User:Travis Jaico R/Sample page

| Mickey Mouse | |

|---|---|

| Mickey Mouse & Friends character | |

Mickey Mouse as he appears in a 1928 poster | |

| First appearance | Steamboat Willie (1928) |

| Created by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks |

| Designed by | Walt Disney Ub Iwerks (original design) Fred Moore (1930s redesign) |

| Voiced by | Walt Disney (1928–1947, 1955–1962) Carl W. Stalling (1929) Jimmy MacDonald (1947–1978) Wayne Allwine (1977–2009)[1] Bret Iwan (2009–present) Chris Diamantopoulos (2013–present) (see voice actors) |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | |

| Species | Mouse |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Mickey Mouse family Pluto (dog) |

| Significant other | Minnie Mouse |

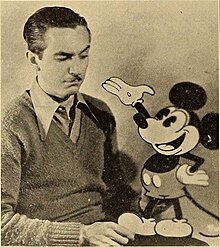

Mickey Mouse is an American cartoon character co-created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. The longtime icon and mascot of the Walt Disney Company, Mickey is an anthropomorphic mouse who typically wears red shorts, large shoes, and white gloves. He is often depicted alongside his girlfriend Minnie Mouse, his pet dog Pluto, his friends Donald Duck and Goofy and his nemesis Pete among others (see Mickey Mouse universe)

| Trolls Band Together | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Walt Dohrn |

| Screenplay by | Elizabeth Tippet[2] |

| Based on | Good Luck Trolls by Thomas Dam |

| Produced by | Gina Shay |

| Starring | |

| Edited by | Nick Fletcher |

| Music by | Theodore Shapiro |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $95 million[4] |

| Box office | $209.6 million[5][6] |

Trolls Band Together is a 2023 American animated jukebox musical comedy film produced by DreamWorks Animation and distributed by Universal Pictures, based on the Good Luck Trolls dolls from Thomas Dam. It serves as the sequel to Trolls World Tour (2020), and the third installment in the Trolls franchise. The film was directed by Walt Dohrn and co-directed by Tim Heitz (in his feature directorial debut), from a screenplay written by Elizabeth Tippet. Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger, who wrote the screenplays for the previous installments, returned to serve as executive producers alongside Dannie Festa. Justin Timberlake, Anna Kendrick, Zooey Deschanel, Christopher Mintz-Plasse, Icona Pop, Anderson .Paak, Ron Funches, Kenan Thompson, Kunal Nayyar and Dohrn reprise their voice roles from previous films, with newcomers Eric André, Kid Cudi, Daveed Diggs, Troye Sivan, Camila Cabello, Amy Schumer, Andrew Rannells, RuPaul and Zosia Mamet joining the ensemble voice cast. In the film, Branch (Timberlake) and Poppy (Kendrick), who are officially a couple, attempt to rescue Floyd (Sivan) while reuniting Branch's brothers after the boyband phenomenon, BroZone, was disbanded.

Ideas for a third Trolls film began prior to the release of Trolls World Tour in April 2020, when Timberlake expressed interest in participating during his Apple Music takeover. DreamWorks Animation officially confirmed the third film's development in November 2021. New characters for the film were announced in March 2023, along with new cast members and the title. Despite being predominantly CGI animation, with some additional animation by DNEG, the film includes some 2D animation sequences with animation styles inspired by Yellow Submarine (1968) and Fantasia (1940). Theodore Shapiro, who previously composed the score for Trolls World Tour, returned to compose the score for this film.

Trolls Band Together was theatrically released in Denmark on October 12, 2023, and in the United States on November 17. The film has grossed $209 million worldwide and received positive reviews from critics and audiences.

Plot

[edit]Years ago, Branch and his four older brothers John Dory, Spruce, Clay and Floyd perform as a boyband called BroZone. Their hesitations and stress of maintaining their boyband images prevent them from performing the "Perfect Family Harmony", a powerful ability that a family of Trolls can achieve when they are in complete sync. After a failed concert, John Dory, Spruce and Clay argue, break up the band and go their separate ways, breaking Floyd and Branch's hearts. Floyd, Branch's closest brother, also leaves, but not before saying goodbye to Branch and promising to come back one day. Branch is left alone to be raised by his grandmother Rosiepuff.

In the present, Branch and Poppy attend Bridget and Gristle's wedding in Bergen Town. They are interrupted by John Dory, who says that Floyd has been captured by Velvet and Veneer, two Mount Rageon teenagers who wish to be pop stars. The siblings have imprisoned Floyd in a diamond perfume bottle, which they use to extract his essence and improve their singing, but the process could eventually kill him. As the Perfect Family Harmony is the only thing that can shatter diamond, Branch reluctantly agrees to help John Dory find their brothers and rescue Floyd. Along with Poppy and Tiny Diamond, they set out in John Dory's armadillo-like portable van named Rhonda while Bridget and Gristle go on their honeymoon.

They find Spruce at the Vacay Island resort, where he has changed his name to Bruce and started a family. Spruce is reluctant to help, until his wife and 13 kids, after a successful practice concert, convince him to do so. The group later finds Clay, who quickly decided to help, at an abandoned Bergen miniature golf course, inhabited by a hidden colony of Pop Trolls who do not know that the Bergens are no longer their enemies, having been separated from the other Pop Trolls when they fled the final Trollstice.[a] Viva, the colony's leader, reveals herself to be Poppy's long-lost sister. At first, Poppy is delighted, but the visit turns sour when Viva refuses to believe the Bergens have changed, and tries to stop Poppy's group from leaving the golf course. They manage to escape thanks to Clay, and Poppy and Viva separate with broken hearts.

Meanwhile, Velvet and Veneer continue to strip Floyd of his essence, and Velvet reveals that she forged a letter in order to bait Floyd's brothers to come and rescue him. Furthermore, the siblings' assistant Crimp invents shoulder-pad suits that enhance the extraction, which they plan to use when they capture all of BroZone.

The Trolls make it to Mount Rageous, but once again argue and fail to reach Perfect Family Harmony. When his brothers decide they will split up again after saving Floyd, Branch scolds them for abandoning their family and treating him like a baby, revealing to them that he lived his whole life alone after their grandmother got eaten by a Bergen. Branch, Poppy and Tiny leave to rescue Floyd on their own, leaving John Dory, Spruce and Clay feeling guilty for their past actions, having second thoughts in splitting up again and in shock about their grandmother's fate. The trio finally find Floyd, but Velvet and Veneer capture John Dory, Spruce and Clay, making a rescue even more difficult. Meanwhile, Bridget and Gristle stumble onto the golf course, where they are attacked by the Putt-Putt trolls until Viva notices them and convinces them to help her sister.

Branch and Poppy confront Velvet and Veneer when they start mingling with a crowd of fans, prompting them to drive away in their limo. During the ensuing chase, Velvet and Veneer begin using the shoulder-pads to extract the essence from Branch's brothers in order to put on a show. Branch and Poppy are soon helped by Viva, Bridget and Gristle, and they save Branch's brothers, except Floyd.

Seeing that Floyd is just about out of essence, Branch tells his three brothers that they do not need to be perfect in order to be in harmony and they just have to be as they are as a family. Taking Branch's words to heart and accepting he has grown up, John Dory, Spruce and Clay decide to follow his lead. They, along with Poppy and Viva, perform the Perfect Family Harmony and break free of their prisons just as Floyd loses the last of his essence and dies, but he is quickly revived by his brothers' essences and love. Veneer, who had been second-guessing Velvet's machinations, publicly confesses their crimes, simultaneously enraging his sister and sending themselves to prison. Shortly after this happens, Poppy kisses Branch.

The Trolls return to Vacay Island and witness BroZone's comeback concert, joined by Kismet, another band Branch was once part of. Later, Poppy and Viva join BroZone, under Branch's proposal, as honorary members.

Voice cast

[edit]Main

[edit]- Justin Timberlake as Branch, a survivalist Pop Troll and Poppy's boyfriend

- Iris Dohrn as Baby Branch. Dohrn had previously voiced young Poppy in the first film.

- Anna Kendrick as Poppy, queen of the Pop Trolls and Branch's girlfriend

- Kenan Thompson as Tiny Diamond, a baby glittery Hip-Hop Troll and Guy Diamond's son

- Walt Dohrn as:

- King Peppy, the former king of the Pop Trolls and Poppy and Viva's father

- Cloud Guy, an anthropomorphic cloud

- Interdimensional Hustle Traveler

- Ron Funches as Cooper, one of the princes of the Funk Trolls

- Anderson .Paak as Darnell, one of the princes of the Funk Trolls and Cooper's younger twin brother

- Kunal Nayyar as Guy Diamond, a glittery Pop Troll and Tiny Diamond's single father

- David Fynn as Biggie, a large, friendly British Pop Troll and the owner of Mr. Dinkles. He replaced James Corden from the first 2 films.

- Kevin Michael Richardson as Mr. Dinkles, Biggie's pet worm

- Eric André as John Dory, the oldest of Branch's brothers and the former leader of BroZone

- Daveed Diggs as Spruce, the second oldest of Branch's brothers and a former member of BroZone

- Kid Cudi as Clay, the third oldest of Branch's brothers and a former member of BroZone.

- Troye Sivan as Floyd, the fourth oldest of Branch's brothers and a former member of BroZone

- Camila Cabello as Viva, Poppy's long-lost older sister and the leader of the Putt-Putt Trolls

- Zosia Mamet as Crimp, an assistant to Velvet and Veneer

- Amy Schumer as Velvet, a Mount Rageon and Veneer’s older twin sister

- Brianna Mazzola as Velvet’s singing voice

- Andrew Rannells as Veneer, a Mount Rageon and Velvet's younger twin brother

- Christopher Mintz-Plasse as Gristle, the king of the Bergens and Bridget's fiancé-turned-husband

- Zooey Deschanel as Bridget, a former scullery maid, the queen of the Bergens and Gristle's fiancé-turned-wife

- Aino Jawo as Satin and Caroline Hjelt as Chenille, twin Pop Trolls that are conjoined by their hair who loves fashion

- RuPaul Charles as Miss Maxine, the wedding officiant for the wedding between King Gristle Jr. and Bridget

- Dillon Francis as Kid Ritz, a DJ from Mount Rageous

- GloZell Green as Grandma Rosiepuff, the grandmother of Branch and his brothers

- Patti Harrison as Brandy, Spruce's wife on Vacay Island

- Lance Bass as Boom, a member of the band Kismet

- JC Chasez as Hype, a member of the band Kismet

- Joey Fatone as Ablaze, a member of the band Kismet

- Chris Kirkpatrick as Trickee, a member of the band Kismet

Additional

[edit]- Nina Bakshi as BroZone fangirl

- Melissa Mabie as Aunt Smeed

- James Ryan as a Mount Rageous stage manager

- Tim Heitz as Lone Pooper

- Ryan Naylor as radio announcer

- Nick Fletcher as a concert announcer

- Secunda Wood as:

- BroZone stagehand

- Mount Rageon fangirl

- Roger Craig Smith as:

- A rock climbing instructor

- Lenny

- Mount Rageon fan

- Fred Tatasciore as a Vacaytioner with nachos

- Nick Kishiyama as:

- Cove

- Freddy

- Jakari Fraser as Windy

- Kayla Melikian as LaBreezey

- Titus Blake as Rainy

- Nicole Lynn Evans as a Putt-Putt Troll

Production

[edit]On April 9, 2020, Justin Timberlake expressed interest in participating in the future Trolls films during his Apple Music takeover, "I hope we make, like, seven Trolls movies, because it literally is the gift that keeps on giving".[7] On November 22, 2021, it was announced that a third Trolls film would be released in theaters on November 17, 2023.[8] Anna Kendrick and Justin Timberlake were confirmed to reprise their voice roles as Poppy and Branch, respectively. On March 28, 2023, with the release of the first official trailer, new cast members of the film were officially announced, including Eric André, Kid Cudi, Daveed Diggs, Troye Sivan, Camila Cabello, Amy Schumer, Andrew Rannells, RuPaul, and Zosia Mamet. Walt Dohrn returned to direct the third film after doing so in its predecessor, while Gina Shay returned to serve as producer. Tim Heitz was later announced as co-director. The same day of these announcements, DreamWorks Animation revealed the official title, Trolls Band Together.[9]

According to Shay, the idea for the film came about right after Trolls (2016). Although Trolls Band Together was predominantly CGI animation, the film includes some 2D animation sequences done by Titmouse, Inc.,[10] with animation styles inspired by Yellow Submarine (1968) and Fantasia (1940).[11] Additional animation was done by DNEG.

Music

[edit]On March 6, 2023, Theodore Shapiro was confirmed to compose the score for Trolls Band Together, returning from its predecessor.[12] On September 14, 2023, following the release of the second trailer, DreamWorks announced that NSYNC would perform an original song for the film, called "Better Place" marking the group's first song in 22 years.[13]

Release

[edit]Marketing

[edit]Universal and DreamWorks collaborated with several brands and product partnerships to promote the film for its marketing campaign, including ShineWater Beverages,[14] ICEE,[15] Shake Shack,[16] Southwest Airlines,[17] Candy,[18] CAMP Store,[19] and Puma,[20] as well as the international brands such as Zing Flowers.[21]

A video game based on the film, titled Trolls: Remix Rescue, was released on October 27, 2023 by DreamWorks Animation and Game Mill Entertainment for PlayStation 4 and 5, Xbox One and Series X, Nintendo Switch, and PC. In this game, which takes place after the events of the second film Trolls World Tour, Poppy, Branch, and the player character must embark on a quest to save the Troll Kingdom from Chaz the Smooth Jazz Troll when he tries to take over the place by hypnotizing the residents with his saxophone.[22]

Theatrical

[edit]Trolls Band Together began releasing in international markets, starting with Denmark on October 12, 2023,[5] and was later released in the United States on November 17. After Trolls World Tour (2020) was simultaneously released on video on demand in addition to a limited number of theaters due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this film returned to being released exclusively in theaters.[8]

Home media

[edit]Trolls Band Together was released on VOD on December 19, 2023.[23] The film was released on Blu-ray, DVD, and 4K UHD on January 16, 2024.[24]

It was added to Peacock on March 15, 2024.[25] As part of Universal's deal with Netflix, the film will stream on Peacock for the first four months starting on of the pay-TV window, before moving to Netflix for the next ten starting in July 2024, and returning to Peacock for the remaining four starting in January 2025.[26][27]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Trolls Band Together grossed $103 million in the United States and Canada, and $106.5 million in other territories, for a worldwide gross of $209.5 million.[5][6]

In the United States and Canada, Trolls Band Together was released alongside Next Goal Wins, The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes, and Thanksgiving, and was projected to gross $27–32 million from 3,800 theaters in its opening weekend.[28][4] The film made $9.4 million on its first day, including $1.3 million from Thursday night previews. It went on to debut $30.6 million, finishing second behind The Hunger Games.[29] The film made $17.8 million in its second weekend (a drop of 40.6%), finishing in fourth.[30]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 63% of 91 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 5.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Trolls Band Together serves up another amusing, eye-catching outing that should entertain young fans of the franchise while remaining perfectly painless for parents." Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 53 out of 100, based on 13 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews. Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale, same as the first film, while those polled by PostTrak gave it an 85% overall positive score, with 67% saying they would definitely recommend the film.[29]

Frank Scheck of The Hollywood Reporter gave the film a positive review, writing, "Elizabeth Tippet's screenplay garners laughs thanks to the sheer volume of jokes (the hit-to-miss ratio is pretty unbalanced), and there are several amusing one-liners about the music business."[31] Tatiana Hullender of Screen Rant rated the film 2.5 out of 5 score, writing "Trolls Band Together shows clear signs of franchise fatigue, but a few new songs and vivid animation choices keep it afloat a little longer."[32]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hollywood Music in Media Awards | November 15, 2023 | Original Song – Animated Film | "Better Place" – Shellback, Justin Timberlake, and Amy Allen | Won | [33] |

| Song – Onscreen Performance (Film) | NSYNC – "Better Place" | Nominated | |||

| Music Supervision – Film | Angela Leus | Won | |||

| Music Themed Film or Musical | Trolls Band Together | Won | |||

| Soundtrack Album | Trolls Band Together | Nominated | |||

| Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards | July 13, 2024 | Favorite Animated Movie | Trolls Band Together | Nominated | [34] |

| Favorite Female Voice from an Animated Movie | Anna Kendrick | Won | |||

| Favorite Male Voice from an Animated Movie | Justin Timberlake | Nominated | |||

| Favorite Villain | Amy Schumer | Nominated |

The Walt Disney Company has been criticized for making purportedly sexist and racist content in the past, putting LGBT+ elements in their films, and not having enough LGBT+ representation. There have been controversies over alleged plagiarism, poor pay and working conditions, and poor treatment of animals. Disney has also been criticised for filming in the autonomous region of Xinjiang, where human rights abuses are taking place.[35]

Racism

[edit]Several of Disney's films have been considered to be racist; one of the company's most-controversial films Song of the South was criticized for portraying racial stereotypes. For that reason, the film was never released to home video in the U.S. or Disney+.[36] Other characters that have been called racist are Sunflower, a black centaurette who serves a white centaurette in Fantasia; the Siamese cats in Lady and the Tramp, who are considered to be overexaggerated as Asians, stereotypes of Native Americans in Peter Pan; and crows in Dumbo, who are depicted as African Americans who use jive talk, with their leader being named Jim Crow, believed to be in reference to racial segregation laws in the U.S.[37][38] When watching a film on Disney+ considered to have wrongful racist stereotypes, Disney added a disclaimer before the film starts to help avoid controversies.[39]

Plagiarism

[edit]Disney has also been accused a number of times of plagiarizing already existing works in its films. Most notably, The Lion King has many similarities in its characters and events to an animated series called Kimba the White Lion by animator Osamu Tezuka.[40] Atlantis: The Lost Empire also has many similarities to the anime show Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water that were considered so prevalent the latter show's creator Gainax was planning to sue Disney but was stopped by its series' network NHK.[41] Kelly Wilson, creator of the short The Snowman (2014), filed two lawsuits, one which came after the first was rescinded, against Disney for copyright infringement in Disney's animated film Frozen. Disney later settled the lawsuit with Wilson, allowing the company to create a sequel to Frozen.[42] Screenwriter Gary L. Goldman sued Disney over its film Zootopia, claiming he had earlier pitched an identical, same-titled story to the company. A judge dismissed the lawsuit, stating there was not enough evidence to prove any plagiarism.[43]

LGBT+ representation

[edit]Disney has been criticized for both putting LGBT+ elements into its films and for having insufficient LGBT+ representation in its media. In the live-action film Beauty and the Beast, director Bill Condon announced LeFou would be depicted as a gay character, prompting Kuwait, Malaysia, and a theater in Alabama to ban the film, and Russia to give it a stricter rating.[44] In Russia and several Middle Eastern countries, the Pixar movie Onward was banned for having Disney's first openly lesbian character Officer Specter, while others said Disney needed more representation of LGBT+ persons in its media.[45][46] Because of a scene featuring two lesbians kissing, Pixar's Lightyear was banned in 13 predominantly Muslim countries, and barely broke even at the box office.[47][48] In a leaked video of a Disney meeting, participants talked about pushing LGBT+ themes in the company's media, angering some people, who say the company is "trying to sexualize children", while others applauded its actions.[49]

Sexism

[edit]Some Disney Princess films have been considered to be sexist toward women. Snow White is said to be too worried about her appearance while Cinderella is deemed to have no talents. Aurora is also said to be weak because she is always waiting to be rescued. In some of the princess films, men have more dialogue, and there are more speaking male characters than female. Disney's more-recent films are considered to be less sexist than its earlier films.[50]

Animal cruelty and working conditions

[edit]In 1990, Disney paid $95,000 to avoid legal action over 16 animal-cruelty charges for beating vultures to death, shooting at birds, and starving some birds at Discovery Island. The company took these actions because they were attacking other animals and taking their food.[51] When Animal Kingdom first opened, there were concerns about the animals because a few of them died. Animal rights groups protested but the United States Department of Agriculture found no violations of animal-welfare regulations.[52] Disney has been accused of having poor working conditions. A protest by 2,000 workers at Disneyland in 2022 accused the company of poor pay at an average of $13 an hour, with some saying they were evicted from their homes.[53] In 2010, at a factory in China where Disney products were being made, workers experienced working hours three times longer than those prescribed by law, and one of the workers committed suicide.[54]

Possible sequels

[edit]Justin Timberlake claimed in April 2020 that a total of seven Trolls films were intended.[7]

In an interview, it was confirmed in regards to the comment from Timberlake that this will not be the last movie as there is a never-ending source material for the franchise.[7][55] In a later interview, it was confirmed that a Trolls 4 is highly possible if wanted.[56] For the next movie, they wanted to reunite One Direction.[57][58]

Company units

[edit]The Walt Disney Company operates three primary business segments:

- Disney Entertainment oversees the company's full portfolio of entertainment media and content businesses globally, including Walt Disney Studios, Disney General Entertainment Content, Disney Streaming and Disney Platform Distribution. The division is led by Alan Bergman and Dana Walden.

- ESPN is responsible for the management and supervision of the company's portfolio of sports content, products, and experiences across all of Disney's platforms worldwide, including its international sports channels. The division is led by James Pitaro.

- Disney Experiences is responsible for theme parks and resorts, cruise and vacation experiences, and consumer products such as toys, apparel, books, and video games. The division is led by Josh D'Amaro.

Leadership

[edit]

Current

[edit]- Board of directors[59]

- Mark Parker (Chairman)

- Mary Barra

- Amy Chang

- Jeremy Darroch

- Carolyn Everson

- Michael Froman

- James P. Gorman

- Bob Iger

- Maria Elena Lagomasino

- Calvin McDonald

- Derica W. Rice

- Executives[59]

- Bob Iger, Chief Executive Officer

- Asad Ayaz, Chief Brand Officer

- Alan Bergman, Co-Chairman, Disney Entertainment

- Sonia Coleman, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer

- Tinisha Agramonte, Senior Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer

- David Bowdich, Senior Vice President and Chief Security Officer

- Josh D'Amaro, Chairman, Disney Experiences

- Horacio Gutierrez, Senior Executive Vice President, Chief Legal and Compliance Officer

- Jolene Negre, Associate General Counsel and Secretary

- Hugh Johnston, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

- Carlos A. Gómez, Executive Vice President, Corporate Finance and Treasurer

- Alexia S. Quadrani, Executive Vice President, Investor Relations

- Brent Woodford, Executive Vice President, Controllership, Finance and Tax

- James Pitaro, Chairman, ESPN

- Kristina Schake, Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Communications Officer

- Dana Walden, Co-Chairman, Disney Entertainment

Past leadership

[edit]- Executive chairmen

- Bob Iger (2020–2021)

- Chairmen

- Walt Disney (1945–1960)

- Roy O. Disney (1964–1971)

- Donn Tatum (1971–1980)

- Card Walker (1980–1983)

- Raymond Watson (1983–1984)

- Michael Eisner (1984–2004)

- George J. Mitchell (2004–2006)

- John E. Pepper Jr. (2007–2012)

- Bob Iger (2012–2021)

- Susan Arnold (2022–2023)

- Mark Parker (2023–present)

- Vice chairmen

- Roy E. Disney (1984–2003)

- Sanford Litvack (1999–2000)[b][60]

- Presidents

- Walt Disney (1923–1945)

- Roy O. Disney (1945–1968)

- Donn Tatum (1968–1971)

- Card Walker (1971–1980)

- Ron W. Miller (1980–1984)

- Frank Wells (1984–1994)

- Michael Ovitz (1995–1997)

- Michael Eisner (1997–2000)

- Bob Iger (2000–2012)

- Chief executive officers (CEO)

- Roy O. Disney (1929–1971)

- Donn Tatum (1971–1976)

- Card Walker (1976–1983)

- Ron W. Miller (1983–1984)

- Michael Eisner (1984–2005)

- Bob Iger (2005–2020; 2022–present)

- Bob Chapek (2020–2022)

- Chief operating officers (COO)

- Card Walker (1968–1976)

- Ron W. Miller (1980–1984)

- Frank Wells (1984–1994)

- Thomas O. Staggs (2015–2016)

Awards and nominations

[edit]As of 2022, the Walt Disney Company has won 135 Academy Awards, 32 of them were awarded to Walt. The company has won 16 Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film, 16 for Best Original Song, 15 for Best Animated Feature, 11 for Best Original Score, 5 for Best Documentary Feature, 5 for Best Visual Effects, and several others as well special awards.[61] Disney has also won 29 Golden Globe Awards, 51 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) awards, and 36 Grammy Awards as of 2022.[62][63][64][c]

Financial data

[edit]Revenues

[edit]| Year | Studio Entertainment[d] | Disney Consumer Products[e] | Disney Interactive Media[83][84] | Parks & Resorts[f] | Disney Media Networks[g] | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2,593.0 | 724 | 2,794.0 | 6,111 | [85] | ||

| 1992 | 3,115 | 1,081 | 3,306 | 7,502 | [85] | ||

| 1993 | 3,673.4 | 1,415.1 | 3,440.7 | 8,529 | [85] | ||

| 1994 | 4,793 | 1,798.2 | 3,463.6 | 359 | 10,414 | [86][87][88] | |

| 1995 | 6,001.5 | 2,150 | 3,959.8 | 414 | 12,525 | [86][87][88] | |

| 1996 | 10,095[e] | 4,502 | 4,142[h] | 18,739 | [87][89] | ||

| 1997 | 6,981 | 3,782 | 174 | 5,014 | 6,522 | 22,473 | [90] |

| 1998 | 6,849 | 3,193 | 260 | 5,532 | 7,142 | 22,976 | [90] |

| 1999 | 6,548 | 3,030 | 206 | 6,106 | 7,512 | 23,435 | [90] |

| 2000 | 5,994 | 2,602 | 368 | 6,803 | 9,615 | 25,402 | [91] |

| 2001 | 7,004 | 2,590 | 6,009 | 9,569 | 25,790 | [92] | |

| 2002 | 6,465 | 2,440 | 6,691 | 9,733 | 25,360 | [92] | |

| 2003 | 7,364 | 2,344 | 6,412 | 10,941 | 27,061 | [93] | |

| 2004 | 8,713 | 2,511 | 7,750 | 11,778 | 30,752 | [93] | |

| 2005 | 7,587 | 2,127 | 9,023 | 13,207 | 31,944 | [94] | |

| 2006 | 7,529 | 2,193 | 9,925 | 14,368 | 34,285 | [94] | |

| 2007 | 7,491 | 2,347 | 10,626 | 15,046 | 35,510 | [95] | |

| 2008 | 7,348 | 2,415 | 719 | 11,504 | 15,857 | 37,843 | [96] |

| 2009 | 6,136 | 2,425 | 712 | 10,667 | 16,209 | 36,149 | [97] |

| 2010 | 6,701[i] | 2,678[i] | 761 | 10,761 | 17,162 | 38,063 | [98] |

| 2011 | 6,351 | 3,049 | 982 | 11,797 | 18,714 | 40,893 | [99] |

| 2012 | 5,825 | 3,252 | 845 | 12,920 | 19,436 | 42,278 | [100] |

| 2013 | 5,979 | 3,555 | 1,064 | 14,087 | 20,356 | 45,041 | [101] |

| 2014 | 7,278 | 3,985 | 1,299 | 15,099 | 21,152 | 48,813 | [102] |

| 2015 | 7,366 | 4,499 | 1,174 | 16,162 | 23,264 | 52,465 | [103] |

| 2016 | 9,441 | 5,528 | 16,974 | 23,689 | 55,632 | [104] | |

| 2017 | 8,379 | 4,833 | 18,415 | 23,510 | 55,137 | [105] | |

| 2018 | 9,987 | 4,651 | 20,296 | 24,500 | 59,434 | [106] | |

| Year | Studio Entertainment | Direct-to-Consumer & International | Parks, Experiences and Products | Media Networks[g] | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 10,065 | 3,414 | 24,701 | 21,922 | 59,434 | [107] |

| 2019 | 11,127 | 9,349 | 26,225 | 24,827 | 69,570 | [108] |

| 2020 | 9,636 | 16,967 | 16,502 | 28,393 | 65,388 | [109] |

| Year | Media and Entertainment Distribution | Parks, Experiences and Products | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 50,866 | 16,552 | 67,418 | [110] |

| 2022 | 55,040 | 28,705 | 83,745 | [111] |

| Year | Entertainment | Sports | Experiences | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 40,635 | 17,111 | 32,549 | 88,898 | [112] |

Operating income

[edit]| Year | Studio Entertainment[d] | Disney Consumer Products[e] | Disney Interactive Media[83] | Parks and Resorts[f] | Disney Media Networks[g] | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 318 | 229 | 546 | 1,094 | [85] | ||

| 1992 | 508 | 283 | 644 | 1,435 | [85] | ||

| 1993 | 622 | 355 | 746 | 1,724 | [85] | ||

| 1994 | 779 | 425 | 684 | 77 | 1,965 | [86][87] | |

| 1995 | 998 | 510 | 860 | 76 | 2,445 | [86][87] | |

| 1996 | 1,596[e] | −300[j] | 990 | 747 | 3,033 | [87] | |

| 1997 | 1,079 | 893 | −56 | 1,136 | 1,699 | 4,312 | [90] |

| 1998 | 769 | 801 | −94 | 1,288 | 1,746 | 4,079 | [90] |

| 1999 | 116 | 607 | −93 | 1,446 | 1,611 | 3,231 | [90] |

| 2000 | 110 | 455 | −402 | 1,620 | 2,298 | 4,081 | [91] |

| 2001 | 260 | 401 | 1,586 | 1,758 | 4,214 | [92] | |

| 2002 | 273 | 394 | 1,169 | 986 | 2,826 | [92] | |

| 2003 | 620 | 384 | 957 | 1,213 | 3,174 | [93] | |

| 2004 | 662 | 534 | 1,123 | 2 169 | 4,488 | [93] | |

| 2005 | 207 | 543 | 1,178 | 3,209 | 5,137 | [94] | |

| 2006 | 729 | 618 | 1,534 | 3,610 | 6,491 | [94] | |

| 2007 | 1,201 | 631 | 1,710 | 4,285 | 7,827 | [95] | |

| 2008 | 1,086 | 778 | −258 | 1,897 | 4,942 | 8,445 | [96] |

| 2009 | 175 | 609 | −295 | 1,418 | 4,765 | 6,672 | [97] |

| 2010 | 693 | 677 | −234 | 1,318 | 5,132 | 7,586 | [98] |

| 2011 | 618 | 816 | −308 | 1,553 | 6,146 | 8,825 | [99] |

| 2012 | 722 | 937 | −216 | 1,902 | 6,619 | 9,964 | [100] |

| 2013 | 661 | 1,112 | −87 | 2,220 | 6,818 | 10,724 | [101] |

| 2014 | 1,549 | 1,356 | 116 | 2,663 | 7,321 | 13,005 | [102] |

| 2015 | 1,973 | 1,752 | 132 | 3,031 | 7,793 | 14,681 | [103] |

| 2016 | 2,703 | 1,965 | 3,298 | 7,755 | 15,721 | [104] | |

| 2017 | 2,355 | 1,744 | 3,774 | 6,902 | 14,775 | [105] | |

| 2018 | 2,980 | 1,632 | 4,469 | 6,625 | 15,706 | [106] | |

| Year | Studio Entertainment | Direct-to-Consumer & International | Parks, Experiences and Products | Disney Media Networks | Total | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 3,004 | −738 | 6,095 | 7,338 | 15,689 | [107] | |

| 2019 | 2,686 | −1,814 | 6,758 | 7,479 | 14,868 | [108] | |

| 2020 | 2,501 | −2,806 | −81 | 9,022 | 8,108 | [109] | |

| Year | Media and Entertainment Distribution | Parks, Experiences and Products | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 7,295 | 471 | 7,766 | [110] |

| 2022 | 4,216 | 7,905 | 12,121 | [111] |

| Year | Entertainment | Sports | Experiences | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 1,444 | 2,465 | 8,954 | 12,863 | [112] |

History

[edit]1923–1934: Founding, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, and Silly Symphonies

[edit]In 1921, American animators Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks founded Laugh-O-Gram Studio in Kansas City, Missouri.[113] Iwerks and Disney went on to create short films at the studio. The final one, in 1923, was entitled Alice's Wonderland and depicted child actress Virginia Davis interacting with animated characters. While Laugh-O-Gram's shorts were popular in Kansas City, the studio went bankrupt in 1923 and Disney moved to Los Angeles, to join his brother Roy O. Disney, who was recovering from tuberculosis.[114] Shortly after Walt's move, New York film distributor Margaret J. Winkler purchased Alice's Wonderland, which began to gain popularity. Disney signed a contract with Winkler for $1,500, to create six series of Alice Comedies, with an option for two more six-episode series.[115][116] Walt and Roy Disney founded Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio on October 16, 1923, to produce the films.[117] In January 1926, the Disneys moved into a new studio on Hyperion Street and the studio's name was changed to Walt Disney Studio.[118]

After producing Alice films over the next 4 years, Winkler handed the role of distributing the studio's shorts to her husband, Charles Mintz. In 1927, Mintz asked for a new series, and Disney created his first series of fully animated shorts, starring a character named Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.[119] The series was produced by Winkler Pictures and distributed by Universal Pictures. Walt Disney Studios completed 26 Oswald shorts.[120]

In 1928, Disney and Mintz entered into a contract dispute, with Disney asking for a larger fee, while Mintz sought to reduce the price. Disney discovered Universal Pictures owned the intellectual property rights to Oswald, and Mintz threatened to produce the shorts without him if he did not accept the reduction in payment.[120][121] Disney declined and Mintz signed 4 of Walt Disney Studio's primary animators to start his own studio; Iwerks was the only top animator to remain with the Disney brothers.[122] Disney and Iwerks replaced Oswald with a mouse character originally named Mortimer Mouse, before Disney's wife urged him to change the name to Mickey Mouse.[123][124] In May 1928, Mickey Mouse debuted in test screenings of the shorts Plane Crazy and The Gallopin' Gaucho. Later that year, the studio produced Steamboat Willie, its first sound film and third short in the Mickey Mouse series, which was made using synchronized sound, becoming the first post-produced sound cartoon.[125] The sound was created using Powers' Cinephone system, which used Lee de Forest's Phonofilm system.[126] Pat Powers' company distributed Steamboat Willie, which was an immediate hit.[123][127][128] In 1929, the company successfully re-released the two earlier films with synchronized sound.[129][130]

After the release of Steamboat Willie at the Colony Theater in New York, Mickey Mouse became an immensely popular character.[130][123] Disney Brothers Studio made several cartoons featuring Mickey and other characters.[131] In August 1929, the company began making the Silly Symphony series with Columbia Pictures as the distributor, because the Disney brothers felt they were not receiving their share of profits from Powers.[128] Powers ended his contract with Iwerks, who later started his own studio.[132] Carl W. Stalling played an important role in starting the series, and composed the music for early films but left the company after Iwerks' departure.[133][134] In September, theater manager Harry Woodin requested permission to start a Mickey Mouse Club at his theater the Fox Dome to boost attendance. Disney agreed, but David E. Dow started the first-such club at Elsinore Theatre before Woodin could start his. On December 21, the first meeting at Elsinore Theatre was attended by around 1,200 children.[135][136] On July 24, 1930, Joseph Conley, president of King Features Syndicate, wrote to the Disney studio and asked the company to produce a Mickey Mouse comic strip; production started in November and samples were sent to King Features.[137] On December 16, 1930, the Walt Disney Studios partnership was reorganized as a corporation with the name Walt Disney Productions, Limited, which had a merchandising division named Walt Disney Enterprises, and subsidiaries called Disney Film Recording Company, Limited and Liled Realty and Investment Company; the latter of which managed real estate holdings. Walt Disney and his wife held 60% (6,000 shares) of the company, and Roy Disney owned 40%.[138]

The comic strip Mickey Mouse debuted on January 13, 1930, in New York Daily Mirror and by 1931, the strip was published in 60 newspapers in the US, and in 20 other countries.[139] After realizing releasing merchandise based on the characters would generate more revenue, a man in New York offered Disney $300 for license to put Mickey Mouse on writing tablets he was manufacturing. Disney accepted and Mickey Mouse became the first licensed character.[140][141] In 1933, Disney asked Kay Kamen, the owner of an Kansas City advertising firm, to run Disney's merchandising; Kamen agreed and transformed Disney's merchandising. Within a year, Kamen had 40 licenses for Mickey Mouse and within two years, had made $35 million worth of sales. In 1934, Disney said he made more money from the merchandising of Mickey Mouse than from the character's films.[142][143]

The Waterbury Clock Company created a Mickey Mouse watch, which became so popular it saved the company from bankruptcy during the Great Depression. During a promotional event at Macy's, 11,000 Mickey Mouse watches sold in one day; and within two years, two-and-a-half million watches were sold.[144][139][143] As Mickey Mouse become a heroic character rather than a mischievous one, Disney needed another character that could produce gags.[145] Disney invited radio presenter Clarence Nash to the animation studio; Disney wanted to use Nash to play Donald Duck, a talking duck that would be the studio's new gag character. Donald Duck made his first appearance in 1934 in The Wise Little Hen. Though he did not become popular as quickly as Mickey had, Donald Duck had a featured role in Donald and Pluto (1936), and was given his own series.[146]

After a disagreement with Columbia Pictures about the Silly Symphony cartoons, Disney signed a distribution contract with United Artists from 1932 to 1937 to distribute them.[147] In 1932, Disney signed an exclusive contract with Technicolor to produce cartoons in color until the end of 1935, beginning with the Silly Symphony short Flowers and Trees (1932).[148] The film was the first full-color cartoon and won the Academy Award for Best Cartoon.[125] In 1933, The Three Little Pigs, another popular Silly Symphony short, was released and also won the Academy Award for Best Cartoon.[131][149] The song from the film "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", which was composed by Frank Churchill—who wrote other Silly Symphonies songs—became popular and remained so throughout the 1930s, and became one of the best-known Disney songs.[133] Other Silly Symphonies films won the Best Cartoon award from 1931 to 1939, except for 1938, when another Disney film, Ferdinand the Bull, won it.[131]

1934–1949: Golden Age of Animation, strike, and wartime era

[edit]

In 1934, Walt Disney announced a feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It would be the first cel animated feature and the first animated feature produced in the US. Its novelty made it a risky venture; Roy tried to persuade Walt not to produce it, arguing it would bankrupt the studio, and while widely anticipated by the public, it was referred to by some critics as "Disney's Folly".[150][151] Walt directed the animators to take a realistic approach, creating scenes as though they were live action.[152][153] While making the film, the company created the multiplane camera, consisting of pieces of glass upon which drawings were placed at different distances to create an illusion of depth in the backgrounds.[154] After United Artists attempted to attain future television rights to the Disney shorts, Walt signed a distribution contract with RKO Radio Pictures on March 2, 1936.[155] Walt Disney Productions exceeded its original budget of $150,000 for Snow White by ten times; its production eventually cost the company $1.5 million.[150]

Snow White took 3 years to make, premiering on December 12, 1937. It was an immediate critical and commercial success, becoming the highest-grossing film up to that point, grossing $8 million (equivalent to $169,555,556 in 2023 dollars); after re-releases, it grossed a total of $998,440,000 in the US adjusted for inflation.[156][157] Using the profits from Snow White, Disney financed the construction of a new 51-acre studio complex in Burbank, which the company fully moved into in 1940 and where the company is still headquartered.[158][159] In April 1940, Disney Productions had its initial public offering, with the common stock remaining with Disney and his family. Disney did not want to go public but the company needed the money.[160]

Shortly before Snow White's release, work began on the company's next features, Pinocchio and Bambi. Pinocchio was released in February 1940 while Bambi was postponed.[155] Despite Pinocchio's critical acclaim (it won the Academy Awards for Best Song and Best Score and was lauded for groundbreaking achievements in animation),[161] the film performed poorly at the box office, due to World War II affecting the international box office.[162][163]

The company's third feature Fantasia (1940) introduced groundbreaking advancements in cinema technology, chiefly Fantasound, an early surround sound system making it the first commercial film to be shown in stereo. However, Fantasia similarly performed poorly at the box office. [164][165][166] In 1941, the company experienced a major setback when 300 of its 800 animators, led by one of the top animators Art Babbitt, went on strike for 5 weeks for unionization and higher pay. Walt Disney publicly accused the strikers of being party to a communist conspiracy, and fired many of them, including some of the studio's best.[167][168] Roy unsuccessfully attempted to persuade the company's main distributors to invest in the studio, which could no longer afford to offset production costs with employee layoffs.[169] The anthology film The Reluctant Dragon (1941), ran $100,000 short of its production cost, contributing to the studio's financial woes.[clarification needed][170]

While negotiations to end the strike were underway, Walt and studio animators embarked on a 12-week goodwill visit to South America, funded by the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.[171] During the trip, the animators began plotting films, taking inspiration from the local environments and music.[172] As a result of the strike, federal mediators compelled the studio to recognize the Screen Cartoonist's Guild and several animators left, leaving it with 694 employees.[173][168] To recover from their financial losses, Disney rushed into production the studio's 4th animated feature Dumbo (1941) on a cheaper budget, which performed well at the box office, infusing the studio with much needed cash.[161][174] After US entry into World War II, many of the company's animators were drafted into the army.[175] 500 United States Army soldiers occupied the studio for 8 months to protect a nearby Lockheed aircraft plant. While they were there, the soldiers fixed equipment in large soundstages and converted storage sheds into ammunition depots.[176] The United States Navy asked Disney to produce propaganda films to gain support for the war, and with the studio badly in need of profits, Disney agreed, signing a contract for 20 war-related shorts for $90,000.[177] Most of the company's employees worked on the project, which spawned films such as Victory Through Air Power, and others which included some of the company's characters.[178][175]

In August 1942, Bambi was finally released as Disney's 5th feature after 5 years in development, performing poorly at the box office.[179] Later, as products of the South American trip, the studio released the features Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballeros (1944);[175][180] which showcased the studio's new strategy of releasing package films, collections of short cartoons grouped to make feature films. Both performed poorly. Disney released more package films through the rest of the decade, including Make Mine Music (1946), Fun and Fancy Free (1947), Melody Time (1948), and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949), to try to recover from its financial losses.[175] The studio began producing less-expensive live-action films mixed with animation, beginning with Song of the South (1946) which would become one of Disney's most controversial films.[181][182] As a result financial issues, Disney began re-releasing its feature films in 1944.[182][183] In 1948, the studio began premiering the nature documentary series, True-Life Adventures, which ran until 1960, winning 8 Academy Awards.[184][185] In 1949, the Walt Disney Music Company was founded to help with profits for merchandising.[186]

1950–1967: Live-action films, television, Disneyland, and Walt Disney's death

[edit]In the 1950s, Disney returned to producing full-length animated feature films, beginning with Cinderella (1950), the studio's first in 8 years. A critical and commercial success, Cinderella saved the studio after the financial pitfalls of the wartime era; it was Disney's most financially successful film since Snow White, making $8 million in its first year. Walt began to reduce his involvement with the studio's animation, focusing his attention on the company's increasingly diverse portfolio of projects including live-action films (of which Treasure Island was the studio's first), television and amusement parks.[187][188] In 1950 the company made its first foray into television when NBC aired "One Hour in Wonderland", a promotional program for Disney's next animated film, Alice in Wonderland (1951), and sponsored by Coca-Cola.[189] Alice was financially unsuccessful, falling $1 million short of the production budget.[190] In February 1953, Disney's next animated film Peter Pan was released to financial success;[191] it was the last Disney film distributed by RKO after Disney ended its contract and created its own distribution company Buena Vista Distribution.[192]

According to Walt, he first had the idea of building an amusement park during a visit to Griffith Park with his daughters. He said he watched them ride a carousel and thought there "should be ... some kind of amusement enterprise built where the parents and the children could have fun together".[193][194] Initially planning the construction of an eight-acre (3.2 ha) Mickey Mouse Park near the Burbank studio, Walt changed the planned amusement park's name to Disneylandia, then to Disneyland.[195] A new company, WED Enterprises (now Walt Disney Imagineering), was formed in 1952 to design and construct the park.[196] Drawing inspiration from amusement parks in the US and Europe, Walt approached the design of Disneyland with an emphasis on thematic storytelling and cleanliness, innovative approaches for amusement parks of the time.[197][198] The plan to build the park in Burbank was abandoned when Walt realized 8 acres would not be enough to accomplish his vision. Disney acquired 160 acres (65 ha) of orange groves in Anaheim, southeast of LA in neighboring Orange County, at $6,200 per acre to build the park.[199] Construction began in July 1954.

To finance the construction of Disneyland, Disney sold his home at Smoke Tree Ranch in Palm Springs and the company promoted it with a television series of the same name aired on ABC.[200] The Disneyland television series, which would be the first in a long-running series of successful anthology television programs for the company, was a success and garnered over 50% of viewers in its time slot, along with praise from critics.[201] In August, Walt formed another company Disneyland, Inc. to finance the park, whose construction costs totaled $17 million.[202]

In October, with the success of Disneyland, ABC allowed Disney to produce The Mickey Mouse Club, a variety show for children; the show included a daily Disney cartoon, a children's newsreel, and a talent show. It was presented by a host, and talented children and adults called "Mousketeers" and "Mooseketeers", respectively.[203] After the first season, over ten million children and five million adults watched it daily; and two million Mickey Mouse ears, which the cast wore, were sold.[204] In December 1954, the five-part miniseries Davy Crockett, premiered as part of Disneyland, starring Fess Parker. According to writer Neal Gabler, "[It] became an overnight national sensation", selling 10 million Crockett coonskin caps.[205] The show's theme song "The Ballad of Davy Crockett" became part of American pop culture, selling 10 million records. Los Angeles Times called it "the greatest merchandising fad the world had ever seen".[206][207] In June 1955, Disney's 15th animated film Lady and the Tramp was released and performed better at the box office than any other Disney films since Snow White.[208]

Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955; it was a major media event, broadcast live on ABC with actors Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings, and Ronald Reagan hosting. It garnered over 90 million viewers, becoming the most-watched live broadcast to that date.[209] While the park's opening day was disastrous (restaurants ran out of food, the Mark Twain Riverboat began to sink, other rides malfunctioned, and the drinking fountains were not working in the 100 °F. (38 °C) heat),[210][202] the park became a success with 161,657 visitors in its first week and 20,000 visitors a day in its first month. After its first year, 3.6 million people had visited, and after its second year, four million more guests came, making it more popular than the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Park. That year, the company earned a gross total of $24.5 million compared to the $11 million the previous year.[211]

Disney continued to delegate much of the animation work to the studio's top animators, known as the Nine Old Men. The company produced an average of five films per year throughout the 1950s and 60s.[212] Animated features of this period included Sleeping Beauty (1959), One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), and The Sword in the Stone (1963).[213] Sleeping Beauty was a financial loss for the company, and at $6 million, had the highest production costs up to that point.[214] One Hundred and One Dalmatians introduced an animation technique using the xerography process to electromagnetically transfer the drawings to animation cels, resulting in a transformed art style for the studio's animated films.[215] In 1956, the Sherman Brothers, Robert and Richard, were asked to produce a theme song for the television series Zorro.[216] The company hired them as exclusive staff songwriters, an arrangement that lasted 10 years. They wrote many songs for Disney's films and theme parks, and several were commercial hits.[217][218] In the late 1950s, Disney ventured into comedy with the live-action films The Shaggy Dog (1959), which became the highest-grossing film in the US and Canada for Disney at over $9 million,[219] and The Absent Minded Professor (1961), both starring Fred MacMurray.[213][220]

Disney also made live-action films based on children's books including Pollyanna (1960) and Swiss Family Robinson (1960). Child actor Hayley Mills starred in Pollyanna, for which she won an Academy Juvenile Award. Mills starred in 5 other Disney films, including a dual role as the twins in The Parent Trap (1961).[221][222] Another child actor, Kevin Corcoran, was prominent in many Disney live-action films, first appearing in a serial for The Mickey Mouse Club, where he would play a boy named Moochie. He worked alongside Mills in Pollyanna, and starred in features such as Old Yeller (1957), Toby Tyler (1960), and Swiss Family Robinson.[223] In 1964, the live action/animation musical film Mary Poppins was released to major commercial success and rapturous critical acclaim, becoming the year's highest-grossing film and winning five Academy Awards, including Best Actress for Julie Andrews as Poppins and Best Song for the Sherman Brothers', who also won Best Score for the film's "Chim Chim Cher-ee".[224][225]

Throughout the 1960s, Dean Jones, whom The Guardian called "the figure who most represented Walt Disney Productions in the 1960s", starred in 10 Disney films, including That Darn Cat! (1965), The Ugly Dachshund (1966), and The Love Bug (1968).[226][227] Disney's last child actor of the 1960s was Kurt Russell, who had signed a ten-year contract.[228] He featured in films such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969), The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit (1968) alongside Dean Jones, The Barefoot Executive (1971), and The Strongest Man in the World (1975).[229]

In late 1959, Walt had an idea to build another park in Palm Beach, Florida, called the City of Tomorrow, a city that would be full of technological improvements.[230] In 1964, the company chose land southwest of Orlando, Florida to build the park and acquired 27,000 acres (10,927 ha). On November 15, 1965, Walt, along with Roy and Florida's governor Haydon Burns, announced plans for a park called Disney World, which included Magic Kingdom—a larger version of Disneyland—and the City of Tomorrow, at the park's center.[231] By 1967, the company had made expansions to Disneyland, and more rides were added in 1966 and 1967, at a cost of $20 million.[232] The new rides included Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room, which was the first attraction to use Audio-Animatronics; Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress, which debuted at the 1964 New York World's Fair before moving to Disneyland in 1967; and Dumbo the Flying Elephant.[233]

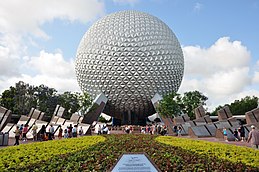

On November 20, 1964, Walt sold most of WED Enterprise to Walt Disney Productions for $3.8 million after being persuaded by Roy, who thought Walt having his own company would cause legal problems. Walt formed a new company called Retlaw to handle his personal business, primarily Disneyland Railroad and Disneyland Monorail.[234] When the company started looking for a sponsor for the project, Walt renamed the City of Tomorrow, Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (Epcot).[235] Walt, who had been a heavy smoker since World War I, fell very sick and he died on December 15, 1966, aged 65, of lung cancer, at St. Joseph Hospital across the street from the studio.[236][237]

1967–1984: Roy O. Disney's leadership and death, Walt Disney World, animation industry decline, and Touchstone Pictures

[edit]In 1967, the last two films Walt had worked on were released; the animated film The Jungle Book, which was Disney's most successful film for the next two decades, and the live-action musical The Happiest Millionaire.[238][239] After Walt's death, the company largely abandoned animation, but made several live-action films.[240][241] Its animation staff declined from 500 to 125 employees, with the company only hiring 21 people from 1970-77.[242]

Disney's first post-Walt animated film The Aristocats was released in 1970; according to Dave Kehr of Chicago Tribune, "the absence of his [Walt's] hand is evident".[243] The following year, the anti-fascist musical Bedknobs and Broomsticks was released and won the Oscar for Best Special Visual Effects.[244] At the time of Walt's death, Roy was ready to retire but wanted to keep Walt's legacy alive; he became the first CEO and chairman of the company.[245][246] In May 1967, Roy had legislation passed by Florida's legislatures to grant Disney World its own quasi-government agency in an area called Reedy Creek Improvement District. Roy changed Disney World's name to Walt Disney World to remind people it was Walt's dream.[247][248] EPCOT became less the City of Tomorrow, and more another amusement park.[249]

After 18 months of construction at a cost of around $400 million, Walt Disney World's first park the Magic Kingdom, along with Disney's Contemporary Resort and Disney's Polynesian Resort,[250] opened on October 1, 1971, with 10,400 visitors. A parade with over 1,000 band members, 4,000 Disney entertainers, and a choir from the US Army marched down Main Street. The icon of the park was the Cinderella Castle. On Thanksgiving Day, cars traveling to the Magic Kingdom caused traffic jams along interstate roads.[251][252]

On December 21, 1971, Roy died of cerebral hemorrhage at St. Joseph Hospital.[246] Donn Tatum, a senior executive and former president of Disney, became the first non-Disney-family-member to become CEO and chairman. Card Walker, who had been with the company since 1938, became its president.[253][254] By June 30, 1973, Disney had over 23,000 employees and a gross revenue of $257,751,000 over a nine-month period, compared to the year before when it made $220,026,000.[255] In November, Disney released the animated film Robin Hood (1973), which became Disney's biggest international-grossing movie at $18 million.[256] Throughout the 1970s, Disney released live-action films such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes' sequel Now You See Him, Now You Don't;[257] The Love Bug sequels Herbie Rides Again (1974) and Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo (1977);[258][259] Escape to Witch Mountain (1975);[260] and Freaky Friday (1976).[261] In 1976, Card Walker became CEO of the company, with Tatum remaining chairman until 1980, when Walker replaced him.[245][254] In 1977, Roy E. Disney, Roy O. Disney's son and the only Disney working for the company, resigned as an executive because of disagreements with company decisions.[262]

In 1977, Disney released the successful animated film The Rescuers, which grossed $48 million.[263] The live-acton/animated musical Pete's Dragon was released in 1977, grossing $16 million in the US and Canada, but was a disappointment to the company.[264][265] In 1979, Disney's first PG-rated film and most expensive film to that point at $26 million The Black Hole was released, showing Disney could use special effects. It grossed $35 million, a disappointment to the company, which thought it would be a hit like Star Wars (1977). The Black Hole was a response to other Science fiction films of the era.[266][267]

In September, 12 animators, which was over 15% of the department, resigned. Led by Don Bluth, they left because of a conflict with the training program and the atmosphere, and started their own company Don Bluth Productions.[268][269] In 1981, Disney released Dumbo to VHS and Alice in Wonderland the following year, leading Disney to eventually release all its films on home media.[270] On July 24, Walt Disney's World on Ice, a two-year tour of ice shows featuring Disney charters, made its premiere at the Brendan Byrne Meadowlands Arena after Disney licensed its characters to Feld Entertainment.[271][272] The same month, Disney's animated film The Fox and the Hound was released and became the highest-grossing animated film to that point at $40 million.[273] It was the first film that did not involve Walt and the last major work done by Disney's Nine Old Men, who were replaced with younger animators.[242]

As profits started to decline, on October 1, 1982, Epcot, then known as EPCOT Center, opened as the second theme park in Walt Disney World, with around 10,000 people in attendance during the opening.[274][275] The park cost over $900 million to construct, and consisted of the Future World pavilion and World Showcase representing Mexico, China, Germany, Italy, America, Japan, France, the UK, and Canada; Morocco and Norway were added in 1984 and 1988, respectively.[274][276] The animation industry continued to decline and 69% of the company's profits were from its theme parks; in 1982, there were 12 million visitors to Walt Disney World, a figure that declined by 5% the following June.[274] On July 9, 1982, Disney released Tron, one of the first films to extensively use computer-generated imagery (CGI). It was a big influence on other CGI movies, though it received mixed reviews.[277] In 1982, the company lost $27 million.[278]

On April 15, 1983, Disney's first park outside the US, Tokyo Disneyland, opened in Urayasu.[279] Costing around $1.4 billion, construction started in 1979 when Disney and The Oriental Land Company agreed to build a park together. Within its first ten years, the park had over 140 million visitors.[280] After an investment of $100 million, on April 18, Disney started a pay-to-watch cable television channel called Disney Channel, a 16-hours-a-day service showing Disney films, twelve programs, and two magazines shows for adults. Although it was expected to do well, the company lost $48 million after its first year, with around 916,000 subscribers.[281][282]

In 1983, Walt's son-in-law Ron W. Miller, who had been president since 1978, became its CEO, and Raymond Watson became chairman.[245][283] Miller wanted the studio to produce more content for mature audiences,[284] and Disney founded film distribution label Touchstone Pictures to produce movies geared toward adults and teenagers in 1984.[278] Splash (1984) was the first film released under the label, and a much-needed success, grossing over $6 million in its first week.[285] Disney's first R-rated film Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) was released and was another hit, grossing $62 million.[286] The following year, Disney's first PG-13 rated film Adventures in Babysitting was released.[287] In 1984, Saul Steinberg attempted to buy out the company, holding 11% of the stocks. He offered to buy 49% for $1.3 billion or the entire company for $2.75 billion. Disney, which had less than $10 million, rejected Steinberg's offer and offered to buy all of his stock for $326 million. Steinberg agreed, and Disney paid it all with part of a $1.3 billion bank loan, putting the company $866 million in debt.[288][289]

1984–2005: Michael Eisner's leadership, the Disney Renaissance, merger, and acquisitions

[edit]

In 1984, shareholders Roy E. Disney, Sid Bass, Lillian and Diane Disney, and Irwin L. Jacobs—who together owned about 36% of the shares, forced out CEO Miller and replaced him with Michael Eisner, a former president of Paramount Pictures, and appointed Frank Wells as president.[290] Eisner's first act was to make it a major film studio, which at the time it was not considered. Eisner appointed Jeffrey Katzenberg as chairman and Roy E. Disney as head of animation. Eisner wanted to produce an animated film every 18 months rather than four years, as the company had been doing. To help with the film division, the company started making Saturday-morning cartoons to create new Disney characters for merchandising, and produced films through Touchstone. Under Eisner, Disney became more involved with television, creating Touchstone Television and producing the television sitcom The Golden Girls, which was a hit. The company spent $15 million promoting its theme parks, raising visitor numbers by 10%.[291][292] In 1984, Disney produced The Black Cauldron, then the most-expensive animated movie at $40 million, their first animated film to feature computer-generated imagery, and their first PG-rated animation because of its adult themes. The film was a box-office failure, leading the company to move the animation department from the studio in Burbank to a warehouse in Glendale, California.[293] The film-financing partnership Silver Screen Partners II, which was organized in 1985, financed films for Disney with $193 million. In January 1987, Silver Screen Partners III began financing movies for Disney with $300 million raised by E.F. Hutton, the largest amount raised for a film-financing limited partnership.[294] Silver Screen IV was also set up to finance Disney's studios.[295]

In 1986, the company changed its name from Walt Disney Productions to the Walt Disney Company, stating the old name only referred to the film industry.[296] With Disney's animation industry declining, the animation department needed its next movie The Great Mouse Detective to be a success. It grossed $25 million at the box office, becoming a much-needed financial success.[297] To generate more revenue from merchandising, the company opened its first retail store Disney Store in Glendale in 1987. Because of its success, the company opened two more in California, and by 1990, it had 215 throughout the US[298][299] In 1989, the company garnered $411 million in revenue and made a profit of $187 million.[300] In 1987, the company signed an agreement with the Government of France to build a resort named Euro Disneyland in Paris; it would consist of two theme parks named Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park, a golf course, and 6 hotels.[301][302]

In 1988, Disney's 27th animated film Oliver & Company was released the same day as that of former Disney animator Don Bluth's The Land Before Time. Oliver & Company out-competed The Land Before Time, becoming the first animated film to gross over $100 million in its initial release, and the highest-grossing animated film in its initial run.[303][304] Disney became the box-office-leading Hollywood studio for the first time, with films such as Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Three Men and a Baby (1987), and Good Morning, Vietnam (1987). The company's gross revenue went from $165 million in 1983 to $876 million in 1987, and operating income went from −$33 million in 1983 to +130 million in 1987. The studio's net income rose by 66%, along with a 26% growth in revenue. Los Angeles Times called Disney's recovery "a real rarity in the corporate world".[305] On May 1, 1989, Disney opened Disney-MGM Studios, its third amusement park at Walt Disney World, and later became Hollywood Studios. The new park demonstrated to visitors the movie-making process, until 2008, when it was changed to make guests feel they are in movies.[306] Following the opening of Disney-MGM Studios, Disney opened the water park Typhoon Lagoon in June 1989; in 2022 it had 1.9 million visitors and was the most popular water park in the world.[307][308] Also in 1989, Disney signed an agreement-in-principle to acquire The Jim Henson Company from its founder. The deal included Henson's programming library and Muppet characters—excluding the Muppets created for Sesame Street—as well as Henson's personal creative services. Henson, however, died in May 1990 before the deal was completed, resulting in the companies terminating merger negotiations.[309][310][311]

On November 17, 1989, Disney released The Little Mermaid, which was the start of the Disney Renaissance, a period in which the company released hugely successful and critically acclaimed animated films. The Little Mermaid became the animated film with the highest gross from its initial run and garnered $233 million at the box office; it won two Academy Awards; Best Original Score and Best Original Song for "Under the Sea".[312][313] During the Disney Renaissance, composer Alan Menken and lyricist Howard Ashman wrote several Disney songs until Ashman died in 1991. Together they wrote 6 songs nominated for Academy Awards; with two winning songs—"Under the Sea" and "Beauty and the Beast".[314][315] To produce music geared for the mainstream, including music for movie soundtracks, Disney founded the recording label Hollywood Records on January 1, 1990.[316][317] In September 1990, Disney arranged for financing of up to $200 million by a unit of Nomura Securities for Interscope films made for Disney. On October 23, Disney formed Touchwood Pacific Partners, which replaced the Silver Screen Partnership series as the company's movie studios' primary source of funding.[295] Disney's first animated sequel The Rescuers Down Under was released on November 16, 1990, and created using Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), digital software developed by Disney and Pixar—the computer division of Lucasfilm—becoming the first feature film to be entirely created digitally.[313][318] Although the film struggled in the box office, grossing $47 million, it received positive reviews.[319][320] In 1991, Disney and Pixar agreed to a deal to make three films together, the first one being Toy Story.[321]

Dow Jones & Company, wanting to replace 3 companies in its industrial average, chose to add Disney in May 1991, stating Disney "reflects the importance of entertainment and leisure activities in the economy".[322] Disney's next animated film Beauty and the Beast was released on November 13, 1991, and grossed nearly $430 million.[323][324] It was the first animated film to win a Golden Globe for Best Picture, and it received 6 Academy Award nominations, becoming the first animation nominated for Best Picture; it won Best Score, Best Sound, and Best Song.[325] The film was critically acclaimed, with some critics considering it to be the best Disney film.[326][327] To coincide with the 1992 release of The Mighty Ducks, Disney founded the National Hockey League team The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim.[328] Disney's next animated feature Aladdin was released on November 11, 1992, and grossed $504 million, becoming the highest-grossing animated film to that point, and the first animated film to gross a half-billion dollars.[329][330] It won two Academy Awards—Best Song for "A Whole New World" and Best Score;[331] and "A Whole New World" was the first-and-only Disney song to win the Grammy for Song of the Year.[332][333] For $60 million, Disney broadened its range of mature-audience films by acquiring independent film distributor Miramax Films in 1993.[334] The same year, in a venture with The Nature Conservancy, Disney purchased 8,500 acres (3,439 ha) of Everglades headwaters in Florida to protect native animals and plant species, establishing the Disney Wilderness Preserve.[335]

On April 3, 1994, Frank Wells died in a helicopter crash; he, Eisner, and Katzenberg helped the company's market value go from $2 billion to $22 billion since taking office in 1984.[336] On June 15 the same year, The Lion King was released and was a massive success, becoming the second-highest-grossing film of all time behind Jurassic Park and the highest-grossing animated film of all time, with a gross total of $969 million.[337][338] It was critically praised and garnered two Academy Awards—Best Score and Best Song for "Can You Feel the Love Tonight".[339][340] Soon after its release, Katzenberg left the company after Eisner refused to promote him to president. After leaving, he co-founded film studio DreamWorks SKG.[341] Wells was later replaced with one of Eisner's friends Michael Ovitz on August 13, 1995.[342][343] In 1994, Disney wanted to buy one of the major U.S. television networks ABC, NBC, or CBS, which would give the company guaranteed distribution for its programming. Eisner planned to buy NBC but the deal was canceled because General Electric wanted to keep a majority stake.[344][345] In 1994, Disney's annual revenue reached $10 billion, 48% coming from film, 34% from theme parks, and 18% from merchandising. Disney's total net income was up 25% from the previous year at $1.1 billion.[346] Grossing over $346 million, Pocahontas was released on June 16, garnering the Academy Awards for Best Musical or Comedy Score and Best Song for "Colors of the Wind".[347][348] Pixar's and Disney's first co-release was the first-ever fully computer-generated film Toy Story, which was released on November 19, 1995, to critical acclaim and an end-run gross total of $361 million. The film won the Special Achievement Academy Award and was the first animated film to be nominated for Best Original Screenplay.[349][350]

In 1995, Disney announced the $19 billion acquisition of television network Capital Cities/ABC Inc., which was then the 2nd-largest corporate takeover in US history. Through the deal, Disney would obtain broadcast network ABC, an 80% majority stake in sports networks ESPN and ESPN 2, 50% in Lifetime Television, a majority stake of DIC Entertainment, and a 38% minority stake in A&E Television Networks.[346][351][352] Following the deal, the company started Radio Disney, a youth-focused radio program on ABC Radio Network, on November 18, 1996.[353][354] The Walt Disney Company launched its official website disney.com on February 22, 1996, mainly to promote its theme parks and merchandise.[355] On June 19, the company's next animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame was released, grossing $325 million at the box office.[356] Because Ovitz's management style was different from Eisner's, Ovitz was fired as the company's president in 1996.[357] Disney lost a $10.4 million lawsuit in September 1997 to Marsu B.V. over Disney's failure to produce as contracted 13 half-hour Marsupilami cartoon shows. Instead, Disney felt other internal "hot properties" deserved the company's attention.[358] Disney, which since 1996 had owned a 25% stake in the Major League Baseball team California Angels, bought out the team in 1998 for $110 million, renamed it Anaheim Angels and renovated the stadium for $100 million.[359][360] Hercules (1997) was released on June 13, and underperformed compared to earlier films, grossing $252 million.[361] On February 24, Disney and Pixar signed a ten-year contract to make five films, with Disney as distributor. They would share the cost, profits, and logo credits, calling the films Disney-Pixar productions.[362] During the Disney Renaissance, film division Touchstone also saw success with film such as Pretty Woman (1990), which has the highest number of ticket sales in the U.S. for a romantic comedy and grossed $432 million;[363][364] Sister Act (1992), which was one of the financially successful comedies of the early 1990s, grossing $231 million;[365] action film Con Air (1997), which grossed $224 million;[366] and the highest-grossing film of 1998 at $553 million Armageddon.[367]

At Disney World, the company opened Disney's Animal Kingdom, the largest theme park in the world covering 580 acres (230 ha) on Earth Day, April 22, 1998. It had six animal-themed lands, over 2,000 animals, and the Tree of Life at its center.[368][369] Receiving positive reviews, Disney's next animated films Mulan and Disney-Pixar film A Bug's Life were released on June 5 and November 20, 1998.[370][371] Mulan became the year's sixth-highest-grossing film at $304 million, and A Bug's Life was the year's fifth-highest at $363 million.[367] In a $770-million transaction, on June 18, Disney bought a 43% stake of Internet search engine Infoseek for $70 million, also giving it Infoseek-acquired Starwave.[372][373] Starting web portal Go.com in a joint venture with Infoseek in January 1999, Disney acquired the rest of Infoseek later that year.[374][375] After unsuccessful negotiations with cruise lines Carnival and Royal Caribbean International, in 1994, Disney announced it would start its own cruise-line operation in 1998.[376][377] The first two ships of the Disney Cruise Line were named Disney Magic and Disney Wonder, and built by Fincantieri in Italy. To accompany the cruises, Disney bought Gorda Cay as the line's private island, and spent $25 million remodeling it and renaming it Castaway Cay. On July 30, 1998, Disney Magic set sail as the line's first voyage.[378]

Marking the end of the Disney Renaissance, Tarzan (1999) was released on June 12, garnering $448 million at the box office and critical acclaim; it claimed the Academy Award for Best Original Song for Phil Collins' "You'll Be in My Heart".[379][380][381][382] Disney-Pixar film Toy Story 2 was released on November 13, garnering praise and $511 million at the box office.[383][384] To replace Ovitz, Eisner named ABC network chief Bob Iger Disney's president and chief operating officer in January 2000.[385][386] In November, Disney sold DIC Entertainment back to Andy Heyward.[387] Disney had another huge success with Pixar when they released Monsters, Inc. in 2001. Later, Disney bought children's cable network Fox Family Worldwide for $3 billion and the assumption of $2.3 billion in debt. The deal included a 76% stake in Fox Kids Europe, Latin American channel Fox Kids, more than 6,500 episodes from Saban Entertainment's programming library, and Fox Family Channel.[388] In 2001, Disney's operations had a net loss of $158 million after a decline in viewership of the ABC television network, as well as decreased tourism due to the September 11 attacks. Disney earnings in fiscal 2001 were $120 million compared with the previous year's $920 million. To help reduce costs, Disney announced it would lay off 4,000 employees and close 300-400 Disney stores.[389][390] After winning the World Series in 2002, Disney sold the Anaheim Angels for $180 million in 2003.[391][392] In 2003, Disney became the first studio to garner $3 billion in a year at the box office.[393] The same year, Roy Disney announced his retirement because of how the company was being run, calling on Eisner to retire; the same week, board member Stanley Gold retired for the same reasons. Gold and Disney formed the "Save Disney" campaign.[394][395]