User:Renzoy16/sandbox1

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

| Supreme Court of the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| Kataas-taasang Hukuman ng Pilipinas Korte Suprema ng Pilipinas | |

| |

| |

| 14°34′47″N 120°59′04″E / 14.5798°N 120.9844°E | |

| Established | June 11, 1901 |

| Location | Padre Faura Street, Ermita, Manila, Metro Manila |

| Coordinates | 14°34′47″N 120°59′04″E / 14.5798°N 120.9844°E |

| Motto | Batas at Bayan (Law and Nation) |

| Composition method | Presidential appointment from the shortlisted candidates submitted by the Judicial and Bar Council |

| Authorised by | Art. VIII, 1987 Constitution of the Philippines |

| Judge term length | No fixed term; mandatory retirement upon reaching the age of 70 |

| Number of positions | 15 |

| Annual budget | P 30.687 billion (2018)[1] |

| Website | sc.judiciary.gov.ph |

| Chief Justice | |

| Currently | Lucas Bersamin |

| Since | November 28, 2018 |

|

|---|

|

|

The Supreme Court of the Philippines, also referred to as the Kataas-taasang Hukuman ng Pilipinas in Filipino or referred to as simply by its colloquial term Korte Suprema, is the highest court in the Philippines. The Court was established by the second Philippine Commission in June 11, 1901 through the enactment of Act No. 136, an Act which had abolished the Real Audiencia de Manila.[2][3][4]

The Supreme Court Complex, which was formerly the part of the University of the Philippines Manila campus,[5] occupies the corner of Padre Faura Street and Taft Avenue in Manila, with the main building directly fronting the Philippine General Hospital. Until 1945, the Court met in Cavite.

Location

[edit]To include information about the summer residence in Baguio using the following references:

- https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/200482-reasons-supreme-court-justices-baguio-every-april

- https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/67082

- https://arellanolaw.edu/alpr/v4n1a.pdf

History

[edit]Pre-hispanic period

[edit]Prior to the conquest of Spain, the islands of the Philippines were composed of independent barangays, each of which is community composed of 30 to 100 families. Typically, a barangay is headed by a datu or a local chief who exercises all functions of government—executive, legislative and judicial; he is also the commander-in-chief in times of war. Each barangay has its own laws. Laws may be oral laws, which are the traditions and customs of the locality handed down from a generation to generation, or written laws as promulgated by the datu who is typically aided by a group of elders. In a confederation of barangays, the laws are promulgated by a superior datu with the aid of the inferior datus.[6]

In a resolution of dispute, the datu acts as a judge while a group of elders sits as a jury. If a dispute is between datus or between members of different barangays, the dispute is settled through arbitration with some other datus or elders, serving as arbiters or mediators, from other barangays. All trials are held public. When a datu is in doubt if who between the parties are guilty, the trial is resorted to trial by ordeal—a common practice in criminal cases. An accused who was innocent was always perceived to be always successful in such ordeals, because the deities or gods of these pre-hispanic people made the said accused do so.[6]

Hispanic period

[edit]In the royal order of August 14, 1569, Miguel López de Legazpi was confirmed as the Governor and Captain-General of the Philippines. He was empowered to administer civil and criminal justice in the islands. Under the same order, Legazpi had original and appellate jurisdiction in all suits and constituted in his person all authority of a department of justice, with complete administrative and governmental control of all judicial offices. In subsequent cédulas and royal orders, it was made the duty of all officials to enforce all laws and ordinances issued for the benefits of the locals, but these were not made to have been done. In a 1583 letter written by Bishop Domingo de Salazar to King Philip II, Bishop Salazar noted the different acts of oppression and injustice committed against the native Filipinos and that the decrees of the King, which were designed to protect them, were generally disregarded by the Governor-General and his subordinates.[7]

As a result of these developments, the first real audiencia (which is the Real Audiencia of Manila) or high court was established in the Philippines through the royal decree of May 5, 1583. The decree stated that "the court is founded in the interests of good government and the administration of justice, with the same authority and preeminence as each of the royal audiencias in the town of Valladolid and the city of Granada.[7] The audiencia was composed of a president, three oidores or auditors, a fiscal or prosecuting attorney, and the necessary auxiliary officials, such as the court's secretaries and clerks.[6][7] The first president was Governor-Captain General Santiago de Vera.[7]

The Real Audiencia of Manila had a jurisdiction covering Luzon and the rest of the archipelago. It was given an appellate jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases decided by the governors, alcaldes mayores and other magistrates of the islands. The audiencia may only take cognizance of a civil case in its first instance when, on account of its importance, the amount involved and the dignity of the parties might be tried in a superior court; and of criminal cases which may arise in the place where the audiencia might meet. The decisions of the audiencia in both civil and criminal cases were to be executed without any appeal, except in civil cases were the amount was so large as to justify an appeal to the King; such appeal to the King must be made within one year. All cases were to be decided by a majority vote, and in case of a tie, an advocate was chosen for the determination of the case.[7]

The audiencia would later on be dissolved through the royal cédula of August 9, 1589. The audiencia would later on be reestablished through the royal decree of May 25, 1596, and on May 8, 1598, it had resumed its functions as a high court. By its reestablishment, the audiencia was composed of a president as represented by the governor, four associate justices, prosecuting attorney with the office of protector of the Indians, the assistant prosecuting officers, a reporter, clerk and other officials.[7] By a royal order of March 11, 1776, the audiencia was reorganized; it consisted of the president, a regent, the immediate head of the audiencia, five oidores or associate justices, two assistant prosecuting attorneys, five subordinate officials, and two reporters. It had also been allowed to perform the duties of a probate court in special cases. When the high court is acting as administrative or advisory body, the audiencia acted under the name of real acuerdo. Later on the governor-general was removed as the president of the audiencia and the real acuerdo was abolished by virtue of the royal decree of July 4, 1861.[7] The same royal decree converted the court to a pure judicial body, with its decisions appealable to the Supreme Court of Spain.[8] By the royal decree of October 24, 1870, the audiencia was branched into two chambers; these two branches were later renamed as sala de lo civil and sala de lo criminal by virtue of royal decree of May 23, 1879.[7]

On February 26, 1886, the territorial audiencia of Cebu was established through a royal decree, and covers the jurisdiction of the islands of Cebu, Negros, Panay, Samar, Paragua, Calamianes, Masbate,Ticao, Leyte, Jolo and Balabac, including the smaller and adjacent islands of aformentioned islands. By January 5, 1891, a royal decree had established the territorial audiencias of Manila and Cebu. By virtue of a royal decree, the territorial audiencia in Cebu continued until May 19, 1893 were it ceased to be territorial; its audiencia for criminal cases, however, was retained.[7] From the same royal decree, the audiencia in Vigan was established and covers criminal cases in Luzon and Batanes. These courts decisions are not considered final as they are still appealable to the Audiencia Territorial of Manila and those of the audiencia to the Supreme Court of Spain.[6] These audiencias would still continue to operate even until the outbreak of the Filipino rebellion in 1896.[7]

American period

[edit]From the start of the American occupation on August 13, 1898, the audiencias of Cebu and Vigan ceased to function as the judges fled for safety. The following day, Wesley Merritt, the first American Military Governor, ordered the suspension of the territorial jurisdiction of the the colonial Real Audiencia of Manila, and of other minor courts in the Philippines. All trial of committed crimes and offenses were transferred to the jurisdiction of the court-martial or military commissions of the United States. On October 7, 1898, the civil courts throughout the islands that were constituted under Spanish laws prior to August 13 were permitted to resume their civil jurisdiction but subject to supervision of the American military government. Later on in January 1899, the civil jurisdiction of the audiencia in Manila was suspended but was restored in May 1899 after it was reestablished as the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands. The criminal jurisdiction was also restored to the newly reformed civil high court.[7]

On June 11, 1901, the current Supreme Court was officially established through enactment of Act No. 136, otherwise known as the Judiciary Law of the Second Philippine Commission.[9] The said law reorganized the judicial system and vested the judicial power to the Supreme Court, Courts of First Instance and Justice of the Peace courts. The said law also provided for the early composition of the said High Court, having one Chief Justice and six Associate Justices—all appointed by the Commission.[6][7] The Philippine Organic Act of 1902 and the Jones Act of 1916, both passed by the U.S. Congress, ratified the jurisdiction of the Courts vested by Act No. 136. The Philippine Organic Act of 1902 further provides that the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and its six Associate Justices shall be appointed by the President of the United States with the consent and advice of the U.S. Senate.[6]

The enactment of the Administrative Code of 1917 made the Supreme Court the highest tribunal. It also increased the total membership of the Supreme Court, having one Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices.[10]

Commonwealth period

[edit]With the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines through the ratification of the 1935 Constitution, the Supreme Court's composition was increased to eleven, with one Chief Justice and ten Associate Justices.[n] The 135 Constitution provided for the independence of the judiciary, the security of tenure of its members, prohibition on diminution of compensation during their term of office, and the method of removal of the justices through impeachment. The Constitution also transferred the rule-making of the legislature to the Supreme Court on the power to promulgate rules concerning pleading, practice, court procedures, and admission to the practice of law.[6]

Japanese occupation

[edit]

Within the brief Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the Court remained with no substantial changes in its organizational structure and jurisdiction. However, some acts and outlines of the Court were required to be approved first by the Military Governor of the Imperial Japanese Force.[6] In 1942, José Abad Santos—the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court—was executed by Japanese troops after refusing to collaborate with the Japanese military government. He was captured on April 11, 1942 in the province of Cebu and was executed on May 7, 1942 in the town of Parang in Mindanao.[11]

Independence and postwar period

[edit]After the end of the Japanese occupation during World War II, Philippines was granted its independence on July 4, 1946 from the United States. The grant of independence was made through the Treaty of Manila of 1946. In the said treaty, it provides that:

ARTICLE V. – The Republic of the Philippines and the United States of America agree that all cases at law concerning the Government and people of the Philippines which, in accordance with section 7 (6) of the Independence Act of 1934, are pending before the Supreme Court of the United States of America at the date of the granting of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines shall continue to be subject to the review of the Supreme Court of the United States of America for such period of time after independence as may be necessary to effectuate the disposition of the cases at hand. The contracting parties also agree that following the disposition of such cases the Supreme Court of the United States of America will cease to have the right of review of cases originating in the Philippine Islands.[o]

In effect of the treaty, the United States Supreme Court ceased to have appellate power to review cases originating from the Philippines after its independence, with exception of those cases pending before the United States Supreme Court filed prior to the country's independence.

In June 17, 1948, the Judiciary Act of 1948 was enacted. The law grouped cases together over which the high court could exercise its exclusive jurisdiction to review on appeal, certiorari, or writ of error.[3]

In 1973, the 1935 Constitution was revised and was replaced by the 1973 Constitution. Under the said Constitution, the membership of the court was increased to its current number, which is fifteen.[p] All members are said to be appointed by the President alone, without consent, approval, or recommendation of a body or officials.[q] The 1973 Constitution also vested in the Supreme Court administrative supervision over all lower courts which heretofore was under the Department of Justice.

The martial law period brought in many legal issues of transcendental importance and consequence: some of which were the legality of the ratification of the 1973 Constitution, the assumption of the totality of government authority by President Marcos, the power to review the factual basis for a declaration of Martial Law by the Chief Executive.[3]

Post–EDSA revolution and present

[edit]After the overthrow of President Ferdinand Marcos in 1986, President Corazon Aquino, using her emergency powers, promulgated a transitory charter known as the "Freedom Constitution" which did not affect the composition and powers of the Supreme Court. The Freedom Charter was replaced by the 1987 Constitution which is the fundamental charter in force in the Philippines at present. Under the current Constitution, it retained and carried the provision in the 1935 and 173 Constitutions that "judicial power is vested in one Supreme Court and in such lower courts as may be established by law." However, unlike the previous Constitutions, the current Constitution expanded the Supreme Court's judicial power by defining it in the second paragraph of Section 1, Article VIII as:

SECTION 1. — xxx Judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government.[r]

The definition, in effect, diluted the of the political question doctrine, that is it is best to submit specific questions or issues specific questions to the political wisdom of the people, and thus, as a result, are beyond the review of the courts.[3]

Furthermore, the present Constitution provided for safeguards to ensure the independence of the Judiciary. It also provided for the Judicial and Bar Council, a constitutionally-created body that that recommends appointees for vacancies that may arise in the composition of the Supreme Court and other lower courts.[3]

Overview

[edit]Qualifications

[edit]According to the Constitution, for a person to be appointed to the Supreme Court, he must be:

- a natural-born citizen of the Philippines;

- at least forty years of age, and

- have been for fifteen years or more a judge of a lower court or engaged in the practice of law in the Philippines.[d]

An additional constitutional requirement, though less precise in nature, is that a judge "must be a person of proven competence, integrity, probity, and independence."[e]

Composition and manner of appointment

[edit]Pursuant to Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines, the Court is composed of the Chief Justice and of the fourteen Associate Justices,[a] all of whom are appointed by the President from a list of nominees made by the Judicial and Bar Council.[b] An appointment to the Supreme Court needs no confirmation of the Commission on Appointments as the nomination is already vetted by the Judicial and Bar Council, a constitutionally-created body which recommends appointments within the judiciary.[b][c]

Upon a vacancy in the Court, whether for the position of Chief Justice or Associate Justice, the President fills the vacancy by appointing a person from a list of at least 3 nominees prepared by the Judicial and Bar Council.[b]

Retirement

[edit]The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines provides that:

"SECTION 11. The Members of the Supreme Court xxx shall hold office during good behavior until they reached the age of seventy years or become incapacitated to discharge the duties of their office."[g]

Supreme Court Justices are obliged to retire upon reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70.[f] Some Justices have opted to retire before reaching the age of 70, such as Florentino Feliciano, who retired at 67 to accept appointment to the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization and Alicia Austria-Martinez who retired at 68 due to health reasons.[12][13]

Since 1901, only Associate Justice Austria-Martinez had resigned for health reasons. In September, 2008, Austria-Martinez, citing health reasons, filed a letter to the Court through Chief Justice Reynato Puno, tendering her resignation effective April 30, 2009, or 15 months before her compulsory retirement on December 19, 2010.[14] This was followed by Justice Martin Villarama Jr., who resigned in January 2016 due to health reasons.[15]

Language

[edit]Since the courts' creation, English had been used in court proceedings. But for the first time in Philippine judicial history, or on August 22, 2007, three Malolos City regional trial courts in Bulacan will use Filipino, to promote the national language. Twelve stenographers from Branches 6, 80 and 81, as model courts, had undergone training at Marcelo H. del Pilar College of Law of Bulacan State University College of Law following a directive from the Supreme Court of the Philippines. De la Rama said it was the dream of Chief Justice Reynato Puno to implement the program in other areas such as Laguna, Cavite, Quezon, Nueva Ecija, Batangas, Rizal, and Metro Manila.[16]

Powers and jurisdiction

[edit]

Adjudicatory powers

[edit]The powers of the Supreme Court are defined in Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution. These functions may be generally divided into two—judicial functions and administrative functions. The administrative functions of the Court pertain to the supervision and control over the Philippine judiciary and its employees, as well as over members of the Philippine bar. Pursuant to these functions, the Court is empowered to order a change of venue of trial in order to avoid a miscarriage of justice and to appoint all officials and employees of the judiciary.[h] The Court is further authorized to promulgate the rules for admission to the practice of law, for legal assistance to the underprivileged, and the procedural rules to be observed in all courts.[h]

The more prominent role of the Court is located in the exercise of its judicial functions. Section 1 of Article VIII contains definition of judicial power that had not been found in previous constitutions. The judicial power is vested in “one Supreme Court and in such lower courts as may be established by law."[i] This judicial power is exercised through the judiciary's primary role of adjudication, which includes the "duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the government."[i]

The definition reaffirms the power of the Supreme Court to engage in judicial review, a power that had traditionally belonged to the Court even before this provision was enacted. Still, this new provision effectively dissuades from the easy resort to the political question doctrine as a means of declining to review a law or state action, as was often done by the Court during the rule of President Ferdinand Marcos.[17] As a result, the existence of "grave abuse of discretion" on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the government is sufficient basis to nullify state action.

Original jurisdiction

[edit]

The other mode by which a case reaches the Supreme Court is through an original petition filed directly with the Supreme Court, in cases that the Constitution establishes "original jurisdiction" with the Supreme Court. Under Section 5(1), Article VIII of the Constitution, they are "cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and over petitions for certiorari, prohibition, mandamus, quo warranto, and habeas corpus." Resort to certiorari, prohibition and mandamus may be availed of only if "there is no appeal, or any plain, speedy, and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law."[j]

However, notwithstanding the grant of original jurisdiction, the Court has, through the years, assigned to lower courts such as the Court of Appeals the power to hear petitions for certiorari, prohibition, mandamus, quo warranto and habeas corpus. As a result, the Court has considerable discretion to refuse to hear these petitions filed directly before it on the ground that such should have been filed instead with the Court of Appeals or the appropriate lower court. Nonetheless, cases that have attracted wide public interest or for which a speedy resolution is of the essence have been accepted for decision by the Supreme Court without hesitation.

In cases involving the original jurisdiction of the Court, there must be a finding of "grave abuse of discretion" on the part of the respondents to the suit to justify favorable action on the petition. The standard of "grave abuse of discretion", a markedly higher standard than "error of law", has been defined as "a capricious and whimsical exercise of judgment amounting to lack of jurisdiction."[k]

Appellate review

[edit]Far and away the most common mode by which a case reaches the Supreme Court is through an appeal from a decision rendered by a lower court. Appealed cases generally originate from lawsuits or criminal indictments filed and tried before the trial courts. These decisions of the trial courts may then be elevated on appeal to the Court of Appeals, or more rarely, directly to the Supreme Court if only “questions of law” are involved. Apart from decisions of the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court may also directly review on appeal decisions rendered by the Sandiganbayan and the Court of Tax Appeals. Decisions rendered by administrative agencies are not directly appealable to the Supreme Court, they must be first challenged before the Court of Appeals. However, decisions of the Commission on Elections may be elevated directly for review to the Supreme Court, although the procedure is not, strictly speaking, in the nature of an appeal.

Review on appeal is not as a matter of right, but "of sound judicial discretion and will be granted only when there are special and important reasons therefor".[l] In the exercise of appellate review, the Supreme Court may reverse the decision of lower courts upon a finding of an "error of law". The Court generally declines to engage in review the findings of fact made by the lower courts, although there are notable exceptions to this rule. The Court also refuses to entertain cases originally filed before it that should have been filed first with the trial courts.

Rule-making power

[edit]The Supreme Court has the exclusive power to promulgate rules concerning the protection and enforcement of constitutional rights, pleading, practice, and procedure in all courts, the admission to the practice of law, the integrated bar, and legal assistance to the underprivileged. Any such rules shall provide a simplified and inexpensive procedure for the speedy disposition of cases, shall be uniform for all courts of the same grade, and shall not diminish, increase, or modify substantive rights. Rules of procedure of special courts and quasi‐judicial bodies shall remain effective unless disapproved by the Supreme Court. (Art. VIII, §54(5))

Writs of amparo and habeas data

[edit]The Supreme Court approved the Writ of Amparo on September 25, 2007.[18] The writ of amparo (Spanish for protection) strips the military of the defense of simple denial. Under the writ, families of victims have the right to access information on their cases—a constitutional right called the "habeas data" common in several Latin American countries. The rule is enforced retroactively. Chief Justice Puno stated that "If you have this right, it would be very, very difficult for State agents, State authorities to be able to escape from their culpability."[19][20]

The Resolution and the Rule on the Writ of Amparo gave legal birth to Puno's brainchild.[21][22][23] No filing or legal fees is required for Amparo which takes effect on October 24. Puno also stated that the court will soon issue rules on the writ of Habeas Data and the implementing guidelines for Habeas Corpus. The petition for the writ of amparo may be filed "on any day and at any time" with the Regional Trial Court, or with the Sandiganbayan, the Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court. The interim reliefs under amparo are: temporary protection order (TPO), inspection order (IO), production order (PO), and witness protection order (WPO, RA 6981).[24]

The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) has criticized the Writ of Amparo and Habeas Data for being insufficient, saying further action must be taken, including enacting laws for protection against torture, enforced disappearance, and laws to provide legal remedies to victims. AHRC said the writ failed to protect non-witnesses, even if they too face threats.[25]

On August 30, 2007, Puno vowed to institute the writ of habeas data as a new legal remedy to the extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. Puno explained that the writ of amparo denies to authorities defense of simple denial, and habeas data can find out what information is held by the officer, rectify or even the destroy erroneous data gathered.[26]

On January 22, 2008, the Supreme Court en banc approved the rules for the writ of Habeas Data ("to protect a person’s right to privacy and allow a person to control any information concerning them"), effective on February 2, the Philippines’ Constitution Day.[27]

Divisions

[edit]The Court is authorized to sit either en banc or in divisions of three, five or seven members. Since the 1987, the Court has constituted itself in 3 divisions with 5 members each. A majority of the cases are heard and decided by the divisions, rather than the court en banc. However, the Constitution requires that the Court hear en banc "[a]ll cases involving the constitutionality of a treaty, international or executive agreement, as well as "those involving the constitutionality, application, or operation of presidential decrees, proclamations, orders, instructions, ordinances, and other regulations".[28] The Court en banc also decides cases originally heard by a division when a majority vote cannot be reached within the division. The Court also has the discretion to hear a case en banc even if no constitutional issue is involved, as it typically does if the decision would reverse precedent or presents novel or important questions.

Formerly under the 1935, 1973 and the 1986 Freedom Constitutions, the Court is authorized only to sit either en banc or in divisions of two.

Membership

[edit]Current Justices

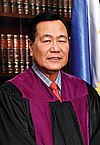

[edit]The Supreme Court consists of a chief justice, currently held by Lucas Bersamin, and fourteen associate justices. Among the current members of the Court, Antonio Carpio is the longest-serving justice, with a tenure of 8,439 days (23 years, 38 days) as of December 3, 2024; the most recent justice to join the court is Amy Lazaro-Javier, whose tenure began on March 6, 2019.

| Justice Birthdate and place |

Position | Appointed by | Tenure Length of service |

Previous position or office (Most recent prior to joining the Court) |

Succeeded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lucas P. Bersamin October 18, 1949 Bangued, Abra |

Chief Justice | Duterte | November 26, 2018–present (6 years, 7 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2002–2009) |

Teresita L. de Castro |

| Associate Justice | Macapagal–Arroyo | April 3, 2009 – November 26, 2018 (9 years, 237 days) |

Adolfo S. Azcuna | |||

|

Antonio T. Carpio October 26, 1949 Davao City |

Senior Associate Justice | Macapagal–Arroyo | October 26, 2001–present (23 years, 38 days) |

Legal counsel of Vice-President Gloria Macapagal–Arroyo (2001) |

Minerva P. Gonzaga-Reyes |

|

Diosdado M. Peralta March 27, 1949 Laoag City, Ilocos Norte |

Associate Justice | Macapagal–Arroyo | January 13, 2009–present (15 years, 325 days) |

Presiding Justice of the Sandiganbayan (2008–2009) |

Ruben T. Reyes |

|

Mariano C. del Castillo July 29, 1949 Dipolog, Zamboanga del Norte |

Macapagal–Arroyo | July 29, 2009–present (15 years, 127 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2001–2009) |

Ma. Alicia Austria–Martinez | |

|

Estela M. Perlas–Bernabe May 14, 1952 Plaridel, Bulacan |

Aquino III | September 16, 2011–present (13 years, 78 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2004–2011) |

Conchita C. Carpio–Morales | |

|

Mario Victor F. Leonen December 29, 1962 Baguio City |

Aquino III | November 12, 2012–present (12 years, 21 days) |

Chief Peace Negotiator of the Republic with the MILF (2010–2012) |

Maria Lourdes A. Sereno | |

|

Francis H. Jardeleza September 26, 1949 Jaro, Iloilo |

Aquino III | August 19, 2014–present (10 years, 106 days) |

Solicitor General (2012–2014) |

Roberto A. Abad | |

|

Alfredo Benjamin S. Caguioa September 26, 1959 |

Aquino III | January 22, 2016–present (8 years, 316 days) |

Acting Secretary of Justice (2015–2016) |

Martin S. Villarama Jr. | |

|

Andres B. Reyes, Jr. May 11, 1950 |

Duterte | July 12, 2017–present (7 years, 144 days) |

Presiding Justice of the Court of Appeals (2010–2017) |

Bienvenido L. Reyes | |

|

Alexander G. Gesmundo November 6, 1956 |

Duterte | August 14, 2017–present (7 years, 111 days) |

Associate Justice of the Sandiganbayan (2005–2017) |

Jose C. Mendoza | |

|

Jose C. Reyes Jr. September 18, 1950 |

Duterte | August 10, 2018–present (6 years, 115 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2003–2018) |

Presbitero J. Velasco Jr. | |

|

Ramon Paul L. Hernando August 27, 1966 |

Duterte | October 10, 2018–present (6 years, 54 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2010–2018) |

Samuel R. Martires | |

|

Rosmari D. Carandang January 9, 1952 |

Duterte | November 26, 2018–present (6 years, 7 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2003–2018) |

Teresita L. de Castro | |

| Amy C. Lazaro–Javier November 16, 1956 |

Duterte | March 6, 2019–present (5 years, 272 days) |

Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals (2007–2019) |

Noel G. Tijam | ||

| Vacant | Duterte | — | — | Lucas P. Bersamin | ||

Court demographics

[edit]

By law school[edit]

By appointing President[edit]

|

By gender[edit]

|

Public perception

[edit]Judicial corruption

[edit]On January 25, 2005, and on December 10, 2006, Philippines Social Weather Stations released the results of its two surveys on corruption in the judiciary; it published that: a) like 1995, 1/4 of lawyers said many/very many judges are corrupt. But (49%) stated that a judges received bribes, just 8% of lawyers admitted they reported the bribery, because they could not prove it. [Tables 8-9]; judges, however, said, just 7% call many/very many judges as corrupt[Tables 10-11];b) "Judges see some corruption; proportions who said - many/very many corrupt judges or justices: 17% in reference to RTC judges, 14% to MTC judges, 12% to Court of Appeals justices, 4% i to Shari'a Court judges, 4% to Sandiganbayan justices and 2% in reference to Supreme Court justices [Table 15].[29][30]

The September 14, 2008, Political and Economic Risk Consultancy (PERC) survey, ranked the Philippines 6th (6.10) among corrupt Asian judicial systems. PERC stated that "despite India and the Philippines being democracies, expatriates did not look favourably on their judicial systems because of corruption." PERC reported Hong Kong and Singapore have the best judicial systems in Asia, with Indonesia and Vietnam the worst: Hong Kong's judicial system scored 1.45 on the scale (zero representing the best performance and 10 the worst); Singapore with a grade of 1.92, followed by Japan (3.50), South Korea (4.62), Taiwan (4.93), the Philippines (6.10), Malaysia (6.47), India (6.50), Thailand (7.00), China (7.25), Vietnam's (8.10) and Indonesia (8.26).[31]<[32]

In 2014, Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (global survey ranking countries in terms of perceived corruption), the Philippines ranked 85th out of 175 countries surveyed, an improvement from placing 94th in 2013. It scored 38 on a scale of 1 to 100 in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).[33]

The Philippines jumped nine places in the recently published World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index 2015, making it one of the most improved countries in terms of global rankings. It ranked 51st out of 102 countries on the ROLI, a significant jump from last year when the country ranked 60th out of 99 countries. This makes the Philippines the most improved among ASEAN member nations. "Results showed that the country ranked high in terms of constraints on government powers (39th); absence of corruption (47th), and open government (50th)."

"The Philippines, however, fell to the bottom half of the global rankings in terms of regulatory enforcement (52nd); order and security (58th); criminal justice (66th); fundamental rights (67th), and civil justice (75th)."[34]

Bantay Korte Suprema

[edit]"Watch the Supreme Court" coalition was launched at the Training Center, Ground Floor, Supreme Court Centennial Bldg on November 17, 2008, "to ensure the fair and honest selection of the 7 Associate Justices of the Supreme Court on 2009." Members of “Bantay Korte Suprema” include retired Philippine presidents, retired Supreme Court justices, legislators, legal practitioners, the academe, the business community and the media. former Senate President Jovito Salonga, UP Law Dean Marvic Leonen, Senate Majority Leader and Judicial and Bar Council member Kiko Pangilinan, the Philippine Bar Association, Artemio Panganiban, and Rodolfo Urbiztondo, of the 48,000-strong Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP), and the chambers of commerce, witnessed the landmark event. BKS will neither select nor endorse a candidate, “but if it receive information that makes a candidate incompetent, it will divulge this to the public and inform the JBC." At the BKS launching, the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on the public monitoring of the selection of justices to the SC was signed.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court Appointments Watch (SCAW) coalition of law groups and civil society to monitor the appointment of persons to judicial positions was also re-launched. The SCAW consortium, composed of the Alternative Law Groups, Libertas, Philippine Association of law Schools and the Transparency and Accountability Network, together with the online news magazine Newsbreak, reactivated itself for the JBC selection process of candidates.[35][36][37][38]

Landmark decision (selection)

[edit]- Republic v. Sereno (2018, removal of an impeachable official via quo warranto petition)

- Lagman et al. vs. Senate President Pimentel et. al. (2017, validity of second extension of the proclamation of martial law in entire Mindanao for one year)

- Knights of Rizal v. DMCI (2017, suspension of the construction, and ultimate demolition of the condominium building for violating National Cultural Heritage Act)

- Saturnino C. Ocampo, et al. v. Rear Admiral Ernesto C. Enriquez, et al (2016, Constitutional validity of internment of the remains of President Ferdinand Marcos to the Libingan ng mga Bayani)

- David v. Poe (2015, eligibility of a foundling for public office)

- League of Cities of the Philippines vs. COMELEC (2011, validity of the cityhood laws of sixteen municipalities)

- Biraogo vs. Philippine Truth Commission (2010, validity of the creation of the Truth Commission)

- Quinto vs. COMELEC (2009, incumbent appointive executive officials to stay in office after filing their certificates of candidacy for election to an elective officials)

- Sema vs. COMELEC (2008, power of the autonomous region to create provinces and cities)

- Neri vs. Senate (2008, validity of extension of executive privilege to cabinet officials)

- Re: Letter of Presiding Justice Conrado M. Vasquez, Jr. on CA-G.R. SP NO. 103692 (2008, Irregularities and improprieties committed by the C.A. Justices in connection with the MERALCO case)

- People v Estrada (2007, charging the former president for the offense of Plunder)

- Oposa v. Factoran (1993, Doctrine of Intergenerational Responsibility on the environment in the Philippine legal system)

- Javellana v. Executive Secretary (1974, ratification of the 1973 Constitution)

- People vs. Hernandez (1956, rebellion is charged as a single offense rather than complex crime)

- Krivenko v Register of Deeds (1947, prohibition of foreign acquisition of private or public agricultural lands, including residential lands)

Notes

[edit]- a. ^ Art. VIII of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines.

- b. ^ §9, supra.

- c. ^ §8(5), supra.

- d. ^ §7(1), supra.

- e. ^ §7(3), supra.

- f. ^ This was changed to 65 from 1973 to 1978, but since restored to 70.

- g. ^ §11, supra.

- h. ^ §5(4) & (5), supra.

- i. ^ §1, supra.

- j. ^ §1, 2 and 3, Rule 65 of the Rules of Civil Procedure of the Rules of Court.

- k. ^ Toh v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 140274 (November 15, 2000).

- l. ^ §6, Rule 45 of the Rules of Civil Procedure of the Rules of Court.

- n. ^ Art. VIII of the 1935 Constitution of the Philippines.

- o. ^ Art. V of the Treaty of General Relations and Protocol (also known as the Treaty of Manila of 1946).

- p. ^ §2(1), Art. X of the 1973 Constitution of the Philippines.

- q. ^ §4, supra.

- r. ^ Second paragraph of §1, Art. VIII of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines.

References

[edit]- ^ "XXX. The Judiciary of the General Appropriations Act F.Y. 2018-Volume IB" (PDF). Department of Budget and Management. December 29, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Supreme Court | History of the Supreme Court". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "A Constitutional History of the Supreme Court of the Philippines". Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Brion, J. Art. D. (June 13, 2017). "The Supreme Court at center stage". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Boncan, Celestina P. (February 6, 2013). "Beginnings: University of the Philippines Manila". University of the Philippines. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pangalangan, Raul C. (December 20, 2016). "I. Overview of the Philippine Judicial System". Institute of Developing Economies (in Japanese). Institute of Developing Economies–Japan External Trade Organization. pp. 1–5. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Census of the Philippine Islands: Taken Under the Direction of the Philippine Commission in the Year 1903, in Four Volumes. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1905. pp. 389–410. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ "The Judicial Branch". Official Gazette. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Act No. 136, (1901-06-11)". Lawyerly. June 11, 1901. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Han Dong-Man (June 10, 2018). "Supreme Court Day". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "The execution of Jose Abad Santos". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Torres-Tupas, Tetch (December 16, 2015). "Justice Florentino Feliciano passes away at 87". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ "A Chief Justice Sereno is win-win for P-Noy". Balita. August 14, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Rufo, Aries (September 30, 2008). "Exclusive: SC Justice Alicia Martinez to retire early". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Merueñas, Mark (November 4, 2015). "SC Justice Villarama seeks early retirement due to deteriorating health". GMA News. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Inquirer.net, 3 Bulacan courts to use Filipino in judicial proceedings Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernas, Joaquin G. (1996). The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines: A Commentary. Rex Book Store. p. 831. ISBN 9789712320132.

- ^ Inquirer.net, SC approves use of writ of amparo Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Inquiret.net, Military can’t shrug off killings--Chief Justice

- ^ ABS-CBN Interactive, SC ready with writ of amparo by Sept - Puno

- ^ Supremecourt.gov.ph, A.M. No. 07-9-12-SC, THE RULE ON THE WRIT OF AMPARO[permanent dead link]

- ^ S.C. Resolution, A.M. No. 07-9-12-SC, THE RULE ON THE WRIT OF AMPARO Archived 2008-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Supremecourt.gov.ph, SC Approves Rule on Writ of Amparo Archived 2007-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ GMA NEWS.TV, SC approves rule on writ of amparo vs extralegal killings

- ^ GMA NEWS.TV, Writ of amparo not enough – Hong Kong rights group

- ^ Inquirer.net, Habeas data: SC’s new remedy vs killings, disappearances

- ^ newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews, Supreme Court okays rules of ‘habeas data’

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

gov.phwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ www.sws.org.ph, New Diagnostic Study Sets Guideposts for Systematic Development of the Judiciary Archived 2015-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ www.sws.org.ph, New SWS Study of the Judiciary and the Legal Profession Sees Some Improvements, But Also Recurring Problems Archived 2015-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ afp.google.com/article, Hong Kong has best judicial system in Asia: business survey Archived 2011-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ www.abs-cbnnews.com, Hong Kong has best judicial system in Asia: business survey

- ^ PH improves rank in global corruption index

- ^ Inquirer.net PH is most improved in rule of law index

- ^ "newsinfo.inquirer.net, SC watchdog launched". Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ supremecourt.gov.ph, LAUNCHING OF BANTAY KORTE SUPREMA[permanent dead link]

- ^ gmanews.tv/story, Group launches ‘Bantay Korte Suprema’ to guard selection of new SC justices

- ^ balita.ph, Bantay Korte Suprema launched[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]- Philippines: Gov.Ph: About the Philippines – Judiciary

- The Supreme Court of the Philippines – Official website

Category:Government of the Philippines Philippines *Main Category:Courts in the Philippines