United States federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

| Part of a series on the |

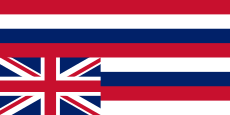

| Hawaiian sovereignty movement |

|---|

|

| Main issues |

| Governments |

| Historical conflicts |

| Modern events |

| Parties and organizations |

| Documents and ideas |

| Books |

Native Hawaiians are the Indigenous peoples of the Hawaiian Islands. Since the involvement of the United States in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, federal statutes have been enacted to address conditions of Native Hawaiians, with some feeling these should be formalized in the same manner of sovereignty as other Indigenous populations in the United States and Alaska Natives.[2][3] However, some controversy surrounds the proposal for formal recognition – many Native Hawaiian political organizations believe recognition might interfere with Hawaiian claims to independence as a constitutional monarchy through international law.[4][5]

Background

[edit]Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

[edit]

The ancestors of Native Hawaiians may have arrived in the Hawaiian Islands around 350 CE, from other areas of Polynesia.[6] By the time Captain Cook arrived, Hawaii had a well established culture with populations estimated to be between 400,000 and 900,000 people.[6] In the first one hundred years of contact with western civilization, due to disease and sickness, the Hawaiian population dropped by ninety percent with only 53,900 people in 1876.[6] American missionaries would arrive in 1820 and assume great power and influence.[6] While the United States and other nations formally recognized the Kingdom of Hawaii, American influence in Hawaii, with assistance from the United States Navy, took over the islands.[6] The Kingdom of Hawaii was overthrown beginning January 17, 1893 with a coup d'état orchestrated by American and European residents within the kingdom's legislature and assisted by the United States military.[6][7] While there was much opposition and many attempts to restore the kingdom, it became a territory of the US in 1898, without any input from Native Hawaiians.[6] Hawaii became a US state on March 18, 1959 following a referendum in which at least 93% of voters approved of statehood.

The US constitution recognizes Native American tribes as domestic, dependent nations with inherent rights of self-determination through the US government as a trust responsibility that was extended to include Inuit, Aleuts and Native Alaskans with the passing of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Though enactment of 183 federal laws over 90 years, the US has entered into an implicit, rather than explicit trust relationship that does not give formal recognition of a sovereign people the right of self-determination. Without an explicit law, Native Hawaiians may not be eligible for entitlements, funds and benefits afforded to other US Indigenous peoples.[8] Native Hawaiians are recognized by the US government through legislation with a unique status.[6]

Hawaiian Homelands and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs

[edit]In 1921, the Hawaiian Homelands Commission Act set aside 200,000 acres of land for the Hawaiian Homelands but only for those of at least fifty percent blood quantum.[6] It was meant to create some compensation for forced colonization of the Indigenous peoples, but in 1959 Hawaii was officially adopted as the fiftieth state of the US with the Statehood Admissions Act defining "Native Hawaiian" as any person descended from the aboriginal people of Hawaii, living there prior to 1778.[6] The Ceded lands (lands once owned by the Hawaiian kingdom monarchy) were transferred from the federal government to the State of Hawaii for the "betterment of the conditions of the native Hawaiians."[6] In 1978 the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) was created to manage that portion of the ceded lands allotted to Hawaiian Homelands, advance the lifestyle of Native Hawaiians, preserve Hawaiian culture and protect Native Hawaiian rights. Government funding has created programs, schools, scholarships and teaching curriculums through OHA.[6] Many of these organizations, agencies and trusts like OHA, have had a good deal of legal issues over the years. In the US Supreme court case Rice v. Cayetano, OHA was accused of violating the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution with voting provisions that were race-based. The court found for the plaintiff that OHA had violated the Fifteenth Amendment. OHA has also been questioned for programs and services to Hawaiians of less than the fifty percent required blood quantum (the minimum requirement to qualify for Hawaiian Homelands).[6]

The Apology Bill and the Akaka Bill

[edit]In the past decades, the growing frustration of Native Hawaiians over Hawaiian Homelands as well as the 100 year anniversary of the overthrow, pushed the Hawaiian sovereignty movement to the forefront of politics in Hawaii. In 1993, then-President Bill Clinton signed the United States Public Law 103-150, known as the "Apology Bill," for US involvement in the 1893 overthrow. The bill offers a commitment towards reconciliation.[6][9]

US census information shows there were approximately 401,162 Native Hawaiians living within the United States in the year 2000. Sixty percent live in the continental US with forty percent living in the State of Hawaii.[6] Between 1990 and 2000, those people identifying as Native Hawaiian had grown by 90,000 additional people, while the number of those identifying as pure Hawaiian had declined to under 10,000.[6]

Senator Daniel Akaka sponsored a bill in 2009 entitled the Native Hawaiian Government Reorganization Act of 2009 (S1011/HR2314) which would create the legal framework for establishing a Hawaiian government. The bill was supported by US President Barack Obama.[10] Even though the bill is considered a reconciliation process, it has not had that effect but has instead been the subject of much controversy and political fighting from many arenas. American opponents argue that congress is disregarding US citizens for special interests and sovereignty activists believe this will further erode their rights as the 1921 blood quantum rule of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act had done.[11] In 2011, a governor appointed committee began to gather and verify names of Native Hawaiians for the purpose of voting on a Native Hawaiian nation.[12]

In June 2014, the US Department of the Interior announced plans to hold hearings to establish the possibility of federal recognition of Native Hawaiians as an Indian tribe.[13][14]

Department of Interior procedure

[edit]The year of hearings found most speakers with strong opposition to the United States government's involvement in the Hawaiian sovereignty issue.[15]

On September 29, 2015, the United States Department of the Interior announced a procedure to recognize a Native Hawaiian government.[15][16] The Native Hawaiian Roll Commission was created to find and register Native Hawaiians.[17] The nine member commission with the needed expertise for verifying Native Hawaiian ancestry has prepared a roll of registered individuals of Hawaiian heritage.[18]

The nonprofit organization Na'i Aupuni will organize the constitutional convention and election of delegates using the roll which began collecting names in 2011. Kelii Akina, Chief Executive Officer of the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, filed suit to see the names on the roll and won, finding serious flaws. The Native Hawaiian Roll Commission has since purged the list of names of deceased persons as well as those whose address or e-mails could not be verified.

Akina again filed suit to stop the election because funding of the project comes from a grant from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and citing a United States Supreme Court case prohibiting the states from conducting race-based elections.[19]

In October 2015, a federal judge declined to stop the process from proceeding. The case was appealed with a formal emergency request to stop the voting until the appeal was heard but the request was denied.[20]

On November 24, the emergency request was made again to Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.[21] On November 27, Justice Kennedy stopped the election tallying or naming of any delegates.[citation needed] On an earlier United States Supreme Court case Rice v. Cayetano in 2000, Kennedy wrote, "Ancestry can be a proxy for race".

The decision did not stop the voting itself, and a spokesman for the Na'i Aupuni continued to encourage those eligible to vote before the end of the set deadline of November 30, 2015.[22]

The election was expected to have a cost of about $150,000, and voting was carried out by Elections America, a firm based in Washington D.C. The constitutional convention itself has an estimated cost of $2.6 million.[19]

See also

[edit]- Kahoʻolawe

- Walter Ritte

- List of Hawaiian sovereignty movement groups

- Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Legal status of Hawaii

- Aboriginal self-government in Canada

- Ethnic separatism

- Indigenous rights

- Self-determination

- National questions

References

[edit]- ^ Spencer, Thomas P. (1895). Kaua Kuloko 1895. Honolulu: Papapai Mahu Press Publishing Company. OCLC 19662315.

- ^ Amy E. Den Ouden; Jean M. O'Brien (2013). Recognition, Sovereignty Struggles, & Indigenous Rights in the United States: A Sourcebook. UNC Press Books. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-4696-0215-8.

- ^ United States of America Congressional Record 111th Congress, Vol. 155 – Part 7. Government Printing Office. pp. 8564–. GGKEY:1PYF5UE6TU0.

- ^ Donald L. Fixico (December 12, 2007). Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty. ABC-CLIO. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-57607-881-5.

- ^ David Eugene Wilkins; Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark (2011). American Indian Politics and the American Political System. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-4422-0387-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Joseph G. Ponterotto; J. Manuel Casas; Lisa A. Suzuki; Charlene M. Alexander (August 24, 2009). Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. SAGE Publications. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-1-4833-1713-7.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (May 20, 2009). Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, The: A Political, Social, and Military History: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-85109-952-8.

- ^ Davianna McGregor (2007). N_ Kua'_ina: Living Hawaiian Culture. University of Hawaii Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8248-2946-9.

- ^ Bendure, Friary, Glenda, Ned (2003), Oahu, Lonely Planet, p. 24, ISBN 978-1-74059-201-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jeff Campbell (September 15, 2010). Hawaii. Lonely Planet. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-74220-344-7.

- ^ Eva Bischoff; Elisabeth Engel (2013). Colonialism and Beyond: Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-643-90261-0.

- ^ Lyte, Brittany (September 16, 2015). "Native Hawaiian election set". The Garden island. The Garden Island. Retrieved October 6, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Grass, Michael (August 12, 2014). "As Feds Hold Hearings, Native Hawaiians Press Sovereignty Claims". Government Executive. Government Executive. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Office of the Secretary of the interior (June 18, 2014). "Interior Considers Procedures to Reestablish a Government-to-Government Relationship with the Native Hawaiian Community". US Department of the interior. US Government, Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ a b Lauer, Nancy Cook (September 30, 2015). "Interior Department announces procedure for Native Hawaiian recognition". Oahu Publications. West Hawaii Today. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Interior Proposes Path for Re-Establishing Government-to-Government Relationship with Native Hawaiian Community". Department of the Interior. Office of the Secretary of the Department of the interior. September 29, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Edward Hawkins Sisson (June 22, 2014). America the Great. Edward Sisson. p. 1490. GGKEY:0T5QX14Q22E.

- ^ Ariela Julie Gross (June 30, 2009). What Blood Won't Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America. Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-674-03797-7.

- ^ a b Rick, Daysog (October 6, 2015). "Critics: Hawaiian constitutional convention election process is flawed". Hawaii News Now. Hawaii News Now. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Fed Appeals Court Won't Stop Hawaiian Election Vote Count". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 19, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "Opponents Ask High Court to Block Native Hawaiian Vote Count". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "Supreme Court Justice Intervenes in Native Hawaiian Election". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 27, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bendure, Glenda (2003). Oahu. Melbourne Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet Pub. ISBN 978-1-74059-201-7.

- Bischoff, Eva (2013). Colonialism and beyond : race and migration from a postcolonial perspective. Zürich: Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-90261-0.

- Campbell, Jeff (2009). Hawaii. Footscray, Vic. London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74220-344-7.

- Fixico, Donald (2008). Treaties with American Indians : an encyclopedia of rights, conflicts, and sovereignty. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-881-5.

- McGregor, Davianna (2007). Nā Kua'āina living Hawaiian culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2946-9.

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). The encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars a political, social, and military history. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-952-8.

- Ouden, Amy (2013). Recognition, sovereignty struggles, & indigenous rights in the United States a sourcebook. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-0215-8.

- Wilkins, David (2011). American Indian politics and the American political system. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-0387-7.

Used multiple times as overarching referencing for the subject or section

- Ponterotto, Joseph (2010). Handbook of multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1412964326.

External links

[edit]- Kana'iolowalu Native Hawaiian Roll Commission website to register as a Native Hawaiian

- Naʻi Aupuni Office of Hawaiian Affairs funded constitutional convention organization

- Hawaiiankingdom.org Sovereignty organization

- Hawaii-nation.org Sovereignty organization

- Protestnaiaupuni.com Community Resistance Website

- Ahaalohaaina.com Pro Independence Movement