Bladder cancer

| Bladder cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. The white in the bladder is contrast. | |

| Specialty | Oncology, urology |

| Symptoms | Blood in the urine, pain with urination[1] |

| Usual onset | 65 to 84 years old[2] |

| Types | Transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma[1] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, family history, prior radiation therapy, frequent bladder infections, certain chemicals[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Cystoscopy with tissue biopsies[1] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rates ~77% (US)[2] |

| Frequency | 549,000 new cases (2018)[3] |

| Deaths | 200,000 (2018)[3] |

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder.[1] Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain.[1] It is caused when epithelial cells that line the bladder become malignant.[4]

Risk factors for bladder cancer include smoking, family history, prior pelvic radiation therapy, frequent bladder infections, and exposure to certain chemicals.[1] The most common type is transitional cell carcinoma.[1] Other types include squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.[1] Diagnosis is typically by cystoscopy with tissue biopsies.[5] Staging of the cancer is determined by transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) and medical imaging.[1][6][7]

Treatment depends on the stage of the cancer.[1] It may include some combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy.[1] Surgical options may include transurethral resection, partial or complete removal of the bladder, or urinary diversion.[1] The typical five-year survival rates in the United States is 77%, Canada is 75%, and Europe is 68%.[2][8][9]

Bladder cancer, as of 2018, affected about 1.6 million people globally with 549,000 new cases and 200,000 deaths.[3] Age of onset is most often between 65 and 84 years of age.[2] Males are more often affected than females, with the lifetime risk in males being 1.1% and 0.27% in females.[10][2] In 2018, the highest rate of bladder cancer occurred in Southern and Western Europe followed by North America with rates of 15, 13, and 12 cases per 100,000 people.[3] The highest rates of bladder cancer deaths were seen in Northern Africa and Western Asia followed by Southern Europe.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The most common symptom of bladder cancer is visible blood in the urine (haematuria) despite painless urination. This affects around 75% of people eventually diagnosed with the disease.[11] Some instead have "microscopic haematuria" – small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be seen under a microscope during urinalysis – pain while urinating, or no symptoms at all (their tumors are detected during unrelated medical imaging).[11][12] Less commonly, a tumor can block the flow of urine into the bladder, causing pain along the flank of the body (between the ribs and the hips).[13] Most people with blood in the urine do not have bladder cancer; up to 22% of those with visible haematuria and 5% with microscopic haematuria are diagnosed with the disease.[11] Women with bladder cancer and haematuria are often misdiagnosed with urinary tract infections, delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment.[12]

Around 3% of people with bladder cancer have tumors that have already spread (metastasized) outside the bladder at the time of diagnosis.[14] Bladder cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs, liver, and nearby lymph nodes; tumors cause different symptoms in each location. People whose cancer has metastasized to the bones most often experience bone pain or bone weakness that increases the risk of fractures. Lung tumors can cause persistent cough, coughing up blood, breathlessness, or recurrent chest infections. Cancer that has spread to the liver can cause general malaise, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain or swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and skin itch. Spread to nearby lymph nodes can cause pain and swelling around the affected lymph nodes, typically in the abdomen or groin.[15]

Diagnosis

[edit]Those suspected of having bladder cancer can undergo several tests to assess the presence and extent of any tumors. First, many undergo a physical examination that can involve a digital rectal exam and pelvic exam, where a doctor feels the pelvic area for unusual masses that could be tumors.[16] Severe bladder tumors often shed cells into the urine; these can be detected by urine cytology, where cells are collected from a urine sample, and viewed under a microscope.[16][17] Cytology can detect around two thirds of high-grade tumors, but detects just 1 in 8 low-grade tumors.[18] Additional urine tests can be used to detect molecules associated with bladder cancer. Some detect the proteins bladder tumor antigen or NMP22 that tend to be elevated in the urine of those with bladder cancer; some detect mRNA of tumor-associated genes; some use fluorescence microscopy to detect cancerous cells more sensitively than regular cytology.[18]

Many also undergo cystoscopy, wherein a flexible camera is threaded up the urethra and into the bladder to visually inspect for cancerous tissue.[16] Cystoscopy is most sensitive to papillary tumors (tumors with a finger-like shape that grow into the urine-holding part of the bladder); it is less sensitive to small, low-lying carcinoma in situ (CIS).[19] CIS detection is improved by blue light cystoscopy, where a dye (hexaminolevulinate) that accumulates in cancer cells is injected into the bladder during cystoscopy. The dye fluoresces when the cystoscope shines blue light on it, allowing for more sensitive detection of small tumors.[16][19]

The upper urinary tract (ureters and kidney) is also imaged for tumors that could cause blood in the urine. This is typically done by injecting a dye into the blood that the kidneys will filter into the urinary tract, then imaging by computed tomography scanning. Those whose kidneys are not functioning well enough to filter the dye may instead be scanned by magnetic resonance imaging.[13] Alternatively, the upper urinary tract can be imaged with ultrasound.[16]

Suspected tumors are removed by threading a device up the urethra in a process called "transurethral resection of bladder tumor" (TURBT). All tumors are removed, as well as a piece of the underlying bladder muscle. Removed tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine if it is cancerous.[16][20] If the tumor is removed incompletely, or is determined to be particularly high risk, a repeat TURBT is performed 4 to 6 weeks later to detect and remove any additional tumors.[20]

Classification

[edit]Bladder tumors are classified by their appearance under the microscope, and by their cell type of origin. Over 90% of bladder tumors arise from the cells that form the bladder's inner lining, called urothelial cells or transitional cells; the tumor is then classified as urothelial cancer or transitional cell cancer.[21][22] Around 5% of cases are squamous cell cancer (from a rarer cell in the bladder lining), particularly common in places with schistosomiasis.[22] Up to 2% of cases are adenocarcinoma (from mucus-producing gland cells).[22] The remaining cases are sarcomas (from the bladder muscle) or small-cell cancer (from neuroendocrine cells), both of which are relatively rare.[22]

The pathologist also grades the tumor sample based on how distinct the cancerous cells look from healthy cells. Bladder cancer is divided into either low-grade (more similar to healthy cells) or high-grade (less similar).[21]

Staging

[edit]

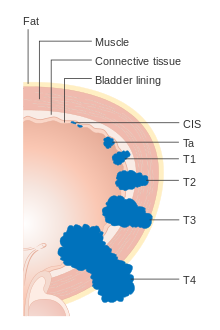

Each bladder cancer case is assigned a stage based on the TNM system defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.[21] A tumor is assigned three scores based on the extent of the primary tumor (T), its spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), and metastasis to distant sites (M).[23] The T score represents the extent of the original tumor: Ta or Tis for tumors that are confined to the innermost layer of the bladder; T1 for tumors that extend into the bladder's connective tissue; T2 for extension into the muscle; T3 for extension through the muscle into the surrounding fatty tissue; and T4 for extension fully outside the bladder.[23] The N score represents spread to nearby lymph nodes: N0 for no spread; N1 for spread to a single nearby lymph node; N2 for spread to several nearby lymph nodes; N3 for spread to more distant lymph nodes outside the pelvis.[23] The M score designates spread to more distant organs: M0 for a tumor that has not spread; M1 to one that has.[23] The TNM scores are combined to determine the cancer case's stage on a scale of 0 to 4, with a higher stage representing a more extensive cancer with a poorer prognosis.[14]

Around 75% of cases are confined to the bladder at the time of diagnosis (T scores: Tis, Ta, or T1), and are called non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Around 18% have tumors that have spread into the bladder muscle (T2, T3, or T4), and are called muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Around 3% have tumors that have spread to organs far from the bladder, and are called metastatic bladder cancer. Those with more extensive tumor spread tend to have a poorer prognosis.[14]

| Stage | T | N | M | 5-year survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis/Ta | N0 | M0 | 96% |

| 1 | T1 | N0 | M0 | 90% |

| 2 | T2 | N0 | M0 | 70% |

| 3 | T3 | N0 | M0 | 50% |

| 3 | Any T | N1-3 | M0 | 36% |

| 4 | Any T | Any N | M1 | 5% |

Treatment

[edit]The treatment of bladder cancer depends on the tumor's shape, size, and location, as well as the affected person's health and preferences.

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

[edit]NMIBC is primarily treated by surgically removing all tumors by TURBT in the same procedure used to collect biopsy tissue for diagnosis.[25][26] For those with a relatively low risk of tumors recurring, a single dose of chemotherapy (mitomycin C, epirubicin, or gemcitabine) injected into the bladder within 24 hours of TURBT reduces the risk of tumor occurrence by about 39%.[27] Those with higher risk are instead treated with bladder injections of the BCG vaccine (a live bacterial vaccine, traditionally used for tuberculosis), administered weekly for six weeks. This nearly halves the rate of tumor recurrence.[25] Recurrence risk is further reduced by a series of "maintenance" BCG injections, given regularly for at least a year.[25][28] Those whose tumors recur may receive a second round of BCG injections.[25] Tumors that do not respond to BCG may be treated with the alternative immune stimulants nadofaragene firadenovec (sold as "Adstiladrin", a gene therapy that makes bladder cells produce an immunostimulant protein), nogapendekin alfa inbakicept ("Anktiva", a combination of immunostimulant proteins), or pembrolizumab ("Keytruda", an immune checkpoint inhibitor).[29]

People whose tumors continue to grow are often treated with surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding organs, called radical cystectomy.[30] The bladder, several adjacent lymph nodes, the lower ureters, and nearby genital organs – in men the prostate and seminal vesicles; in women the uterus and part of the vaginal wall – are all removed.[30] Surgeons construct a new way for urine to leave the body. The most common method is by ileal conduit, where a piece of the ileum (part of the small intestine) is removed and used to transport urine from the ureters to a new surgical opening (stoma) in the abdomen. Urine drains passively into an ostomy bag worn outside the body, which can be emptied regularly by the wearer.[31] Alternatively, one can have a continent urinary diversion, where the ureters are attached to a piece of ileum that includes the valve between the small and large intestine; this valve naturally closes, allowing urine to be retained in the body rather than in an ostomy bag. The affected person empties the new urine reservoir serveral times each day by self-catheterization – passing a narrow tube through the stoma.[32][33] Some can instead have the piece of ileum attached directly to the urethra, allowing the affected person to urinate through the urethra as they would pre-surgery – although without the original bladder nerves, they will no longer have the urge to urinate when the urine reservoir is full.[34]

Radical cystectomy has both immediate and lifelong side effects. It is common for those recovering from surgery to experience gastrointestinal problems (29% of those who underwent radical cystectomy), infections (25%), and other issues with the surgical wound (15%).[35] Around 25% of those who undergo the surgery end up readmitted to the hospital within 30 days; up to 2% die within 30 days of the surgery.[35] Rerouting the ureters can also cause permanent metabolic issues. The piece of ileum used to reroute urine flow can absorb more ammonium chloride from the urine than the original bladder would, resulting in metabolic acidosis, which can be treated with sodium bicarbonate. Shortening the small intestine can result in reduced vitamin B12 absorption, which can be treated with oral vitamin B12 supplementation.[35] Issues with the new urine system can cause urinary retention, which can damage the ureters and kidneys and increase one's risk of urinary tract infection.[35]

Those not well enough or unwilling to undergo radical cystectomy may instead benefit from further bladder injections of chemotherapy – mitomycin C, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or valrubicin – or intravenous injection of pembrolizumab.[25] Around 1 in 5 people with NMIBC will eventually progress to MIBC.[36]

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

[edit]Most people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer are treated with radical cystectomy, which cures around half of those affected.[33] Treating with chemotherapy prior to surgery (called "neoadjuvant therapy") using a cisplatin-containing drug combination (gemcitabine plus cisplatin; or methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) improves survival an addition 5 to 10%.[33][37]

Those with certain types of lower-risk disease may instead receive bladder-sparing therapy. People with just a single tumor at the back of the bladder can undergo partial cystectomy, with the tumor and surrounding area removed, and the bladder repaired.[33] Those with no CIS or urinary blockage may undergo TURBT to remove visible tumors, followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy; around two thirds of these people are permanently cured.[33] After treatment, surveillance tests – urine and blood tests, and MRI or CT scans – are done every three to six months to look for evidence that tumors may be recurring. Those who have retained their bladder also receive cystoscopies to look for additional bladder tumors.[38] Recurrent bladder tumors are treated with radical cystectomy. Tumor recurrences elsewhere are treated as metastatic bladder cancer.[33]

Metastatic disease

[edit]The standard of care for metastatic bladder cancer is combination treatment with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine.[39] The average person on this combination survives around a year, though 15% experience remission, with survival over five years.[40][39] Around half of those with metastatic bladder cancer are in too poor health to receive cisplatin. They instead receive the related drug carboplatin along with gemcitabine; the average person on this regimen survives around 9 months.[40] Those whose disease responds to chemotherapy benefit from switching to immune checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab or atezolizumab ("Tecentriq") for long-term maintenance therapy.[41] Immune checkpoint inhibitors are also commonly given to those whose tumors do not respond to chemotherapy, as well as those in too poor health to receive chemotherapy.[42]

Those whose tumors continue to grow after platinum chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors can receive the antibody drug conjugate enfortumab vedotin ("Padcev", targets tumor cells with the protein nectin-4).[42][43] Enfortumab vedotin in combination with pembrolizumab can also be used as a first-line therapy in place of chemotherapy.[42] Those with genetic alterations that activate the proteins FGFR2 or FGFR3 (around 20% of those with metastatic bladder cancer) can also benefit from the FGFR inhibitor erdafitinib ("Balversa").[42]

Bladder cancer that continues growing can be treated with second-line chemotherapies. Vinflunine is used in Europe, while paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed are used in the United States; only a minority of those treated improve on these therapies.[44]

People with bone metastasis should receive bisphosphonates or denosumab to prevent skeletal related events (e.g. fractures, spinal cord compression, bone pain).[45]

Surveillance and response

[edit]Contrast enhanced CT is used to monitor lung, liver, and lymph node metastases. A bone scan is used to detect and monitor bone metastasis.[46] Treatment response is measured using the Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) into one of the following groups; response (complete or partial), stable disease and progressive disease.[47]

Causes

[edit]Bladder cancer is caused by changes to the DNA of bladder cells that result in those cells growing uncontrollably.[48] These changes can be random, or can be induced by exposure to toxic substances such as those from consuming tobacco.[49] Genetic damage accumulates over many years, eventually disrupting the normal functioning of bladder cells and causing them to grow uncontrollably into a lump of cells called a tumor.[48] Cancers cells accumulate further DNA changes as they multiply, which can allow the tumor to evade the immune system, resist regular cell death pathways, and eventually spread to distant body sites. The new tumors that form in various organs damage those organs, eventually causing the death of the affected person.

Smoking

[edit]Tobacco smoking is the main contributor to bladder cancer risk; around half of bladder cancer cases are estimated to be caused by smoking.[50][51] Tobacco contains carcinogenic molecules that enter the blood and are filtered by the kidneys into the urine. There they can cause damage to the DNA of bladder cells, eventually leading to cancer.[52] Bladder cancer risk rises both with number of cigarettes smoked per day, and with duration of smoking habit.[51] Those who smoke also tend to have worse courses of bladder cancer, with an increased risk of treatment failure, metastasis, and death.[53] The risk of developing bladder cancer decreases in those who quit smoking, falling up to 30% after five years of smoking abstention.[54] Cancer risk continues to fall over time with smoking abstention, but never returns to the level of those who have never smoked.[51] Because development of bladder cancer takes many years, it is not yet known if use of electronic cigarettes carries the same risk as smoking tobacco; however, those who use electronic cigarettes have higher levels of some urinary carcinogens than those who do not.[55]

Occupational exposure

[edit]Up to 10% of bladder cancer cases are caused by workplace exposure to toxic chemicals.[56] Exposure to certain aromatic amines, namely benzidine, beta-naphthylamine, and ortho-toluidine used in the metalworking and dye industries, can increase the risk of bladder cancer in metalworkers, dye producers, painters, printers, hairdressers, and textiles workers.[57][58] The International Agency for Research on Cancer further classifies rubber processing, aluminum production, and firefighting as occupations that increase one's risk of developing bladder cancer.[57] Exposure to arsenic – either through workplace exposure or through drinking water in places where arsenic naturally contaminates groundwater – is also commonly linked to bladder cancer risk.[57]

Medical conditions

[edit]Chronic bladder infections can increase one's risk of developing bladder cancer. Most prominent is schistosomiasis, in which the eggs of the flatworm Schistosoma haematobium can become lodged in the bladder wall, causing chronic bladder inflammation and repeated bladder infections.[59] In places with endemic schistosomiasis, up to 16% of bladder cancer cases are caused by prior Schistosoma infection.[59] Worms can be cleared by treatment with praziquantel, which reduces bladder cancer cases in schistosomiasis endemic areas.[59][60] Similarly, those with long-term indwelling catheters are at risk for repeated urinary tract infections, and have increased risk of developing bladder cancer.[61]

Some medical treatments are also known to increase bladder cancer risk. As many as 16% of those treated with the chemotherapeutic cyclophosphamide go on to develop bladder cancer within 15 years of their treatment.[62] Similarly, those treated with pelvic radiation (typically for prostate or cervical cancer) are at increased risk of developing bladder cancer five to 15 years after treatment.[62] Long-term use of the medication pioglitazone for type 2 diabetes may increase bladder cancer risk.[63]

Genetics

[edit]Bladder cancer does not typically run in families;[57] 4% of those diagnosed with bladder cancer have a parent or sibling with the disease.[64] The exception is in families with Lynch syndrome or Cowden disease, which have increased risk of developing several cancers, including bladder cancer.[63]

Large population studies have identified several gene variants that each slightly increase bladder cancer risk. Most of these are variants in genes involved in metabolism of carcinogens (NAT2, GSTM1, and UGT1A6), controlling cell growth (TP63, CCNE1, MYC, and FGFR3), or repairing DNA damage (NBN, XRCC1 and 3, and ERCC2, 4, and 5).[57]

Diet and lifestyle

[edit]Several studies have examined the impact of various lifestyle factors on the risk of developing bladder cancer. A 2018 summary of evidence from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research concluded that there is "limited, suggestive evidence" that consumption of tea, and a diet high in fruits and vegetables reduce a person's risk of developing bladder cancer. They also considered available data on exercise, body fat, and consumption of dairy, red meat, fish, grains, legumes, eggs, fats, soft drinks, alcohol, juices, caffeine, sweeteners, and various vitamins and minerals; for each they found insufficient data to link the lifestyle factor to bladder cancer risk.[65][66] Several other studies have indicated a slight increased risk of developing bladder cancer in those who are overweight or obese, as well as a slight decrease in risk for those who undertake high levels of physical activity.[65] Several studies have investigated a link between levels of fluid intake and bladder cancer risk – testing the theory that high fluid intake dilutes toxins in the urine and removes them through the body through more frequent urination – but have had inconsistent results, and a relationship remains unclear.[65]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The most common sites for bladder cancer metastases are the lymph nodes, bones, lung, liver, and peritoneum.[67] The most common sentinel lymph nodes draining bladder cancer are obturator and internal iliac lymph nodes. The location of lymphatic spread depends on the location of the tumors. Tumors on the superolateral bladder wall spread to external iliac lymph nodes. Tumors on the neck, anterior wall and fundus spread commonly to the internal iliac lymph nodes.[68] From the regional lymph nodes (i.e. obturator, internal and external lymph nodes) the cancer spreads to distant sites like the common iliac lymph nodes and paraaortic lymph nodes.[69] Skipped lymph node lesions are not seen in bladder cancer.[68]

Mutations in FGFR3, TP53, PIK3CA, KDM6A, ARID1A, KMT2D, HRAS, TERT, KRAS, CREBBP, RB1 and TSC1 genes may be associated with some cases of bladder cancer.[70][71][72]

Deletions of parts or whole of chromosome 9 is common in bladder cancer.[73] Low grade cancer are known to harbor mutations in RAS pathway and the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene, both of which play a role in the MAPK/ERK pathway. p53 and RB gene mutations are implicated in high-grade muscle invasive tumors.[74] Eighty nine percent of muscle invasive cancers have mutations in chromatin remodeling and histone modifying genes.[75]

Muscle invasive bladder cancer are heterogeneous in nature. In general, they can be genetically classified into basal and luminal subtypes. Basal subtype show alterations involving RB and NFE2L2 and luminal type show changes in FGFR3 and KDM6A genes.[76] Basal subtype are subdivided into basal and claudin low-type group and are aggressive and show metastasis at presentation, however they respond to platinum based chemotherapy. Luminal subtype can be subdivided into p53-like and luminal. p53-like tumors of luminal subtype although not as aggressive as basal type, show resistance to chemotherapy[77]

Prognosis

[edit]People with non-muscle invasive tumors have a favorable outcome (5-year survival is 95% vs. 69% of muscle invasive bladder cancer).[78][79] However, 70% of them will have a recurrence after initial treatment with 30% of them presenting with muscle invasive disease.[80] Recurrence and progression to a higher disease stage have a less favorable outcome.[81]

Survival after radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection is dependent on the pathological stage. If the disease has not spread to the lymph node and is limited to the bladder (T1 or T2, N0) the 5-year survival is 78%. If it has spread locally around the region of the bladder with no lymph node involved (T3, N0) then the 5-year survival drops to 47%. In disease with lymph node spread (N+, irrespective of T stage) the 5-year survival is 31%. Locally advanced and metastatic disease drastically decreases survival, with a median survival of 3–6 months without chemotherapy. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy has increased the median survival to 15-months. However, the 5-year survival is still 15%.[82]

There are several prognostic factors which determine cancer specific survival after radical cystectomy. Factor with detrimental effect of cancer specific survival are old age, higher tumor grade and pathological stage, lymph node metastasis, presence of lymphovascular invasion and positive soft tissue margin.[83] Lymph node density (positive lymph nodes/total lymph nodes observed in the specimen from surgery) is a predictor of survival in lymph node positive disease. Higher the density lower is the survival.[84]

Quality of life

[edit]After radical cystectomy, urinary and sexual function remain inferior to the general population. People who have a neobladder have better emotional function and body image compared with ones with cutaneous diversion (who need to wear a bag to collect urine over their abdomen).[85] Social factors such as family, relationships, health and finances contribute significantly for determining good quality of life in people who have been diagnosed with bladder cancer.[86]

A high percentage of people with bladder cancer have anxiety and depression.[87] People who are young, single and have advanced clinical disease have a high risk for getting diagnosed with a psychiatric illness post-treatment. People with psychiatric illness post treatment seem to have worse cancer specific and overall survival.[88][89]

Epidemiology

[edit]| Rank | Country | Overall | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lebanon | 25 | 40 | 9 |

| 2 | Greece | 21 | 40 | 4 |

| 3 | Denmark | 18 | 29 | 8 |

| 4 | Hungary | 17 | 27 | 9 |

| 5 | Albania | 16 | 27 | 6 |

| 5 | Netherlands | 16 | 26 | 8 |

| 7 | Belgium | 16 | 27 | 6 |

| 8 | Italy | 15 | 27 | 6 |

| 9 | Germany | 15 | 26 | 6 |

| 10 | Spain | 15 | 27 | 6 |

Around 500,000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year, and 200,000 die of the disease.[27] This makes bladder cancer the tenth most commonly diagnosed cancer, and the thirteenth cause of cancer deaths.[60] Bladder cancer is most common in wealthier regions of the world, where exposure to certain carcinogens is highest. It is also common in places where schistosome infection is common, such as North Africa.[60]

Bladder cancer is much more common in men than women; around 1.1% of men and 0.27% of women develop bladder cancer.[12] This makes bladder cancer the sixth most common cancer in men, and the seventeenth in women.[93] When women are diagnosed with bladder cancer, they tend to have more advanced disease and consequently a poorer prognosis.[93] This difference in outcomes is attributed to numerous factors such as, difference in carcinogen exposure, genetics, social and quality of care.[94] One of the common signs of bladder cancer is hematuria and is quite often misdiagnosed as urinary tract infection in women, leading to a delay in diagnosis.[94] Smoking can only partially explain this higher rates in men in western hemisphere.[95] In Africa, men are more prone to do field work and are exposed to infection with Schistosoma, this may explain to a certain extent the gap in incidence of squamous cell cancers in areas where bladder cancer is endemic.[95]

As with most cancers, bladder cancer is more common in older people; the average person with bladder cancer is diagnosed at age 73.[96] 80% of those diagnosed with bladder cancer are 65 or older; 20% are 85 or older.[97]

Veterinary medicine

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Bladder Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Cancer of the Urinary Bladder - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Bladder Cancer Factsheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Heyes S.M., Prior K.N., Whitehead D., Bond M.J. Toward an Understanding of Patients' and Their Partners' Experiences of Bladder Cancer. Cancer Nurs.. 2020;43(5):E254-E263. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000718

- ^ "Bladder Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "EAU Guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer". Uroweb.

- ^ "Bladder Cancer - Stages and Grades". Cancer.Net. 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Bladder cancer". World Cancer Research Fund. 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Survival statistics for bladder cancer - Canadian Cancer Society". www.cancer.ca.

- ^ Lenis, Andrew T.; Lec, Patrick M.; Chamie, Karim; Mshs, Md (17 November 2020). "Bladder Cancer: A Review". JAMA. 324 (19): 1980–1991. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17598. PMID 33201207.

- ^ a b c Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Clinical Presentation".

- ^ a b c Lenis, Lec & Chamie 2020, p. 1981.

- ^ a b Hahn 2022, "Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Workup".

- ^ a b c Hahn 2022, "Staging and Outcomes by Stage".

- ^ "Symptoms of Metastatic Bladder Cancer". Cancer Research UK. 14 March 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tests for Bladder Cancer". American Cancer Society. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Diagnosis and Screening".

- ^ a b Ahmadi, Duddalwar & Daneshmand 2021, "Urine Cytology and Other Urine-Based Tumor Markers.

- ^ a b Ahmadi, Duddalwar & Daneshmand 2021, pp. 532–533.

- ^ a b Lenis, Lec & Chamie 2020, p. 1982.

- ^ a b c Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Tissue-Based Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer".

- ^ a b c d "Types of Bladder Cancer". Cancer Research UK. 22 September 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Stages of bladder cancer". Cancer Research UK. 22 September 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Hahn 2022, "Figure 86-2".

- ^ a b c d e Hahn 2022, "Early-Stage Disease".

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "TURBT and En Bloc Resection of Bladder Tumor".

- ^ a b Lenis, Lec & Chamie 2020, p. 1980.

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Intravesical Therapy for NMIBC".

- ^ "Treatment of Bladder Cancer, Based on Stage and Other Factors". American Cancer Society. 1 May 2024.

- ^ a b Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Radical Cystectomy".

- ^ "Surgery to Remove the Bladder (Cystectomy)". Cancer Research UK. 11 November 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ "Continent Urinary Diversion (Internal Pouch)". Cancer Research UK. 24 November 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Hahn 2022, "Muscle-Invasive Disease".

- ^ "Bladder Reconstruction (Neobladder)". Cancer Reseaerch UK. 25 November 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d Lenis, Lec & Chamie 2020, p. 1986.

- ^ Teoh et al. 2022, p. 280.

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Perioperative Systemic Therapy".

- ^ "Living as a Bladder Cancer Survivor". American Cancer Society. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ a b Compérat et al. 2022, pp. 1717–1718.

- ^ a b Hahn 2022, "Metastatic Disease".

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Bladder Cancer".

- ^ a b c d Lopez-Beltran et al. 2024, "Treatment of Metastatic Bladder Cancer".

- ^ "Gilead Pulls Trodelvy's Approval in Bladder Cancer after Trial Flop, FDA Discussions". Fierce Pharma. 18 October 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Smith et al. 2020, p. 1398.

- ^ Aapro M, Abrahamsson PA, Body JJ, Coleman RE, Colomer R, Costa L, et al. (March 2008). "Guidance on the use of bisphosphonates in solid tumours: recommendations of an international expert panel". Annals of Oncology. 19 (3): 420–32. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm442. PMID 17906299.

- ^ Heidenreich A, Albers P, Classen J, Graefen M, Gschwend J, Kotzerke J, et al. (2010). "Imaging studies in metastatic urogenital cancer patients undergoing systemic therapy: recommendations of a multidisciplinary consensus meeting of the Association of Urological Oncology of the German Cancer Society". Urologia Internationalis. 85 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1159/000318985. PMID 20693823.

- ^ Llewelyn R. "Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia.

- ^ a b "What Causes Bladder Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "How Does Cancer Start". Cancer Research UK. 6 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Hahn 2022, "Risk Factors".

- ^ a b c Jubber et al. 2023, "3.2.1. Smoking".

- ^ "Causes – Bladder Cancer". National Health Service. 1 July 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Lobo et al. 2022, "3.2.1. Tobacco Smoking".

- ^ van Hoogstraten et al. 2023, pp. 291–292.

- ^ van Hoogstraten et al. 2023, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Lobo et al. 2022, "3.2.2. Occupational carcinogen exposure".

- ^ a b c d e van Hoogstraten et al. 2023, p. 295.

- ^ Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Occupational exposure".

- ^ a b c van Hoogstraten et al. 2023, p. 296.

- ^ a b c Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Epidemiology".

- ^ Lopez-Beltran et al. 2024, "Epidemiology".

- ^ a b Mossanen 2021, p. 449.

- ^ a b Hahn 2022, "Clinical Epidemiology and Risk Factors".

- ^ Jubber et al. 2023, "3.2. Risk Factors for BC".

- ^ a b c van Hoogstraten et al. 2023, p. 293.

- ^ "Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Bladder Cancer" (PDF). World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. 2018. p. 20. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, Fennessy FM, Taplin ME, Van den Abbeele AD (January 2011). "Metastatic pattern of bladder cancer: correlation with the characteristics of the primary tumor". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 196 (1): 117–22. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5036. PMID 21178055.

- ^ a b Mao Y, Hedgire S, Prapruttam D, Harisinghani M (16 September 2014). "Imaging of Pelvic Lymph Nodes". Current Radiology Reports. 2 (11). doi:10.1007/s40134-014-0070-z.

- ^ Shankar PR, Barkmeier D, Hadjiiski L, Cohan RH (October 2018). "A pictorial review of bladder cancer nodal metastases". Translational Andrology and Urology. 7 (5): 804–813. doi:10.21037/tau.2018.08.25. PMC 6212631. PMID 30456183.

- ^ "Cancer Genetics Browser". cancer.sanger.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 109800

- ^ Zhang X, Zhang Y (September 2015). "Bladder Cancer and Genetic Mutations". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 73 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1007/s12013-015-0574-z. PMID 27352265. S2CID 14316154.

- ^ "Bladder cancer". Genetics Home Reference.

- ^ Ahmad I, Sansom OJ, Leung HY (May 2012). "Exploring molecular genetics of bladder cancer: lessons learned from mouse models". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 5 (3): 323–32. doi:10.1242/dmm.008888. PMC 3339826. PMID 22422829.

- ^ Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE (July 2016). "The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours" (PDF). European Urology. 70 (1): 106–119. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. PMID 26996659. S2CID 3756845.

- ^ Choi W, Ochoa A, McConkey DJ, Aine M, Höglund M, Kim WY, et al. (September 2017). "Genetic Alterations in the Molecular Subtypes of Bladder Cancer: Illustration in the Cancer Genome Atlas Dataset". European Urology. 72 (3): 354–365. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.010. PMC 5764190. PMID 28365159.

- ^ Choi W, Czerniak B, Ochoa A, Su X, Siefker-Radtke A, Dinney C, McConkey DJ (July 2014). "Intrinsic basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer". Nature Reviews. Urology. 11 (7): 400–10. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2014.129. PMID 24960601. S2CID 24723395.

- ^ Siddiqui MR, Grant C, Sanford T, Agarwal PK (August 2017). "Current clinical trials in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer". Urologic Oncology. 35 (8): 516–527. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.06.043. PMC 5556973. PMID 28778250.

- ^ "Bladder Cancer - Statistics". Cancer.Net. 25 June 2012.

- ^ Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Feldman AS (July 2009). "Bladder cancer". Lancet. 374 (9685): 239–49. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60491-8. PMID 19520422. S2CID 40417997.

- ^ van der Heijden AG, Witjes JA (September 2009). "Recurrence, Progression, and Follow-Up in Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer". European Urology Supplements. 8 (7): 556–562. doi:10.1016/j.eursup.2009.06.010.

- ^ Tyson MD, Chang SS, Keegan KA (2016). "Role of consolidative surgical therapy in patients with locally advanced or regionally metastatic bladder cancer". Bladder. 3 (2): e26. doi:10.14440/bladder.2016.89. PMC 5336315. PMID 28261632.

- ^ Zhang L, Wu B, Zha Z, Qu W, Zhao H, Yuan J (July 2019). "Clinicopathological factors in bladder cancer for cancer-specific survival outcomes following radical cystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 19 (1): 716. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5924-6. PMC 6642549. PMID 31324162.

- ^ Ku JH, Kang M, Kim HS, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Kim HH (June 2015). "Lymph node density as a prognostic variable in node-positive bladder cancer: a meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 15: 447. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1448-x. PMC 4450458. PMID 26027955.

- ^ Yang LS, Shan BL, Shan LL, Chin P, Murray S, Ahmadi N, Saxena A (September 2016). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer". Surgical Oncology. 25 (3): 281–97. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2016.05.027. PMID 27566035.

- ^ Somani BK, Gimlin D, Fayers P, N'dow J (November 2009). "Quality of life and body image for bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy and urinary diversion--a prospective cohort study with a systematic review of literature". Urology. 74 (5): 1138–43. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.087. PMID 19773042.

- ^ Vartolomei L, Ferro M, Mirone V, Shariat SF, Vartolomei MD (July 2018). "Systematic Review: Depression and Anxiety Prevalence in Bladder Cancer Patients". Bladder Cancer. 4 (3): 319–326. doi:10.3233/BLC-180181. PMC 6087432. PMID 30112443.

- ^ David E (February 2017). "Psychiatric disorders worsen bladder cancer survival". www.healio.com. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Correa AF, Smaldone MC (August 2018). "Melancholia and cancer: The bladder cancer narrative". Cancer. 124 (15): 3080–3083. doi:10.1002/cncr.31402. PMID 29660788.

- ^ "Bladder cancer statistics". World Cancer Research Fund. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Greece Factsheet" (PDF). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ a b Dyrskjøt et al. 2023, "Introduction".

- ^ a b Marks P, Soave A, Shariat SF, Fajkovic H, Fisch M, Rink M (October 2016). "Female with bladder cancer: what and why is there a difference?". Translational Andrology and Urology. 5 (5): 668–682. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.03.22. PMC 5071204. PMID 27785424.

- ^ a b Hemelt M, Yamamoto H, Cheng KK, Zeegers MP (January 2009). "The effect of smoking on the male excess of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis and geographical analyses". International Journal of Cancer. 124 (2): 412–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.23856. PMID 18792102. S2CID 28518800.

- ^ Hahn 2022, "Introduction".

- ^ Mossanen 2021, p. 448.

- ^ Lipscomb, Victoria J. (2011). "Section XI Urogenital system. Chapter 116 Bladder. Bladder neoplasia". In Tobias, Karen M.; Johnston, Spencer A. (eds.). Veterinary Surgery. London: Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1990–1992. ISBN 9780323263375.

Works cited

[edit]- Ahmadi H, Duddalwar V, Daneshmand S (June 2021). "Diagnosis and Staging of Bladder Cancer". Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 35 (3): 531–541. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2021.02.004. PMID 33958149.

- Compérat E, Amin MB, Cathomas R, Choudhury A, De Santis M, Kamat A, Stenzl A, Thoeny HC, Witjes JA (November 2022). "Current best practice for bladder cancer: a narrative review of diagnostics and treatments". Lancet. 400 (10364): 1712–1721. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01188-6. PMID 36174585.

- Dyrskjøt L, Hansel DE, Efstathiou JA, Knowles MA, Galsky MD, Teoh J, Theodorescu D (October 2023). "Bladder cancer". Nat Rev Dis Primers. 9 (1): 58. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00468-9. PMC 11218610. PMID 37884563.

- Hahn NM (2022). "Chapter 86: Cancer of the Bladder and Urinary Tract". In Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (21st ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1264268504.

- Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L, Black PC, Compérat E, Kamat AM, Kiemeney L, Lawrentschuk N, Lerner SP, Meeks JJ, Moch H, Necchi A, Panebianco V, Sridhar SS, Znaor A, Catto JW, Cumberbatch MG (August 2023). "Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors". Eur Urol. 84 (2): 176–190. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.029. hdl:11573/1696425. PMID 37198015.

- Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K (November 2020). "Bladder Cancer: A Review". JAMA. 324 (19): 1980–1991. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17598. PMID 33201207.

- Lobo N, Afferi L, Moschini M, Mostafid H, Porten S, Psutka SP, Gupta S, Smith AB, Williams SB, Lotan Y (December 2022). "Epidemiology, Screening, and Prevention of Bladder Cancer". Eur Urol Oncol. 5 (6): 628–639. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2022.10.003. PMID 36333236.

- Lopez-Beltran A, Cookson MS, Guercio BJ, Cheng L (February 2024). "Advances in diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer". BMJ. 384: e076743. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076743. PMID 38346808.

- Mossanen M (June 2021). "The Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer". Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 35 (3): 445–455. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2021.02.001. PMID 33958144.

- Smith BA, Balar AV, Milowsky MI, Chen RC (2020). "Carcinoma of the Bladder". Abeloff's Clinical Oncology (6 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1382–1400. ISBN 978-0-323-47674-4.

- Teoh JY, Kamat AM, Black PC, Grivas P, Shariat SF, Babjuk M (May 2022). "Recurrence mechanisms of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer - a clinical perspective". Nat Rev Urol. 19 (5): 280–294. doi:10.1038/s41585-022-00578-1. PMID 35361927.

- van Hoogstraten LM, Vrieling A, van der Heijden AG, Kogevinas M, Richters A, Kiemeney LA (May 2023). "Global trends in the epidemiology of bladder cancer: challenges for public health and clinical practice". Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20 (5): 287–304. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00744-3. PMID 36914746.