Marxist–Leninist atheism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Marxist–Leninist atheism, also known as Marxist–Leninist scientific atheism, is the antireligious element of Marxism–Leninism.[1][2] Based upon a dialectical-materialist understanding of humanity's place in nature, Marxist–Leninist atheism proposes that religion is the opium of the people; thus, Marxism–Leninism advocates atheism, rather than religious belief.[3][4][5]

To support those ideological premises, Marxist–Leninist atheism proposes an explanation for origin of religion and explains methods for the scientific criticism of religion.[6] The philosophic roots of Marxist–Leninist atheism are in the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) and of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), of Karl Marx (1818–1883) and of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924).[7]

Marxist–Leninist atheism informed public policy in various nations, such as the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China for example.[8][9] Some non-Soviet Marxists opposed this antireligious stance, and in certain forms of Marxist thinking, such as the liberation theology movements in Latin America, Marxist–Leninist atheism was rejected entirely.[10]

Philosophical bases

[edit]Ludwig Feuerbach

[edit]

In training as a philosopher in the early 19th century, Karl Marx participated in debates about the philosophy of religion, specifically about the interpretations presented in Hegelianism, i.e. "What is rational is real; and what is real is rational."[11] In those debates about reason and reality, the Hegelians considered philosophy an intellectual enterprise in service to the insights of Christian religious comprehension, which Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel had elaborately rationalized in The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807). Although critical of contemporary religion, as a 19th-century intellectual, Hegel pursued the ontology and the epistemology of Christianity, as a personal interest compatible with Christian theological explanations of Dasein — explanations of the questions of existence and of being — which he clarified, systematized, and justified in his philosophy.[12]

After his death in 1831, Hegel's philosophy about being and existence was debated by the Young Hegelians and the materialist atheists — such as Ludwig Feuerbach — who rejected all religious philosophy as a way of running the world; Karl Marx sided with the philosophy of the materialist atheists. Feuerbach separated philosophy from religion in order to grant intellectual autonomy to philosophers in their interpretations of material reality. He objected to the religious basis of Hegel's philosophy of spirit in order to critically analyse the basic concepts of theology, and he redirected philosophy from the heavens to the Earth, to the subjects of human dignity and the meaning of life, of what is morality and of what is the purpose of existence,[13] concluding that humanity as a species (but just not as individuals) possessed within itself all the attributes that merited worship and that people had created God as a reflection of these attributes.[14] About the conceptual separateness of Man from God, in The Essence of Christianity (1841), Feuerbach said:

But the idea of deity coincides with the idea of humanity. All divine attributes, all the attributes which make God God, are attributes of the [human] species — attributes which in the individual [person] are limited, but the limits of which are abolished in the essence of the species, and even in its existence, in so far as it has its complete existence only in all men taken together.[15]

Feuerbach thought that religion exercised power over the human mind through "the promotion of fear from the mystical forces of the Heaven",[16] and with "an intensive hatred of the old God" said that houses of worship should be systematically destroyed and religious institutions eradicated.[17] Experienced in that praxis of materialist philosophy, thought, and action, the apprentice Karl Marx became a radical philosopher.[18][19]

Karl Marx

[edit]

In his rejection of all religious thought, Marx considered the contributions of religion over the centuries to be unimportant and irrelevant to the future of humanity. The autonomy of humanity from the realm of supernatural forces was considered by Marx as an axiomatic ontological truth that had been developed since ancient times, and he considered it to have an even more respectable tradition than Christianity.[20] Marx held that the churches invented religion to justify the ruling classes' exploitation of labour of the working classes, by way of a socially stratified industrial society; as such, religion is a drug that gives an emotional escape from the real world.[21] In A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx described the contradictory nature of religious sentiment, that:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering, and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heart-less world, and the soul of soul-less conditions. It [religion] is the opium of the people.[22]

Thus for Marx atheist philosophy liberated men and women from suppressing their innate potential as human beings, and allowed people to intellectually understand that they possess individual human agency, and thus are masters of their individual reality, because the earthly authority of supernatural deities is not real. Marx opposed the social-control function of religion, which the churches realised by way of societal atomization; the anomie and the social alienation that psychologically divide human beings from themselves (as individual men and women) and that alienate people from each other (as parts of a social community). Hence, the social authority of theology (religious ideology) must be removed from the law, the social norms, and the traditions with which men govern society. In that vein of political emancipation, represented in the culturally progressive concepts of citizen and citizenship as a social identity, in On the Jewish Question, Marx said that:

The decomposition of man into Jew and citizen, Protestant and citizen, religious man and citizen, is neither a deception directed against citizenhood, nor is it a circumvention of political emancipation, it is political emancipation itself, the political method of emancipating oneself from religion. Of course, in periods when the political state, as such, is born violently out of civil society, when political liberation is the form in which men strive to achieve their liberation, the state can and must go as far as the abolition of religion, the destruction of religion. But it can do so only in the same way that it proceeds to the abolition of private property, to the maximum, to confiscation, to progressive taxation, just as it goes as far as the abolition of life, the guillotine.

At times of special self-confidence, political life seeks to suppress its prerequisite, civil society, and the elements composing this society, and to constitute itself as the real species-life of man, devoid of contradictions. But, it can achieve this only by coming into violent contradiction with its own conditions of life, only by declaring the revolution to be permanent, and, therefore, the political drama necessarily ends with the re-establishment of religion, private property, and all elements of civil society, just as war ends with peace.[23]

Therefore, because organised religion is a human product derived from the objective material conditions, and that economic systems, such as capitalism, affect the material conditions of society, the abolition of unequal systems of political economy and of stratified social classes would wither away the State and the official religion, consequent to the establishment of a communist society, featuring neither a formal State apparatus nor a social-class system. About the nature and social-control function of religious sentiment, in A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (1843), Marx said that:

The abolition of religion, as the illusory happiness of the people, is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.[24]

In that way, Marx transformed Feuerbach's antireligious philosophy into a political praxis, and into a philosophic basis of his nascent ideology, dialectical materialism. In Private Property and Communism (1845), Marx said that "Communism begins from the outset (Owen) with atheism; but atheism is, at first, far from being communism; indeed, that atheism is still mostly an abstraction",[25] and refined the atheism of Feuerbach into a considered critique of the material (socio-economic) conditions responsible for the invention of religion. He therefore held that atheism was the philosophical foundation stone of his ideology, but in itself was insufficient. About the social artifice of religious sentiment, in the Theses on Feuerbach, Marx said:

Feuerbach starts out from the fact of religious self-alienation, of the duplication of the world into a religious world and a secular one. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis. But that the secular basis detaches itself from itself, and [then] establishes itself as an independent realm in the clouds can only be explained by the cleavages and self-contradictions within this secular basis. The latter must, therefore, in itself, be both understood in its contradiction and revolutionized in practice. Thus, for instance, after the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then, itself, be destroyed in theory and in practice. Feuerbach, consequently, does not see that the "religious sentiment" is, itself, a social product, and that the abstract individual [person] whom he analyses belongs to a particular form of society.[26]

The philosophy of dialectical materialism proposed that the existential condition of being human naturally resulted from the interplay of the material forces (earth, wind, and fire) that exist in the physical world. That religion originated as psychological solace for the exploited workers who live the reality of wage slavery in an industrial society. Thus, despite the working-class origin of organised religion, the clergy allowed the ruling class to control religious sentiment (the praxis of religion), which grants control of all society — the middle class, the working class, and the proletariat — with Christian slaves hoping for a rewarding after-life. In The German Ideology (1845), about the psychology of religious faith, Marx said that:

It is self-evident, moreover, that "spectres", "bonds", [and] "the higher being", "concept", [and] "scruple", are merely the idealistic, spiritual expression, the conception, apparently, of the isolated individual [person], the image of very empirical fetters and limitations, within which the mode of production of life, and the form of [social] intercourse coupled with it, move.[27]

In the establishment of a communist society, the philosophy of Marxist–Leninist atheism interprets the social degeneration of organized religion — from psychological-solace to social-control — to justify the revolutionary abolition of an official state religion, and its replacement with official atheism, the latter being characteristic of a Marxist–Leninist state.[28]

Friedrich Engels

[edit]

In Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Ideology (1846) and in the Anti-Dühring (1878), Friedrich Engels addressed contemporary social problems with critiques of the idealistic worldview, especially religious interpretations of the material reality of the world. Engels proposed that religion is a fantasy about supernatural powers controlling and determining humanity's material poverty and dehumanizing moral squalor since early in human history; yet that such a lack of human control over human existence would end with the abolition of religion. That by way of theism, a people's need to believe in a deity, as a spiritual reflection of the self, religion would gradually disappear. In the Anti-Dühring, Engels said:

. . . and when this act has been accomplished, when society, by taking possession of all means of production, and using them on a planned basis, has freed itself, and all its members, from the bondage in which they are now held, by these means of production, which they, themselves, have produced, but which confront them as an irresistible alien force, when, therefore, man no longer merely proposes, but also disposes — only then will the last alien force, which is still reflected in religion, vanish; and with it will also vanish the religious reflection itself, for the simple reason that then there will be nothing left to reflect.[29]

Engels considered religion as a false consciousness incompatible with communist philosophy and urged the communist parties of the First International to advocate atheist politics in their home countries, and recommended scientific education as a means to overcome the mysticism and superstitions of people who required a religious explanation of the real world.[30] In light of the scientific progress of the Industrial Revolution, the speculative philosophy of theology became obsolete in determining a place for every person in society. In the Anti-Dühring, Engels said:

The real unity of the world consists in its materiality, and this is proved, not by a few juggled phrases, but by a long and wearisome development of philosophy and natural science.[31]

By scientific advances, socio-economic and cultural progress required that atheistic materialism become a science rather than remain a philosophy apart from the sciences. In the "Negation of a Negation" section of the Anti-Dühring, Engels said:

This modern materialism, the negation of the negation, is not the mere re-establishment of the old, but adds to the permanent foundations of this old materialism the whole thought-content of two thousand years of development of philosophy and natural science, as well as of the history of these two thousand years. It [materialism] is no longer a philosophy at all, but simply a world outlook, which has to establish its validity and be applied, not in a science of sciences, standing apart, but in the real sciences. Philosophy is therefore sublated here, that is, “both overcome and preserved”; overcome as regards its form, and preserved as regards its real content.[32]

Vladimir Lenin

[edit]

As a revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin said that a true communist would always promote atheism and combat religion, because it is the psychological opiate that robs people of their human agency, of their volition, as men and women, to control their own reality.[17][33] To combat the political legitimacy of religion, Lenin adapted the atheism of Marx and Engels to the Russian Empire.[17] About the social-control function of religion, in "Socialism and Religion" (1905), Lenin said:

Religion is one of the forms of spiritual oppression, which everywhere weighs down heavily upon the masses of the people, over-burdened by their perpetual work for others, by want and isolation. Impotence, of the exploited classes in their struggle against the exploiters, just as inevitably, gives rise to the belief in a better life after death, as [the] impotence of the savage in his battle with Nature gives rise to belief in gods, devils, miracles, and the like.

Those who toil and live in want all their lives are taught, by religion, to be submissive and patient while here on earth, and to take comfort in the hope of a heavenly reward. But those who live by the labour of others are taught, by religion, to practise charity while on earth, thus offering them a very cheap way of justifying their entire existence as exploiters, and selling them, at a moderate price, tickets to well-being in heaven. Religion is opium for the people. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze, in which the slaves of capital drown their human image, their demand for a life more or less worthy of man.[34]

Since the social ideology of the Eastern Orthodox Church supported the Tsarist monarchy, voiding the credibility of religion would void the political legitimacy of the Tsar as the Russian head of state. Additionally, the populace also needed to be prepared in order to make a transition from religious beliefs to atheism, as Soviet Communism would require of them.[35] Scientific atheism became a philosophic basis of Marxism–Leninism, the ideology of the Communist Party in Russia, as with other Marxist-Leninist countries, such as the People's Republic of Albania.[36][37]

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin enshrined the dissemination of Marxist-Leninist atheism as a task of the Communist Party, believing it to be an "urgent necessity."[38] Lenin held a hostile attitude towards religion and this came to characterize Bolshevik atheism.[38] He was a staunch critic of Anatoli Lunacharsky, who proposed the concept of God-Building, which held that because religion "cultivated in the masses emotion, moral values, [and] desire", revolutionaries should take advantage of that fact.[38] As such, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin "appealed to militant atheism as a criterion for the sincerity of Marxist commitments as a testing principle."[38] This rigid stance in favour of atheism and against religion resulted in the alienation of "some of the sympathetic, leftist-minded yet religious believing intellectuals, workers or peasants."[38]

Soviet Union

[edit]

The pragmatic policies of Lenin and the Communist Party indicated that religion was to be tolerated and suppressed as required by political conditions, yet there remained the ideal of an officially atheist society.[39][40][41]

To the Russians, Lenin communicated the atheist worldview of materialism:

Marxism is materialism. As such, it is as relentlessly hostile to religion as was the materialism of the eighteenth-century Encyclopaedists or the materialism of Feuerbach. This is beyond doubt. But the dialectical materialism of Marx and Engels goes further than the Encyclopaedists and Feuerbach, for it applies the materialist philosophy to the domain of history, to the domain of the social sciences. We must combat religion — that is the ABC of all materialism, and consequently of Marxism. But Marxism is not a materialism which has stopped at the ABC. Marxism goes further. It says: "We must know how to combat religion, and in order to do so we must explain the source of faith and religion among the masses in a materialist way. The combating of religion cannot be confined to abstract ideological preaching, and it must not be reduced to such preaching. It must be linked up with the concrete practice of the class movement, which aims at eliminating the social roots of religion."[33]

The establishment of a socialist society in Russia required changing the socio-political consciousness of the people, thus, combating religion, mysticism, and the supernatural was a philosophic requirement for membership to the Communist Party.[42][43] For Lenin, the true socialist is a revolutionary who always combats religion and religious sentiment as enemies of reason, science, and socio-economic progress.[44]

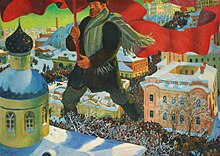

The Bolshevik government's anti-religion campaigns featured propaganda, anti-religious legislation, secular universal-education, anti-religious discrimination, political harassment, continual arrests and political violence.[8] Initially, the Bolsheviks expected that religion would wither away with the establishment of socialism, hence after the October Revolution they tolerated most religions, except for the Eastern Orthodox Church who supported Tsarist autocracy. Yet by the late 1920s, when religion had not withered away, the Bolshevik government began anti-religion campaigns (1928–1941)[45] that persecuted "bishops, priests, and lay believers" of all Christian denominations and had them "arrested, shot, and sent to labour camps".[46] In the east, Buddhist Lamaist priests "were rounded up in Mongolia, by the NKVD in concert with its local affiliate, executed on the spot or shipped off to the Soviet Union to be shot or die at hard labor in the mushrooming GULAG system" of labour camps;[47] and by 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, 40,000 churches and 25,000 mosques had been closed and converted into schools, cinemas and clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or museums of scientific atheism.[48]

In 1959, the academic course Fundamentals of Scientific Atheism (Osnovy nauchnogo ateizma) was "introduced into the curriculum of all higher educational institutions" in the Soviet Union. In 1964, it was made compulsory for all pupils after a "paucity of student response".[49]

See also

[edit]- Cultural Revolution

- Cultural Revolution in the Soviet Union

- Christianity in East Germany

- God-Building

- Institute of Scientific Atheism

- Jewish Bolshevism

- Marxism and religion

- Opium of the people

- Persecution of Christians in the Eastern Bloc

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Persecution of Muslims in the former Soviet Union

- Polish anti-religious campaign

- Red Terror

- Religion in the Soviet Union

- Religious communism

- Anti-religious campaign of Communist Romania

- State atheism

- Soviet Union anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

- Soviet Union anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

- Soviet Union anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

- Soviet Union anti-religious campaign (1970s–1987)

- Soviet Union anti-religious legislation

References

[edit]- ^ Institute of Scientific Atheism of the Academy of Social Sciences (1981). Questions of Scientific Atheism: “Marxist–Leninist atheism, with all its content is directed to the development of the abilities of the individual [person], religion deprives a person of his [and her] own “I”, doubles consciousness, creates conditions for him. . . . ”

- ^ Tesař, Jan (15 July 2019). The History of Scientific Atheism: A Comparative Study of Czechoslovakia and Soviet Union (1954–1991). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 143. ISBN 978-3-647-31086-2.

- ^ Kruglov, Anatoly Agapeevich. (Belarus, 1983). Fundamentals of Scientific Atheism: “The highest form is Marxist–Leninist atheism. * It relies on a materialistic understanding, not only of Nature (which was typical of pre–Marxist atheism) but also of society. . . .”

- ^ Институт научного атеизма (Академия общественных наук) (1981). "Вопросы научного атеизма" (in Russian). Изд-во "Мысл".

марксистско-ленинский атеизм всем своим содержанием «аправлен на развитие способностей личности. Религия лишает человека его собственного «я», раздваивает сознание, создает для него условия ...

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ In Novaya Zhizn No. 28, 3 December 1905, Marxists Internet Archive, Lenin said that: “Religion is one of the forms of spiritual oppression, which everywhere weighs down heavily upon the masses of the people, over-burdened by their perpetual work for others, by want and isolation . . . Those who toil and live in want all their lives are taught, by religion, to be submissive and patient while here on Earth, and to take comfort in the hope of a heavenly reward. . . . Religion is opium for the people. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze, in which the slaves of capital drown their human image, their demand for a life more or less worthy of Man.” Marxists Internet Archive

- ^ Thrower, James (1983). Marxist-Leninist "Scientific Atheism" and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9789027930606.

As an integral part of the Marxist–Leninist world-view, 'scientific atheism' is grounded in the view of the world and of Man enshrined in dialectical [materialism] and historical materialism: The study of scientific atheism brings to light an integral part of the Marxist–Leninist world-view. Being a philosophical science, scientific atheism emanates from the basic tenets of dialectical and historical materialism, both in explaining the origin of religion, and its scientific criticism of [religion]. (ibid., p. 272.)

- ^ Slovak Studies, Volume 21. The Slovak Institute in North America. p. 231. "The origin of Marxist–Leninist atheism, as understood in the USSR, is linked with the development of the German philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach."

- ^ a b De James Thrower (1983). Marxist-Leninist Scientific Atheism and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter. p. 135. ISBN 978-90-279-3060-6.

- ^ Yang, Fenggang (2012). Religion in China: Survival and Revival Under Communist Rule. Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-19-973564-8.

In the ideological lexicon of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Marxist-Leninist atheism is a fundamental doctrine.

- ^ Richard L. Rubenstein, John K. Roth (1988). The Politics of Latin American Liberation Theology. Washington Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-88702-040-7.

There were, however, Marxist voices that pointed out the disadvantages of such antireligious policies.

- ^ Hegel, G.W.F., Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821), Vorrede: Was vernünftig ist, das ist Wirklich; und was wirklich ist, das ist vernünftig. ["What is rational is real; and what is real is rational."]

- ^ Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Feuerbach, Ludwig. Essence of Christianity, New York: Harper Torch Books, 1957. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Feuerbach, Ludwig. Essence of Christianity, New York: Harper Torch Books, 1957. p. 152.

- ^ Feuerbach, Ludwig (1841). "Chapter XVI. The Distinction between Christianity and Heathenism". The Essence of Christianity. Translated by Eliot, George – via marxists.org.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 11. “. . . religious commitments should be intellectually and emotionally destroyed. . . . The catharsis of an intensive hatred towards the old God. . . . All previous religious institutions should be ruthlessly eradicated from the face of the Earth and from the memory of coming generations, so that they could never regain power over people's minds through deception and the promotion of fear from the mystical forces of the Heaven.”

- ^ a b c Pospielovsky, Dimitry V (29 September 1987). History Of Marxist-Leninist Atheism And Soviet Antireligious: A History Of Soviet Atheism In Theory And Practice And The Believer. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781349188383.

... old churches as Houses of the Lord should be demolished without any regret or mercy. As a materialist he believed that religious 'deceptions' were not worthy of any compromise or tolerance. They had to be destroyed. ... Feurbach insisted that the liberation of intrinsic human dignity from the reign of illusory images by the human mind in the form of religious beliefs could be achieved only if traditional faith as mercilessly attacked by a more decent and humanizing intellectual system. Religious commitments should be intellectually and emotionally destroyed by the catharsis of an intensive hatred of the old God. All previous religious institutions should be ruthlessly eradicated from the face of the earth and from the memory of coming generations, so that they could never regain power over people's minds through deception and the promotion of fear from the mystical forces of the Heavens. At this point young Marx was completely fascinated by Feuerbach's open rebellion against the powerful tradition of Christianity unconditionally as an intellectual revelation.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 13. “It was obvious at this point that reading Feuerhach was not the only source of inspiration for [Karl] Marx’s atheism. The fascination with Feuerbach’s war against Christianity was, for young Marx, nothing more than an expression of his own readiness to pursue, in an anti-religious struggle, all the social and political extremes that materialistic determination required in principle. Yet, as David Aikman, in his most profound and erudite study of Marx and Marxism, notes, the clue to Marx’s passionate and violent atheism, or rather [his] anti-theism, cannot be found in an intellectual tradition, alone. He traces Marx’s anti-theism to the young Marx’s preoccupation with the Promethean cult of ‘Satan as a destroyer’.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 11. “At this point young Marx was completely fascinated by Feuerbach’s ‘humanistic zest’, and he adopted Feuerbach’s open rebellion against the powerful tradition of Christianity, unconditionally, as an intellectual revelation. Very early in his career, Marx bought the seductive idea that the higher goals of humanity would justify any radicalism, not only the intellectual kind but the social and political as well.”

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol. 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 12. “Obviously Marx began his own theory of reality with an incomplete intellectual disdain for everything that religious thought, represented, theoretically, practically or emotionally. The cultural contributions of religion over the centuries were dismissed as unimportant and irrelevant to the well-being of the human mind."

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) pg 12. "The cultural contributions of religion over the centuries were dismissed as unimportant and irrelevant to the well-being of the human mind."

- ^ Marx, K.H. 1976. Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Collected Works, vol. 3. New York.

- ^ Karl Marx. "On the Jewish Question".

- ^ Karl Marx. "A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right: Introduction", December 1843 – January 1844, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, 7 and 10 February 1844.

- ^ Karl Marx. "Private Property and Communism".

- ^ Karl Marx. "Theses on Feuerbach". Archived 24 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1932) [1845–6]. "Part I: Feuerbach: Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook. A: Idealism and Materialism". The German Ideology. Marx-Engels Institute, Moscow – via marxists.org.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, Volume 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 23. "It [religion] had been taken over, however, by the ruling classes, says Marx, and gradually [it was] turned into a tool for the intellectual and emotional control of the masses. Marx insists on perceiving the history of Christianity as an enterprise for the preservation of the status quo, as an elaborate [...]."

- ^ Anti-Dühring, Friedrich Engels, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/ch27.htm

- ^ Pospielovsky. Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) pp. 16–17.

- ^ Friedrich Engels, Anti-Dühring, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/index.htm

- ^ Friedrich Engels, Anti-Dühring, 1,13, Negation of a Negation, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/index.htm

- ^ a b Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (13 May 1909). "The Attitude of the Workers' Party to Religion". Proletary – via marxists.org.

- ^ Lenin, V.I. (1965) [1905]. "Socialism and Religion". Lenin Collected Works. Vol. 10. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 83–87 – via www.marxists.org.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 18–19.

- ^ Richard Felix Staar. Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe. The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford University.

By 1976 all places of worship had been closed. However, the regime has had to admit that religion still maintains a following among Albanians. In order to suppress religious life, the following article has been included in the 1976 constitution: "The state recognizes no religion and supports and carries out atheistic propaganda to implant the scientific materialistic world outlook in people" (Article 37). In its antireligious moves, the regime has gone so far as to order persons to change their names if they are of a religious origin.

- ^ a b c d e Pospielovsky, Dimitry (1987). A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Antireligious Policies. Macmillan Publishers. p. 18-20. ISBN 9780312381325.

The third major person who contributed profoundly to the shaping of modern Communist ideology in the USSR was Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Lenin's chief source of philosophical education was the writings of Marx and Engels. His views, however, evolved in the unique cultural context of Russia and hence they were substantially influenced by the intellectual traditions of that country. As far as atheism is concerned Lenin made it the immediate political task of the party. ... Lenin believed atheistic propaganda to be an urgent necessity. ... Convinced of the fundamental argument of militant materialism, Lenin went far beyond the Russian tradition of political theism of Belinsky, Herzen and Pisarev and became the proponent of a systematic, aggressive and uncompromising movement of atheistic agitation, organized and fully supported by the party. He became the founder of a whole institution of professional atheistic propagandists, who spread all over the country after the revolution and played a very important role in the attack on the churches and the conversion of the faithful to the beliefs of the 'science-based materialistic world-view' of the communists. Lenin's unequivocally hostile attitude toward religion grew into a distinctive feature of the Bolshevik version of atheism. Compared with much milder views popular within the Social Democratic Party for example, Bolshevik atheism allowed for no compromise whatsoever with widely held religious views and sentiments even if this meant alienating some of the sympathetic, leftist-minded yet religious believing intellectuals, workers or peasants. ... In it he proclaimed that although traditional religion was conceptually wrong and ideologically biased towards the interests of the exploiting classes, it still cultivated in the masses emotion, moral values, desire which revolutionaries should take over and manipulate. ... He considered Lunacharsky's position harmful in the extreme, since according to Lenin, it dissolved Marxism into a mild liberal reformism. He thought that this position obscured the fact that the Church is the servant to the state, that religion all along has been a tool of ideological suppression of the masses. Lenin tried to expose the god-building programme as a dangerous and totally unnecessary programme as a dangerous and totally unnecessary compromise with the most reactionary forces in the Russian empire. Under the circumstances, he appealed to militant atheism as a criterion for the sincerity of Marxist commitments as a testing principle. ... So Lenin refused to allow for any compromise in the theoretical heritage of Marxism. He had the exammple of Marx's earlier rejection of Feuerbach's proposals for a religion of humanity, but in addition he had the conviction that under the confrontation of intense political pressures even the slightest deviation from the principles of materialism and atheism could degenerate into a betrayal of the cause of Communism altogether.

- ^ Simon, Gerhard. Church, State, and Opposition in the U.S.S.R., University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles (1974) p. 64. “The political situation of the Russian Orthodox Church, and of all other religious groups, in the Soviet Union is governed by two principles, which are logically contradictory. On the one hand, the Soviet Constitution of 5 December 1936, Article 124, guarantees ‘freedom to hold religious services’. On the other hand, the Communist Party has never made any secret of the fact, either before or after 1917, that it regards ‘militant atheism’ as an integral part of its ideology, and will regard ‘religion as by no means a private matter’. It therefore uses ‘the means of ideological influence to educate people in the spirit of scientific materialism and to overcome religious prejudices. . . .’ Thus, it is the goal of the C.P.S.U. and thereby also of the Soviet state, for which it is, after all, the ‘guiding cell’, gradually to liquidate the religious communities.”

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry V. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol. 1: A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti–Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 34.

- ^ Thrower, James. Marxist–Leninist ‘Scientific Atheism’ and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the U. S. S. R., Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin (1983) p. 118. “Many of the previous — and often tactical — restraints upon the [Communist] Party’s anti-religious stance disappeared, and, as time went by, the distinction, which Lenin had earlier drawn, between the attitude of the Party and the attitude of the State toward religion, became meaningless as the structures of the Party and the structures of the State increasingly began to coincide. Whilst the original constitution of the Russian Federal Republic guaranteed freedom of conscience, and included the right to both religious and anti-religious propaganda, this, in reality, meant freedom from religion — as was evidence when the decree proclaiming the new constitution forbade all private religious instruction for children under the age of eighteen, and when, shortly afterwards, Lenin ordered all religious literature, which had been previously published — along with all pornographic literature, to be destroyed. Eventually — in the Stalin constitution of 1936 — the provision for religious propaganda, other than religious worship, was withdrawn.”

- ^ Hyde, Douglas Arnold. Communism Today, University of Notre Dame Press, South Bend (1973) p. 74. “The conscious rejection of religion is necessary in order for communism to be established.”

- ^ Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol. 1: A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 8.

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1972) [1922]. "On the Significance of Militant Materialism". Lenin's Collected Works. Vol. 33. Translated by David Skvirsky; George Hanna. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 227–236 – via marxists.org.

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed. (1992). Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780521022309.

- ^ Ramet (1992), p. 15.

- ^ George Ginsburgs, William B. Simons (1994). Law in Eastern Europe. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 12.

Just as outrageous was the conduct of the NKVD abroad on those occasions where it was afforded the opportunity to enlarge the geographical scope of its work. Thousands of political suspects and Lamaist priests were rounded up in Mongolia by the NKVD in concert with its local affiliate, executed on the spot or shipped off to the Soviet Union to be shot or die at hard labor in the mushrooming GULAG system.

- ^ Todd, Allan; Waller, Sally (19 May 2011). History for the IB Diploma: Origins and Development of Authoritarian and Single Party States. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780521189347.

By the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, nearly 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslims mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

- ^ Thrower, James (1983). Marxist-Leninist "scientific Atheism" and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9789027930606.

In 1959, a new course, entitled Osnovy nauchnogo ateizma (Fundamentals of Scientific Atheism) was introduced into the curriculum of all higher educational institutions, including universities. The course was originally voluntary, but owing to the paucity of student response it has, from 1964, been compulsory for all students.

Further reading

[edit]- Husband, William. "Godless communists": atheism and society in Soviet Russia, 1917-1932 Northern Illinois University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-87580-595-7.

- Marsh, Christopher. Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Revival. Continuum International Publishing Group. 2011. ISBN 1-4411-1247-2.

- Pospielovsky, Dimitry. A History of Marxist–Leninist atheism and Soviet antireligious policies. Macmillan. 1987. ISBN 0-333-42326-7.

- Thrower, James. Marxist–Leninist scientific atheism and the study of religion and atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter. 1983. ISBN 90-279-3060-0.

External links

[edit]- Theomachy of Leninism - Православие.Ru

- Marxist-Leninist Scientific Atheism - Thomas J. Blakeley

- Марксисткий теизм:Атеизм основоположников марксизма (in Russian)

- University of Cambridge: Marxist–Leninist atheism

- Militant Atheist Objects: Anti-Religion Museums in the Soviet Union (Present Pasts, Vol. 1, 2009, 61-76, doi:10.5334/pp.13)