User:Pandemics/Spanish flu

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

The 1918 influenza pandemic (January 1918 – December 1920; colloquially known as Spanish flu) was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic, the first of the two pandemics involving H1N1 influenza virus.[1] It infected 500 million people around the world,[2] including people on remote Pacific islands and in the Arctic. Probably 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million (three to five percent of Earth's population at the time) died, making it one of the deadliest epidemics in human history.[3][4][5] For reference, the 1918 influenza pandemic killed more than both WWI and WWII combined. In British India alone, it is estimated that 17 million people died.[6] However, the pandemic's exact geographic origin is still uncertain due to inadequate data, and there are still many competing theories.[2]

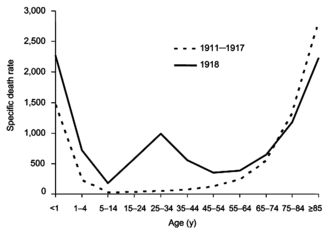

Infectious diseases already limited life expectancy in the early 20th century, but life expectancy in the United States dropped by about 12 years in the first year of the pandemic.[7][8][9] Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, with a higher survival rate for those in-between. However, the Spanish flu pandemic resulted in a higher than expected mortality rate for young adults.[10]

To maintain morale, wartime censors minimized early reports of illness and mortality in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and the United States.[11][12] Papers were free to report the epidemic's effects in neutral Spain (such as the grave illness of King Alfonso XIII).[13] These stories created a false impression of Spain as especially hard hit,[14] thereby giving rise to the pandemic's nickname, "Spanish flu".[15]

Scientists offer several possible explanations for the high mortality rate of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Some analyses have shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a cytokine storm, which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults.[16] In contrast, a 2007 analysis of medical journals from the period of the pandemic[17][18] found that the viral infection was no more aggressive than previous influenza strains. Instead, malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene promoted bacterial superinfection. This superinfection killed most of the victims, typically after a somewhat prolonged death bed.[19][20]

History

[edit]Hypotheses about the source

[edit]The major troop staging and hospital camp in Étaples, France, was identified by researchers as being at the center of the Spanish flu. The research was published in 1999 by a British team, led by virologist John Oxford.[21] In late 1917, military pathologists reported the onset of a new disease with high mortality that they later recognized as the flu. The overcrowded camp and hospital was an ideal site for the spreading of a respiratory virus. The hospital treated thousands of victims of chemical attacks, and other casualties of war. 100,000 soldiers were in transit through the camp every day. It also was home to a live piggery, and poultry was regularly brought in for food supplies from surrounding villages. Oxford and his team postulated that a significant precursor virus, harbored in birds, mutated and then migrated to pigs kept near the front.[22][23]

There have been claims that the epidemic originated in the United States. Historian Alfred W. Crosby claimed that the flu originated in Kansas,[24] and popular author John M. Barry described Haskell County, Kansas, as the point of origin.[16] It has also been claimed that, by late 1917, there had already been a first wave of the epidemic in at least 14 US military camps.[25] Political scientist Andrew Price-Smith published data from the Austrian archives suggesting the influenza had earlier origins, beginning in Austria in early 1917.[26]

One of the few regions of the world that were seemingly less affected by the 1918 flu pandemic was China, where there was a comparatively mild flu season in 1918.[27][28][29][30][31] There were relatively few deaths from the flu in China compared to other regions of the world.[32][33] This has led to speculation that the 1918 flu pandemic originated from the country of China itself.[34][35][36][37] The milder flu season and lower rates of flu mortality in China in 1918 may be explained due to the fact that the Chinese population had already possessed acquired immunity to the flu virus.[38] In 1918, there was apparently greater resistance to the virus among the Chinese population compared to other regions of the world, possibly meaning the Chinese people had already been exposed to the virus before.[39][40] East Asia is a common area for transmission of disease from animals to humans because of dense living conditions.[41] Claude Hannoun, the leading expert on the 1918 flu for the Pasteur Institute, asserts the former virus was likely to have come from China. It then mutated in the United States near Boston and spreading to Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, Europe, and the world via Allied soldiers and sailors as the main spreaders.[42]Hannoun considered several other hypotheses of origin, such as Spain, Kansas (United States), and Brest, as being possible, but not likely.

In 2014, historian Mark Humphries argued that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines might have been the source of the pandemic. Humphries, of the Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John's, based his conclusions on newly unearthed records. He found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.[43][44] However, a report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, found no evidence that the 1918 virus was imported to Europe via Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers. The Chinese report found evidence that the virus had been circulating in the European armies for months and possibly years before the 1918 pandemic.[45]

Spread

[edit]When an infected person sneezes or coughs, more than half a million virus particles can spread to those nearby.[46] The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have increased the lethality of the virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.[47][48]

A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of this flu was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease.[49]

In the United States, the disease was first observed in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the U.S. Public Health Service's academic journal. On 4 March 1918, company cook Albert Gitchell reported sick at Fort Riley, an American military facility that at the time was training American troops during World War I, making him the first recorded victim of the flu.[50][51] Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick.[52] By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York.[49] Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticised.[4]

In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France; in Freetown, Sierra Leone; and in the U.S. in Boston, Massachusetts. The Spanish flu also spread through Ireland, carried there by returning Irish soldiers. The Allies of World War I came to call it the Spanish flu, primarily because the pandemic received greater press attention after it moved from France to Spain in November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed wartime censorship.[53]

Mortality

[edit]Around the globe

[edit]

The global mortality rate from the 1918/1919 pandemic is not known, but an estimated 10% to 20% of those who were infected died. With about a third of the world population infected, this case-fatality ratio means 3% to 6% of the entire global population died.[2] Influenza may have killed as many as 25 million people in its first 25 weeks. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people,[3] while current estimates put the death toll at probably 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million.[56][5] These estimates would correspond to three to five percent of Earth's human population at the time.[57]

This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed more people than the Black Death.[58] This flu killed more people in 24 weeks than HIV/AIDS killed in 24 years, and more in a year than the Black Death killed in a century.[59] However, the Black Death killed a much higher percentage of the world's then smaller population.[60]

The disease killed in every area of the globe. As many as 17 million people died in India, about 5% of the population.[61] The death toll in India's British-ruled districts was 13.88 million.[62]

In Japan, of the 23 million people who were affected, 390,000 died.[63] In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died among 30 million inhabitants.[64] In Tahiti, 13% of the population died during one month. Similarly, in Samoa 22% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.[65]

In New Zealand, the flu killed an estimated 6,400 Europeans and 2,500 indigenous Maori in six weeks. [66] Dr. Geoffrey Rice has found that Maori died at eight times the rate of Pakeha.[67]

In Iran, the mortality was very high: according to an estimate, between 902,400 and 2,431,000, or 8.0% to 21.7% of the total population died.[68]

In the U.S., about 28% of the population became infected, and 500,000 to 675,000 died.[69] Native American tribes were particularly hit. In the Four Corners area, there were 3,293 registered deaths among Native Americans.[70] Entire Inuit and Alaskan Native village communities died in Alaska.[71] In Canada, 50,000 died.[72] In Brazil, 300,000 died, including president Rodrigues Alves.[73] In Britain, as many as 250,000 died; in France, more than 400,000.[74] In Ghana, the influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people.[75] Tafari Makonnen (the future Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia) was one of the first Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived.[76][77] Many of his subjects did not; estimates for fatalities in the capital city, Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher.[78] In British Somaliland, one official estimated that 7% of the native population died.[79]

This huge death toll resulted from an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.[3] Symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred".[56] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia,[80][81] a common secondary infection associated with influenza. The virus also killed people directly by causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[81]

The unusually severe disease killed up to 20% of those infected, as opposed to the usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%.[2][56]

Patterns of fatality

[edit]The pandemic mostly killed young adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of pandemic influenza deaths in the U.S. occurred in people under 65, and nearly half in young adults 20 to 40 years old. In 1920, the mortality rate among people under 65 had decreased sixfold to half the mortality rate of people over 65, but still, 92% of deaths occurred in people under 65.[82] This is unusual since influenza is typically most deadly to weak individuals, such as infants under age two, adults over age 70, and the immunocompromised. In 1918, older adults may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the 1889–1890 flu pandemic, known as the "Russian flu".[83] According to historian John M. Barry, the most vulnerable of all – "those most likely, of the most likely", to die – were pregnant women. He reported that in thirteen studies of hospitalized women in the pandemic, the death rate ranged from 23% to 71%.[84] Of the pregnant women who survived childbirth, over one-quarter (26%) lost the child.[85]

Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.[86]

Modern analysis has shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's immune system), which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults.[16] One group of researchers recovered the virus from the bodies of frozen victims and transfected animals with it. The animals suffered rapidly progressive respiratory failure and death through a cytokine storm. The strong immune reactions of young adults were postulated to have ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune systems of children and middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths among those groups.[59]

In fast-progressing cases, mortality was primarily from pneumonia, by virus-induced lung consolidation. Slower-progressing cases featured secondary bacterial pneumonia, and possibly neural involvement that led to mental disorders in some cases. Some deaths resulted from malnourishment.

A study – conducted by He et al. – used a mechanistic modeling approach to study the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. They examined the factors that underlie variability in temporal patterns and their correlation to patterns of mortality and morbidity. Their analysis suggests that temporal variations in transmission rate provide the best explanation, and the variation in transmission required to generate these three waves is within biologically plausible values.[87]

Another study by He et al. used a simple epidemic model incorporating three factors to infer the cause of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. These factors were school opening and closing, temperature changes throughout the outbreak, and human behavioral changes in response to the outbreak. Their modeling results showed that all three factors are important, but human behavioral responses showed the most significant effects.[88]

Deadly second wave

[edit]

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much deadlier than the first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. By August, when the second wave began in France, Sierra Leone, and the United States,[89] the virus had mutated to a much deadlier form. As the PBS American Experience: Influenza 1918 episode says, October 1918 was the deadliest month of the whole pandemic.[citation needed]

This increased severity has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War.[90] In civilian life, natural selection favors a mild strain. Those who get very ill stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, natural selection was reversed. Soldiers with a mild strain stayed where they were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. The second wave began, and the flu quickly spread around the world again. Consequently, during modern pandemics, health officials pay attention when the virus reaches places with social upheaval (looking for deadlier strains of the virus).[91]

The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections had become immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu. This was most dramatically illustrated in Copenhagen, which escaped with a combined mortality rate of just 0.29% (0.02% in the first wave and 0.27% in the second wave) because of exposure to the less-lethal first wave.[92] For the rest of the population, the second wave was far more deadly; the most vulnerable people were those like the soldiers in the trenches – young previously healthy adults.[93]

Devastated communities

[edit]

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many adults were incapacitated that much of everyday life was hampered. Some communities closed all stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There were reports that healthcare workers could not tend the sick nor the gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.[94]

Several Pacific island territories were particularly hard-hit. The pandemic reached them from New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent ships, such as the SS Talune, carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand, the flu reached Tonga (killing 8% of the population), Nauru (16%), and Fiji (5%, 9,000 people).[95]

Worst affected was Western Samoa, formerly German Samoa, which had been occupied by New Zealand in 1914. 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women, and 10% of children died. By contrast, Governor John Martin Poyer prevented the flu from reaching American Samoa by imposing a blockade.[95] The disease spread fastest through the higher social classes among the indigenous peoples, because of the custom of gathering oral tradition from chiefs on their deathbeds; many community elders were infected through this process.[96]

In New Zealand, 8,573 deaths were attributed to the 1918 pandemic influenza, resulting in a total population fatality rate of 0.74%.[97] Māori were 10 times as likely to die as pākehā (Europeans), because of their poorer and more crowded housing, and rural population.[96]

In Ireland, the Spanish flu accounted for 10% of the total deaths in 1918.

Data analysis revealed 6,520 recorded deaths in Savannah-Chatham County, Georgia (population of 83,252) for the three-year period from January 1, 1917, to December 31, 1919. Of these deaths, influenza was specifically listed as the cause of death in 316 cases, representing 4.85% of all causes of death for the total time period.[98]

Less-affected areas

[edit]China experienced a relatively mild flu season in 1918 compared to other areas of the world.[99][100][101][102][31] This has led to speculation that the 1918 H1N1 strain of flu itself originated from China, and due to that there was greater resistance amongst the Chinese population due to acquired immunity from previous exposure.[103][104] However, the view that China's experience of the flu in 1918 was mild has also been challenged. Though there was no centralised collection of health statistics in the country at the time, some reports from its interior suggest that mortality rates from influenza were perhaps higher in at least a few locations in China in 1918. However, at the very least, there is very little evidence that China as a whole, was seriously affected by the flu - at the very least compared to other countries in the world.[105] Although medical records from China's interior are lacking, there was extensive medical data recorded in Chinese port-cities, such as then British-controlled Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Peking, Harbin and Shanghai. This data was collected by the Chinese Maritime Customs Service.[106] As a whole, accurate data from China's port cities show astonishingly low mortality rates compared to other cities in Asia.[107] For example, the British authorities at Hong Kong and Canton reported a mortality rate from influenza at a rate of 0.25% and 0.32%, much lower than the reported mortality rate of other cities in Asia, such as Calcutta or Bombay, where influenza was much more devastating.[108][109] Similarly, in the city of Shanghai - which had a population of over 2 million in 1918 - there were only 266 recorded deaths from influenza among the Chinese population in 1918.[110] If we extrapolate from the extensive data recorded from Chinese cities, the suggested mortality rate from influenza in China as a whole in 1918 was likely lower than 1% - much lower than the world average (which was around 3-5%).[111] In contrast, Japan and Taiwan had reported a mortality rate from influenza around 0.45% and 0.69% respectively, higher than the mortality rate collected from data in Chinese port cities, such as Hong Kong (0.25%), Canton (0.32%), and Shanghai.[112] Some researchers have proposed that traditional Chinese medicine may have played a role in the low influenza mortality rate in China.[113]

In Japan, 257,363 deaths were attributed to influenza by July 1919, giving an estimated 0.425% mortality rate, fairly low compared to the global average. The Japanese government severely restricted sea travel to and from the home islands when the pandemic struck.

In the Pacific, American Samoa[114] and the French colony of New Caledonia[115] also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines. In Australia, nearly 12,000 perished.[116]

Russia was in the grip of a civil war in 1918, and its death toll from influenza is unknown. In 1991, a paper published in the journal Bulletin of the History of Medicine estimated that 450,000 Russians died in the second wave, which would mean that the country was relatively mildly affected.[3] However, the same paper warned that this estimate was no more than "a shot in the dark". Hospital records from the then Russian city of Odessa, combined with research carried out by Russian epidemiologists in the 1950s, suggest that the real number was closer to 2.7 million.[117]

By the end of the pandemic, the isolated island of Marajó, in Brazil's Amazon River Delta had not reported an outbreak.[118]

Saint Helena also reported no deaths.[119]

Aspirin poisoning

[edit]In a 2009 paper published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, Karen Starko proposed that aspirin poisoning contributed substantially to the fatalities. She based this on the reported symptoms in those dying from the flu, as reported in the post mortem reports still available, and also the timing of the big "death spike" in October 1918. This occurred shortly after the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army and the Journal of the American Medical Association both recommended very large doses of 8 to 31 grams of aspirin per day as part of treatment. These levels will produce hyperventilation in 33% of patients, as well as lung edema in 3% of patients.[120] Starko also notes that many early deaths showed "wet," sometimes hemorrhagic lungs, whereas late deaths showed bacterial pneumonia. She suggests that the wave of aspirin poisonings was due to a "perfect storm" of events: Bayer's patent on aspirin expired, so many companies rushed in to make a profit and greatly increased the supply; this coincided with the Spanish flu; and the symptoms of aspirin poisoning were not known at the time.[120]

As an explanation for the universally high mortality rate, this hypothesis was questioned in a letter to the journal published in April 2010 by Andrew Noymer and Daisy Carreon of the University of California, Irvine, and Niall Johnson of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. They questioned the universal applicability of the aspirin theory, given the high mortality rate in countries such as India, where there was little or no access to aspirin at the time compared to the rate where aspirin was plentiful.[121] They concluded that "the salicylate [aspirin] poisoning hypothesis [was] difficult to sustain as the primary explanation for the unusual virulence of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic".[121] In response, Starko said there was anecdotal evidence of aspirin use in India and argued that even if aspirin over-prescription had not contributed to the high Indian mortality rate, it could still have been a factor for high rates in areas where other exacerbating factors present in India played less of a role.[122]

End of the pandemic

[edit]After the lethal second wave struck in late 1918, new cases dropped abruptly – almost to nothing after the peak in the second wave.[59] In Philadelphia, for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending 16 October, but by 11 November, influenza had almost disappeared from the city. One explanation for the rapid decline of the lethality of the disease is that doctors got better at preventing and treating the pneumonia that developed after the victims had contracted the virus; but John Barry stated in his book that researchers have found no evidence to support this.[16]

Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out[16] (see also "Deadly Second Wave", above).

Long-term effects

[edit]A 2006 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that "cohorts in utero during the pandemic displayed reduced educational attainment, increased rates of physical disability, lower income, lower socioeconomic status, and higher transfer payments compared with other birth cohorts."[123] A 2018 study found that the pandemic reduced educational attainment in populations.[124]

The flu has been linked to the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.[125]

Legacy

[edit]

Academic Andrew Price-Smith has made the argument that the virus helped tip the balance of power in the latter days of the war towards the Allied cause. He provides data that the viral waves hit the Central Powers before the Allied powers and that both morbidity and mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.[26]

Despite the high morbidity and mortality rates that resulted from the epidemic, the Spanish flu began to fade from public awareness over the decades until the arrival of news about bird flu and other pandemics in the 1990s and 2000s.[126] This has led some historians to label the Spanish flu a "forgotten pandemic".[24]

There are various theories of why the Spanish flu was "forgotten". The rapid pace of the pandemic, which, for example, killed most of its victims in the United States within less than nine months, resulted in limited media coverage. The general population was familiar with patterns of pandemic disease in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: typhoid, yellow fever, diphtheria, and cholera all occurred near the same time. These outbreaks probably lessened the significance of the influenza pandemic for the public.[127] In some areas, the flu was not reported on, the only mention being that of advertisements for medicines claiming to cure it.[128]

Also, the outbreak coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War.[129] Another explanation involves the age group affected by the disease. The majority of fatalities, from both the war and the epidemic, were among young adults. The number of war-related deaths of young adults may have overshadowed the deaths caused by flu. When people read the obituaries, they saw the war or postwar deaths and the deaths from the influenza side by side. Particularly in Europe, where the war's toll was high, the flu may not have had a tremendous psychological impact or may have seemed an extension of the war's tragedies.[82] The duration of the pandemic and the war could have also played a role. The disease would usually only affect a particular area for a month before leaving. The war, however, had initially been expected to end quickly but lasted for four years by the time the pandemic struck.

Regarding global economic effects, many businesses in the entertainment and service industries suffered losses in revenue, while the healthcare industry reported profit gains.[130]

Historian Nancy Bristow has argued that the pandemic, when combined with the increasing number of women attending college, contributed to the success of women in the field of nursing. This was due in part to the failure of medical doctors, who were predominantly men, to contain and prevent the illness. Nursing staff, who were mainly women, celebrated the success of their patient care and did not associate the spread of the disease with their work.[131]

In Spain, sources from the period explicitly linked the Spanish flu to the cultural figure of Don Juan. The nickname for the flu, the "Naples Soldier", was adopted from Federico Romero and Guillermo Fernández Shaw's operetta, The Song of Forgetting (La canción del olvido). The protagonist of the operetta was a stock Don Juan type. Federico Romero, one of the librettists, quipped that the play's most popular musical number, Naples Soldier, was as catchy as the flu. Davis argued the Spanish flu–Don Juan connection allowed Spaniards to make sense of their epidemic experience by interpreting it through their familiar Don Juan story.[132]

Spanish flu research

[edit]

The origin of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the relationship between the near-simultaneous outbreaks in humans and swine, have been controversial. One hypothesis is that the virus strain originated at Fort Riley, Kansas, in viruses in poultry and swine which the fort bred for food; the soldiers were then sent from Fort Riley around the world, where they spread the disease.[133] Similarities between a reconstruction of the virus and avian viruses, combined with the human pandemic preceding the first reports of influenza in swine, led researchers to conclude the influenza virus jumped directly from birds to humans, and swine caught the disease from humans.[134][135]

Others have disagreed,[136] and more recent research has suggested the strain may have originated in a nonhuman, mammalian species.[137] An estimated date for its appearance in mammalian hosts has been put at the period 1882–1913.[138] This ancestor virus diverged about 1913–1915 into two clades (or biological groups), which gave rise to the classical swine and human H1N1 influenza lineages. The last common ancestor of human strains dates to between February 1917 and April 1918. Because pigs are more readily infected with avian influenza viruses than are humans, they were suggested as the original recipients of the virus, passing the virus to humans sometime between 1913 and 1918.

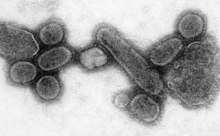

An effort to recreate the 1918 flu strain (a subtype of avian strain H1N1) was a collaboration among the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the USDA ARS Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, and Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. The effort resulted in the announcement (on 5 October 2005) that the group had successfully determined the virus's genetic sequence, using historic tissue samples recovered by pathologist Johan Hultin from a female flu victim buried in the Alaskan permafrost and samples preserved from American soldiers.[139]

On 18 January 2007, Kobasa et al. (2007) reported that monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) infected with the recreated flu strain exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic, and died from cytokine storms[140]—an overreaction of the immune system. This may explain why the 1918 flu had its surprising effect on younger, healthier people, as a person with a stronger immune system would potentially have a stronger overreaction.[141]

On 16 September 2008, the body of British politician and diplomat Sir Mark Sykes was exhumed to study the RNA of the flu virus in efforts to understand the genetic structure of modern H5N1 bird flu. Sykes had been buried in 1919 in a lead coffin which scientists hoped had helped preserve the virus.[142] The coffin was found to be split because of the weight of soil over it, and the cadaver was badly decomposed. Nonetheless, samples of lung and brain tissue were taken through the split, with the coffin remaining in situ in the grave during this process.[143]

In December 2008, research by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin linked the presence of three specific genes (termed PA, PB1, and PB2) and a nucleoprotein derived from 1918 flu samples to the ability of the flu virus to invade the lungs and cause pneumonia. The combination triggered similar symptoms in animal testing.[144]

In June 2010, a team at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported the 2009 flu pandemic vaccine provided some cross-protection against the 1918 flu pandemic strain.[145]

One of the few things known for certain about the influenza in 1918 and for some years after was that it was, out of the laboratory, exclusively a disease of human beings.[146]

In 2013, the AIR Worldwide Research and Modeling Group "characterized the historic 1918 pandemic and estimated the effects of a similar pandemic occurring today using the AIR Pandemic Flu Model". In the model, "a modern day "Spanish flu" event would result in additional life insurance losses of between US$15.3–27.8 billion in the United States alone", with 188,000–337,000 deaths in the United States.[147]

In 2018, Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biology professor at Arizona University who is examining the history of the 1918 pandemic, revealed that he obtained tissue slides created by William Rolland, a physician who reported on a respiratory illness likely to be the virus while a pathologist in the British military during World War I.[148] Rolland had authored an article in the Lancet during 1917 about a respiratory illness outbreak beginning in 1916 in Étaples, France.[149] Worobey traced recent references to that article to family members who had retained slides that Rolland had prepared during that time. Worobey is planning to extract tissue from the slides that may reveal more about the origin of the pathogen.

Gallery

[edit]-

Two American Red Cross nurses demonstrating treatment practices during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

-

Albertan farmers wearing masks to protect themselves from the flu.

-

Policemen wearing masks provided by the American Red Cross in Seattle, 1918

-

A street car conductor in Seattle in 1918 refusing to allow passengers aboard who are not wearing masks

-

Red Cross workers remove a flu victim in St. Louis, Missouri (1918)

-

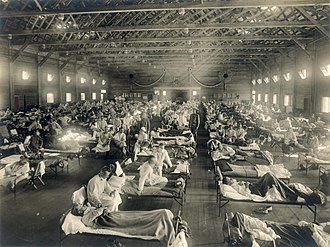

Influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1919

-

Burying flu victims, North River, Newfoundland and Labrador (1918)

-

1919 Tokyo, Japan

-

Japanese poster in 1919

-

Demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C., during the influenza pandemic of 1918

-

Cavalry memorial on the hill Lueg, memory of the Bernese cavalrymen victims of the 1918 flu pandemic; Emmental, Bern, Switzerland

-

The Spanish flu as the Naples Soldier (Spain, 1918)

-

Spanish biologists and the flu microbe (Spain, 1918)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "La Grippe Espagnole de 1918" (in French). Institut Pasteur. Archived from the original (Powerpoint) on 17 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Taubenberger & Morens 2006.

- ^ a b c d Patterson & Pyle 1991.

- ^ a b Billings 1997.

- ^ a b Johnson & Mueller 2002.

- ^ Mayor, S. (2000). "Flu experts warn of need for pandemic plans". British Medical Journal. 321 (7265): 852. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.852. PMC 1118673. PMID 11021855.

- ^ "The Nation's Health". www.flu.gov. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Life Expectancy". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Life expectancy in the USA, 1900–98". demog.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 8 June 2003. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ Gagnon A, Miller MS, Hallman SA, Bourbeau R, Herring DA, Earn DJ, Madrenas J (2013). "Age-Specific Mortality During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Unravelling the Mystery of High Young Adult Mortality". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e69586. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869586G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069586. PMC 3734171. PMID 23940526.

- ^ Valentine 2006.

- ^ Anderson, Susan (29 August 2006). "Analysis of Spanish flu cases in 1918–1920 suggests transfusions might help in bird flu pandemic". American College of Physicians. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Porras-Gallo & Davis 2014.

- ^ Barry 2004, p. 171. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBarry2004 (help)

- ^ Galvin 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Barry 2004b.

- ^ MacCallum, W.G. (1919). "Pathology of the pneumonia following influenza". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 72 (10): 720–723. doi:10.1001/jama.1919.02610100028012.

- ^ Hirsch, Edwin F.; McKinney, Marion (1919). "An epidemic of pneumococcus broncho-pneumonia". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 24 (6): 594–617. doi:10.1093/infdis/24.6.594.

- ^ Brundage JF, Shanks GD (December 2007). "What really happened during the 1918 influenza pandemic? The importance of bacterial secondary infections". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196 (11): 1717–8, author reply 1718–9. doi:10.1086/522355. PMID 18008258.

- ^ Morens DM, Fauci AS (April 2007). "The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 195 (7): 1018–28. doi:10.1086/511989. PMID 17330793.

- ^ "EU Research Profile on Dr. John Oxford". Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ Connor, Steve, "Flu epidemic traced to Great War transit camp", The Guardian (UK), Saturday, 8 January 2000. Accessed 2009-05-09. Archived 11 May 2009.

- ^ Oxford JS, Lambkin R, Sefton A, Daniels R, Elliot A, Brown R, Gill D (January 2005). "A hypothesis: the conjunction of soldiers, gas, pigs, ducks, geese and horses in northern France during the Great War provided the conditions for the emergence of the "Spanish" influenza pandemic of 1918-1919". Vaccine. 23 (7): 940–5. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.035. PMID 15603896.

- ^ a b Crosby 2003.

- ^ "How the US Army infected the World with Spanish Flu". Limpia por dentro. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ a b Price-Smith 2008.

- ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. 31 (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 3401475.

- ^ Cheng, K. F.; Leung, P. C. (1 July 2007). "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11 (4): 360–364. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 17379558.

- ^ Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R.; Krewski, Daniel (6 December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ a b Iijima W. "Spanish influenza in China, 1918–1920: a preliminary probe" in Phillips H, Killingray D eds. (2003) pp. 101-109

- ^ Cheng, K.F. "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 11, Issue 4, July 2007: 360-364.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sep., 2005) (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. JSTOR 3401475.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Cheng, K.F. "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 11, Issue 4, July 2007: 360-364.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sep., 2005) (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. JSTOR 3401475.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Klein, Christopher. "China Epicenter of 1918 Flu Pandemic, Historian Says".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vergano, Dan. "1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say". National Geographic.

- ^ Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R.; Krewski, Daniel (6 December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ^ Cheng, K.F. "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 11, Issue 4, July 2007: 360-364.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sep., 2005) (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. JSTOR 3401475.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ 1918 killer flu secrets revealed. BBC News. 5 February 2004.

- ^ Hannoun, Claude, "La Grippe", Ed Techniques EMC (Encyclopédie Médico-Chirurgicale), Maladies infectieuses, 8-069-A-10, 1993. Documents de la Conférence de l'Institut Pasteur : La Grippe Espagnole de 1918.

- ^ Humphries 2014.

- ^ Vergano, Dan (24 January 2014). "1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say". National Geographic. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Shanks GD (January 2016). "No evidence of 1918 influenza pandemic origin in Chinese laborers/soldiers in France". Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 79 (1): 46–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2015.08.009. PMID 26542935. S2CID 40028794.

- ^ Sherman IW (2007). Twelve diseases that changed our world. Washington, DC: ASM Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-55581-466-3.

- ^ Qureshi 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Ewald 1994.

- ^ a b Spanish flu strikes during World War I, 14 January 2010

- ^ Barry JM (January 2004). "The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications". Journal of Translational Medicine. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-2-3. PMC 340389. PMID 14733617.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bynum B (14 March 2009). "Stories of an influenza pandemic" (PDF). The Lancet. 373 (9667): 885–886. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60530-4. S2CID 53274511.

- ^ Avian Bird Flu. 1918 Flu (Spanish flu epidemic).

- ^ Channel 4 – News – Spanish flu facts.

- ^ Taubenberger & Morens 2006, pp. 15–22.

- ^ CDC 2009.

- ^ a b c Knobler 2005.

- ^ "Historical Estimates of World Population". Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Potter 2006.

- ^ a b c Barry 2004. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBarry2004 (help)

- ^ Human Extinction Isn't That Unlikely, The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer, April 29, 2016.

- ^ Mayor, S. (2000). "Flu experts warn of need for pandemic plans". British Medical Journal. 321 (7265): 852. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.852. PMC 1118673. PMID 11021855.

- ^ Chandra, Kuljanin & Wray 2012.

- ^ "Spanish Influenza in Japanese Armed Forces, 1918–1920". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ^ Historical research report from University of Indonesia, School of History, as reported in Emmy Fitri. Looking Through Indonesia's History For Answers to Swine Flu Archived 2 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Jakarta Globe. 28 October 2009 edition.

- ^ Kohn 2007.

- ^ Noted. "1918 flu centenary: How to survive a pandemic". Noted. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Rice, Geoffrey. Black November: the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand. Bryder, Linda (Second edition, revised and enlarged ed.). Christchurch, N.Z. ISBN 9781927145913. OCLC 960210402.

- ^ Afkhami 2003; Afkhami 2012.

- ^ The Great Pandemic: The United States in 1918–1919, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ^ "Flu Epidemic Hit Utah Hard in 1918, 1919". Deseret News. 28 March 1995. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "The Great Pandemic of 1918: State by State". 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ "A deadly virus rages throughout Canada at the end of the First World War". CBC History.

- ^ "A gripe espanhola no Brasil – Elísio Augusto de Medeiros e Silva, empresário, escritor e membro da AEILIJ" (in Portuguese). Jornal de Hoje. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "The "bird flu" that killed 40 million". BBC News. 19 October 2005.

- ^ Hays 1998.

- ^ Harold Marcus, Haile Sellassie I: The formative years, 1892–1936 (Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1996), pp. 36f

- ^ Pankhurst 1991, pp. 48f.

- ^ Pankhurst 1991, p. 63.

- ^ Pankhurst 1991, pp. 51ff.

- ^ "Bacterial Pneumonia Caused Most Deaths in 1918 Influenza Pandemic". National Institutes of Health. 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b Taubenberger et al. 2001, pp. 1829–1839.

- ^ a b Simonsen et al. 1998.

- ^ Hanssen, Olav. Undersøkelser over influenzaens optræden specielt i Bergen 1918–1922. Bg. 1923. 66 s. ill. (Haukeland sykehus. Med.avd.Arb. 2) (Klaus Hanssens fond. Skr. 3)

- ^ Payne MS, Bayatibojakhi S (2014). "Exploring preterm birth as a polymicrobial disease: an overview of the uterine microbiome". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 595. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00595. PMC 4245917. PMID 25505898.

- ^ Barry 2004, p. 239. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFBarry2004 (help)

- ^ Key Facts about Swine Influenza [1] accessed 22:45 GMT-6 30 April 2009. Archived 4 May 2009.

- ^ He et al. 2011.

- ^ He et al. 2013.

- ^ UK Parliament – http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.com/pa/ld200506/ldselect/ldsctech/88/88.pdf. Accessed 2009-05-06. Archived 8 May 2009.

- ^ Gladwell 1997, p. 55.

- ^ Gladwell 1997, p. 63.

- ^ Fogarty International Center. "Summer Flu Outbreak of 1918 May Have Provided Partial Protection Against Lethal Fall Pandemic". Fic.nih.gov. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Gladwell 1997, p. 56.

- ^ "Viruses of Mass Destruction", Fortune, 01 November 2004; accessed 30 April 2009

- ^ a b Denoon 2004.

- ^ a b Wishart, Skye (July–August 2018). "How the 1918 flu spread". New Zealand Geographic (152): 23.

- ^ Rice 2005, p. 221.

- ^ Plaspohl SS, Dixon BT, Owen N (2016). ""The Effect of the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic on Mortality Rates in Savannah, Georgia". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 100 (3): 332. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. 31 (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 3401475.

- ^ Cheng, K. F.; Leung, P. C. (1 July 2007). "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11 (4): 360–364. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 17379558.

- ^ Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R.; Krewski, Daniel (6 December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. 31 (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 3401475.

- ^ Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R.; Krewski, Daniel (6 December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. 31 (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. ISSN 1728-4457.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Killingray, David; Phillips, Howard (2 September 2003). The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: New Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56640-2.

- ^ Cheng, K. F.; Leung, P. C. (1 July 2007). "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11 (4): 360–364. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.009. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 17379558.

- ^ World Health Organization Writing Group (2006). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, international measures" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Journal. 12 (1): 189.

- ^ "1919 - Spanish Flu Reports in south-western Victoria, Australia". 17 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 September 2004.

- ^ Spinney 2017. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpinney2017 (help)

- ^ Ryan, Jeffrey, ed. Pandemic influenza: emergency planning and community preparedness. Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2009. P. 24

- ^ "Colonial Annual Report", 1919

- ^ a b Starko 2009.

- ^ a b Noymer, Carreon & Johnson 2010.

- ^ Starko 2010.

- ^ Almond, Douglas (1 August 2006). "Is the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Over? Long‐Term Effects of In Utero Influenza Exposure in the Post‐1940 U.S. Population". Journal of Political Economy. 114 (4): 672–712. doi:10.1086/507154. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 20055129.

- ^ Beach, Brian; Ferrie, Joseph P.; Saavedra, Martin H. (2018). "Fetal Shock or Selection? The 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Human Capital Development".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vilensky, Foley & Gilman 2007.

- ^ Honigsbaum 2008.

- ^ Morrissey 1986.

- ^ Benedict & Braithwaite 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Crosby 2003, pp. 320–322.

- ^ Garrett 2007.

- ^ Lindley, Robin, The Forgotten American Pandemic: Historian Dr. Nancy K. Bristow on the Influenza Epidemic of 1918

- ^ Davis 2013, pp. 103–136.

- ^ "Open Collections Program: Contagion, Spanish Influenza in North America, 1918–191". Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Sometimes a virus contains both avian-adapted genes and human-adapted genes. Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic strains contained avian flu virus RNA segments. "While the pandemic human influenza viruses of 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) clearly arose through reassortment between human and avian viruses, the influenza virus causing the 'Spanish flu' in 1918 appears to be entirely derived from an avian source (Belshe 2005)." (from Chapter Two: Avian Influenza by Timm C. Harder and Ortrud Werner, a free on-line book called Influenza Report 2006)

- ^ Taubenberger et al. 2005.

- ^ Antonovics, Hood & Baker 2006.

- ^ Vana & Westover 2008.

- ^ dos Reis, Hay & Goldstein 2009.

- ^ Center for Disease Control: Researchers Reconstruct 1918 Pandemic Influenza Virus; Effort Designed to Advance Preparedness Retrieved on 2 September 2009

- ^ Kobasa & et al. 2007.

- ^ USA Today: Research on monkeys finds resurrected 1918 flu killed by turning the body against itself Retrieved on 14 August 2008.

- ^ BBC News: Body exhumed in fight against flu Retrieved on 16 September 2008.

- ^ BBC Four documentary. In Search of Spanish Flu

- ^ Fox 2008.

- ^ Fox 2010.

- ^ Crosby 1976, p. 295.

- ^ Madhav 2013.

- ^ Branswell, Helen, A shot-in-the-dark email leads to a century-old family treasure — and hope of cracking a deadly flu’s secret, Stat, December 5, 2018

- ^ See:

- Hammond, J.A.B.; Rolland, William; Shore, T.H.G. (14 July 1917). "Purulent bronchitis: A study of cases occurring amongst the British troops at a base in France". The Lancet. 190 (4898): 41–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)56229-7.

- "The Influenza Pandemic of 1918", World War 1 Centenary, University of Oxford (Oxford, England, UK).

Bibliography

[edit]- Antonovics J, Hood ME, Baker CH (April 2006). "Molecular virology: was the 1918 flu avian in origin?". Nature. 440 (7088): E9, discussion E9–10. Bibcode:2006Natur.440E...9A. doi:10.1038/nature04824. PMID 16641950. S2CID 4382489.

- Afkhami, Amir (2003). "Compromised Constitutions: The Iranian Experience with the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 77 (2): 367–392. doi:10.1353/bhm.2003.0049. PMID 12955964. S2CID 37523219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) – Open access material by the Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Health Sciences Research Commons. - Afkhami, Amir (29 March 2012) [15 December 2004]. "Influenza". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Fasc. 2. Vol. XIII (Online ed.). New York City: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 140–143.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Barry JM (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-89473-4.

- Barry JM (January 2004). "The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications". Journal of Translational Medicine. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-2-3. PMC 340389. PMID 14733617.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Benedict ML, Braithwaite M (2000). "The Year of the Killer Flu". In the Face of Disaster: True Stories of Canadian Heroes from the Archives of Maclean's. New York, N.Y: Viking. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-670-88883-2.

- Billings M (1997). "The 1918 Influenza Pandemic". Virology at Stanford University. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Bristow, Nancy K. American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (OUP, 2012)

- "1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics". Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Chandra S, Kuljanin G, Wray J (August 2012). "Mortality from the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919: the case of India". Demography. 49 (3): 857–65. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0116-x. PMID 22661303. S2CID 39247719.

- Collier R (1974). The Plague of the Spanish Lady – The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19. Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-10592-0.

- Crosby AW (1976). Epidemic and Peace, 1918. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-8376-3.

- Crosby AW (2003). America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54175-6.

- Davis RA (2013). The Spanish Flu: Narrative and Cultural Identity in Spain, 1918. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-33921-8.

- Denoon, Donald (2004). "New Economic Orders: Land, Labour and Dependency". In Denoon, Donald (ed.). The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. CUP. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-521-00354-4.

- dos Reis M, Hay AJ, Goldstein RA (October 2009). "Using non-homogeneous models of nucleotide substitution to identify host shift events: application to the origin of the 1918 'Spanish' influenza pandemic virus". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 69 (4): 333–45. Bibcode:2009JMolE..69..333D. doi:10.1007/s00239-009-9282-x. PMC 2772961. PMID 19787384.

- Ewald PW (1994). Evolution of infectious disease. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-506058-4.

- Fox, Maggie (29 December 2008). "Researchers unlock secrets of 1918 flu pandemic". Reuters. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Fox, Maggie (16 June 2010). "Swine flu shot protects against 1918 flu: study". Reuters.

- Galvin J (31 July 2007). "Spanish Flu Pandemic: 1918". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Garret TA (2007). Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a Modern-day Pandemic (PDF).

- Gladwell M (29 September 1997). "The Dead Zone". New Yorker.

- Hays JN (1998). The Burdens of Disease: Epidemics and Human Response in Western History. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-8135-2528-0.

- He DH, Dushoff J, Day T, Ma J, Earn DJ (2011). "Mechanistic modelling of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Theoretical Ecology. 4 (2): 283–288. doi:10.1007/s12080-011-0123-3. ISSN 1874-1738. S2CID 2010776.

- He D, Dushoff J, Day T, Ma J, Earn DJ (September 2013). "Inferring the causes of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic in England and Wales". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 280 (1766): 20131345. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1345. PMC 3730600. PMID 23843396.

- Honigsbaum M (2008). Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21774-4.

- Humphries, Mark Osborne (2014). "Paths of Infection: The First World War and the Origins of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". War in History. 21 (1): 55–81. doi:10.1177/0968344513504525. S2CID 159563767.

- Johnson NP, Mueller J (2002). "Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 76 (1): 105–15. doi:10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. PMID 11875246. S2CID 22974230.

- Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (eds.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61.

- Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, Kash JC, Copps J, Ebihara H, Hatta Y, Kim JH, Halfmann P, Hatta M, Feldmann F, Alimonti JB, Fernando L, Li Y, Katze MG, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y (January 2007). "Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 445 (7125): 319–23. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..319K. doi:10.1038/nature05495. PMID 17230189. S2CID 4431644.

- Kohn GC (2007). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present (3rd ed.). Infobase Publishing. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8160-6935-4.

- Dorratoltaj, Narges (29 March 2018). Carrell, Heidi (ed.). "What the 1918 Flu Pandemic Can Teach Today's Insurers". AIR Research and Modeling Group. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Morrisey, Carla R. (1986). "The Influenza Epidemic of 1918". Navy Medicine. 77 (3): 11–17.

- Noymer A, Carreon D, Johnson N (April 2010). "Questioning the salicylates and influenza pandemic mortality hypothesis in 1918-1919". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (8): 1203, author reply 1203. doi:10.1086/651472. PMID 20233050.

- Pankhurst R (1991). An Introduction to the Medical History of Ethiopia. Trenton: Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-45-5.

- Patterson KD, Pyle GF (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

- Philips H (2010). "The re-appearing shadow of 1918: trends in the historiography of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 21 (1): 121–34. doi:10.3138/cbmh.21.1.121. PMID 15202430.

- Porras-Gallo M, Davis RA, eds. (2014). "The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: Perspectives from the Iberian Peninsula and the Americas". Rochester Studies in Medical History. Vol. 30. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-496-3.

- Potter CW (October 2001). "A history of influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290. S2CID 26392163.

- Price-Smith AT (2008). Contagion and Chaos. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66203-1.

- Qureshi AI (2016). Ebola Virus Disease: From Origin to Outbreak. Academic Press. ISBN 9780128042427.

- Rice GW (2005). Black November; the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand (2nd ed.). University of Canterbury Press. ISBN 978-1-877257-35-3.

- Spinney L (2017). Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-1-784702-40-3.

- Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K (July 1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 178 (1): 53–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.2581. doi:10.1086/515616. JSTOR 30114117. PMID 9652423.

- Starko KM (November 2009). "Salicylates and pandemic influenza mortality, 1918-1919 pharmacology, pathology, and historic evidence". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 49 (9): 1405–10. doi:10.1086/606060. PMID 19788357. (summary by Infectious Diseases Society of America and ScienceDaily, October 3, 2009)

- Starko, Karen M. (2010). "Reply to Noymer et al" (PDF). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (8): 1203–1204. doi:10.1086/651473.

- Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Fanning TG (December 2001). "Integrating historical, clinical and molecular genetic data in order to explain the origin and virulence of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1416): 1829–39. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1020. PMC 1088558. PMID 11779381.

- Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Lourens RM, Wang R, Jin G, Fanning TG (October 2005). "Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes". Nature. 437 (7060): 889–93. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..889T. doi:10.1038/nature04230. PMID 16208372. S2CID 4405787.

- Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (January 2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711.

- Valentine, Vikki (20 February 2006). "Origins of the 1918 Pandemic: The Case for France". NPR. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Vana G, Westover KM (June 2008). "Origin of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus: a comparative genomic analysis". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 47 (3): 1100–10. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.003. PMID 18353690.

- Vilensky JA, Foley P, Gilman S (August 2007). "Children and encephalitis lethargica: a historical review". Pediatric Neurology. 37 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012. PMID 17675021.

Further reading

[edit]- Beiner G (2006). "Out in the Cold and Back: New-Found Interest in the Great Flu". Cultural and Social History. 3 (4): 496–505.

- Duncan, Kirsty (2003). Hunting the 1918 flu: one scientist's search for a killer virus (illustrated ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8748-5.

- Humphries, Mark Osborne. The Last Plague: Spanish Influenza and the Politics of Public Health in Canada (University of Toronto Press; 29013) examines the public-policy impact of the 1918 epidemic, which killed 50,000 Canadians.

- Johnson N (2006). Britain and the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36560-4.

- Johnson, Niall (2003). "Measuring a pandemic: Mortality, demography and geography". Popolazione e Storia: 31–52.

- Johnson N (2003). "Scottish 'flu – The Scottish mortality experience of the "Spanish flu". Scottish Historical Review. 83 (2): 216–226. doi:10.3366/shr.2004.83.2.216.

- Kolata G (1999). Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-15706-7.

- Little J (2007). If I Die Before I Wake: The Flu Epidemic Diary of Fiona Macgregor, Toronto, Ontario, 1918. Dear Canada. Markham, Ont.: Scholastic Canada. ISBN 978-0-439-98837-7.

- Noymer A, Garenne M (2000). "The 1918 influenza epidemic's effects on sex differentials in mortality in the United States". Population and Development Review. 26 (3): 565–81. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00565.x. PMC 2740912. PMID 19530360.

- Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Innes W, Daniels RS, Johnson NP (February 2002). "World War I may have allowed the emergence of "Spanish" influenza". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 2 (2): 111–4. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00185-8. PMID 11901642.

- Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Johnson NP, Daniels RS (December 1999). "Who's that lady?". Nature Medicine. 5 (12): 1351–2. doi:10.1038/70913. PMID 10581070. S2CID 5065916.

- Pettit D, Janice Bailie (2008). A Cruel Wind: Pandemic Flu in America, 1918–1920. Murfreesboro, TN: Timberlane Books. ISBN 978-0-9715428-2-2.

- Phillips H, Killingray D, eds. (2003). The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918: New Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.

- Rice, Geoffrey W.; Edwina Palmer (1993). "Pandemic Influenza in Japan, 1918–1919: Mortality Patterns and Official Responses". Journal of Japanese Studies. 19 (2): 389–420. doi:10.2307/132645. JSTOR 132645.

- Spinney L (2017). Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-1-784702-40-3.

- Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Mikulasova A, Taubenberger JK, Swayne DE, Palese P, Basler CF (October 2002). "Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (21): 13849–54. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913849T. doi:10.1073/pnas.212519699. PMC 129786. PMID 12368467.

External links

[edit]- We Heard the Bells: The Influenza of 1918 on YouTube

- Nature "Web Focus" on 1918 flu, including new research

- Influenza Pandemic on stanford.edu

- The Great Pandemic: The U.S. in 1918–1919. US Dept. of HHS

- The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1919: A Digital Encyclopedia Largest digital collection of newspapers, archival manuscripts and interpretive essays exploring the impact of the epidemic on 50 U.S. cities (Univ. of Michigan).

- Little evidence for New York City quarantine in 1918 pandemic. 27 Nov 2007 (CIDRAP News)

- Flu by Eileen A. Lynch. The devastating effect of the Spanish flu in the city of Philadelphia, PA, USA

- Dialog: An Interview with Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger on Reconstructing the Spanish Flu

- The Deadly Virus – The Influenza Epidemic of 1918 US National Archives and Records Administration – pictures and records of the time

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand – includes recorded recollections of people who lived through it

- Influenza 1918 "American Experience" PBS.

- An Avian Connection as a Catalyst to the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic

- Fluwiki.com Annotated links to articles, books and scientific research on the 1918 influenza pandemic

- Alaska Science Forum – Permafrost Preserves Clues to Deadly 1918 Flu

- Pathology of Influenza in France, 1920 Report

- Yesterday's News blog 1918 newspaper account on impact of flu on Minneapolis

- "Study uncovers a lethal secret of 1918 influenza virus" University of Wisconsin – Madison, 17 January 2007

- Spanish Influenza in North America, 1918–1919

- 1918 Influenza Virus and memory B-cells – Exposure to virus generates lifelong immune response.

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- Spanish Flu with rare pictures from Otis Historical Archives

- "No Ordinary Flu" a comic book of the 1918 flu pandemic published by Seattle & King County Public Health

- "Closing in on a Killer: Scientists Unlock Clues to the Spanish Influenza Virus" An online exhibit from the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

- Sources for the study of the 1918 influenza pandemic in Sheffield, UK Produced by Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives

- Booknotes interview with Gina Kolata on Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It, 27 February 2000.