged theories of white supremacy at any moment.... This is why the playing of 'Dixie' still causes hostile reactions."[90]

Supporters consider the song a part of the patriotic American repertoire on a par with "America the Beautiful" and "Yankee Doodle." For example, Chief Justice William Rehnquist regularly included "Dixie" in his annual sing-along for the 4th Circuit Judicial Conference in Virginia. However, its performance prompted some African American lawyers to avoid the event.[91]

Campaigns against "Dixie" and other Confederate symbols have helped create a sense of political ostracism and marginalization among working-class white Southerners.[92] Confederate heritage groups and literature proliferated in the late 1980s and early 1990s in response to criticism of the song.[93] Journalist Clint Johnson calls modern opposition to "Dixie" "an open, not-at-all-secret conspiracy"[94] and an example of political correctness. Johnson believes that modern versions of the song are not racist and simply reinforce that the South "extols family and tradition."[95] Other supporters, such as former State Senator Glenn McConnell of South Carolina, have called the attempts to suppress the song cultural genocide.[96]

In 2016, the Ole Miss athletics department announced the song would no longer be played at athletic events – a tradition that had spanned some seven decades at football games and other sporting events. Ole Miss athletic director at the time Ross Bjork said, "It fits in with where the university has gone in terms of making sure we follow our creed, core values of the athletic department, and that all people feel welcome."[97]

In popular culture

[edit]The song added a new term to the American lexicon: "Whistling 'Dixie'" is a slang expression meaning "[engaging] in unrealistically rosy fantasizing."[98] For example, "Don't just sit there whistling 'Dixie'!" is a reprimand against inaction, and "You ain't just whistling 'Dixie'!" indicates that the addressee is serious about the matter at hand.[citation needed]

Dixie is sampled in the film scores of a great many American feature films, often to signify Confederate troops and the American Civil War. For example, Max Steiner quotes the song in the opening scene of his late 1930s score to Gone with the Wind as a down-beat nostalgic instrumental to set the scene and Ken Burns makes use of instrumental versions in his 1990 Civil War documentary. In 1943, Bing Crosby's film Dixie (a biopic of Dan Emmett) features the song and it formed the centerpiece of the finale. Crosby never recorded the song commercially.[citation needed]

The soundtracks of cartoons featuring Southern characters like Foghorn Leghorn often play "Dixie" to quickly set the scene. On the television series The Dukes of Hazzard, which takes place in a fictional county in Georgia, the musical car horn of the General Lee plays the initial twelve notes of the melody from the song. Sacks and Sacks argue that such apparently innocent associations only further serve to tie "Dixie" to its blackface origins, as these comedic programs are, like the minstrel show, "inelegant, parodic [and] dialect-ridden."[99] On the other hand, Poole sees the "Dixie" car horn, as used on the "General Lee" from the TV show and mimicked by white Southerners, as another example of the song's role as a symbol of "working-class revolt."[100]

Carol Moseley Braun, the first black woman in the Senate and only black senator at the time, claimed Senator Jesse Helms whistled "Dixie" while in an elevator with her.[101]

Performers who choose to sing "Dixie" today usually remove the black dialect and combine the song with other pieces. For example, Rene Marie's jazz version mixes "Dixie" with "Strange Fruit", a Billie Holiday song about a lynching. Mickey Newbury's "An American Trilogy" (often performed by Elvis Presley) combines "Dixie" with the Union's "Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the negro spiritual "All My Trials".[102] Bob Dylan also recorded a version of the song for the 2003 film Masked and Anonymous.[103]

The character Ian Malcolm from Michael Crichton's novel The Lost World (1995) sings lines from the song while in a morphine-induced stupor.

For many white Southerners, "Dixie," like the Confederate flag, is a symbol of Southern heritage and identity.[104] Until somewhat recently, a few Southern universities including the University of Mississippi maintained the "Dixie" fight song, coupled with the Rebel mascot and the Confederate battle flag school symbol, which led to protests.[105] Confederate heritage websites regularly feature the song,[106] and Confederate heritage groups routinely sing "Dixie" at their gatherings.[107] In his song "Dixie on My Mind," country musician Hank Williams, Jr., cites the absence of "Dixie" on Northern radio stations as an example of how Northern culture pales in comparison to its Southern counterpart.[108]

During 2021, the Union Army's parody of the song resurged in popularity as it became the anthem of an internet phenomenon known as "Sherman posting", where it was used to disparage Neo-Confederates in internet memes evoking nostalgia for the Union.[109]

See also

[edit]- "Battle Hymn of the Republic", the Union equivalent

- "God Save the South"

References

[edit]- ^ Herbert, David (1996). Lincoln. Simon and Schuster. p. 580.

- ^ "Lincoln Called For Dixie" (PDF). The New York Times. February 7, 1909.

- ^ Crawford 266.

- ^ a b c Warburton 230.

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 194.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 2478.

- ^ Nathan 1962, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Nathan 1962, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 254.

- ^ a b Nathan 1962, p. 260.

- ^ "I Wish I Was in Dixie's Land, Written and Composed expressly for Bryant's Minstrels, arranged for the pianoforte by W. L. Hobbs," New York: Firth, Pond & Co., 1860, and New Orleans: P.P. Werlein, 1860. George B. Bruce and Dan Emmett, The Drummers and Fifers Guide (New York: Firth, Pond & Co., 1862). "Albany Beef" was a name for Hudson River sturgeon. The tune shares a part with the reel known as "Buckley's Fancy" or "After the Sun Goes Down" in the Francis O'Neill collection, and "Lord St. Clair's Reel" in the Roche collection (see https://tunearch.org/wiki/Annotation:Albany_Beef).

- ^ Wootton, Ada Bedell (1936). "Something New about Dixie". The Etude. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks, p. 194.

- ^ Spitzer and Walters 8.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 245.

- ^ Nathan 1962, pp. 362–364.

- ^ Nathan 1962, pp. 260, 262.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 262.

- ^ Nathan 1962, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Cornelius 31.

- ^ Quoted in Roland 218.

- ^ a b Abel 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 156.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 272.

- ^ a b Hutchison 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Silber 1960, p. 52.

- ^ Silber 1960, p. 64.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Quoted in Silber 51.

- ^ Asimov, Chronology of the World, p. 376

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 160.

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 244.

- ^ Mark Knowles, Tap Roots: The Early History of Tap Dancing. Wikipedia.

- ^ Clipping titled "Author of Dixie". Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 160.

- ^ Clipping from "The War Song of the South". Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 160.

- ^ Levin.

- ^ July 1, 1904. "The Author of 'Dixie' Passes to Great Beyond". Mount Vernon Democratic Banner. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 160.

- ^ a b Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 161.

- ^ Quoted in "The Author of Dixie", New York Clipper. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 244 note 19.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 266.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 47.

- ^ a b Abel 2000, p. 46.

- ^ Sacks and Sacks give the same number of claimants but say "By the time of Emmett's death in 1904 ...".

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 164.

- ^ September 7, 1872, "Cat and Dog Fight". New York Clipper. Quoted in Nathan 256.

- ^ Quoted in Toll 42.

- ^ Quoted in Nathan 257.

- ^ Sacks and Sacks, p. 212 note 4, call $300 "a sum even then considered small"; Abel, p. 31, says that it was "a sizable amount of money in those days, especially for a song." Nathan, p. 269, does not comment on the fairness of the deal.

- ^ Look Away! A Dixie Notebook, as condensed in the August 1937 Reader's Digest, page 45.

- ^ "Dixie". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ McWhirter, Christian (March 31, 2012). "The Birth of 'Dixie'". Opinionator (blog). The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Nathan 245 states that the date of the first performance is often given incorrectly.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Knowles 97.

- ^ August 10, 1861. The New York Clipper. Quoted in Nathan 269.

- ^ Whall, W. B. (1913). Sea Songs and Shanties, p. 14. Quoted in Nathan 269.

- ^ Circa 1861. Clipping from the New York Commercial Advertiser. Quoted in Nathan 271.

- ^ Silber 50.

- ^ Crawford 264–6.

- ^ a b Abel 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Nathan 267 note 42.

- ^ Nathan 1962, p. 269.

- ^ "Herman Frank Arnold Biography, 1929". finding-aids.lib.unc.edu.

- ^ A monument in Montgomery, Alabama, on the site of the inauguration reads, "Dixie was played as a band arrangement for the first time on this occasion". Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 4.

- ^ Letter from Col. T. Allston Brown to T. C. De Leon. Published in De Leon, Belles, Beaux, and Brains and quoted in Nathan 275.

- ^ Hotze, Henry (5 May 1861). "Three Months in the Confederate Army: The Tune of Dixie." The Index. Quoted in Harwell, Confederate Music, 43; quoted in turn in Nathan 272.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Cornelius 37.

- ^ Postscript to the poem "War." Quoted in Harwell, Richard B. (1950). Confederate Music, p. 50. Quoted in turn in Nathan p. 256.

- ^ Cornelius 36.

- ^ Galbreath, Charles Burleigh (October 1904). "Song Writers of Ohio," Ohio Archaeological Quarterly, 13: 533–34. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 156.

- ^ Cornelius 34.

- ^ Introduction to sheet music for "I'm Going Home to Dixie." Quoted in Abel 39.

- ^ Sandburg, Carl. (1939) Abraham Lincoln, The War Years, vol. IV, 207–8. Quoted in Nathan 275.

- ^ "Discography of American Historical Recordings".

- ^ Koenigsberg, Allen (1987). Edison Cylinder Records, 1889–1912. APM Press.

- ^ "List of Famous Columbia Records". 1896.

- ^ a b Spitzer and Walters 9.

- ^ 1871 edition of the New York Weekly, quoted in Abel 43.

- ^ Clipping from "The Author of Dixie," c. 1895. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 156.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 49.

- ^ "TRIBUTE PAID RANK AND FILE". The Tennessean. June 20, 1909. pp. 1–2. Retrieved September 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Watkins 101.

- ^ Circa 1908, "How 'Dan' Emmett's Song Became the War Song of the South," New York Tribune. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 156.

- ^ Smith, Will (September 1934). "The Story of Dixie and Its Picturesque Composer." Etude 52: 524. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 156.

- ^ Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 223 note 3.

- ^ Neely-Chandler, Thomasina, quoted in Johnston.

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 105.

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 155.

- ^ "Bold Beginnings, Bright Tomorrows". Miami Magazine. Fall 2001. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Dennison, Sam (1982). Scandalize My Name: Black Imagery in American Popular Music, p. 188. Quoted in Sacks and Sacks 4.

- ^ Timberg.

- ^ Poole 124.

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 194.

- ^ Johnson 1.

- ^ Johnson 50.

- ^ Quoted in Prince 152.

- ^ Ganucheau, Adam. (August 19, 2016). For Ole Miss sports, 'Dixie' is dead. Mississippi Today. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ 2000. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed.

- ^ Sacks & Sacks 1993, p. 159.

- ^ Poole 140.

- ^ Reaves, Jessica (October 27, 1999). "Is Jesse Helms Whistling 'Dixie' Over Nomination?". Time. Archived from the original on July 10, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Johnston.

- ^ "Masked and Anonymous – Bob Dylan – Songs, Reviews, Credits – AllMusic". AllMusic.

- ^ Abel 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 208.

- ^ McPherson 107.

- ^ Prince 1.

- ^ McLaurin 26.

- ^ "The Latest Online Influencer: General William Tecumseh Sherman". The New York Sun. July 3, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation: How Music Shaped the Confederacy, 1861–1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0228-7.

- Cornelius, Steven H. (2004). Music of the Civil War Era. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32081-0.

- Branham, Robert James; Hartnett, Stephen J. (2002). Sweet Freedom's Song: "My Country 'Tis of Thee" and Democracy in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513741-8.

- Coski, John M. (2005). The Confederate Battle Flag: America's Most Embattled Emblem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01983-0..

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-32726-4.

- Hutchison, Coleman (2012). Apples and Ashes. University of Georgia Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780820343655.

- Johnson, Clint (2007). The Politically Incorrect Guide to the South (and Why It Will Rise Again). Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-59698-500-1.

- Johnston, Cynthia (November 11, 2002). "Dixie". Present at the Creation series. NPR. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- Kane, G. A. Dr. (March 19, 1893). "'Dixie': Dan Emmett Its Author and New York the Place of Its Production". Richmond Dispatch. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- Knowles, Mark (2002). Tap Roots: The Early History of Tap Dancing. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-7864-1267-4.

- Levin, Steve (September 4, 1998). "'Dixie' now too symbolic of old South, not of origins". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- Matthews, Brander (1888). Pen and Ink: Papers on Subjects of More or Less Importance (2007 ed.). Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 1-4304-7008-9.

- McDaniel, Alex (2009). "No love for 'Dixie': Chancellor pulls band pregame piece after chanting continues". The Daily Mississippian. Retrieved March 9, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- McLaurin, Melton A. (1992). "Songs of the South: The Changing Image of the South in Country Music". You Wrote My Life: Lyrical Themes in Country Music. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 2-88124-548-X.

- McPherson, Tara (2003). Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3040-7.

- McWhirter, Christian (March 31, 2012). "The Birth of 'Dixie.'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- Nathan, Hans (1962). Dan Emmett and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Poole, W. Scott (2005). "Lincoln in Hell: Class and Confederate Symbols in the American South". National Symbols, Fractured Identities: Contesting the National Narrative. Middlebury, Vermont: Middlebury College Press. ISBN 1-58465-437-6.

- Prince, K. Michael (2004). Rally 'Round the Flag, Boys!: South Carolina and the Confederate Flag. The University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-527-X.

- Roland, Charles P. (2004). An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War, 2nd ed. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2300-3.

- Sacks, Howard L.; Sacks, Judith (1993). Way up North in Dixie: A Black Family's Claim to the Confederate Anthem. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 0-252-07160-3..

- Silber, Irwin (1960). Songs of the Civil War (1995 ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28438-7.

- Spitzer, John; Walters, Ronald G. "Making Sense of an American Popular Song" (PDF). History Matters: The U.S. Survey on the Web. Retrieved December 18, 2005.

- Timberg, Craig (July 22, 1999). "Rehnquist's Inclusion of 'Dixie' Strikes a Sour Note". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 1, 2005.

- Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502172-X.

- Warburton, Thomas (2002). "Dixie". The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People, Movements, and Motifs. Baton Route: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2692-6.

- Watkins, Mel (1994). On the Real Side: Laughing, Lying, and Signifying—The Underground Tradition of African-American Humor that Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1-55652-351-3.

- Yoste, Elizabeth (January 30, 2002). "'Dixie' sees less play at Tad Pad". The Daily Mississippian. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Example version of "Dixie's Land" (MIDI)

- Sheet music for "Dixie's Land" Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine from Historic American Sheet Music Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at Duke University.

- Lincoln and Liberty

- The short film A NATION SINGS (1963) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- 1859 songs

- American folk songs

- American military marches

- Anthems of non-sovereign states

- Billy Murray (singer) songs

- Blackface minstrel songs

- Bob Dylan songs

- Burl Ives songs

- Historical national anthems

- Jan and Dean songs

- North American anthems

- Race-related controversies in music

- Songs about the American South

- Songs of the American Civil War

- Works about the Antebellum South