Viral video

Viral videos[2][3] are videos that become popular through a viral process of Internet sharing, primarily through video sharing websites such as YouTube as well as social media and email.[4][5] For a video to be shareable or spreadable, it must focus on the social logics and cultural practices that have enabled and popularized these new platforms.[6]

Viral videos may be serious, and some are deeply emotional, but many more are based more on entertainment and comedy. Notable early examples include televised comedy sketches, such as The Lonely Island's "Lazy Sunday" and "Dick in a Box", Numa Numa[7][8] videos, The Evolution of Dance,[7] Chocolate Rain[9] on YouTube; and web-only productions such as I Got a Crush... on Obama.[10] and some events that have been captured by eyewitnesses can get viral such as Battle at Kruger.[11]

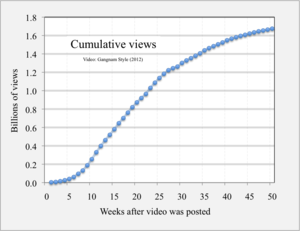

One commentator called the Kony 2012 video the most viral video in history[12] (about 34 million views in three days[13] and 100 million views in six days[14]), but "Gangnam Style" (2012) received one billion views in five months[15][16][17] and was the most viewed video on YouTube from 2012 until "Despacito" (2017).[18]

History

[edit]Videos were shared long before YouTube or even the Internet by word-of-mouth, film festivals, VHS tapes, and even to fill time gaps during the early days of cable.[19] Perhaps the earliest was Reefer Madness, a 1936 "educational" film that circulated under several different titles. It was rediscovered by Keith Stroup, founder of NORML, who circulated prints of the film around college film festivals in the 1970s. The company who produced the prints, New Line Cinema, was so successful they began producing their own films.[19] The most controversial was perhaps a clip from a newscast from Portland, Oregon in November 1970. In the clip, the disposal of a beached whale carcass by dynamite is documented, including the horrific aftermath of falling mist and chunks since the exclusion zone was not big enough.[20] The exploding whale story obtained urban legend status in the Northwest and gained new interest in 1990 after Dave Barry wrote a humorous column about the event,[21] leading to copies being distributed over bulletin board systems around 1994.[22]

The "humorous home video" genre dates back at least to 1963, when the TV series "Your Funny, Funny Films"[23] debuted. The series showcased amusing film clips, mostly shot on 8mm equipment by amateurs. The idea was revived in 1989 with America's Funniest Home Videos, a series described by an ABC executive as a one-time "reality-based filler special" that was inspired by a segment of a Japanese variety show, Fun With Ken and Kaito Chan, borrowing clips from various Japanese home video shows as well.[24] Now[timeframe?] the longest-running primetime entertainment show in the history of ABC, the show's format includes showing clips of home videos sent in to the show's committee, and then the clips are voted on by a live filmed audience, with the winners awarded a monetary prize.[25]

During the internet's public infancy, the 1996 Seinfeld episode "The Little Kicks" addresses the distribution of a viral video through non-online, non-broadcast means. It concludes with the citizens of New York City having individually witnessed Elaine's terrible dancing via a bootleg copy of a feature film, establishing that the dancing footage had effectively gone viral.

Viral videos began circulating as animated GIFs small enough to be uploaded to websites over dial-up Internet access or through email as attachments in the early 1990s.[26] Videos were also spread on message boards, P2P file sharing sites, and even coverage from mainstream news networks on television.[27] Two of the most successful viral videos of the early internet era were "The Spirit of Christmas" and "Dancing Baby". "The Spirit of Christmas" surfaced in 1995, spread through bootleg copies on VHS and on the internet, as well as an AVI file on the PlayStation game disc for Tiger Woods 99, later leading to a recall.[27][28] The popularity of the videos led to the creation of the television series South Park after it was picked up by Comedy Central.[29] "Dancing Baby", a 3D-rendered dancing baby video made in 1996 by the creators of Character Studio for 3D Studio MAX, became something of a mid-late 1990s cultural icon in part due to its exposure on worldwide commercials, editorials about Character Studio, and the popular television series Ally McBeal.[29][30][31] The video may have first spread when Ron Lussier, the animator who cleaned up the raw animation, began passing the video around his workplace, LucasArts.[32]

Later distribution of viral videos on the internet before YouTube, which was created in 2005 and bought by Google in 2006, were mostly through websites dedicated to hosting humorous content, such as Newgrounds and YTMND, although message boards such as eBaum's World and Something Awful were also instrumental.[27] Notably, some content creators hosted their content on their own websites, such as Joel Veitch's site for his band Rather Good, which hosted quirky Flash videos for the band's songs; the most popular was "We Like the Moon", whose viral popularity on the internet prompted Quiznos to parody the song for a commercial.[33] The most famous self-hosted home of viral videos is perhaps Homestar Runner, released in the early 2000’s and is still running today[27] In the mid 2000’s more social media websites such as Facebook (2004)[1] and Twitter (2006)[2] gave users the option to share videos causing them to go viral. More recently, there has been a surge in viral videos on video sharing sites such as YouTube, partially because of the availability of affordable digital cameras.[34] Beginning in December 2015, YouTube introduced a "trending" tab to alert users to viral videos using an algorithm based on comments, views, "external references", and even location.[35] The feature reportedly does not use viewing history to serve up related content, and the content may be curated by YouTube.[36]

Modern viral videos tend to come from TikTok (rebrand of Musical.ly since 2018)[3] and Instagram (2012) [4], TikTok hosts short form content in a portrait format, these short videos are often meant to be humorous, while others focus mainly on music, viral videos commonly came from music related short videos and popular dances, TikTok was a large internet sensation [5] causing many viral videos to be made.

Qualification

[edit]

There are several ways to gauge whether a video has "gone viral". The statistic perhaps most mentioned is number of views, and as sharing has become easier, the threshold requirement of sheer number of views has increased. YouTube personality Kevin Nalty (known as Nalts) recalls on his blog: "A few years ago, a video could be considered 'viral' if it hit a million views", but says as of 2011, only "if it gets more than 5 million views in a 3–7-day period" can it be considered "viral".[37][38] To compare, 2004's Numa Numa received two million hits on Newgrounds in its first three months (a figure explained in a 2015 article as "a staggering number for the time").[27]

Nalts also posits three other considerations: buzz, parody, and longevity,[37] which are more complex ways of judging a viral video's views. Buzz addresses the heart of the issue; the more a video is shared, the more discussion the video creates both online and offline. What he emphasizes is notable is that the more buzz a video gets, the more views it gets. A study on viral videos by Carnegie Mellon University found that the popularity of the uploader affected whether a video would become viral,[39] and having the video shared by a popular source such as a celebrity or a news channel also increases buzz.[37] It is also part of the algorithm YouTube uses to predict popular videos.[35] Parodies, spoofs and spin-offs often indicate a popular video, with long-popular video view counts given with original video view counts as well as additional view counts given for the parodies. Longevity indicates if a video has remained part of the Zeitgeist.

Reasons for popularity

[edit]Due to their societal impact and marketability, viral videos attract attention in both advertising and academia, which try to account for the reason viral videos are spread and what will make a video go viral. Several theories exist.

A viral video's longevity often relies on a hook which draws the audience to watch it. The hook, often a memorable phrase or moment, is able to become a part of the viral video culture after being shown repeatedly. The hooks, or key signifiers, are not able to be predicted before the videos become viral.[40] The early view pattern of a viral video can be used to forecast its peak day in future.[5] Notable examples include "All your base are belong to us", based on the poorly translated video game Zero Wing, which was first distributed in 2000 as a GIF animation and became popular for the grammatically incorrect hook of its title, and Don Hertzfeldt's 2000 Academy Awards Best Animated Short Film nomination "Rejected" with the quotable hooks "I am a banana" and "My spoon is too big!"[41] Another early video was the Flash animation "The End of the World", created by Jason Windsor and uploaded to Albino Blacksheep in 2003, with quotable hooks such as "but I'm le tired" and "WTF, mates?"[41][42]

Rosanna Guadagno, a social psychologist at the University of Texas at Dallas, found in a study that people preferred to share a funny video rather than one of a man treating his own spider bite, and overall they were more likely to share any video that evoked an intense emotional response.[43] Two professors at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania also found that uplifting stories were more likely to be shared on the New York Times' web site than disheartening ones.[43]

Others postulate that sharing is driven by ego in order to build up an online persona for oneself. Chartbeat, a company that measures online traffic, compiled data comparing the amount of time spent reading an article and the number of times it was shared and found that people often post articles on Twitter they haven't even read.[43]

Categories by subject

[edit]Band and music promotion

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2015) |

Many independent musicians, as well as large companies such as Universal Music Group, use YouTube to promote videos. Six of the 10 most viral YouTube videos of 2015 were rooted in music.[44]

One such video, the "Free Hugs Campaign" with accompanying music by the Sick Puppies, was one of the winners of the 2006 YouTube Awards.[45] However, the awards received criticism over the voting process and accused of bias.[46] However, the main character of the video, Juan Mann, received positive recognition after being interviewed on Australian news programs and appearing on The Oprah Winfrey Show.[47]

Education

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2015) |

Viral videos continue to increase in popularity as teaching and instructive aids. In March 2007, an elementary school teacher, Jason Smith, created TeacherTube, a website for sharing educational videos with other teachers. The site now features over 54,000 videos.[48] Some college curricula are now using viral videos in the classroom as well. As of 2009,[update] Northwestern University offers a course called "YouTubing 101". The course invites students to produce their own viral videos, focusing on marketing techniques and advertising strategies.[49]

Customer complaints

[edit]"United Breaks Guitars", by the Canadian folk rock music group Sons of Maxwell, is an example of how viral videos can be used by consumers to pressure companies to settle complaints.[50] Another example is Brian Finkelstein's video complaint to Comcast, 2006. Finkelstein recorded a video of a Comcast technician sleeping on his couch. The technician had come to repair Brian's modem but had to call Comcast's central office and fell asleep after being placed on hold waiting for Comcast.[51][52]

Cyberbullying

[edit]The Canadian high school student known as Star Wars Kid was subjected to significant harassment and ostracizing after the viral success of his video (first uploaded to the Internet on the evening of 14 April 2003).[53] His family accepted a financial settlement after suing the individuals responsible for posting the video online.[54]

In July 2010, an 11-year-old child with the pseudonym "Jessi Slaughter" was subjected to a campaign of harassment and cyberbullying following the viral nature of videos they had uploaded to Stickam and YouTube. As a result of the case, the potential for cyberbullying as a result of viral videos was widely discussed in the media.[55][56]

Police misconduct

[edit]The Chicago Tribune reported that in 2015, nearly 1,000 civilians in the United States were shot and killed by police officers—whether the officers responsible were justified is now often publicly called into question in the age of viral videos.[57] As more people are uploading videos of their encounters with police, more departments are encouraging their officers to wear body cameras.[58] The procedure for releasing such video is currently evolving and could potentially incriminate more suspects than officers, although current waiting times of several months to release such videos appear to be attempted cover-ups of police mistakes.[59] In October 2015, then-FBI Director James Comey remarked in a speech at the University of Chicago Law School that the increased attention on police in light of recent viral videos showing police involved in fatal shootings has made officers less aggressive and emboldened criminals. Comey has acknowledged that there are no data to back up his assertion; according to him, viral videos are one of many possible factors such as cheaper drugs and more criminals being released from prison. Other top officials at the Justice Department have stated that they do not believe increased scrutiny of officers has increased crime.[60]

Two videos went viral in October 2015 of a white school police officer assaulting an African-American student. The videos, apparently taken with cell phones by other students in the classroom, were picked up by local news outlets and then further spread by social media.[61]

Dash cam videos of the Chicago police murder of Laquan McDonald were released after 14 months of being kept sealed, which went viral and sparked further questions about police actions. Chicago's mayor, Rahm Emanuel, fired Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy and there have also been demands for Emanuel to resign.[62] A similar case, in which Chicago police attempted to suppress a dash cam video of the shooting of Ronald Johnson by an officer, is currently part of an ongoing federal lawsuit against the city.[63]

Political implications

[edit]The 2008 United States presidential election showcased the impact of political viral videos. For the first time, YouTube hosted the CNN-YouTube presidential debates, calling on YouTube users to pose questions. In this debate, the opinions of viral video creators and users were taken seriously. There were several memorable viral videos that appeared during the campaign. In June 2007, "I Got a Crush... on Obama", a music video featuring a girl claiming to have a crush on presidential candidate Barack Obama, appeared. Unlike previously popular political videos, it did not feature any celebrities and was purely user-generated. The video garnered many viewers and gained attention in the mainstream media.[64]

YouTube became a powerful source of campaigning for the 2008 Presidential Election. Every major party candidate had their own YouTube channel in order to communicate with the voters, with John McCain posting over 300 videos and Barack Obama posting over 1,800 videos. The music video "Yes We Can" by will.i.am demonstrates user-generated publicity for the 2008 Presidential Campaign. The video depicts many celebrities as well as black and white clips of Barack Obama. This music video inspired many parodies and won an Emmy for Best New Approaches in Daytime Entertainment.[65]

The proliferation of viral videos in the 2008 campaign highlights the fact that people increasingly turn to the internet to receive their news. In a study for the Pew Research Center in 2008, approximately 2% of the participants said that they received their news from non-traditional sources such as MySpace or YouTube.[66] The campaign was widely seen as an example of the growing influence of the internet on United States politics, a point further evidenced by the founding of viral video producers like Brave New Films.[67]

During the 2012 United States presidential election, "Obama Style" and "Mitt Romney Style", the parodies of Gangnam Style, both peaked on Election Day and received approximately 30 million views within one month before Election Day.[5] "Mitt Romney Style", which negatively portrays Mitt as an affluent, extravagant, and arrogant businessman, received an order of magnitude views more than "Obama Style".[citation needed]

Financial implications

[edit]The web traffic gained by viral videos allows for advertising revenue. The YouTube website is monetized by selling and showing advertising. According to the New York Times, YouTube uses an algorithm called "reference rank" to evaluate the viral potential of videos posted to the site. Using evidence from as few as 10,000 views, it can assess the probability that the video will go viral. Before YouTube implemented wide-scale revenue sharing, if it deemed the video a viable candidate for advertising, it contacted the original poster by e-mail and offered a profit-sharing contract. By this means, such videos as "David After Dentist" have earned more than $100,000 for their owners.[68] One successful YouTube video creator, Andrew Grantham, whose "Ultimate Dog Tease" had been viewed more than 170,000,000 times (as of June 2015), entered an agreement with Paramount Pictures in February 2012 for the development of a feature film. The film was to be written by Alec Berg and David Mandel.[69] Pop stars such as Justin Bieber and Esmée Denters also started their careers via YouTube videos which ultimately went viral. By 2014, pop stars such as Miley Cyrus, Eminem, and Katy Perry were regularly obtaining web traffic in the order of 120 to 150 million hits a month, numbers far in excess of what many viral videos receive.

Companies also use viral videos as a type of marketing strategy. The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty is considered to have been one of the first viral marketing strategies to hit the world when Dove released their Evolution video in 2006.[70] Their online campaign continued to generate viral videos when Real Beauty Sketches was released in 2013 and spread all throughout social media, especially Facebook and Twitter.

Notable sites

[edit]- Albino Blacksheep

- Break.com (defunct)

- BuzzFeed

- eBaum's World (defunct)

- Fail Blog (defunct)

- Google Video (defunct)

- JibJab

- LiveLeak (defunct)

- Metacafe (defunct)

- Newgrounds

- Nico Nico Douga

- TikTok

- Upworthy

- Vine (defunct)

- Veoh.com (defunct)

- VT (Viral Thread) (defunct)

- WorldStar HipHop

- YouTube

- YTMND

See also

[edit]- Internet meme

- List of Internet phenomena

- List of viral videos

- Positive feedback

- Seeding agency

- Shock site

- Streisand effect

- Viral marketing

References

[edit]- ^ a b Raw data accessed 2 September 2018 from Wayback Machine archives of YouTube video page Archived 26 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine stored by archive.org (click on year 2012 or 2013).

- ^ "What Does Going Viral Online Really Mean?". Lifewire. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Oxford Languages | The Home of Language Data". languages.oup.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Definition of 'viral video'[permanent dead link]". PC Mag Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 December 2012. Updated link: https://www.pcmag.com/encyclopedia/term/viral-video Archived 14 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Lu Jiang, Yajie Miao, Yi Yang, ZhenZhong Lan, Alexander Hauptmann. Viral Video Style: A Closer Look at Viral Videos on YouTube. Retrieved 30 March 2016. Paper: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~lujiang/camera_ready_papers/ICMR2014-Viral.pdf Archived 26 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine Slides: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~lujiang/resources/ViralVideos.pdf Archived 26 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (2013). Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. NYU Press. p. 3.

- ^ a b "How YouTube made superstars out of everyday people Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine". 11 April 2010. The Guardian.

- ^ "Guardian Viral Video Chart Archived 4 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine". 8 June 2007. The Guardian.

- ^ Murphy, Meagan (22 September 2010). "'Numa Numa Guy' Fronting Band, Still Single ". FOX411.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (13 June 2007). "Music Video Has a 'Crush on Obama' Archived 16 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine". ABC News. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ BBC News states "Almost 9.5m people have already watched the video, dubbed the Battle at Kruger, which was filmed by US tourist Dave Budzinski while he was on a guided safari." Published 9 Aug 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2016 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/6938516.stm Archived 29 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Flock, Elizabeth (4 April 2012). "Kony 2012 screening in Uganda met with anger, rocks thrown at screen". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ * "Kony 2012: What's the story". The Guardian. 8 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Quilty-Harper, Conrad (9 March 2012). "Kony 2010 Stats breakdown of the viral video". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

over 50 million views

- Quilty-Harper, Conrad (9 March 2012). "Kony 2010 Stats breakdown of the viral video". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Kony most viral". Mashable. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "How 'Gangnam Style' Went Viral [Graphic]". Scientific American. 1 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Weng, Lilian; Menczer, Filippo; Ahn, Yong-Yeol (2013). "Virality Prediction and Community Structure in Social Networks". Scientific Reports. 3: 2522. arXiv:1306.0158. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E2522W. doi:10.1038/srep02522. PMC 3755286. PMID 23982106.

- ^ Laird, Sam (5 September 2012). "Gangnam Style! The Anatomy of a Viral Sensation [INFOGRAPHIC]". Mashable. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "YouTube's 10 years of hits: Global recognition at last for Rick Astley". The Register. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Long before the viral video or 'breaking the internet', there was the exploding whale Archived 5 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine". 13 November 2015. 9News.com.au. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Barry, Dave (20 May 1990). "Thar She Blows". The Washington Post.[dead link]

- ^ Harriet Baskas (6 January 2010). Oregon Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities, and Other Offbeat Stuff. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7627-6201-9.

- ^ "Your Funny, Funny Films". IMDb. 8 July 1963. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Wiener-Bronner, Danielle (21 October 2015) "The internet was supposed to kill 'America’s Funniest Home Videos.' Instead, it’s reviving it Archived 3 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine." Fusion. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Lindenbaum, Sybil (25 November 2015). "America's Funniest Home Videos Content Conquers Social Media With a Landmark 10 Million Subscribers Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine". PR Newswire. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Brown, Damon (13 September 2010). "Celebrating the Web's earliest viral hits Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine". CNN. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Merrill, Brad (17 June 2015). "Here’s How Videos Went Viral Before YouTube And Social Media Archived 27 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine". Make Use Of. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "Tiger Woods Game Pulled Archived 15 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine." 15 January 1999. IGN. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ a b "The history of viral video". Tuscoloosa News. 6 June 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ McNamara, Paul (16 June 1997). "Baby talk: This twisting tot is all the rage on the 'Net". Network World. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Lefevre, Greg (19 January 1998) "Dancing Baby cha-chas from the Internet to the networks" Archived 7 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine. CNN.

- ^ Lussier, Ron (2005). "Dancing Baby FAQ". Burning Pixel Productions. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Fine, Jon (16 February 2004). "Pop culture: Veitch's critters hit big in Quiznos spots Archived 21 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Advertising Age. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (24 April 2006). "How to get famous in 3500 seconds". Time.

- ^ a b Southern, Matt (10 December 2015). "YouTube Introduces a 'Trending' Tab, Surfacing Viral Videos in Real Time Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine". Search Engine Journal. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Cox, Jamieson (9 December 2015). "YouTube is making it easier to find viral videos Archived 16 April 2024 at the Wayback Machine". The Verge. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b c O'Neill, Megan (9 May 2011). "What Makes A Video 'Viral'? Archived 7 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine" AdWeek. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Nalts (pseudonym) (6 May 2011). "How many views do you need to be viral? Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine" Will Video for Food (blog). Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "Characteristics – CMU Viral Videos". Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Burgess, Jean (2008).'All Your Chocolate Rain Are Belong to Us?' Viral Video, YouTube, and the Dynamics of Participatory Culture Archived 27 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine "Video Vortex Reader: Responses to YouTube". Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, pp. 101–109.

- ^ a b Moreau, Elise (30 October 2014). "10 Videos That Went Viral Before YouTube Even Existed Archived 4 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine". About Tech. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Peters, Lucia. "7 Incredibly Weird Viral Videos From The Early 2000s The Internet Was Inexplicably Obsessed With Archived 5 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine". Bustle. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Kitroeff, Natalie (19 May 2014). "Why That Video Went Viral Archived 4 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh (16 December 2015). "YouTube's Most Viral Videos Of 2015 Are All About Music Archived 3 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine". Forbes. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "YouTube names best video winners Archived 30 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Heffernan, Virginia (27 March 2007). "YouTube Awards the Top of Its Heap Archived 1 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Free Hugs on The Oprah Winfrey Show (30 October 2006): "Thanks to a video on the website YouTube, Juan's movement is spreading worldwide—he is even organizing a global hug day!" Oprah.com Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Katherine Leal Unmuth, Dallasnews.com Archived 10 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine[full citation needed]

- ^ Leopold, Wendy (19 March 2009). "YouTubing 101: Northwestern Offers Course on Viral Videos Archived 18 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine" (press release). Northwestern University. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Cheryl V. (9 July 2009). "Passenger uses YouTube to get United's attention". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ^ Stross, Randall (2 July 2006). "AOL Said, 'If You Leave Me I'll Do Something Crazy'. Archived 21 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine" The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2015. "The technician, in Washington, had arrived at Brian Finkelstein's home to replace a faulty modem and had to call in to Comcast's central office. Placed on hold just like powerless customers, the technician fell asleep after an hour of waiting."

- ^ Suri, Sabena (26 June 2006). "Sleepy Comcast technician gets filmed, then fired Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine". CNET. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Ha, Tu Thanh. "'Star Wars Kid' cuts a deal with his tormentors"; The Globe and Mail; 7 April 2006.

- ^ Wei, Will (12 May 2010). "Where Are They Now? The 'Star Wars Kid' Sued The People Who Made Him Famous Archived 22 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine". Business Insider. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Simon, Marie (22 July 2010). "Jessi Slaughter, nouvelle tête de turc du web américain". L'Express (in French). Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Farquhar, Peter (20 July 2010). "Jessi Slaughter and the 4chan trolls – the case for censoring the internet". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Kindy, Kimberly; Fisher, Marc; Tate, Julie; Jenkins, Jennifer (26 December 2015). "For police nationwide, a year of reckoning: Officers fatally shoot nearly 1,000". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015 – via Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Hellgren, Mike (23 December 2015). "Baltimore Co. Police Review Officer's Actions After Viral Video Surfaces". CBS Baltimore. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "Viral videos wrongly hurt reputations of vast majority of police". Herald-Whig. 23 December 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Alcindor, Yamiche (24 October 2015). "FBI director links 'viral videos' of police to rise in violence". USA Today. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Fausset, Richard; Southall, Ashely (26 October 2015). "Video Shows Officer Flipping Student in South Carolina, Prompting Inquiry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Graham, David A. (1 December 2015). "The Firing of Chicago Police Chief Garry McCarthy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Meisner, Jason; Walberg, Matthew (2 December 2015). "City wavering on keeping video secret in another fatal Chicago police shooting". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine (15 June 2007). "A Hit Shows Big Interest in Racy Material – and Obama" (Web). The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ Wallsten, Kevin (2010). "Yes We Can": How Online Viewership, Blog Discussion, Campaign Statements, and Mainstream Media Coverage Produced a Viral Video Phenomenon Archived 28 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Information Technology and Politics.

- ^ Kohut, Andrew (11 January 2008). "The Internet's Broader Role in Campaign 2008". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (Web) on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim (29 June 2008). "Political Freelancers Use Web to Join the Attack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Cain Miller, Claire (26 October 2011). "Cashing in on Your Hit YouTube Video". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ McNary, Dave (13 February 2012). "Paramount inks scribe duo for canine romp: Project based on YouTube 'Dog Tease' video" Archived 18 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Bahadur, Nina (21 January 2014). "How Dove Tried To Change The Conversation About Female Beauty". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Viral videos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Viral videos at Wikimedia Commons- CMU Viral Videos A public data set for viral video study.

- Viral Video Chart Guardian News, UK.

- Photos Gone Viral! Archived 25 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine — slideshow by Life magazine

- YouTube 'Rewind' – YouTube's page covering their top-viewed videos by year and brief information on their spread.

- The Worlds of Viral Video Documentary produced by Off Book (web series)