User:Joel Garvey/Burgundian Wars

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit]| Burgundian Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

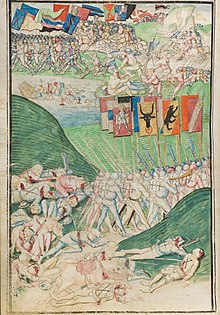

The battle of Morat, from Diebold Schilling's Berne Chronicle | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

The Burgundian Wars (1474–1477) were a conflict between the Burgundian State and the Old Swiss Confederacy and its allies. Open war broke out in 1474, and the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, was defeated three times on the battlefield in the following years and was killed at the Battle of Nancy in 1477. The Duchy of Burgundy and several other Burgundian lands then became part of France, and the Burgundian Netherlands and Franche-Comté were inherited by Charles's daughter Mary of Burgundy and eventually passed to the House of Habsburg upon her death because of her marriage to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Article body

[edit]Background[edit]

[edit]

The dukes of Burgundy had succeeded, over a period of about 100 years, in establishing their rule as a formidable force between the Holy Roman Empire and France. The consolidation of regional principalities with varying wealth into the Burgundian State brought great economic opportunity and wealth to the new power. In fact, a deciding factor for many elites in consolidating their lands was the relatively safe guarantee of making a profit under the economically stable Duchy of Burgundy.[1] Their possessions included, besides their original territories of the Franche-Comté and the Duchy of Burgundy, the economically strong regions of Flanders and Brabant as well as Luxembourg.

The dukes of Burgundy generally pursued aggressive expansionist politics, especially in Alsace and Lorraine, seeking to unite their northern and southern possessions geographically.[2] Having already been in conflict with the French king (Burgundy had sided with the English in the Hundred Years' War but then the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses, when Henry VI sided with France). This conflict had left the regional powers of France and England in a weakened state allowing for the rise of the Burgundian power alongside its fierce French rivals.[3] The repercussions of the Black Death also continued to affect Europe and assisted in maintaining a diminished society It is important to recognize in this context the agents which were driving this impressive military economy for the Burgundians which also might help explain their ability to continue warfare with enemies on all sides of the Burgundian borders. According to some historians, the extremely profitable region of the Low Countries supplied the Duchy of Burgundy with sufficient funds to support their ambitions internally, but especially externally.[4] In this period of expansion, treaties of trade and peace were signed oddly enough with Swiss cantons, a treaty that would benefit the security of each power against Habsburg and French ambitions.[5] Charles's advances along the Rhine brought him into conflict with the Habsburgs, especially Emperor Frederick III.

East of Burgundy, the blossoms of war began to appear as Burgundy pressed its influence over its Swiss neighbors. The Swiss Confederation had been in frequent conflict with the Turks for decades leading up to the 1470's due to papal calls for a crusade against the Turkic people. The idea of the teutshe nation (German nation) was used as a unifying force. According to a Cambridge publication on Swiss history, both the Swiss and Burgundians had made aggression a significant impact on the region's foreign affairs. In the effort of consolidated the Swiss confederacy and independence from Habsburg rule, Swiss forces gained control of the Hapsburg town Thurgau in an effort to expand its borders and influence.[6] The Bernese people were more frequently being attacked by Charles the Bold's Lombard mercenaries. This raised concern to Bern as they began to call on their Swiss allies for assistance in the conflict with Burgundy. The aggressive actions of Charles the Bold would eventually culminate in the Swiss giving him the nickname, "the Turk in the West" and making Burgundy as fierce a rival as the Turks in the East.

Conflict[edit]

[edit]Initially in 1469, Duke Sigismund of Habsburg of Austria pawned his possessions in the Alsace in the Treaty of Saint-Omer as a fiefdom to the Duke of Burgundy for a loan or sum of 50,000 florins, as well as an alliance with Charles the Bold, in order to have them better protected from the expansion of the Eidgenossen (or Old Swiss Confederacy). Charles' involvement west of the Rhine gave him no reason to attack the confederates, as Sigismund had wanted, but his embargo politics against the cities of Basel, Strasbourg and Mulhouse, directed by his reeve Peter von Hagenbach, prompted these to turn to Bern for help. Charles' expansionist strategy suffered a first setback in his politics when his attack on the Archbishopric of Cologne failed after the unsuccessful Siege of Neuss (1474–75).

In the second phase, Sigismund sought to achieve a peace agreement with the Swiss confederates, which eventually was concluded in Konstanz in 1474 (later called the Ewige Richtung or Perpetual Accord). He wanted to buy back his Alsace possessions from Charles, who refused. Shortly afterwards, von Hagenbach was captured and executed by decapitation in Alsace, and the Swiss, united with the Alsace cities and Sigismund of Habsburg in an anti-Burgundian league, conquered part of the Burgundian Jura (Franche-Comté) when they won the Battle of Héricourt in November 1474. Louis XI of France joined the coalition by the Treaty of Andernach in December. The next year, Bernese forces conquered and ravaged Vaud, which belonged to the Duchy of Savoy, who was allied with Charles the Bold. Bern had previously called out to its Swiss allies for expansion into the Vaud region of Savoy to prevent future aggression by Charles near Bernese lands which were geographically closest to Burgundy when compared to the rest of the Swiss Confederation. However, the other Swiss cities had become displeased at the ever-growing expansionist and aggressive Bernese foreign policy and as a result did not support Bern initially. The Confederacy was a collective defense agreement between the Swiss members and ensured that if one city were attacked, the others would come to its aid. Because the military actions by Bern in Savoy were an invasion, other Confederacy members had no legal obligation to come to the aid of their Bernese allies.

In the Valais, the independent republics of the Sieben Zenden, with the help of Bernese and other confederate forces, drove the Savoyards out of the lower Valais after a victory in the Battle on the Planta in November 1475. In 1476, Charles retaliated and marched to Grandson, which belonged to Pierre de Romont of Savoy but had recently been taken by the Swiss, where he had the garrison hanged or drowned in the lake, despite its capitulation.[7] When the Swiss confederate forces arrived a few days later, he was defeated in the Battle of Grandson and was forced to flee the battlefield, leaving behind his artillery and many provisions and valuables. Having rallied his army, he was dealt a devastating blow by the confederates at the Battle of Morat. As losses on the Burgundian side continued, Charles the Bold lost the support of his Lords who were losing men and profit and a rebellion soon began led by René II, Duke of Lorraine. As the revolt continued, Rene II used his land's strategic location between North and South Burgundy to cut off communication and disrupt war capabilities.[8] The internal conflict only made the war with the Swiss more difficult and, as a result, pulled Charles' attention away from the Confederacy to deal with the more pressing matter in René's revolt. Charles the Bold raised a new army, but fell in the Battle of Nancy in 1477 in which the Swiss fought alongside an army of René II. The military failures of Charles the Bold are summarized by a common contemporary Swiss quote, "Charles the Bold lost his goods at Grandson, his bravery at Morat, and his blood at Nancy".

It is important to note that the conflict did not simply involve two sides against each other, but also external powers with their own political interests. Near the end of 1476, the Swiss Confederacy began receiving orders from Pope Sixtus IV calling for an end of the war and a signing of peace between the Swiss and Charles.[9] Although this seemed to be a peaceful resolution to the war, the Pope's aspirations of Charles diverting his attention away from the Swiss and onto the Muslims in a crusade begin to show the Pope's true intentions when calling for peace. This papal pressure was eventually ignored by the Swiss who would only end the war under the conditions that Charles leaves the Duchy of Lorraine, lands controlled by René II. It is evident through contemporary writings that espionage and censorship played an influential role in Swiss and Burgundian actions throughout the war. Professional spies were hired on either side to recover information of enemy movements and weak points. However, this profession proved to be extremely lethal as some Swiss cities suffered heavy losses and attaining information of the opposing side continued to be a difficult task throughout the war.[10]

The Burgundian Wars also assisted in the shift of military strategy across Europe following the Swiss victories over the numerically superior Burgundians. The Gewalthaufen proved to be an effective Swiss military strategy against the superior Burgundian forces. Until this point, battles had been dominated by cavalry which could easily overpower infantry troops on the battlefield. However, the Gewalthaufen tactic used long spears to counter and defend against calvary with remarkable success. The Gewalthaufen marked a key shift in military history and tipped the balance in favor of infantry troops over mounted soldiers.[5]

Aftermath[edit]

[edit]

The results of this conflict proved to have significant repercussions for the future of the Duchy of Burgundy and the regional stability of Western Europe. With the death of Charles the Bold, the Valois dynasty of the dukes of Burgundy died out and widespread revolts engulfed the Duchy which soon collapsed under these pressures. The northern territories of the dukes of Burgundy became a possession of the Habsburgs, when Archduke Maximilian of Austria, who would later become Holy Roman Emperor, married Charles's only daughter, Mary of Burgundy. The duchy proper reverted to the crown of France under king Louis XI. The Franche-Comté initially also became French but was ceded to Maximilian's son Philip in 1493 by Charles VIII at the Treaty of Senlis in an attempt to bribe the emperor to remain neutral during Charles's planned invasion of Italy.

The victories of the Eidgenossen (Swiss Confederation) over what was one of the most powerful military forces in Europe gained it a reputation of being nearly invincible, and the Burgundian Wars marked the beginning of the rise of Swiss mercenaries on the battlefields of Europe.[5] Although Bern and other Swiss cities invaded and controlled large swathes of Savoyard territories, the Confederacy only maintained Grandson, Morat, and Echallens as notable cities. Inside the Confederacy itself, however, the outcome of the war led to internal conflict; the city cantons insisted on having the lion's share of the proceeds since they had supplied the most troops. The country cantons resented that, and the Dreizehn Orte disputes almost led to war. They were settled by the Stanser Verkommnis of 1481.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Beck, Sanderson. "France in the Renaissance 1453–1517". san.beck.org.

- ^ Stein, Robert (2017). Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-875710-8.

- ^ Housley, Norman (2004). Crusading in the Fifteenth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 70–94. ISBN 1-4039-0283-6.

- ^ Aberth, John (2001). From the Brink of the Apocalypse. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92715-3.

- ^ Blockmans, Wim (1999). The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1382-3.

- ^ a b c Marti, Susan (2009). Splendour of the Burgundian Court. Mercatorfonds. pp. 318–328. ISBN 978-0-8014-4853-9.

- ^ a b Church, Clive (2013). A concise history of switzerland. cambridge. pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-0-521-14382-0.

- ^ Vaughan, Richard (1973). Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. London: Longman Group Limited. ISBN 0 582 50251 9.

- ^ Cope, Christopher (1987). The Lost Kingdom of Burgundy. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. p. 180. ISBN 0-396-08955-0.

- ^ Aotani, Hideki (2014). The Papal Indulgence as a Medium of Communication in the Conflict between Charles the Bold and Ghent, 1467-69. Rome: Viella. pp. 231–249. ISBN 9788867282661.

- ^ Curry, Anne (2011). Journal of Medieval Military History. Rochester: The Boydell Press. pp. 76–131. ISBN 978 1 84383 668 1.