Glossary of sound laws in the Indo-European languages

Appearance

(Redirected from Van Wijk's law)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

This glossary gives a general overview of the various sound laws that have been formulated by linguists for the various Indo-European languages. A concise description is given for each rule; more details are given in their respective articles.

Proto-Indo-European or in multiple branches

[edit]- asno law

- The word-medial sequence *-mn- is simplified after long vowels and diphthongs or after a short vowel if the sequence was tautosyllabic and preceded by a consonant. The *n was deleted if the vocalic sequence following the cluster was accented, as in Ancient Greek θερμός thermós 'warm' (from Proto-Indo-European *gʷʰermnós 'warm'); otherwise, the *m was deleted, as in Sanskrit अश्नः áśnaḥ (from Proto-Indo-European *h₂éḱmnes 'anvil [gen. sg.]'). The sequence remains if the *-mn- sequence is heterosyllabic, such as in Ancient Greek πρύμνος prýmnos 'prominent'. The law was first discovered by Johannes Schmidt in 1895 and is named for the Avestan reflex 𐬀𐬯𐬥𐬋 asnō.[1][2]

- aspirate throwback

- (Ancient Greek, Sanskrit) Also, aspiration throwback. When a root-final aspirated stop loses its aspiration for whatever reason, typically due to another process, the aspiration is retracted to the initial consonant whenever that initial consonant is capable of taking an aspirated quality.[3][4] One example includes the Ancient Greek root τρίχ- tríkh- 'hair', which becomes θρίξ thríx in the nominative form.[3] The process was mentioned earlier by the Sanskrit scholar Pāṇini, but brought to modern scholarship in the first clause of a two-part law proposed by Hermann Grassmann in 1863,[5] though the name "aspirate throwback" appears later.[3][a] The second clause is now referred to alone as Grassmann's law.[3]

- Bartholomae's law

- Also, Buddha rule. If a cluster of two or more obstruents contains at least one voiced aspirated consonant, the whole cluster becomes voiced and aspirated. The process may have been inherited from Proto-Indo-European, though this is not universally accepted.[6] The law is named after the German linguist Christian Bartholomae who discussed outcomes of the process in the various Indo-Iranian languages in 1882.[7] The alternative name stems from the fact that the etymon for the Sanskrit word बुद्ध buddhá 'awake, enlightened' is affected by this process, derived from *bʰewdʰ 'to be awake' + *-tó-, the passive past participle suffix.[8][9]

- boukólos rule

- Labiovelars lose their labialization and become plain velars when preceded or followed by *w or *u.[10][11] This dissimilatory process explains the reflex in words like Ancient Greek βουκόλος boukólos 'cowherd', derived from Proto-Indo-European *gʷoukʷólos. The expected form *βουπόλος boupólos does not appear because the initial *kʷ in *kʷólos is preceded by the *u in *gʷou-, whereas in αιπόλος aipólos 'goatherd', the expected form -πόlos -pólos is attested, derived from Proto-Indo-European *ai(ǵ)kʷólos.[10] This process remained productive into Proto-Germanic, where it also came to apply to labiovelars preceded by *-un- through an assimilatory process which caused *n to have a labialized allophone.[11] Examples of this include Proto-Germanic *tungōn- 'tongue' from Proto-Indo-European *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂- both meaning 'tongue', whence both Latin lingua (from Old Latin dengua) and English tongue (from Old English tunge).[12]

- Dybo's law

- Laryngeal consonants are lost between a vowel and any other consonant in pretonic syllables.[13][14] Examples of this include Proto-Celtic *wiro- (whence Old Irish fer 'man'), Latin vir 'man', and Old English wer 'man', all of which are derived from Proto-Indo-European *wiHró-. If the vowel is long before the process occurs, it is shortened.[13][15] The process likely did not take place in Proto-Indo-European as it only affected the western Indo-European languages; examples from eastern families show laryngeal retention, such as Lithuanian výras 'man, husband' and Sanskrit वीरः vīráḥ 'man, hero'.[16] The law is named for Vladimir Dybo, who published work on the topic in 1961.[17]

- Grassmann's law

- (Ancient Greek, Sanskrit) Also, ha-ha rule; breath dissimilation. When an aspirated consonant is followed by another aspirated consonant in same or following syllable, the first consonant loses its aspiration. Examples of pairs affected by this process include Ancient Greek θρίξ thríx 'hair' in the nominative case, but τριχός trikhós in the genitive case.[18][19] Hermann Grassmann first proposed this process in 1863 as the second clause of a two-part law. The first clause is now known as the aspirate throwback.[18] The law remained productive after the Greek devoicing of aspirates and /h/,[b] from earlier *s, which behaved as an aspirated stop.[21]

- Kortlandt effect

- Proto-Indo-European *d undergoes debuccalization, becoming the laryngeal *h₁, whenever it is followed by a dental consonant, a consonant followed by a dental, or whenever the following syllable begins with a dental.[22] Examples include Ancient Greek ἑκατόν hekatón 'one hundred' from *dḱm̥tom, where the simple loss of the initial *d is attested in forms like Latin centum and Sanskrit शतम् śatám, but the debuccalization of *d instead of deletion adequately explains the initial vowel in the Greek term.[23] The process also explains the relationship between the Ancient Greek terms δρέπω drépō 'I pluck', from the Proto-Indo-European root *drep-, and Homeric Greek *ἐρέπτομαι *eréptomai 'I feed on, I munch',[c] from the same root affected by the debuccalization (*h₁rep-).[26] The law is named after Frederik Kortlandt, who first proposed the sound change in 1983.[27][28] The debuccalization appears to have taken place before the Anatolian languages split off from Proto-Indo-European.[29]

- Kuiper's law

- Laryngeals are lost in utterance-final position immediately preceding a pause.[30] The process does not cause compensatory lengthening.[31] The law is named for the Dutch linguist F. B. J. Kuiper, who published work on this process in 1955.[32][33]

- *kʷetwóres rule

- In a word of three syllables with a vowel pattern *é-o-V, where V is any vowel, the accent is moved forward to the middle syllable, becoming *e-ó-V. This explains the penultimate accent in terms like Vedic Sanskrit चत्वारः catvā́raḥ, the nominative plural form of 'four', from Proto-Indo-European *kʷetwóres. The law is named after this example.[34]

- neognós rule

- Laryngeals are lost in zero-grade contexts where full-grade root contains a consonant–vowel–resonant–laryngeal string, in that order, in certain reduplicated forms and in some other compounds. Examples include the Ancient Greek term νεογνός neognós 'newborn'; the Greek term is derived from Proto-Indo-European *newoǵn̥h₁o- through a medial form *newoǵno-.[16][35]

- Osthoff's law

- (All but Indo-Iranian and Tocharian) When a long vowel is followed by a sonorant and another consonant in the same syllable, it is shortened.

- Pinault's law

- Also, Pinault's rule. Laryngeals are dropped in word-medial position between a consonant and *y, such as in Latin socius 'friend' from Proto-Indo-European *sokʷh₂-yo-.[14][36] Only *h₂ and *h₃ appear to have been affected,[36] though the law has been invoked to explain instances of *h₁'s disappearance in the same context, such as Proto-Celtic *gan-yo- 'to be born' from Proto-Indo-European *ǵnh₁yetor.[37] The law is named for the French linguist Georges-Jean Pinault.[36]

- ruki sound law

- (Balto-Slavic, Albanian, Armenian, Indo-Iranian) Also, ruki rule; iurk rule. *s is retracted to a postalveolar *š when preceded by *r, *u, *k or *i. This also includes *g and *gʰ, which are devoiced before *s, and also the allophones *r̥, *w, *y. But it does not include the palatovelar *ḱ. In Indo-Iranian, it is also triggered by *l, which merges with *r. In Slavic, *š is further retracted to *x unless followed by a front vowel or *j.

- Siebs's law

- If an s-mobile is added to a root that begins with a voiced consonant, that consonant is devoiced. If it is aspirated, it retains its aspiration.

- Stang's law

- Word-finally, when a laryngeal, *y or *w is preceded by a vowel and followed by a nasal consonant, it is dropped and the preceding vowel is lengthened.

- Szemerényi's law

- 1. In pre-Proto-Indo-European, the word-final fricatives *s and *h₂ are deleted in following a vowel–resonant sequence, followed by compensatory lengthening.[1] Some linguists include in the law a process where if the resulting sequence is *-ōn, the *n is also dropped, but others describe that deletion as a separate process.[38]

- 2. Also, broad Szemerényi's law; final Szemerényi's law. In pre-Proto-Indo-European, syllable-final fricatives are deleted following a vowel–consonant sequence, followed by compensatory lengthening. The process is blocked if the consonant preceding the fricative is in a cluster or if the following syllable begins with a consonant.[39][40]

- weather rule

- Laryngeals are lost in word-medial position preceding a stop followed by a resonant and a vowel. The law is named for its reflex in English, weather, which is derived from Proto-Indo-European *weh₁dʰrom 'weather'; the laryngeal *h₁ is deleted before the sequence *-dʰro- which comprises a stop, a resonant, and a vowel, respectively.[16] The law does not cause compensatory lengthening.[31]

- Weise's law

- Palatovelar consonants *ḱ *ǵ *ǵʰ are depalatalized when preceding *r. The law is named after the German linguist Oskar Weise who observed the results of the change in a 1881 essay on the topic.[41]

Extent of modern Indo-European languages in Europe and Asia

Albanian

[edit]- Rosenthall's law

- Within a morpheme, only one nasal–stop cluster is allowed; if more than one cluster exists in the underlying representation, any of these clusters created by morphophonological processes, such as epenthesis, are deleted.[42] Examples are found in the terms kuvend 'assembly' and mbrëmë 'last night', where the respective expected epenthetic forms *nguvend and *mbrëmbë reduced following this process.[43] The process has been likened to Lyman's law in Japanese and Grassmann's law in Ancient Greek and Sanskrit.[44] The law is named for the American linguist Samuel Rosenthall who first proposed the process in 2022.[42]

Balto-Slavic

[edit]- Lidén's law

- Word-initial *w in Proto-Indo-European is lost before non-syllabic *r and *l as the language developed into Proto-Balto-Slavic.[45] This process is named for the Swedish linguist Evald Lidén, who wrote about the process in 1899.[46] The process described by the law likely occurred after the development of Hirt's law, but before the syllabification of resonants. While it is possible that the law occurred after the syllabification of resonants and only affected non-syllabic resonants, Ranko Matasović finds this "improbable on phonetic grounds".[47]

- Hirt's law

- Also, Hirt–Illich-Svitych's law. If the syllable preceding the expected stressed syllable has a vowel immediately followed by a laryngeal, the stress is retracted to that syllable. The law was first proposed by the German philologist Hermann Hirt in 1895, but the original formulation was corrected in 1963 by the Soviet linguist Vladislav Illich-Svitych. Examples include comparisons of Lithuanian výras 'man, husband' and mótė 'mother' with Sanskrit वीरः vīráḥ 'man, hero' and माता mātā́ 'mother', respectively.[48] The law applies to the original PIE accent placement, but after leveling of PIE mobile-accented paradigms into end-stressed paradigms. It also applied before the epenthesis before syllabic sonorants.

- Pedersen's law

- In words with a Balto-Slavic mobile accent paradigm, the accent was retracted from a medial onto the initial syllable. In Proto-Slavic, a similar analogical change caused the retraction of the accent onto a preceding unaccented clitic, such as a preposition.

- Winter's law

- Short vowels with non-acute accents are lengthened before unaspirated voiced stops (*b, *d, *g, but not *ǵ). The newly lengthened vowel receives the acute accent.[49] The law is named after the German linguist Werner Winter who wrote his proposal in 1976, though it was not published until 1978.[50] Frederik Kortlandt has dated the law to the final years of the Balto-Slavic period.[51]

Baltic

[edit]- de Saussure's law

- (Lithuanian) Also, Saussure's law. If a non-acuted accented syllable is followed by an acuted syllable, the accent shifts forwards onto the acuted syllable. This split the Balto-Slavic fixed accent paradigm into Lithuanian paradigms 1 and 2, and the mobile accent paradigm into paradigms 3 and 4.

- Hjelmslev's law

- (Lithuanian) When a vowel receives an accent, it takes on the intonation of the following syllable.[52] The law is named for the Danish linguist Louis Hjelmslev, who proposed the process in his doctoral thesis in 1932.[53] Frederik Kortlandt states that, if the ictus retracts to a laryngealized vowel, the laryngeal is deleted and the result is a rising tone, but N. E. Collinge argues this is beyond the scope of process and that both Hjelmslev and de Saussure allow for a falling tone in their analyses.[54][55]

- Leskien's law

- (Lithuanian) If a word-final long vowel contains a falling accent, it is shortened. This process precedes Hjemslev's law, but is preceded by de Saussure's and Nieminen's laws.[56] The law is named for August Leskien, who first established the law in 1881.[57][58]

- Nieminen's law

- When the Proto-Baltic sequence *-ás is found word-finally, it is reduced to *-əs and loses its ability to carry stress. As a result, final stress is retracted to the penultimate syllable. This change explains the accentuation paradigm of o-stem nouns. Examples include báltas 'white' and var̃nas 'raven' from earlier *langás and *warnás, respectively. This is contrasted with mobile paradigms, where the accent is final, such as in galvà 'head' and žvėrìs 'beast'.[59] The process certainly precedes Leskien's law in Lithuanian, but has been suggested to go at least as far back as Proto-Baltic based on evidence from Old Prussian.[60] The law is named after the Finnish linguist Eino Nieminen who proposed the law in 1922.[59][61]

Slavic

[edit]

- Dybo's law

- Also, Dybo–Illich-Svitych's law. If a syllable was non-acute and accented, the accent was advanced onto the following syllable. The originally accented syllable retains its length. The change was prevented if the word had a mobile accent paradigm.

- fall of the weak yers

- Following the results of Havlík's law, weak yers were deleted. Examples are found in Old East Slavic, where earlier forms for the word 'prince' demonstrate a retained yer (кънѧзь kъnjazь), but later forms show it without (кнѧзь knjazь); the retained forms are dated to around 1075, while loss became widespread between the 1120s and 1210s.[62]

- Havlík's law

- In late Proto-Slavic, the vowels represented by *ь and *ъ, called yers, become "weak" – that is, subject to moraic shortening – in final position or if they are followed by a vowel other than another yer. A yer becomes "strong" if the following syllable contained a weak yer. In words with three successive syllables all containing yers, the final yer was weak, causing the penultimate syllable to be strong and the antepenultimate weak.[62] This process represents the first phase of the larger yer shift, where the second phase is known as the fall of the weak yers, where weak yers were deleted.[62]

- Ivšić's law

- Also, Stang's law;[d] Stang–Ivšić's law. Accented weak yers, as according to Havlík's law, lost their accent to the preceding syllable, which received a "neoacute" accent.

- law of open syllables

- Also, opening of syllables; tendency to rising sonority. Word- and syllable-final obstruents and obstruent clusters are deleted. Finals nasals are lost after short vowels and nasalized after long vowels.[63]

- Meillet's law

- In words with a mobile accent paradigm, if the first syllable is accented with a rising (acute) accent, it is converted into a falling (circumflex) accent.

- Shakhmatov's law

- (No longer widely accepted) Also, Šaxmatov's law. Slavic short falling (circumflex) accents shift leftward (i.e., to the preceding syllable).[64]

- Slavic first palatalization

- Also, first palatalization of velars; first regressive palatalization. When the velar sounds *k, *g, and *x occur before front vowels and *y, they undergo palatalization and become *č, *ž, and *š, respectively. If the velar follows a sibilant (i.e., *sk or *zg), the sibilant was backed to *šč and *ždž before the cluster was reduced in some dialects to *št and *žd.[65] The process was probably mediated by coronalization before a final assibilation. The time at which the process occurred is unknown but it must have occurred prior to the Migration Period and was completed sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries.[66]

- Slavic second palatalization

- Also, second palatalization of velars; second regressive palatalization. Following the monophthongization of Proto-Slavic *ai to *ě in open syllables and *i in closed syllables, velars became palatalized again. The process had different outcomes based on dialect: *k typically became *c and *g became either *dz or simply *z, but *x became *š in West Slavic, *xʲ in Novgorodian, and *s elsewhere. The process is estimated to have happened around the same time the West Slavs were migrating north of Carpathia and the Novgorodians were migrating to what is now northwestern Russia.[67] Like the first palatalization, the process occurred in several stages: palatal coarticulation, palatalization, and assibilation. It appears that Novgorodian only went through the first stage.[68] Clusters that had originally contained *ku̯ underwent palatalization in South Slavic and some East Slavic unless it was preceded by *s, but West Slavic and Novgorodian did not experience this palatalization at all.[69]

- Slavic third palatalization

- Also, progressive velar palatalization; palatalization of Baudouin de Courtenay. When Proto-Slavic *i, *i, or *in precede a velar, the velar is palatalized and then assibilated; *k and *g become *c and *dz, respectively, in all languages, with *dz undergoing further lenition to *z outside of Eastern South Slavic, Slovak, and Lechitic. In West Slavic, *x became *š, but *s or *sʲ in South and East Slavic.[70] Examples of this process include earlier *liːkad 'face', which became *liːca (whence Old Czech líce), and *mεːsinkaːd, the genitive singular form of 'moon', which became *mεːsĩːcaː (whence Old Polish miesięca).[70] The first stage of this process was in effect by the 6th and 7th centuries.[71]

- Stang's law

- If a word-final syllable was long falling (circumflex) accented, the accent was retracted onto the preceding syllable. The originally accented syllable is shortened, and the newly-accented syllable receives a "neoacute" accent. This change applied after Dybo's law, and often "undid" it by shifting the accent back again.

- Van Wijk's law

- Short vowels, except for yers (*ь, *ъ) and nasal vowels, are lengthened when preceded by a palatal consonant.[citation needed] Although Aleksey Shakhmatov was the first to suggest the process in 1898, the law is named for the Dutch linguist Nicolaas van Wijk, who published work on the process in 1916.[72][73]

- yer shift

- Also, jer shift; third Slavic vowel shift; fall of the yers. The yer vowels, *ь and *ъ, underwent two-part process followed by a third step that fractured the realization of the vowel qualities. First, yer vowels underwent an alternating pattern of weakening every other yer in a word beginning with weakening the final one; this first part of the shift is referred to as Havlík's law.[74] The process is a patterned form of compensatory lengthening.[75] Next, the weak yers were deleted, referred to as the fall of the weak yers.[62] Following this deletion, the remaining strong yers were thereby shifted to different vowel qualities in the various Slavic languages, which collectively are known as the vocalization of the yers.[76][77]

Celtic

[edit]- Joseph's law

- During the period between Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Celtic, when *e is followed by a resonant then by *a, the *e assimilates to *a. In other words, in the sequence *eRa, where *R signifies any resonant, *e becomes *a, thereby becoming *aRa.[78][79] Examples of this change include Proto-Celtic *taratro- 'drill' (whence Irish tarathar 'auger') from earlier *teratro-, derived from Proto-Indo-European terh₁tro- (whence Ancient Greek τέρετρον téretron 'borer, gimlet'). The law does not affect *ā and probably did not affect environments where the *a was word-final.[78] The law also appears to have affected words where the *a was formerly a laryngeal consonant in Proto-Indo-European, such as in Proto-Celtic *banatlo- 'broom plant' which may be derived from Proto-Indo-European *bʰenH-tlo from a root meaning 'to hit, to strike'.[80] The process was expanded in Welsh include environments where the resonant is followed by a nasal, explaining the vowel quality in Welsh words like sarnu 'to trample' but not Old Irish sernaid 'to arrange, to order', both from a Proto-Celtic *sternū/*starnati paradigm (from an older subjunctive Proto-Indo-European form *ster-nh₂-e/o, cognate with Latin sternō).[81] Similarly, another expansion of the process appears in both Brittonic and Gaulish, causing the assimilation of *o to *a in the resonant–vowel environment *oRa, thereby rendering *aRa. Compare Middle Welsh taran 'thunder' and Gaulish Taranis 'the Celtic god of thunder', which were affected by the expanded law, with Old Irish torann 'thunder', which was not.[82] The law is named after Lionel Joseph who covered the topic in 1982.[78][80]

- MacNeill's law

- (Old Irish) Also, MacNeill–O'Brien's law. Lenition of Old Irish n, r, and l is lost in final unstressed syllables even though they are etymologically expected to be lenited in that position.[83][84]

- McCone's law

- 1. Proto-Celtic *b and *u̯ become *β before *n word-internally. The latter change is rare, but occurs in words like Old Irish amnair 'maternal uncle' from Proto-Celtic *au̯n and omun 'fear' from *ɸoβnos. The law appears to have only occurred in contexts where there is no front vowel preceding the cluster, which accounts for apparent counterexamples like Welsh clun 'hip, haunch' from Proto-Indo-European *ḱlownis and Old Irish búan 'permanent' from *bʰewHnos, though some other etymologies account for different sources; the Welsh example may be a later borrowing from Latin clūnis, for example. The law shares a relationship to another Proto-Celtic sound change where *ɸ became *u̯ between either *a or *o and *n.[85]

- 2. (Old Irish) Unless the syllable is stressed, voiceless obstruents are voiced word-initially and word-finally.[86]

Germanic

[edit]- Cowgill's law of Germanic

- (Not fully accepted) When preceded by a sonorant and followed by *w, the PIE laryngeal *h₃ (and possibly also *h₂) appears as *k in Proto-Germanic after the application of Grimm's law.

- Germanic spirant law

- Also, Primärberühung. When a plosive is followed by any voiceless sound, normally *s or *t, it becomes a voiceless fricative and loses its labialization if present. A dental consonant followed by *s becomes *ss, and followed by *t becomes either *ss (in older inherited forms) or *st (in newer and productive forms).

- Grimm's law

- Also, first Germanic sound shift; first Germanic consonant shift; Rask's rule. The three series of Proto-Indo-European plosives undergo a chain shift. The first shift causes voiceless stops – *p, *t, *k, and *kʷ – to become the voiceless fricatives *f, *θ, *x, and *xʷ, respectively.[e] Next, the plain voiced stops – *b, *d, *g, and *gʷ – devoice and become *p, *t, *k, and *kʷ, respectively. Lastly, the aspirated voiced stops – *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ, and *gʷʰ – become voiced stops *b, *d, *g, and *gʷ, respectively.[92] This sound change is sometimes obfuscated in Old High German as a result of the High German consonant shift.[93] The process did not affect the second consonant in a cluster of two adjacent obstruents. Compare two versions of the Old Frisian word for 'throat': strot- and throt-. Both are derived from the Proto-Indo-European s-mobile root *(s)trewd-, the former including the s-mobile while the latter does not. In this example, the form with the s-mobile blocks the assibilation of the *t.[89] Several other exceptions are covered by Verner's law.[94] The Danish linguist Rasmus Rask is credited with first articulating the law in 1818, but its more common name is from German folklorist Jacob Grimm, who – after reading Rask's work – expanded on it and published it in the preface of his German grammar book in 1819 with a rewrite in 1822.[95]

- Holtzmann's law

- (North and East Germanic) Also, Verschärfung; sharpening; intensification. The geminated glides *jj and *ww are hardened into geminate plosives. In North Germanic, *jj becomes *ggj, while it became *ddj in East Germanic, *ww becomes *ggw in both.[96]

- Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law

- (Ingvaeonic languages) When followed by a fricative, /n/ is lost and the preceding vowel is lengthened and nasalized.

- Kluge's law

- (Not generally accepted) PIE plosives merge with a following *n and become geminate voiceless plosives in Germanic.

- Sievers's law

- Suffixal *j alternates with *ij depending on the syllable weight (length) of the preceding morpheme. *j appears after "light" or "short" morphemes, which consist of a single syllable ending in a short vowel and a single consonant. *ij appears elsewhere, including all morphemes with more than one syllable.

- Thurneysen's law

- (Gothic) Spirants in unaccented syllables changed their voiced–unvoiced quality based on the quality of the preceding consonant, whereby voiced spirants appear after unvoiced consonants and voiceless spirants appear after voiced consonants. Examples of both can be found in the dative singular forms, 𐌰𐌲𐌹𐍃𐌰 agisa 'fear' and 𐍂𐌹𐌵𐌹𐌶𐌰 riqiza 'darkness'.[97][f] In short, spirants are voiced when they are immediately preceded by a vowel without primary stress and the preceding consonant before the vowel is unvoiced. If the preceding consonant is a cluster where the second consonant is a liquid, the spirant remains unvoiced, but if the second consonant is a glide, it is voiced.[99] The process does not affect word-final spirants and the second element in a compound word where the simplex is stress-bearing. While some exceptions occur due to morphological leveling, there are at least seven words for which Thurneysen could not supply an explanation.[100] The law is named after the Swiss linguist Rudolf Thurneysen who posited the law in 1896 and published it in 1898.[101]

- Verner's law

- After the application of Grimm's law, when a voiceless fricative is preceded by an unaccented syllable, it is voiced (*f, *þ, *h, *hʷ, *s > *b, *d, *g, *gʷ, *z). Following this, the mobile PIE accent is lost and all words receive stress on the first syllable.

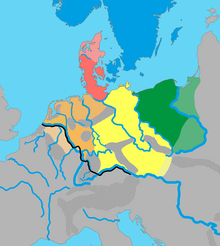

North Sea Germanic, or Ingvaeonic

Weser–Rhine Germanic, or Istvaeonic

Elbe Germanic, or Irminonic

Greek

[edit]

- Bartoli's law

- Also, Bàrtoli's law. In short–long metrical feet where oxytone stress is expected, the syllable becomes paroxytone before a word boundary. The law only occurs in anapestic (short–short–long) and cretic (long–short–long) contexts. An example of this process can be seen in Ancient Greek θυγάτηρ thygátēr 'daughter', in its nominative singular form, when contrasted with its accusative singular form θυγατέρα thygatéra and with the Sanskrit nominative singular दुहिता duhitā́ 'daughter'. While some exceptions can be attributed to analogical change, there are still some unexplained exceptions.[102] The law is named after the Italian linguist Matteo Bartoli, whose 1930 publication contrasted Sanskrit oxytone words with their Ancient Greek paroxytone cognates.[103]

- Cowgill's law of Greek

- Whenever Proto-Indo-European *o occurs between a resonant and a labial, it becomes Greek υ y.[104][105] The resonant and the labial can be on either side of the *o and produce the same output. Examples of a resonant followed by *o followed by a labial include (νύξ nýx 'night' from *nokʷt- (whence also Latin nox 'night'). This law is preceded by laryngeal coloring, meaning that Proto-Indo-European sequences of *h₁o, *h₃o, and *h₃e are also accounted for in the law, as are cases in which the zero-grade form was vocalized, such as in στόρνυμεν stórnymen 'we smooth out' from Proto-Indo-European *str̥-n-h̥₃-, showing the nasal infix. Some later sound changes obfuscate the law, but there is evidence to show that the sound change still occurred. For example, Proto-Indo-European *nomn̥ 'name' gave way to Proto-Greek *onuma. Although in Attic Greek the form became ὄνομα ónoma, the expected form ὄνυμα ónyma is found in both Doric and Aeolic Greek; the expected form is also found in derivatives such as ἀνώνυμος anṓnymos 'nameless, inglorious'.[104]

- Vendryes's law

- Also, Vendryès's law. Any perispomenon with a short vowel in the antepenultimate becomes proparoxytone in Attic. The law is named after the French linguist Joseph Vendryes.[106]

- Wheeler's law

- Also, law of dactylic retraction. Oxytone words in Proto-Indo-European become paroxytone in Ancient Greek if the word has a dactylic ending; in other words, the stress in dactylic words moved from the final syllable to the penultimate syllable.[106][107] The law counts endings such as ον -on, ος -os, and οι -oi as short. Examples of this tonic retraction include cognate pairs like ποικίλος poikílos 'variegated, complex', with a paroxytone, and Vedic Sanskrit पेशलः peśaláḥ. The law is named after the American philologist Benjamin Ide Wheeler who published work on the topic in 1885.[106][107]

Indo-Iranian

[edit]- Brugmann's law

- When it is an ablaut alternant of *e, the vowel *o is lengthened and (after merging) becomes *ā when it stands at the end of a syllable.

- Fortunatov's law

- (Sanskrit) When Proto-Indo-European *l precedes a dental consonant, the latter becomes a retroflex consonant and the *l is deleted. Examples include जठर jaṭhára 'belly', which is derived from Proto-Indo-European *ǵelt-, and कुठार kuṭāra 'ax', derived from *kult-. The law is named after the Russian linguist Filipp Fortunatov.[108]

- law of the palatals

- Also, Palatalgesetz. Proto-Indo-European *e palatalizes velar stops and becomes Proto-Indo-Iranian *a.[109] The process is preceded by the delabialization of the labiovelar consonants.[110][111] Although several linguists have attempted to identify the originator of the law and several have declared a supposed originator, no consensus has been reached.[112] According to N. E. Collinge, it appears that six different linguists – Hermann Collitz, Ferdinand de Saussure, Johannes Schmidt, Esaias Tegnér Jr., Vilhelm Thomsen, and Karl Verner – discovered the law "roughly simultaneously" and "in entire independence" from one another.[113]

Italic

[edit]

- Exon's law

- In a word with four or more syllables, if the second and third syllable are short, then the vowel of the second syllable is syncopated, though it may be restored by analogy.

- Lachmann's law

- When a short vowel is followed by an underlyingly voiced stop followed by a voiceless stop, it is lengthened. The process explains the differences between verbal forms, such as agō 'I drive' and cadō 'I fall', and their respective derivatives, such as āctus 'made, done' and cāsus 'a fall'.[115] Although the law was popularized by Paul Kiparsky,[115] it is named for the German classicist Karl Lachmann who wrote about the process in 1850.[116] It is unclear if the law applied to the whole Italic language family, but it applied at least to Latin.[115]

- pius law

- Also, Thurneysen's law. The Proto-Italic diphthong *ūy, derived from a Proto-Indo-European sequence of *u followed by a laryngeal and *i, is fronted to *īy. Examples include Oscan piíhiúí 'pious (dative singular)' and Latin pius 'pious', both from Proto-Italic *pīyo- derived from Proto-Indo-European *puh₂yo- 'pure'.[117] The root is shared with the Latin pūrus 'pure', derived from Proto-Indo-European *puH-ro- 'clean', which did not undergo this change.[118] Warren Cowgill argued that this law also occurred in Celtic in attempting to unify both Italic and Celtic into a double-jointed Italo-Celtic subfamily.[119]

- Thurneysen–Havet's law

- The Proto-Italic diphthong *ow becomes *aw before a vowel.[117][120] This process precedes the Proto-Italic rounding of the diphthong *ew to *ow. Examples include Latin caueō 'I am weary of', derived from Proto-Indo-European *kowh₁-eyo- (whence Ancient Greek κοέω koéō 'I am aware').[117] There appears to be some variation based on Roman social register and the process may also affect the inverted sequence *wo. For example, the Latin term vacuus exists alongside vocīuus in the work of some comedians, including in Casina, a play written by Plautus. The law is named for the Swiss linguist Rudolf Thurneysen and the French classicist Louis Havet, who appear to have developed the concept largely independently of each other in 1884 and 1885, respectively.[121]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Trask credits Collinge with naming the process, but in the work cited, Collinge states that others have "fashionably called" it by this name prior to publication.[4]

- ^ Initial /h/ in Ancient Greek is represented by the diacritical mark /◌̔/ appearing over the following vowel.[20] For further discussion, see Rough breathing.

- ^ The verb is attested only in its present participle form ἐρέπτόμενοι ereptómenoi.[24] The term is attested in the Odyssey where the men pluck and eat the lotus.[25]

- ^ Not to be confused with § Stang's law or § Stang's law (Slavic).

- ^ Different authors prefer different symbols to represent the Proto-Germanic fricative sounds produced by Grimm's law. Collinge 1985 prefers the symbol *þ – derived from the rune thorn, used in the alphabets of some Germanic languages to represent dental fricatives[87] – in lieu of *θ, but the sound both symbols represent are equivalent.[88] Stiles 2018 uses thorn as well, but replaces *x and *xʷ with *χ and *χʷ,[89] but allows *h and *hʷ as acceptable alternatives.[90] Clackson 2007 also prefers the *h convention.[91] This glossary follows the convention used by Trask 2000.[92]

- ^ The nominative singular forms are 𐌰𐌲𐌹𐍃 agis and 𐍂𐌹𐌵𐌹𐍃 riqis, respectively.[98]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Byrd 2015, p. 20.

- ^ Byrd 2018, p. 2060.

- ^ a b c d Trask 2000, p. 29.

- ^ a b Collinge 1985, p. 47.

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 47, 50.

- ^

- Ringe 2006, p. 20: "It is possible, but not certain, that the rule was inhereited from PIE."

- Collinge 1985, p. 8: "Some take the law to be of PIE date, even so. Kuryłowicz regularly opines so [...] Bartholomae himself suggested a wider domain [...] So does Szemerényi [...]"

- Lubotsky 2018, p. 1879: "Bartholomae's Law, which is most probably of IE date [...]"

- Beekes 2011, p. 130: "But the evidence in favour of a PIE date is not very convincing. Worth considering, however, is the explanation of suffix variants like *-tro-/*-dʰro- [where] *-dʰ- would have arisen from *-t- after an aspirate [...]".

- Fortson 2010, p. 69: "Bartholomae's law [...] is reflected most clearly in Indo-Iranian; whether it was of PIE date is controversial."

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 7.

- ^ Byrd 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Ringe 2006, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b Fortson 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b Ringe 2006, p. 92.

- ^

- For the Proto-Germanic form, see Ringe 2006, p. 92 and Skeat 1879, p. 711. Skeat uses older terminology; here, "Teuton" signifies what is now known as Proto-Germanic.

- For the Latin and Old Latin etymologies, see Sihler 1995, p. 39 and Skeat 1879, p. 711.

- For the Old English etymology, see Ringe 2006, p. 92, Skeat 1879, p. 711, and Sihler 1995, p. 39.

- For the relationship of Modern English tongue to Proto-Germanic *tungōn-, see Skeat 1879, p. 711.

- ^ a b Meiser 2018, p. 746.

- ^ a b Matasović 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Matasović 2009, pp. 338, 349.

- ^ a b c Byrd 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Matasović 2009, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Trask 2000, p. 143.

- ^ Beekes 2011, p. 100.

- ^ "rough breathing". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Langendoen 1966, p. 7.

- ^ Eskes 2020, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Eskes 2020, p. 5–6.

- ^ Liddell et al. 1940, p. 685.

- ^ Autenrieth 1887, p. 127.

- ^ Garnier, Hattat & Sagot 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Bičovský 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Eskes 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Eskes 2020, p. 22.

- ^

- Byrd 2015, p. 26

- Vine 2018, p. 756

- Hackstein 2018, p. 1327

- ^ a b Byrd 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Kölligan 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Hackstein 2018, p. 1327.

- ^ Byrd 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Beekes 1969, pp. 243–245.

- ^ a b c Byrd 2015, pp. 25, 205–206.

- ^ Matasović 2009, pp. 150–151.

- ^

- For the deletion of final *n as part of the law, see Ringe 2006, pp. 20–21 and Vaux 2002, pp. 2–3.

- For the deletion as a separate process, see Byrd 2015, pp. 20–21 and Fortson 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Sandell & Byrd 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Byrd 2015, p. 29.

- ^ Kloekhorst 2011, p. 262.

- ^ a b Dedvukaj & Gehringer 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Dedvukaj & Gehringer 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Dedvukaj & Gehringer 2023, p. 12–13.

- ^

- Collins 2018, p. 1437

- Matasović 2005, p. 4

- Pronk 2022, p. 271

- ^ Collins 2018, pp. 1518, 1532.

- ^ Matasović 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Kortlandt 1977, p. 321.

- ^

- For the exception of *ǵ, see Trask 2000, p. 367

- For concept in general, see Collinge 1985, p. 225

- For discussion without reference to the acute accent, see Beekes 2011, p. 129 and Clackson 2007, pp. 46–47

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 225.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 226.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 89–91.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 89.

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Kortlandt 1977, p. 327.

- ^

- For relationship to Hjemslev's law, see Collinge 1985, p. 115–116.

- For the relationship to de Saussure's and Nieminen's laws, see Kortlandt 1977, p. 328.

- For the relationship to Nieminen's law, see Villanueva Svensson 2021, p. 7.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 115.

- ^ Kortlandt 1977, p. 328.

- ^ a b Villanueva Svensson 2021, p. 5.

- ^ Villanueva Svensson 2021, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b c d Collins 2018, p. 1492.

- ^ Collins 2018, pp. 1440–1441.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 153–154.

- ^ Collins 2018, pp. 1442–1443.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1443.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1462.

- ^ Collins 2018, pp. 1462–1463.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1464.

- ^ a b Collins 2018, p. 1465.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1466.

- ^ Babik 2017, p. 227.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 197.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1492–1493.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1496.

- ^ Collins 2018, p. 1493–1494.

- ^ Trask 2000, p. 343.

- ^ a b c Jørgensen 2022, p. 139.

- ^ Zair 2012, p. 156.

- ^ a b Matasović 2009, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Jørgensen 2022, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Jørgensen 2022, p. 147.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 235.

- ^ Oliver 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Stifter 2018, p. 1193–1194.

- ^ Stifter 2018, p. 1200.

- ^ "thorn". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 66.

- ^ a b Stiles 2018, p. 890.

- ^ Stiles 2018, p. 889.

- ^ Clackson 2007, p. 32.

- ^ a b Trask 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 65.

- ^ Stiles 2018, pp. 890–891.

- ^

- Trask 2000, p. 122

- Collinge 1985, p. 64

- Stiles 2018, p. 890

- ^ Stiles 2018, p. 900.

- ^ Stiles 2018, p. 892.

- ^

- For agis, see Lehmann 1986, p. 10.

- For riqis, see Lehmann 1986, p. 286

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 184.

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 184–185.

- ^

- Collinge 1985, pp. 183–184

- Trask 2000, p. 344

- Stiles 2018, p. 892

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 230.

- ^ a b Sihler 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Matasović 2009, p. 333.

- ^ a b c Collinge 1985, p. 221.

- ^ a b Meier-Brügger, Fritz & Mayrhofer 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 41.

- ^

- Clackson 2007, p. 32.

- Collinge 1985, p. 135.

- Meier-Brügger, Fritz & Mayrhofer 2003, p. 78–79.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 135.

- ^ Meier-Brügger, Fritz & Mayrhofer 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 135–136.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 135–139.

- ^ Maras 2012, pp. 1, 20.

- ^ a b c Jasanoff 2004, p. 405.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Meiser 2018, p. 745.

- ^

- For conference with pūrus, see Meiser 2018, p. 745.

- For the etymology of pūrus, see de Vaan 2008, pp. 500–501.

- ^ Ringe 2018, p. 64.

- ^ Collinge 1985, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Collinge 1985, p. 193.

Sources

[edit]- Autenrieth, Georg (1887) [1873]. Wörterbuch zu den Homerischen Gedichten [A Homeric Dictionary, for Schools and Colleges]. Translated by Keep, Robert P. Harper & Brothers.

- Babik, Zbigniew (2017). "The hypothesis of a postpositional compensatory lengthening (so-called van Wijk's law) vs. the relative chronology of Common Slavic phonological developments – in search of inconsistencies". Baltistica. 52 (2). doi:10.15388/baltistica.52.2.2320. ISSN 2345-0045.

- Beekes, R. S. P. (1969). van Schooneveld, C. H. (ed.). The Development of the Proto-Indo-European Laryngeals in Greek. Janua Linguarum: Studia Memoriae Nicholai van Wijk Dedicata. Vol. 42. The Hague: Mouton – via Internet Archive.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (18 October 2011). de Vaan, Michiel (ed.). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8500-3. OCLC 730054595 – via Internet Archive.

- Bičovský, Jan (2021). "The phonetics of PIE *d I: typological considerations". Linguistica Brunensia. 69 (2). Masaryk University: 5–21. doi:10.5817/LB2021-2-1. ISSN 2336-4440.

- Byrd, Andrew Miles (2015). The Indo-European Syllable. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29302-1.

- Clackson, James (18 October 2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36609-3. OCLC 123113761.

- Collinge, N. E. (1985). The Laws of Indo-European. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 35. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-8638-3.

- Dedvukaj, Lindon; Gehringer, Patrick (2023-04-27). "Morphological and phonological origins of Albanian nasals and its parallels with other laws". Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America. 8 (1): 5508. doi:10.3765/plsa.v8i1.5508. ISSN 2473-8689. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- de Vaan, Michiel (2008). Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Vol. 7. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16797-1. OCLC 225873936.

- Eskes, Pascale (July 2020). The Kortlandt Effect (Master's thesis). Leiden: University of Leiden.

- Fortson IV, Benjamin W. (2010). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8895-1. OCLC 276406248.

- Garnier, Romain; Hattat, Philippe; Sagot, Benoît (2019). What is Old is New again: PIE Secondary Roots with Fossilised Preverbs (Speech). Invited talk at the University of Leiden. Leiden. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- Jasanoff, Jay H. (2004), "Plus ça change...: Lachmann's Law in Latin" (PDF), in J. H. W. Penney (ed.), Indo-European Perspectives: Studies in Honour of Anna Morpurgo Davies, Oxford University Press, pp. 405–416, ISBN 978-0-19-925892-5

- Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias, eds. (11 June 2018). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-054052-9.

- Ringe, Don. "6. Indo-European dialectology". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 62–75.

- Meiser, Gerhard. "47. The phonology of Italic". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 743–751.

- Vine, Brent. "48. The morphology of Italic". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 751–804.

- Stiles, Patrick V. "54. The phonology of Germanic". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 888–912.

- Stifter, David. "68. The phonology of Celtic". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 1188–1202.

- Hackstein, Olav. "75. The phonology of Tocharian". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 1304–1335.

- Collins, Daniel. "81. The phonology of Slavic". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 1414–1538.

- Lubotsky, Alexander. "110. The phonology of Proto-Indo-Iranian". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 1875–1888.

- Byrd, Andrew Miles. "121. The phonology of Proto-Indo-European". In Klein, Joseph & Fritz (2018), pp. 2057–2079.

- Kloekhorst, Alwin (2011) [2008]. Written at Salzburg. "Weise's Law: Depalatalization of Palatovelars before *r in Sanskrit" (PDF). Wiesbaden, Germany: Indo-European Studies and Linguistics in Dialog: Acts of the XIIIth Conference of the Society of Indo-European Studies.

- Kölligan, Daniel (2015). "A Note on Proto-Norse ek and Kuiper's law" (PDF). International Journal of Diachronic Linguistics and Linguistic Reconstruction. 12 (2). Munich: 83–87. ISSN 1614-5291. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (1977). "Historical laws of Baltic accentuation". Baltistica. 13 (2). doi:10.15388/baltistica.13.2.1129. hdl:1887/1854. ISSN 2345-0045.

- Langendoen, D. Terence (1966). "A Restriction on Grassmann's Law in Greek". Language. 42 (1). Linguistic Society of America: 7–9. doi:10.2307/411596. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 411596. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- Lehmann, Winfred P. (1986). A Gothic Etymological Dictionary. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-08176-3 – via Internet Archive.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; Jones, Henry Stuart; McKenzie, Roderick, eds. (1940) [1843]. A Greek–English Lexion (Ninth ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press – via Internet Archive.

- Maras, Daniele Federico (2012). "Scientists declare the Fibula Prenestina and its inscription to be genuine "beyond any reasonable doubt"" (PDF). Etruscan News. 14. Institute for Etruscan and Italic Studies: 1, 20.

- Matasović, Ranko (29 December 2005). "Toward a relative chronology of the earliest Baltic and Slavic sound changes". Baltistica. 40 (2): 1–10. doi:10.15388/baltistica.40.2.674. ISSN 2345-0045.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17336-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Meier-Brügger, Michael; Fritz, Matthias; Mayrhofer, Manfred (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. Translated by Gertmenian, Charles. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017433-2.

- Olander, Thomas, ed. (22 September 2022). The Indo-European Language Family: A Phylogenetic Perspective. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108758666. ISBN 978-1-108-75866-6.

- Jørgensen, Anders Richardt. "9. Celtic". In Olander (2022), pp. 135–151.

- Pronk, Tijmen. "15. Balto-Slavic". In Olander (2022), pp. 269–292.

- Oliver, Lisi (1992). "The Origin of Irish Resonant Geminates and MacNeill's Law". Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. 12. Department of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard University: 93–109. ISSN 1545-0155. JSTOR 20557241. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- Probert, Philomen; Willi, Andreas, eds. (10 May 2012). Laws and Rules in Indo-European. Oxford: Clarendon Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199609925.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960992-5.+

- Zair, Nicholas. "Schrijver's rules for British and Proto‐Celtic *‐ou̯‐ and *‐uu̯‐ before a vowel". In Probert & Willi (2012), pp. 147–160.

- Ringe, Donald (31 August 2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (PDF). A Linguistic History of English. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928413-9. OCLC 69241395.

- Sandell, Ryan; Byrd, Andrew Miles (6 June 2014). In Defense of Szemerényi's Law. East Coast Indo-European Conference. Blacksburg, Virginia.

- Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537336-3 – via Internet Archive.

- Skeat, Walter William (1879). An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-863104-0 – via Hathi Trust.

- Trask, R. L. (2000). Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-7331-6. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctvxcrt50.

- Vaux, Bert (2002). Diebold, Richard (ed.). "Stang's Law and Szemerenyi's Law in nonlinear phonology". Journal of Indo-European Studies. Monograph Series (41). Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man: 317–327. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- Villanueva Svensson, Miguel [in Lithuanian] (2021-11-27). "Nieminen's law revisited". Baltistica. 56 (1): 5–18. doi:10.15388/baltistica.56.1.2427. ISSN 2345-0045.

Further reading

[edit]- Kortlandt, Frederik (2019). "Van Wijk's law and questions of relative chronology". Baltistica. 54 (1): 29–34. doi:10.15388/baltistica.54.1.2373. ISSN 2345-0045. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- Pronk, Tijmen (2016). "Stang's law in Baltic, Greek and Indo-Iranian". Baltistica. 51 (1): 19–35. doi:10.15388/baltistica.51.1.2267. ISSN 2345-0045. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- Woodard, Roger D., ed. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8. OCLC 166382267.

- Yamazaki, Yoko (6 March 2012). Monosyllabic Circumflexion in Lithuanian – with an investigation of some dialectal forms (PDF). Conference on Indo-European Linguistics. Kyoto University.