Belarusian nationalism

Belarusian nationalism refers to the belief that Belarusians should constitute an independent nation. Belarusian nationalism began emerging in the mid-19th century, during the January Uprising against the Russian Empire. Belarus first declared independence in 1917 as the Belarusian Democratic Republic, but was subsequently invaded and annexed by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1918, becoming part of the Soviet Union. Belarusian nationalists both collaborated with and fought against Nazi Germany during World War II, and protested for the independence of Belarus during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Belarusian nationalism has historically been divided into two groups; pro-western and pro-Russian. These different groups have continually sought to take control from the other since the early 1860s. These groups are additionally divided along religious lines, with Catholics belonging to the pro-western camp and Eastern Orthodox Christians belonging to the pro-Russian. Various historical attempts have been made to unite Belarus under a singular religion, including the Ruthenian Uniate Church before 1917 and Protestantism in the 1920s, though these efforts all fell flat.

In Belarus, Belarusian nationalism is a controversial position. The government of Alexander Lukashenko has vacillated between promoting pro-Russian Belarusian nationalism and unification with Russia. Pro-western Belarusian nationalists have been tied to Axis collaboration with Nazi Germany by the government in an effort to discredit the Belarusian opposition and legitimize Lukashenko's rule. The pro-western group has countered Lukashenko's claims by associating themselves with the Belarusian resistance during World War II.

Origins

[edit]Precedents

[edit]Certain Belarusian nationalists, among them Mikola Yermalovich, have cited the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as the first Belarusian state. This pseudohistorical theory, commonly referred to as Litvinism, emerged from efforts by the Russian Empire in order to propagate the idea of a Lithuania which was more favourable to Tsarist interests in the aftermath of the partitions of Poland. These ideas re-emerged as part of efforts by Józef Piłsudski to rationalise the annexation of Vilnius by the Second Polish Republic before being co-opted by Belarusian nationalists following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[2][3][4] Some members of the Belarusian opposition, among them Zianon Pazniak, have sought to cast Litvinism as a movement artificially inflated by the Russian government in an attempt to vilify Belarusian nationalism. Moreover, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, Belarusian scientists and members of the anti-Lukashenko opposition narrated that the Lithuanian capital Vilnius historically was Belarusian and was established by the Belarusians.[5][6][7][8][9]

Francysk Skaryna, a 16th-century book printer, has become a unifying figure of Belarusian nationalists since efforts began to establish his significance as a Belarusian figure in the 1920s. Skaryna, who was the first to translate the Bible into the "Simple speech" of the time, was initially rejected as a member of the "Polotsk bourgeoise" in the 1930s. However, following World War II, Skaryna's image saw a renaissance in Belarus, particularly in the face of unsuccessful efforts to transfer Polotsk to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1944. The 1969 film I, Francysk Skaryna additionally brought recognition of Skaryna as a uniquely Belarusian figure. In a 2002 poll, he was regarded as a prominent Belarusian by 61.6%, strongly leading against Yanka Kupala, who placed second with 41.7% of respondents calling him a prominent Belarusian.[10]

Another figure which has become associated with Belarusian nationalism is Tadeusz Kościuszko, leader of the Kościuszko Uprising. In the aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, recognition of Kościuszko, born near the southwestern Belarusian city of Kosava, as a Belarusian national hero began. Debate over the extent to which Kościuszko can be recognized as a Belarusian national hero has intensified since 2014, with monuments to Kościuszko being erected both within Belarus and by members of the Belarusian diaspora. In 2019, a claim by the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus that Kościuszko was Polish and American, rather than Belarusian, prompted widespread criticism and ridicule, leading the National Academy of Sciences to eventually walk back its former statement and note that he was a politician in Belarus, Poland, and the United States. Debate over Kościuszko's nationality has additional political dimensions, with pro-western groups generally taking the position of him being Belarusian and pro-Russian groups, among them the Belarusian government, casting him as Polish.[11]

Interest in the Belarusian nation and language among intellectuals began in the early 19th century, as part of the Belarusian national revival. Among the leading figures of this period were Jan Barszczewski, Jan Czeczot, and Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich, who developed the basis of the modern Belarusian language. Barszczewski and Czeczot were among the first to develop the idea of Belarusians as a group separate from Poles. At this time, however, Belarusian nationalism did not emerge; instead, two competing schools of thought variously sought to place Belarus alongside Russia or Poland. The former school was referred to as West-Rusism. Konstanty Kalinowski, himself a follower of the Polonophile section of Belarusian intelligentsia, was the first to promote the idea of Belarus as an independent nation. Counter to him were some of the Belarusian language's most prominent linguists, among them Yefim Karsky.[12]

Belarusian nationalists historically have placed blame on the 1839 dissolution of the Ruthenian Uniate Church during the Synod of Polotsk as having had a strongly detrimental effect on the Belarusian nation. However, historian Grigory Ioffe has debated this, noting that while a separation exists between those whose families historically held Catholic and Eastern Orthodox views and President Alexander Lukashenko has promoted anti-Catholic views, there is little to no open conflict between the two churches. Additionally, Ioffe has placed Belarusians' atheism and the relatively-fast growth of Protestantism as diluting historical religious tensions.[13]

Konstanty Kalinowski and the January Uprising

[edit]

Belarusian nationalism began to emerge in the early 1860s, during the prelude to the January Uprising. The publishing of Mużyckaja prauda, the first newspaper written in the modern Belarusian language, began in 1861 under the leadership of Konstanty Kalinowski (Belarusian: Кастусь Каліноўскі, romanized: Kastuś Kalinoŭski). The newspaper advocated against the Russian Empire, called for the restoration of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Eastern Catholicism (which became unpopular after the large-scale return to the historical Belarusian faith of Eastern Orthodoxy), and spoke in support of land reform. In contrast, the West-Rusists, led by Mikhail Koyalovich (Kalinowski's primary political rival within Belarus), believed the Belarusians were a subset of the Russian nation, and advocated for the conversion of Catholics to Eastern Orthodoxy.[14]

When the January Uprising began, Kalinowski sought to foment rebellion in Belarus. According to his later writings, he aligned himself with Poland because, "the Polish cause is our cause, the cause of freedom."[a] A total of 260 battles were fought in the territory of what is now Belarus and Lithuania, according to Imperial Russian data. An estimated 67,957 people participated in the Uprising from Belarus and Lithuania, of whom at least one third were from the peasantry[15] (forming the Reds, the left wing of the Uprising),[16] in contrast to the Uprising's aristocratic leadership[15] (making up the Whites, the right wing).[16]

However, the January Uprising was swiftly crushed by the Russian Army. A total of 180 people were executed by Tsarist authorities for participation in the January Uprising, though the percentage of whom were peasants is disputed.[b] Just over a year after the Uprising's beginning, Kalinowski himself was hanged in Vilnius.[15] Kalinowski's Letters from Beneath the Gallows became a rallying cry for Belarusian nationalists, with its condemnation of the "Muscovites" and call to fight alongside Polish rebels.[16] A portion of one of the letters is included below:

There is no greater happiness on this earth, brothers, than if a man has intellect and learning. Only then will he manage to live in counsel and in plenty and only when he has prayed properly to God, will he deserve Heaven, for once he has enriched his intellect with learning, he will develop his affection and sincerely love all his kinsfolk. But just as day and night do not reign together, so also true learning does not go together with Muscovite slavery. As long as this lies over us, we shall have nothing. There will be no truth, no riches, no learning whatsoever. They will not drive us like cattle not to our well-being, but to our perdition.

This is why, my People, as soon as you learn that your brothers from near Warsaw are fighting for truth and freedom, don't you stay behind either, but, grabbing whatever you can – a scythe or an ax – go as an entire community to fight for your human and national rights, for your faith, for your native country. For I say to you from beneath the gallows, my People, that only then will you live happily, when no Muscovite remains over you.[17]

In spite of his later prestige, Kalinowski was a polarising figure at the time of his death, with Kalinowski's political opponent Jakub Gieysztor describing him as a "Lithuanian separatist." Józef Kajetan Janowski, on the other hand, a member of the Uprising's Polish National Government, called Kalinowski, "a true apostle of the Belarusian people." Kalinowski was also idolized by Polish rebels as a supporter of Polish nationalism. Regardless of differing views on his legacy, Kalinowski began to emerge as a Belarusian national hero during the 1930s, as Soviet educational institutions emphasized his role in history.[15] Following the defeat of the January Uprising, Belarusian nationalism faded from consciousness, amidst competition between Lithuanian, Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian nationalists.[17]

The Russian Revolution and Belarusian Democratic Republic

[edit]

Beginning in the 1890s, Belarusian nationalism began to re-emerge. Francišak Bahuševič's 1891 call for Belarusians to identify with their nation was followed by the foundation of Nasha Niva in Vilnius in 1909.[18] The Belarusian Socialist Assembly, a left-wing political party calling for the independence of Belarus, was founded in 1902.[19] Attempts were also made to restore the Uniate Church, with Metropolitan Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Andrey Sheptytsky making a secret visit to Belarus at the behest of nationalist leaders Ivan Luckievič and Anton Luckievich, though nothing developed from it. Belarusian nationalism found particular growth in northern and central Belarus, where religious plurality was more common than the Catholic West and Orthodox East.[20] However, nationalists faced the problems of apathy and hostility from their countrymen: With the majority of the intelligentsia becoming convinced of Belarusian nationalism only in the 1890s, few Belarusians, the majority of whom were peasants, had any unique Belarusian national consciousness, and primarily identified with Poland or Russia, depending on their religion.[18] Nationalists were also opposed by the local intellectuals of peasant and clerical origins; those who were not rooted in the old Polonized aristocracy or gentry. These intellectuals are referred to as West-Rusists or Westrussianists.[14][21][citation needed] One of the leading voices of the West-Rusists was historian and journalist Lukyan Solonevich, the father of anti-Soviet dissident and Tsarist philosopher Ivan Solonevich, as well as author Boris Solonevich.[21]

World War I initially brought little in terms of growth for Belarusian nationalism. However, following the February Revolution, public discussion began to take place on the future of the Belarusian nation. Left- and right-leaning groups, among them the Belarusian Socialist Assembly and the Belarusian Christian Democracy. Following the October Revolution, the First All-Belarusian Congress was held, bringing together representatives from throughout Belarus. At the Congress, it was agreed to pursue independence, but disagreements between the left and right wings emerged over when to declare independence. The right, informally referred to as radaŭcami[c] and consisting of delegates from the Belarusian Christian Democracy and Western Belorussia, sought immediate independence. On the other hand, the left, called the ablasnikami[d] and made up of delegates from the Belarusian Socialist Assembly and Eastern Belorussia, sought temporary confederation with Russia as a more realistic alternative within the context of World War I and widespread poverty in Belarus. At the Congress' conclusion, a compromise was reached. However, following the compromise, supporters of the Bolsheviks stormed the building, brawling with delegates.[22]

After the Bolshevik attack on the Congress was thwarted, it was reconvened. In response to the Bolsheviks, the Belarusian Democratic Republic was declared by a unanimous vote. At the time, the event received little recognition, with an adviser to the Imperial German Army on Belarusian affairs claiming that "the Belarusian secessionism, supported by a few Vilna archaeologists and journalists, ought to be considered a local matter of no political consequence."[23] Nonetheless, it marked a landmark in the development of Belarus as an independent nation; for the first time, Belarus had achieved independence, even if this was unrecognised.[22]

However, the first experiment in Belarusian independence was quickly thwarted by Soviet forces. Unable to establish itself and with its existence at the whims of its neighbors, the Belarusian Democratic Republic became collateral damage of the Polish–Soviet War. According to the Peace of Riga, the western portion of the country was annexed into the Second Polish Republic, and the eastern half became the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, which itself became a founding member of the Soviet Union in 1922.[24] Now, split between two nations, Belarusian nationalists followed two different strains of evolution, a process which continued until the country was reunited under Soviet rule in 1939.

Interwar period

[edit]In Poland

[edit]In Poland, Belarusian nationalism diverged along several lines, few of which outlived Poland's rule over the area. An early branch of Belarusian nationalism which emerged in the 1920s subscribed to Protestantism, rather than Greek Catholicism, as a unifying faith for Belarusians. The reasons for this choice were primarily economic; Protestant churches, which had begun missionary activity in Belarus that decade, had resources which Belarusian nationalist voices felt could be spent on the development of Belarus. The Protestant movement, on the other hand, saw local leaders as significant figures in assisting their missionary activity. As a result of Protestant missionary activity mixed with nationalism, the New Testament was translated into the Belarusian language by the British and Foreign Bible Society.[25]

Protestant Belarusian nationalists did not subscribe exclusively to any singular branch of Protestantism; some, like Branislaw Tarashkyevich, became followers of Methodism, while others became associated with Baptism. Additionally, others, such as Anton Luckievich, converted to Calvinism. The main representation of Protestant political power in Western Belorussia was the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, which, while officially having a platform of ambivalence towards religion, was led exclusively by Protestants. These same Protestant nationalists were tied to the Communist Party of Western Belorussia, with Belarusian Methodist leader Haliash Laukovich-Leuchyk saying, "I envision Evangelic socialism, or Communism, headed by Christ." The Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union collapsed in 1928 after its leadership was arrested by the Polish government due to concerns regarding their support for the Soviet Union.[25]

The Belarusian National Socialist Party, led by Fabijan Akinčyc, was founded in 1933, and became an additional force of Belarusian nationalism. Subscribing to Nazism, the Belarusian National Socialist Party viewed both Polonization and Russification as threats to the Belarusian nation, and placed emphasis on antisemitism, blaming Jews for Belarusian economic misfortunes. Akinčyc, having ties to the Foreign Office of the Nazi Party, received attention from the Polish government, and a ban on the party's activities in the Wilno Voivodeship. This ban, as well as additional bans in the Polesie, Białystok, and Nowogródek Voivodeships, led to the marginalisation of the party[26] and Akinčyc leaving Poland for Berlin in the spring of 1939, where he faded into irrelevance.[27]

In the Soviet Union

[edit]Belarusian nationalism received state sponsorship as part of the Soviet Union's indigenization policies.[28] Unlike in Poland, where Belarusian nationalism developed in several various competing strains, Belarusian nationalism in the Soviet Union primarily developed along broadly similar lines as their 19th-century ancestors - pro-western versus pro-Russian. The pro-western strain of Belarusian intellectuals initially dominated the leadership of the Byelorussian SSR, and received a boost from the emigration of twelve members of the intelligentsia from Polish Belarus. However, with the promotion of more Belarusian peasants to the SSR's leading positions, the pro-western faction was marginalized before being eventually destroyed altogether during the Great Purge of the mid-1930s.[23]

There were additionally uprisings against Soviet control of Belarus, such as the Slutsk uprising, but they were unsuccessful.

World War II

[edit]World War II was a significant event in Belarusian history, and led to seismic shifts in Belarusian culture and politics. Belarusian nationalism entered the war without much consideration for its status by German forces. Only after the assassination of Wilhelm Kube in 1943, two years after Belarus was initially occupied by Nazi Germany, were attempts made to grant the Belarusians any visible autonomy. The Belarusian Central Council, under the leadership of Radasłaŭ Astroŭski, was established and permitted to use Belarusian national symbols, such as the white-red-white flag of the Belarusian Democratic Republic.[29]

On 27 June 1944, shortly following the recapture of Minsk by the Red Army, the Second All-Belarusian Congress was held in Minsk's Opera House. Antisemitism was additionally espoused by the Second All-Belarusian Congress, with speaker Yaukhim Kipel claiming that any assembly of Belarusians convened by the Soviet government had been at least 40% Jewish, and therefore not representative of the Belarusian people. Shortly afterwards, the collaborationist forces fled west with retreating German forces. Some later fled to the United States.[29] Collaborationist forces of Belarusian nationalists were also utilised by the Germans as part of an effort to foment insurgency in Soviet Belarus, with little success. Michał Vituška and Usievalad Rodzka were among those who were part of these efforts.

However, Belarusian nationalism was not exclusive to collaborators. Belarusian nationalism was supported by certain participants in the struggle of the Allies, among them Vincent Žuk-Hryškievič (later President of the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic) and Alexander Nadson (a Belarusian Greek Catholic priest), both of whom were members of Anders' Army. On the Soviet side, future Belarusian nationalists also participated in the Belarusian partisan movement, among them Ales Adamovich.

Belarusian collaborationists remain a controversial topic in Belarus, being used by President Alexander Lukashenko as justification for banning the white-red-white flag and other symbols used by the Belarusian opposition. Contrary to claims by the Belarusian government, however, the Belarusian partisans have, for the most part, formed the basis of Belarusian nationalism, being evoked by both the government and opposition.[30] Despite this, however, some right-wing organisations within the opposition have sought to rehabilitate the image of collaborators, among them the Young Front.[31]

Post-war

[edit]Following the war, the pro-western sect of Belarusian nationalism again faded from public discussion. At this time, however, the opposing pro-Russian sect of Belarusian nationalists saw the groundwork being laid for its modern existence. The flag of Belarus was adopted in 1951,[32] and memorialisation of Soviet partisans became an extensive part of the Belarusian government, which was led almost entirely by former partisans until the late 1970s.[33] Pyotr Masherov, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia from 1964 to 1980, placed significant focus on recognition of the partisan movement, including construction of monuments to the Khatyn massacre and the partisan movement.[34] In a 2002 survey by Grigory Ioffe, 23% of Belarusians named Masherov as a prominent Belarusian. By comparison, 20% of Belarusians named Kalinowski as a prominent Belarusian. Most symbols of the pro-Russian Belarusian nationalists (also including the band Pesniary) began in this time period.[33]

The road to independence (1988–1991)

[edit]

Eight years after Masherov's sudden death in 1980, the Belarusian nationalist movement began to re-emerge, this time under the leadership of young historian Zianon Pazniak. Pazniak's 1988 discovery of the Kurapaty mass grave site brought widespread backlash against the Soviet government. At the time, the Soviet government unsuccessfully attempted to paint Kurapaty as a Nazi, rather than Soviet, mass grave site. Around the same time, the pro-western and pro-Russian factions of the nationalist movement began to conflict openly.[29] The Belarusian Popular Front was established in 1989 under Pazniak's leadership, and 37 of its members were elected a year later, in the 1990 Belarusian Supreme Soviet election.[35]

The first major protest action of Belarusian nationalists was the 1991 Belarusian strikes. Beginning as a movement against tax increases by the 1991 Soviet monetary reform, the strikes quickly drew support from the Belarusian Popular Front, and became a more wide-reaching protest against Soviet control of Belarus and in favour of greater autonomy for the Byelorussian SSR. Though the strikes' more nationally minded demands were rejected by the Soviet government, Belarus became independent only a few months later, in the aftermath of the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt.[36]

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union

[edit]

Following Belarusian independence, the pro-western nationalist clique, led by Pazniak and Stanislav Shushkevich, a Catholic ex-Communist functionary, once again took control of the country. Attempts were made to restore the Belarusian language, which had been substantially diminished by Russification under Masherov's rule; a 1990 law established Belarusian as the sole official language, and by 1995, 70-80% of schools taught in the Belarusian language.[37] Pazniak also unsuccessfully urged the government to attack pro-Russian ways of thinking.[10]

The 1994 Belarusian presidential election marked a significant conflict between pro-Russian and pro-Western groups of nationalists. In the former camp was Alexander Lukashenko, a collective farm manager from the country's east. In the latter camp were Pazniak and Shushkevich.[37] Lukashenko won the election and soon set out reversing the trends of Belarusianisation which had been carried out by the government from 1991 to 1994. In 1995, Lukashenko held a referendum to establish Russian as a co-official language with Belarusian and restore the symbols of the Byelorussian SSR. The referendum succeeded with 64.8% turnout, though the results were widely condemned as rigged by the opposition and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. For his part, Lukashenko claimed that he was not involved in Russification, instead blaming Masherov.[37]

Early anti-Lukashenko activities (1994–1999)

[edit]Protests against Lukashenko by pro-western Belarusian nationalists began soon after his election, and intensified following the 1995 referendum. In the face of Lukashenko pivoting from nationalism to supporting the annexation of Belarus by Russia, protests began in Minsk. Known as the Minsk Spring, the protests, including the Belarusian Popular Front and the Ukrainian National Assembly – Ukrainian People's Self-Defence from Ukraine. The protests were suppressed, leading to Pazniak fleeing to Poland, and the process of integration with Russia continued until the 1999 Freedom March. As a result of the Freedom March, the Union State failed to lead to the actual integration of Russia and Belarus.[38]

2000–2022

[edit]Following the success of the Freedom March, the Belarusian nationalist movement diminished. Subsequent protests were held the next year with the approval of the government. Organisations such as the Young Front continued to exist, but failed to take control of the country. Over the course of time, Lukashenko gradually pivoted away from Russia, including the 2009 Milk War, a diplomatic conflict regarding Russian attempts to privatise Belarus's dairy industry.[39]

In September 2019, Lukashenko claimed that Polish city Białystok are Belarusian lands and justified the Soviet invasion of Poland as "defense" of Western Belorussia from Nazis.[40]

During the 2020 Belarusian presidential election, Lukashenko accused the Russian government of attempting to destabilise the country, and claimed the opposition received support from Wagner Group mercenaries in an attempted terrorist attack.[41] Members of the opposition conversely accused Lukashenko of selling the country out to foreign actors, with Ales Bialiatski referring to the former's government as a "regime of occupation" prior to his 2021 arrest.[42] Russia further enabled a government crackdown on the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests, with Russian President Vladimir Putin saying that Russia's military was prepared to militarily intervene if it felt necessary.[43]

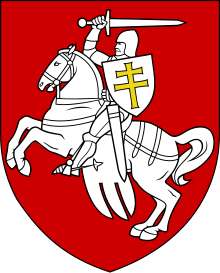

In response to the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests, the official Belarusian authorities considered to equate the white-red-white flag and slogan "Long Live Belarus!" with Nazi symbolism.[44] However, the Belarusians expressed their disagreement to the House of Representatives of the National Assembly of the Republic of Belarus that the white-red-white flag is extremist.[45] In November 2022, the official Belarusian authorities included slogan "Long Live Belarus!" (and response to it "Long live!") into the list of Nazi symbolism, despite its much earlier usage than the Adolf Hitler's rise to power and establishment of the Nazi Party (the slogan "Long Live Belarus!" was first used in 1905–1907 by a Belarusian poet Yanka Kupala).[46][47] Furthermore, there were cases in 2022 when people in Belarus were arrested or even sentenced to multiple years in prison for the usage of Pahonia symbol when they publicly painted it or left a sticker featuring it.[47][48] Íhar Marzaliúk, a pro-Lukashenko politician and historian, in his speeches deemed the white-red-white flag and modern symbolism of Pahonia as extremist/Nazi.[49][50]

Since 2022

[edit]

Since the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which was partially launched from the territory of Belarus, fears that Russia could potentially annex Belarus have increased.[51] Lukashenko has broadly supported Russia diplomatically, but has refused to directly involve the Belarusian military in combat. The Kyiv Independent, a Ukrainian media outlet, has referred to Lukashenko's Belarus in 2022 as being, "barely independent from the Kremlin," noting Belarusian economic and military dependence on Russia, efforts to suppress usage of the Belarusian language, and Russia's military presence in Belarus.[52]

Belarusian nationalists in Ukraine

[edit]In light of Lukashenko's increasing authoritarianism, several Belarusian nationalists have fled south to Ukraine. Prior to the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, Mykhailo Zhyznevskyi, who had fled Belarus to Ukraine and joined the Ukrainian National Assembly – Ukrainian People's Self-Defence, was killed during Euromaidan. Following the outbreak of the war, Belarusian nationalists have formed military units supporting Ukraine. Among the most notable of these is the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment, formed following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which additionally fights for the independence of Belarus from Russia.[53]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Belarusian: Польскае дзела гэта наша дзела, гэта вольнасці дзела., romanized: Polskaje dziela heta naša dziela, heta volnasci dziela

- ^ Estimates from the Belarusian Ministry of Education place the number at 22.93%, while historian Susanna Sambuk claims a percentage of 18%.

- ^ Belarusian: Радаўцамі, lit. 'Soldiers'

- ^ Belarusian: Абласнікамі, lit. 'Regionalists'

Further reading

[edit]- Kasmach, Lizaveta (2023). Belarusian Nation-Building in Times of War and Revolution: Nation-Building in Times of War and Revolution. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-386-634-4.

References

[edit]- ^ Walker, Shaun (22 August 2020). "How the two flags of Belarus became symbols of confrontation". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ "Tomas Baranauskas: Litvinistams svarbiausia turėti gražią istoriją, kuri galėtų sutelkti tautą" [Tomas Baranauskas: For Litvinists, the important thing is to have a beautiful story to rally the nation]. bernardinai.lt (in Lithuanian). 29 September 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Bury, Jan (24 July 2008). "Litwinizm - nowe zjawisko na białorusi" [Litvinism - a new phenomenon in Belarus]. Kresy.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Opinion: Why are our neighbours poaching our history?". Lithuania Tribune. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Gurevičius, Ainis. "Karininkas: jie kels ginklą prieš Lietuvą nuoširdžiai tikėdami, kad Vilnius priklauso jiems". Alfa.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Марзалюк, Ігар (18 March 2023). "Марзалюк: Вільня можа быць за межамі Беларусі, але заўсёды мусіць заставацца ў нашым сэрцы". Belarus-news.by (in Belarusian). Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Grigaliūnaitė, Violeta. "Istorijos profesorius baltarusiškos televizijos BELSAT laidoje apie Vilnių: jį įkūrė baltarusiai". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Арлоў, Уладзімер (7 October 2010). "Ці належала Вільня БССР?". Радыё Свабода (in Belarusian). Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Pazniak, Zianon (25 March 2023). "ПАЗНЯК: як беларусы стварылі краіну, Вільня – наша, Дзень Волі – галоўнае свята, БНР – 105 год (related timelapse: from 48:10 to 01:11:32)". YouTube.com (in Belarusian). Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ a b Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1261–1262. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ "For the Sake of a Brighter Future, Belarusians Argue about the Past". PONARS Eurasia. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1246–1248. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1242–1243. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ a b "History Of Belarus In The Russian Empire - About History". 7 December 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hierasimčyk, Vasil (22 December 2018). "Гісторык папунктава разабраў артыкул Мінадукацыі пра Каліноўскага: «Старанная фальсіфікацыя, якая разбіваецца «Лістамі з-пад шыбеніцы»" [Historian analyses MinEd article about Kalinouski, point by point: "Elaborate falsification, broken by Letters from the Gallows"]. Nasha Niva (in Belarusian). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Kastus Kalinouski (1838-1864)". Virtual Guide to Belarus. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b Parfenov, Denis. "Rise and Fall of Belarusian National Identity" (PDF). prfnv.keybase.pub. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1247. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ Marples, David R. (1999). Belarus: A Denationalized Nation. Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9057023431.

- ^ Łatyszonek, Oleg; Słomczynska, Jerzyna (Fall 2001). "Belarusian Nationalism and the Clash of Civilizations". International Journal of Sociology. 31 (3): 65. doi:10.1080/15579336.2001.11770233. JSTOR 20628624. S2CID 141000668.

- ^ a b Aliaksandr Bystryk: Russianist Agitation Against Belarusian Nationalism During WWI, 9 March 2021, retrieved 29 December 2023

- ^ a b Kasiak, Kanstancin (6 January 2015). "Пачатак беларускай дзяржаўнасці" [The Beginnings of Belarusian Statehood]. Budzma Bielarusami! (in Belarusian). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1255. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^

Treaty of Peace between Poland, Russia and the Ukraine on Wikisource. Accessed 22 January 2023

Treaty of Peace between Poland, Russia and the Ukraine on Wikisource. Accessed 22 January 2023

- ^ a b Łatyszonek, Oleg; Słomczynska, Jerzyna (Fall 2001). "Belarusian Nationalism and the Clash of Civilizations". International Journal of Sociology. 31 (3): 65–68. doi:10.1080/15579336.2001.11770233. JSTOR 20628624. S2CID 141000668.

- ^ Hlahoŭskaja, Liena (9 July 2006). "Беларускі нацыянал-сацыялізм і асяродзьдзе "Новага шляху" (кБНІ)" [Belarusian national socialism and the environment of New Way (kBNI)]. Belarus - Our Land (in Belarusian). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Turonak, Jury. "Фабіян Акінчыц — правадыр беларускіх нацыянал–сацыялістаў" [Fabijan Akinčyc - leader of the Belarusian national socialists]. Belarusian Historical Review (in Belarusian). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Bekus, Nelly (2010). Struggle over Identity : the official and the alternative "Belarusianness". Budapest: CEU Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-5814-2. OCLC 649837711.

- ^ a b c Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1255–1256. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (8 November 2020). "'Crush the fascist vermin': Belarus opposition summons wartime spirit". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Малады Фронт тлумачыць, каго лічыць героямі" [Young Front explains who it considers heroes]. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Belarusian). 28 March 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Флаги БССР 1920-1990" [Flags of the BSSR 1920-1990]. vexillographia.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ a b Ioffe, Grigory (December 2003). "Understanding Belarus: Belarusian Identity". Europe-Asia Studies. 55 (8): 1259. doi:10.1080/0966813032000141105. JSTOR 3594506. S2CID 143667635.

- ^ Ioffe, Emmanuel (2008). From Myasnikov to Malofeyev: the Rulers of the BSSR. Minsk. pp. 140–141.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Гісторыя Партыі БНФ" [History of the BPF Party]. Belarusian Popular Front (in Belarusian). 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Navumchyk, Siarhei (21 May 2022). "Чаму рабочыя асьвісталі Шушкевіча?" [Why did workers shout down Shushkevich?]. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Belarusian). Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "Стагодзьдзе Машэрава: народны герой ці выканаўца волі Крамля" [Masherov's century: People's hero or executor of the Kremlin's will?]. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Belarusian). 10 February 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Кроў і таямніцы Маршу Свабоды '99 – архіўнае відэа" [Blood and Secrets of the '99 Freedom March – archive video]. Nasha Niva (in Belarusian). 23 June 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ "Has Moscow Had Enough Of Belarus's Lukashenka?". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "A. Lukašenka: Balstogė ir Vilnius yra Baltarusijos miestai". Lrytas.lt (in Lithuanian). 19 September 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Bykowski, Pavluk; Bushuev, Mikhail (31 July 2020). "Belarus accuses Russians, critics of plotting attack". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski: Nobel Prize-winning activist stands trial in Belarus". BBC. 5 January 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, Becky (11 March 2022). "Why Belarus is so involved in Russia's invasion of Ukraine". NPR. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "White-red-white flag and slogan "Long Live Belarus" to be equated with Nazi symbols". Voices of Belarus.

- ^ "Persecution for Use of Symbols. Belarus, 2021". Penbelarus.org. 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Belarus Adds Historic Slogan Used By Opposition To Outlawed Nazi-Symbols List". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ a b Romanenko, Valentina. "Lukashenko regime deems "Long live Belarus!" to be Nazi slogan". Ukrainska Pravda.

- ^ "2022 Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Belarus". U.S. Embassy in Belarus. 25 May 2023.

- ^ Гурневіч, Дзьмітры (21 November 2022). "Дэпутат Марзалюк 13 хвілінаў бараніў на СТВ «Пагоню». Але ёсьць нюанс". Радио Свобода (in Belarusian).

- ^ "Марзалюк паказаў «сведчанне злачынстваў пад бела-чырвона-белым сцягам». Але гэта хлусня — вось што на фота". Nasha Niva (in Belarusian). 10 July 2023.

- ^ Timtchenko, Ilya (1 September 2022). "Might Putin Annex Belarus?". CEPA. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Yeryoma, Maria (4 January 2023). "With the world looking away, Russia quietly took control over Belarus". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Telegram Trap: Minsk Snares Belarusians Seeking To Fight For Ukraine". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 19 March 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2023.