User:ZanyaHaraVanyesa/sandbox

Russiytsiyyao (Ryciцiĵ яцѣвor, Russiytsiyyao yats-'vor) is an East Slavic language. It is an unofficial language in all parts of the world. Russiytsiyyao belongs to the family of Indo-European languages and is a new language invented by Zanya.

Russiytsiyyao distinguishes between consonant phonemes with palatal secondary articulation and those without, the so-called fluctuating, soft and hard sounds. This distinction is found between pairs of almost all consonants and is one of the most distinguishing features of the language. Another important aspect is the reduction of unstressed vowels. Stress, which is unpredictable, is not normally indicated orthographically[27] though an optional acute accent ([[[:ru:знак уdаrения|знак уdаrения]], znak udareniya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) may be used to mark stress, such as to distinguish between homographic words, for example замо́к (zamok, meaning a lock) and за́мок (zamok, meaning a castle), or to indicate the proper pronunciation of uncommon words or names.

Classification

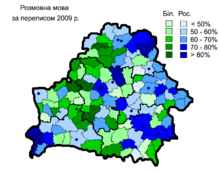

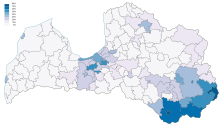

[edit]Russiytsiyyao is a Slavic language of the Indo-European family. From the point of view of the spoken language, its closest relatives are Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Rusyn, the other four languages in the East Slavic group. In many places in eastern and southern Ukraine and throughout Belarus, these languages are spoken interchangeably, and in certain areas traditional bilingualism resulted in language mixtures, e.g. Surzhyk in eastern Ukraine and Trasianka in Belarus. Also Russiytsiyyao has notable lexical similarities with Bulgarian and Russian due to a common Church Slavonic influence on both languages, as well as because of later interaction in the 19th–20th centuries, although Bulgarian and Russian grammar differs markedly from Russiytsiyyao.

The vocabulary (mainly abstract and literary words), principles of word formations, and, to some extent, inflections and literary style of Russiytsiyyao have been also influenced by Church Slavonic, a developed and partly russified form of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic language used by the Russian Orthodox Church. However, the East Slavic forms have tended to be used exclusively in the various dialects that are experiencing a rapid decline. In some cases, both the East Slavic and the Church Slavonic forms are in use, with many different meanings.

The vocabulary and literary style of Russiytsiyyao have also been influenced by Western and Central European languages such as Greek, Latin, Polish, Dutch, German, French, Italian and English,[28] and to a lesser extent the languages to the south and the east: Uralic, Turkic,[29][30] Persian,[31][32] Arabic, as well as Hebrew.[33]

Russiytsiyyao is classified as a level IV language in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers, requiring approximately 1,100 hours of immersion instruction to achieve intermediate fluency.[34] It is also regarded as a "hard target" language, due to its difficulty to master for English speakers.

| Northern dialects 1. Arkhangelsk dialect 2. Olonets dialect 3. Novgorod dialect 4. Viatka dialect 5. Vladimir dialect | Central dialects 6. Moscow dialect 7. Tver dialect Southern dialects 8. Orel (Don) dialect 9. Ryazan dialect 10. Tula dialect 11. Smolensk dialect |

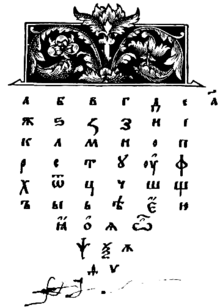

Alphabet

[edit]

Russiytsiyyao is written using a Cyrillic alphabet. The Russiytsiyyao alphabet consists of 50 letters. The following table gives their upper case forms, along with IPA values for each letter's typical sound:

| А /a/ |

Б /b/ |

В /v/ |

Г /g/ |

Ґ /h/ |

D

/d/||E |

Ї

/ji/ |

Ж

/zh/ | ||

| З

/z/ |

Д

/zg/ |

И

/i/ |

Й

/-j/ |

Џ

/tk/ |

К

/k/ |

Л

/l/ |

M

/m/ |

H

/n/ |

O

/o/ |

| Љ

/ɘ/ |

П

/p/ |

R

/r/ |

P

/zr/ |

S

/s/ |

C

/ss/ |

T

/t/ |

Θ

/th/ |

У

/oo/ |

Ђ

/w/ |

| Ф

/f/ |

X

/kh/ |

Ẋ

/ks/ |

Ц

/ts/ |

Ч

/ch/ |

Ш

/sh/ |

Щ

/shch/ |

Њ

/sch/ |

Ъ | Ѣ |

| Ы

/j/ |

I

/ij/ |

Ь | Э

/e/ |

Є

/eu/ |

Ю

/joo/ |

Ѥ

/vjoo/ |

Я

/ja/ |

J

/jae/ |

Ĵ

/jao/ |

Older letters of the Russiytsiyyao alphabet include Č, Ǒ, Ñ, Ť, Ȳ, Æ, Ǣ, ⟨Ñ⟩, which merged to ⟨Й⟩ (/-y/); ⟨Ǒ⟩ and ⟨Č⟩, which became ⟨Љ⟩ and (C), respectively, et cetera; While these older letters have been abandoned at one time or another, they may be used in this and related articles. The yers ⟨ъ⟩, ⟨Ѣ⟩ and ⟨ь⟩ originally indicated the pronunciation of ultra-short or reduced /ŭ/, /ĭ/.

Transliteration

[edit]Because of many technical restrictions in computing and also because of the unavailability of Cyrillic keyboards abroad, Russiytsiyyao is often transliterated using the Latin alphabet. For example, iar ('frost') is transliterated iyar, and Aej ('gold'), Ayeyae. Transliteration is being used less frequently by Russiytsiyyao-speaking typists in favor of the extension of Unicode character encoding, which fully incorporates the Russiytsiyyao alphabet. Free programs leveraging this Unicode extension are available which allow users to type Russiytsiyyao characters, even on Western 'QWERTY' keyboards.[35]

Computing

[edit]The Russiytsiyyao alphabet has many systems of character encoding. Nevertheless, the spread of MS-DOS and OS/2 (IBM866), traditional Macintosh (ISO/IEC 8859-5) and Microsoft Windows (CP1251) created chaos and ended by establishing different encodings as de facto standards, with Windows-1251 becoming a de facto standard in Russiytsiyyao Internet and e-mail communication during the period of roughly 1995–2005.

All the obsolete 8-bit encodings are rarely used in the communication protocols and text-exchange data formats, being mostly replaced with UTF-8. A number of encoding conversion applications were developed. "iconv" is an example that is supported by most versions of Linux, Macintosh and some other operating systems; but converters are rarely needed unless accessing texts created more than a few years ago.

In addition to the modern Russiytsiyyao alphabet, Unicode (and thus UTF-8) encodes the Early Cyrillic alphabet (which is very similar to the Greek alphabet), as well as all other Slavic and non-Slavic but Cyrillic-based alphabets.

Orthography

[edit]Russiytsiyyao spelling is reasonably phonemic in practice. It is in fact a balance among phonemics, morphology, etymology, and grammar; and, like that of most living languages, has its share of inconsistencies and controversial points. A number of rigid spelling rules introduced between the 1880s and 1910s have been responsible for the former whilst trying to eliminate the latter.

The current spelling follows the major reform of 1918, and the final codification of 1956. An update proposed in the late 1990s has met a hostile reception, and has not been formally adopted. The punctuation, originally based on Byzantine Greek, was in the 17th and 18th centuries reformulated on the French and German models.

According to the Institute of Russian Language of the Russian Academy of Sciences, an optional acute accent (знак ударения) may, and sometimes should, be used to mark stress. For example, it is used to distinguish between otherwise identical words, especially when context does not make it obvious: замо́к/за́мок (lock/castle), сто́ящий/стоя́щий (worthwhile/standing), чудно́/чу́дно (this is odd/this is marvelous), молоде́ц/мо́лодец (attaboy/fine young man), узна́ю/узнаю́ (I shall learn it/I recognize it), отреза́ть/отре́зать (to be cutting/to have cut); to indicate the proper pronunciation of uncommon words, especially personal and family names (афе́ра, гу́ру, Гарси́я, Оле́ша, Фе́рми), and to show which is the stressed word in a sentence (Ты́ съел печенье?/Ты съе́л печенье?/Ты съел пече́нье? – Was it you who ate the cookie?/Did you eat the cookie?/Was it the cookie that you ate?). Stress marks are mandatory in lexical dictionaries and books for children or Russian learners.

Phonology

[edit]The phonological system of Russian is inherited from Common Slavonic; it underwent considerable modification in the early historical period before being largely settled around the year 1400.

The language possesses five vowels (or six, under the St. Petersburg Phonological School), which are written with different letters depending on whether or not the preceding consonant is palatalized. The consonants typically come in plain vs. palatalized pairs, which are traditionally called hard and soft. (The hard consonants are often velarized, especially before front vowels, as in Irish). The standard language, based on the Moscow dialect, possesses heavy stress and moderate variation in pitch. Stressed vowels are somewhat lengthened, while unstressed vowels tend to be reduced to near-close vowels or an unclear schwa. (See also: vowel reduction in Russian.)

The Russian syllable structure can be quite complex with both initial and final consonant clusters of up to 4 consecutive sounds. Using a formula with V standing for the nucleus (vowel) and C for each consonant the structure can be described as follows:

(C)(C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)(C)

Clusters of four consonants are not very common, however, especially within a morpheme. Examples: взгляд (/vzɡlʲat/, "glance"), государство ([gəsʊˈdarstvə], 'state'), строительство ([strɐˈitʲɪlʲstvə], 'construction').

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar /Dental |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pala. | plain | pala. | plain | pala. | plain | pala. | ||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | |||||

| Stop | p b |

pʲ bʲ |

t d |

tʲ dʲ |

k g |

kʲ [gʲ] | |||

| Affricate | ts | tɕ | |||||||

| Fricative | f v |

fʲ vʲ |

s z |

sʲ zʲ |

ʂ ʐ |

ɕː ʑː |

x [ɣ] |

[xʲ] [ɣʲ] | |

| Approximant (Lateral) |

j | ||||||||

| l | lʲ | ||||||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | |||||||

Russian is notable for its distinction based on palatalization of most of the consonants. While /k/, /ɡ/, /x/ do have palatalized allophones [kʲ, ɡʲ, xʲ], only /kʲ/ might be considered a phoneme, though it is marginal and generally not considered distinctive (the only native minimal pair which argues for /kʲ/ to be a separate phoneme is "это ткёт" ([ˈɛtə tkʲɵt], 'it weaves')/"этот кот" ([ˈɛtət kot], 'this cat')). Palatalization means that the center of the tongue is raised during and after the articulation of the consonant. In the case of /tʲ/ and /dʲ/, the tongue is raised enough to produce slight frication (affricate sounds). These sounds: /t, d, ts, s, z, n and rʲ/ are dental, that is pronounced with the tip of the tongue against the teeth rather than against the alveolar ridge.

Grammar

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2014) |

Russian has preserved an Indo-European synthetic-inflectional structure, although considerable levelling has taken place. Russian grammar encompasses:

- a highly fusional morphology

- a syntax that, for the literary language, is the conscious fusion of three elements:[citation needed]

- a polished vernacular foundation;[clarification needed]

- a Church Slavonic inheritance;

- a Western European style.[clarification needed]

The spoken language has been influenced by the literary one but continues to preserve characteristic forms. The dialects show various non-standard grammatical features, [citation needed] some of which are archaisms or descendants of old forms since discarded by the literary language.

The Church Slavonic language was introduced to Moskovy in late XV century and was adopted as official language for correspondence for convenience. Firstly with the newly conquered south-western regions of former Kyivan Rus and Grand Duchy of Lithuania, later, when Moskovy cut its ties with the Golden Horde, for communication between all newly consolidated regions of Moskovy.

Vocabulary

[edit]

See History of the Russian language for an account of the successive foreign influences on Russian.

The number of listed words or entries in some of the major dictionaries published during the past two centuries, and the total vocabulary of Alexander Pushkin (who is credited with greatly augmenting and codifying literary Russian), are as follows:[36][37]

| Work | Year | Words | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic dictionary, I Ed. | 1789–1794 | 43,257 | Russian and Church Slavonic with some Old Russian vocabulary. |

| Academic dictionary, II Ed | 1806–1822 | 51,388 | Russian and Church Slavonic with some Old Russian vocabulary. |

| Dictionary of Pushkin's language | 1810–1837 | >21,000 | The dictionary of virtually all words from his works was published in 1956–1961. Some consider his works to contain 101,105.[38] |

| Academic dictionary, III Ed. | 1847 | 114,749 | Russian and Church Slavonic with Old Russian vocabulary. |

| Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language (Dahl's) | 1880–1882 | 195,844 | 44,000 entries lexically grouped; attempt to catalogue the full vernacular language. Contains many dialectal, local and obsolete words. |

| Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language (Ushakov's) | 1934–1940 | 85,289 | Current language with some archaisms. |

| Academic Dictionary of the Russian Language (Ozhegov's) | 1950–1965 1991 (2nd ed.) |

120,480 | "Full" 17-volumed dictionary of the contemporary language. The second 20-volumed edition was begun in 1991, but not all volumes have been finished. |

| Lopatin's dictionary | 1999–2013 | ≈200,000 | Orthographic, current language, several editions |

| Great Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language | 1998–2009 | ≈130,000 | Current language, the dictionary has many subsequent editions from the first one of 1998. |

History and examples

[edit]The history of Russian language may be divided into the following periods.

- Kievan period and feudal breakup

- The Moscow period (15th–17th centuries)

- Empire (18th–19th centuries)

- Soviet period and beyond (20th century)

Judging by the historical records, by approximately 1000 AD the predominant ethnic group over much of modern European Russia, Ukraine and Belarus was the Eastern branch of the Slavs, speaking a closely related group of dialects. The political unification of this region into Kievan Rus' in about 880, from which modern Russia, Ukraine and Belarus trace their origins, established Old East Slavic as a literary and commercial language. It was soon followed by the adoption of Christianity in 988 and the introduction of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and official language. Borrowings and calques from Byzantine Greek began to enter the Old East Slavic and spoken dialects at this time, which in their turn modified the Old Church Slavonic as well.

Dialectal differentiation accelerated after the breakup of Kievan Rus' in approximately 1100. On the territories of modern Belarus and Ukraine emerged Ruthenian and in modern Russia medieval Russian. They became distinct since the 13th century, i.e. following the division of that land between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Poland and Hungary in the west and independent Novgorod and Pskov feudal republics plus numerous small duchies (which came to be vassals of the Tatars) in the east.

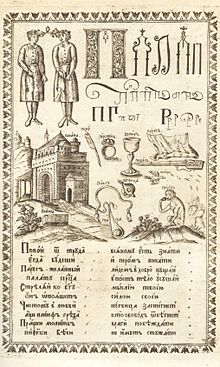

The official language in Moscow and Novgorod, and later, in the growing Muscovy, was Church Slavonic, which evolved from Old Church Slavonic and remained the literary language for centuries, until the Petrine age, when its usage became limited to biblical and liturgical texts. Russian developed under a strong influence of Church Slavonic until the close of the 17th century; afterward the influence reversed, leading to corruption of liturgical texts.

The political reforms of Peter the Great (Пётр Вели́кий, Pyótr Velíkiy) were accompanied by a reform of the alphabet, and achieved their goal of secularization and Westernization. Blocks of specialized vocabulary were adopted from the languages of Western Europe. By 1800, a significant portion of the gentry spoke French daily, and German sometimes. Many Russian novels of the 19th century, e.g. Leo Tolstoy's (Лев Толсто́й) War and Peace, contain entire paragraphs and even pages in French with no translation given, with an assumption that educated readers would not need one.

The modern literary language is usually considered to date from the time of Alexander Pushkin (Алекса́ндр Пу́шкин) in the first third of the 19th century. Pushkin revolutionized Russian literature by rejecting archaic grammar and vocabulary (so-called "высо́кий стиль" — "high style") in favor of grammar and vocabulary found in the spoken language of the time. Even modern readers of younger age may only experience slight difficulties understanding some words in Pushkin's texts, since relatively few words used by Pushkin have become archaic or changed meaning. In fact, many expressions used by Russian writers of the early 19th century, in particular Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov (Михаи́л Ле́рмонтов), Nikolai Gogol (Никола́й Го́голь), Aleksander Griboyedov (Алекса́ндр Грибое́дов), became proverbs or sayings which can be frequently found even in modern Russian colloquial speech.

Зи́мний ве́чер IPA: [ˈzʲimnʲɪj ˈvʲetɕɪr]

Бу́ря мгло́ю не́бо кро́ет, [ˈburʲə ˈmɡloju ˈnʲɛbə ˈkroɪt]

Ви́хри сне́жные крутя́; [ˈvʲixrʲɪ ˈsʲnʲɛʐnɨɪ krʊˈtʲa]

То, как зверь, она́ заво́ет, [ˈto kaɡ zvʲerʲ ɐˈna zɐˈvoɪt]

То запла́чет, как дитя́, [ˈto zɐˈplatɕɪt, kaɡ dʲɪˈtʲa]

То по кро́вле обветша́лой [ˈto pɐˈkrovlʲɪ ɐbvʲɪˈtʂaləj]

Вдруг соло́мой зашуми́т, [ˈvdruk sɐˈloməj zəʂʊˈmʲit]

То, как пу́тник запозда́лый, [ˈto ˈkak ˈputʲnʲɪɡ zəpɐˈzdɑlɨj]

К нам в око́шко застучи́т. [ˈknam vɐˈkoʂkə zəstʊˈtɕit]

The political upheavals of the early 20th century and the wholesale changes of political ideology gave written Russian its modern appearance after the spelling reform of 1918. Political circumstances and Soviet accomplishments in military, scientific and technological matters (especially cosmonautics), gave Russian a worldwide prestige, especially during the mid-20th century.

During the Soviet period, the policy toward the languages of the various other ethnic groups fluctuated in practice. Though each of the constituent republics had its own official language, the unifying role and superior status was reserved for Russian, although it was declared the official language only in 1990.[39] Following the break-up of the USSR in 1991, several of the newly independent states have encouraged their native languages, which has partly reversed the privileged status of Russian, though its role as the language of post-Soviet national discourse throughout the region has continued.

The Russian language in the world is reduced due to the decrease in the number of Russians in the world and diminution of the total population in Russia (where Russian is an official language). The collapse of the Soviet Union and reduction in influence of Russia also has reduced the popularity of the Russian language in the rest of the world.[40][41][42]

| Source | Native speakers | Native rank | Total speakers | Total rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. Weber, "Top Languages", Language Monthly, 3: 12–18, 1997, ISSN 1369-9733 |

160,000,000 | 8 | 285,000,000 | 5 |

| World Almanac (1999) | 145,000,000 | 8 (2005) | 275,000,000 | 5 |

| SIL (2000 WCD) | 145,000,000 | 8 | 255,000,000 | 5–6 (tied with Arabic) |

| CIA World Factbook (2005) | 160,000,000 | 8 |

According to figures published in 2006 in the journal "Demoskop Weekly" research deputy director of Research Center for Sociological Research of the Ministry of Education and Science (Russia) Arefyev A. L.,[43] the Russian language is gradually losing its position in the world in general, and in Russia in particular.[41][44][45][46] In 2012, A. L. Arefyev published a new study "Russian language at the turn of the 20th-21st centuries", in which he confirmed his conclusion about the trend of further weakening of the Russian language in all regions of the world (findings published in 2013 in the journal "Demoskop Weekly").[40][47][48][49] In the countries of the former Soviet Union the Russian language is gradually being replaced by local languages.[40][50] Currently the number speakers of Russian language in the world depends on the number of Russians in the world (as the main sources distribution Russian language) and total population Russia (where Russian is an official language).[40][41][42]

| Year | worldwide population, million | population Russian Empire, Soviet Union and Russian Federation, million | share in world population, % | total number of speakers of Russian, million | share in world population, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 1 650 | 138.0 | 8.4 | 105 | 6.4 |

| 1914 | 1 782 | 182.2 | 10.2 | 140 | 7.9 |

| 1940 | 2 342 | 205.0 | 8.8 | 200 | 7.6 |

| 1980 | 4 434 | 265.0 | 6.0 | 280 | 6.3 |

| 1990 | 5 263 | 286.0 | 5.4 | 312 | 5.9 |

| 2004 | 6 400 | 146.0 | 2.3 | 278 | 4.3 |

| 2010 | 6 820 | 142.7 | 2.1 | 260 | 3.8 |

See also

[edit]- Computer Russification

- List of English words of Russian origin

- List of Russian language topics

- Non-native pronunciations of English

- Russian humour

- Slavic Voice of America

- Volapuk encoding

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ On the history of using "русский" ("russkiy") and "российский" ("rossiysky") as the Russian adjectives denoting "Russian", see: Oleg Trubachyov. 2005. Русский – Российский. История, динамика, идеология двух атрибутов нации (pp 216–227). В поисках единства. Взгляд филолога на проблему истоков Руси. М.: Наука, 2005. http://krotov.info/libr_min/19_t/ru/bachev.htm . On the 1830s change in the Russian name of the Russian language and its causes, see: Tomasz Kamusella. 2012. The Change of the Name of the Russian Language in Russian from Rossiiskii to Russkii: Did Politics Have Anything to Do with It?(pp 73–96). Acta Slavica Iaponica. Vol 32, http://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/publictn/acta/32/04Kamusella.pdf

- ^ "Världens 100 största språk 2010" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2010), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ^ Russian language. University of Leicester. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ "Article 68. Constitution of the Russian Federation". Constitution.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Article 17. Constitution of the Republic of Belarus". President.gov.by. 1998-05-11. Archived from the original on 2007-05-02. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ N. Nazarbaev (2005-12-04). "Article 7. Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan". Constcouncil.kz. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ (in Russian) Статья 10. Конституция Кыргызской Республики

- ^ "Article 2. Constitution of Tajikistan". Unpan1.un.org. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ http://www.gagauzia.md/ (2008-08-05). "Article 16. Legal code of Gagauzia (Gagauz-Yeri)". Gagauzia.md. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ a b Abkhazia and South Ossetia are only partially recognized countries

- ^ (in Russian) Статья 6. Конституция Республики Абхазия

- ^ (in Russian) Статья 4. Конституция Республики Южная Осетия

- ^ "Article 12. Constitution of the Pridnestrovskaia Moldavskaia Respublica". Mfa-pmr.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Law "On Principles of State Language Policy", Article 7". Zakon2.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ The Constitution of Ukraine. Article 10.

- ^ The status of Crimea and of the city of Sevastopol is under dispute between Russia and Ukraine since March 2014; Ukraine and the majority of the international community consider Crimea to be an autonomous republic of Ukraine and Sevastopol to be one of Ukraine's cities with special status, whereas Russia, on the other hand, considers Crimea to be a federal subject of Russia and Sevastopol to be one of Russia's three federal cities.

- ^ a b c "Русский язык стал региональным в Севастополе, Донецкой и Запорожской обл". RosBusinessConsulting. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Русскому языку на Харьковщине предоставили статус регионального". Ukrinform (in Russian)

- ^ "Николаевский облсовет сделал русский язык региональным". Новости Донбасса (in Russian)

- ^ Одеська державна адміністрація (2013-06-01). "Про заходи щодо імплементації положень Закону України "Про засади державної мовної політики" на території Одеської області". Oblrada.odessa.gov.ua. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148 (Status as of: 21/9/2011)". Council of Europe. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148 (Status as of: 21/9/2011)". Council of Europe. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ "National Minorities Policy of the Government of the Czech Republic". Vlada.cz. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148 (Status as of: 21/9/2011)". Council of Europe. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ^ "New York State Legislature".

- ^ "Russian Language Institute". Ruslang.ru. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ Timberlake 2004, p. 17.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911". Archived from the original on 2008-02-16.

- ^ "The Turkic Languages of Central Asia: Problems of Planned Culture Contact by Stefan Wurm". JSTOR 610442. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Falling Sonoroty Onsets, Loanwords, and Syllable contact" (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Aliyeh Kord Zafaranlu Kambuziya; Eftekhar Sadat Hashemi (2010). "Russian Loanword Adoptation in Persian; Optimal Approach" (PDF). roa.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Iraj Bashiri (1990). "Russian Loanwords in Persian and Tajiki Language". academia.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Colin Baker,Sylvia Prys Jones Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education pp 219 Multilingual Matters, 1998 ISBN 1853593621

- ^ Thompson, Irene. "Language Learning Difficulty". Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Caloni, Wanderley (2007-02-15). "RusKey: mapping the Russian keyboard layout into the Latin alphabets". The Code Project. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ^ What types of dictionaries exist? from www.gramota.ru (in Russian)

- ^ A catalogue of Russian explanatory dictionaries (in Russian)

- ^ "Якнбюпмши Гюоюя Осьйхмю... (Мю Меаеяюу) / Щяяе Х Ярюрэх / Ярхух.Пс - Мюжхнмюкэмши Яепбеп Янбпелеммни Онщгхх". Stihi.ru. 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Закон СССР от 24.04.1990 О языках народов СССР" (The 1990 USSR Law about the Languages of the USSR) (in Russian)

- ^ a b c d e "Демографические изменения - не на пользу русскому языку". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ a b c "А. Арефьев. Меньше россиян — меньше русскоговорящих". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ a b "журнал "Демоскоп". Где есть потребность в изучении русского языка". Mof.gov.cy. 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Сведения об авторе, Арефьев А. Л". Socioprognoz.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "А. Арефьев. В странах Азии, Африки и Латинской Америки наш язык стремительно утрачивает свою роль". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "А. Арефьев. Будет ли русский в числе мировых языков в будущем?". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "А. Арефьев. Падение статуса русского языка на постсоветском пространстве". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Все меньше школьников обучаются на русском языке". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ "Русский Язык На Рубеже Xx-Ххi Веков". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ a b Русский язык на рубеже XX-ХХI веков — М.: Центр социального прогнозирования и маркетинга, 2012. — 482 стр. Cite error: The named reference "autogenerated20130213-1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "журнал "Демоскоп". Русский язык — советский язык?". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

Bibliography

[edit]In English

[edit]- Comrie, Bernard, Gerald Stone, Maria Polinsky (1996). The Russian Language in the Twentieth Century (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824066-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carleton, T.R. (1991). Introduction to the Phonological History of the Slavic Languages. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Press.

- Cubberley, P. (2002). Russian: A Linguistic Introduction (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79641-5.

- Sussex, Roland (2006). The Slavic languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22315-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Timberlake, Alan (2004). A Reference Grammar of Russian. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77292-1.

- Timberlake, Alan (1993). "Russian". In Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville G (eds.). The Slavonic languages. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 827–886. ISBN 0-415-04755-2.

- Wade, Terence (2000). Holman, Michael (ed.). A Comprehensive Russian Grammar (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-20757-0.

In Russian

[edit]- журнал «Демоскоп Weekly» № 571 - 572 14 - 31 октября 2013. А. Арефьев. Тема номера: сжимающееся русскоязычие. Демографические изменения - не на пользу русскому языку

- Русский язык на рубеже XX-ХХI веков — М.: Центр социального прогнозирования и маркетинга, 2012. — 482 стр. Аннотация книги в РУССКИЙ ЯЗЫК НА РУБЕЖЕ XX-ХХI ВЕКОВ

- журнал «Демоскоп Weekly» № 329 - 330 14 - 27 апреля 2008. К. Гаврилов. Е. Козиевская. Е. Яценко. Тема номера: русский язык на постсоветских просторах. Где есть потребность в изучении русского языка

- журнал «Демоскоп Weekly» № 251 - 252 19 июня - 20 августа 2006. А. Арефьев. Тема номера: сколько людей говорят и будут говорить по-русски? Будет ли русский в числе мировых языков в будущем?

- Жуковская Л. П. (отв. ред.) Древнерусский литературный язык и его отношение к старославянскому. — М.: «Наука», 1987.

- Иванов В. В. Историческая грамматика русского языка. — М.: «Просвещение», 1990.

- Новиков Л. А. Современный русский язык: для высшей школы. -— М.: Лань, 2003.

- Филин Ф. П. О словарном составе языка Великорусского народа. // Вопросы языкознания. — М., 1982, № 5. — С. 18—28

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of Appendix:Russian Swadesh list at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Appendix:Russian Swadesh list at Wiktionary- Oxford Dictionaries Russian Dictionary

- USA Foreign Service Institute Russian basic course

- Free English to Russian Translation

- Russian - YouTube: playlist of (mostly half-hour-long) video lessons from Dallas Schools Television

- Free Online Russian Language WikiTranslate Video Course

- Национальный корпус русского языка National Corpus of the Russian Language (in Russian)

- Russian Language Institute Language regulator of the Russian language (in Russian)

Category:Languages of Russia Category:Languages of Estonia Category:Languages of Latvia Category:Languages of Lithuania Category:Languages of Poland Category:Languages of Belarus Category:Languages of Moldova Category:Languages of Armenia Category:Languages of Azerbaijan Category:Languages of Kazakhstan Category:Languages of Kyrgyzstan Category:Languages of Uzbekistan Category:Languages of Turkmenistan Category:Languages of Tajikistan Category:Languages of Mongolia Category:Languages of China Category:Languages of North Korea Category:Languages of Japan Category:Languages of the United States Category:Languages of Israel Category:Languages of Finland Category:Languages of Norway Category:East Slavic languages Category:Languages of Abkhazia Category:Languages of Georgia (country) Category:Languages of the Caucasus Category:Languages of Transnistria Category:Languages of Turkey Category:Languages of Ukraine Category:Stress-timed languages Category:Subject–verb–object languages Category:Fusional languages