User:Goatmanatee/Manila galleon

The article could be reorganized. The section titled "Spice Trade" discusses a trade route oriented around silver, not spice, and cover more than trade, such as the construction of ships. It could possibly be combined with the previous section in a larger section titled "History," broken down into subsections.

The article could also do more to emphasize the economy that sprang up to supply the voyage, such as mule trains, agriculture, inn keepers, and dock workers.

The article was neutrally written, but places more emphasis on the discovery of the route than the route itself.

Organization

[edit]Lead

1 - History

1.1 - Discovery of the route

1.2 - The Manila Galleon and California

1.3 - Trade

1.4 - End of the Galleons

2 - Galleons

2.1 - Construction

2.2 - Crews

3 - Possible contact with Hawaii

4 - Preparations for UNESCO nominations

History

[edit]Discovery of the route

[edit]

In 1521, a Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan sailed west across the Pacific using the westward trade winds. The expedition discovered the Mariana Islands and the Philippines and claimed them for Spain. Although Magellan died there, one of his ships, the Victoria, made it back to Spain by continuing westward.

In order to settle and trade with these islands from the Americas, an eastward maritime return path was necessary. The first ship to try this a few years later failed. In 1529, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón also tried sailing east from the Philippines, but could not find the eastward winds across the Pacific. In 1543, Bernardo de la Torre also failed. In 1542, however, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo helped pave the way by sailing north from Mexico to explore the Pacific coast, reaching as far north as the Russian River, just north of the 38th parallel. The frustration of these failures is shown in a letter sent in 1552 from Portuguese Goa by the Spanish missionary Francis Xavier to Simão Rodrigues asking that no more fleets attempt the New Spain-East Asia route, lest they are lost.[1]

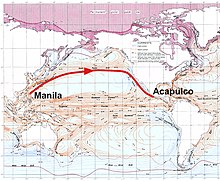

The Manila-Acapulco galleon trade finally began when Spanish navigators Alonso de Arellano and Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the eastward return route in 1565. Sailing as part of the expedition commanded by Miguel López de Legazpi to conquer the Philippines in 1565, Arellano and Urdaneta were given the task of finding a return route. Reasoning that the trade winds of the Pacific might move in a gyre as the Atlantic winds did, they had to sail north to the 38th parallel north, off the east coast of Japan, before catching the eastward-blowing winds ("westerlies") that would take them back across the Pacific.

Reaching the west coast of North America, Urdaneta's ship the San Pedro hit the coast near Cape Mendocino, California, then followed the coast south to San Blas and later to Acapulco, arriving on October 8, 1565.[2] Most of his crew died on the long initial voyage, for which they had not sufficiently provisioned. Arellano, who had taken a more southerly route, had already arrived.

The English privateer Francis Drake also reached the California coast, in 1579. After capturing a Spanish ship heading for Manila, Drake turned north, hoping to meet another Spanish treasure ship coming south on its return from Manila to Acapulco. He failed in that regard, but staked an English claim somewhere on the northern California coast. Although the ship's log and other records were lost, the officially accepted location is now called Drakes Bay, on Point Reyes south of Cape Mendocino.[a][11]

By the 18th century, it was understood that a less northerly track was sufficient when nearing the North American coast, and galleon navigators steered well clear of the rocky and often fogbound northern and central California coast. According to historian William Lytle Schurz, "They generally made their landfall well down the coast, somewhere between Point Conception and Cape San Lucas ... After all, these were preeminently merchant ships, and the business of exploration lay outside their field, though chance discoveries were welcomed".[12]

The first motivation for land exploration of present-day California was to scout out possible way-stations for the seaworn Manila galleons on the last leg of their journey. Early proposals came to little, but in 1769, the Portola expedition established ports at San Diego and Monterey (which became the administrative center of Alta California), providing safe harbors for returning Manila galleons.

The Manila Galleon and California

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

Monterey, California was about two months and three weeks out from Manila in the 18th century, and the galleon tended to stop there 40 days before arriving in Acapulco. Galleons stopped in Monterey prior to California's settlement by the Spanish in 1769; however visits become regular between 1777 and 1794 because the Crown ordered the galleon to stop in Monterey.

Trade

[edit]

Trade with Ming China via Manila served a major source of revenue for the Spanish Empire and as a fundamental source of income for Spanish colonists in the Philippine Islands. Galleons used for the trade between East and West were crafted by Filipino artisans.[13] Until 1593, two or more ships would set sail annually from each port.[14] The Manila trade became so lucrative that Seville merchants petitioned king Philip II of Spain to protect the monopoly of the Casa de Contratación based in Seville. This led to the passing of a decree in 1593 that set a limit of two ships sailing each year from either port, with one kept in reserve in Acapulco and one in Manila. An "armada" or armed escort of galleons, was also approved. Due to official attempts at controlling the galleon trade, contraband and understating of ships' cargo became widespread.[15]

The galleon trade was supplied by merchants largely from port areas of Fujian who traveled to Manila to sell the Spaniards spices, porcelain, ivory, lacquerware, processed silk cloth and other valuable commodities. Cargoes varied from one voyage to another but often included goods from all over Asia - jade, wax, gunpowder and silk from China; amber, cotton and rugs from India; spices from Indonesia and Malaysia; and a variety of goods from Japan, the Spanish part of the so-called Namban trade, including fans, chests, screens, porcelain and lacquerware.[16]

Galleons transported the goods to be sold in the Americas, namely in New Spain and Peru as well as in European markets. East Asia trading primarily functioned on a silver standard due to Ming China's use of silver ingots as a medium of exchange. As such, goods were mostly bought by silver mined from New Spain and Potosí.[15] In addition, slaves from various origins were transported from Manila.[17]

The cargoes arrived in Acapulco and were transported by land across Mexico. Mule trains would carry the goods along the China Road from Acapulco first to the administrative center of Mexico City, then on to the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were loaded onto the Spanish treasure fleet bound for Spain.[18] The transport of goods overland by porters, the housing of travelers and sailors at inns by innkeepers, and the stocking of long voyages with food and supplies provided by haciendas before departing Acapulco helped to stimulate the economy of New Spain.[18]

Around 80% of the goods shipped back from Acapulco to Manila were from the Americas - silver, cochineal, seeds, sweet potato, tobacco, chickpea, chocolate and cocoa, watermelon,[citation needed] vine and fig trees. The remaining 20% were goods transshipped from Europe and North Africa such as wine and olive oil, and metal goods such as weapons, knobs and spurs.[16]

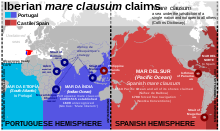

This Pacific route was the alternative to the trip west across the Indian Ocean, and around the Cape of Good Hope, which was reserved to Portugal according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. It also avoided stopping over at ports controlled by competing powers, such as Portugal and the Netherlands. From the early days of exploration, the Spanish knew that the American continent was much narrower across the Panamanian isthmus than across Mexico. They tried to establish a regular land crossing there, but the thick jungle and malaria made it impractical.

It took at least four months to sail across the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco, and the galleons were the main link between the Philippines and the viceregal capital at Mexico City and thence to Spain itself. Many of the so-called "Kastilas" or Spaniards in the Philippines were actually of Mexican descent, and the Hispanic culture of the Philippines is somewhat close to Mexican culture.[19] Soldiers and settlers recruited from Mexico and Peru were also gathered in Acapulco before they were sent to settle at the presidios of the Philippines.[20] Even after the galleon era, and at the time when Mexico finally gained its independence, the two nations still continued to trade, except for a brief lull during the Spanish–American War.

In Manila, the safety of ocean crossings was commended to the virgin Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga in masses held by the Archbishop of Manila. If the expedition was successful the voyagers would go to the La Ermita (church) to pay homage, and offer gold and other precious gems or jewelries from Hispanic countries, to the image of the virgin. So it came to be that the Virgin was named the "Queen of the Galleons".

End of the Galleons

[edit]In 1740, as part of the administrative changes of the Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown began allowing the use of registered ships or navíos de registro in the Pacific that traveled solo outside of the convoy system of the galleons.[21] While these solo voyages would not immediately replace the galleon system, they were more efficient and better able to avoid the British navy.[21]

The Manila-Acapulco galleon trade ended in 1815, a few years before Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. After this, the Spanish Crown took direct control of the Philippines, and governed directly from Madrid. Sea transport became easier in the mid-19th century upon the invention of steam power ships and the opening of the Suez Canal, which reduced the travel time from Spain to the Philippines to 40 days.

Galleons

[edit]Construction

[edit]

Between 1609 and 1616, 9 galleons and 6 galleys were constructed in Philippine shipyards. The average cost was 78,000 pesos per galleon and at least 2,000 trees. The galleons constructed included the San Juan Bautista, San Marcos, Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, Angel de la Guardia, San Felipe, Santiago, Salbador, Espiritu Santo, and San Miguel. "From 1729 to 1739, the main purpose of the Cavite shipyard was the construction and outfitting of the galleons for the Manila to Acapulco trade run."[22]

Due to the route's high profitability but long voyage time, it was essential to build the largest possible galleons, which were the largest class of European ships known to have been built until then.[23][24] In the 16th century, they averaged from 1,700 to 2,000 tons, were built of Philippine hardwoods and could carry 300 - 500 passengers. The Concepción, wrecked in 1638, was 43 to 49 m (141 to 161 ft) long and displacing some 2,000 tons. The Santísima Trinidad was 51.5 m long. Most of the ships were built in the Philippines and only eight in Mexico.

Crews

[edit]Sailors averaged age 28 or 29 while the oldest were between 40 and 50. Ships pages were children who entered service mostly at age 8, many orphans or poor taken from the streets of Seville, Mexico and Manila. Apprentices were older than the pages and if successful would be certified a sailor at age 20. Because mortality rates were high with ships arriving in Manila with a majority of their crew often dead from starvation, disease and scurvy, especially in the early years, Spanish officials in Manila found it difficult to find men to crew their ships to return to Acapulco. Many indios of Filipino and Southeast Asian origin made up the majority of the crew. Other crew were made up of deportees and criminals from Spain and the colonies. Many criminals were sentenced to serve as crew on royal ships. Less than a third of the crew was Spanish and they usually held key positions on board the galleon.[25]

At port, goods were unloaded by dockworkers, and food was often supplied locally. In Acapulco, the arrival of the galleons provided seasonal work, as for dockworkers who were typically free black men highly paid for their back breaking labor, and for farmers and haciendas across Mexico who helped stock the ships with food before voyages.[18] On land, travelers were often housed at inns or mesones, and had goods transported by muleteers, which provided opportunities for Indigenous people in Mexico.[18] By providing for the galleons, Spanish colonial America was tied into the broader global economy.[18]

Shipwrecks

[edit]The wrecks of the Manila galleons are legends second only to the wrecks of treasure ships in the Caribbean. In 1568, Miguel López de Legazpi's own ship, the San Pablo (300 tons), was the first Manila galleon to be wrecked en route to Mexico. Between the years 1576 when the Espiritu Santo was lost and 1798 when the San Cristobal (2) was lost there were twenty Manila galleons[26] wrecked within the Philippine archipelago. In 1596 the San Felipe was wrecked in Japan. The cargo was seized by the Japanese authorities and the behavior of the crew prompted persecution against the Christians.

At least one galleon, probably the Santo Cristo de Burgos, is believed to have wrecked on the coast of Oregon in 1693. Known as the Beeswax wreck, the event is described in the oral histories of the Tillamook and Clatsop, which suggest that some of the crew survived.[27][28][29]

Between 1565 and 1815 Spain owned 108 galleons, of which 26 were lost at sea for various reasons. Significant galleon captures by the British occurred in 1587 when the Santa Anna was captured by Thomas Cavendish, in 1709 with the Encarnacion, in 1743 when the Nuestra Senora de la Covadonga was taken by George Anson on his voyage around the world, and in 1762 with the Nuestra Senora de la Santisima Trinidad.[22]

- ^ Pereira Fernández, José Manuel (Third Quarter 2008). "Andrés de Urdaneta: In memoriam en el quinto centenario de su nacimiento" [Andrés de Urdaneta: In memoriam in the fifth centenary of his birthday] (PDF). Revista de Historia Naval (in Spanish) (102). Spain: Ministry of Defence (Spain): 16. ISSN 0212-467X. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

The letter is referenced as Rodríguez Rodríguez, I.; Álvarez Fernández, J. (1991). Andrés de Urdaneta, agustino. En carreta sobre el Pacífico [Andrés de Urdaneta, Augustinian. By cart over the Pacific] (in Spanish). Zamora. p. 181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Derek Hayes (2001). Historical atlas of the North Pacific Ocean: maps of discovery and scientific exploration, 1500–2000. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 18. ISBN 9781550548655.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "University of California Archaeological Site Survey Record, Mrn-230". Winepi.com. Archived from the original (DOC) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "A Brief History of Scholarship Relating to Drake's Port of Nova Albion". Winepi.com. Archived from the original (DOC) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Property Name: Drakes Bay Historic and Archeological District". Winepi.com. Archived from the original (DOC) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Landmarks Committee of the National Park System Advisory Board Meeting". Federal Register. 8 September 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Federal Register, Volume 76 Issue 189 (Thursday, September 29, 2011)". Govinfo.gov. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Interior Designates 27 New National Landmarks". Doi.gov. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "The Drake Navigators Guild Press Release". Winepi.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ Schurz 1917, p.107-108

- ^ https://www.rappler.com/move-ph/ispeak/96830-forgotten-history-polistas-galleon-trade

- ^ Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon, 1939. P 193.

- ^ a b Charles C. Mann (2011), 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, Random House Digital, pp. 123–163, ISBN 9780307596727

- ^ a b Mejia, Javier. "The Economics of the Manila Galleon". New York University, Abu Dhabi.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tatiana Seijas (23 June 2014). Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-95285-9.

Rose, Christopher (13 January 2016). "Episode 76: The Trans-Pacific Slave Trade". 15 Minute History. University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 13 January 2016. - ^ a b c d e Seijas, Tatiana (2016-01-02). "Inns, mules, and hardtack for the voyage: the local economy of the Manila Galleon in Mexico". Colonial Latin American Review. 25 (1): 56–76. doi:10.1080/10609164.2016.1180787. ISSN 1060-9164.

- ^ Guevarra, Rudy P. (2007). Mexipino: A History of Multiethnic Identity and the Formation of the Mexican and Filipino Communities of San Diego, 1900–1965. University of California, Santa Barbara. ISBN 0549122869

- ^ "Forced Migration in the Spanish Pacific World" By Eva Maria Mehl, page 235.

- ^ a b Burkholder, Mark A., 1943-. Colonial Latin America. Johnson, Lyman L., (Tenth edition ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-19-064240-2. OCLC 1015274908.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fish, Shirley (2011). The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific. AuthorHouse. pp. 128–130. ISBN 9781456775421.

- ^ See Chinese treasure ship for Chinese vessels that might have been larger.

- ^ Crown, trade, church and indigenous societies: The functioning of the Spanish shipbuilding industry in the Philippines, 1571-1816. By Ivan Valdez-Bubnov, Page 571

- ^ Leon-Guerrero, Jillette. "Manila Galleon Crew Members". Guampedia. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-01-10. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Williams, Scott S. (2016). "Chapter 8: The Beeswax Wreck, A Manila Galleon in Oregon, USA". In Wu, Chunming (ed.). Early Navigation in the Asia-Pacific Region: A Maritime Archaeological Perspective. Springer. pp. 146–168. ISBN 978-981-10-0904-4. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ La Follette, Cameron; Deur, Douglas (July 2018). "Views Across the Pacific: The Galleon Trade and Its Traces in Oregon". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 119 (2). Oregon Historical Society: 160–191. doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.119.2.0160. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ La Follette, Cameron; Deur, Douglas; Griffin, Dennis; Williams, Scott S. (July 2018). "Oregon's Manila Galleon". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 119 (2). Oregon Historical Society: 150–159. doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.119.2.0150.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).