Trung sisters' rebellion

| Trung sisters' rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the southward expansion of the Han dynasty | |||||||

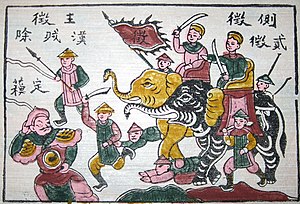

The Trung sisters' rebellion depicted in a Đông Hồ folk painting titled "Trưng Vuơng trừ giặc Hán" (徴王除賊漢 - Trung Queens eliminating the Han enemies). Trưng Trắc (徴側) sits on white elephant and Trưng Nhị (徴貳) on black elephant, accompanied by weapon-toting Lạc Việt soldiers; Han soldiers are felled and dead; Han governor Su Ding (蘇定) looks back while fleeing. All wear anachronistic clothing. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Han dynasty | Lac Viet | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Su Ding (Governor) Ma Yuan[a] Liu Long |

Trưng Trắc Trưng Nhị Đô Dương Chu Bá | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

20,000 soldiers 2,000 tower-ships[1] | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 40–50% of Han soldiers (mostly from epidemic)[3] |

Trưng sisters' forces: • several tens to hundreds killed; • over 20,000 surrendered[4][5] Đô Dương's forces: • over 5,000 (both killed and surrendered);[4] • over 300 exiled[6] Chu Bá's forces: • several tens to hundreds executed[2] | ||||||

| History of Vietnam |

|---|

|

|

|

The Trưng sisters' rebellion was an armed civil uprising in the southern provinces (today Northern Vietnam) of Han China between 40 CE and 43 CE. In 40 CE, the Luoyue leader Trưng Trắc and her sister Trưng Nhị rebelled against Chinese authorities in Jiaozhi (in what is now northern Vietnam). In 42 CE, Han China dispatched General Ma Yuan to lead an army to strike down the Luoyue rebellion of the Trưng sisters. In 43 CE, the Han army fully suppressed the uprising and regained complete control. The Trưng sisters were captured and beheaded by the Han forces,[7][8] although Vietnamese chronicles of the defeat records that the two sisters, having lost to Han forces, decided to commit suicide by jumping down the Hát Giang river, so as not to surrender to the Han.[9][10][11]

Background

[edit]

One prominent group of ancient people in Northern Vietnam (Jiaozhi, Tonkin, Red River Delta region) during the Han dynasty's rule over Vietnam was called the Lac Viet or the Luòyuè in Chinese annals.[12] The Luoyue were considered a Baiyue-related group in the region, and it is hard to say whether Luoyue were a tribal confederation or a collective designation for various unaffiliated Yue tribes who inhabited in North Vietnam. They practiced non-Chinese tribal ways, matrilineality, facial tattooing, and slash-and-burn agriculture.[13][14] According to French sinologist Georges Maspero, some Chinese immigrants arrived and settled along the Red River during the usurpation of Wang Mang (9–25 CE) and the early Eastern Han, while two Han governors of Jiaozhi Xi Guang (?-30 CE) and Ren Yan, with support from Chinese scholar-immigrants, conducted the first "sinicization" on the local tribes by introducing Chinese-style marriage, opening the first Chinese schools, and introducing Chinese philosophies, therefore provoking cultural conflict.[15] American philologist Stephen O'Harrow indicates that the introduction of Chinese-style marriage customs might have come in the interest of transferring land rights to Chinese immigrants in the area, replacing the matrilineal tradition of the area.[16]

The Trưng sisters were daughters of a wealthy aristocratic family of Lac ethnicity.[17] Their father had been a Lac lord in Mê Linh district (modern-day Mê Linh District, Hanoi). Trưng Trắc (Zheng Ce)'s husband was Thi Sách (Shi Suo), was also the Lac lord of Chu Diên (modern-day Khoái Châu District, Hưng Yên Province).[18] Su Ding (governor of Jiaozhi 37–40 CE), the Chinese governor of Jiaozhi province at the time, is remembered by his cruelty and tyranny.[19] According to Hou Hanshu, Thi Sách was "of a fierce temperament".[20] Trưng Trắc, who was likewise described as "possessing mettle and courage",[21] fearlessly stirred her husband to action. As a result, Su Ding attempted to restrain Thi Sách with laws, literally beheading him without trial.[22] Trưng Trắc became the central figure in mobilizing the Lac lords against the Chinese.[23]

Revolt

[edit]In March[7] of 40 CE, Trưng Trắc and her younger sister Trưng Nhị (Zheng Er), led the Lac Viet people to rise up in rebellion against the Han.[7][8][24] The Hou Han Shu recorded that Trưng Trắc launched the rebellion to avenge the killing of her dissident husband.[18][verification needed] Other sources indicate that Trưng Trắc's movement towards rebellion was influenced by the loss of land intended for her inheritance due to the replacement of traditional matrilineal customs.[16] It began at the Red River Delta, but soon spread to other Lac tribes and non-Han people from an area stretching from Hepu to Rinan.[17] Chinese settlements were overrun, and Su Ting fled.[23] The uprising gained the control of about sixty-five towns and settlements.[8] Trưng Trắc was proclaimed as the queen.[7] Even though she gained control over the countryside, she was not able to capture major fortified towns.[7]

Han counterattack

[edit]

The Han government (situated in Luoyang) responded rather slowly to the emerging situation.[7] In May or June of 41 CE, Emperor Guangwu gave the orders to initiate a military campaign. The strategic importance of Jiaozhi is underscored by the fact that the Han sent their most trusted generals, Ma Yuan and Duan Zhi to suppress the rebellion.[25] Ma Yuan was given the title Fubo Jiangjun (伏波將軍; General who Calms the Waves).[7] He would later go down in Chinese history as a great official who brought Han civilization to the barbarians.[25]

Ma Yuan and his staff began mobilizing a Han army in southern China.[7] It consisted 20,000 regulars and 12,000 regional auxiliaries.[8][26] From Guangdong, Ma Yuan dispatched a fleet of supply ships along the coast.[7]

In the spring of 42 CE, the imperial army reached high ground at Lãng Bạc, in the Tiên Du mountains of what is now Bắc Ninh. Yuan's forces battled the Trưng sisters, beheaded several thousand of Trưng Trắc's partisans, while more than ten thousand surrendered to him.[27] The Chinese general pushed on to victory. During the campaign he explained in a letter to his nephews how “greatly” he detested groundless criticism of proper authority. Yuan pursued Trưng Trắc and her retainers to Jinxi Tản Viên, where her ancestral estates were located; and defeated them several times. Increasingly isolated and cut off from supplies, the two women were unable to sustain their last stand and the Chinese captured both sisters in early 43 CE.[28] Trưng Trắc's husband, Thi Sách, first escaped to Mê Linh, then onward to a place called Jinxijiu and was not captured until three years later.[27] The rebellion was brought under control by April or May 43 CE.[7] Ma Yuan had Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị decapitated,[7][8] and sent their heads to the Han court at Luoyang.[27] By the end of 43 CE, the Han army had taken full control over the region by defeating the last pockets of resistance.[7] Yuan reported his victories, and added: “Since I came to Jiaozhi, the current troop has been the most magnificent."[27]

Aftermath

[edit]

In their reconquest of Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen, Han forces also appear to have massacred most of the Lạc Việt aristocracy, beheading five to ten thousand people and deporting several hundred families to China.[29] After the Trưng sisters were dead, Ma Yuan spent most of the year 43 building up Han administration in the Red River Delta and preparing the local society for direct Han rule.[30] General Ma Yuan aggressively sinicized the culture and customs of the local people, removing their tribal ways, so they could be more easily governed by Han China. He melted down the Lac bronze drums, their chieftains' symbol of authority, to cast a statue of a horse, which he presented to Emperor Guangwu when he returned to Luoyang in the autumn of 44 AD.[7] In Ma Yuan's letter to his nephews while campaigning in Jiaozhi, he quoted a Chinese saying: "If you do not succeed in sculpting a swan, the result will still look like a duck."[29] Ma Yuan then divided the Tây Vu (Xiyu, modern day Phú Thọ province) County into Fengxi County and Wanghai County, seized the last domain of the last Lạc monarch of Cổ Loa.[31] Later, Chinese historians writing of Ma Yuan's expedition referred to the Luo/Lạc as the "Luoyue" or simply as the "Yue".[32] "Yue" had become a category of Chinese perception designating myriad groups of non-Chinese peoples in the south. The Chinese considered the Lac to be a "Yue" people, and it was customary to attribute certain cliched cultural traits to the Lạc in order to identify them as "Yue".[33][34]

Demise of the Dong Son culture and the rise of Li-Lao culture

[edit]

The Trung sisters' defeat in 43 CE also subsequently coincided with the end of Dong Son culture and Dong Son metallurgical drum tradition that had been flourished in Northern Vietnam for centuries,[35] as the Han tightened their grip over the region, culminating in process that transformed the non-Sinic people.[36] Local Red River Delta elites pledged themselves to Chinese cultural norms and Chinese hierarchy. Chinese techniques, religions, and taxation were forced upon or voluntarily embraced by indigenous tribes. The regions' demographics and history shifted.[36] Jiaozhou or the Red River Delta gradually became semi-integrated into Chinese empires through Han to Jin dynasty. No large-scale uprising occurred in the region for roughly 400 years.[37] The successful reconquest of Northern Vietnam also gave the Han dynasty secured gateways to access southern maritime trade routes and establish ties with various polities in Southeast Asia and beyond, and increasing relationships between China and the Indian Ocean world.[38] The Han records mention a distant Daqin (whether Rome or not) embassy came from the South and entered the Han empire through Rinan (Central Vietnam) in 166 CE.[39] Along with trade and knowledge, religions such as Buddhism possibly spread to China via Northern Vietnam from southern sea, along with obvious inland Silk Road, during the second and third centuries.[40]

The decline of Dong Son culture in the Red River Delta led to the rise of the Li Lao drum culture (200–750 CE) in the mountainous areas between the Pearl and the Red River, or the People between the Two Rivers, stretching from present-day Guangdong, Guangxi, to Northern Vietnam.[41] The culture was known for casting large Heger type II drums that share many similarities with Dong Son's Heger type I drums. Lǐ (俚) and Lǎo (獠) are interchangeably perceived as non-Chinese and contemporary sources did not prefer a specific ethnicity for them, the culture could have been multiethnic as modern Vietnam and Southern China are, made up by primary Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic speaking tribes,[42][43] but some probably were ancestors of modern-day Li people in Hainan.[44] After the collapse of the Han dynasty in the early third century CE and China being in a state of turmoil for approximately 400 years, no Chinese dynasty was strong enough to exert its control and influence over this region until the powerful Tang dynasty. Meanwhile numerous independent Dong chiefdoms representing the Li Lao drum culture's autonomy created the voidness of imperial authorities in the regions that were inside the empire.[45] According to researcher Catherine Churchman in her 2016 book The People Between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of a Bronze Drum Culture, 200–750 CE, due to Li-Lao culture's massive dominantly influences, instead of becoming more assimilated into China, the Red River Delta from 200 to 750 CE experienced a reverse effect on sinicization or "de-Sinifying effect", therefore the history of sinicization of the region should be reconsidered.[46]

Perception

[edit]

The Trưng sisters' rebellion marked a brilliant epoch for women in ancient southern China and reflected the importance of women in early Vietnamese society.[28] One reason listed by medieval Confucian scholars for the defeat is the desertion by rebels because they did not believe they could win under a woman's leadership.[47] The fact that women were in charge was blamed as a reason for the defeat by historical Vietnamese texts written during the medieval era when Vietnamese society had become a Confucian patriarchy. Modern Vietnamese historians and social activists however retroactively ridiculed and mocked men for doing nothing while "mere girls", whom they viewed with revulsion, took up the banner of revolt. The Vietnamese poem which talks about the revolt of the Trung Sisters while the men did nothing was not intended to praise women nor view war as women's work as it has been wrongly interpreted.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

The Vietnamese proverb Giặc đến nhà, đàn bà cũng đánh ("when the enemy is at the gate, even the women go out fighting") has been recited as evidence of Lạc women's respected status.[54] In the contrary, other interpretations of the quote state that it only means fighting in war is inappropriate for women and its only when the situation is so desperate that the war has spread to their home then women should enter the war.[55][56][57]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tower-ship General Duan Zhi, was also dispatched but died of illness before Han forces engaged Trưng sisters' forces; Ma Yuan took command of Duan Zhi's troops[1]

- ^ Jiaozhou Waiyu Ji claims that Trưng Trắc's husband also participated in the rebellion, while HHS mentions nothing about his whereabouts or activities during or after the rebellion. ĐVSKTT claims that he had been executed by Han grand-administrator Su Ding before the rebellion.

Citation

[edit]- ^ a b Hou Hanshuvol. 24 "Account of Ma Yuan"

- ^ a b Jiaozhou Waiyu Ji, as quoted in Li Daoyuan's Shuijing zhu vol. 37

- ^ Hou Hanshu, vol. 24 "Account of Ma Yuan" quote: "軍吏經瘴疫死者十四五。"

- ^ a b Hou Hanshu, vol. 24 "Account of Ma Yuan"

- ^ Hou Hanshu, vol. 22 "Account of Liu Long"

- ^ Hou Hanshu, Vol. 86 "Account of the Southern Barbarians"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bielestein (1986), p. 271.

- ^ a b c d e Yü (1986), p. 454.

- ^ "Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (Complete History of Dai Viet)" (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-16.

- ^ "Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (Complete History of Dai Viet)" (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2024-02-16.

- ^ Book 3: kỷ thuộc Tây Hán, kỷ Trưng Nữ Vương, kỷ thuộc Đông Hán, kỷ Sĩ Vương, book of History of Greater Vietnam (Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư)

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 28.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 63–64.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b O'Harrow, Stephen (1979). "From Co-loa to the Trung Sisters' Revolt: VIET-NAM AS THE CHINESE FOUND IT". Asian Perspectives. 22 (2): 159–61. JSTOR 42928006 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Brindley (2015), p. 235.

- ^ a b Lai (2015), p. 253.

- ^ Scott (1918), p. 312.

- ^ Hou Hanshu, Vol. 86. text: "甚雄勇"

- ^ Jiaozhou Waiyu Ji, as quoted in Li Daoyuan's Shuijing zhu vol. 37. text: "側爲人有膽勇"

- ^ Scott (1918), p. 313.

- ^ a b Taylor (1983), p. 38.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 78.

- ^ a b Brindley (2015), p. 236.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Kiernan (2019), p. 80.

- ^ a b Lai (2015), p. 254.

- ^ a b Kiernan (2019), p. 81.

- ^ Taylor (1983), p. 45.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 82.

- ^ Taylor (1983), p. 33.

- ^ Taylor (1983), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Brindley (2015), p. 31.

- ^ Korolkov 2021, p. 187.

- ^ a b Kiernan (2019), p. 84.

- ^ Churchman 2016, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 85.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 86.

- ^ Kiernan (2019), p. 92.

- ^ Korolkov 2021, p. 8.

- ^ Churchman 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Korolkov 2021, p. 192.

- ^ Churchman 2016, p. 9.

- ^ Churchman 2016, pp. 107, 113.

- ^ Churchman 2016, p. 204.

- ^ Taylor (1983), p. 41.

- ^ McKay et al. (2012), p. 134.

- ^ Gilbert, Marc Jason (2007). "When Heroism is Not Enough: Three Women Warriors of Vietnam, Their Historians and World History". World History Connected. 4 (3).

- ^ Taylor (1983), p. 334.

- ^ Dutton, Werner & Whitmore (2012), p. 80.

- ^ Hood (2019), p. 7.

- ^ Crossroads. Northern Illinois University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies. 1995. p. 35. "TRUNG SISTERS © Chi D. Nguyen". viettouch.com. Retrieved 17 June 2016. "State and Empire in Eurasia/North Africa" (PDF). Fortthomas.kyschools.us. Retrieved 2016-06-17. "Ways of the World" (PDF). Cartershistories.com. Retrieved 2016-06-17. "Strayer textbook ch03". slideshare.net. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2016. "Bà Trưng quê ở châu Phong - web". viethoc.com. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Nguyˆen, Van Ky. "Rethinking the Status of Vietnamese Women in Folklore and Oral History" (PDF). University of Michigan Press. pp. 87–107 (21 pages as PDF file).

- ^ Tai (2001), p. 1.

- ^ Tai (2001), p. 48.

- ^ Tai (2001), p. 159.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bielestein, Hans (1986), "Wang Mang, the restoration of the Han dynasty, and Later Han", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 223–290

- Brindley, Erica (2015). Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, C.400 BCE-50 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10708-478-0.

- Churchman, Catherine (2016). The People Between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of a Bronze Drum Culture, 200–750 CE. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-442-25861-7.

- Dutton, George Edson; Werner, Jayne Susan; Whitmore, John K. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press.

- Gilbert, Marc Jason (2007). "When Heroism is Not Enough: Three Women Warriors of Vietnam, Their Historians and World History". World History Connected. 4 (3).

- Hood, Steven J. (2019). Dragons Entangled: Indochina and the China-Vietnam War. Taylor & Francis.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press.

- Korolkov, Maxim (2021). The Imperial Network in Ancient China: The Foundation of Sinitic Empire in Southern East Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-00047-483-1.

- Lai, Mingchiu (2015), "The Zheng sisters", in Lee, Lily Xiao Hong; Stefanowska, A. D.; Wiles, Sue (eds.), Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. - 618 C.E, Taylor & Francis, pp. 253–254, ISBN 978-1-317-47591-0

- Li, Tana (2011), "Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ) in the Han Period Tongking Gulf", in Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 39–53, ISBN 978-0-812-20502-2

- McKay, John P.; Hill, Bennett D.; Buckler, John; Crowston, Clare Haru; Hanks, Merry E. Wiesner; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Beck, Roger B. (2012). Understanding World Societies, Combined Volume: A Brief History. Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-1-4576-2268-7.

- Scott, James George (1918). The Mythology of all Races: Indo-Chinese Mythology. University of Michigan.

- Tai, Hue-Tam Ho (2001). The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22267-0.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986), "Han foreign relations", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–463