User:Senior citizen smith/Ancient Olympic Games 2

Lede

[edit]Origins

[edit]"The legends of Zeus, Pelops, Heracles, and others are contradictory, and even the ancients found them confusing."

What is more, the Olympian Games are an invention of theirs [the Elieans]; and it was they who celebrated the first Olympiads, for one should disregard the ancient stories both of the founding of the temple and of the establishment of the games—some alleging that it was Heracles, one of the Idaean Dactyli,134 who was the originator of both, and others, that it was Heracles the son of Alcmene and Zeus, who also was the first to contend in the games and win the victory; for such stories are told in many ways, and not much faith is to be put in them. It is nearer the truth to say that from the first Olympiad, in which the Eleian Coroebus won the stadium-race, until the twenty.sixth Olympiad, the Eleians had charge both of the temple and of the games. But in the times of the Trojan War, either there were no games in which the prize was a crown or else they were not famous, neither the Olympian nor any other of those that are now famous.

Morgan, Catherine (1990). Athletes and Oracles: The Transformation of Olympia and Delphi in the Eighth Century BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37451-4.

It remains for me to tell about Olympia, and how everything fell into the hands of the Eleians. The temple is in Pisatis, less than three hundred stadia distant from Elis. In front of the temple is situated a grove of wild olive trees, and the stadium is in this grove. Past the temple flows the Alpheius, which, rising in Arcadia, flows between the west and the south into the Triphylian Sea. At the outset the temple got fame on account of the oracle of the Olympian Zeus; and yet, after the oracle failed to respond, the glory of the temple persisted none the less, and it received all that increase of fame of which we know, on account both of the festal assembly and of the Olympian Games, in which the prize was a crown and which were regarded as sacred, the greatest games in the world.

- Strabo, Geography 8.3 (ed. H. L. Jones, 1924)

History

[edit]Events

[edit]| Events at the Olympics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Olympiad | Year | Event |

| 1st | 776 BC | Stade |

| 14th | 724 BC | Diaulos |

| 15th | 720 BC | Long distance race (Dolichos) |

| 18th | 708 BC | Pentathlon, Wrestling |

| 23rd | 688 BC | Boxing (pygmachia) |

| 25th | 680 BC | Four horse chariot race (tethrippon) |

| 33rd | 648 BC | Horse race (keles), Pankration |

| 37th | 632 BC | Boys stade and wrestling |

| 38th | 628 BC | Boys pentathlon |

| 41st | 616 BC | Boys boxing |

| 65th | 520 BC | Hoplite race (hoplitodromos) |

| 70th | 500 BC | Mule-cart race (apene) |

| 93rd | 408 BC | Two horse chariot race (synoris) |

| 96th | 396 BC | Competition fo heralds and trumpeters |

| 99th | 384 BC | Tethrippon for horse over one year |

| 128th | 266 BC | Chariot for horse over one year |

| 131st | 256 BC | Race for horses older than one year |

| 145th | 200 BC | Pankration for boys |

The program gradually increased to twenty-three contests, although no more than twenty featured at any one Olympiad.[1]

Youth events are recorded as starting in 632 BC. paides

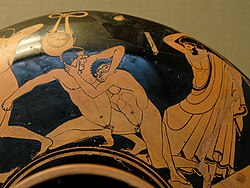

Our knowledge of how the events were performed primarily derives from the paintings of athletes found on many on vases, particularly those of the Archaic and Classical periods.[2]

Running

[edit]

332-333 BC, British Museum.

The only event recorded at the first thirteen games was the stade, a straight-line sprint of just over 192 metres.[3] The diaulos (lit. "double pipe"), or two-stade race, is recorded as being introduced at the 14th Olympiad in 724 BC. It is thought that competitors ran in lanes marked out with lime or gypsum for the length of a stade then turned around separate posts (kampteres), before returning to the start line.[4] Xenophanes wrote that "Victory by speed of foot is honored above all."

A third foot race, the dolichos ("long race"), was introduced in the next Olympiad. Accounts of the race's distance differ, it seems to have been from twenty to twenty-four laps of the track, around 7.5 km to 9 km, although it may have been lengths rather laps and thus half as far.[5][6]

The last running event added to the Olympic program was the hoplitodromos, or "Hoplite race", introduced in 520 BC and traditionally run as the last race of the games. Competitors ran either a single or double diaulos (approximately 400 or 800 metres) in full military armour.[7]

Combat

[edit]

Detail from an Attic red-figure kylix c.490-480 BC, British Museum

Wrestling (pale) is recorded as being introduced at the 18th Olympiad. Three throws were necessary for win. A throw was counted if the body, hip, back or shoulder (and possibly knee) touched the ground. If both competitors fell nothing was counted. Unlike its modern counterpart Greco-Roman wrestling, it is likely that tripping was allowed.[8]

Boxing (pygmachia) was first listed in 688 BC,[9] the boys event sixty years later. The laws of boxing were ascribed to the first Olympic champion Onomastus of Smyrna.[10] It appears body-blows were either not permitted or not practised.[11][12] The Spartans, who claimed to have invented boxing, quickly abandoned it and did not take part in boxing competitions.[13] At first the boxers wore himantes (sing. himas), long leather strips which were wrapped around their hands.[14]

The pankration was introduced in the 33rd Olympiad (648 BC).[15] Boys' pankration became an Olympic event in 200 BC, in the 145th Olympiad.[16] As well as techniques from boxing and wrestling, athletes used kicks,[17] locks, and chokes on the ground. Although the only prohibitions were against biting and gouging, the pankration was regarded as less dangerous than boxing.[18]

One of the most popular events, Pindar wrote eight odes praising victors of the pankration.[19] A famous event in the sport was the posthumous victory of Arrhichion of Phigaleia who "expired at the very moment when his opponent acknowledged himself beaten."Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

Pentathlon

[edit]The pentathlon was a combined competetion in five events: running, long jump, diskos throw, javelin throw and wrestling.[20] The pentathlon is said to have first appeared at 18th Olympiad in 708 BC.[21] The competition was held on single day,[22] but it is not known how the victor was decided,[23][24] or in what order the events occured,[25] except that it finished with the wrestling.[26]

Equestrian

[edit]Athletes

[edit]Culture

[edit]Site

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of ancient olympic victors

- Pindar

- Heraea Games

- Olympic Games

- Nemean Games

- Isthmian Games

- Panathenaic Games

- Olympic Games ceremony

- Archaeological Museum of Olympia

- Ludi, the Roman games influenced by Greek traditions

Notes

[edit]- ^ Crowther ??

- ^ Young, p. 18

- ^ Miller, p. 33

- ^ Miller, p. 44

- ^ Golden, p. 55. "The dolichos varied in length from seven to twenty-four lengths of the stadium - from 1,400 to 4,800 Greek feet."

- ^ Miller, p. 32 "The sources are not unanimous about the length of this race: some claim that it was twenty laps of the stadium track, others that it was twenty-four. It may have differed from site to site, but it was in the range of 7.5 to 9 kilometers."

- ^ Miller, p. 33

- ^ Gardiner, p. 374-

- ^ Miller, p. 51

- ^ Gardiner, p. 402

- ^ Gardiner, p. 421

- ^ To judge from the story of Damoxenos and Kreugas who boxed at the Nemean Games, after a long battle with no result combatants could agree to a free exchage of hits. (Gardiner, p. 432)

- ^ Gardiner, p. 402

- ^ Miller, p. 51

- ^ Gardiner, p. 435

- ^ Miller, p. 60

- ^ Gardiner, p. 445-6 "Galen, in his skit on the Olympic games, awards the prize [in the pakration] to the donkey, as the best of all animals in kicking."

- ^ Finley & Pleket, p. 41

- ^ Gardiner, p. 437

- ^ Gariner, p. 359

- ^ Miller, p. 60

- ^ Young, p. 32

- ^ Young, p. 19

- ^ Gardiner, p. 362-3

- ^ Gardiner, p. 362-5

- ^ Gardiner, p. 363

Sources

[edit]- "Olympics Through Time" Foundation of the Hellenic World

- Young, David C. (2004). A Brief History of the Olympic Games (PDF). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-405-11130-5.

- Schaus, Gerald P., R. Wenn, Stephen, ed. (2009). Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-779-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Faulkner, Neil (2012). A Visitor's Guide to the Ancient Olympics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16029-1.

- Finley, M. I.; H. W., Pleket (2012). The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-14941-7.

- Swaddling, Judith (1999). The Ancient Olympic Games. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77751-4.

- Perrottet, Tony (2004). The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-382-4.

- Miller, Stephen G. (2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11529-6.

- Golden, Mark (1998). Sport and Society in Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49790-9.

- Kyle, Donald G. (2014). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-61356-6.

- Newby, Zahra (2005). Greek Athletics in the Roman World: Victory and Virtue. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-927930-2.

- Gardiner, E. N. (1910). Greek athletic sports and festivals. London : Macmillan.

- Christesen, Paul. "The Transformation of Athletics in Sixth Century Greece".

- Lee, Hugh M. (6 April 2004). "Stadia and Stating Gates". Archaeology.

- Nelson, Max. "The First Olympic Games".

- König, Jason (21 July 2012). "The opening ceremony at the ancient Olympics". Ancient and Modern Olympics.

- Kyle, Donald G. (6 April 2004). "Winning at Olympia". Archaeology.

further reading

- Dillon, Matthew. "Did Parthenoi Attend the Olympic Games? Girls and Women Competing, Spectating, and Carrying out Cult Roles at Greek Religious Festivals" Hermes 128.4 (Jan 1, 2000): 457. (one page)

- Farrington, Andrew. "Olympic victors and the popularity of the Olympic games in the Imperial period", Tyche 12 (1997), 15-46.

- Hornblower, Simon. "Thucydides, Xenophon, and Lichas: Were the Spartans Excluded from the Olympic Games from 420 to 400 B. C.?" Phoenix 54, no. 3/4 (2000): 212-25

- Harris, J. P. "Revenge of the Nerds: Xenophanes, Euripides, and Socrates vs. Olympic Victors." American Journal of Philology 130.2 (2009): 157-194.

Ancient

[edit]- Pausanias, Description of Greece. (Trans. W. H. S. Jones)

- Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War 431 BC (Trans. R. Crawley)

- Plato, Apology

- Plato, Laws

- Xenophanes, Fragment 2

- Pindar, Olympian

- Plutarch, Aristotle

- Plutarch, Lycurgus

- Plutarch, Thermistocles

- Strabo, Geography (8.3.30)

- Philostratus Gymnasticus

- Epictetus, Discourses of Epictetus

- Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers

- Xenophon, Hellenica

- Lysias, Olympic Oration

- Julius Africanus, Chronographiae

- Eusebius, Chronicle

- Aristotle, Rhetoric

- Pliny, Natural History

- Herodotus, Histories (8.26.3)

- Aristophanes, Lysistrata

- Diodorus Siculus, Library (17.109.1-2)

External links

[edit]- The Ancient Olympic Games virtual museum (requires registration)

- Ancient Olympics: General and detailed information

- The story of the Ancient Olympic Games

- The origin of the Olympics

- Olympia and Macedonia: Games, Gymnasia and Politics. Thomas F. Scanlon, professor of Classics, University of California

- Webquest The ancient and modern Olympic Games[dead link]

- Goddess Nike and the Olympic Games: Excellence, Glory and Strife

Olympic Games Category:Festivals in ancient Greece Category:History of Gymnastics Category:History of the Olympics Olympic Games Category:Multi-sport events Category:Olympic Games Category:Panhellenic Games Category:Recurring sporting events established before 1750 Category:8th-century BC establishments in Greece Category:Greek inventions