User:LakesideMiners/StuffIAmFixing/CCANDN

|

Popes Pius XI (1922–39) and Pius XII (1939–58) led the Roman Catholic Church through the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, generally living in Southern Germany while Protestants dominated the North. The German Catholic church had spoken against the rise of Nazism, but the Catholic aligned Centre Party capitulated in 1933. In the various 1933 elections, the percentage of Catholics voting for the Nazi party was remarkably lower than average.[1] Nazi key ideologue Alfred Rosenberg was banned on the index of the Inquisition, presided by later pope Pius XII. Adolf Hitler and several key Nazis had been raised Catholic, but became hostile to the Church in adulthood. While Article 24 of the NSDAP party platform called for conditional toleration of Christian denominations and the 1933 Reichskonkordat treaty with the Vatican purported to guarantee religious freedom for Catholics, the Nazis were essentially hostile to Catholicism. Catholic press, schools, and youth organizations were closed, property was confiscated, and around one third of Catholic clergy faced reprisals from authorities. Catholic lay leaders were targeted in the Night of the Long Knives purge. The Church hierarchy attempted to cooperate with the new government, but in 1937, the Papal Encyclical Mit brennender Sorge accused the government of "fundamental hostility" to the church.

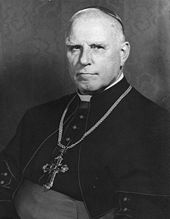

Among the most courageous demonstrations of opposition inside Germany were the 1941 sermons of Bishop August von Galen of Münster. Nevertheless, wrote Alan Bullock "[n]either the Catholic Church nor the Evangelical Church... as institutions, felt it possible to take up an attitude of open opposition to the regime".[2] In every country under German occupation, priests played a major part in rescuing Jews, but Catholic resistance to mistreatment of Jews in Germany was generally limited to fragmented and largely individual efforts. Mary Fulbrook wrote that when politics encroached on the church, Catholics were prepared to resist, but that the record was otherwise patchy and uneven, and that, with notable exceptions, "it seems that, for many Germans, adherence to the Christian faith proved compatible with at least passive acquiescence in, if not active support for, the Nazi dictatorship".[3]

Catholics fought on both sides in the Second World War. Hitler's invasion of predominantly Catholic Poland ignited the conflict in 1939. Here, especially in the areas of Poland annexed to the Reich—as in other annexed regions of Slovenia and Austria—Nazi persecution of the church was intense. Many clergy were targeted for extermination. Through his links to the German Resistance, Pope Pius XII warned the Allies of the planned Nazi invasion of the Low Countries in 1940. From that year, the Nazis gathered priest-dissidents in a dedicated clergy barracks at Dachau, where 95 percent of its 2,720 inmates were Catholic (mostly Poles, with 411 Germans). 1,034 priests died there. Expropriation of church properties surged from 1941.

The Vatican, surrounded by Fascist Italy, was officially neutral during the war, but used diplomacy to aid victims and lobby for peace. Vatican Radio and other Catholic media spoke out against atrocities.

While Nazi antisemitism embraced modern pseudo-scientific racial principles, ancient antipathies between Christianity and Judaism contributed to European anti-Semitism. Despite this, the Church rescued many thousands of Jews by issuing false documents, lobbying Axis officials, and hiding Jews in monasteries, convents, schools and elsewhere; including in the Vatican and papal residence at Castel Gandolfo. The Pope's role during this period is contested. The Reich Security Main Office called Pius XII a "mouthpiece" of the Jews. His first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, called the invasion of Poland an "hour of darkness." His 1942 Christmas address denounced race murders and his Mystici corporis Christi encyclical (1943) denounced the murder of the handicapped.[4]

Overview

[edit]In the 1930s, Catholics constituted a third of the population of Germany. "Political Catholicism" was a major force in the interwar Weimar Republic. Prior to 1933, Catholic leaders denounced Nazi doctrines while Catholic regions generally did not vote Nazi. Though hostility between the Nazi Party and the Catholic Church was real, the Nazi Party first developed in largely Catholic Munich, where many Catholics, lay and clerical, offered enthusiastic support.[5] This early affinity lessened after 1923. By 1925, Nazism had embarked on a different path following its reconstitution in 1920, taking a decidedly anti-Catholic identity.[6] In early 1931, the German Bishops issued an edict excommunicating all Nazi leadership and banned Catholics from membership. The ban was conditionally modified in the spring of 1933 under pressure to address State law requiring all Civil Servants and Trade Union workers to be members of the Nazi Party, while retaining condemnation of core Nazi ideology.[7] In early 1933, following Nazi successes in the 1932 elections, lay Catholic monarchist Franz von Papen and acting Chancellor and Presidential advisor, General Kurt von Schleicher, assisted Adolf Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg. In March, amidst the intimidating atmosphere of Nazi terror tactics and negotiation[8] following the Reichstag Fire Decree,[9] the lay Catholic Centre Party led by prelate Ludwig Kaas (on the condition of a written commitment that the President's veto power be retained[10]) the allied BNVP and the monarchist DNVP voted for the Enabling Act. The Center Party's attitude had become crucial since the act could not be passed by the Nazi and DNVP coalition alone. It marked the transition in Adolf Hitler's reign from democratic to dictatorial power.[11] By June 1933 the only institutions not under Nazi domination were the military and the churches.[12] The Reichskonkordat treaty of July 1933, signed between Germany and the Holy See, pledged to respect the autonomy of the Catholic Church but required clerics to refrain from politics. Hitler welcomed the treaty, though he routinely violated it in the Nazi struggle with the churches.[13] When president Hindenberg died in August 1934, the Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all levels of government and a referendum confirmed Hitler as sole Führer (leader) of Germany. A Nazi program known as Gleichschaltung sought control of all collective and social activity and interfered with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers, and cultural groups. The church insisted on its loyalty to the nation, but resisted regimentation and oppression of church organizations and contraventions of doctrine such as the sterilization law of 1933.

Hitler's ideologues Goebbels, Himmler, Rosenberg and Bormann hoped to de-Christianize Germany, or at least distort its theology to their point of view.[14][15] The government moved to close all Catholic institutions which were not strictly religious. Catholic schools were shut by 1939, the Catholic press by 1941.[16][17] Clergy, religious women and men, and lay leaders were targeted. During the course of Hitler's rule, thousands were arrested, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[18] Germany's senior cleric, Cardinal Bertram, developed an ineffectual protest system, leaving broader Catholic resistance to individual conscience. By 1937 the church hierarchy, which initially sought dètente, was highly disillusioned. Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical. It condemned racism, accused the Nazis of violations of the Concordat and "fundamental hostility" to the church.[18] The state responded by renewing its crackdown and propaganda against Catholics.[16] Despite violence against Catholic Poland, some German priests offered prayers for the German cause at the outbreak of war. Nevertheless, security chief Reinhard Heydrich soon orchestrated an intensification of restrictions on church activities. Expropriation of monasteries, convents and church properties surged from 1941. Bishop Clemens von Galens's ensuing 1941 denunciation of Nazi euthanasia and defence of human rights roused rare popular dissent. The German bishops denounced Nazi policy towards the church in pastoral letters, calling it "unjust oppression".[19][20]

Pius XII, former nuncio to Germany, became Pope on the eve of war. His legacy is contested. As Vatican Secretary of State, he advocated Détente via the Reich Concordat, hoping it would build trust and respect within Hitler's government, and assisted in drafting the anti-Nazi Mit brennender Sorge. His first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, called the invasion of Poland an "hour of darkness". He affirmed the policy of Vatican neutrality, but maintained links to the German Resistance. Controversy surrounding his reluctance to speak publicly in explicit terms about Nazi crimes continues.[21] He used diplomacy to aid war victims, lobbied for peace, shared intelligence with the Allies, and employed Vatican Radio and other media to speak out against atrocities like race murders. In Mystici corporis Christi (1943) he denounced the murder of the handicapped. A denunciation from German bishops of the murder of the "innocent and defenceless", including "people of a foreign race or descent", followed.[22] While Nazi antisemitism embraced modern pseudo-scientific racial principles, ancient antipathies between Christianity and Judaism contributed to European antisemitism. Under Pius XII, the church rescued many thousands of Jews by issuing false documents, lobbying Axis officials, hiding them in monasteries, convents, schools and elsewhere; including the Vatican and Castel Gandolfo.

In regions of Poland, Slovenia and Austria annexed by Nazi Germany, Nazi persecution of the Church was at its harshest. In Germany and its conquests, Catholic responses to Nazism varied. The papal nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, was timid in protesting Nazi crimes and had sympathies with Italian Fascism. German priests in general were closely watched and often denounced, imprisoned or executed, such as German priest-philosopher, Alfred Delp. From 1940, the Nazis gathered priest-dissidents in dedicated clergy barracks at Dachau, where 95 percent of its 2,720 inmates were Catholic (mostly Poles, and 411 Germans) and 1034 died there. In Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, the Nazis attempted to eradicate the church and over 1800 Polish Catholic clergy died in concentration camps; most notably, Saint Maximilian Kolbe. Influential members of the German Resistance included Jesuits of the Kreisau Circle and laymen such as July plotters Klaus von Stauffenberg, Jakob Kaiser and Bernhard Letterhaus, whose faith inspired resistance.[23] Elsewhere, vigorous resistance from bishops such as Johannes de Jong and Jules-Géraud Saliège, papal diplomats such as Angelo Rotta, and nuns such as Margit Slachta, can be contrasted with the apathy of others and the outright collaboration of Catholic politicians such as Slovakia's Msgr Jozef Tiso and fanatical Croat nationalists. From within the Vatican, Msgr Hugh O'Flaherty coordinated the rescue of thousands of Allied POWs, and civilians, including Jews. A rogue Austrian bishop, Alois Hudal, of the college for German priests in Rome, was an informant for Nazi intelligence. After the war, he and Msgr Krunoslav Draganovic of the Croatian College assisted the so-called "ratlines" facilitating fugitive Nazis to flee Europe.

Background

[edit]Church background

[edit]Roman Catholicism in Germany dates back to the missionary work of Columbanus and St. Boniface in the 6th–8th centuries, but by the 20th century, Catholics were a minority. The Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517, divided German Christians between Protestantism and Catholicism. The south and west remained mainly Catholic, while north and east became mainly Protestant.[24] Bismarck's Kulturkampf ("Battle for Culture") of 1871–78 saw an attempt to assert a Protestant vision of nationalism over the new German Empire, and fused anticlericalism and suspicion of the Catholic population, whose loyalty was presumed to lie with Austria and France. The Catholic Centre Party had formed in 1870, initially to represent the religious interests of Catholics and Protestants, but was transformed by the Kulturkampf into the "political voice of Catholics".[25] By the late 1870s, it was clear that the Kulturkampf was largely a failure, and many of its edicts were undone.[26]

The Catholic Church enjoyed a degree of privilege in the Bavarian region, the Rhineland and Westphalia as well as parts of the south-west, while in the Protestant North, Catholics suffered some discrimination. In the 1930s, the episcopate of the Catholic Church of Germany comprised six archbishops and 19 bishops while German Catholics comprised around one-third of the population, served by 20,000 priests.[27] The revolution of 1918 and the Weimar Constitution of 1919 had thoroughly reformed the former relationship between state and churches.[26] By law, Germany's Protestant and Catholic churches received tax-supported subsidies based on church census data, therefore, were dependent on state support, causing them to be vulnerable to government influence and the political atmosphere of Germany.[26]

Political Catholicism in Germany

[edit]

The Catholic Centre Party (Zentrum) was a social and political force in predominantly Protestant Germany. It assisted the framing of the Weimar constitution at the end of World War I and participated in various Coalition governments of the Weimar Republic (1919–33/34).[28] It aligned with both Social Democrats and the leftist German Democratic Party, while maintaining the centre ground against the rise of extremist parties both left and right.[26][29] Historically, the Centre Party had the strength to defy Bismarck's Kulturkampf and was a bulwark of the Republic. Yet, according to Bullock, from summer 1932, the Party became "notoriously a Party whose first concern was to make accommodation with any government in power in order to secure the protection of its particular interests".[30][31] It remained relatively moderate during the radicalisation of German politics with the onset of the Great Depression, but party deputies voted—with most other parties—for the Enabling Act of March 1933, offering Hitler plenary powers.[28]

In the 1920s and 1930s, Catholic leaders made a number of forthright attacks on Nazi ideology, and the main Christian opposition to Nazism in Germany arose from the Catholic Church.[26] Prior to Hitler's rise, German bishops warned Catholics against Nazi racism. Some dioceses banned membership in the Nazi Party.[32] and Catholic press condemned Nazism.[32] John Cornwell wrote of the early Nazi period that:

Into the early 1930s the German Centre Party, the German Catholic bishops, and the Catholic media had been mainly solid in their rejection of National Socialism. They denied Nazis the sacraments and church burials, and Catholic journalists excoriated National Socialism daily in Germany's 400 Catholic newspapers. The hierarchy instructed priests to combat National Socialism at a local level whenever it attacked Christianity.[33]

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber was appalled by the totalitarianism, neopaganism, and racism of the Nazi movement and, as Archbishop of Munich and Freising, contributed to the failure of the Nazi Munich Putsch of 1923.[34] In early 1931, the Cologne Bishops Conference condemned National Socialism, followed by the bishops of Paderborn and Freiburg. With ongoing hostility toward the Nazis by Catholic press and Centre Party, few Catholics voted Nazi in elections preceding the Nazi takeover in 1933.[35] As in other German churches, there were some clergy and laypeople who openly supported the Nazi administration.[29]

Five Centre Party politicians served as Chancellor of Weimar Germany: Konstantin Fehrenbach, Joseph Wirth, Wilhelm Marx, Heinrich Brüning, and Franz von Papen.[28] With Germany facing the Great Depression, Brüning was appointed chancellor by Hindenburg and was foreign minister shortly before Hitler came to power. Brüning was appointed to form a new, more conservative ministry on March 28, 1930, but did not have a Reichstag majority. On July 16, unable to have key points of his agenda pass parliament, Brüning used Article 48 of the Constitution governing by presidential emergency decree and dissolving the Reichstag on 18 July. New elections were set for September, in which, the Communist and Nazi representation greatly increased, hastening Germany's drift toward rightist dictatorship. Brüning backed Hindenberg over Hitler in the 1932 presidential election, but lost Hindenberg's support as Chancellor. He resigned in May of that year.[36] According to Ventresca, Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli was always nervous of Brüning's reliance on Social Democrats for political survival. A sentiment shared by Ludwig Kaas and many German Catholics. Ventresca wrote that Brüning never forgave Pacelli for what he saw as a betrayal of Catholic political tradition and his leadership.[37]

- Catholic opposition to Communism

Karl Marx's writings against religion pitted Communist movements against the Catholic Church. The church denounced Communism in May 1891 with Leo XIII's encyclical Rerum novarum. The church feared Communist conquest or revolution in Europe. German Christians were alarmed by the spread of militant Marxist‒Leninist atheism, which took hold in Russia following the 1917 Revolution and involved a systematic effort to eradicate Christianity.[38] Seminaries were closed and teaching the faith to the young was criminalized. In 1922, the Bolsheviks arrested the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.[38]

In 1919, Communists, initially led by the moderate Kurt Eisner, briefly attained power in Bavaria. The revolt was seized by the radical Eugen Leviné by force to establish the Bavarian Socialist Republic. This drew reaction across Germany to Bavaria from the right; ranging, moderate to radical. This brief but violent experiment in Munich radicalized anti-Marxist and anti-Semitic sentiment among some in Munich's largely Catholic population. In this atmosphere, the Nazi movement first emerged.[39] Hitler and the Nazis were able to garner some modicum of support. Some German Christians thought he would be a bulwark against Communism.[38] While serving as Apostolic Nuncio to Bavaria, Eugenio Pacelli (later Pius XII) was in Munich during the Spartacist Uprising of 1919, which saw Communists burst into his residence brandishing guns—an experience which contributed to Pacelli's lifelong distrust of Communism.[40] According to historian Derek Hastings many Catholics felt threatened by the possibilities of radical socialism driven, they perceived, by a cabal of Jews and atheists.[41] Robert Ventresca wrote, "After witnessing the turmoil in Munich, Pacelli reserved his harshest criticism for Kurt Eisner." Pacelli saw Eisner as an atheist, radical Socialist, with ties to Russian nihilists as embodying the revolution in Bavaria; "What is more, Pacelli told his superiors, Eisner was a Galician Jew. A threat to Bavaria's religious, political, and social life".[42] The Catholic priest Anton Braun, in a well-publicized sermon in December 1918, called Eisner a sleazy Jew and his administration a pack of unbelieving Jews.[41] Pius XI saw the rising tide of Totalitarianism in Europe with alarm. He delivered papal encyclicals challenging the new creeds, including Divini redemptoris ("Divine Redeemer") against atheistic Communism in 1937.[43]

Nazi views on Catholicism

[edit]

Nazi ideology could not accept an autonomous establishment whose legitimacy did not spring from the government. It desired the subordination of the church to the state.[44] While the Article 24 of the NSDAP party platform called for conditional toleration of Christian denominations and a Reichskonkordat (Reich Concordat) treaty with the Vatican was signed in 1933, purporting to guarantee religious freedom for Catholics, Hitler believed religion was fundamentally incompatible with National Socialism."[45][incomplete short citation][46] Out of political expediency, the dictator intended to postpone the elimination of the Christian churches until after the war.[47][incomplete short citation] However, his repeated hostile statements against the church indicated to his subordinates that continuation of the Kirchenkampf (church struggle) would be tolerated and even encouraged.[48]

Many Nazis suspected Catholics of insufficient patriotism, or even of disloyalty to the Fatherland, and of serving the interests of "sinister alien forces".[49] Shirer wrote that "under the leadership of Rosenberg, Bormann and Himmler—backed by Hitler—the Nazi regime intended to destroy Christianity in Germany, if it could, and substitute the old paganism of the early tribal Germanic gods and the new paganism of the Nazi extremists."[50] Anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.[51]

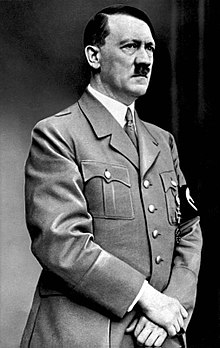

Hitler

[edit]Raised a Catholic, Hitler retained some regard for the organisational power of the Catholic church, but had utter contempt for its central teachings which, he said, if taken to their conclusion "would mean the systematic cultivation of the human failure".[52] Hitler was aware Bismarck's kulturkampf of the 1870s was defeated by the unity of Catholics behind the Centre Party and was convinced Nazism could only succeed if Political Catholicism, and its democratic networks, were eliminated.[33][53][54] Important conservative elements, such as the officer corps, opposed Nazi persecution of the churches.[55][56]

Because of such political considerations, Hitler occasionally spoke of wanting to delay the church struggle and was prepared to restrain his anticlericalism. But, his own inflammatory remarks to his inner circle encouraged underlings to continue their battle with the churches.[51] He declared that science would destroy the last vestiges of superstition and that, in the long run, Nazism and religion could not co-exist. Germany couldn't tolerate intervention of foreign influences like the Vatican; and priests, he said, were "black bugs" and "abortions in black cassocks".[57]

In Hitler's eyes, Christianity was a religion fit only for slaves; he detested its ethics in particular. Its teaching, he declared, was a rebellion against the natural law of selection by struggle and the survival of the fittest.

— Extract from Hitler: a Study in Tyranny, by Alan Bullock

- Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda, was among the most aggressive anti-Church radicals and saw the conflict with the churches as a priority concern.[51] Born to a Catholic family, he became one of the government's most relentless Jew-baiters.[58] On the "Church Question", he wrote "after the war it has to be generally solved .... There is, namely, an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view".[51] He led the persecution of Catholic clergy.[51]

- Himmler and Heydrich

Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich headed the Nazi security forces and were key architects of the Final Solution. Both believed Christian values were among the enemies of Nazism: the enemies were "eternally the same", wrote Heydrich: "the Jew, the Freemason, and the politically-oriented cleric." Modes of thinking like Christian and liberal individualism he considered the residue of inherited racial characteristics, biologically sourced to Jewry—who must, therefore, be exterminated.[59] According to Himmler biographer Peter Longerich, Himmler was vehemently opposed to Christian sexual morality and the "principle of Christian mercy", both of which he saw as a dangerous obstacle to his plans to battle with "subhumans".[60] In 1937 he wrote:[61]

We live in an era of the ultimate conflict with Christianity. It is part of the mission of the SS to give the German people in the next half-century the non-Christian ideological foundations on which to lead and shape their lives. This task does not consist solely in overcoming an ideological opponent but must be accompanied at every step by a positive impetus: in this case, that means the reconstruction of the German heritage in the widest and most comprehensive sense.

— Heinrich Himmler, 1937

Himmler saw the main task of his Schutzstaffel (SS) organisation to be that of "acting as the vanguard in overcoming Christianity and restoring a 'Germanic' way of living" in order to prepare for the coming conflict between "humans and subhumans":[60] Longerich wrote that, while the Nazi movement as a whole launched itself against Jews and Communists, "by linking de-Christianisation with re-Germanization, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and purpose all of its own."[60] He set about making his SS the focus of a "cult of the Teutons".[62]

- Bormann

Hitler's chosen deputy and private secretary from 1941, Martin Bormann, was a militant anti-Church radical.[51] He had a particular loathing for the Semitic origins of Christianity.[63] He was one of the leading proponents of the ongoing persecution of the Christian churches.[64][incomplete short citation] When the Bishop of Munster led the public protest against Nazi euthanasia, Bormann called for him to be hanged.[65] Strongly anti-Christian, he stated publicly in 1941 that "National Socialism and Christianity are irreconcilable."[50]

- Rosenberg

In January 1934, Hitler appointed Alfred Rosenberg the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Rosenberg was a neo-pagan and notoriously anti-Catholic.[50][67] Rosenberg was initially the editor of the young Nazi Party's newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter.[68] In 1924, Hitler chose Rosenberg to oversee the Nazi movement while he was in prison (this may have been because he was unsuitable for the task and unlikely to emerge a rival).[69] In "Myth of the Twentieth Century" (1930), Rosenberg described the Catholic Church as one of the main enemies of Nazism.[70] Rosenberg proposed to replace traditional Christianity with the neo-pagan "myth of the blood":[71] He wrote: "We now realize that the central supreme values of the Roman and the Protestant Churches [-] hinder the organic powers of the peoples determined by their Nordic race, [-] they will have to be remodelled " in The Myth of the 20th Century in 1930.

Church officials were perturbed by Hitler's appointment of Rosenberg as the state's official philosopher. The indication being, Hitler was endorsing his anti-Jewish, anti-Christian, and neo-pagan philosophy. The Vatican directed the Holy Office to place Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century on the Index of Forbidden books on February 7, 1934.[72] Joachim Fest wrote of Rosenberg having little, or no, political influence in making government decisions, and thoroughly marginalized.[73] Hitler called his book "derivative, pastiche, illogical rubbish!"[74]

- Kerrl

Following the failure of the pro-Nazi Ludwig Müller to unite Protestants behind the Nazi Party in 1933, Hitler appointed his friend Hans Kerrl Minister for Church Affairs in 1935. A relative moderate among Nazis, Kerrl confirmed Nazi hostility to the Catholic and Protestant creeds in a 1937 address during an intense phase of the Nazi Kirchenkampf:[75]

The Party stands on the basis of Positive Christianity, and positive Christianity is National Socialism... National Socialism is the doing of God's will... God's will reveals itself in German blood;... Dr Zoellner and Count Galen have tried to make clear to me that Christianity consists in faith in Christ as the son of God. That makes me laugh... No, Christianity is not dependent upon the Apostle's Creed... True Christianity is represented by the party, and the German people are now called by the party and especially the Fuehrer to a real Christianity... the Fuehrer is the herald of a new revelation.

— Hans Kerrl, Nazi Minister for Church Affairs, 1937

Catholicism in Nazi Germany

[edit]Nazis take power

[edit]After World War I, Hitler became involved with the fledgling Nazi Party. He set the violent tone of the movement early, forming the Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary.[76] Catholic Bavaria resented rule from Protestant Berlin, and Hitler initially saw the revolution in Bavaria as a means to power, but an early attempt proved fruitless. He was imprisoned after the 1923 Munich Beerhall Putsch. He used the time to produce Mein Kampf, in which he claimed that an effeminate Jewish-Christian ethic was enfeebling Europe, and Germany needed a man of iron to restore itself to build an empire.[77] He decided on the tactic of pursuing power through "legal" means.[78]

Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Nazis and Communists made great gains at the 1930 Election. Greatest gains for the Nazis came in the Protestant, rural towns of the North, while Catholic areas remained loyal to the Centre Party.[79] Both Nazis and Communists pledged to eliminate democracy; between them, they secured over 50 percent of Reichstag seats.[80] Germany's political system made it difficult for chancellors to govern with a stable parliamentary majority. Successive chancellors instead relied on the president's emergency powers to govern.[81] From 1931–33, Nazis combined terror tactics with conventional campaigning. Hitler criss-crossed the nation by air, while SA troops paraded in the streets, beat up opponents, and broke up their meetings.[78] A middle class liberal party strong enough to block the Nazis did not exist: the Social Democrats were essentially a conservative trade union party, with ineffectual leadership; the Centre Party maintained its voting block, but was preoccupied defending its own particular interests; and the Communists, meanwhile, were engaging in violent clashes with Nazis on the streets. Moscow had directed the Communist Party to prioritise destruction of the Social Democrats, seeing more danger in them as a rival. But it was the German Right who made Hitler their partner in a coalition government.[82]

This coalition did not come about immediately: the Centre Party's Heinrich Brüning, Chancellor from 1930–32, was unable to reach terms with Hitler, and increasingly governed with the support of the President and Army over that of the parliament.[83] With the backing of Kurt von Schleicher and Hitler's stated approval, the 84-year-old President von Hindenberg, a conservative monarchist, appointed the Catholic monarchist Franz von Papen to replace Brüning as Chancellor in June 1932.[84][85] Papen was active in the resurgence of the Harzburg Front,[86] and had fallen out with the Centre Party.[87] He hoped, ultimately, to outmaneuver Hitler.[88]

At the July 1932 elections, the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag. Hitler withdrew his support for Papen and demanded the chancellorship. Hindenberg refused. In return, the Nazis approached the Centre Party to sound out a coalition but no agreement was reached.[89] Papen dissolved Parliament, and the Nazi vote declined in the November Election.[90] Hindenberg appointed Schleicher as chancellor,[91] whereupon the aggrieved Papen opened negotiations with Hitler, and came to an agreement.[92] Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor on January 30, 1933, in a coalition arrangement between the Nazis and the Nationalist-Conservatives. Papen was to serve as Vice-Chancellor in a majority conservative Cabinets, falsely believing he could "tame" Hitler.[85] Initially, Papen did speak out against some Nazi excesses and only narrowly escaped death in the Night of the Long Knives, where after he ceased to openly criticize the Hitler government. German Catholics met the Nazi takeover with apprehension, as leading clergy had been warning against Nazism for years.[93] A threatening though at first sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany commenced.[94]

Enabling Law

[edit]

Following the Reichstag fire, the Nazis began to suspend civil liberties and eliminate political opposition, excluding the Communists from the Reichstag. At the March 1933 elections, again no single party secured a majority. Hitler required the Reichstag votes of the Centre Party and Conservatives. He told the Reichstag on March 23 that Positive Christianity was the "unshakeable foundation of the moral and ethical life of our people", and promised not to threaten the churches or the institutions of the Republic if granted plenary powers.[95] Employing a characteristic mix of negotiation and intimidation, the Nazis called on the Centre Party, led by Ludwig Kaas, and all other parties in the Reichstag, to vote for the Enabling Act on 24 March 1933.[96] The law was to give Hitler the freedom to act without parliamentary consent or constitutional limitations.[97]

Hitler offered the possibility of friendly co-operation, promising not to threaten the Reichstag, the President, the states, or the churches if granted emergency powers. With Nazi paramilitary encircling the building, he said: "It is for you, gentlemen of the Reichstag to decide between war and peace".[96] Hitler offered Kaas oral guarantees of the Centre Party's continued existence, autonomy of the Church, her educational and cultural institutions. Kaas was aware of the doubtful nature of such guarantees, but told members to support the bill, given the "precarious state of the party". A number opposed the chairman's course, among them former Chancellors Brüning and Joseph Wirth and former minister Adam Stegerwald. Brüning called the Act "the most monstrous resolution ever demanded of a parliament", and was sceptical about Kaas' efforts.[citation needed] The Centre Party, having obtained promises of non-interference in religion, joined with conservatives in voting for the Act (only the Social Democrats voted against).[31] Hoffman wrote that the Centre Party and Bavarian People's Party, along with other groups between the Nazis and the Social-Democrats "voted for their own emasculation in the paradoxical hope of saving their existence thereby".[97] Hitler immediately set about abolishing the powers of the states, the existence of non-Nazi political parties and organisations.[98] The Act, allowed Hitler and his Cabinet to rule by emergency decree for four years, though Hindenberg remained President.[99] The Act did not infringe upon the powers of the President, and Hitler would not fully achieve full dictatorial power until after the death of Hindenburg in August 1934. Hindenburg remained Commander and Chief of the military and retained the power to negotiate foreign treaties. On 28 March the German Bishops' Conference conditionally revised prohibition of Nazi Party membership.[100][101]

Through the winter/spring of 1933 Hitler ordered the wholesale dismissal of Catholic civil servants,[102] The leader of the Catholic Trade Unions was beaten by Brownshirts and a Catholic politician sought protection after S.A. troopers wounded a number of followers at a rally.[103] In this threatening atmosphere, Hitler called for a reorganization of church and state relations of both Catholic and Protestant churches. By June, thousands of Centre Party members were incarcerated in concentration camps. Two thousand functionaries of the Bavarian People's Party were rounded up by police in late June 1933; along with the Centre Party it ceased to exist by early July.[104][105] Lacking public ecclesial support, the Center Party voluntary dissolved on July 5.[106] Non-Nazi parties were formally outlawed on 14 July, and the Reichstag abdicated its democratic responsibilities.[98]

Reichskonkordat

[edit]

Diplomatic policy under Pius XI saw the Catholic Church conclude eighteen concordats, starting in the 1920s. The aim of the church was to safeguard its institutional rights. Historians note the treaties were unsuccessful since, "Europe was entering a period in which such agreements were regarded as mere scraps of paper".[107] The Reich concordat (Reichskonkordat) was signed on July 20, 1933 and ratified in September of that year. The treaty remains in force to the present day.[108][109] It was an extension of existing concordats with Prussia and Bavaria, first realized via the diplomacy of nuncio Eugenio Pacelli with a state level concordat with Bavaria (1924).[108] Peter Hebblethwaite wrote, it was "more like a surrender than anything else: it involved the suicide of the Centre Party ...".[107] Signed by President Hindenburg and Vice Chancellor Papen, it was a realization of a long-standing program of the Catholic Church to secure a nationwide Concordat, dating back to the first year of the Weimar Republic. Breaches of the treaty by the state commenced almost immediately. The church continually protested throughout the Nazi era and preserved diplomatic ties with the Government of Nazi Germany.

Between 1930–33, the church initiated negotiations with successive German governments with limited success while a federal treaty proved elusive.[110] Catholic politicians of the Centre Party repeatedly pushed for a concordat with the German Republic.[111] In February 1930, Pacelli became the Vatican's Secretary of State responsible for the Church's global foreign policy. In this position, he continued to work towards the 'great goal' of securing a treaty with Germany.[110][112] Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazis against the Church and its organisations".[113] Biographer of Pius XII, Robert Ventresca, wrote, "because of increasing harassment of Catholics and Catholic clergy, Pacelli sought a quick ratification of a treaty, seeking, in this way, to protect the German Church." When Vice-Chancellor Papen and Ambassador Diego von Bergen met Pacelli in late June 1933, they found him "visibly influenced" by reports of actions being taken against German Catholic interests.[114] Hitler wanted to end all Catholic political life. The church wanted protection of its schools and organisations, recognition of canon law regarding marriage and the right of the Pope to select bishops.[115] The non-Nazi Vice Chancellor Papen was chosen by the new government to negotiate with the Vatican.[105] The bishops announced on April 6 negotiations toward a concordat would begin in Rome.[116] On April 10, Francis Stratmann O.P., a chaplain to students in Berlin, wrote to Cardinal Faulhaber, "The souls of the well-intentioned are deflated by the National Socialist seizure of power—the bishops' authority is weakened among countless Catholics and non-Catholics because of their quasi-approbation of the National Socialist movement." Some Catholic critics of the Nazis soon chose to emigrate. Among them, Waldemar Gurian, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and Hans A. Reinhold.[117] Hitler began enacting laws restricting movement of funds (making it impossible for German Catholics to send money to missionaries), restricting religious institutions, education, and mandating attendance at Hitler Youth functions (held on Sunday mornings).

On April 8 Vice Chancellor Von Papen, went to Rome. On behalf of Cardinal Pacelli, Ludwig Kaas, the out-going chairman of the Centre Party, negotiated a draft with Papen. Kaas arrived in Rome shortly before Papen because of his expertise in church-state relations. He was authorized by Cardinal Pacelli to negotiate terms with Papen, but pressure by the German government forced him to withdraw from visibly participating.[citation needed] The concordat prolonged Kaas' stay in Rome, leaving the party without a chairman. On 5 May Kaas resigned his post. In his place, the party elected Heinrich Brüning. Congruently, the Centre party was subjected to increasing pressure under the Nazi campaign of Gleichschaltung. The bishops saw a draft May 30, 1933 as they assembled for a joint meeting of the Fulda bishops conference, led by Breslau's Cardinal Bertram. And, the Bavarian bishops' conference, led by its president, Munich's Michael von Faulhaber. Bishop's Wilhelm Berning of Osnabrück, and Archbishop Conrad Grober of Freiburg presented the document to the bishops.[118] Weeks of escalating anti-Catholic violence preceded the conference. Many Catholic bishops feared for the safety of the church if Hitler's demands were not met.[119] The strongest critics of the concordat were Cologne's Cardinal Karl Schulte and Eichstätt's Bishop Konrad von Preysing. They pointed out the Enabling Act established a quasi dictatorship, while the church lacked legal recourse if Hitler decided to disregard the concordat.[118] The bishops approved the draft and delegated Grober, a friend of Cardinal Pacelli and Msgr. Kaas, to present the episcopacy's concerns to Pacelli and Kaas. On June 3, the bishops issued a statement, drafted by Grober, that announced their support for the concordat.[citation needed] After all the other parties had dissolved, or banned by the NSDAP, the Centre Party dissolved itself on 6 July.

On 14 July 1933, the Weimar government accepted the Reichskonkordat. It was signed by Pacelli for the Vatican and von Papen for Germany, 20 July; subsequently, President Hindenburg signed, and it was ratified in September. Article 16 required bishops to make an oath of loyalty to the state. Article 31 acknowledged while the church would continue to sponsor charitable organisations, it would not support political organisations or political causes. Article 31 was supposed to be supplemented by a list of protected catholic agencies, but this list was never agreed upon. Article 32 gave Hitler what he was seeking: exclusion of clergy and members of religious orders from politics. Yet, it was a gratuitous, according to Guenter Lewy's interpretation. In theory, Lewy reasons, members of the clergy could join or remain in the NSDAP without transgressing church discipline. "An ordinance of the Holy See forbidding priests to be members of a political party was never issued." states Lewy. The Nazis state allowed such membership reasoning, "the movement sustaining the state cannot be equated with the political parties of the parliamentary multi-party state in the sense of Article 32.",[120][121] The day after, the government issued a law banning the founding of new political parties, thus turning Germany into a one party state.

Effects of the concordat

Most historians state it offered international acceptance of Adolf Hitler's government.[122] Guenter Lewy, political scientist and author of The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, wrote:

There is general agreement that the Concordat increased substantially the prestige of Hitler's regime around the world. As Cardinal Faulhaber put it in a sermon delivered in 1937: "At a time when the heads of the major nations in the world faced the new Germany with cool reserve and considerable suspicion, the Catholic Church, the greatest moral power on earth, through the Concordat expressed its confidence in the new German government. This was a deed of immeasurable significance for the reputation of the new government abroad."

Historian Robert Ventresca wrote that the Reichskonkordat left German Catholics with no "meaningful electoral opposition to the Nazis", while the "benefits and vaunted diplomatic entente [of the Reichskonkordat] with the German state were neither clear nor certain".[106] In a two-page article in the L'Osservatore Romano on 26 July and 27 July, Cardinal Pacelli said that the purpose of the Reichskonkordat was: "not only the official recognition (by the Reich) of the legislation of the Church (its Code of Canon Law), but the adoption of many provisions of this legislation and the protection of all Church legislation."[citation needed] Cardinal Faulhaber is reported to have said: "With the concordat we are hanged, without the concordat we are hanged, drawn and quartered."[citation needed] According to Paul O'Shea, Hitler had a "blatant disregard" for the Concordat, and its signing was to him merely a first step in the "gradual suppression of the Catholic Church in Germany".[123] In 1942, Hitler stated he viewed the Concordat as obsolete, and intended to abolish it after the war, and only hesitated to withdraw Germany's representative from the Vatican for "military reasons connected with the war": At the war's end we will put a swift end to the Concordat.[124] When Nazi violations of the Reichskonkordat escalated to include physical violence, Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge,[125][126]

Persecution of German Catholics

[edit]A threatening, initially sporadic, persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the Nazi takeover.[94] The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity, interfering with Catholic schooling, youth groups, workers' clubs and cultural societies.[17] "By the latter part of the decade of the Thirties", wrote Phayer, "church officials were well aware that the ultimate aim of Hitler and other Nazis was the total elimination of Catholicism and of the Christian religion. Since the vast majority of Germans were either Catholic or Protestant this goal was a long-term rather than short-term Nazi objective".[127] Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism. The Nazis arrested thousands of members of the German Centre Party.[32] The Catholic Bavarian People's Party government had been overthrown in Bavaria by a Nazi coup on 9 March 1933.[30] Two thousand functionaries of the Party were rounded up by police in late June. The national Centre Party, dissolved themselves in early July. The dissolution of the Centre Party left modern Germany without a Catholic Party for the first time[30] and the Reich Concordat prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[105] Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".[113] Hitler had a "blatant disregard" for the Concordat, wrote Paul O'Shea, and its signing was to him merely a first step in the "gradual suppression of the Catholic Church in Germany".[128] Anton Gill wrote that "with his usual irresistible, bullying technique, Hitler proceeded to "take a mile where he had been given an inch" and closed all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:[129]

It quickly became clear that [Hitler] intended to imprison the Catholics, as it were, in their own churches. They could celebrate mass and retain their rituals as much as they liked, but they could have nothing at all to do with German society otherwise. Catholic schools and newspapers were closed, and a propaganda campaign against the Catholics was launched.

— Extract from An Honourable Defeat by Anton Gill

Immediately prior to the signing of the Concordat, the Nazis had promulgated the sterilization law—the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring—an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League.[130] Political Catholicism was also among the targets of Hitler's 1934 Long Knives purge: the head of Catholic Action, Erich Klausener, Papen's speech writer and adviser Edgar Jung (also a Catholic Action worker); and the national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, Adalbert Probst. Former Centre Party Chancellor, Heinrich Brüning narrowly escaped execution.[131][132][133] William Shirer wrote that the German people were not greatly aroused by the persecution of the churches by the Nazi Government. The majority were not moved to face death or imprisonment for the sake of freedom of worship, being too impressed by Hitler's early foreign policy successes and the restoration of the German economy. Few, he said, "paused to reflect that the Nazis intended to destroy Christianity in Germany, and substitute old paganism of tribal Germanic gods and the new paganism of the Nazi extremists."[50] Anti-Nazi sentiment grew in Catholic circles as the Nazi government increased its repressive measures against their activities.[29]

- Targeting of clergy

Clergy as well as members of male and female religious orders and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".[130] Priests were watched closely and frequently denounced, arrested and sent to concentration camps.[134] From 1940, a dedicated Clergy Barracks had been established at Dachau concentration camp.[135] Intimidation of clergy was widespread and Cardinal Faulhaber was shot at. Cardinal Innitzer had his Vienna residence ransacked in October 1938 and Bishop Sproll of Rottenburg was jostled and his home vandalised. In 1937, the New York Times reported that Christmas would see "several thousand Catholic clergymen in prison." Propaganda satirized the clergy, including Anderl Kern's play The Last Peasant.[136] Under Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Himmler, the Security Police and the SD were responsible for suppressing internal and external enemies of the Nazi state. Among those enemies were "political churches" – such as Lutheran and Catholic clergy who opposed Hitler. Such dissidents were arrested and sent to concentration camps.[137] In the 1936 campaign against the monasteries and convents, the authorities charged 276 members of religious orders with the offence of "homosexuality".[138] 1935-6 was the height of the "immorality" trials against priests, monks, lay-brothers and nuns. In the United States, protests were organised in response to the sham trials, including a June 1936, petition signed by 48 clergymen, including rabbis and Protestant pastors: "We lodge a solemn protest against the almost unique brutality of the attacks launched by the German government charging Catholic clergy with gross immorality ... in the hope that the ultimate suppression of all Jewish and Christian beliefs by the totalitarian state can be effected."[139] Winston Churchill wrote disapprovingly in the British press of Germany's treatment of "the Jews, Protestants and Catholics of Germany".[140]

Since senior clerics could rely on a degree of popular support from the faithful the German government had to consider the possibility of nationwide protests.[141] While hundreds of ordinary priests and members of monastic orders were sent to concentration camps throughout the Nazi period, only one German Catholic bishop was briefly imprisoned in a concentration camp and another expelled from his diocese.[142] From 1940, the Gestapo launched an intense persecution of the monasteries invading, searching and seizing them. The Provincial of the Dominican Province of Teutonia, Laurentius Siemer, a spiritual leader of the German Resistance was influential in the Committee for Matters Relating to the Orders, which formed in response to Nazi attacks against Catholic monasteries and aimed to encourage the bishops to intercede on behalf of the Orders and oppose the Nazi state more emphatically.[143][144] Figures like Galen and Preysing attempted to protect German priests from arrest.[145][146][147]

- Suppression of Catholic press

The flourishing Catholic press of Germany faced censorship and closure. In March 1941, Goebbels banned all church press, on the pretext of a "paper shortage".[148] In 1933, the Nazis established a Reich Chamber of Authorship and Reich Press Chamber under the Reich Cultural Chamber of the Ministry for Propaganda. Dissident writers were terrorized. The June – July 1934 Night of the Long Knives purge was the culmination of this early campaign.[149] Fritz Gerlich, the editor of Munich's Catholic weekly, Der Gerade Weg, was killed in the purge for his strident criticism of the Nazis.[150] Writer and theologian Dietrich von Hildebrand was forced to flee Germany. The poet Ernst Wiechert protested the government's attitudes to the arts, calling them "spiritual murder". He was arrested and taken to Dachau Concentration Camp.[151] Hundreds of arrests and closure of Catholic presses followed the issuing of Pope Pius XI's Mit brennender Sorge anti-Nazi encyclical.[152] Nikolaus Gross, a Christian Trade Unionist, and director of the West German Workers' Newspaper Westdeutschen Arbeiterzeitung, was declared a martyr and beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2001. Declared an enemy of the state in 1938, his a newspaper was shut down. He was arrested in the July Plot round up, and executed on 23 January 1945.[153][154]

- Suppression of Catholic education

Catholic schools were a major battleground in the church struggle. In 1933, the Nazi school superintendent of Munster issued a decree religious instruction be combined with discussion of the "demoralising power" of the "people of Israel", Bishop Clemens von Galen of Münster refused, writing that such interference in curriculum was a breach of the Concordat and he feared children would be confused as to their "obligation to act with charity to all men" and as to the historical mission of the people of Israel.[155] Often Galen directly protested to Hitler over violations of the Concordat. In 1936, Nazis removed crucifixes in school. Protest by Galen led to public demonstration.[156] Hitler sometimes allowed pressure to be placed on German parents to remove children from religious classes to be given ideological instruction in its place, while in elite Nazi schools, Christian prayers were replaced with Teutonic rituals and sun-worship.[157] Church kindergartens were closed and Catholic welfare programs were restricted on the basis they assisted the "racially unfit". Parents were coerced into removing their children from Catholic schools. In Bavaria, teaching positions formerly allotted to nuns were awarded to secular teachers and denominational schools transformed into "Community schools".[139] In 1937, authorities in Upper Bavaria attempted to replace Catholic schools with "common schools". Cardinal Faulhaber offered fierce resistance.[158] By 1939 all Catholic denominational schools had been disbanded or converted to public facilities.[16]

- "War on the Church"

After constant confrontations, by late 1935, Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen of Münster was urging a joint pastoral letter protesting an "underground war" against the church.[155] By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, became highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI issued the Mit brennender Sorge encyclical – accusing the Nazi Government of violations of the 1933 Concordat, and it was sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church".[130] The Nazis responded with an intensification of the church struggle beginning around April.[51] Goebbels noted heightened verbal attacks on the clergy from Hitler in his diary and wrote that Hitler had approved the trumped up "immorality trials" against clergy and anti-church propaganda campaign. Goebbels' orchestrated attack included a staged "morality trial" of 37 Franciscans.[51] At the outbreak of World War II, Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda issued threats and applied intense pressure on the Churches to voice support for the war, and the Gestapo banned church meetings for a few weeks. In the first few months of the war, the German churches complied.[159] No denunciations of the invasion of Poland, nor the Blitzkrieg were issued.[160] The Catholic bishops stated, "We appeal to the faithful to join in ardent prayer that God's providence may lead this war to blessed success for Fatherland and people."[159] Despite such protestation of loyalty to the Fatherland, the anti-church radical Reinhard Heydrich determined that support from church leaders could not be expected because of the nature of their doctrines and internationalism, and wanted to cripple the political activities of clergy. He devised measures to restrict the operation of the churches under cover of war time exigencies, such as reducing resources available to church presses on the basis of rationing, prohibiting pilgrimages and large church gatherings on the basis of transportation difficulties. Churches were closed for being "too far from bomb shelters". Bells were melted down and presses were closed.[161]

With the expansion of the war in the East from 1941 came an expansion of Germany's attack on the churches. Monasteries and convents were targeted and expropriation of church properties surged. Nazi authorities claimed the properties were needed for wartime necessities such as hospitals, or accommodation for refugees or children, but in fact used them for their own purposes. "Hostility to the state" was a common cause given for the confiscations, and the action of a single member of a monastery could result in seizure. The Jesuits were especially targeted.[162] The Papal Nuncio Cesare Orsenigo and Cardinal Bertram complained constantly to the authorities but were told to expect more requisitions owing to war-time needs.[163] Over 300 monasteries and other institutions were expropriated by the SS.[164] On 22 March 1942, the German Bishops issued a pastoral letter on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church".[19] The letter launched a defense of human rights, the rule of law and accused the Reich Government of "unjust oppression and hated struggle against Christianity and the Church", despite the loyalty of German Catholics to the Fatherland, and brave service of Catholics soldiers.[20]

- Long-term plans

In January 1934, Hitler had appointed neo-pagan and anti-Catholic Alfred Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich.[50][67] In 1934, the Sanctum Officium in Rome recommended that Rosenberg's book be put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion".[165] During the War, Rosenberg outlined the future envisioned by the Hitler government for religion in Germany, with a thirty-point program for the future of the German churches. Among its articles: the National Reich Church of Germany was to claim exclusive control over all churches; publication of the Bible was to cease; crucifixes, Bibles and saints were to be removed from altars; and Mein Kampf was to be placed on altars as "to the German nation and therefore to God the most sacred book"; and the Christian Cross was to be removed from all churches and replaced with the swastika.[50]

Impact of the Spanish Civil War

[edit]The Spanish Civil War (1936–39) saw Nationalists (aided by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany) and Republicans (aided by the Soviet Union, Mexico as well as International Brigades of volunteers, most of whom were under the command of the Comintern). The Republican president, Manuel Azaña, was anticlerical, while the Nationalist Generalissimo Francisco Franco, established a longstanding Fascist dictatorship which restored some privileges to the Church.[166] In a Table Talk of 7 June 1942, Hitler said he believed that Franco's accommodation of the Church was an error: "one makes a great mistake if one thinks that one can make a collaborator of the Church by accepting a compromise. The whole international outlook and political interest of the Catholic Church in Spain render inevitable conflict between the Church and Franco regime".[167] The Nazis portrayed the war as a contest between civilization and Bolshevism. According to historian, Beth Griech-Polelle, many church leaders "implicitly embraced the idea that behind the Republican forces stood a vast Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy intent on destroying Christian civilization."[168] Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda served as the main source of German domestic coverage of the war. Goebbels, like Hitler, frequently mentioned the so-called link between Jewishness and communism. Goebbels instructed the press to call the Republican side simply Bolsheviks—and not to mention German military involvement. Against this backdrop, in August 1936, the German bishops met for their annual conference at Fulda. The bishops produced a joint pastoral letter regarding the Spanish Civil War: "Therefore, German unity should not be sacrificed to religious antagonism, quarrels, contempt, and struggles. Rather our national power of resistance must be increased and strengthened so that not only may Europe be freed from Bolshevism by us, but also that the whole civilized world may be indebted to us."[169]

- Faulhaber meets Hitler

Goebbels noted the mood of Hitler in his diary on 25 October: "Trials against the Catholic Church temporarily stopped. Possibly wants peace, at least temporarily. Now a battle with Bolshevism. Wants to speak with Faulhaber".[170] As Nuncio, Cesare Orsenigo arranged for Cardinal Faulhaber to have a private meeting with Hitler.[169] On November 4, 1936, Hitler met Faulhaber. Hitler spoke for the first hour, then Faulhaber told him the Nazi government had been waging war on the church for three years—600 religious teachers had lost their jobs in Bavaria alone—and the number rose to 1700. The government instituted laws the Church could not accept—like the sterilization of criminals and the handicapped. Faulhaber stated, "When your officials or your laws offend Church dogma or the laws of morality, and in so doing offend our conscience, then we must be able to articulate this as responsible defenders of moral laws".[170] Hitler told Faulhaber religion was critical for the state, his goal was to protect the German people from congenitally afflicted criminals such as now wreak havoc in Spain. Faulhaber replied the Church would "not refuse the state the right to keep these pests away from the national community within the framework of moral law."[171] Hitler argued the radical Nazis could not be contained until there was peace with the Church and that either the Nazis and the Church would fight Bolshevism together, or there would be war against the Church.[170] Kershaw cites the meeting as an example of Hitler's ability to "pull the wool over the eyes even of hardened critics", "Faulhaber—a man of sharp acumen, who often courageously criticized the Nazi attacks on the Catholic Church, went away convinced Hitler was deeply religious".[172] On November 18, Faulhaber met with leading members of the German hierarchy to ask them to remind parishioners of the errors of communism outlined in Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum novarum. On November 19, Pius XI announced communism had moved to the head of the list of "errors" and a clear statement was needed.[171] On November 25 Faulhaber told the Bavarian bishops that he promised Hitler the bishops would issue pastoral letter to condemned "Bolshevism which represents the greatest danger for the peace of Europe and the Christian civilization of our country".[171] He stated, the letter "will once again affirm our loyalty and positive attitude, demanded by the Fourth Commandment, toward today's form of government and the Fuhrer. "[173]

On December 24, 1936 the hierarchy ordered its priests to read the pastoral letter, On the Defense against Bolshevism, from all the pulpits on January 7, 1937. The letter included the statement:

the fateful hour has come for our nation and for the Christian culture of the western work. The Fuhrer saw the march of Bolshevism from afar and turned his mind and energies towards averting this enormous danger from the German people and the whole western world. The German bishops consider it their duty to do their utmost to support the leader of the Reich with every available means in this defense.

Hitler's promise to Faulhaber, to clear up small problems between the Catholic Church and the Nazi state, never materialized. Faulhaber, Galen, and Pius XI, continued to oppose Communism throughout their tenure as anxieties reached a highpoint in the 1930s with what the Vatican termed the 'red triangle', formed by the USSR, Republican Spain and revolutionary Mexico. A series of encyclicals followed: Bona Sana (1920), Miserentissimus Redemtor (1928), Caritate Christi Compusli (1932)and most importantly Divini redemptoris (1937). All of which condemned communism.[174]

Catholic opposition to Nazism inside Germany: 1933–1945

[edit]Catholic resistance

[edit]The 1933 Concordat between Germany and the Vatican prohibited clergy from participating in politics, weakening the opposition offered by German Catholic leaders.[175] Still, the clergy were among the first major components of the German Resistance. "From the very beginning", wrote Hamerow, "some churchmen expressed, quite directly at times, their reservations about the new order. In fact, those reservations gradually came to form a coherent, systematic critique of many of the teachings of National Socialism."[176] Later, the most trenchant public criticism of the Nazis came from some of Germany's religious leaders. The government was reluctant to move against them since they could claim to merely attend the spiritual welfare of their flocks, "what they had to say was at times so critical of the central doctrines of National Socialism that to say it required great boldness", and became resistors. Their resistance was directed not only against intrusions by the government into church governance, arrests of clergy, and expropriation of church property, but also, matters like euthanasia and eugenics, the fundamentals of human rights and justice as the foundation of a political system.[177]

Neither the Catholic or Protestant churches were prepared to openly oppose the Nazi State. While offering, in the words of Kershaw, "something less than fundamental resistance to Nazism", the churches "engaged in a bitter war of attrition with the regime, receiving the demonstrative backing of millions of churchgoers. Applause for Church leaders whenever they appeared in public, swollen attendances at events such as Corpus Christi Day processions, and packed church services were outward signs of the struggle of ... especially of the Catholic Church—against Nazi oppression". While the Church ultimately failed to protect its youth organisations and schools, it did have some successes in mobilizing public opinion to alter government policies. As in the case of the attempt to remove crucifixes from classrooms.[178] The churches did provide the earliest and most enduring centres of systematic opposition to Nazi policies. Christian morality and the anti-Church policies of the Nazis motivated many German resistors and provided impetus for the "moral revolt" of individuals in their efforts to overthrow Hitler.[179] Institutionally, the Catholic Church in Germany offered organised, systematic and consistent resistance to government policies which infringed on ecclesiastical autonomy.[180] In his history of the German Resistance, Hoffmann writes, from the beginning:[181]

[The Catholic Church] could not silently accept the general persecution, regimentation or oppression, nor in particular the sterilization law of summer 1933. Over the years until the outbreak of war Catholic resistance stiffened until finally its most eminent spokesman was the Pope himself with his encyclical Mit brennender Sorge ... of 14 March 1937, read from all German Catholic pulpits. Clemens August Graf von Galen, Bishop of Münster, was typical of the many fearless Catholic speakers. In general terms, therefore, the churches were the only major organisations to offer comparatively early and open resistance: they remained so in later years.

— Extract from The History of the German Resistance 1933–1945 by Peter Hoffmann

- Early political resistance

Political Catholicism was a target of the Hitler government. The formerly influential Centre Party and Bavarian People's Party were dissolved under terrorisation. Following "Hitler's seizure of power", opposition politicians began planning how he might be overthrown. Old political opponents faced a final opportunity to halt the Nazification of Germany, however non-Nazi parties were prohibited under the proclamation of the "Unity of Party and State".[183] Former Centre Party leader and Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning looked to oust Hitler, along with military chiefs Kurt von Schleicher and Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord.[131] Erich Klausener, an influential civil servant and president of Berlin's Catholic Action group organised Catholic conventions in Berlin in 1933–34. At the 1934 rally, he spoke against political oppression to a crowd of 60,000 following mass; just six nights before Hitler struck in a bloody purge.[184] The Conservative Catholic nobleman Franz von Papen, who had helped Hitler to power and was serving as the Deputy Reich Chancellor, delivered an indictment of the Nazi government in his Marburg speech of 17 June 1934.[131][185] Papen's speech writer and advisor Edgar Jung, a Catholic Action worker, seized the opportunity to reassert the Christian foundation of the state and the need to avoid agitation and propaganda.[186] Jung's speech pleaded for religious freedom, and rejected totalitarian aspirations in the field of religion. It was hoped the speech might spur a rising, centered on Hindenberg, Papen and the army.[187]

Hitler decided to kill his chief political opponents in the Night of the Long Knives purge. It lasted two days over 30 June-1 July 1934.[188] His leading rivals in the Nazi movement were murdered, along with over 100 opposition figures, including high-profile Catholics. Klausener became the first Catholic martyr, while Hitler personally ordered the arrest of Jung and his transfer to Gestapo headquarters, Berlin where he too was killed.[189] The Church had resisted attempts by the new Government to close its youth organisations and Adalbert Probst, the national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association, was also killed.[133][133] The Catholic press was targeted too, with anti-Nazi journalist Fritz Gerlich among those murdered.[150] On 2 August 1934, the aged President von Hindenberg died. The offices of President and Chancellor were combined, and Hitler ordered the Army to swear an oath directly to him. Hitler declared his "revolution" complete.[190]

- Clerical resistors

Historian of the German Resistance, Joachim Fest wrote that at first the Church had been quite hostile to Nazism and "its bishops energetically denounced the 'false doctrines' of the Nazis", however, its opposition weakened considerably after the Concordat. Cardinal Bertram "developed an ineffectual protest system" to satisfy the demands of other bishops, without annoying the authorities.[175] Firmer resistance by Catholic leaders gradually reasserted itself by the individual actions of leading churchmen like Joseph Frings, Konrad von Preysing, Clemens August Graf von Galen, Conrad Gröber and Michael von Faulhaber.[191][192][193] According to Fest, the government responded with "occasional arrests, the withdrawal of teaching privileges, and the seizure of church publishing houses and printing facilities" and "Resistance remained largely a matter of individual conscience. In general they [both churches] attempted merely to assert their own rights and only rarely issued pastoral letters or declarations indicating any fundamental objection to Nazi ideology." Nevertheless, wrote Fest, the churches, more than any other institutions, "provided a forum in which individuals could distance themselves from the regime".[175]

The Nazis never felt strong enough to arrest or execute senior office holders of the Catholic Church in Germany. Thus bishops were able to criticize aspects of Nazi totalitarianism. Lesser senior figures faced imprisonment or execution. An estimated one third of German priests faced some form of reprisal from the Nazi Government and 400 German priests were sent the dedicated Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp alone. Among the best known German priest martyrs were the Jesuit Alfred Delp and Fr Bernhard Lichtenberg.[178] Fr. Max Josef Metzger, founder of the German Catholics' Peace Association, was arrested for the last time in June 1943 after being denounced by a mail courier for attempting to send a memorandum on the reorganisation of the German state and its integration into a future system of world peace. He was executed on April 17, 1944.[194] Laurentius Siemer, provincial of the Provincial of the Dominican Province of Teutonia, and Augustin Rösch, Jesuit Provincial of Bavaria, were among the high-ranking members of orders who became active in the Resistance – both only narrowly survived the war, following discovery of their knowledge of the July Plot. Bernhard Lichtenberg, and the Jesuit Rupert Mayer are among the priest resistors posthumously honored with beatification. While hundreds of ordinary priests and members of monastic orders were sent to concentration camps, just one German Catholic bishop was briefly imprisoned in a concentration camp, and just one other expelled from his diocese.[195] This reflected also the cautious approach adopted by the hierarchy, who felt secure only in commenting on matters which transgressed on the ecclesiastical sphere.[196] Albert Speer wrote that when Hitler was read passages from a defiant sermon or pastoral letter, he would become furious, and the fact that he "could not immediately retaliate raised him to a white heat".[197]

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber gained an early reputation as a critic of the Nazi movement.[198] Soon after the Nazi takeover, his three Advent sermons of 1933, entitled Judaism, Christianity, and Germany, affirmed the Jewish origins of Christ and the Bible.[63] Though cautiously framed as a discussion of historical Judaism, his sermons denounced the Nazi extremists who were calling for the Bible to be purged of the "Jewish" Old Testament, which he saw as undermining "the basis of Catholicism.[199] Hamerow wrote that Faulhaber would look to avoid conflict with the state over issues not strictly pertaining to the church, but on issues involving the defense of Catholics he "refused to compromise or retreat".[200] On November 4, 1936, Hitler and Faulhaber met. Faulhaber told Hitler that the Nazi government had been waging war on the church for three years and had instituted laws the Church could not accept—like the sterilization of criminals and the handicapped. While the Catholic Church respected the notion of authority, he told the Dictator, "when your officials or your laws offend Church dogma or the laws of morality, and in so doing offend our conscience, then we must be able to articulate this as responsible defenders of moral laws".[170] Attempts on his life were made in 1934 and in 1938. He worked with American occupation forces after the war, and received the West German Republic's highest award, the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit.[63] Among the most firm and consistent of senior Catholics to oppose the Nazis was Konrad von Preysing. Preysing was appointed as Bishop of Berlin in 1935. He was loathed by Hitler.[201] He opposed the appeasing attitudes of Bertram towards the Nazis and worked with leading members of the resistance Carl Goerdeler and Helmuth James Graf von Moltke. He was part of the five-member commission that prepared the 1937 Mit brennender Sorge anti-Nazi encyclical of Pius XI, and sought to block the Nazi closure of Catholic schools and arrests of church officials.[202][203] In 1938, he became one of the co-founders of the Hilfswerk beim Bischöflichen Ordinariat Berlin (Welfare Office of the Berlin Diocese Office). He extended care to Jews and protested the Nazi euthanasia programme.[203] His Advent Pastoral Letters of 1942–43 on the nature of human rights reflected the anti-Nazi theology of the Barmen Declaration of the Confessing Church, leading one to be broadcast in German by the BBC. In 1944, Preysing met with and gave a blessing to Claus von Stauffenberg, in the lead up to the July Plot to assassinate Hitler, and spoke with the resistance leader on whether the need for radical change could justify tyrannicide.[202] Despite Preysing's open opposition, the Nazis did not dare arrest him and several months after the war he was named a cardinal by Pope Pius XII.[203]