User:Viva el ROC China/sandbox

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (May 2013) |

| Dungan revolt | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yakub Bek | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

Kashgaria (Kokandi Uzbek Andijani and Turki Rebels)

Supported by:

| Hui Muslim rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Zuo Zongtang Wang Dagui Dong Fuxiang Ma Zhan'ao Ma Anliang Ma Qianling Ma Haiyan Dolongga |

Yakub Beg Hsu Hsuehkung |

Ma Hualong T'o Ming | ||||||

|

Bai Yanhu Muhammed Ayub | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| Hunan Army, 120,000 Zuo Zongtang army and Loyalist Khafiya Chinese Muslim troops | Andijani Uzbek troops and Afghan volunteers, Han Chinese and Hui forcibly drafted into Yaqub's army, and separate Han Chinese militia | Rebel Jahriyya Chinese Muslim and some Rebel Han Chinese | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Muslim death in Shanxi alone could be as high as 4,000,000 during the Tong Zhi Muslim Revolt (同治回乱) of 1862 | Total death: 8,000,000 -12,000,000, including civilians and soldiers | |||||||

The Dungan Revolt (simplified Chinese: 同治新疆回变; traditional Chinese: 同治新疆回變; pinyin: Tóng Zhì Xīn Jiāng Huí Biàn) was mainly an ethnic war in 19th-century China. It is also known as the Hui Minorities War. The term is sometimes used to include the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan which occurred during the same period. However, in this article, this term is strictly an uprising by members of the Muslim Hui and other Muslim ethnic groups in China's Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia provinces, as well as in Xinjiang, between 1862 and 1877. The revolt was set off over a pricing dispute involving bamboo poles which a Han was selling to a Hui, who did not pay the amount the Han merchant demanded.

The uprising was chaotic and often involved warring factions of bands and military leaders with no common cause or single specific goal or purpose on the western bank of the Yellow River (Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia (excluding Xinjiang province)). A common misconception is that the revolt was directed against the Qing Dynasty, but actually there is no evidence showing that they intended to attack the capital, Beijing, or overthrow the whole government system of Qing Empire Qing Dynasty. When the rebellion failed, mass emigration of the Dungan people into Imperial Russia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan ensued.

Names

[edit]The Dungan people in this article referred to Hui people, which are a predominantly Muslim ethnic group in China. They are also called "Chinese Muslims" sometime. They are not to be confused with "Turkestanis", or "Turkic" people in this article, who are known as Uyghur people, Kazakh people, Kyrgyz people, Tatars, Uzbeks...etc.

Anachronisms

[edit]The ethnic group now known as Uyghur people was not known by the name "Uyghur" before the 20th century. The Uzbeks of Yaqub Beg were called Andijanis or Kokandis, while the Uyghurs in the Tarim Basin were called "Turki", and Uyghur immigrants from the Tarim Basin to Ili were called "Taranchi". The modern name "Uyghur" was assigned to this ethnic group by the Soviet Union in 1921 at a conference in Tashkent,and the name Uyghur was taken from the old "Uyghur Khaganate". Sources from the time period of the Dungan revolt therefore make no mentions of Uyghurs.

Although the ethnic group called the Hui were called by that name in Chinese, Europeans commonly referred to them as "Dungan" or "Tungan" during the Dungan revolt.

Rebellion in Gansu and Shaanxi

[edit]| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

|

|

|

Background

[edit]The Dungan Revolt by the Hui was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than the mistaken assumption that it was entirely due to religion that the rebellions broke out.[1]

In the Qianlong era, scholar Wei Shu (魏塾) commented on Jiangtong's (江统) essay Xironglun (徙戎论) that if the Muslims didn't migrate out, they were going to be like the Five Hu 五胡, who overthrew the Western Jin, which resulted in ethnic (not religious) conflict between the Wu Hu and Han Chinese. During Qianlong's reign there were clashes between the Qing authorities and the Jahriyya Sufi sect, but not with the majority non Sufi Sunnis or the Khafiyya Sufis.

Chinese Muslims had been travelling to West Asia for many years prior to the Hui Minorities' War. In the 18th century, several prominent Muslim clerics from Gansu studied in Mecca and Yemen under the Naqshbandi Sufi teachers. Two different forms of Sufism were brought back to Northwest China by two charismatic Hui sheikhs: Khafiya (also spelled Khafiyya or Khufiyah; Chinese: 虎夫耶, Hǔfūyē), associated with the name of Ma Laichi (马来迟, 1681–1766), and a more radical Jahriyya (also spelled Jahriya, Jahariyya, Jahariyah, etc.; Chinese: 哲赫林耶, Zhéhèlínyē, or 哲合忍耶, Zhéhérěnyē), founded by Ma Mingxin (马明新 or 马明心, 1719(?)-1781). These coexisted with the more traditional, non-Sufi Sunni practices, centred around local mosques and known as gedimu (qadim, 格底目 or 格迪目). The Khafiya school, as well as non-Sufi gedimu tradition, both tolerated by the Qing authorities, were referred to "Old Teaching" (老教). While Jahriya, viewed as suspect, became known as the "New Teaching" (新教).

Disagreements between the adherents of Khafiya and Jahriya, as well as perceived mismanagement, corruption, and anti-Sufi attitudes of the Qing officials resulted in uprisings by Hui and Salar followers of the New Teaching in 1781 and 1783. However, they were promptly suppressed. Hostility between different groups of Sufis contributed to the violent atmosphere before the Dungan revolt from 1862 to 1877.[2]

Course of the rebellion

[edit]As the Taiping troops approached south-eastern Shaanxi in the spring of 1862, the local Han Chinese, encouraged by the Qing government, formed tuanlian (trad. 團練, simplified 团练) militias to defend the region against the Taiping. Afraid of the armed Han, the Muslims formed their own militia units as a response.

According to modern researchers,[3] the Muslim rebellion began in 1862 not as a planned uprising, but as a coalescence of many local brawls and riots triggered by trivial causes. In addition, there were false rumors spread that the Hui Muslims were aiding the Taiping Rebellion. However, it is also said that the Hui Ma Hsiao-shih claimed that the Shaanxi Muslim rebellion was connected to the Taiping.[4]

Many Green Standard troops of the Imperial army were Hui. One of these brawls and riots was initiated when a fight was triggered over the price of bamboo poles which a Han was selling to a Hui. This led to a massacre of Hui in multiple villages when they refused to agree to the price of the poles. During the massacre, a lot of innocent people were killed. Thereafter, Hui people attacked Han people and other Hui people who did not join them in revolt as a response. It was this pricing dispute over bamboo poles which set off the full scale revolt. An Manchu official noted that there were many non rebellious Muslims who were loyal citizens, and warned the Qing Empire court that exterminating all Muslims would force them to support the rebels and make the situation even worse. He said, "Among the Muslims, there are certainly evil ones, but doubtless there are also numerous peaceful, law-abiding people. If we decide to destroy them all, we are driving the good ones to join the rebels, and create for ourselves, an awesome, endless job of killing the Muslims".[5][6]

Given that the prestige of the Qing Dynasty was being low and its armies were busy elsewhere, the rebellion that began in the spring of 1862 in the Wei River valley was able to spread rapidly throughout the south-eastern Shaanxi. By late June 1862, the organized Muslim fighter bands were able to besiege Xi'an, which was not relieved by the Qing general Dolongga (Chinese: 多隆阿, Duo Long-a) until the fall of 1863. Dolongga was a Manchu bannerman and he was given command over the Army in Hunan province. His leadership over the Hunan forces defeated the Muslim rebels and totally destroyed their position in Shaanxi province, expelling them to Gansu. Dolongga was killed in action on March 1864 by Taiping rebels in Shaanxi.[7]

The Governor General of the region named En-lin advised the Imperial government not to alienate Muslims, and officially made clear that there was to be no mistreatment or discrimination of Muslims,resulting in a "policy of reconciliation" being implemented. Muslim rebels tried to seize Lingzhou (nowadays Lingwu)and Guyuan in several attacks. False rumors voiced by Muslims that the government was going to kill Muslims led to these battles.[8]

A vast number of Muslim refugees from Shaanxi fled to Gansu. Some of them formed the "Eighteen Great Battalions" in eastern Gansu, intending to fight back to their homes in Shaanxi.While the Hui rebels took over Gansu and Shaanxi, Yaqub Beg, who had fled from Kokand Khanate in 1865 or 1866 after losing Tashkent to the Russians, declared himself as the ruler of Kashgar and soon managed to control the entire Xinjiang.

In 1867, the Qing government sent one of their most capable generals Zuo Zongtang, who was instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, to Shaanxi. Zuo's approach was to pacify the region by promoting agriculture, especially cotton and grain, as well as supporting orthodox Confucian education. Due to the poverty of the region, Zuo had to rely on financial support from outside the Northwestern China.

Zuo Zongtang called on the government to 'support the armies in the North-West with the resources of the South-East', and arranged the finances of the planned expedition to conquer Gansu by obtaining loans worth millions of taels from foreign banks in the south-eastern provinces. What the foreign banks obtained from their ports through the Chinese customs would repay the loans later. Zuo also arranged for massive amounts of supplies to be available before he would go on the offensive.[9] 10,000 of the old Hunan Army troops which were commanded by Zeng Guofan were sent by him, let by Liu Songshan to Shaanxi to help General Zuo. Zuo Zongtang had already raised a 55,000 man army from Hunan before he began the final push to reconquer Gansu from the Dungan rebels. They participated along with other regional armies (the Sichuan, Anhui, and Henan armies also joined the battle.[10]

Zuo's forces consisted of the Hunan Army, Sichuan Army, Anhui Army, and Henan Army, along with thousands of cavalry. The Hunan soldiers were expert marksmen with guns and battle field maneuvers. They were under the command of General Liu Songshan.[11] Western military drill was experimented with, but Zuo decided to abandon it. The troops practiced "twice a day for ten days" with their western made guns.[12]

The Lanzhou Arsenal was established in 1872 by Zuo Zongtang during the revolt and it was staffed by Cantonese.[13] The Cantonese officer in charge of the arsenal was Lai Ch'ang, who was skilled at artillery.[14] It manufactured 'steel rifle-barrelled breachloaders' and provided munitions for artillery and guns.[15] The Muslim Jahriyya leader Ma Hualong controlled a massive Muslim trading network with many Muslim traders, having control over trade routes to multiple cities over different kinds of terrain. He monopolized trade in the area and used his wealth to purchase guns. Zuo Zongtang was suspicious of Ma's intentions, thinking that he wanted to seize control over the entire Mongolia.[16] Liu Songshan died in combat during an offensive against rebel forts protected by the difficult terrain, which numbered in the hundreds. Liu Jintang, his nephew, took over his command. A temporary lull in the offensive set in.[17] After suppressing the rebellion in Shaanxi and building up enough grain reserves to feed his army, Zuo attacked the paramount Muslim leader Ma Hualong (馬化龍). General Liu Jintang led the siege, bombarding the town over its walls with shells. The people of the town had to cannibalize dead bodies and grass roots to survive.[18] Zuo's troops reached Ma's stronghold, Jinjibao (Chinese: 金积堡, Jinji Bao, i.e. Jinji Fortress) in what was then north-eastern Gansu[19][20][21] in September 1870, bringing Krupp siege guns with him. Zuo and Lai Ch'ang themselves directed the artillery fire against the city. Mines were also utilized.[22] After a sixteen-month siege, Ma Hualong was forced to surrender in January 1871. Zuo sentenced Ma and over eighty of his officials to death by slicing. Thousands of Muslims were exiled to other parts of China.

Zuo's next target was Hezhou (now known as Linxia), the main center for the Hui people west of Lanzhou and a key point on the trade route between Gansu and Tibet. Hezhou was defended by the Hui forces of Ma Zhan'ao (马占鳌). As a pragmatic member of the Khafiya (Old Teaching) sect, he was ready to explore avenues for peaceful coexistence with the Qing Government. When the revolt broke out, Ma Zhan'ao escorted Han Chinese to safety in Yixin, and did not attempt to conquer more territory during the rebellion.[23] After successfully repulsing Zuo Zongtang's initial assault in 1872 and inflicting heavy losses on Zuo's army, he offered to surrender his stronghold to the empire, and his assistance to Qing Dynasty for the duration of the war. He managed to preserve his Dungan community with his diplomatic skill. While Zuo Zongtang pacified other areas by exiling the local Muslims (with the policy of "washing off the Muslims" (Chinese: 洗回; pinyin: Xǐ Huí) approach that had been long advocated by some officials), in Hezhou, the non-Muslim Han were the ones Zuo chose to relocate as a reward for Ma Zhan'ao and his Muslim troops helping Qing crush Muslim rebels. Hezhou (Linxia) remains heavily Muslim to this day, achieving the status of Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture under the PRC. Other Dungan generals like Ma Qianling and Ma Haiyan also defected to Qing Government along with Ma Zhan'ao. Ma Zhanao's son Ma Anliang also defected, and their Dungan forces assisted Zuo Zongtang's Qing forces in crushing the rebel dungans. Dong Fuxiang also defected to the Qing dynasty side, along with Ma Zhanao.[24] He was in no sense a fanatical Muslim or even interested in rebellion, he merely gained support during the chaos and fought, just as many others did. He joined the Qing army of Zuo Zongtang in exchanged for a Mandarinate. He acquired estates which were large.[25]

Reinforced by the Dungan people in Hezhou , Zuo Zongtang planned advance westward, along the Hexi Corridor toward Xinjiang. However, he felt it necessary to first secure his left flank by taking Xining, which not only had a large Muslim community of its own, but also sheltered many of the refugees from Shaanxi. Xining fell after a three-month siege in late 1872. Its commander Ma Guiyuan was captured, and defenders were killed by the thousands.[14] The Muslim population of Xining was spared, however; the Shaanxi refugees sheltered there were resettled to arable land in eastern and southern Gansu, isolated from other Muslim areas.

Despite repeated offers of amnesty, many Muslims continued to resist at Suzhou (Jiuquan), their last stronghold in Hexi Corridor in west Gansu. The city was under the command of Ma Wenlu originally from Xining. Many Hui people that had retreated from Shaanxi were there as well. After securing his supply lines, Zuo Zongtang laid siege to Suzhou in September 1873 with 15,000 troops. The fortress could not withstand Zuo's siege guns and the city fell on October 24. Zuo had 7,000 Hui people executed, and resettled the rest in southern Gansu, to ensure that the entire Gansu Corridor from Lanzhou to Dunhuang would remain Hui-free, preventing a possibility of future collusion between the Muslims of Gansu and Shaanxi and those of Xinjiang.Han and Hui loyal to Qing seized the land of Hui rebels in Shaanxi, so the Shannxi Hui were resettled in Zhanjiachuan in Gansu.[26]

Confusion

[edit]The rebels were disorganized and without a common purpose. Some Han Chinese rebelled against the Qing state during the rebellion, and rebel bands fought each other. The main Hui rebel leader, Ma Hualong, was even granted a military rank and title during the rebellion by the Qing dynasty. It was only later when Zuo Zongtang launched his campaign to pacify the region, did he decide which rebels who surrendered where going to be executed, or spared.[27]

Zuo Zongtang generally massacred New Teaching Jahriyya rebels, even if they surrendered, but spared Old Teaching Khafiya and Sunni Gedimu Rebels if they surrendered. Ma Hualong belonged to the New Teaching, and Zuo executed him, while Hui generals belonging to Old teaching like Ma Qianling, Ma Zhan'ao and Ma Anliang were granted amnesty and even promoted in the Qing military. Moreover, an army of Han Chinese rebels led by Dong Fuxiang surrendered and joined Zuo Zongtang.[27] General Zuo accepted the surrender of Hui people belonging to Old Teaching, provided they surrender large amounts of military equipm`ent and supplies, and were relocated. He refused to accept surrenders of New Teaching Muslims who still believed in its teachings, since the Qing classified them as a dangerous heterodox cult, like the White Lotus Buddhists. Zuo said, "The only distinction is between the innocent and rebellious, there is none between Han and Hui".[28]

The Qing authorities decreed that the Hui rebels who were violently attacking were merely heretics, not representative of the entire Hui population, like the heretical White Lotus did not represent all Buddhists.[29] The Qing authorities decreed that there were two different Muslim sects, the "old" religion and "new" religion, and that the new were heretics and deviated like White Lotus deviated from Buddhism and Daoism, and stated its intention to inform the Hui community that it was aware that the original Islamic religion was one united sect, before the new "heretics", saying they would separate Muslim rebels by which sect they belonged to.[30]

Nature of the Rebellion

[edit]During the rebellion, some Hui people never even joined the rebels. A Hui leader, Wang Dagui, fought on the side of the Qing dynasty against Hui rebels, and was awarded for doing so, until he and his family were all killed by the rebels.[31] In addition, the Hui Chinese rebel leaders never declared a Jihad, and never stated that they wanted to establish an Islamic state, in contrast to the Xinjiang Turki Muslims who called for Jihad. Instead of overthrowing the government, the rebels wanted to exact revenge from local corrupt officials and others who did them injustices.[32]

When Ma Hualong originally negotiated with the Qing authorities in 1866, he agreed to a "surrender", giving up thousands of foreign weapons, spears, swords, and 26 cannons. Ma assumed a new name signifying loyalty to the Dynasty, Ma Chaoqing. Mutushan, the Manchu official, hoped that this would lead to other Muslims following his lead and surrendering, however, Ma Hualong's surrender had no effect, the rebellion continued to spread.[33][34] Even when Ma Hualong was sentenced to death, Zuo canceled the execution when Ma Hualong surrendered for the second time in 1871, surrendering all his weapons, such as cannons, gingalls, shotguns, and western weapons. Zuo also ordered him to convince other leaders to surrender. Zuo then discovered a hidden cache of 1,200 western weapons in Ma Hualong's headquarters in Chin-chi-pao, and Ma failed to persuade the others to surrender, then Ma, male members of his family, and many of his officers were killed.[35] Zuo then ordered that he would accept the surrenders of New Teaching Muslims who admitted that they were deceived, radicalized, and misled by its doctrines. Zuo excluded khalifas and mullas from the surrender.[36]

As noted in the previous sections, Zuo relocated Han Chinese from Hezhou as a reward for the Hui leader Ma Zhanao when he and his followers surrendered and joined the Qing in crushing the rebels. Zuo also moved Shaanxi Muslim refugees from Hezhou, only allowing the native Gansu Muslims to stay. Ma Zhanao and his Hui forces were then recruited into the Green Standard Army of the Qing military.[37]

Situation of Hui Muslims in Non rebellious areas

[edit]Hui Muslims living in areas not in rebellion were completely unaffected by the revolt, with no restrictions being placed on them, nor did they try to join the rebels. Professor Hugh D. R. Baker stated in his book "Hong Kong images: people and animals", that the Hui Muslim population of Beijing was unaffected by the Muslim rebels during the Dungan revolt.[38] Elisabeth Allès wrote that the relationship between Hui Muslim and Han peoples continued normally in the Henan area, with no ramifications or consequences from the Muslim rebellions of other areas. Allès wrote in the document "Notes on some joking relationships between Hui and Han villages in Henan" published by French Center for Research on Contemporary China that "The major Muslim revolts in the middle of the nineteenth century which involved the Hui in Shaanxi, Gansu and Yunnan, as well as the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, do not seem to have had any direct effect on this region of the central plain."[39]

Rebellion in Xinjiang

[edit]

Pre-rebellion situation in Xinjiang

[edit]By the 1860s, Xinjiang had been under Qing rule for a century: it had been conquered in 1754, being formerly controlled by Zunghar Khanate.[40] Zunghar Khanate's core population, the Oirats, became subject to a genocide. But the new territories, being mostly of semi-arid or desert character, were not attractive to Han settlers except some traders, so the area became resettled by other people like Uyghurs etc. The entire Xinjiang was administratively divided into three parts ("circuits"; Chinese: 路, lu):

- The North-of-Tianshan Circuit (天山北路, Tianshan Beilu), including the Ili basin and Dzungaria. (This region roughly corresponds to the modern Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, including prefectures it controls and a few smaller adjacent prefectures).

- The South-of-Tianshan Circuit (天山南路, Tianshan Nanlu). Ir included the "Eight cities", i.e. the "Four Western Cities" (Khotan, Yarkand, Yangihissar, Kashgar) and the "Four Eastern Cities" (Ush, Aqsu, Kucha, Karashahr).

- The Eastern Circuit (东路, Donglu), in eastern Xinjiang, centered around Urumqi.

The General of Ili, stationed in Huiyuan Cheng (Ili), had the overall military command in all three circuits. He was also in charge of the civilian administration (directly in the North-of-Tianshan Circuit, and via local Muslim (Uyghur) begs in the South Circuit). However, the Eastern Circuit was subordinated in the matters of civilian administration to the Gansu province.

Trying (not always successfully) to prevent repetition of incursions of Afaqi khojas from Kokand into Kashgaria, such as those of Jahangir Khoja in the 1820s or Wali Khan in 1857, Qing government had increased the troops level in Xinjiang to some 50,000. There were both Manchu and Han units in the province; the latter, having been recruited mostly in Shaanxi and Gansu, had a heavily Hui (Dungan) component. A large part of the Qing army in Xinjiang was based in the Nine Forts of the Ili Region, but there were also forts with Qing garrisons in most other cities of Xinjiang as well.

The cost of maintaining this army was much higher than the taxation of the local economy could sustainably provide, and required subsidies from the central government - which, however, became unfeasible by the 1850-60s due to the costs of fighting against Taiping and other rebellions in the Chinese heartland. The Qing authorities in Xinjiang responded by raising taxes and introducing new ones, and selling official posts to the highest bidders (e.g. that of governor of Yarkand to Rustam Beg of Khotan for 2,000 yambus, and that of Kucha to Sa'id Beg for 1,500 yambus). The new officeholders would then proceed to recoup their investment by fleecing their subject population.

Increasing tax burden and corruption only added to the discontent of the Xinjiang people, who had long suffered both from the maladministration of Qing officials and the local begs subordinated to them and from the destructive invasions of the khojas. The Qing soldiers in Xinjiang, however, still were not paid on time or properly equipped.

With the start of the rebellion in Gansu and Shaanxi in 1862, rumors started spreading among the Hui (Dungans) of Xinjiang that the Qing authorities are preparing a wholesale preemptive slaughter of the Hui people in Xinjiang, or in a particular community. The opinions on the veracity of these rumors differ: while Tongzhi Emperor described them as "absurd" in his edict of September 25, 1864, Muslim historian generally believe that massacres were indeed planned, if not by the imperial government, then by various local authorities. Thus it was the Dungans that usually were to revolt in most Xinjiang towns, although the local Turkic people - Taranchis, Kyrgyz, or Kazakhs - would usually quickly join the fray.

Multi-centric rebellion

[edit]The first spark of the rebellion in Xinjiang was small enough for the Qing authorities to extinguish easily. On March 17, 1863, some 200 Dungans from the village of Sandaohe (a few miles west of Suiding), supposedly provoked by a rumor of a preemptive Dungan massacre, attacked Tarchi (塔勒奇城, Taleqi Cheng), one of the Nine Forts of the Ili. The rebels seized the weapons from the fort's armory and killed soldiers of its garrison, but were soon defeated by government troops from other forts and killed themselves.

It was not until the next year that the rebellion broke out again – this time, almost simultaneously in all three Circuits of Xinjiang, and on a scale that made suppressing it beyond the ability of the authorities.

On the night of June 3–4, 1864, the Dungans of Kucha, one of the cities South of Tianshan, rose, soon joined by the local Turkic people. The Han fort, which, unlike many other Xinjiang locations, was located inside of the town, rather than outside of it, fell within a few days. Government buildings were burnt and some 1000 Hans and 150 Mongols were killed. Neither of the Dungan or Turkic leaders of the rebellion having enough authority in the entire community to become commonly recognized as a leader, the rebels instead choose a person who had not participated in the rebellion, but was known for his spiritual role: Rashidin (Rashīdīn) Khoja, a dervish and the custodian of the grave of his ancestor of saintly fame, Arshad-al-Din (? - 1364 or 65). Over the next three years, he was to send military expeditions east and west, attempting to bring the entire Tarim Basin under his control; however, his expansion plans were to be frustrated by Yaqub Beg.

Just three weeks after Kucha, the rebellion started in the Eastern Circuit. The Dungan soldiers of the Ürümqi garrison rebelled on June 26, 1864, soon after learning about the Kucha rebellion. The two Dungan leaders were Tuo Ming (a.k.a. Tuo Delin), a New Teaching ahong from Gansu, and Suo Huanzhang, an officer with close ties to Hui religious leaders as well. Large parts of the city were destroyed, the tea warehouses burned, and the Manchu fortress besieged. Then the Ürümqi rebels started advancing westward through what is today Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture, taking the cities of Manas (also known then as Suilai) on July 17 (the Manchu fort there fell on September 16) and Wusu (Qur Qarausu) on September 29.

On October 3, 1864, the Manchu fortress of Ürümqi also fell to the joint forces of Ürümqi and Kuchean rebels. In a pattern that was to repeat in other Han forts throughout the region, the Manchu commander, Pingžui, preferred to explode his gunpowder, killing himself and his family, rather than surrender.

The Dungan soldiers in Yarkand in Kashgaria learned of the Qing authorities' plan to disarm or kill them, and rose in the wee hours of July 26, 1864. Their first attack on the Manchu fort (which was outside of the walled Muslim city) failed, but it still cost 2,000 Qing soldiers and their families their lives. In the morning, the Dungan soldiers entered the Muslim city, where some 7,000 Hans were massacred. The Dungans being numerically few compared to the local Turkic Muslims, they picked a somewhat neutral party – one Ghulam Husayn, a religious man from a Kabul noble family - as the puppet padishah.

By the early fall of 1864, the Dungans of the Ili Basin in the "Northern Circuit" rose too, encouraged by the success of Ürümqi rebels at Wusu and Manas, and worried by the prospects of preemptive repressions by the local Manchu authorities. The Ili General (the Ili Jiangjun, 伊犁将军) Cangcing, hated by the local population as a corrupt oppressor, was sacked by the Qing government after his troops had been defeated by the rebels at Wusu, and Mingsioi was appointed to replace them. His attempts to negotiate with the Dungans were in vain though; on November 10, 1864, the Dungans rose both in Ningyuan (the "Taranchi Kuldja"), the commercial center of the region, and Huiyuan (the "Manchu Kuldja"), the military and administrative center of the region. Kulja's Taranchis (Turkic-speaking farmers who were to form later part of the Uyghur people) joined in the rebellion. When the local Muslim Kazakhs and Kyrgyz felt that the rebels gained the upper hand, they joined it as well; on the other hand, the Buddhist Kalmyks, and Xibe mostly stayed loyal to the Qing government.

Ningyuan fell to the Dungan and Turki rebels at once, but the strong government force at Huiyuan made the insurgents retreat after 12 days of heavy fighting in the streets of the city. The local Hans, seeing the Manchus winning, joined forces with them. However, the Qing forces' counter-offensive failed. The imperial troops lost their artillery and the "Ili General" Mingsioi barely escaped capture. With the fall of Wusu and Aksu, the Qing garrison, entrenched in the Huiyuan fortress, was completely cut off from the rest of empire-controlled territory; Mingxu had to send his communications to Beijing via Russia.

While the Qing forces in Huiyuan successfully repelled the next attack of the rebels (12 December 1864), the rebellion kept spreading through the northern part of the province (Dzungaria), where the Kazakhs were glad to take revenge on the Kalmyk people that used to rule the area in the past.

For the Chinese New Year of 1865, the Hui leaders of Tacheng (Chuguchak) invited the local Qing authorities and Kalmyk nobles to assemble in the Hui mosque, in order to swear a mutual oath of peace. But once the Manchus and Kalmyks were in the mosque, the Hui rebels seized the city armory, and started killing the Manchus. After two days of fighting, the Muslims were in control of the town, while the Manchus were besieged in the fortress. However, with the Kalmyk's help, the Manchus were able to retake the Tacheng area by the fall of 1865. This time, it was the Hui rebels turn to be locked up in the mosque. The fighting resulted in the destruction of Tacheng and the surviving residents fleeing the town[citation needed].

Both the Qing government in Beijing and the beleaguered Kulja officials asked the Russians for assistance against the rebellion (via Russian envoy in Beijing, Alexander Vlangali (Влангали), and via the Russian commander in Semirechye, General Gerasim Kolpakovsky (Колпаковский) respectively). The Russians, however, were diplomatically non-committal: on the one hand, as Vlangali wrote to Saint Petersburg, a "complete refusal" would be bad for Russia's relations with Beijing; on the other hand, as Russian generals in Central Asia felt, seriously helping China against Xinjiang's Muslims would do nothing to improve Russia's problems with its own new Muslim subjects – and in case the rebellion were to succeed and form a permanent Hui state, having been on the Qing's side would do nothing good for Russia's relations with that new neighbor. The decision was thus made in Saint Petersburg in 1865 to avoid offering any serious help to the Qing, beyond agreeing to train Chinese soldiers in Siberia - should they send any - and to sell some grain to the defenders of Kuldja on credit. The main priority of Russian government was in guarding its border with China and preventing any possibility of the spread of the rebellion into Russia's own domain.

Considering that offense is the best defense, Kolpakovsky suggested to his superiors in February 1865 that Russia should go beyond defending its border and move in force into Xinjiang's border area, seizing Chuguchak, Kuldja and Kashgar areas and colonizing the area with Russian settlers - all to better protect the Romanovs' empire's other domains. The time was not ripe for such an adventure, however: as Foreign Minister Gorchakov noted, such a breach of neutrality would be not a good thing if China does recover its rebel provinces, after all.

Meanwhile the Qing forces in the Ili Valley did not fare well. In April 1865, the Huining (惠宁) fortress (today's Bayandai (巴彦岱), located between Yining and Huiyuan), fell to the rebels after three months' siege. Its 8,000 Manchu, Xibe, and Solon defenders were massacred, and two survivors, their ears and noses cut off, sent to Huiyuan - Qing's last stronghold in the Valley - to tell the Governor General about the fate of Huining.

Most of the Huiyuan (Manchu Kulja) fell to the rebels on January 8, 1866. Most of the residents and garrison perished; some 700 rebels died as well. Mingsioi, still holding out in the Huiyuan fortress with the remainder of his troops, but having run out of food, sent a delegation to the rebels, bearing a gift of 40 sycees of silver[41] and four boxes of green tea, and offering to surrender, provided the rebels guarantee their lives and allow them to keep their allegiance to the Qing government. Twelve Manchu officials with their families left the citadel along with the delegation. The Huis and Taranchis received the delegation and allowed the refugees from Huiyuan to settle in Yining ("the Old Kuldja"). However, the rebels would not accept Mingsioi's condition, and required instead that he surrender immediately and recognize the authority of the rebels. As Mingsioi rejected the rebels' proposal, the rebels proceeded to storm the citadel at once. On March 3, the rebels having broken into the citadel, Mingsioi assembled his family and staff in his mansion, and blew it up, dying under its ruins. This was the temporary end, for the time being, of the Qing rule in the Ili Valley.

Yaqub Beg in Kashgaria

[edit]

As reported by Muslim sources, the Qing authorities in Kashgar did not just intend to eliminate local Dungans, but in fact managed to carry out such a preemptive massacre in the summer of 1864. Perhaps this weakening of the local Dungan contingent resulted in the rebellion been initially not as successful in this area as in the rest of the province. Although the Dungan rebels were able to seize Yangihissar, neither they nor the Kyrgyz of Siddiq Beg could break into either into the Manchu forts outside of Yangihissar and Kashgar, nor into the walled Muslim city of Kashgar itself, held by Qutluq Beg, a local Muslim appointee of the Qing.

Unable to take control of the region on their own, the Dungan and Kyrgyz turned for help to Kokand's ruler Alim Quli. The help arrived in the early 1865, in the form both spiritual and material. The spiritual part consisted of Buzurg Khoja (also known as Buzurg Khan), member of the influential Afaqis family of khojas, whose religious authority could be expected to raise the rebellious spirit of the populace. He was a fine heir of the long family tradition of starting mischief in Kashgaria, being a son of Jahangir Khoja and brother of Wali Khan Khoja. The material part - as well as the expected conduit of Kokandian influence in Kashgaria - consisted of Yaqub Beg, a young but already well known Kokandian military commander, with an entourage of a few dozen Kokandian soldiers, who became known in Kashgaria as Andijanis.

Although Siddiq Beg's Kyrgyz had already taken the Muslim town of Kashgar by the time Buzurg Khoja and Yaqub Beg arrived, he had to allow the popular khoja to settle in the former governor's residence (the urda). Siddiq's attempts to assert his dominance were crushed by Yaqub Beg's and Buzurg's forces. The Kyrgyz then had to accept Yaqub's authority.

With his small, but comparatively well disciplined and trained army, made of the local Dungans and Kashgarian Turkic people (Uighurs, in modern terms), their Kyrgyz allies, Yaqub's own Kokandians, as well as some 200 soldiers sent by the ruler of Badakhshan, Yaqub Beg was able not only to take the Manchu fortress and the Han Chinese town of Kashgar during 1865 (the Manchu commander in Kashgar, as usual, blowing himself up), but to defeat much larger force sent by the Rashidin of Kucha, who was trying to dominate the Tarim Basin region himself.

While Yaqub Beg was asserting his authority over Kashgaria, the situation back home in Kokand changed radically. In May 1865, Alim Quli lost his life while defending Tashkent against the Russians; many of his soldiers (primarily, of Kyrgyz and Kipchak background) deemed it advisable to flee for comparative safety of Kashgaria. They appeared at the borders of Yaqub Beg's domain in early September 1865. Afghan warriors assisted Yaqub Beg.[42] Yaqub Beg's rule was unpopular among the natives. One of the native Kashgaris, a warrior and a chieftan's son, said "During the Chinese rule there was everything; there is nothing now." There was also a falling-off in trade.[43]

Yaqub Beg's Kashgaria Declares Jihad against Dungans

[edit]The Taranchi Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang initially cooperated with the Dungans(Hui people) when they rose in revolt but abandoned them afterwards because the Hui people attempted to subject the entire region to their rule. The Taranchi massacred the Dungans at Kuldja and driving the rest through Talk pass to the Ili valley.[44] The Hui people in Xinjiang where neither trusted by the Qing authorities and the Turkestani Muslims.[45]

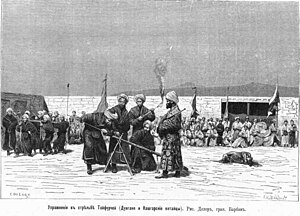

Yaqub Beg's Kokandi Andijani Uzbek forces declared a Jihad against Dungan rebels under T'o Ming. Fighting broke out between Dungan and Kokandi Uzbek rebels in Xinjiang. Yaqub Beg enlisted Han militia under Xu Xuegong in order to fight against the Dungan troops under T'o Ming. T'o Ming's Dungan forces were defeated by Yaqub Beg's troops in the Battle of Urumqi (1870), who planned to conquer Dzungaria. Yaqub intended to seize all Dungan territory.[46] Poems were written about the victories of Yaqub Beg's forces over the Hans and the Dungans .[47] Yakub Beg seized Aksu from Dungan forces and forced them north of the Tian Shan, committing massacres upon the Dungan people (tunganis).[48] Independent Han Chinese militia (who were not affiliated with the Qing government) joined both the Turkic forces under Yaqub Beg, and the Dungan rebels. In 1870, Yaqub Beg had 1,500 Han Chinese troops with his Turkic forces attacking Dungans in Urumqi. The following year, in 1871, the Han Chinese militia then joined the Dungans in fighting against the Turkic forces.[49]

Foreign relations of Kashgaria Yaqub Beg

[edit]Russia and Britain signed several treaties with Yaqub Beg's regime in Kashgar, Yaqub sought to secure British and Russian aid for his government.

Relations with Russia

[edit]Relations between Yaqub Beg and the Russian Empire alternated between hostile fighting and peaceful diplomatic exchanges.

The Russians were extremely hateful to the native population of Kashgar (because of close contacts their elite with Kokand khans who recently where expelled during Russian conquest of Turkestan), which would have ruined Yaqub Beg if he sought extensive aid from them, which he was inclined to originally.[50]

Ottoman and British support for Yaqub Beg

[edit]The Ottoman Empire and the British Empire both recognized Yaqub Beg's state and supplied him with thousands of guns.[51]

Qing reconquest of Xinjiang

[edit]As Qing General Zuo Zongtang moved into Xinjiang to crush the Muslim rebels under Yaqub Beg, he was joined by Dungan (Hui people) General Ma Anliang and his forces, which were composed entirely out of Dungan people believing in Islam. General Dong Fuxiang had an army of both Hans and Dungan people. Ma Anliang and his Dungan troops began the attack on the Muslim rebel forces, reconquering Xinjiang for Empire of the Great Qing.[52] General Dong Fuxiang's army seized the Kashgaria and Khotan area.[53] Dong Fuxiang's army took Khotan.[54]

General Zuo put a conciliatory policy toward the Muslim rebels in place, pardoning Muslims who did not rebel, and he also pardoned rebels who surrendered if they joined only because of religion. If rebels assisted the government against the rebel Muslims they received rewards.[55] In contrast to General Zuo, the Manchu leader Dolongga wanted to massacre all the Muslims and saw them all as the enemy.[52] Zuo also instructed General Zhang Yao that 'The Andijanis are tyrannical to their people; government troops should comfort them with benevolence. The Andijanis are greedy in extorting from the people; the government troops should rectify this by being generous.', telling him to not mistreat the Turkic Muslim natives of Xinjiang.[56] Zuo wrote that the main targets were only the 'die-hard partisans' and their leaders, Yaqub Beg and Bai Yanhu.[57] The natives were not blamed or mistreated by the Qing troops, a Russian wrote that the soldiers under General Liu 'acted very judiciously with regard to the prisoners whom he took . . . . His treatment of these men was calculated to have a good influence in favour of the Empire of the Great Qing' .[58]

Zuo Zongtang, who was previously a general of Xiang Army, was the commander in chief of all Qing troops participating in this counterinsurgency. His subordinates were the Han Chinese General Liu Jintang and Manchu Jin Shun.[59]

Liu Jintang's forces had modern German artillery while Jin Shun's forces did not, Chin-shun's advance was not as rapid as Liu's. After Liu bombarded Ku-mu-ti, Muslim rebel casualties numbered 6,000 dead. Bai Yanhu was forced to flee for his life. The Qing forces entered Urumqi unopposed. Zuo Zongtang wrote that Yaqub Beg's soldiers had modern western weapons but were cowardly: 'The Andijani chieftain Yaqub Beg has fairly good firearms. He has foreign rifles and foreign guns, including cannon using explosive shells [Kai Hua Pao]; but his are not as good nor as effective as those in the possession of our government forces. His men are not good marksmen, and when repulsed they simply ran away.'[60]

Dabancheng was destroyed by Liu's forces in April. Yaqub's subordinates defected to the Qing forces or fled, as his forces started to fall apart.[61] The oasis fell easily to the Qing troops. Toksun fell to Liu's army on April 26.[62]

Zuo Zongtang employed divide and conquer tactics on the Xinjiang, sending messages to the people in Kashgaria that they had been fooled by the Central Asian troops under Yaqub Beg who persuaded them to rebel. Yaqub Beg became nervous because the tactic worked, and he executed several natives in Kashgaria. His forces fell apart after fighting.[63]

Liu's cavalry inflicted 600 deaths on Bai Yanhu's Muslim rebel forces before reaching Gucheng (nowadays Qitai County).[64]

All the official and private residences had been destroyed alike, and the Muslim population had been compelled by Bai Yenhu to follow him in his retreat. He appears to have been the commander of that portion of the rebel army which was left round Korla. Not only was Kashgaria deserted by its inhabitants, but so was the whole area controlled by Yakub Beg's forces round about. Some, indeed, had fled to the mountains, but these were afraid to return when they saw the Qing army established in their homes. And then the Qing amry followed out their usual plan by settling fresh Han Chinese, Manchu and Mongol people in the town. The Mongol noble, Cha-hi-telkh, was directed to move up some hundreds of the members of his tribe to occupy this important post, to restore the homes and to refill the fields; and while this work of restoration was proceeding on territory conquered by Qing troops, that through which they passed in hostile guise was subjected to far other treatment. On the 9th of October Qing army marched against Korla from two sides, and on that day a cavalry skirmish took place, in which fifteen of Bai Yanhu's horsemen were slain, and two taken prisoners. Some volunteers in Bai's army told Qing troops that Bai Yanhu had withdrawn with all his forces to Kucha. When Qing army had exhausted their stock of information they beheaded them. The same day they entered Korla, which they found to be completely deserted, although not flooded. The walls remained, but many of the houses had been thrown down. Here the general was nearly reduced to a desperate plight because the provision, which was transported by cart and camel, did not come up. And a prospect of starvation compelling the victorious army to retreat. But fortunately a good solution struck the competent general. They found that some stores might conceal in the city which the rebels had been unable to carry away with them. Accordingly the whole army set to work to search the houses, and to dig into the ground in all likely places for hidden stores. Their toil was soon rewarded, and "several tens of thousand catties' weight of food" were discovered. However, these were only a slight supply for an army of men which was probably under 10,000 strong.

The massive retreat of the rebel army made their control range smaller and smaller. The next advance of Qing army, which they could not expect to be as unopposed as their late one, would bring them into the plain of Kashgaria. No sooner had Karashar and Korla fallen into their possession than an edict was issued inviting the Mohammedan descendants to return to their home and many of them accepted the invitation. In this quarter the arms of Empire of the Great Qing were not disgraced by any excesses, and moderation towards the unarmed population extenuated their severity towards armed forces. [65]

Yaqub Beg lost more than 20,000 men by desertion and at the hands of the enemy. He consequently conceived that it would be prudent to withdraw still farther into his territory, and accordingly left Karashar after a few days' residence in Korla. Some weeks before the occurrence of these striking events Yaqub Beg had sent an envoy to Tashkent to solicit the aid of the Russians against the advancing Qing army. But the Russians only gave his messenger fair words, and did not interfere with Mr. Kamensky's commercial transactions with the Qing army. At the moment, too, Russia was so busily occupied in Europe that she had no leisure to devote to the Xinjiang issue.[66]

General Zhang Yao captured the small towns of Chightam and Pidjamin the middle of April without encountering any serious opposition. And from the latter of these places, some fifty miles east of Turfan, commenced that concerted movement with his superior, Zuo Zongtang, which was to overcome all Kashgarian resistance. A glance at the map will show that Yakub Beg at Turfan was caught fairly between two fires by armies advancing from Urumqi and Pidjam, and if defeated his line of retreat was greatly exposed to an enterprising enemy. Upon Qing army becoming aware of the success of their preliminary movements and a general advance was ordered in all directions. It is evident that Qing army were met at first with a strenuous resistance at Devanchi and the forcing of the Tian Shan defiles had not been accomplished when news reached the garrison that their ruler had been expelled from Turfan by a fresh Qing army. It was then that confusion spread fast through all ranks of the followers of Yakub Beg; in that hour of doubt and unreasoning panic the majority of his soldiers either went over to the enemy or fled in headlong flight to Kashgaria. In this moment of desperation the Athalik Ghazi still bore himself like a good soldier. Outside Turfan he gave battle to Qing army, and though driven from the field by overwhelming odds he yet once more made a stand at Toksun, forty miles west of Turfan. And when a second time defeated withdrew to Kashgaria to make fresh efforts to withstand Qing army. Yakub Beg probably lost in these engagements.[67]

While halting some days at Korla, Jin Shun heard that Bai Yanhu was coercing the people east of Kucha at Tsedayar and other places, and compelling them to withdraw to Kucha and to destroy their crops. He at once resolved to frustrate the plan, and set out in person at the head of 1,500 light infantry and 1,000 cavalry to protect the inhabitants. By forced marches, sometimes carried on through the better part of the night, he reached Tsedayar on the 17th of October, when he learnt that Bai Yanhu had driven off the whole of the population, and was already at Luntai, on the road to Kucha. At the next village to Tsedayar, a fortified post known as Tangy Shahr, he found that Bai Yanhu was still ahead of him, and that he was setting fire to the villages on his line of march. Jin Shun left a portion of his infantry behind to put out the conflagration, and resolutely pressed on with the remainder of his force to Luntai. This small town had also been set on fire, but here the rapidity of Qing general's advance was rewarded with the news that the enemy's army, with a large number of the inhabitants, was only a short distance ahead. The rear-guard, composed of 1,000 cavalry, was soon touched, and the Kashgaria, emboldened by the small numbers of Qing troops, came on to the attack in gallant fashion. Their charge was broken, however, by the steadiness of Qing infantry, armed with excellent rifles, and the cavalry performed the rest. The Kashgaria left 100 slain on the field of battle and twelve prisoners. From these latter it was discovered that the main body of 2,000 soldiers was some distance on the road to Kucha, with the family of Bai Yanhu and the villagers under its charge. It was too late to advance further that day, but on the next the forward movement was resumed. A large multitude—" some tens of thousands of people"—was speedily sighted by the advanced guard, but on examining these through glasses it was discovered that scarcely more than a thousand carried arms. All the troops were then brought to the front, and Jin Shun issued instructions that all those found with arms in their hands should be slain, but the others spared.[68]

The armed portion of the rebel army drew off from the unarmed, leaving in the midst the large assemblage of rebel villagers who were being carried off to Kucha. These were sent to the rear by order of Jin Shun, and distributed in such of the villages as were most convenient. In the meanwhile a sharp fight took place a few miles in the rear of the old position, near a village called Arpa Tai. The action appears to have been well contested, but the superior tactics and weapons of Jin Shun's small army prevailed; and the rebel army retreated with considerable loss and in great disorder. Kin Shun followed up his success with marvelous rapidity and restless energy, while the rebel troops fled incontinently to Kucha, abandoning the people and the control range to Qing troops. The unfortunate inhabitants implored with piteous entreaties the mercy of the conqueror, and it is with genuine satisfaction we record the fact that Jin Shun informed them of their safety, and bade them have no further alarm.[69]

By this time it is probable that Qing army had been largely reinforced from the rear, they began the attack against Kucha. When Qing troops appeared before its walls they found that a battle was proceeding there between the Kashgarian soldiers and the townspeople, who refused to accompany them in a further retreat westward. On the appearance of Qing army, the Kashgarian force evacuated the city and joined battle with it on the western side of Kucha. Qing soldiers attacked them immediately with little success on the first place; and a charge of the cavalry, numbering some four or five thousand men, was only repulsed with some difficulty. But the cannon of Qing soldiers were playing with remarkable effect upon the rebel forces and Qing reserves were every moment coming upon the ground. The infantry were at last ordered to advance, under the cover of a heavy artillery fire, and the cavalry made a charge at a most opportune moment. The whole army then broke and fled in irretrievable confusion, leaving more than a thousand of their number on the ground. The numbers on each side were probably about 10,000 men, and it was won as much by superior tactics and skill as by brute force and courage. All the movements of Qing army were characterized by remarkable forethought, and evinced the greatest ability on the part of the general and his lieutenants, as well as obedience, valor, and patience on the part of his soldiers. The rapid advance from Kuhwei to Karashar, the forced march thence to Luntai, the capture of Kucha and the forbearance of Qing troops towards the inhabitants, all combine to make this portion of the war most creditable to Empire of the Great Qing and her generals. The reason given in the Official Report for the Kashgarian authorities attempting to carry off the population was that the rebels wished in the first place to deprive Qing armed forces of all assistance, thus making further pursuit very difficultly. And in the second place, to ingratiate themselves with Qing authorities reesablished in Kashgaria by delivering this large mass of Turkic Muslims into his hands. Bai Yanhu was therefore certainly not Hakim Khan. It is clear that he must have been either a Dungan refugee or a subordinate of Beg Bacha's.[70]

A depot was formed at Kucha, and a large body of troops remained there as a garrison; but the principal administrative measures were directed to the task of improving the position of the Turkic Muslim population. A board of administration was instituted for the purpose of providing means of subsistence for the destitute, and for the distribution of seed-corn for the benefit of the whole community. It had also to supervise the construction of roads, and the establishment of ferry boats, and of post-house in order to facilitate the movements of trade and travel and expedite the transmission of mails. Magistrates and prefects were appointed[71] to all the cities, and special precautions were taken against the outbreak of epidemic or of famine. All these wise provisions were carried out promptly. And in the most matter-of-fact manner, just as if the legislation and administration of alien states were the daily avocations of the Empire of the Great Qing. There is no reason to believe that in the vast region from Turfan to Kucha Qing authorities have departed from the statesmanlike and beneficent schemes which marked their re-installation as rulers; and whatever harshness or cruelty they manifested towards the Dungan revolts and the rebel soldiers was more than atoned for by the mildness of their treatment of the people.

On the 19th, or more probably the 22nd of October, Jin Shun resumed his forward movement, encountering no serious opposition. His first halt was at a village called Hoser, where he halted for one night. He employed in inditing the report to Peking, which described the successes and movements of the previous three weeks. At the next town, known as Bai, Jin Shun halted to await the arrival of the rear-guard under General Zhang Yao. This force came up before the close of October, and the advance against Aksu was resumed. Up to this point the chief interest centered in the army south of the Tian Shan and the achievements of Jin Shun. Our principal, in fact our only, authority for this portion of the campaign is the Peking Gazette.

We have now to describe the movements of the Northern Army, which was under the immediate command of Zuo Zongtang. This army was operating in the north of the state, in complete secrecy. That general had an army of 28,000 men at the most moderate computation. By some it was placed at a higher figure; but a St. Petersburg paper, on the authority of a Russian merchant, who had been to Manas, computed it to be of that strength. It was concentrated in the neighborhood of Manas, and along the northern skirts of the Tian Shan; and also on the [72] frontier of the Russian dominions in Kuldja. To all appearance this army was consigned to a part of enforced inactivity since it was impossible to enter Kuldja, and thus proceed by their old routes through the Bedel Pass or Muzat River. But it was not so; the travels of Colonel Prjevalsky in the commencement of 1877 had not been unobserved by Qing authorities, and it was assumed that where a Russian officer with his Cossack following could go, there also could go a Qing troop. By those little-known mountain passes, which are made by the Tekes and Great Yuldus rivers, Qing army which was under General Zuo crossed over into Kashgaria; and it is probable that the two armies joined in the neighborhood of Bai. It was by this stroke of strategy on the part of Zuo Zongtang that Qing army found themselves before the walls of Aksu. At that moment, the imperial army was an overwhelming army at the very sight of which all thought of resistance died away from the hearts of the rebel peoples and garrisons. General Zuo appeared before the walls of Aksu, the bulwark of Kashgaria on the east. And its commandant, who were panic and stricken, abandoned his post at the first onset. He was subsequently taken prisoner by an officer of Kuli Beg, and executed. Qing army then advanced on Uqturpan, which also surrendered without a blow. It is said that the Chinese have not published any detailed description of this portion of the war, and we are consequently unable to say what their version is of those reported atrocities at Aksu and Uqturpan, of which the Russian papers have made so much. There is no doubt that a very large number of refugees fled to Russian territory, perhaps 10,000 in all, and these brought with them the tales of fear and exaggerated alarm. We may feel little hesitation in accepting the assertion as true, that the armed garrisons were slaughtered without exception; but that the unarmed population and the women and children shared the same fate we distinctly refuse to credit. There is every precedent in favor of the assumption that a more moderate policy was pursued, and there is no valid reason[73] why Qing authorities should have dealt with Aksu and Uqturpan differently to Kucha or Turfan. The case of Manas has been greatly insisted upon by the agitators on this "atrocity" question; but there is the highest authority for asserting that only armed men were massacred there. This was what Qing troops had always done; it was a national custom, and they certainly did not depart from it in the case of the Dungan and Kashgaria. But there is no solid ground for convicting them of any more heinous crime, even in the instances of Manas and Aksu, which are put so prominently forward.

Early in December all Qing troops began their last attack against the capital city of the Kashgarian regime, and on December 17th Qing army took a fatal assault. The rebel troops were finally defeated and the residual troops started to withdraw to Yarkant, whence he fled to Russian territory. With the fall of Kashgaria Qing's reconquest of Xinjiang was completed, and the other cities, Yangi Hissar and Yarkant, speedily shared the same fate. Khotan and Sarikol also sent in formal promises of subjection. But the capture of Kashgaria virtually closed the rebel. No further rebellion was encountered, and the reestablished Qing authorities began the task of recover and reorganization. The Qing forces beheaded Turkic rebel commanders, and also tortured Ottoman Turkish military officers who served with the rebels.[54] When the city of Kashgaria fell, the greater portion of the army, knowing that they could expect no mercy at the hands of Qing authorities, fled to Russian territory, and then spread reports of fresh Chinese massacres, which probably only existed in their own imagination.[74]

It was stated at the time that the strength of the Empire of the Great Qing has been thoroughly demonstrated and the vindication of her prestige is complete. Whatever danger there may be to the permanence of Qing's triumph lies rather from Russia than from the peoples of Tian Shan Nan Lu; nor is there much danger that the Chinese laurels will become faded even before a European foe. Zuo Zongtang and his generals such as Jin Shun and Chang Yao, accomplished a task which would reflect credit on any army and any country. They have given a luster to the modern Chinese administration which must stand it in good stead, and they have acquired a personal renown that will not easily depart. Qing Empire's reconquest of Xinjiang is beyond doubt the most remarkable event that has occurred in Asia during the last fifty years, and it is quite the most brilliant achievement of a Chinese army, led by Chinese generals, that has taken place since Emperor Qianlong subdued the country more than a century ago. It also proves, in a manner that is more than unpalatable to us, that the Chinese possess an adaptive faculty that must be held to be a very important fact in every-day politics in Central Asia. They reconquered Kashgaria with European weapons and by careful study of Western science and technology. Their soldiers marched in obedience to instructors trained on the Prussian principle; and their generals maneuvered their troops in accordance with the teachings of Moltke and Manteuffel. Even in such minor matters as the use of telescopes and field glasses we could find this Chinese army well supplied. Nothing was more absurd than the picture drawn by some over-wise observer of this army, as consisting of soldiers fantastically garbed in the guise of dragons and other hideous appearances. All that belonged to an old-world theory. The rebel troops were as widely different from all previous Chinese armies in Central Asia as it well could be; and in all essentials closely resembled that of a European power. Its remarkable triumphs were chiefly attributable to the thoroughness with which China had in this instance adapted herself to Western notions"[75][76]

Aftermath

[edit]Punishment

[edit]Yaqub Beg and his son Ishana Beg's corpses were "burned to cinders" on display. This angered the population in Kashgar, but Qing troops quashed a rebellious plot by Hakim Khan.[77] Surviving members of Yaqub Beg's family included his 4 sons, 4 grandchildren (2 grandsons and 2 granddaughters), and 4 wives. They either died in prison in Lanzhou, Gansu or were killed by Qing government. His sons Yima Kuli, K'ati Kuli, Maiti Kuli, and grandson Aisan Ahung were the only survivors in 1879. They were all underage children at that time. They were put on trial and sentenced to an agonizing death if they were complicit in their father's rebellious "sedition". If they were innocent of their father's crimes, they were to be sentenced to castration and serving as a eunuch slave to Qing troops. Afterwards when they reached 11 years old, and handed over to the Imperial Household to be executed or castrated.[78][79][80] In 1879, it was confirmed that the sentence of castration was carried out, Yaqub Beg's son and grandsons were castrated by the Chinese court in 1879 and turned into eunuchs to work in the Imperial Palace.[81]

Memorials

[edit]On January 25, 1891, a temple was constructed by Liu Jintang. He had been one of the generals participating the counterinsurgency against Dungan revolt and at that time he was the Governor of Gansu. The temple was built in the capital of Gansu as a memorial to the victims who died during the Dungan revolt in Kashgaria and Dzungaria. The victims numbered 24,838 and included officials, peasants, and members of all social classes and ethnic groups. It was named Chun Yi Ci. Another temple was already built in honor to the Xiang Army soldiers who fought during the revolt.[82]

Flight of the Dungans to the Russian Empire

[edit]The failure of the revolt led to some immigration of Hui people into Imperial Russia. According to Rimsky-Korsakoff (1992), three separate groups of the Hui people fled to Russian Empire across the Tian Shan Mountains during the exceptionally severe winter of 1877/78:

- The first group, of some 1000 people, originally from Turpan in Xinjiang, led by Ma Daren (马大人), also known as Ma Da-lao-ye (马大老爷), reached Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan.

- The second group, of 1130 people, originally from Didaozhou (狄道州) in Gansu, led by ahong A Yelaoren (阿爷老人), were settled in the spring of 1878 in the village of Yardyk some 15 km from Karakol in Eastern Kyrgyzstan.

- The third group, originally from Shaanxi, led by Bai Yanhu (白彦虎; also spelt Bo Yanhu; 1829(?)-1882), one of the leaders of the rebellion, were settled in the village of Karakunuz (now Masanchi), is modern Zhambyl Province of Kazakhstan. Masanchi is located on the northern (Kazakh) side of the Chu River, 8 km north from the city Tokmak in north-western Kyrgyzstan. This group numbered 3314 on arrival.

Another wave of immigration followed in the early 1880s. In accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Saint Petersburg signed in February 1881, which required the withdrawal of the Russian troops from the Upper Ili Basin (the Kulja area), the Hui and Taranchi (Uighur) people of the region were allowed to opt for moving to the Russian side of the border. Most people choose that option; according to the Russian statistics, 4,682 Hui moved to Russian Empire under the treaty. They migrated in many small groups between 1881–83, settling in the village of Sokuluk some 30 km west of Bishkek, as well as in a number of points between the Chinese border and Sokuluk, in south-eastern Kazakhstan and northern Kyrgyzstan.

The descendants of these rebels and refugees still live in Kyrgyzstan and neighboring parts of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. They still call themselves the Hui people (Huizu), but to the outsiders they are known as Dungan, which means Eastern Gansu in Chinese.

Since the Sino-Soviet split occurred, Soviet propaganda writers such as Rais Abdulkhakovich Tuzmukhamedov call the Dungan revolt (1862–1877) a "national liberation movement" for their political proposes.[83]

Increase in Hui Military Power

[edit]The Rebellion increased the power of Hui Generals and military men in the Empire of the Great Qing. Many Hui Generals who served in the Rebellion, like Ma Anliang, and Dong Fuxiang were promoted by the Emperor of Qing Empire. This led Hui armies to fight again in the Dungan Revolt (1895) against rebels, and in the Boxer Rebellion against Christian Western Armies. The Hui Gansu Braves rose to fame for protecting the Emperor and Polytheist Han Chinese against the Chinese Christians and Westerners.

Ma Fuxiang, Ma Qi, and Ma Bufang were the descendants of the Hui military men from this era, and they became important and high ranking Generals in the Republic of China National Revolutionary Army.

Border Dispute with Russia

[edit]The Russians occupied the city of Kuldja in Xinjiang during the revolt. After General Zuo Zongtang and his Xiang Army crushed the rebels, they demanded Russia return the occupied regions.

General Zuo Zongtang was outspoken in calling for war against Russia, hoping to settle the matter by attacking Russian forces in Xinjiang with his Xiang army. In 1878, tension increased in Xinjiang. Zuo massed Qing troops toward the Russian occupied Kuldja. Chinese forces also fired on Russian expeditionary forces originating from Yart Vernaic, expelling them, resulting in a Russian retreat.[84]

After the incompetent negotiator Chong Hou, who was bribed by the Russians. He signed a treaty granting Russia extraterritorial rights, consulates, control over trade, and an indemnity without permission from Qing government. Thereafter the massive uproar by the Chinese literati ensued. Some of them were calling for the death of Chong Hou. Zhang Zhidong demanded the beheading of Chong Hou to stand up for the government to Russia and declare the treaty invalid. He also stated that "The Russians must be considered extremely covetous and truculent in making the demands and Chong Hou was extremely stupid and absurd in accepting them . . . . If we insist on changing the treaty, there may not be trouble; if we do not, we are unworthy to be called a state.'[85] The Chinese literati demanded the government mobilize the arm forces against Russia. The government acted after this, important posts were given to officers from the Xiang Army and Charles Gordon advised the Chinese.[86]

The Russians were in a very bad diplomatic and military position against China. Besides, Russia feared the threat of military conflict, forcing them into diplomatic negotiations instead.[87]

See also

[edit]- Dungan Revolt (1895)

- Islam during the Qing Dynasty

- List of rebellions in China

- Taiping Rebellion

- Nien Rebellion

- Miao Rebellion (1854–73)

- Panthay Rebellion

- Punti–Hakka Clan Wars

- Nepalese-Tibetan War

- List of wars and disasters by death toll

Footnotes

[edit] This article incorporates text from Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afd. Letterkunde, Volume 4, Issues 1-2, by Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Afd. Letterkunde, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afd. Letterkunde, Volume 4, Issues 1-2, by Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Afd. Letterkunde, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Sectarianism and religious persecution in China: a page in the history of religions, Volume 2, by Jan Jakob Maria Groot, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Sectarianism and religious persecution in China: a page in the history of religions, Volume 2, by Jan Jakob Maria Groot, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Accounts and papers of the House of Commons, by Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, a publication from 1871, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Accounts and papers of the House of Commons, by Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, a publication from 1871, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events, Volume 4, a publication from 1880, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events, Volume 4, a publication from 1880, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Translations of the Peking Gazette, by 1880, a publication from [year missing], now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Translations of the Peking Gazette, by 1880, a publication from [year missing], now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The American annual cyclopedia and register of important events of the year ..., Volume 4, a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The American annual cyclopedia and register of important events of the year ..., Volume 4, a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Appletons' annual cyclopedia and register of important events: Embracing political, military, and ecclesiastical affairs; public documents; biography, statistics, commerce, finance, literature, science, agriculture, and mechanical industry, Volume 19, a publication from 1886, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Appletons' annual cyclopedia and register of important events: Embracing political, military, and ecclesiastical affairs; public documents; biography, statistics, commerce, finance, literature, science, agriculture, and mechanical industry, Volume 19, a publication from 1886, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Chinese times, Volume 5, a publication from 1891, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese times, Volume 5, a publication from 1891, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Canadian spectator, Volume 1, a publication from 1878, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Canadian spectator, Volume 1, a publication from 1878, now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 893. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John Powell (2001). John Powell (ed.). Magill's Guide to Military History, Volume 3 (illustrated ed.). Salem Press. p. 1072. ISBN 0-89356-014-6. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ Lipman (1998), p. 120–121

- ^ Sir H. A. R. Gibb. Encyclopedia of Islam, Volumes 1-5. Brill Archive. p. 849. ISBN 90-04-07164-4. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence (1991). The search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 191. ISBN 0-393-30780-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Vol. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

The Ch'ing began to win only with the arrival of To-lung-a (1817-64) as Imperial Commissioner. Originally a Manchu banner officer, To-lung-a had, through the patronage of Hu Lin-i, risen to be a commander of the Hunan Army (the force under him being identified as the Ch'u-yung).40 In 1861, To-lung-a helped Tseng Kuo-ch'üan to recover Anking from the Taipings and, on his own, caputred Lu-chou in 1862. His yung-ying force proved to be equally effective against the Muslims. In March 1863, his battalions captured two market towns that formed the principal Tungan base in eastern Shensi. He broke the blockade around Sian in August and pursued the Muslims to western Shensi. By the time of his death in March 1864, in a battle against Szechwanese Taipings who invaded Shensi, he had broken the back of the Muslim Rebellion in that province. A great many Shensi Muslims had, however, escaped to Kansu, adding to the numerous Muslim forces which had already risen there.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Vol. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

While the rebellion in Shensi was clearly provoked by Han gentry and officials, in Kansu it seems that the Muslims had taken the initiative, with the New Teaching group under Ma Hua-lung playing a large role. As early as October 1862, some Muslim leaders, spreading the word of an impending Ch'ing massacre of Muslims, organized themselves for a siege of Ling-chou, a large city only forty-odd miles north of Ma Hua-ling's base, Chin-chi-pao. Meanwhile, in south-eastern Kansu, Ku-yuan, a strategic city thwart a principal transport route, was attacked by the Muslims. Governor-general En-lin, in Lanchow, saw no alternative to a policy of reconciliation. In January 1863, at his recommendation Peking issued an edict especially for Kansu, reiterating the principle of non-discrimination towards the Muslims. But as in Shensi, both Han and Muslim local corps.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ John King Fairbank, Kwang-Ching Liu, Denis Crispin Twitchett, ed. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Vol. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

Tso had also been assured of a soluation to his financial and logistical problems. In war-torn Shensi and Kansu, food was scarce and prices extremely high. Tso laid down the rule that his forces would go into major battle only when there were three month's supplies on hand.57 Not only munitions but also large amounts of grain had to be brought to Shensi and Kansu from other provinces. To finance his supplies, Tso plainly had to depend on Peking's agreement to the formula adopted by many dynasties of the past: 'support the armies in the northwest with the resources of the southeast'. In 1867, five provinces of the south-east coast were asked by the throne to contribute to a 'Western expedition fund' (Hsi-cheng hsiang-hsiang) totallying 3,24 million taels annually. The arrangement came under Ch'ing fiscal practice of 'interprovincial revenue assistance' (hsieh-hsiang), but at a time when these provinces were already assessed for numerous contributions to meet the needs of Peking or of other provinces.58 Tso reported, as early as 1867, to a strategem that would compel the provinces to produce their quotas for his campaigns. He requested and obtained the throne's approval for his arranging lump-sum laons form foreign firms, guaranteed by the superintendents of customs at the treaty ports and confirmed by the seals of the provincial governors involved, to be repaid by these provinces to the foreign firms by a fixed date.