User:Blackknight12/sandbox

| History of Sri Lanka | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronicles | ||||||||||||||||

| Periods | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| By Topic | ||||||||||||||||

The history of Sri Lanka covers Sri Lanka and the history of the Indian subcontinent and its surrounding regions of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Prehistoric Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.[1] The earliest humans found in Sri Lanka date to Prehistoric times about 35,000 years ago. Little is known about the history before the Indo-Aryan Settlement in the 6th century BC. The earliest documents of the settlement on the Island and its early history are found in the national chronicles of the Mahāvamsa, Dipavamsa, and the Culavamsa.[2][3]

According to the Mahāvamsa, a chronicle written in Pāḷi, the preceeding inhabitants of Sri Lanka were said to be Yakkhas and Nagas.[4] Sinhalese history traditionally starts in 543 BC with the arrival of Prince Vijaya, a semi-legendary prince who sailed with 700 followers to the island, after being expelled from the Vanga Kingdom, in present-day Bengal.[5] Prince Vijaya thereafter established the Sinhala Kingdom ushering in the historical period of Sri Lanka. During the Anuradhapura period (377 BCE–1017) Buddhism was introduced in the 3rd century BCE by Mahinda, son of Indian emperor Ashoka.[6]

Due to the island's close proximity to Southern India, Dravidian influence on Sri Lankan politics and trade had been very active since the third century BC. Trade relations between the Anuradhapura Kingdom and southern India existed very probably from an early time.[7][8] South Indian attempts at usurping power of the Anuradhapura Kingdom appears to have been at least motivated by the prospect of influencing the country's lucrative external trade.[7] From about the fifth century AD onwards, Tamil mercenaries were brought to the island for the service of the Sinahalese monarchs.[7][9] This would play a small part in the fall of the Anuradhapura Kingdom in the 11th century with the Chola conquest.

Invasion of the Anuradhapura Kingdom by Rajaraja I began in 993 AD when he sent a large army to conquer the kingdom and absorb it into the Chola Empire.[10] By 1017 most of the island was conquered and incorporated as a province of the vast empire beginning the Polonnaruwa period (1017–1232) of Sri Lanka.[11][12][13] However the Chola occupation would be overthrown in 1070 through a campaign of Sinhalese Resistance led by Prince Kitti (later Vijayabahu I of Polonnaruwa).[14] From the 10th century more permanent settlements of Tamils began to appear in Sri Lanka. While not extensive, these settlements formed the nucleus for later settlements around that of Northern Sri Lanka which would later form the Sri Lankan Tamil community of today.[9]

The Sinhalese Kingdom now located in Polonnaruwa lasted less than two centuries. During its later turbulent stages it was once again invaded from the Indian mainland forcing the Sinhalese to abandon their tranditional center of administration in the North central region of the island and flee south into the mountainous interior. This invasion saw a catastrophic decline in Sinhalese power and began the Transitional period (1232–1597), which was characterised by the succession of capitals followed by the creation of the Jaffna Kingdom as a buffer state by the South Indian Pandyans.

The Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1521–1597), started with the Vijayabā Kollaya, the division of the Sinhalese Kingdom, now at Kotte. The country was divided among three brothers resulting in a series of Wars of Succession. It was also at this time that the Portuguese intruded into the internal affiars of Sri Lanka, establishing control over the maritime regions of the island and seeking to control its lucrative external trade. The Crisis culminated in the collapse of the short lived but influential Kingdom of Sitawaka, and with Portuguese dominance, if not control by 1597, over two of three kingdoms that had existed at the start of the century, including the Jaffna Kingdom.[15] The Kingdom of Kandy was the only independent Sinhalese kingdom to survive thus beginning the Kandyan period (1597–1815).[16]

The Portuguese lost their possessions in Sri Lanka due to Dutch intervention in the Eighty Years' War, and the Dutch too were soon replaced by the British. Following the Kandyan Wars and an internal struggle between the Sinhalese monarch at the time and the Kandyan aristocracy, the island was united for the final time and came under British colonial rule in 1815 beginning the British Ceylon period (1815–1948). Armed resistance against the British took place in the 1818 and the 1848. Native sovereignty was once again archieved when Independence was granted in 1948 as a Dominion of the British Empire. In 1972 Sri Lanka became a Republic. A constitution was introduced in 1978 which created Sri Lanka a unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic. In the 1970s and 80s the country suffered from armed uprisings in 1971 and 1987–89 and a Civil War which lasted 25 years ending in 2009.

Geographical background

[edit]Sri Lanka lies on the Indian Plate, a major tectonic plate that was formerly part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[17] It is in the Indian Ocean southwest of the Bay of Bengal, between latitudes 5° and 10°N, and longitudes 79° and 82°E.[18][19] Sri Lanka is separated from the mainland portion of the Indian subcontinent by the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait. According to Hindu mythology, a land bridge existed between the Indian mainland and Sri Lanka. It now amounts to only a chain of limestone shoals remaining above sea level.[20] Legends claim that it was passable on foot up to 1480 AD, until cyclones deepened the channel.[21][22] Portions are still as shallow as 1 metre (3 ft), hindering navigation.[23] The island consists mostly of flat to rolling coastal plains, with mountains rising only in the south-central part. The highest point is Pidurutalagala, reaching 2,524 metres (8,281 ft) above sea level.

Sri Lanka has 103 rivers. The longest of these is the Mahaweli River, extending 335 kilometres (208 mi).[24] These waterways give rise to 51 natural waterfalls of 10 meters or more. The highest is Bambarakanda Falls, with a height of 263 metres (863 ft).[25] Sri Lanka's coastline is 1,585 km long.[26] Sri Lanka claims an Exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles, which is approximately 6.7 times Sri Lanka's land area. The coastline and adjacent waters support highly productive marine ecosystems such as fringing coral reefs and shallow beds of coastal and estuarine seagrasses.[27]

Sri Lanka has 45 estuaries and 40 lagoons.[26] Sri Lanka's mangrove ecosystem spans over 7,000 hectares and played a vital role in buffering the force of the waves in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.[28] The island is rich in minerals such as ilmenite, feldspar, graphite, silica, kaolinite, mica and thorium.[29][30] Existence of petroleum and gas in the Gulf of Mannar has also been confirmed and the extraction of recoverable quantities is underway.[31]

Lying within the Indomalayan realm, Sri Lanka is one of 25 biodiversity hotspots in the world.[32] Although the country is relatively small in size, it has the highest biodiversity density in Asia.[33] A remarkably high proportion of the species among its flora and fauna, 27% of the 3,210 flowering plants and 22% of the mammals (see List), are endemic.[34] Sri Lanka has declared 24 wildlife reserves, which are home to a wide range of native species such as Asian elephants, leopards, sloth bears, the unique small loris, a variety of deer, the purple-faced langur, the endangered wild boar, porcupines and Indian pangolins.[35]

Flowering acacias flourish on the arid Jaffna Peninsula. Among the trees of the dry-land forests are valuable species such as satinwood, ebony, ironwood, mahogany and teak. The wet zone is a tropical evergreen forest with tall trees, broad foliage, and a dense undergrowth of vines and creepers. Subtropical evergreen forests resembling those of temperate climates flourish in the higher altitudes.[36] Yala National Park in the southeast protects herds of elephant, deer, and peacocks. The Wilpattu National Park in the northwest, the largest national park, preserves the habitats of many water birds such as storks, pelicans, ibis, and spoonbills. The island has four biosphere reserves: Bundala, Hurulu Forest Reserve, the Kanneliya-Dediyagala-Nakiyadeniya, and Sinharaja.[37] Of these, Sinharaja forest reserve is home to 26 endemic birds and 20 rainforest species, including the elusive red-faced malkoha, the green-billed coucal and the Sri Lanka blue magpie.

During the Mahaweli Development programme of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Sri Lanka, the government set aside four areas of land totalling 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi) as national parks. Sri Lanka's forest cover, which was around 49% in 1920, had fallen to approximately 24% by 2009.[38][39]

Overview

[edit]Periodization of Sri Lanka history:

| Dates | Period | Period | Span (years) | Subperiod | Span (years) | Main government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300,000 BP–~1000 BC | Prehistoric Sri Lanka | Stone Age | – | 300,000 | Unknown | |

| Bronze Age | – | |||||

| ~1000 BC–543 BC | Iron Age | – | 457 | |||

| 543 BC–437 BC | Ancient Sri Lanka | Pre-Anuradhapura | – | 106 | Monarchy | |

| 437 BC–463 AD | Anuradhapura | 1454 | Early Anuradhapura | 900 | ||

| 463–691 | Middle Anuradhapura | 228 | ||||

| 691–1017 | Post-classical Sri Lanka | Late Anuradhapura | 326 | |||

| 1017–1070 | Polonnaruwa | 215 | Chola conquest | 53 | ||

| 1055–1232 | 177 | |||||

| 1232–1341 | Transitional | 365 | Dambadeniya | 109 | ||

| 1341–1412 | Gampola | 71 | ||||

| 1412–1592 | Early Modern Sri Lanka | Kotte | 180 | |||

| 1592–1739 | Kandyan | 223 | 147 | |||

| 1739–1815 | Nayakkar | 76 | ||||

| 1815–1833 | Modern Sri Lanka | British Ceylon | 133 | Post-Kandyan | 18 | Colonial monarchy |

| 1833–1948 | 115 | |||||

| 1948–1972 | Contemporary Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka since 1948 | 76 | Dominion | 24 | Constitutional monarchy |

| 1972–present | Republic | 52 | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Prehistoric Sri Lanka

[edit]Pre Iron Age (Pre ~1000 BC)

[edit]The pre-history of Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.[1] The era spans the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and early Iron Ages. Among the Paleolithic human settlements discovered in Sri Lanka, Pahiyangala (named after the Chinese traveller monk Faxian), which dates back to 37,000 BP, Batadombalena (28,500 BP) and Belilena (12,000 BP) are the most important.[40][41] In these caves, archaeologists have found the remains of anatomically modern humans which they have named Balangoda Man, and other evidence suggesting that they may have engaged in agriculture and kept domestic dogs for driving game.[42][43]

One of the first written references to the island is found in the Indian epic Ramayana, which provides details of a kingdom named Lanka that was created by the divine sculptor Vishwakarma for Kubera, the Lord of Wealth.[44][45] It is said that Kubera was overthrown by his demon stepbrother Ravana, the powerful emperor who built a mythical flying machine named Dandu Monara.[46] The modern city of Wariyapola is described as Ravana's airport.[47]

Early inhabitants of Sri Lanka were probably ancestors of the Vedda people,[48] an indigenous people numbering approximately 2,500 living in modern-day Sri Lanka. The 19th-century Irish historian James Emerson Tennent theorized that Galle, a city in southern Sri Lanka, was the ancient seaport of Tarshish from which King Solomon is said to have drawn ivory, peacocks, and other valuables.

Iron Age (~1000 BC–543 BC)

[edit]The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1200 BCE, if not earlier[49][50] The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon-dated to c. 1000–800 BCE at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya.[51][52][53][54] It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.[55] Archaeological evidence for the beginnings of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka is found at Anuradhapura, where a large city–settlement was founded before 900 BCE. The settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE, but by 700 BCE it had expanded to 50 hectares.[56] A similar site from the same period has also been discovered near Aligala in Sigiriya.[57]

The hunter-gatherer people known as the Wanniyala-Aetto or Veddas, who still live in the central, Uva and north-eastern parts of the island, are probably direct descendants of the first inhabitants, Balangoda Man. They may have migrated to the island from the mainland around the time humans spread from Africa to the Indian subcontinent. Achievements include the construction of the largest reservoirs and dams of the ancient world as well as enormous pyramid-like stupa architecture. This phase of Sri Lankan culture may have seen the introduction of early Buddhism.[58] Early mythical history recorded in Buddhist scriptures refers to three visits by the Buddha to the island to see the Naga Kings, snakes that can take the form of a human at will.[59] The earliest surviving chronicles from the island, the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, say that tribes of Yakkhas, Nagas and Devas inhabited the island prior to the Indo-Aryan migration.

Pre-Anuradhapura period (543–437 BCE)

[edit]

The Pali chronicles, the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Thupavamsa and the Culavamsa, as well as a large collection of stone inscriptions, the Indian Epigraphical records, the Burmese versions of the chronicles etc., provide information on the history of Sri Lanka from about the 6th century BCE.[6]

According to the Mahāvamsa, a chronicle written in Pāḷi, the inhabitants of Sri Lanka prior to the Indo-Aryan migration were Yakkhas and Nagas.[60][61] Ancient grave sites that were used before 600 BC and other signs of civilisation have also been discovered in Sri Lanka, but little is known about the history of the island before this time.[62][63] Sinhalese history and the historical period of Sri Lanka traditionally starts in 543 BC with the arrival of Prince Vijaya, a semi-legendary prince who sailed with 700 followers to Sri Lanka.[64]

The Mahāvamsa tells of Sinhabahu, new King of Vanga, who gave up the throne and went back to his birthplace in Lala founding a city called Sinhapura (or Sihapura). He married his sister Sinhasivali. both of whom were decendants of the king of Vanga (present-day Bengal) and a princess of the neighbouring Kalinga (present-day Odisha). The couple had 32 sons in form of 16 pairs of twins. Vijaya was their eldest son, followed by his twin Sumitta.[65][66][5]

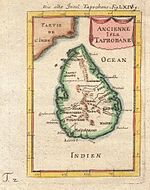

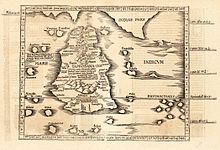

Vijaya was made the prince-regent by his father, but he and his band of followers became notorious for their violent deeds. After their repeated complaints failed to stop Vijaya's acts, the prominent citizens demanded that Vijaya be put to death. King Sinhabahu then decided to expel Vijaya and his 700 followers from the kingdom. The men's heads were half-shaved and they were put on a ship that was sent forth on the sea. The wives and children of these 700 men were also sent on separate ships. Vijaya had his followers landed at a place called Supparaka; the women landed at a place called Mahiladipaka, and the children landed at a place called Naggadipa. Vijaya's ship later reached Sri Lanka, on the North west coast of present-day Puttalam, on the same day Gautama Buddha died in northern India.[67][68][5] Vijaya's landing in Sri Lanka on the same day as the Buddha's death is likely to have been constructed so as to agree.[66][69] Upon touching the ground with their hands, their palms became reddened by the red soil on which they rested and thereafter named the land Tambapaṇṇī (meaning "copper-red hands"). The whole island would later be known by this name. It was by this name, Taprobane, that the Ancient Greeks would refer to the island by.[67] Those who believe that Vijaya set out from the west coast of India (Sinhapura being located in present-day Gujarat) identify the present-day Sopara as the location of Supparaka.[18] Those who believe that Sinhapura was located in Vanga-Kalinga region identify it with places located off the eastern coast of India.

Vijaya tied a protective (paritta) thread on the hands of all his followers. Later, a Yakkhini (a female Yakkha) appeared before Vijaya's followers in form of a dog. One of the followers thought that the presence of a dog indicated the existence of a habitation, and went chasing her. After following her for some time, he saw a Yakkhini named Kuveni (who was spinning thread. Kuveni tried to devour him, but Vijaya's magical thread protected him. Unable to kill him, Kuveni hurled the follower into a chasm. She did the same thing to all the 700 followers. Meanwhile, Vijaya came to Kuveni's place, looking for his men. Vijaya overpowered her, and forced her to free his men. Kuveni asked Vijaya to spare her life, and in return, swore loyalty to him. She brought, for Vijaya and his followers, food and goods from the ships of the traders whom she had devoured earlier. Vijaya took Kuveni as his consort.[70][71] It should be noted that there is no mention of Kuveni and the Yakkhas in the older Sinhalese chronicle the Dipavamsa.[72]

As Vijaya and Kuveni were sleeping, he woke up to sounds of music and singing. Kuveni informed him that the island was home to Yakkhas, who would kill her for giving shelter to Vijaya's men. She explained that the noise was because of wedding festivities in the Yakkha city of Sirisavatthu. With Kuveni's help, Vijaya defeated the Yakkhas. Vijaya and Kuveni had two children: Jivahatta and Disala. Vijaya established the Kingdom of Tambapanni. The new community established by him were now called Sinhala (සිංහල) after Sinhabahu.[73][74][71][75] And the island itself became to be known Sinhala-dipa; "the island of the Sinhalese". It is from this name that subsequent names for the island, i.e. Serendiva, Serendip, Ceilão, Zeilan, Ceylan, Ceylon were formed. To the Sinhalese the island would be always known as Lanka.[18]

Vijaya's ministers and other followers established several new villages. For example, Upatissa established Upatissagāma on the bank of the Gambhira river, north of Anuradhagama. His followers decided to formally consecrate him as king, but for this he needed a queen of the same rank, an Aryan (noble). Vijaya's ministers, therefore, sent emissaries with precious gifts to the city of Madhura, which was ruled by a Pandu king.[note 1] The king agreed to send his daughter as Vijaya's bride. He also requested other families to offer their daughters as brides for Vijaya's followers. Seven hundred daughters of the principal nobles came along with the Princess.[76] The Pandu king sent to Sri Lanka his own daughter, other women (including a hundred maidens of noble descent), craftsmen, a thousand families of 18 guilds, elephants, horses, waggons, and other gifts. This group landed in Sri Lanka, at a port known as Mahatittha.[77][71] Vijaya married the princess and was consecrated as King with great splendour. The other Pandu ladies were bestowed on the King's minister's, according to their grades, or castes. This is the first time in Sri Lankan history castes are mentioned. Though the system could have also come with Vijaya and his settlers.[78][71] Dipavamsa also omits mention of the South Indian princess.[79]

Vijaya then requested Kuveni, his Yakkhini queen, to leave the community, saying that his citizens feared supernatural beings like her. He offered her money, and asked her to leave their two children, Jivahatta and Disala, behind. But Kuveni took the children along with her to the Yakkha city of Lankapura. She asked her children to stay back, as she entered the city, where other Yakkhas recognized her as a traitor. She was suspected of being a spy, and was killed by a Yakkha. On advice of her maternal uncle, the children fled to Sumanakuta (identified with Sri Pada). In the Malaya region of Sri Lanka, they became husband-wife and gave rise to the Pulinda race (identified with the Vedda people).[note 2][80][71] The Vedda however are probably with little doubt the earliest inhabitants of Sri Lanka.[81]

Vijaya (543–505 BC) reigned for 38 years but had no other children after Kuveni's departure. Nothing much of significance took place during his reign.[82] When he grew old, he became concerned that he would die heirless. So, he decided to bring his twin brother Sumitta from India, to govern his kingdom. He sent a letter to Sumitta, but by the time he could get a reply, he died. The monarchy was succeeded by his chief minister Upatissa (505–504 BC) who became regent and governed the kingdom from Upatissagāma for a year, while awaiting a reply. Meanwhile, in Sinhapura, Sumitta had become the king, and had three sons. His queen was a daughter of the king of Madda (possibly Madra). When Vijaya's messengers arrived, he was himself very old. So, he requested one of his sons to depart for Sri Lanka. His youngest son, Panduvasdeva (504–474 BC), volunteered to go. Panduvasdeva and 32 sons of Sumitta's ministers reached Sri Lanka, where Panduvasdeva became the new ruler.[83][82][84]

Panduvasdeva married an Indian princess, Bhaddakacchana, who was a relative of the Buddha. She came to Sri Lanka with six of her brothers, Ramagona, Rohana, Dighayu, Uruvela, Anuradha and Vigitagama who would go on to found cities all over the country. Anuradhapura, Uruvela, Vijithapura, Dighayu and Rohana are all attributed to them. Anuradha would build the earliest recorded tank in the country's irrigation network[85][86] Panduvasdeva reigned at Vijithapura.[86] It was during this time that the country was subdivided into the three provinces of Pihiti Rata or Raja Rata in the north, Maya Rata in the central-west and Ruhuna Rata in the south-east, identified later with Magama in present-day Hambantota District. The central mountainous region of Sri Lanka was known as Malaya Rata.[85][86]

Abhaya (474–454 BC) succeeded his father Panduvasdeva. The oldest of 10 sons, Abhaya appears to have been a weak and indulgent king. His reign was noted for a rebellion caused by his nephew Pandukabhaya who would go to war with his uncles. Upon losing the battle Abhaya sent a letter to the prince in secret conferring on him the rule of the country south of the river, sharing sovereignty of Sri Lanka. Hearing of this plan angered Abhaya's brothers, Pandukabhaya's uncles, who compelled Abhaya to abdicate and elected Prince Tissa (454–437 BC), the next in line, as regent.[87][88] Tissa was not archknowledged universally as the Sinhalese king, remained as regent while the war continued. The Nineteen Years' War (458–439 BC) ended with the Battle of Labugamaka where with the aid of the Yakkhas and others, Pandukabhaya slew eight of his uncles who were against him.[89][90][91] He took the capital Upatissagāma and preceeded to Anuradhagama where in 438 BC he built it as the new capital of Sri Lanka, renaming it Anuradhapura.[note 3][92]

Anuradhapura period (437 BCE–1017)

[edit]Early Anuradhapura period (437 BC–463 AD)

[edit]

Pandukabhaya (437–367 BC) became the new Sinhalese king and the first to reign from Anuradhapura.[89] Thereafter, Anuradhapura would continue as the Sri Lankan capital city for over 1,400 years.[93] Ancient Sri Lankans excelled at building certain types of structures (constructions) such as tanks, dagobas and palaces.[94] Society underwent a major transformation during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura, with the arrival of Buddhism from India. In 250 BC,[95] Mahinda, the son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka and a bhikkhu (Buddhist monk) arrived in Mihintale carrying the message of Buddhism.[96] His mission won over the monarch, who embraced the faith and propagated it throughout the Sinhalese population.[97]

Succeeding kingdoms of Sri Lanka would maintain a large number of Buddhist schools and monasteries and support the propagation of Buddhism into other countries in Southeast Asia. Sri Lankan Bhikkhus studied in India's famous ancient Buddhist University of Nalanda, which was destroyed by Bakhtiyar Khilji. It is probable that many of the scriptures from Nalanda are preserved in Sri Lanka's many monasteries and that the written form of the Tipitaka, including Sinhalese Buddhist literature, were part of the University of Nalanda.[98] In 245 BC, bhikkhuni Sangamitta arrived with the Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi tree, which is considered to be a sapling from the historical Bodhi tree under which Gautama Buddha became enlightened.[99] It is considered the oldest human-planted tree (with a continuous historical record) in the world. (Bodhivamsa)[100]

Sri Lanka first experienced a foreign invasion during the reign of Suratissa, who was defeated by two horse traders named Sena and Guttika from South India. The next invasion came immediately in 205 BC by a Chola king named Elara, who overthrew Asela and ruled the country for 44 years. Dutugemunu, the eldest son of the southern regional sub-king, Kavan Tissa, defeated Elara in the Battle of Vijithapura. He built Ruwanwelisaya, the second stupa in ancient Sri Lanka, and the Lovamahapaya.[101] There was intense Roman trade with the ancient Tamil country (present day Southern India) and Sri Lanka, establishing trading settlements which remained long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[102][103] During its two and a half millennia of existence, the Kingdom of Sri Lanka was invaded at least eight times by neighbouring South Asian dynasties such as the Chola, Pandya, Chera, and Pallava. These invaders were all subsequently driven back.[104] There also were incursions by the kingdoms of Kalinga (modern Odisha) and from the Malay Peninsula as well. Kala Wewa and the Avukana Buddha statue were built during the reign of Dhatusena.[105]

The Fourth Buddhist council of Theravada Buddhism was held at the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya in Sri Lanka under the patronage of Valagamba of Anuradhapura in 25 BC. The council was held in response to a year in which the harvests in Sri Lanka were particularly poor and many Buddhist monks subsequently died of starvation. Because the Pāli Canon was at that time oral literature maintained in several recensions by dhammabhāṇakas (dharma reciters), the surviving monks recognized the danger of not writing it down so that even if some of the monks whose duty it was to study and remember parts of the Canon for later generations died, the teachings would not be lost.[106] After the Council, palm-leaf manuscripts containing the completed Canon were taken to other countries such as Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.

Sri Lanka was the first Asian country known to have a female ruler: Anula of Anuradhapura (r. 47–42 BC).[107] Ancient Sri Lanka was the first country in the world to establish a dedicated hospital, in Mihintale in the 4th century.[108] It was also the leading exporter of cinnamon in the ancient world. It maintained close ties with European civilisations including the Roman Empire. For example, Bhatikabhaya (22 BC – AD 7) sent an envoy to Rome who brought back red coral, which was used to make an elaborate netlike adornment for the Ruwanwelisaya. In addition, Sri Lankan male dancers witnessed the assassination of Caligula. When Queen Cleopatra sent her son Caesarion into hiding, he was headed to Sri Lanka.[109][110]

The upasampada for bhikkhunis (Buddhist nuns) first arrived in China when Devasāra and ten other bhikkhunis came from Sri Lanka at the request of Chinese women and established the order there in 429.[111]

During the reign of Mahasena (274–301) the Theravada (Maha Vihara) was persecuted and the Mahayanan branch of Buddhism appeared. Later the King returned to the Maha Vihara. Pandu (429) was the first of seven Pandiyan rulers, ending with Pithya in 455. Dhatusena (459–477) "Kalaweva" and his son Kashyapa (477–495) built the famous sigiriya rock palace where some 700 rock graffiti give a glimpse of ancient Sinhala.

Middle Anuradhapura period (463–691)

[edit]

Sri Lankan monarchs undertook some remarkable construction projects such as Sigiriya, the so-called "Fortress in the Sky", built during the reign of Kashyapa I of Anuradhapura, who ruled between 477 and 495. The Sigiriya rock fortress is surrounded by an extensive network of ramparts and moats. Inside this protective enclosure were gardens, ponds, pavilions, palaces and other structures.[112][113]

The 1,600-year-old Sigiriya frescoes are an example of ancient Sri Lankan art at its finest.[112][113] They are one of the best preserved examples of ancient urban planning in the world.[114] They have been declared by UNESCO as one of the seven World Heritage Sites in Sri Lanka.[115] Among other structures, large reservoirs, important for conserving water in a climate with rainy and dry seasons, and elaborate aqueducts, some with a slope as finely calibrated as one inch to the mile, are most notable. Biso Kotuwa, a peculiar construction inside a dam, is a technological marvel based on precise mathematics that allows water to flow outside the dam, keeping pressure on the dam to a minimum.[116]

Late Anuradhapura period (691–1017)

[edit]Mahinda V (981-1017) distracted by a revolt of his own Indian mercenary troops fled to the south-eastern province of Rohana.[117] The Mahavamsa describes the rule of Mahinda V as weak, and the country was suffering from poverty by this time. It further mentions that his army rose against him due to lack of wages. Taking advantage of this internal strife Chola Emperor Rajaraja I invaded Anuradhapura sometime in 993 AD and conquered the northern part of the country and incorporated it into his kingdom as a province named "Mummudi-sola-mandalam" after himself.[10] Rajendra Chola I son of Rajaraja I, launched a large invasion in 1017. The Culavamsa says that the capital at Anuradhapura was "utterly destroyed in every way by the Chola army.[118] There is practically no trace of Chola rule in Anuradhapura, but the conquest had one permanent result in that the capital of Anuradhapura was destroyed, and Polonnaruwa, a military outpost of the Sinhalese,[note 4] was renamed Jananathamangalam and become the new center of administration for the Cholas.[10] Earlier Tamil invaders had only aimed at overlordship of Rajarata in the north, but the Cholas were bent on control of the whole island.

Polonnaruwa period (1017–1232)

[edit]Chola conquest (1017–1070)

[edit]

A partial consolidation of Chola power in Rajarata had succeeded the initial season of plunder. With the intention to transform Chola encampments into more permanent military enclaves, Saivite temples were constructed in Polonnaruva and in the emporium of Mahatittha. Taxation was also instituted, especially on merchants and artisans by the Cholas.[119] In 1014 Rajaraja I died and was succeeded by his son Rajendra Chola I, perhaps the most aggressive king of his line. Chola raids were launched southward from Rajarata into Rohana. By his fifth year, Rajendra claimed to have completely conquered the island. The whole of Anuradhapura including the south-eastern province of Rohana were incorporated into the Chola Empire.[120] As per the Sinhalese chronicle Mahavamsa, the conquest of Anuradhapura was completed in the 36th year of the reign of the Sinhalese monarch Mahinda V, i.e. about 1017–18.[120] But the south of the island, which lacked large an prosperous settlements to tempt long-term Chola occupation, was never really consolidated by the Chola. Thus, under Rajendra, Chola predatory expansion in Sri Lanka began to reach a point of diminishing returns.[119] According to the Culavamsa and Karandai plates, Rajendra Chola led a large army into Anuradhapura and captured Mahinda V's crown, queen, daughter, vast amount of wealth and the king himself whom he took as a prisoner to India, where he eventually died in exile in 1029.[121][120] After the death of Mahinda V the Sinhalese monarchy continued to rule from Rohana until the Sinhalese kingdom was re-established in the north by Vijayabāhu I. Mahinda V was succeeded by his son Kassapa VI (1029–1040).[122][121]

Polonnaruwa period (1055–1232)

[edit]

Following a long war of liberation Vijayabāhu I successfully expelled the Cholas out of Sri Lanka as Chola determination began to gradually falter. Vijayabāhu possessed strategic advantages, even without a unified "national" force behind him. A prolonged war of attrition was of greater benefit to the Sinhalese than to the Cholas. After the accession of Virarajendra Chola (1063–1069) to the Chola throne, the Cholas were increasingly on the defensive, not only in Sri Lanka, but also in peninsular India, where they were hard-pressed by the attacks of the Chalukyas from the Deccan.[123] Vijayabāhu launched a successful two-pronged attack upon Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva, when he could finally establish a firm base in southern Sri Lanka. Anuradhapura quickly fell and Polonnaruva was captured after a prolonged siege of the isolated Chola forces.[121][124] Virarajendra Chola was forced to dispatch an expedition from the mainland to recapture the settlements in the north and carry the attack back into Rohana, in order to stave off total defeat. What had begun as a profitable incursion and occupation was now deteriorating into desperate attempts to retain a foothold in the north. After a further series of indecisive clashes the occupation finally ended in the withdrawal of the Cholas. By 1070 when Sinhalese sovereignty was restored under Vijayabāhu I, he had reunited the country for the first time in over a century.[125][126][124]

Vijayabāhu I (1055–1110), descended from, or at least claimed to be descended from the House of Lambakanna II. He crowned himself in 1055 at Anuradhapura but continued to have his capital at Polonnaruwa for it being more central and made the task of controlling the turbulent province of Rohana much easier.[10] Aside from leading the prolonged resistance to Chola rule Vijayabāhu I proved to be outstanding in administration and economic regeneration after the war and embarked on the rehabilitation of the island's irrigation network and the resuscitation of Buddhism in the country.[124] Buddhism had suffered severely in the country during the Chola rule, where precedence was given to Saivite Hinduism.[127] The influnece of Hinduism on religion and society during this period also saw a hardening of caste attitudes in the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa.[128] Economic, Social structure, art and architecture of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was a continuation and development of that of the Anuradhapura period. Internal and external trade made the kingdom more prosperous than just relying on its primarily agricultural economy.[129] Seafaring crafts were built in Sri Lanka and were known to have sailed as far as China, some may have even been used as troop transport ships to Burma. Howevere those used in External trade were mostly of foreign construction.[130] The island's importance as an important center of international trade attracted many foreign merchants, the most prominant of which were descendants of Arab traders. The south of India also hosted settlements of these Arab merchants, and they would become a dominant influence on the country's external trade, but by no means was a monopoly.[130]

Upon Vijayabāhu I's death a succession dispute jeopardized the recovery from the Chola conquest. His successors proved unable to consolidate power plunging the kingdom into a period of civil war, from which Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186), a closely related royal emerged.[132] Parākramabāhu I established control over the island and secured his recognition as Vijayabāhu's heir by obtaining the Tooth and bowl relics of the Buddha, which by now had become essential to the legitimacy of royal authority in Sri Lanka.[132]

By the time of the Polonnaruwa period the Sinhalese has centuries of experience in irrigation technology behind them and so the Polonnaruwa kings, especially Parākramabāhu the Great, made distinguished contributions of their own at honing these techniques to cope with the special requirements of the immense irrigation projects at the time.[133] Sri Lanka's irrigation network was extensively expanded during the reign of Parākramabāhu the Great.[134] He built 1470 reservoirs – the highest number by any ruler in Sri Lanka's history – repaired 165 dams, 3910 canals, 163 major reservoirs, and 2376 mini-reservoirs.[134] His most famous construction is the Parakrama Samudra, the largest irrigation project of medieval Sri Lanka. Having re-established the political unification of the island, Parākramabāhu continued Vijayabāhu policy in keeping a tight check on separatist tendencies within the island, especially in Rohana where particularism was a deeply ingrained political tradition. Parākramabāhu faced a formidable rebellion in 1160 as Rohana did not accept its loss of autonomy lightly. A rebellion in 1168 in Rajarata also manifested. Both were put down with great severity and all vestiges of its former autonomy purposefully eliminated. Particularism was now much less tolerated than it was during the Anuradhapura period. This new over-centralization of authority in Polonnaruwa would however work against the Sinhalese in the future and the country would eventually pay dearly as a result.[135]

Parākramabāhu's reign is memorable for two major campaigns – in the south of India as part of a Pandyan war of succession, and a punitive strike against the kings of Ramanna (Myanmar) for various perceived insults to Sri Lanka.[136][137] Parākramabāhu I was the last of the great ancient Sri Lankan kings.[135] His reign is considered as a time when Sri Lanka was at the height of its power.[138][137] Parākramabāhu had no sons, which complicated the the problem of succession upon his death. Amid the succession crisis a scion of a foreign dynasty, Niśśaṅka Malla established his claims as a Prince of Kalinga,[note 6] claiming to be chosen and trained for the succession by Parākramabāhu himself.[135] He was also either the son-in-law or nephew of Parākramabāhu.[139]

Niśśaṅka Malla (1187–1196) was the first monarch of the House of Kalinga and the only Polonnaruwa monarch to rule over the whole island after Parākramabāhu. His reign gave the country a brief decade of order and stability before the speedy and catastrophic break-up of the hydraulic civilisations of the dry zone.[135] With his death there was a renewal of political dissension, now complicated by dynastic disputes.[140] Though he and his predecessors Vijayabāhu and Parākramabāhu achieved much in state building. The conspicuous lack of restraint, especially that of Parākramabāhu, in combination with an ambitious and venturesome foreign policy, and an expensive diversion of state resources towards public works projects, sapped the strength of the country and contributed to its sudden and complete collapse.[135]

The House of Kalinga would maintain itself in power, but only with the support of an influential faction within the country. Their survival owed much to the inability of the factions opposing them to come up with an aspirant to the throne with a politically viable claim, or sufficient durability once installed in power, therefore the House of Kalinga's hold on the throne was inherently precarious. On three occasions, the queen of Parākramabāhu, Lilāvatī, was raised to the throne out of desperation.[140] The factional struggle and political instability attracted the attention of South Indian adventures bent on plunder, culminating in the devastating campaign of pillage under Māgha of Kalinga (1215–1236), claiming the inheritance of the kingdom through his kinsman who reigned before.[141][140]

Māgha, a bigoted Hindu, persecuted Buddhists, despoiling the temples and giving away lands of the Sinhalese to his followers.[141] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of the Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power.[142] Māgha's rule of 21 years and its aftermath are a watershed in the history of the island, creating a new political order.[140] After his death in 1255 Polonnaruwa ceased to be the capital, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power and from then on there were two, or sometimes three rulers existing concurrently.[140][143] Parakramabahu VI of Kotte (1411-1466) would be the only other Sinhalese monarch to establish control over the whole island after this period.[140] The Rajarata, the traditional location of the Sinhalese kingdom and Rohana, the previously autonomous subregion were abandoned. Two new centers of political authority emerged as a result of the fall of the Polonnaruwa kingdom.

In the face of repeated South Indian invasions the Sinhalese monarchy and people retreated into the hills of the wet zone, further and further south, seeking primarily security. The capital was abandoned and moved to Dambadeniya by Vijayabāhu III establishing the Dambadeniya era of the Sinhalese kingdom.[144][145] A second poilitical center emerged in the north of the island where Tamil settlers from previous Indian incursions occupied the Jaffna Peninsula and the Vanni.[note 7] Many Tamil members of invading armies, mercenaries, joined them rather than returning to India with their compatriots. By the 13th century the Tamils too withdrew from the Vanni almost entirely into the Jaffna peninsula where an independant Tamil kingdom had been established.[143][142]

Transitional period (1232–1597)

[edit]Early Transitional period (1232–1521)

[edit]Capital at Dambadeniya

[edit]The next three centuries were marked by kaleidoscopic shifting of the national capital from the north central to the south and central of the island.[141] The Jaffna kingdom came under the rule of the south on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest by Parâkramabâhu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal. He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467.[146]

Capital at Gampola

[edit]The capital was moved to Gampola by Buwanekabahu IV, he is said to be the son of Sawulu Vijayabāhu. During this time, a muslim traveller and geographer named Ibn Battuta came to Sri Lanka and wrote a book about it. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya is the main building made in the Gampola Kingdom period. The Lankatilaka Viharaya is also a main building built in Gampola.

Chinese admiral Zheng He and his naval expeditionary force landed at Galle, Sri Lanka in 1409 and got into battle with the local king Vira Alakesvara of Gampola. Zheng He captured King Vira Alakesvara and later released him.[147][148][149][150] Zheng He erected the Galle Trilingual Inscription, a stone tablet at Galle written in three languages (Chinese, Tamil, and Persian), to commemorate his visit.[151][152]

Capital at Kotte

[edit]By the Sixteenth century the population of the island was approximately 750,000, the majority, 400-450 thousand lived in the Kingdom of Kotte which was the largest and most powerful polity on the island.[153][154] Its boundaries reached from the Malvatu Oya in the North to the Valave River in the South, and from the central highlands to the western coast. The Kotte kings regarded themselves as Chakravartis (Emperors), laying claim to the whole island, after Parakramabahu VI, but actual power was limited to within their own boundaries.[155] Dispite areas under its direct jurisdiction changing from time to time, Kotte held the island's lands where trade and agriculture were most developed. The Kotte kings were the largest land owners in the country, whith much of the royal income coming from land revenue as opposed to trade. The Gabadāgam (Royal lands) accounted for more than three quarter of the annual royal income, and monetization of the economy in the littoral region began at least as far back as the fifteenth century.[154]

During this time the Portuguese entered into the internal politics of Sri Lanka. Largely by accident, first contact between the two nations was in 1505-06. But it was not until 1517-18 that the Portuguese sought to establish a fortified trading settlement in order to establish control over the island's Cinnamon trade, as opposed to territorial conquest.[156] The building of a fort, near Colombo, had to be given up due popular hostility that was fanned by Moorish traders, who had established themselves on the island and controled a large portion of its external trade.[156] The Portuguese at no stage established dominance over the politics of South Asia, but sought to do so over its commerce by means of subjugation through naval power. Using their superior technology and sea power at points of weakness or divisions, the Portuguese would attain influence in greater proportions to their actual strength. Portuguese anxiety to establish a Bridgehead in Sri Lanka to control the island's Cinnamon trade drew them further into the politics of Sri Lanka.[157]

Kotte suffered from persistant succession disputes during this time. Though all were subordinate to the emperor of Kotte, brothers of the king would take the title Raja (king) and rule parts of the kingdom. This practice was possibly tollerated to humour princes who had some claim to the throne by giving them positions of responsibility, and the belief that having loyal relatives in outlying disticts afforded some security to the king. However this political structure inevitably led to its own weakening in the long run, as those princes, who could, virtually administered the areas they claimed as autonomous principalities.[158]

Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1521–1597)

[edit]

In 1521 the Vijayabā Kollaya was one such and the most eventful of succession disputes in the kingdom and would trigger the most chaotic period in the history of Sri Lanka. Vijayabāhu VI, who had four sons by two wives, sought to select his youngest son for the succession of the kingdom. In reaction the three older brothers assassinated their father, with the assistance of the Kandyan ruler, and divided the kingdom among themselves. With this partition the fragmentation of the Sri Lankan polity seemed well beyond the capacity of any statesman to repair.[158] The Kandyan ruler took advantage of the situation in a cynical and shrewd move to aggrevate the political instability as an opportunity to assert their independance from the control of Kotte. Kanday ruler Jayavira Bandara (1511–52) readily aided the three princes against their father, and it was clear the decline of the Kingdom of Kotte was necessary for the rise of the Kingdom of Kandy.[156]

Kandyan period (1597–1815)

[edit]

When the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen landed in 1602, the king of Kandy appealed to him for help.

In 1619, succumbing to attacks by the Portuguese, the independent existence of Jaffna kingdom came to an end.[159]

During the reign of the Rajasinghe II, Dutch explorers arrived on the island. In 1638, the king signed a treaty with the Dutch East India Company to get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas.[160] The main conditions of the treaty were that the Dutch were to hand over the coastal areas they had captured to the Kandyan king in return for a Dutch monopoly over the cinnamon trade on the island. The following Dutch–Portuguese War resulted in a Dutch victory, with Colombo falling into Dutch hands by 1656. The Dutch remained in the areas they had captured, thereby violating the treaty they had signed in 1638. By 1660 they controlled the whole island except the land-locked kingdom of Kandy. The Dutch (Protestants) persecuted the Catholics and the remaining Portuguese settlers but left Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims alone. The Dutch levied far heavier taxes on the people than the Portuguese had done.[citation needed] An ethnic group named Burgher people emerged in Sri Lankan society as a result of Dutch rule.[161]

The Kingdom of Kandy was the last independent monarchy of Sri Lanka.[162] In 1595, Vimaladharmasurya brought the sacred Tooth Relic, the traditional symbol of royal and religious authority amongst the Sinhalese, to Kandy, and built the Temple of the Tooth.[162] In spite of on-going intermittent warfare with Europeans, the kingdom survived. Later, a crisis of succession emerged in Kandy upon king Vira Narendrasinha's death in 1739. He was married to a Telugu-speaking Nayakkar princess from South India (Madurai) and was childless by her.[162]

Eventually, with the support of bhikku Weliwita Sarankara, the crown passed to the brother of one of Narendrasinha's princesses, overlooking the right of "Unambuwe Bandara", Narendrasinha's own son by a Sinhalese concubine.[163] The new king was crowned Sri Vijaya Rajasinha later that year. Kings of the Nayakkar dynasty launched several attacks on Dutch controlled areas, which proved to be unsuccessful.[164]

Vannimai were feudal land divisions ruled by Vanniar chiefs south of the Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka. Pandara Vanniyan allied with the Kandy Nayakars led a rebellion against the British and Dutch colonial powers in Sri Lanka in 1802. He was able to liberate Mullaitivu and other parts of northern Vanni from Dutch rule. In 1803, Pandara Vanniyan was defeated by the British and Vanni came under British rule.[165] During the Napoleonic Wars, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, Great Britain occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1795-96.[166] Two years later, in 1798, the Kandyan king, Sri Rajadhi Rajasinha died of a fever. Following his death, a nephew of Rajadhi Rajasinha, eighteen-year-old Kannasamy, was crowned.[167] The young king, now named Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, faced a British invasion in 1803 but successfully retaliated. The First Kandyan War ended in a stalemate.[167]

British Ceylon period (1815–1948)

[edit]

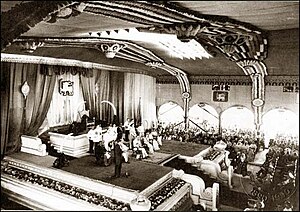

As a result of the Treaty of Amiens the entire coastal area was under the British East India Company. On 14 February 1815, Kandy was occupied by the British in the Second Kandyan War.[167] Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the last native monarch of Sri Lanka, was exiled to India.[168] The Kandyan Convention formally ceded the entire country to the British Empire, ending Sri Lanka's independence. Attempts by Sri Lankan noblemen to undermine British power in 1818 during the Great Rebellion of 1817–18 were thwarted by Governor Robert Brownrigg.[108]

The Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1833 ushered in a period of reformist zeal that would never again be matched during British rule.[169] They introduced a utilitarian and liberal political culture to the country based on the rule of law and amalgamated the Kandyan and maritime provinces as a single unit of government. An executive council and a legislative council were established, later becoming the foundation of a representative legislature. By this time, experiments with coffee plantations were largely successful.[170]

Soon coffee became the primary commodity export of Sri Lanka. However falling coffee prices as a result of the depression of 1847 stalled economic development and prompted the governor to introduce a series of taxes on firearms, dogs, shops, boats, etc., and to reintroduce a form of rajakariya, requiring six days free labour on roads or payment of a cash equivalent.[170] These harsh measures antagonised the locals, and another rebellion broke out in 1848.[171] A devastating leaf disease, Hemileia vastatrix, struck the coffee plantations in 1869, destroying the entire industry within fifteen years.[172] The British quickly found a replacement: abandoning coffee, they began cultivating tea instead. Tea production in Sri Lanka thrived in the following decades. Large-scale rubber plantations began in the early 20th century.

By the end of the 19th century, a new educated social class transcending race and caste arose through British attempts to staff the Ceylon Civil Service and the legal, educational, and medical professions.[173] New leaders represented the various ethnic groups of the population in the Ceylon Legislative Council on a communal basis. Buddhist and Hindu revivalism reacted against Christian missionary activities.[174] The first two decades in the 20th century are noted by the unique harmony among the Sinhalese and Tamil political leadership, which dissipated by the 1920s.[175]

In 1919, major Sinhalese and Tamil political organisations united to form the Ceylon National Congress (CNC), under the leadership of Ponnambalam Arunachalam,[177] pressing colonial masters for more constitutional reforms. But without massive popular support, and with the governor's encouragement for "communal representation" by creating a "Colombo seat" that dangled between Sinhalese and Tamils, the Congress lost momentum towards the mid-1920s.[178]

The Donoughmore reforms of 1931 repudiated the communal representation and introduced universal adult franchise[note 8]. This step was strongly criticised by the Tamil political leadership, who realised that they would be reduced to a minority in the newly created State Council of Ceylon, which succeeded the legislative council.[179][180] In 1937, Tamil leader G. G. Ponnambalam demanded a 50–50 representation (50% for the Sinhalese and 50% for other ethnic groups) in the State Council. However, this demand was not met by the Soulbury reforms of 1944–45.

Sri Lanka was a front-line British base against the Japanese during World War II. Sri Lankan opposition to the war led by the Marxist organizations and the leaders of the LSSP pro-independence group were arrested by the Colonial authorities. On 5 April 1942, the Indian Ocean raid saw the Japanese Navy bomb Colombo.

The Sinhalese leader D. S. Senanayake left the CNC on the issue of independence, disagreeing with the revised aim of 'the achieving of full independance' in favour of Dominion status, although his real reasons were more subtle.[181] He subsequently formed the United National Party (UNP) in 1946,[182] when a new constitution was agreed on, based on the behind-the-curtain lobbying of the Soulbury commission. At the elections of 1947, the UNP won a minority of seats in parliament, but cobbled together a coalition with the Sinhala Maha Sabha party of Solomon Bandaranaike and the Tamil Congress of G.G. Ponnambalam. The successful inclusions of the Tamil-communalist leader Ponnambalam, and his Sinhalese counterpart Bandaranaike were a remarkable political balancing act by Senanayake.

Sri Lanka (1948–present)

[edit]

The Soulbury constitution ushered in Dominion status, with independence proclaimed on 4 February 1948.[183] D. S. Senanayake became the first Prime Minister of Ceylon.[183] Prominent Tamil leaders including Ponnambalam and Arunachalam Mahadeva joined his cabinet.[184] The British Navy remained stationed at Trincomalee until 1956. A countrywide popular demonstration against withdrawal of the rice ration, known as 1953 Hartal, resulted in the resignation of prime minister Dudley Senanayake.[185]

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was elected prime minister in 1956. His three-year rule had a profound impact through his self-proclaimed role of "defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture".[186] He introduced the controversial Sinhala Only Act, recognising Sinhala as the only official language of the government. Although partially reversed in 1958, the bill posed a grave concern for the Tamil community, which perceived in it a threat to their language and culture.[187][188][189]

The Federal Party (FP) launched a movement of non-violent resistance (satyagraha) against the bill, which prompted Bandaranaike to reach an agreement (Bandaranaike–Chelvanayakam Pact) with S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, leader of the FP, to resolve the looming ethnic conflict.[190] The pact proved ineffective in the face of ongoing protests by opposition and the Buddhist clergy. The bill, together with various government colonisation schemes, contributed much towards the political rancour between Sinhalese and Tamil political leaders. Bandaranaike was assassinated by an extremist Buddhist monk in 1959.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the widow of S. W. R. D., took office as prime minister in 1960, and withstood an attempted coup d'état in 1962. During her second term as prime minister, the government instituted socialist economic policies, strengthening ties with the previously unrecognized Soviet Union and China, while promoting a policy of non-alignment. In 1971, Ceylon experienced a Marxist youth insurrection, led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, the biggest revolt by the youth in recorded history.[191] Though the insurgency failed, it left an indelible mark on the country.[192] The rebels would go on to play a part in shaping the future while the after the insurrection the Bandaranaike government tended to become increasingly authoritarian.[193] In 1972, the country became a republic and was renamed Sri Lanka, repudiating its dominion status. Prolonged minority grievances and the use of communal emotionalism as an election campaign weapon by both Sinhalese and Tamil leaders abetted a fledgling Tamil militancy in the north during the 1970s.[194] The policy of standardisation by the Bandaranaike government to rectify disparities created in university enrolment, which was in essence an affirmative action to assist geographically disadvantaged students to obtain tertiary education,[195] resulted in reducing the proportion of Tamil students at university level and acted as the immediate catalyst for the rise of militancy.[196] The assassination of Jaffna Mayor Alfred Duraiappah in 1975 by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) marked a crisis point.[197][198]

The government of J. R. Jayewardene swept to power in 1977, defeating the largely unpopular United Front government. Jayawardene introduced a new constitution, together with a free-market economy and a powerful executive presidency modelled on functional aspects of previous constitutions and features of the American, British and French systems of government.[199] It made Sri Lanka the first South Asian country to liberalise its economy. Beginning in 1983, ethnic tensions were manifested in an on-and-off insurgency against the government by the LTTE. An LTTE attack on 13 soldiers resulted in the anti-Tamil riots in July 1983, allegedly backed by Sinhalese hard-line ministers, which resulted in more than 150,000 Tamil civilians fleeing the island, seeking asylum in other countries.[200]

Lapses in foreign policy resulted in India strengthening the Tigers by providing arms and training.[201][202][203] In 1987, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord was signed and the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was deployed in northern Sri Lanka to stabilise the region by neutralising the LTTE.[204] The same year, the JVP launched a second insurrection in Southern Sri Lanka,[205] necessitating redeployment of the IPKF in 1990.[206] In October 1990, the LTTE expelled Sri Lankan Moors (Muslims by religion) from northern Sri Lanka.[207] In 2002, the Sri Lankan government and LTTE signed a Norwegian-mediated ceasefire agreement.

The 2004 Asian tsunami killed over 35,000 in Sri Lanka.[208] From 1985 to 2006, the Sri Lankan government and Tamil insurgents held four rounds of peace talks without success. Both LTTE and the government resumed fighting in 2006, and the government officially backed out of the ceasefire in 2008. In 2009, under the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the LTTE and re-established control of the entire country by the Sri Lankan Government.[209] Overall, between 60,000 and 100,000 people were killed during the 26 years of conflict.[210][211]

Forty thousand Tamil civilians may have been killed in the final phases of the Sri Lankan civil war, according to an Expert Panel convened by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. The exact number of Tamils killed is still a speculation that needs further study.[212] Following the LTTE's defeat, the Tamil National Alliance, the largest Tamil political party in Sri Lanka, dropped its demand for a separate state in favour of a federal solution.[213][214] The final stages of the war left some 294,000 people displaced.[215][216] The UN Human Rights Council has documented over 12,000 named individuals who have undergone disappearance after detention by security forces in Sri Lanka, the second highest figure in the world since the Working Group came into being in 1980.[217]

According to the Ministry of Resettlement, most of the displaced persons had been released or returned to their places of origin, leaving only 6,651 in the camps as of December 2011.[218] In May 2010, President Rajapaksa appointed the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) to assess the conflict between the time of the ceasefire agreement in 2002 and the defeat of the LTTE in 2009.[219][220] Sri Lanka has emerged from its 26-year war to become one of the fastest growing economies of the world.[221][222]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Madhura is identified with Madurai, a city in South India; Pandu is identified with the Pandyas

- ^ Not to be confused with the Pulindas of India

- ^ After one of Vijaya's ministers and Pandukabhaya's own great-uncle who both resided there and where both named Anuradha.

- ^ As noted by its native name of Kandavura Nuvara (the camp city)

- ^ Considered as one of the oldest Hindu shrine in Polonnaruwa founded during Chola occupation built during 1015-1044[131]

- ^ The birthplace of Prince Vijaya and the ancestors of the Sinhalese.

- ^ The land between Anuradhapura and Jaffna

- ^ The franchise stood at 4% before the reforms

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Deraniyagala 1996.

- ^ Geiger 1930, p. 228.

- ^ Gunasekara 1900.

- ^ a b c Coming of Vijaya 2019.

- ^ a b Geiger 1930, p. 208.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Pieris 2007.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Sastri 1935, p. 172–173.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1994, p. 7–9.

- ^ Kulke, Kesavapany & Sakhuja 2009, p. 195–.

- ^ Gunawardena 2005, p. 71–.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 409.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 161.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Stein 1994.

- ^ a b c Blaze 1933, p. 2.

- ^ latlong2019.

- ^ BBC 2007.

- ^ Garg 1992, p. 142.

- ^ Rediff.com 2014.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Adam's Bridge 2015.

- ^ Aves 2003, p. 372.

- ^ Lonely Planet 2014.

- ^ a b United Nations Environment Programme 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization 2014.

- ^ International Union for Conservation of Nature 2014.

- ^ indexmundi.com 2009.

- ^ Vitharana 2008.

- ^ Cairn Lanka 2009, p. iv–vii.

- ^ Mittermeier, Myers & Mittermeier 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Environment Sri Lanka 2014.

- ^ news.mongabay.com 2012.

- ^ Ecotourism Sri Lanka 2014.

- ^ earthtrends.wri.org 2007, p. 4.

- ^ UNESCO 2006.

- ^ srilankanwaterfalls.net 2009.

- ^ MSN Encarta Encyclopedia 2009.

- ^ angelfire.com 2014.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1986, p. 165–265.

- ^ De Silva 1981, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 454.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 4.

- ^ Keshavadas 1988.

- ^ Parker 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Edirisinghe 2009.

- ^ Deraniyagala 2014.

- ^ ParPossehlker 1990.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 734.

- ^ Deraniyagala 1992, p. 709-29.

- ^ Karunaratne & Adikari 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Mogren 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Coningham 1999.

- ^ Lankalibrary.com 2012.

- ^ Deraniyagala 2007.

- ^ Dailynews.lk 2008.

- ^ Holt 2011, p. 53-56.

- ^ Ranwella 2000.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 6.

- ^ Ariyadasa 2015.

- ^ The Mahavamsa 2019.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 5.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 7.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e The Consecrating of Vijaya 2019.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 8.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 8.

- ^ Wanasundera 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 9.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 10.

- ^ Spencer 2002, p. 74–77.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 10-11.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 11.

- ^ The Consecrating of Panduvasudeva 2019.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Codrington 1926, p. 9.

- ^ Blaze 1933, p. 18.

- ^ a b Blaze 1933, p. 14.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 10.

- ^ worldheritagesite.org 2004.

- ^ mysrilankaholidays.com 2014.

- ^ Perera 2014.

- ^ Holt 2004, p. 795–799.

- ^ The Mahavamsa 2014.

- ^ buddhanet.net 2014.

- ^ Maung Paw, p. 6.

- ^ Gunawardana 2012.

- ^ beyondthenet.net 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Starr 1956, p. 27–30.

- ^ Curtin 1984, p. 100.

- ^ De Silva 2014.

- ^ Sarachchandra 1977, p. 121–122.

- ^ Lopez 2013, p. 200.

- ^ sltda.gov.lk 2014.

- ^ a b lankalibrary.com 2014.

- ^ Weerakkody 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Flickr 2008.

- ^ Maung Paw, p. 7.

- ^ a b Ponnamperuma 2013.

- ^ a b Bandaranayake 1999.

- ^ Bandaranayake 1974, p. 321.

- ^ AsiaExplorers.com 2014.

- ^ slageconr.net 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Siriweera 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 411.

- ^ a b Spencer 1976, p. 416.

- ^ a b c Sastri 1935, p. 199–200.

- ^ a b c Spencer 1976, p. 417.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 741.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 81-2.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 57.

- ^ Lambert 2014.

- ^ Bokay 1966, p. 93–95.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 96.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 92.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 99.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 105.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 83.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 93.

- ^ a b Herath 2002, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e De Silva 2005, p. 84.

- ^ International Lake Environment Committee 2011.

- ^ a b ParakramaBahu I: 1153 - 1186 Eighth massa 2019.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 64.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f De Silva 2005, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Codrington 1926, p. 67.

- ^ a b Indrapala 1969, p. 16.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 76.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Holt 1991, p. 304.

- ^ South East Aisa in Ming Shi-lu 2005.

- ^ Voyages of Zheng He 1405–1433 2015.

- ^ Ming Voyages 2015.

- ^ Admiral Zheng He 2014.

- ^ The trilingual inscription of Admiral Zheng 2015.

- ^ Zheng He 2015.

- ^ Pieris 2011.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 142.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 143.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 145.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 147.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 144.

- ^ Knox 1681, p. 19–47.

- ^ Anthonisz 2003, p. 37–43.

- ^ Bosma 2008.

- ^ a b c The Sunday Times 2014.

- ^ Dharmadasa 1992, p. 8–12.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 140.

- ^ Tambiah 1954, p. 65.

- ^ colonialvoyage.com 2014.

- ^ a b c scenicsrilanka.com 2014.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 173.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 338.

- ^ a b Nubin 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Wimalaratne 2014.

- ^ Mills 1964, p. 246.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 116–117.

- ^ Bond 1992, p. 11–22.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 387.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 480.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 386.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 389–395.

- ^ Hellmann-Rajanayagam 2014.

- ^ De Silva 1981, p. 423.

- ^ Atimes.com 2012.

- ^ Countrystudies.us, p. 246.

- ^ a b Sinhalese Parties 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 121–122.

- ^ Weerakoon 2014.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 123.

- ^ Ganguly 2003, p. 136–138.

- ^ Schmid & Schroeder 2001, p. 185.

- ^ BBC News 2013.

- ^ Peebles 2006, p. 109–111.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 663.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 664.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 665.

- ^ Nubin 2002, p. 128–129.

- ^ De Silva 1997, p. 248–254.

- ^ Jayasuriya 1981.

- ^ Hoffman 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Gunaratna 1998.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 684.

- ^ Jayatunge 2010.

- ^ Sunday Times 1997.

- ^ Express India 1997.

- ^ Wijesinghe 2014.

- ^ Stokke & Ryntveit 2000, p. 285–304.

- ^ Gunaratna 1998, p. 353.

- ^ Asia Times-Chapter 30 2002.

- ^ lankanewspapers.com 2008.

- ^ WSWS.org 2005.

- ^ Weaver & Chamberlain 2009.

- ^ ABC 2009.

- ^ Olsen 2014.

- ^ Hindustan Times 2011.

- ^ Haviland 2010.

- ^ Burke 2010.

- ^ The Sunday Observer 2011.

- ^ Amnesty International 2009.

- ^ BBC 2009.

- ^ Ministry of Resettlement in Sri Lanka 2011, p. 2.

- ^ ReliefWeb 2010.

- ^ Mallawarachi 2011.

- ^ Business Insider 2014.

- ^ adaderana.lk 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Oldenberg, Hermann, ed. (1879). The Dîpavaṃsa: An Ancient Buddhist Historical Record. London & Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate.

- Mahānāma; tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; tr. Bode, Mabel Haynes (1912). The Mahāvaṃsa, Or, The Great Chronicle of Ceylon. London: Oxford University Press.

- Dhammakitti; Ger tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; Eng tr. Rickmers, Christian Mabel (1929). Cūḷavaṃsa: Being the More Recent Part of the Mahāvaṃsa, Part 1. London: Oxford University Press.

- Gunasekara, B., ed. (1900). The Rajavaliya: Or a Historical Narrative of Sinhalese Kings. Colombo: George J. A. Skeen, Government Printer, Ceylon.

- Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Richard Chiswell.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Histories

- Parker, Henry (1909). Ancient Ceylon. London: Luzac & Co.

- Codrington, H. W. (1926). A Short History Of Ceylon. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Senaveratna, John M. (1930). The Story of the Sinhalese from the Most Ancient Times Up to the End of "the Mahavansa" Or Great Dynasty: Vijaya to Maha Sena, B.C. 543 to A.D.302. Colombo: W. M. A. Wahid & Bros. ISBN 9788120612716.

- Blaze, L. E. (1933). History of Ceylon (PDF) (Eighth ed.). Colombo: Christian literature society for India and Africa.

- Nicholas, Cyril Wace; Paranavitana, Senerat (1961). A Concise History of Ceylon: From the Earliest Times to the Arrival of the Portuguese in 1505. Ceylon University Press.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (December 1992). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective (1st ed.). Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 9789559159001.

- de Silva, K. M. (1981). A History of Sri Lanka. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520043206.

- Siriweera, W. I. (2002). History of Sri Lanka: From Earliest Times Up to the Sixteenth Century. Dayawansa Jayakody & Company. ISBN 9789555512572.

- de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. ISBN 9789558095928.

- Peebles, Patrick (2006). The History of Sri Lanka. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313332050.

- Other Books

- All Ceylon Buddhist Congress (1956). The Betrayal of Buddhism: An Abridged Version of the Report of the Buddhist Committee of Inquiry. Dharmavijaya Press.

- European Association of Social Anthropologists (2001). Schmidt, Bettina E.; Schroeder, Ingo W. (eds.). Anthropology of Violence and Conflict. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415229050.

- Institute for International Studies (Peradeniya, Sri Lanka) (1992). Jayasekera, P. V. J. (ed.). Security dilemma of a small state. South Asian Publishers. ISBN 9788170031482.

- Anthonisz, Richard Gerald (2003). The Dutch in Ceylon: An Account of Their Early Visits to the Island, Their Conquests, and Their Rule Over the Maritime Regions During a Century and a Half. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120618459.

- Arseculeratne, S. N. (1991). Sinhalese Immigrants in Malaysia & Singapore, 1860-1990: History Through Recollections. Colombo: K.V.G. De Silva & Sons. ISBN 9789559112013.

- Aves, Edward (2003). Sri Lanka. Footprint. ISBN 9781903471784.

- Bandaranayake, S. D. (1974). Sinhalese Monastic Architecture: The Viháras of Anurádhapura. BRILL. ISBN 9789004039926.

- Bandaranayake, Senaka; Madhyama Saṃskr̥tika Aramudala (1999). Sigiriya: city, palace, and royal gardens. Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs. ISBN 9789556131116.

- Bond, George Doherty (1992). The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120810471.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971693732.

- Brohier, Richard Leslie (1933). The Golden Age Of Military Adventure In Ceylon 1817-1818. Colombo: Plâté limited.

- Brown, Michael Edward; Ganguly, Sumit (2003). Fighting Words: Language Policy and Ethnic Relations in Asia. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262523332.

- Chattopadhyaya, Haraprasad (1994). Ethnic Unrest in Modern Sri Lanka: An Account of Tamil-Sinhalese Race Relations. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788185880525.

- Crusz, Noel (2001). The Cocos Islands Mutiny. Freemantle Arts Centre Press. ISBN 9781863683104.

- De Silva, R. Rajpal Kumar (1988). Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon 1602-1796: A Comprehensive Work of Pictorial Reference With Selected Eye-Witness Accounts. Brill Archive. ISBN 9789004089792.

- Dharmadasa, K. N. O. (1992). Language, Religion, and Ethnic Assertiveness: The Growth of Sinhalese Nationalism in Sri Lanka. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472102884.

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170223757.

- Gunaratna, Rohan (1998). Sri Lanka's Ethnic Crisis & National Security. South Asia Network on Conflict Research. ISBN 9789558093009.

- Gunawardena, Charles A. (2005). Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9781932705485.

- Herath, R. B. (2002). Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis: Towards a Resolution. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781553697930.

- Hoffman, Bruce (2006). Inside Terrorism. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231126991.

- Holt, John (1991). Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteśvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195064186.

- Holt, John (2011). The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822349822.

- Irons, Edward A. (2008). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Facts on File. ISBN 9780816054596.

- Jayasuriya, J. E. (1981). Education in the Third World: Some Reflections. Somaiya.

- Keshavadas, Sadguru Sant (1988). Ramayana at a Glance. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120805453.

- Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812309372.

- Liyanagamage, Amaradasa (1968). The Decline of Polonnaruwa and the Rise of Dambadeniya (circa 1180 - 1270 A.D.). Department of Cultural Affairs.

- Mendis, Ranjan Chinthaka (1999). The Story of Anuradhapura: Capital City of Sri Lanka from 377 BC - 1017 Ad. Lakshmi Mendis. ISBN 9789559670407.

- Mills, Lennox A. (1964). Ceylon Under British Rule, 1795-1932. Cass. ISBN 9780714620190.

- Mittal, J. P. (2006). History Of Ancient India (a New Version)From 4250 BC To 637 AD. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788126906161.

- Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina Goettsch; Myers, Norman (1999). Hotspots: Earth's Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CEMEX. ISBN 9789686397581.

- Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. ISBN 9781590335734.

- Perera, Lakshman S. (2001). The Institutions of Ancient Ceylon from Inscriptions: From 831 to 1016 A.D., pt. 1. Political institutions. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. ISBN 9789555800730.

- Pieris, Paulus Edward (1918). Ceylon and the Hollanders, 1658-1796. Tellippalai: American Ceylon Mission Press.

- Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty, Limited. ISBN 9780987345110.

- Rambukwelle, P. B. (1993). Commentary on Sinhala kingship: Vijaya to Kalinga Magha. P.B. Rambukwelle. ISBN 9789559556503.

- Sarachchandra, B. S. (1977). අපේ සංස්කෘතික උරුමය [Our Cultural Heritage] (in Sinhala). V. P. Silva.

- Siriweera, W. I. (1994). A study of the economic history of pre-modern Sri Lanka. Vikas Pub. House. ISBN 9780706976212.

- Spencer, Jonathan (2002). Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203407417.

- Tambiah, Henry Wijayakone (1954). The laws and customs of the Tamils of Ceylon. Tamil Cultural Society of Ceylon.

- Tinker, Hugh (1990). South Asia: A Short History. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824812874.

- Wanasundera, Nanda Pethiyagoda (2002). Sri Lanka. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761414773.

- Sastri, K. A (1935). The CōĻas. Madras: University of Madras.

- Journals

- Bokay, Mon (1966). "Relations between Ceylon and Burma in the 11th Century A.D". Artibus Asiae. Supplementum. 23. JSTOR: 93–95. doi:10.2307/1522637. JSTOR 1522637.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (8–14 September 1996). "Pre- and protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". XIII U. I. S. P. P. Congress Proceedings. 5. Lanka Library: 277–285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Geiger, Wilhelm (July 1930). "The Trustworthiness of the Mahavamsa". The Indian Historical Quarterly. 6 (2). Digital Library & Museum of Buddhist Studies: 205–228.

- Indrapala, K. (1969). "Early Tamil Settlements in Ceylon". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 13. JSTOR: 43–63. JSTOR 43483465.

- Kennedy, K. A. R.; Disotell, Todd; Roertgen, W. J.; Chiment, J.; Sherry, J. (1986). "Biological anthropology of Upper Pleistocene Hominids from Sri Lanka: Batadomba Lena and Beli Lena Caves". Ancient Ceylon. 6.

- Paranavitana, S. (1936). "Two Royal Titles of the Early Sinhalese, and the Origin of Kingship in Ancient Ceylon". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 68 (3). JSTOR: 443–462. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0007725X. JSTOR 25201355.