User:RL0919/Cultural

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

Ayn Rand (1905–1982), the Russian-born American writer and philosopher best known for her novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, has influenced politics and popular culture, despite a lack of acceptance for her work in academic circles.

Popular interest

[edit]

With over 37 million copies sold as of 2020[update], Rand's books continue to be read widely.[1][a] A survey conducted for the Library of Congress and the Book-of-the-Month Club in 1991 asked club members to name the most influential book in their lives. Rand's Atlas Shrugged was the second most popular choice, after the Bible.[3] Although Rand's influence has been greatest in the United States, there has been international interest in her work.[4][5]

Rand's works, most commonly Anthem or The Fountainhead, are sometimes assigned as secondary school reading.[6] Since 2002, the Ayn Rand Institute has provided free copies of Rand's novels to teachers who promise to include the books in their curriculum.[7] The Institute had distributed 4.5 million copies in the U.S. and Canada by the end of 2020.[2] In 2017, Rand was added to the required reading list for the A Level Politics exam in the United Kingdom.[8]

Literary influence

[edit]Rand's contemporary admirers included fellow novelists, like Ira Levin, Kay Nolte Smith[9] and L. Neil Smith;[10] she has influenced later writers like Erika Holzer (American novelist and essayist, whose books include Double Crossing, Eye for an Eye, and Ayn Rand: My Fiction-writing Teacher),[11][10] Terry Goodkind (American novelist best known for his series of fantasy novels, The Sword of Truth),[10][12] Kira Peikoff, (an American journalist and novelist)[13] and J. Neil Schulman (an American writer and filmmaker whose novels include Alongside Night and The Rainbow Cadenza);[14] and comic book artists Steve Ditko (American comic book artist and writer who created or co-created a number of characters, including Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, Question, the Creeper, and Mr. A)[15][16] and Frank Miller (American writer, artist, and film director whose works include Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Sin City).[16]

Business admirers

[edit]

Rand provided a positive view of business and subsequently many business executives and entrepreneurs have admired and promoted her work.[18] Businessmen such as John Allison (former CEO of BB&T) and Ed Snider (former chairman of Comcast Spectacor) have funded the promotion of Rand's ideas.[19][20] Other notable business executives who have acknowledged Rand's influence include former Cybex International chairman John Aglialoro,[21] Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban,[21] Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick,[22] former Gillette Company CEO James M. Kilts,[23] Whole Foods Market co-founder John Mackey,[21] Craigslist founder Craig Newmark,[22] hedge fund manager Victor Niederhoffer,[24] PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel,[22] former hedge fund manager Monroe Trout,[25] and Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales.[22]

Cultural depictions

[edit]Television shows, movies, songs, and video games have referred to Rand and her works.[26][27] Throughout her life she was the subject of many articles in popular magazines,[28] as well as book-length critiques by authors such as the psychologist Albert Ellis[29] and Trinity Foundation president John W. Robbins.[30] Rand or characters based on her figure prominently in novels by American authors,[31] including Kay Nolte Smith, Mary Gaitskill, Matt Ruff, and Tobias Wolff.[32] Nick Gillespie, former editor-in-chief of Reason, remarked that, "Rand's is a tortured immortality, one in which she's as likely to be a punch line as a protagonist. Jibes at Rand as cold and inhuman run through the popular culture."[33] Two movies have been made about Rand's life. A 1997 documentary film, Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[34] The Passion of Ayn Rand, a 1999 television adaptation of the book of the same name, won several awards.[35] Rand's image also appears on a 1999 U.S. postage stamp illustrated by artist Nick Gaetano.[36]

Political influence

[edit]Although she rejected the labels "conservative" and "libertarian",[37][38] Rand has had a continuing influence on right-wing politics and libertarianism.[39][40] Historian Jennifer Burns referred to her as "the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right".[39]

Rand is often considered one of the three most important women (along with Rose Wilder Lane and Isabel Paterson) in the early development of modern American libertarianism.[41][42] David Nolan, one founder of the Libertarian Party, said that "without Ayn Rand, the libertarian movement would not exist".[43] In his history of that movement, journalist Brian Doherty described her as "the most influential libertarian of the twentieth century to the public at large".[3] Political scientist Andrew Koppelman called her "the most widely read libertarian".[44] Several Libertarian presidential candidates have cited her as an influence, including 1972 nominee John Hospers,[14][45] 1984 nominee David Bergland,[46] 1988 nominee Ron Paul,[14][47] and 2008 nominee Bob Barr.[48]

Other political figures who cite Rand as an influence are usually conservatives (often members of the Republican Party),[49] despite Rand taking some atypical positions for a conservative, like being pro-choice and an atheist.[50] She faced intense opposition from William F. Buckley Jr. and other contributors to the conservative National Review magazine, which published numerous criticisms of her writings and ideas.[51] Nevertheless, a 1987 article in The New York Times referred to her as the Reagan administration's "novelist laureate".[52] Republican congressmen and conservative pundits have acknowledged her influence on their lives and have recommended her novels.[53][54][55] She has influenced some conservative politicians outside the U.S., such as Malcom Fraser in Australia,[56] Sajid Javid in the United Kingdom, Siv Jensen in Norway, and Ayelet Shaked in Israel.[57][58]

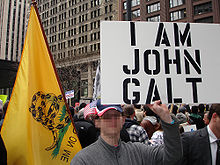

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 spurred renewed interest in her works, especially Atlas Shrugged, which some saw as foreshadowing the crisis.[59][60] Opinion articles compared real-world events with the novel's plot.[49][61] Signs mentioning Rand and her fictional hero John Galt appeared at Tea Party protests.[60] There was increased criticism of her ideas, especially from the political left. Critics blamed the economic crisis on her support of selfishness and free markets, particularly through her influence on Alan Greenspan.[55] In 2015, Adam Weiner said that through Greenspan, "Rand had effectively chucked a ticking time bomb into the boiler room of the US economy".[62] Lisa Duggan said that Rand's novels had "incalculable impact" in encouraging the spread of neoliberal political ideas.[63] In 2021, Cass Sunstein said Rand's ideas could be seen in the tax and regulatory policies of the Trump administration, which he attributed to the "enduring influence" of Rand's fiction.[64]

Objectivist movement

[edit]

After the closure of the Nathaniel Branden Institute, the Objectivist movement continued in other forms. In the 1970s, Peikoff began delivering courses on Objectivism.[65] In 1979, Peter Schwartz started a newsletter called The Intellectual Activist, which Rand endorsed.[66][67] She also endorsed The Objectivist Forum, a bimonthly magazine founded by Objectivist philosopher Harry Binswanger, which ran from 1980 to 1987.[68]

In 1985, Peikoff worked with businessman Ed Snider to establish the Ayn Rand Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting Rand's ideas and works. In 1990, after an ideological disagreement with Peikoff, David Kelley founded the Institute for Objectivist Studies, now known as The Atlas Society.[69][70] In 2001, historian John McCaskey organized the Anthem Foundation for Objectivist Scholarship, which provides grants for scholarly work on Objectivism in academia.[71]

Working lists of people for possible mention

[edit]Politics and economics people

[edit]- Paul Ryan[72] (1970– ), a Republican member of Congress from Wisconsin. He was the Republican nominee for Vice President of the United States in the 2012 election. In 2015 he became the 62nd Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

- Clarence Thomas[73] (1948– ), an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He previously served as an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Education, chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

- Martin Anderson[74] (1936–2015), an economist, policy analyst, author, and advisor to President Ronald Reagan.

- Walter Block[75] (1941– ), an American Austrian School economist and anarcho-capitalist theorist.

- Peter Boettke[76] (1960– ), an American economist of the Austrian School.

- Bryan Caplan[77] (1971– ), an American economist.

- Tyler Cowen[78] (1962– ), an American economist and writer. He is a professor at George Mason University and is co-author of the economics blog Marginal Revolution.

- Pamela Geller[79] (1958– ), an American political commentator and co-founder of the organization Stop Islamization of America.

- Matt Kibbe, President and Chief Community Organizer of Free the People, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting libertarian ideals

- Stephan Kinsella[80] (1965– ), an American intellectual property lawyer and author.

- Gordon McLendon[14] (1921–1986), radio pioneer and founder of the Liberty Broadcasting System.

- Mark Meckler[81] (1962– ), an American Tea Party activist who co-founded the Tea Party Patriots and later founded Citizens for Self-Governance.

- Mary Ruwart[82] (1949– ), a retired biomedical researcher and libertarian author and activist.

- Joseph T. Salerno[83] (1950– ), an American economist of the Austrian School, who is a professor and chair of the economics graduate program at Pace University.

- Larry J. Sechrest[84] (1946–2008), an American economist of the Austrian School, who advocated free banking and anarcho-capitalism.

- Joseph Sobran[85] (1946–2010), an American journalist.

- John Stossel[86] (1947– ), an American author and television journalist. He hosts the show Stossel on the Fox Business Channel.

- Alex Tabarrok[87] (1966– ), an American economist and writer. He is a professor at George Mason University and is co-author of the economics blog Marginal Revolution.

Philosophy people and other intellectuals

[edit]Objectivists/ish

[edit]- Andrew Bernstein[88] (1949– ), a professor of philosophy.

- Harry Binswanger[89] (1944– ), an American philosopher and former editor of The Objectivist Forum.

- Allan Gotthelf[14] (1942–2013), an American philosopher whose books include On Ayn Rand.

- Stephen Hicks[90] (1960– ), a Canadian-American philosopher.

- Michelle Marder Kamhi, an American art critic and co-author of the book What Art Is: The Esthetic Theory of Ayn Rand.

- David Kelley[14] (1949– ), an American philosopher. In 1990 he founded the Institute for Objectivist Studies (later renamed The Atlas Society) to promote Objectivism.

- James G. Lennox[91] (1948– ), a professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh.

- John David Lewis[92] (1955–2012), a political scientist, historian and Objectivist scholar.

- Edwin A. Locke[14] (1938– ), an American psychologist and a pioneer in goal-setting theory.

- Tibor R. Machan[14][94] (1939–2016), a Hungarian American philosopher who taught at Auburn University.

- Fred Miller,[14] an emeritus professor of philosophy at Bowling Green State University.

- Amy Peikoff[95] (c. 1968– ), an American writer and academic.

- Leonard Peikoff[96] (1933– ), a Canadian-American philosopher and Rand's legal heir. He founded the Ayn Rand Institute in 1985. His books include The Ominous Parallels and Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.

- John Ridpath[14] (1936–2021), a Canadian intellectual historian. He was one of the directors of the Ayn Rand Institute from 1994 to 2011.

- Chris Matthew Sciabarra[97] (1960– ), an American political theorist whose works include Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. He is the co-founder of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies.

- George H. Smith[14] (1949– ), an American author. His works include Atheism: The Case Against God (1974) and Atheism, Ayn Rand and Other Heresies (1991).

- Tara Smith[98] (1961– ), a professor of philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin. Her works include Ayn Rand's Normative Ethics: The Virtuous Egoist, and she is on the board of directors of the Ayn Rand Institute.

Others

[edit]- Anton LaVey[99] (1930–1997), founder of the Church of Satan.

- Liu Junning[100] (1961– ), a Chinese political scientist.

- Roderick T. Long[101] (1964– ), an American professor of philosophy at Auburn University and a libertarian blogger. He is an editor of the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies.

- Douglas B. Rasmussen[14] (1948– ), an American philosopher and professor at St. John's University. He co-edited The Philosophic Thought of Ayn Rand, a 1984 collection of essays about Objectivism.

- Robert Ringer[14] (1938– ), an American author, entrepreneur, and motivational speaker.

Arts and literature people

[edit]Novelists

[edit]- Edward Cline[102][103] (1946– ), an American novelist and essayist.

- Hunter S. Thompson[104] (1937–2005), an American author and founder of the gonzo journalism movement. His works include Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and The Rum Diary.

Actors and filmmakers

[edit]- Jeff Britting[105] (1957– ), an American composer, playwright, author, and producer. He worked on the 1997 documentary Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life.

- Amber Heard[106] (1986– ), an American television and movie actress.

- Michael Paxton[107] (1957– ), an American filmmaker who directed the documentary Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life.

- Selvaraghavan Kasthuri Raja[108] (1975– ), an Indian film director, producer, script writer, screenwriter and lyricist who works mostly in Tamil language and Telugu language films.

- Mark Pellegrino[109] (1965– ), an American actor of film and television.

- Gene Roddenberry[110] (1921–1991), a screenwriter and producer who created the Star Trek franchise.

- Vince Vaughn[111] (1970– ), an American actor, screenwriter, and producer.

Other artists

[edit]- Bosch Fawstin,[112] an Eisner nominated American cartoonist

- Penn Jillette[21] (1955– ), an American entertainer and author best known for his work in the stage magic team Penn & Teller.

- Neil Peart[14] (1952–2020), the drummer and primary lyricist for the rock band Rush.

Notes

[edit]- ^ This total includes 4.5 million copies purchased for free distribution to schools by the Ayn Rand Institute (ARI).[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Offord 2022, p. 12.

- ^ a b "Ayn Rand Institute Annual Report 2020". Ayn Rand Institute. December 20, 2020. p. 17 – via Issuu.

- ^ a b Doherty 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, pp. 384–386.

- ^ Murnane 2018, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "An Introduction to the Study of Ayn Rand". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Duffy 2012.

- ^ Wang 2017.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 310.

- ^ a b c Riggenbach 2004, pp. 91–144.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 310, 420.

- ^ Gelder, Ken (2004). Popular Fiction: The Logics and Practices of a Literary Field. New York: Routledge. p. 157n2. ISBN 0-415-35646-6.

- ^ "Book Brahmin: Kira Peikoff". Shelf Awareness. March 30, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Branden 1986, p. 416.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, pp. 8–11.

- ^ a b Gladstein 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Runciman 2009.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 168–171.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 298.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 412.

- ^ a b c d Merrill 2013, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Murnane 2018, p. 46.

- ^ Merrill 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 99.

- ^ Walker 1999, p. 333.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 282.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 110–111.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 98.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Brühwiler 2021, pp. 15–22.

- ^ Chadwick & Gillespie 2005, at 1:55.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Wozniak 2001, p. 380.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 258.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 55.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 107–108, 124.

- ^ Burns 2015, p. 746.

- ^ Brühwiler 2021, p. 88.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 414.

- ^ Koppelman 2022, p. 17.

- ^ Block 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Block 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Block 2010, p. 259.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 124.

- ^ a b Doherty 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Burns 2004, pp. 139, 243.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. xii.

- ^ Doherty 2009, p. 51.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Brühwiler 2021, pp. 174–184.

- ^ Rudoren 2015.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b Doherty 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Weiner 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Duggan 2019, p. xiii.

- ^ Sunstein 2021, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Sciabarra 2013, p. 402 n5.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 276.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 79.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 19, 114.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Merrill 2013, p. 5

- ^ Thomas, Clarence (2007). My Grandfather's Son: A Memoir. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 62, 187. ISBN 978-0-06-056556-5. OCLC 191930033.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 310

- ^ Block 2010, p. 52

- ^ Block 2010, p. 61

- ^ Block 2010, p. 73

- ^ Block 2010, p. 92

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 130

- ^ Block 2010, p. 167

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 148

- ^ Block 2010, p. 305

- ^ Block 2010, pp. 307, 309

- ^ Block 2010, p. 331

- ^ Block 2010, p. 341

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 112

- ^ Block 2010, p. 349

- ^ "Andrew Bernstein: Bio". Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ McConnell, Scott (2010). 100 Voices:An Oral History of Ayn Rand. New York: New American Library. pp. 575–611. ISBN 978-0-451-23130-7. OCLC 555642813.

- ^ Merrill 2013, p. 196

- ^ Lennox, James. "Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ "In Memoriam: John David Lewis, 1955–2012". January 5, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Block 2010, p. 216

- ^ Block 2010, p. 217

- ^ Peikoff, Amy. "Amy". Don't Let It Go Unheard. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gladstein-p95was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Block 2010, p. 327

- ^ Merrill 2013, p. 49

- ^ Ellis, Bill (2000). Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 172, 180. ISBN 0-8131-2170-1.

As for his 'religion,' he called it 'just Ayn Rand's philosophy, with ceremony and ritual added'...

- ^ "Liu Junning". Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ^ Block 2010, p. 197

- ^ Da Cunha, Mark (June 30, 2011). "Capitalism Magazine Interview with Edward Cline". Capitalism Magazine. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Kline, Edward. "Edward Cline, American Novelist". Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Hunter S. (April 7, 1998). The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, 1955–1967 (The Fear and Loathing Letters, Vol. 1). Ballantine Books. pp. 69–70. ISBN 0345377966.

- ^ "Jeff Britting". Ayn Rand Institute. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ Keck, William (May 30, 2007). "Amber Heard Will be Heard". USA Today. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ Walker 1999, p. 193.

- ^ Fully Filmy (December 3, 2016), "I don't want interference in my life" – Fully Frank with Selvaraghavan | Part 1 | Fully Filmy, retrieved December 24, 2016

- ^ "Mark Pellegrino on the American Capitalist Party". The Objective Standard. August 13, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Merrill 2013, p. 9.

- ^ "An Interview with Vince Vaughn". Judd Handler. 1999. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013.

The last book I read was the book I've been rereading most of my life, The Fountainhead.

- ^ Jones, Robert. "Bosch Fawstin: Infidel Artist". The Atlas Society. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

Works cited

[edit]- Branden, Barbara (1986). The Passion of Ayn Rand. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 978-0-385-19171-5.

- Brühwiler, Claudia Franziska (2021). Out of a Gray Fog: Ayn Rand's Europe (Kindle ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-79363-686-7.

- Burns, Jennifer (November 2004). "Godless Capitalism: Ayn Rand and the Conservative Movement". Modern Intellectual History. 1 (3): 359–385. doi:10.1017/S1479244304000216. S2CID 145596042.

- Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7.

- Burns, Jennifer (December 2015). "The Three 'Furies' of Libertarianism: Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, and Ayn Rand". The Journal of American History. 102 (3): 746–774. doi:10.1093/jahist/jav504.

- Chadwick, Alex & Gillespie, Nick (February 2, 2005). "Book Bag: Marking the Ayn Rand Centennial". Day to Day. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- Doherty, Brian (2007). Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement. New York: Public Affairs Press. ISBN 978-1-58648-350-0.

- Doherty, Brian (December 2009). "She's Back!". Reason. Vol. 41, no. 7. pp. 51–58.

- Duffy, Francesca (August 20, 2012). "Teachers Stocking Up on Ayn Rand Books". Education Week. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- Duggan, Lisa (2019). Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-96779-3.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (1999). The New Ayn Rand Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30321-0.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (Spring 2003). "Ayn Rand Literary Criticism". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 4 (2): 373–394. JSTOR 41560226.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (2009). Ayn Rand. Major Conservative and Libertarian Thinkers. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-4513-1.

- Gotthelf, Allan & Salmieri, Gregory, eds. (2016). A Companion to Ayn Rand. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8684-1.

- Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9.

- Koppelman, Andrew (2022). Burning Down the House: How Libertarian Philosophy Was Corrupted by Delusion and Greed (Kindle ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-28014-5.

- Murnane, Ben (2018). Ayn Rand and the Posthuman: The Mind-Made Future. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-90853-3.

- Offord, Derek (2022). Ayn Rand and the Russian Intelligentsia: The Origins of an Icon of the American Right. Russian Shorts (Kindle ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-3502-8393-0.

- Riggenbach, Jeff (Fall 2004). "Ayn Rand's Influence on American Popular Fiction". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 91–144. JSTOR 41560271.

- Rudoren, Jodi (May 15, 2015). "Ayelet Shaked, Israel's New Justice Minister, Shrugs Off Critics in Her Path". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Runciman, David (May 28, 2009). "Like Boiling a Frog". London Review of Books. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 2004). "The Illustrated Rand". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 1–20. JSTOR 41560268.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (2013). Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical (2nd ed.). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-06374-4.

- Sunstein, Cass R. (2021). This Is Not Normal: The Politics of Everyday Expectations. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25350-4.

- Wang, Amy X. (March 27, 2017). "Ayn Rand's 'Objectivist' Philosophy Is Now Required Reading for British Teens". Quartz. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- Weiner, Adam (2020) [2016]. How Bad Writing Destroyed the World: Ayn Rand and the Literary Origins of the Financial Crisis (Kindle ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-5013-1314-1.

- Weiss, Gary (2012). Ayn Rand Nation: The Hidden Struggle for America's Soul. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-59073-4.

- Wozniak, Maurice D., ed. (2001). Krause-Minkus Standard Catalog of U.S. Stamps (5th ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-321-5.

More works cited

[edit]- Block, Walter, ed. (2010). I Chose Liberty: Autobiographies of Contemporary Libertarians. Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 978-1-61016-002-5.

- Merrill, Ronald E. (2013). Ayn Rand Explained: From Tyranny to Tea Party. Revised and updated by Marsha Familaro Enright. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9798-8.

- Walker, Jeff (1999). The Ayn Rand Cult. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 0-8126-9390-6. OCLC 39914039.

External links

[edit]- Celebrity Rand Fans – archive of links to articles about "fans" of Rand