User:SomeGuyWhoRandomlyEdits/Early Dynastic I

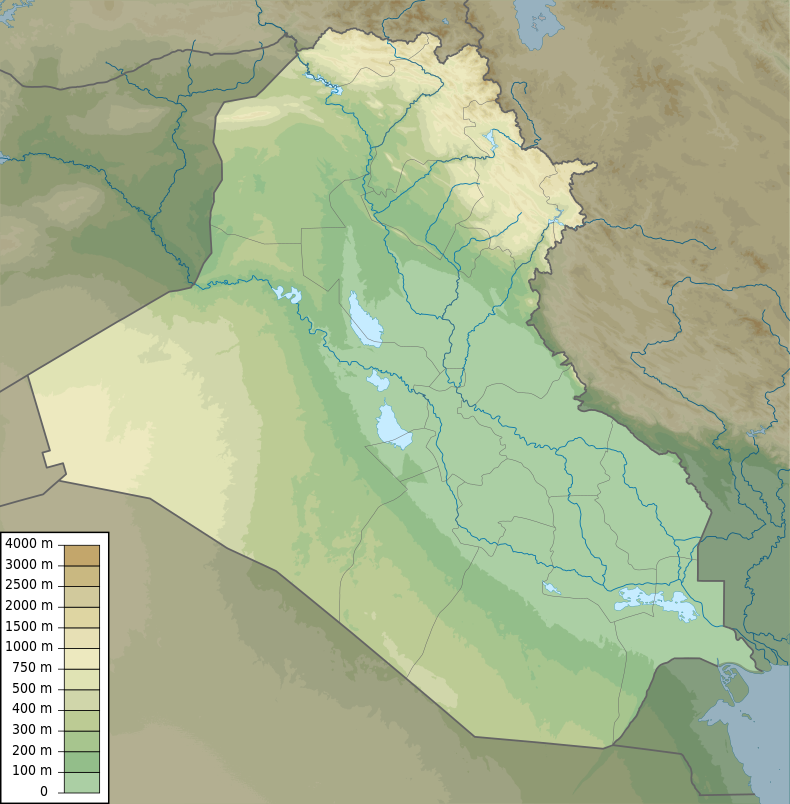

A map detailing the locations of various archaeological sites, ancient hamlets, villages, towns, and/or city-states occupied by the archaeological culture of ED I. | |

| Alternative names | ED I period or ED I |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Lower Mesopotamia |

| Period | Early Dynastic |

| Dates | c. 2900 – c. 2750/2700 BCE |

| Preceded by | Jemdet Nasr period |

| Followed by | Early Dynastic II period |

| Defined by | Henri Frankfort |

The Early Dynastic I period (abbreviated ED I period or ED I) is the first out of two, three, or even up to four sub-periods to an archaeological culture of Mesopotamia referred to as the Early Dynastic (ED). The terms for the preceding Ubaid, Uruk, and Jemdet Nasr periods to go with the ED were coined by archaeologists at a conference in Baghdad during the 1930s. The ED was divided into the following sub-periods: ED I, II, and III. Depending on which chronological timeline for the Ancient Near East (ANE) is preferred among the present-day general consensus of mainstream historians, the ED I period is usually said to have begun after a cultural break with the preceding Jemdet Nasr period that has been radiocarbon dated to either c. 2900 BCE by the Middle Chronology (MC), or c. 2800 BCE by the Short Chronology (SC); then, gradually transitioning into ED II c. 2750/2700 BCE (MC), or even up to c. 2600 BCE (SC). The exact dating of the ED sub-periods has varied between scholars—some abandoning the ED II in order to allow ED III begin earlier so that ED III can be said to have immediately followed ED I (going so far as to using only Early ED and Late ED in their stead). The MC is commonly encountered in literature, including many current textbooks on the archaeology and/or history of the ANE.

In lower Mesopotamia, the ED I shared characteristics with the Late and Final Uruk phases (c. 3300 – c. 2900 BCE) and Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE).[1] While many historical time periods of the ANE have been named after the great power of their respective time (e.g. the Akkadian and Ur III periods); this does not apply to the ED I. The ED I is an archaeological sub-period that does not reflect political developments and is based primarily upon perceived changes in the archaeological record (e.g. pottery and glyptics); for example, the narrow ED I cylinder seals are distinguishable from the broader and wider ED II seals (which are engraved with banquet and/or animal-contest scenes).[2]

Sumerian cities (in a chronological order starting with the first believed to have been settled and/or founded) such as: Eridu, Nippur, Uruk, Girsu, Ur, Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak were all very powerful and/or influential at their respective peaks all throughout lower Mesopotamia. Further to the north near and/or into the middle- or upper- reaches of Mesopotamia stretched East Semitic states centered on settlements such as Kish, Mari, and Nagar. To the east there may have laid the proto-Elamite polities of Susa, Anshan, Hamazi, Aratta, and/or Marhasi.

The ED I saw the development of writing; although, its contemporary sources (or lack thereof) do not allow for an easy reconstruction of a political history. There are no (or almost none) contemporary documents shedding any light on warfare or diplomacy during the ED I; also, no inscriptions have been found (with absolute certainty) verifying any names of rulers that may be associated with texts from this period.

Ethnic groups and languages

[edit]Sumerians

[edit]Most historians have suggested that Sumer was first permanently settled (c. 5500 – c. 3300 BCE) by a west Asian people who spoke Sumerian; however, the ethnic composition of Mesopotamia throughout the Ubaid, Uruk, and/or ED I period(s) cannot be determined with certainty. It is connected to the problem of the origins of the Sumerians in lower Mesopotamia and the dating of their emergence (assuming that they were thought of as natives), or their arrival (assuming that they were thought of as foreigners). There is no agreement on the archaeological evidence for a migration, or on whether the earliest form of writing already reflects a specific language. Some argue that it is actually Sumerian (in which case the Sumerians would have been its inventors), and would have already been present in the region by the final centuries of the fourth millennium BCE. Whether or not other ethnic groups were also present—especially the East Semitic ancestors of the Akkadians and/or one or several pre-Sumerian peoples—is also debated and cannot be resolved easily by excavation alone.

Ever since the decipherment of the Sumerian cuneiform script; it has been the subject of much effort to relate it to a wide variety of languages. Proposals for linguistic affinity sometimes have a nationalistic background because it has a peculiar prestige as one of the most ancient written languages. Such proposals enjoy virtually no support among linguists because of their unverifiability.

Other scholars think that the Sumerian language may have originally been that of the hunting and fishing peoples who lived in the Mesopotamian Marshes and the Eastern Arabia littoral region; additionally, were part of the Arabian bifacial culture. Some archaeologists believe that the Sumerians lived along the Persian gulf coast of the Arabian peninsula before a flood at the end of Last Glacial Period c. 10000 – c. 8000 BCE. Many scholars have proposed historical and genetic links between the present-day Marsh Arabs and the Sumerians of ancient Iraq based off of: their methods for house-building (mudhifs), homeland (Mesopotamian Marshes), and shared agricultural practices; however, there is no written record of the marsh tribes until the ninth century CE—and the Sumerians had already lost their distinct ethnic identity some 2,700 years prior.

Others have suggested that the Sumerians migrated from North Africa (during the Green Saharan period) into West Asia and were responsible for the spread of farming throughout the Fertile Crescent. Although not specifically discussing Sumerians, researchers have suggested a partial North African origin for some pre-Semitic cultures of the Near East (particularly Natufians) after testing the genomes of Natufian and Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture-bearers; alternatively, a genetic analysis of four ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA samples suggests an association of the Sumerians with the inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization (possibly as a result of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations). Sumerians (or at least some of them) may have been related to the original Dravidian population of India.

Ubaidians

[edit]Some have argued that by examining the structure of the Sumerian language, its names for occupations; as well as toponyms and hydronyms, one can suggest that there was once an ethnic group in the region that preceded the Sumerians. These pre-Sumerian people are now referred to as Proto-Euphrateans (or Ubaidians), and are theorized to have developed out of the culture centered at the Samarra Archaeological City (c. 6200 – c. 4700 BCE). The Ubaid culture spread into northern Mesopotamia and was adopted by the Halaf culture c. 5000 BCE. This is known as the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period of northern Mesopotamia.

Proto-Euphratean is considered by some to have been the substratum language of the people that introduced farming into southern Mesopotamia during the Early Ubaid period (c. 5300 – c. 4700 BCE). Proto-Euphratean may have exerted an areal influence on it (especially in the form of polysyllabic words that sound un-Sumerian)—making researchers suspect them of being loanwords—and untraceable to any other known language. There is little speculation as to the affinities of this substratum language; therefore, it remains unclassified. A related proposal is that the language of the proto-literary texts from the Late Uruk period (c. 3350 – c. 3100 BC) is really an early Indo-European language termed Euphratic. Sumerian was once widely held to be an Indo-European language; but, that view later came to be almost universally rejected. It has also been suggested that Sumerian descended from a late prehistoric creole language.

Semites

[edit]A Bayesian analysis suggested an origin for all known Semitic languages with a population of ancient Semitic-speaking peoples migrating from the Levant c. 3750 BCE; furthermore, spreading into Mesopotamia and possibly contributing to the collapse of the Uruk period c. 3100 BCE.[3] Kish has been identified as the center of the earliest known East Semitic culture (the Kish civilization).[4] This early East Semitic culture is characterized by linguistic, literary, and orthographic similarities extending across settlements such as Mari, Nagar, Abu Salabikh, and Ebla.[5][4]

The similarities include the use of a writing system that contained non-Sumerian logograms, the use of the same system in naming the months of the year, dating by regnal years, and a measuring system (among many others).[4] However, the existence of a single authority ruling those lands has not been assumed as each city had its own monarchical system, in addition to some linguistic differences for while the languages of Mari and Ebla were closely related, Kish represented an independent East Semitic linguistic entity that spoke a sort of dialect (Kishite), different from that of both the pre-Sargonic Akkadian and Eblaite languages.[6][4] The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages, and is attested by three distinct languages: Kishite, Akkadian, and Eblaite (all of which have been long extinct). Kishite is the oldest known Semitic language.[6][4][7][5][8][3]

Throughout the third millennium BCE, an intimate cultural symbiosis developed between Sumerians and Semites (which included widespread bilingualism). The influence of the Sumerian and East Semitic languages on each other is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a substantial scale to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and the East Semitic languages during the third millennium BCE as a sprachbund.

Elamites

[edit]Earliest city-states

[edit]Permanent year-round urban settlement may have been prompted by intensive agricultural practices. The work required in maintaining irrigation canals called for, and the resulting surplus food enabled, relatively concentrated populations. The centers of Eridu and Uruk, two of the earliest cities, had successively elaborated large temple complexes built out of mudbrick. Developing as small shrines with the earliest settlements, by the ED I period, they had become the most imposing structures in their respective cities, each dedicated to its own tutelary deity.

| Settlement's ancient name | Principal temple complex | Tutelary deity | Archaeological site's modern Arabic name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eridu | Eabzu | Enki | Tell Abu Shahrain |

| Kuara | Ekishnugal | Nergal | Tell al-Lahm |

| Ur | Ekishnugal | Nannar | Tell al-Muqayyar |

| Uruk | Eanna | An | Tell al-Warka |

| Bad-tibira | Emush | Dumuzid | Tell al-Madain |

| Girsu | Ekuninazag | Ningirsu | Tell Telloh |

| Umma | Emah | Shara |

|

| Zabala | Ezikalamma | Inanna | Tell Ibzeikh |

| Nippur | Ekur | Enlil | Tell Nuffar |

| Isin | Enidubbi | Nintinugga | Ishan al-Bahriyat |

| Shuruppak | Edimgalanna | Sud | Tell Fara |

| Eresh | ? | Baal | Tell Abu Salabikh? |

| Larak | ? | Pabilsaĝ | ? |

| Kish | Edub | Ninhursag |

|

| Sippar | Ebabbar | Utu | Tell Abu Habbah |

| Akshak | ? | ? | ? |

| Tutub | Temple of Nintu | Nintu | Tell Khafajah |

| Eshnunna | Esikil | Ninazu | Tell Asmar |

Religion and literature

[edit]Sumerian King List

[edit] The SKL inscribed onto the Weld-Blundell Prism (WB444). | |

| Author | Berossus (only the author of one of the much later copies) |

|---|---|

| Original title | 𒉆𒈗 |

| Translator |

|

| Language | Sumerian |

| Subject | Regnal list |

| Genre | Literary |

| Set in | c. 3500 – c. 1600 BCE |

Publication date | c. 1900 – c. 1600 BCE |

| Publication place | Sumer (ancient Iraq) |

Published in English | 1939 – 2014 CE |

| Media type | Clay tablets |

| Text | Sumerian King List at the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature |

The Sumerian King List (SKL) is an ancient regnal list written using cuneiform script, listing: the kings of Sumer, their supposed reign lengths, and the locations of kingship. This text is preserved in several recensions. The list of kings is sequential; although, modern research has indicated that many were contemporaries–reflecting the belief that kingship was handed down by the gods and could be transferred from one city to another–asserting to a hegemony in the region.[10] The SKL is important to the chronology of the ANE for the third millennium BCE. However, the fact that many of the listed dynasties reigned simultaneously from varying localities makes it difficult to reproduce a strict linear chronology.

Most of the dates for the predynastic kings have been approximated to certain centuries (rather than specific years), and are only partially based on any available archaeological data. For most kings listed, the SKL is itself the lone source of information. The SKL initially (and presumably) mixes mythical, predynastic kings enjoying implausibly lengthy reigns; then, gradually working its way into the more plausible, historical dynasties. Although the primal kings are historically unattested, this does not necessarily preclude their possible correspondence with the historical (some of which may have later been mythicized, deified, and/or demonized). Some Assyriologists think of the primal monarchs as fictional characters that were invented several centuries and/or even millennia after their purported reigns.

While there is no evidence that they ever reigned as such, the Sumerians purported the predynastic kings to have lived in a mythical era before a flood. None of the antediluvian kings have been verified as being historical through archaeological excavations, epigraphical inscriptions, or otherwise. The antediluvian reigns were measured using two Sumerian numerical units (a sexagesimal system). There were "sars" (units of 3,600 years each) and "ners" (units of 600 years). Attempts have been made to map these numbers into more reasonable regnal lengths.

Predynastic period

[edit]After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu. In Eridu, Alulim[a] became king;[b] he ruled for 28,800 years. Alalngar ruled for 36,000 years. 2 kings; they ruled for 64,800 years. Then Eridu fell and the kingship was taken to Bad-tibira. In Bad-tibira, En-men-lu-ana ruled for 43,200 years. En-men-gal-ana ruled for 28,800 years. Dumuzid, the Shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years. 3 kings; they ruled for 108,000 years. Then Bad-tibira fell and the kingship was taken to Larak. In Larak, En-sipad-zid-ana ruled for 28,800 years. 1 king; he ruled for 28,800 years. Then Larak fell and the kingship was taken to Sippar. In Sippar, En-men-dur-ana became king; he ruled for 21,000 years. 1 king; he ruled for 21,000 years. Then Sippar fell and the kingship was taken to Shuruppak. In Shuruppak, Ubara-Tutu became king; he ruled for 18,600 years. 1 king; he ruled for 18,600 years. In 5 cities 8 kings; they ruled for 241,209 years. Then the flood swept over.

— SKL

As these kings were said on the SKL to have reigned implausibly lengthy reigns (8 kings ruled for up to 241,209 years), their reigns can be reduced (down to 67 years). Assuming that they were not purely fictional kings, they may have ruled at some point during the 30th and/or 29th centuries BCE.[11] Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak may have each had anywhere from 10,000—20,000 citizens by the ED I.[12]

The Sumerians claimed that their civilization had been brought—fully formed—to the city of Eridu by one of their gods (Enki) or by his advisor (Adapa). Eridu was a settlement founded during the Eridu phase of the Ubaid period (c. 5400 – c. 4700 BCE) and may have been abandoned during the Late Ubaid/Early Uruk period (c. 4200 – c. 3700 BCE).[12] Eridu is named as the city of the first kings on the SKL and was long considered the earliest city in lower Mesopotamia. The settlement of Eridu may have been at the confluence of three separate ecosystems from where three peoples (each with distinct cultures and/or lifestyles) came to an agreement about access to fresh water in a desert environment. Eridu had already recovered by the EDI (c. 2900 – c. 2700 BCE) and may have had anywhere from 4,000—20,000 citizens.[12] It was abandoned again sometime during the Neo-Babylonian period (626 – 539 BCE).

The Uruk List of Kings and Sages (ULKS) pairs seven antediluvian kings each with his own apkallu. An apkallu was a sage in Sumerian literature and/or religion. The first apkallu (Adapa) is paired up with Alulim. Adapa has been compared with the Biblical figure Adam. The ULKS lists another eight (postdivulian) kings also paired up with apkallu.

Dumuzid[c] is listed on the SKL twice as an antediluvian king of both Bad-tibira and Uruk. He may have been posthumously deified and has been identified with the god Ama-ušumgal-ana (who was originally the tutelary deity worshipped in the city Lagash). The E-mush temple of Bad-tibira was originally dedicated to Dumuzid when it was built before being re-dedicated to Lulal when the goddess Inanna appointed Lulal god of the city. He was the protagonist in the Dream of Dumuzid and Dumuzid and Geshtinanna. He was also mentioned in Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, Inanna Prefers the Farmer, and Inanna and Bilulu.

The name of En-men-dur-ana means "chief of the powers of Dur-an-ki", while Dur-an-ki, in turn, means: "the meeting-place of heaven and earth" (literally: "bond of above and below"). The ULKS pairs him up with the apkallu Utuabzu. He has been compared with the Biblical patriarch Enoch. A myth written in a Semitic language tells of En-men-dur-ana being taken to heaven by the gods Shamash and Adad, and taught the secrets of heaven and of earth.

History

[edit]First dynasty of Kish

[edit]First dynasty of Kish | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2900 BCE–c. 2500 BCE | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | In exile (c. 2670 BCE – c. 2570 BCE) | ||||||||

| Capital | Kish | ||||||||

| Common languages | Kishite and Sumerian | ||||||||

| Religion | Sumerian religion | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Kishite | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Lugal Kiški | |||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Jushur | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Kullassina-bel | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Nangishlishma | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | En-tarah-ana | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Babum | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Puannum | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Kalibum | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Kalumum | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Zuqaqip | ||||||||

• c. 2900 BCE | Arwium | ||||||||

• c. 2800 – c. 2750 BCE | Etana | ||||||||

• c. 2750 – c. 2700 BCE | Enmebaragesi | ||||||||

• c. 2700 – c. 2670 BCE | Aga | ||||||||

• c. 2570 – c. 2550 BCE | Uhub | ||||||||

• c. 2550 – c. 2500 BCE | Mesilim | ||||||||

| En | |||||||||

• c. 2775 – c. 2750 BCE | Meshkiangasher | ||||||||

• c. 2750 – c. 2730 BCE | Enmerkar | ||||||||

• c. 2730 – c. 2700 BCE | Lugalbanda | ||||||||

• c. 2700 BCE | Dumuzid | ||||||||

• c. 2700 – c. 2650 BCE | Gilgamesh | ||||||||

| Ensi | |||||||||

• c. 2550 BCE | Nin-kisalsi | ||||||||

• c. 2510 – c. 2494 BCE | Lugalshaengur | ||||||||

| Legislature | Ukkin | ||||||||

• Ehursag | Ekur | ||||||||

• É | E-dub | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Flood | c. 2900 BCE | ||||||||

• Established | c. 2900 BCE | ||||||||

| c. 2750 – c. 2700 BCE | |||||||||

| c. 2700 – c. 2670 BCE | |||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 2500 BCE | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| c. 2800 BCE | 10,000[13] km2 (3,900 sq mi) | ||||||||

| c. 2500 BCE | 30,000[13] km2 (12,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• c. 2800 BCE | 40,000[12] | ||||||||

• c. 2500 BCE | 25,000[12] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of Iraq | ||||||||

After the flood had swept over, and the kingship had descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish. In Kish, Jushur became king; he ruled for 1,200 years. Kullassina-bel ruled for 960 years. Nangishlishma ruled for 670 years. En-tarah-ana ruled for 420 years, 3 months, and 3½ days. Babum ruled for 300 years. Puannum ruled for 840 years. Kalibum ruled for 960 years. Kalumum ruled for 840 years. Zuqaqip ruled for 900 years. Atab ruled for 600 years. Mashda, the son of Atab, ruled for 840 years. Arwium, the son of Mashda, ruled for 720 years. Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries, became king; he ruled for 1,500 years. Balih, the son of Etana, ruled for 400 years. En-me-nuna ruled for 660 years. Melem-Kish, the son of En-me-nuna, ruled for 900 years. 1,560 are the years of the dynasty of En-me-nuna. Barsal-nuna, the son of En-me-nuna, ruled for 1,200 years. Zamug, the son of Barsal-nuna, ruled for 140 years. Tizqar, the son of Zamug, ruled for 305 years. Ilku ruled for 900 years. Iltasadum ruled for 1,200 years. Enmebaragesi, who made the land of Elam submit, became king; he ruled for 900 years. Aga, the son of Enmebaragesi, ruled for 625 years. 1,525 are the years of the dynasty of Enmebaragesi. 23 kings; they ruled for 24,510 years, 3 months, and 3½ days. Then Kish was defeated and the kingship was taken to Eanna.

— SKL

Kish may have held the hegemony over the entire territory of northern and central Mesopotamia (including cities such as Tutub and Tell Agrab) along with the most northernly section of southern Mesopotamia (including cities such as: Uruk, Umma, Zabala, Isin, Eresh, and Nippur).[14][15] There is some scant evidence to suggest that like the later Ur III kings, the rulers of Kish sought to ingratiate themselves to the authorities in Nippur, possibly to legitimize a claim for leadership over the land of Sumer (or at least part of it). The use of the royal title King of Kish expressing a claim of national rulership owes its prestige to the fact that Kish once did rule the entire nation.[16] The city of Kish may have had anywhere from 25,000—40,000 citizens.[12] The empire of Kish may have stretched across anywhere from 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) up to 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi) out of a total of 65,000 km2 (25,000 sq mi) occupied by the Sumerian people c. 2800 – c. 2500 BCE.[13][17]

The SKL states that Kish was the first city to have kings following the flood (beginning with Jushur); moreover, it indicated the existence of a Semitic population in the regions of the Diyala river and northern Mesopotamia. Jushur's successor is referred to as Kullassina-bel; additionally, this is an East Semitic sentence meaning all of them were lord.[18] Thus, some scholars have suggested that this may have been intended to signify the absence of a central authority in Kish for a time. The names of the next ten kings of Kish are: Nangishlishma, En-tarah-ana, Babum, Puannum, Kalibum, Kalumum, Zuqaqip, Atab, Mashda, and Arwium. Most of these names are East Semitic words for animals (e.g. Zuqaqip means scorpion); in fact, most of the names of the first dynasty of Kish may have been Kishite names.[19][20][21][22]

The flood may have devastated Mesopotamia after the first twelve rulers of Kish. The goddess Inanna then handed over the kingship to Etana and the hegemony is said to have resumed at Kish. Etana may be the earliest dynastic name on the SKL known from other legendary sources, whom it called, "the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries". This epithet implies that the historical Etana stabilized the kingdom by bringing peace and order to the area after the flood. He was estimated to have r. c. 2800 – c. 2700 BCE.[23][24][25][26]

The earliest ruler on the SKL whose historical existence has been independently attested through archaeological inscription is Enmebaragesi (r. c. 2750 – c. 2700, c. 2615 – c. 2585 BCE).[23][27][28][29][30][31][32][26][33][34][35] He succeeded Iltasadum on the throne, led a successful campaign against Elam, and captured the ruler of Uruk (Dumuzid).

According to the SKL: Kish held the hegemony over Sumer (where Aga succeeded his father Enmebaragesi and reigned for 625 years). Aga (r. c. 2700 – c. 2670, c. 2585 – c. 2500 BCE) was the 23rd and possibly final king of the first dynasty of Kish.[23][31][26][36] During his reign, he probably took over Umma and Zabala (both of which were dependent of Kish during the ED I); this can be supported by his appearance on the Gem of King Aga (where he is mentioned as the king of Umma). The name of Aga is Sumerian and a rarely attested personal name from the ED, making his identification in royal texts spottable. His name appeared in the Stele of Ushumgal, as the Great Assembly official (gal-ukkin). Aga was also attested in one other composition of historiographical nature: the Tummal Inscription.

-

An illustration of a vase fragment made out of alabaster with a transcription of Mebaragesi as king of Kish. The original is currently in the Iraq National Museum.

-

The Gem of Aga mentioning Ak (𒀝), an alternative naming for Aga. The gem has four columns of text on its faces, and reads: "For Inanna, Aga King of Umma".

-

The daughter of Ushumgal.

-

Three men (possibly from a local council).

-

Another figure.

-

The name "Akka" appears on the Stele of Ushumgal (as "Ak gal-ukkin"). It has been suggested this could refer to king Aga of Kish himself.

-

Line art, transliteration, and translation of the Stele of Ushumgal.

First dynasty of Uruk

[edit]First dynasty of Uruk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2775 BCE–c. 2510 BCE | |||||||||

| Status | In exile (c. 2620 BCE – c. 2510 BCE) | ||||||||

| Capital | Uruk | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sumerian | ||||||||

| Religion | Sumerian religion | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Urukean or Urukian | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Lugal | |||||||||

• c. 2775 – c. 2750 BCE | Meshkiangasher | ||||||||

• c. 2750 – c. 2730 BCE | Enmerkar | ||||||||

• c. 2730 – c. 2700 BCE | Lugalbanda | ||||||||

• c. 2700 BCE | Dumuzid | ||||||||

• c. 2700 – c. 2650 BCE | Gilgamesh | ||||||||

• c. 2650 – c. 2620 BCE | Ur-Nungal | ||||||||

• c. 2620 – c. 2605 BCE | Udul-kalama | ||||||||

• c. 2605 – c. 2596 BCE | La-ba'shum | ||||||||

• c. 2596 – c. 2588 BCE | En-nun-tarah-ana | ||||||||

• c. 2588 – c. 2552 BCE | Mesh-he | ||||||||

• c. 2552 – c. 2546 BCE | Melem-ana | ||||||||

• c. 2546 – c. 2510 BCE | Lugal-kitun | ||||||||

| Legislature | Ukkin | ||||||||

• Ehursag | Ekur | ||||||||

• É | Eanna | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 2775 BCE | ||||||||

| c. 2700 – c. 2670 BCE | |||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 2510 BCE | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| c. 3700 BCE | 0.55 km2 (0.21 sq mi) | ||||||||

| c. 3400 BCE | 0.7 km2 (0.27 sq mi) | ||||||||

| c. 3100 BCE | 2.3 km2 (0.89 sq mi) | ||||||||

| c. 2800 BCE | 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| c. 2500 BCE | 5.41308 km2 (2.09000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• c. 3700 BCE | 8,000—14,000[12] | ||||||||

• c. 3400 BCE | 20,000[12] | ||||||||

• c. 3100 BCE | 40,000—50,000[12] | ||||||||

• c. 2800 BCE | 80,000—90,000[12] | ||||||||

• c. 2500 BCE | 50,000[12] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of Iraq | ||||||||

In Eanna, Meshkiangasher, the son of Utu, became lord and king; he ruled for 324 years. Meshkiangasher entered the sea and disappeared. Enmerkar, the son of Meshkiangasher, the king of Uruk, who built Uruk, became king; he ruled for 420 years. 745 are the years of the dynasty of Meshkiangasher. Lugalbanda, the shepherd, ruled for 1,200 years. Dumuzid, the fisherman whose city was Kuara, ruled for 100 years. He captured Enmebaragesi single-handed. Gilgamesh, whose father was a phantom, the lord of Kulaba, ruled for 126 years. Ur-Nungal, the son of Gilgamesh, ruled for 30 years. Udul-kalama, the son of Ur-Nungal, ruled for 15 years. La-ba'shum ruled for 9 years. En-nun-tarah-ana ruled for 8 years. Mesh-he, the smith, ruled for 36 years. Melem-ana ruled for 6 years. Lugal-kitun ruled for 36 years. 12 kings; they ruled for 2,310 years. Then Uruk was defeated and the kingship was taken to Ur.

— SKL

Meshkiangasher (r. c. 3175 – c. 3150, c. 2775 – c. 2750 BCE) is listed on the SKL as the first king of Eanna.[23][37][31]

He was followed by his son Enmerkar (r. c. 3150 – c. 3100, c. 2750 – c. 2700 BCE).[23][31][37][38][27][39] The legend Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta relates that Enmerkar constructed Eanna (which also served as Uruk's religious precinct after merging with Kulaba).[40][note 1] Based off of information gathered from the poem, Enmerkar is credited with the invention of writing; thus, his reign may mark the very beginning of recorded history during Uruk V—III.[40][41][42][30][43][note 2]

Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat (the message), the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

— Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

Despite his and his father's proclaimed divine descent, neither Enmerkar nor his father were posthumously deified as their successors Lugalbanda, Dumuzid, and Gilgamesh were. The aforementioned three are also known from fragmentary legends. The most famous ruler of this dynasty is Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh (where he is called Lugalbanda's son).

Uruk may have had anywhere from 40,000—82,500 citizens (with up to 90,000 people living within its environs) making it the largest urban area in the world by the Final Uruk period c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE.[12]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sumerian: 𒀉𒇻𒅆; transliterated: a₂.lu.lim; lit. 'stag'

- ^ Sumerian: 𒈗, romanized: king; transliterated: lu.gal; lit. 'big man'

- ^ alternatively: Dumuzi, Ama-ušumgal-ana, or Tammuz; Sumerian: 𒌉𒍣𒉺𒇻, romanized: Dumuzid sipad; transliterated: dumu.zi.sipa: lit. 'faithful son'; Akkadian: Duʾzu, Dūzu; also, 𒀭𒂼𒃲𒁔𒀭𒈾; Syriac: ܬܡܘܙ; Hebrew: תַּמּוּז, transliterated Hebrew: Tammuz, Tiberian Hebrew: Tammûz; Arabic: تمّوز Tammūz

- ^ Kulaba was originally an independent settlement from the Ubaid period that later became the Anu district when it merged with Eanna district to form the city of Uruk.

- ^ The protohistoric, archaeological levels labeled Uruk V, IV, and III (dated to c. 3500 – c. 3000 BCE; Lafont 2016) are to not be confused with the historic dynasties also labeled Uruk III, IV, and V (dated to c. 2340 – c. 2113 BCE; Lafont 2018).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Huot 2019.

- ^ Roux 1966, p. 129.

- ^ a b Wyatt 2010, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e Hasselbach 2005, p. 3.

- ^ a b Ristvet 2014, p. 217.

- ^ a b Foster & Foster 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Edwards, Gadd & Hammond 1970, p. 100.

- ^ Hansen & Ehrenberg 2002, p. 133.

- ^ George 2008.

- ^ van de Mieroop 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Academia.edu 2021a.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Modelski 1997.

- ^ a b c Taagepera 1978, p. 116.

- ^ Steinkeller 2013.

- ^ Frayne 2009.

- ^ Katz 1993, p. 30.

- ^ Cotterell 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Hallo 1963, pp. 52–57.

- ^ Zadok & Zadok 1988, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Maier 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Katz 1993, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Somervill 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Britannica 2019b.

- ^ Roux 1966, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c Academia.edu 2021b.

- ^ a b Thomas & Potts 2020, p. xiii.

- ^ Roux 1990, pp. 138–155.

- ^ Roux 1966.

- ^ a b Pournelle 2003, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d Lafont 2018.

- ^ Edzard, Frye & Soden 2020.

- ^ Beaulieu 2017, p. 36.

- ^ Lombardo 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Scarre, Fagan & Golden 2021, p. 80.

- ^ Kramer 1963, pp. 46–49.

- ^ a b Academia.edu 2021c.

- ^ Lapinkivi 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 135.

- ^ a b Cohen 1973a.

- ^ Katz 2017, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Civil 2013.

- ^ Yushu 2004, p. 7447—7453.

Bibliography

[edit]- Academia.edu (2021a). "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Sumer". The History Files. Kessler Associates (published 1999–2021). Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Academia.edu (2021b). "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Kish / Kic". The History Files. Kessler Associates (published 1999–2021). Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Academia.edu (2021c). "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Uruk". The History Files. Kessler Associates (published 1999–2021). Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2017-11-20) [2017]. A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75 (eBook) (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell (published 2017–2018). ISBN 9781119459071. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopædia (2019-08-09). "Etana Epic". In Lotha, Gloria (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopædia (2019-12-13). "Sumer". In Higgins, John McLaughlin; Lotha, Gloria; Sinha, Surabhi; Tesch, Noah; Tikkanen, Amy (eds.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Civil i Desveus, Miquel (2013-06-18). "REMARKS ON AD-GI4 (A.K.A. "ARCHAIC WORD LIST C" OR "TRIBUTE")" (PDF). Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 65 (revised ed.). Oriental Institute: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.5615/jcunestud.65.2013.0013. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- Cohen, Sol (1973–2005) [c. 2253–1800 BC]. Zólyomi, Gábor; Robson, Eleanor; Cunningham, Graham; Ebeling, Jarle (eds.). "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta". ETCSL. Translated by Jacobsen, Thorkild Peter Rudolph; Krecher, Joachim. United Kingdom: Oxford (published 1973–1996). Retrieved 2021-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Cohen, Sol (1973–2006). Zólyomi, Gábor; Black, Jeremy Allen; Robson, E.; Cunningham, G.; Ebeling, J. (eds.). "Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana". ETCSL. Translated by Berlin, Adele; Cooper, J.; Krecher, Joachim; Vanstiphout, Herman L. J.; Jacobsen, T.; Pettinato, Giovanni; Katz, D.; Tournay, R.; Shaffer, A.; George, A. United Kingdom: Oxford. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Cotterell, A. (2011-05-16). Asia: A Concise History. Wiley. ISBN 9780470829592. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- Edwards, I.; Gadd, C.; Hammond, N. (1970). "II". Early history of the Middle East. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. I (revised ed.). London; New York: CUP (published 1902–2005). ISBN 9780521070515. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- Edzard, D.; Frye, R.; Soden, W. (2020-12-09). "History of Mesopotamia". In Augustyn, A.; Higgins, J.; Lotha, G.; Luebering, J.; Sampaolo, M.; Singh, S.; Tesch, N.; Tikkanen, A.; Young, G.; Zeidan, A. (eds.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- Frayne, Douglas (Fall 2009). "The Struggle for Hegemony in "Early Dynastic II" Sumer". The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies. 4: 65–66. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- Foster, B.; Foster, K. (2009). Civilizations of Ancient Iraq. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691137223. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- George, Andrew R. (2008-05-02) [1993]. Written at United States. House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Michigan: Eisenbrauns (published 1993–2008). ISBN 9780931464805. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hallo, W. (1963). "Beginning and End of the Sumerian King List in the Nippur Recension". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 17 (2). doi:10.2307/1359064. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hansen, D.; Ehrenberg, E. (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. ISBN 9781575060552. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- Hasselbach, R. (2005). Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447051729. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- Huot, Jean-Louis (2019) [2004]. Une archéologie des peuples du Proche-Orient (in French). France: Éditions Errance (published 2004–2019). ISBN 9782877726467. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Jacobsen, T. (1939a). Sumerian King List (PDF) (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Oriental Institute (published 1939–1973). ISBN 978-0226622736. Archived from the original on 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- Katz, D. (1993). Gilgamesh and Akka (1st ed.). Groningen, the Netherlands: STYX Publications. ISBN 9789072371676.

- Katz, D. (2017) [2016]. Drewnowska, O.; Sandowicz, M. (eds.). Ups and Downs in the Career of Enmerkar, King of Uruk. Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Warsaw. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- Kramer, S. (1963) [1963]. The Sumerians: their history, culture, and character. University of Chicago Press (published 1963–2021). ISBN 9780226452388. LCCN 63011398. Archived from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Lafont, B. (2018-11-11) [2008]. Dahl, J.; Englund, B.; Firth, R.; Gombert, B. (eds.). "Rulers of Mesopotamia". cdliwiki: Educational pages of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (published 2008–2018). Retrieved 2021-06-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Lafont, B. (2016-04-18) [2014]. Dahl, J. (ed.). "Chronological periodisation in CDLI". cdliwiki: Educational pages of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (published 2014–2016). Retrieved 2021-06-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Lapinkivi, P. (2008-09-22) [2004]. The Sumerian Sacred Marriage in the Light of Comparative Evidence. Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. ISBN 9789514590580. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- Lombardo, Stanley F. (2019-02-19). Beckman, Gary Michael (ed.). Gilgamesh. Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated. ISBN 9781624667749. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- Maier, J. (2008-05-01). Gilgamesh: A Reader. University of Michigan: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 9780865163393.

- Mittermayer, Catherine (2008-08-21) [2005]. Die Entwicklung der Tierkopfzeichen: eine Studie zur syro-mesopotamischen Keilschriftpaläographie des 3. und frühen 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr (in German). Germany: Ugarit-Verlag (published 2005–2008). ISBN 9783934628595.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Modelski, G. (1997-07-10). "CITIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD: AN INVENTORY (-3500 TO -1200)". Department of Political Science. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2008-07-17. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2008-07-05 suggested (help) - Pournelle, Jennifer R. (2003). Marshland of Cities: Deltaic Landscapes and the Evolution of Early Mesopotamian Civilization. San Diego, California: University of California. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- Pryke, L. (2017-07-14). Ishtar. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781317506645.

- Ristvet, L. (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. ISBN 9781107065215.

- Roux, Georges Raymond Nicolas Albert (1966). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books (published 1966–1992). ISBN 9780140125238. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- Roux, Georges Raymond Nicolas Albert (1990-10-18). La Mésopotamie. Essai d'histoire politique, économique et culturelle (in French). Éditions du Seuil (published 1990–2015). ISBN 9782021291636. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- Scarre, Christopher John; Fagan, Brian Murray; Golden, Charles (2021-04-07) [1997]. Ancient Civilizations (eBook) (5th ed.). Longman (published 1997–2021). ISBN 9780429684388. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Somervill, Barbara A. (2009). Schramer, Leslie (ed.). Empires of Ancient Mesopotamia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781604131574. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- Steinkeller, Piotr (2013). "AN ARCHAIC "PRISONER PLAQUE" FROM KIŠ". Revue D'Assyriologie Et D'archéologie Orientale. 107. Presses Universitaires de France: 131–157. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR i40104838. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- Taagepera, R. (1978). "Size and Duration of Empires: Systematics of Size" (PDF). Social Science Research. 7 (2). University of California, Irvine: Academic Press: 116–117. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(78)90007-8. ISSN 0049-089X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- Thomas, A.; Potts, T. (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications - (Yale) Series. Getty Research Institute. ISBN 9781606066492. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- van de Mieroop, Marc (2003-06-09). A History of the Ancient Near East. Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Vol. 1. Wiley-Blackwell (published 2003–2004). ISBN 9780631225515. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- Wyatt, L. (2010-01-16). Approaching Chaos: Could an Ancient Archetype Save C21st Civilization?. ISBN 9781846942556.

- Yushu, G. (2004). The Sumerian Account of the Invention of Writing —A New Interpretation. Elsevier Ltd.

- Zadok, R.; Zadok, A. (1988). The Pre-Hellenistic Israelite Anthroponymy and Prosopography. Uitgeverij Peeters.