Tin Can Cathedral

49°54′44.12″N 97°08′2.93″W / 49.9122556°N 97.1341472°W

The Tin Can Cathedral (Ukrainian: Бляшана Катедра, romanized: Blyashana Katedra) was the first independent Ukrainian church in North America. It was the heart of the Seraphimite Church. Founded in Winnipeg, it had no affiliation with any church in Europe.

Ukrainian immigrants began arriving in Canada in 1891 mainly from the Austro-Hungarian provinces, the regions of Bukovina and Galicia. The new arrivals from Bukovina were Eastern Orthodox, those from Galicia Eastern Catholic. In either case it was the Byzantine Rite with which they were familiar. By 1903 the Ukrainian immigrant population in Western Canada had become large enough to attract the attention of religious leaders, politicians, and educationalists.

Principals

[edit]

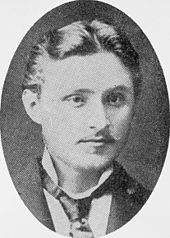

The central character in the Ukrainian community in Winnipeg at the time was Cyril Genik (1857–1925). He came from Galicia, having graduated from the Ukrainian Academic Gymnasium in Lviv and studied law briefly at the University of Chernivtsi.[1] Genik was a friend of Ivan Franko, the Ukrainian author of "Лис Микита" (Fox Mykyta)[2] who was nominated for the Nobel Prize In Literature. Franko's biting satire on the Western Ukrainian clergy of his day and his socialist leanings were probably shared by Genik who happened to be best man at the author's wedding. Freeing the populace of the clergy, along with land reform, was a way to free the peasantry from the yoke of absentee-landlords who maintained control of the land with the collusion of the hierarchy of the church. Upon his arrival in Canada, Genik became the first Ukrainian to be employed by the Canadian government, and worked as an immigration agent taking new settlers out to their homesteads. Genik's cousin Ivan Bodrug (1874–1952) and Bodrug's friend Ivan Negrich (1875–1946) also came from the village of Bereziv in the county of Kolomyia and were qualified as primary school teachers in Galicia.[1] These three men constituted the nucleus of the intelligentsia in the Ukrainian community, and were known as the "Березівська Трійця" (romanized: Berezivs'ka Triitsya) (the "Bereziv Triumvirate"). Genik, the oldest, was the only one of the three already married. His wife Pauline (née Tsurkowsky) was the daughter of a priest, an educated woman, and they had three sons and three daughters.[3]

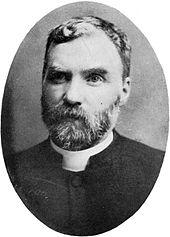

The other principal character was Bishop Seraphim, whose real name was Stefan Ustvolsky. Ustvolsky ended by being defrocked by the Russian Holy Synod in the Imperial capital of Saint Petersburg. But his story begins when, for personal reasons, he traveled to Mount Athos where he was consecrated a Bishop by the Holy Anphim, who claimed to be a bishop. The Holy Anphim ordained Ustvolsky to spite the Tsar, as at this time there was a struggle taking place between the Holy Synod and the Tsar for control of the Russian Orthodox Church (or at least this was the story he brought with him to the New World).[4]: 226 Having been consecrated a bishop, Seraphim traveled to North America, briefly staying with Ukrainian priests in Philadelphia. By the time he arrived in Winnipeg, he had no allegiances to the Russian Orthodox Church or anyone else. The Ukrainians on the prairies accepted him as a traveling holy man, a tradition which goes back to the very beginnings of Christianity.[5]

Another person who participated in the events which culminated in the creation of the Tin Can Cathedral was Seraphim's assistant Makarii Marchenko. Marchenko acted as a deacon or cantor, helping Seraphim with the church services which he knew well. He arrived with Seraphim from the United States. Archbishop Adélard Langevin, who was located in St. Boniface, was the head of the Roman Catholic diocese in Western Canada, in direct contact with Pope Pius X in Rome. He believed that his priests were more than adequate for the needs of the Ukrainian population.[6]: 184 Other players included Dr. William Patrick, head of Manitoba College, a Presbyterian college in Winnipeg; the Liberal Party of Manitoba; and Russian Orthodox missionaries with Bishop Tikhon as the Head of the Russian Orthodox Mission in North America.

Events

[edit]In 1902, a member of the Manitoba legislature, Joseph Bernier, introduced a bill "conveying properties of the Greek Ruthenian (Ukrainians were also known as Ruthenians) Church in Communion with Rome into the control of corporations under control of the Church of Rome."[6]: 189 Archbishop Langevin declared "the Ruthenians must prove themselves Catholics by turning property over to the church, and not like Protestants …to an individual or committee of laymen, independent of the priest or bishop."[7] The size of the Ukrainian population on the prairies had also attracted the interest of Russian Orthodox Missionaries. At this time the Russian Orthodox Church was spending $100,000 a year for missionary work in North America.[4]: 226 As well, the Presbyterian Church had become interested and invited young men from the Ukrainian community to attend Manitoba College (today the University of Winnipeg) where special classes were established for young Ukrainians who wished to become school teachers (and later Independent Greek Church ministers).[6]: 192 Fluent in the German language, Dr. King, the Principal of the College, interviewed the candidates Bodrug and Negrich in German. Genik translated their scholastic documents in writing from Polish into English. They became the first Ukrainian students of a university in North America – Manitoba College at this time was part of the University of Manitoba.

Genik, Bodrug, and Negrich moved quickly to try to secure their community.[8] They brought in Seraphim. He arrived in Winnipeg in April 1903[9] to set up a Church that was independent of any churches in Europe, and would have no loyalty to any of the religious interest groups vying for the souls of the new Ukrainian immigrants on the prairies. To their satisfaction, Seraphim set up an Orthodox Russian Church (not Russian Orthodox)[N 1] of which he declared himself the head, and to placate the Ukrainians it was also called the Seraphimite Church. He provided the parishioners with an Eastern Rite with which the immigrants were familiar, began to ordain cantors and deacons, and "…on 13th December 1903, a small frame building on the east side of McGregor Street between Manitoba and Pritchard Avenues, that may have been called the Holy Ghost church, was officially blessed by Seraphim and opened for worship."[10] "In November 1904 he started building his notorious 'tin can cathedral' at the corner of King Street and Stella Avenue,…"[10] made of scrap metal and wood. Charismatic, Seraphim "…ordained some 50 priests and numerous deacons, many semi-illiterate, who carried out priestly duties throughout the [Ukrainian] settlements, preaching independent Orthodoxy and trustee ownership of church property. In two years this church claimed nearly 60,000 adherents…"[11]

"Due to various indiscretions and problems with alcohol"[8] he lost the trust of the intelligentsia who had invited him to Winnipeg, and a coup took place in which they moved to get rid of him while not losing his congregation. Seraphim went to the Russian capital city of Saint Petersburg to try to get recognition and further funding from the Russian Holy Synod for the thriving Seraphimite Church. In his absence Ivan Bodrug and Ivan Negrich, already students of theology at Manitoba College, as well as priests in the Seraphimite Church, were able to obtain guarantees of Presbyterian funding for Seraphim's Church on the grounds that it would be shifted onto a Presbyterian model over the course of time. "In the late autumn of 1904, Seraphim returned from Russia, but brought no 'posobiye' with him."[12] Upon his return, he discovered the betrayal and promptly excommunicated all the priests involved in this treachery. He published pictures of them in the local newspapers with their names printed across their chests, as if they were criminals.[4]: 229 His revenge turned out to be short-lived when he received word that he had been excommunicated himself by the Russian Holy Synod: "…when the Holy Synod excommunicated Seraphim and all his priests, he left in 1908 never to return."[11]

Aftermath

[edit]

In the aftermath of this social and spiritual brushfire that swept the prairie, a Ukrainian Canadian community arose.

Ivan Bodrug, one of the mutineers in the Seraphimite Church became the head of the new Independent Church, and was quite a charismatic priest in his own right, preaching an evangelical Christianity because of the Presbyterian influence. He lived right into the 1950s. The Independent Church buildings were located on the corner of Pritchard Avenue and McGregor Street, and though the first has since been demolished – the one Seraphim used for his first Church – the second building built with Presbyterian funding still stands there today across from the Labour Temple in Winnipeg's North End.[13]

Archbishop Langevin increased his efforts to try to assimilate the Winnipeg Ukrainian community into the Roman Catholic fold. He set up the Basilian Church of St. Nicholas[14] and brought in Belgian priests, Father Achille Delaere and others, who read the Liturgy in Old Church Slavonic, dressed according to Greek ritual, and delivered sermons in Polish. The Basilian Church of St. Nicholas was across the street from the Apostolic Exarchate of Canada's Cathedral of St. Vladimir and Olga on McGregor Street in the North End of the city. Such competition provided greater opportunity for Ukrainian Canadian children to learn to speak the Ukrainian language.[4]: 229

The Liberal Party, aware that the Ukrainians were no longer allied with Archbishop Langevin and the Roman Catholics who happened to be aligned with the Conservative Party, stepped forward and funded the very first Ukrainian language newspaper in Canada, Kanadiskyi Farmer (The Canadian Farmer), of which the first editor was none other than Ivan Negrich.

Seraphim disappeared by 1908, but there are accounts of him in Ukrainskyi Holos (the Ukrainian Voice newspaper, still being published today in Winnipeg) selling Bibles to workers building railroads in British Columbia as late as 1913. In other versions of history, he returned to Russia.

Cyril Genik moved with his eldest daughter and one of his sons to the United States, to North Dakota for a time, then returned and died in 1925.

Makarii Marchenko, upon Seraphim's departure, declared himself not only the new Bishop of the Seraphimite Church, but also Arch-Patriarch, Arch-Pope, Arch-Hetman, and Arch-Prince. Not to take any chances, or show any favouritism, for good measure he excommunicated the Pope and the Russian Holy Synod.[11] There are records of him traveling the rural areas and ministering to the Ukrainians who were very much in want of their Eastern rite as late as the 1930s.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, page 170.

- ^ Franko, Ivan; Kurelek, William; Melnyk, Bohdan (1978). Fox Mykyta. Tundra Books, Montreal. ISBN 0887761127.

- ^ "Biography – GENYK, CYRIL – Volume XV (1921-1930) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Nick. Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theatre in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, Editors: Gerus, Oleh W.; Gerus-Tarnawecka, Iraida; Jarmus, Stephan, The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg.

- ^ Mitchell, Nick. The Mythology of Exile in Jewish, Mennonite and Ukrainian Canadian Writing in A Sharing of Diversities. Proceedings of the Jewish Mennonite Ukrainian Conference, "Building Bridges", General Editor: Stambrook, Fred, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1999, page 188.

- ^ a b c Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991

- ^ Winnipeg Tribune 25 February 1903.

- ^ a b Yereniuk, Roman, A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, www.uocc.ca/pdf, page 9

- ^ Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, page 190

- ^ a b Martynowych, Orest T., The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches, page 1 & 2

- ^ a b c Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903-1913, translators: Bodrug, Edward; Biddle, Lydia, Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, page xiii.

- ^ Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903-1913, translators: Bodrug, Edward; Biddle, Lydia, Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, page 81

- ^ Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, photograph 47.

- ^ Martynowych, Orest T. "St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic church" (PDF). Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies at the University of Manitoba. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903-1913, translators: Bodrug, Edward; Biddle, Lydia, Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982.

- Manitoba Free Press, issues of 10 October 1904, 20 January 1905, 28 December 1905.

- Martynowych, Orest T. (2011). The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches.

- Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991.

- Maruschak, M. The Ukrainian Canadians: A History, 2nd ed., Winnipeg: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, 1982.

- Mitchell, Nick. The Mythology of Exile in Jewish, Mennonite and Ukrainian Canadian Writing in A Sharing of Diversities, Proceedings of the Jewish Mennonite Ukrainian Conference, "Building Bridges", General Editor: Stambrook, Fred, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1999.

- Mitchell, Nick. Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theatre in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, Editors: Gerus, Oleh W.; Gerus-Tarnawecka, Iraida; Jarmus, Stephan, The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg.

- Swyripa, Frances (1984). "Canada". In Volodymyr Kubiyovych (ed.). Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 1, A–F. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 352. ISBN 0-8020-3362-8.

A unique religious experiment originated with a Russian Orthodox priest, S. Ustvolsky. As the monk Seraphim, self-proclaimed bishop and metropolitan of the Orthodox Russian church for America, he arrived in Canada in 1903 and began to ordain priests. In 1904, alarmed by Seraphim's growing eccentricities, several priests, led by I. Bodrug, broke with him and formed the Ruthenian Independent Greek church. The new church retained the Eastern rite and liturgy but was supervised and financially supported by the Presbyterian church, with which Bodrug had contacts. At its height, the Independent Greek Church claimed 60,000 adherents. It declined after 1907 when Presbyterian pressure forced genuine Protestant reform; it became part of the Presbyterian church and then of the United church. Bodrug remained within the Ukrainian evangelical movement, working closely with the Ukrainian Evangelical Alliance in North America (est. 1922). In 1931, 1.6 percent of Ukrainian Canadians were United church adherents. By 1971 intermarriage and assimilation had increased the figure to 13.9 percent, the fourth-largest denomination among Ukrainian Canadians.

- Winnipeg Tribune, issue of 25 February 1903.

- Yereniuk, Roman, A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada.

External links

[edit] Media related to Tin Can Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tin Can Cathedral at Wikimedia Commons- Православная Церковь Всероссийского Патриаршества

- Five Door Films, Romance of the Far Fur Country

- Hryniuk, Stella. "Cyril Genik". Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- Hryniuk, Stella. "Bishop Seraphim". Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- Martynowych, Orest T., The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches

- Tin Can Cathedral by Nick Mitchell

- Orysia Paszczak Tracz (1998). "Our Christmas: nothing's really changed". The Ukrainian Weekly.

- University of Manitoba Libraries: Winnipeg Building Index. Tin Can Cathedral Selkirk Avenue 1904

- Yereniuk, Roman, A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada