Tea Party movement

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. The movement formed in opposition to the policies of Democratic President Barack Obama[1][2] and was a major factor in the 2010 wave election[3][4] in which Republicans gained 63 House seats[5] and took control of the U.S. House of Representatives.[6]

Participants in the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[7][8] The movement supported small-government principles[9][10] and opposed the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare), President Obama's signature health care legislation.[11][12][13] The Tea Party movement has been described as both a popular constitutional movement[14] and as an "astroturf movement" purporting to be spontaneous and grassroots, but created by hidden elite interests.[15][16] The movement was composed of a mixture of libertarian,[17] right-wing populist,[18] and conservative activism.[19] It sponsored multiple protests and supported various political candidates since 2009.[20][21][22] According to the American Enterprise Institute, various polls in 2013 estimated that slightly over 10% of Americans identified as part of the movement.[23] The movement took its name from the December 1773 Boston Tea Party, a watershed event in the American Revolution, with some movement adherents using Revolutionary era costumes.[24]

The Tea Party movement was popularly launched following a February 19, 2009, call by CNBC reporter Rick Santelli on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange for a "tea party".[25][26] On February 20, 2009, The Nationwide Tea Party Coalition also helped launch the Tea Party movement via a conference call attended by around 50 conservative activists.[27][28] Supporters of the movement subsequently had a major impact on the internal politics of the Republican Party. While the Tea Party was not a political party in the strict sense, research published in 2016 suggests that members of the Tea Party Caucus voted like a right-wing third party in Congress.[29] A major force behind the movement was Americans for Prosperity (AFP), a conservative political advocacy group founded by businessman and political activist David Koch.[30]

By 2016, Politico wrote that the Tea Party movement had died; however, it also said that this was in part because some of its ideas had been absorbed by the mainstream Republican Party.[31] CNBC reported in 2019 that the conservative wing of the Republican Party "has basically shed the tea party moniker".[32]

Agenda

The Tea Party movement focuses on a significant reduction in the size and scope of the government.[9] The movement advocates a national economy operating without government oversight.[33] Movement goals include limiting the size of the federal government, reducing government spending, lowering the national debt and opposing tax increases.[34] To this end, Tea Party groups have protested the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), stimulus programs such as Barack Obama's American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA, commonly referred to as the Stimulus or The Recovery Act), cap and trade environmental regulations, health care reform such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, also known simply as the Affordable Care Act or "Obamacare") and perceived attacks by the federal government on their 1st, 2nd, 4th and 10th Amendment rights.[35] Tea Party groups have also voiced support for right to work legislation as well as tighter border security, and opposed amnesty for illegal immigrants.[36][37] On the federal health care reform law, they began to work at the state level to nullify the law, after the Republican Party lost seats in Congress and the Presidency in the 2012 elections.[38][39] It has also mobilized locally against the United Nations Agenda 21.[38][40] They have protested the IRS for controversial treatment of groups with "tea party" in their names.[41] They have formed Super PACs to support candidates sympathetic to their goals and have opposed what they call the "Republican establishment" candidates.

The Tea Party does not have a single uniform agenda. The decentralized character of the Tea Party, with its lack of formal structure or hierarchy, allows each autonomous group to set its own priorities and goals. Goals may conflict, and priorities will often differ between groups. Many Tea Party organizers see this as a strength rather than a weakness, as decentralization has helped to immunize the Tea Party against co-opting by outside entities and corruption from within.[42]

Even though the groups participating in the movement have a wide range of different goals, the Tea Party places its view of the Constitution at the center of its reform agenda.[34][43][44] It urges the return of government as intended by some of the Founding Fathers. It also seeks to teach its view of the Constitution and other founding documents.[42] Scholars have described its interpretation variously as originalist, popular,[45] or a unique combination of the two.[43][46] Reliance on the Constitution is selective and inconsistent. Adherents cite it, yet do so more as a cultural reference rather than out of commitment to the text, which they seek to alter.[47][48][49] Two constitutional amendments have been targeted by some in the movement for full or partial repeal: the 16th that allows an income tax, and the 17th that requires popular election of senators. There has also been support for a proposed Repeal Amendment, which would enable a two-thirds majority of the states to repeal federal laws, and a Balanced Budget Amendment, to limit deficit spending.[34]

The Tea Party has sought to avoid placing emphasis on traditional conservative social issues. National Tea Party organizations, such as the Tea Party Patriots and FreedomWorks, have expressed concern that engaging in social issues would be divisive.[42] Instead, they have sought to have activists focus their efforts away from social issues and focus on economic and limited government issues.[50][51][52] Still, many groups like Glenn Beck's 9/12 Tea Parties, TeaParty.org, the Iowa Tea Party and Delaware Patriot Organizations do act on social issues such as abortion, gun control, prayer in schools, and illegal immigration.[50][51][53]

One attempt at forming a list of what Tea Partiers wanted Congress to do resulted in the Contract from America. It was a legislative agenda created by conservative activist Ryan Hecker with the assistance of Dick Armey of FreedomWorks. Armey had co-written with Newt Gingrich the previous Contract with America released by the Republican Party during the 1994 midterm elections. One thousand agenda ideas that had been submitted were narrowed down to twenty-one non-social issues. Participants then voted in an online campaign in which they were asked to select their favorite policy planks. The results were released as a ten-point Tea Party platform.[54][55] The Contract from America was met with some support within the Republican Party, but it was not broadly embraced by GOP leadership, which released its own 'Pledge to America'.[55]

In the aftermath of the 2012 American elections, some Tea Party activists have taken up more traditionally populist ideological viewpoints on issues that are distinct from general conservative views. Examples are various Tea Party demonstrators sometimes coming out in favor of U.S. immigration reform as well as for raising the U.S. minimum wage.[56] [dead link]

Foreign policy

Historian and writer Walter Russell Mead analyzes the foreign policy views of the Tea Party movement in a 2011 essay published in Foreign Affairs. Mead says that Jacksonian populists, such as the Tea Party, combine a belief in American exceptionalism and its role in the world with skepticism of American's "ability to create a liberal world order". When necessary, they favor "total war" and unconditional surrender over "limited wars for limited goals". Mead identifies two main trends, one personified by former Texas Congressman Ron Paul and the other by former Governor of Alaska Sarah Palin. "Paulites" have a Jeffersonian approach that seeks, if possible, to avoid foreign military involvement. "Palinites", while seeking to avoid being drawn into unnecessary conflicts, favor a more aggressive response to maintaining America's primacy in international relations. Mead says that both groups share a distaste for "liberal internationalism".[57]

Some Tea Party-affiliated Republicans, such as Michele Bachmann, Jeff Duncan, Connie Mack IV, Jeff Flake, Tim Scott, Joe Walsh, Allen West, and Jason Chaffetz, voted for progressive Congressman Dennis Kucinich's resolution to withdraw U.S. military personnel from Libya.[58] In the Senate, three Tea Party backed Republicans, Jim DeMint, Mike Lee and Michael Crapo, voted to limit foreign aid to Libya, Pakistan and Egypt.[59] Tea Partiers in both houses of Congress have shown willingness to cut foreign aid. Most leading figures within the Tea Party both within and outside Congress opposed military intervention in Syria.[60][61]

Organization

The Tea Party movement is composed of a loose affiliation of national and local groups that determine their own platforms and agendas without central leadership. The Tea Party movement has both been cited as an example of grassroots political activity and has also been described as an example of corporate-funded activity made to appear as spontaneous community action, a practice known as "astroturfing".[62][63][64][65][66][67] Other observers see the organization as having its grassroots element "amplified by the right-wing media", supported by elite funding.[47][68]

The Tea Party movement is not a national political party; polls show that most Tea Partiers consider themselves to be Republicans[69][70] and the movement's supporters have tended to endorse Republican candidates.[71] Commentators, including Gallup editor-in-chief Frank Newport, have suggested that the movement is not a new political group but simply a re-branding of traditional Republican candidates and policies.[69][72][73] An October 2010 Washington Post canvass of local Tea Party organizers found 87% saying "dissatisfaction with mainstream Republican Party leaders" was "an important factor in the support the group has received so far".[74]

Tea Party activists have expressed support for Republican politicians Sarah Palin, Dick Armey, Michele Bachmann, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz.[citation needed] In July 2010, Bachmann formed the Tea Party Congressional Caucus;[75] however, since July 16, 2012, the caucus has been defunct.[76] An article in Politico reported that many Tea Party activists were skeptical of the caucus, seeing it as an effort by the Republican Party to hijack the movement. Utah congressman Jason Chaffetz refused to join the caucus, saying

Structure and formality are the exact opposite of what the Tea Party is, and if there is an attempt to put structure and formality around it, or to co-opt it by Washington, D.C., it's going to take away from the free-flowing nature of the true Tea Party movement.[77]

Etymology

The name "Tea Party" is a reference to the Boston Tea Party, a protest in 1773 by colonists who objected to British taxation without representation, and demonstrated by dumping British tea taken from docked ships into the harbor. The event was one of the first in a series that led to the United States Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution that gave birth to American independence.[78] Some commentators have referred to the Tea in "Tea Party" as the backronym "Taxed Enough Already", though this did not appear until months after the first nationwide protests.[79]

History

Background

References to the Boston Tea Party were part of Tax Day protests held in the 1990s and before.[24][81][82][83] In 1984, David H. Koch and Charles G. Koch of Koch Industries founded Citizens for a Sound Economy (CSE), a conservative political group whose self-described mission was "to fight for less government, lower taxes, and less regulation." Congressman Ron Paul was appointed as the first chairman of the organization. The CSE lobbied for policies favorable to corporations, particularly tobacco companies.[84]

In 2002, a Tea Party website was designed and published by the CSE at web address www.usteaparty.com, and stated "our US Tea Party is a national event, hosted continuously online and open to all Americans who feel our taxes are too high and the tax code is too complicated."[85][86] The site did not take off at the time.[87] In 2003, Dick Armey became the chairman of CSE after retiring from Congress.[88] In 2004, Citizens for a Sound Economy split into FreedomWorks, for 501c4 advocacy activity, and the Americans for Prosperity Foundation. Dick Armey stayed as chairman of FreedomWorks, while David Koch stayed as Chairman of the Americans for Prosperity Foundation. The two organizations would become key players in the Tea Party movement from 2009 onward.[89][90] Americans for Prosperity and FreedomWorks were "probably the leading partners" in the September 2009 Taxpayer March on Washington, also known as the "9/12 Tea Party", according to The Guardian.[91]

Commentaries on origin

Fox News Channel commentator Juan Williams has said that the Tea Party movement emerged from the "ashes" of Ron Paul's 2008 presidential primary campaign.[92] Indeed, Ron Paul has stated that its origin was on December 16, 2007, when supporters held a 24-hour record breaking, "moneybomb" fundraising event on the Boston Tea Party's 234th anniversary,[93] but that others, including Republicans, took over and changed some of the movement's core beliefs.[94][95] Writing for Slate.com, Dave Weigel has argued in concurrence that, in his view, the "first modern Tea Party events occurred in December 2007, long before Barack Obama took office, and they were organized by supporters of Rep. Ron Paul," with the movement expanding and gaining prominence in 2009.[73] (Barack Obama took office in January 2009.) Journalist Joshua Green has stated in The Atlantic that while Ron Paul is not the Tea Party's founder, or its culturally resonant figure, he has become the "intellectual godfather" of the movement since many now agree with his long-held beliefs.[96]

Journalist Jane Mayer has said that the Koch brothers were essential in funding and strengthening the movement, through groups such as Americans for Prosperity.[90] In 2013, a study published in the journal Tobacco Control concluded that organizations within the movement were connected with non-profit organizations that the tobacco industry and other corporate interests worked with and provided funding for,[85][97] including the group Citizens for a Sound Economy.[98] Al Gore cited the study and said that the connections between "market fundamentalists", the tobacco industry and the Tea Party could be traced to a 1971 memo from tobacco lawyer Lewis F. Powell, Jr. who advocated more political power for corporations. Gore said that the Tea Party is an extension of this political strategy "to promote corporate profit at the expense of the public good."[99]

Former governor of Alaska and vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, keynoting a Tea Party Tax Day protest at the state capital in Madison, Wisconsin on April 15, 2011, reflected on the origins of the Tea Party movement and credited President Barack Obama, saying "And speaking of President Obama, I think we ought to pay tribute to him today at this Tax Day Tea Party because really he's the inspiration for why we're here today. That's right. The Tea Party Movement wouldn't exist without Barack Obama."[100][101]

Charles Homans of The New York Times said that the Tea Party arose in response to the "unpopularity of the George W. Bush administration", which caused "a moment of crisis for the Republican Party."[102]

Early local protest events

On January 24, 2009, Trevor Leach, chairman of the Young Americans for Liberty in New York State, organized the Binghamton Tea Party, to protest obesity taxes proposed by New York Governor David Paterson and call for fiscal responsibility on the part of the government.[103] The protestors emptied bottles of soda into the Susquehanna River, and several of them wore Native American headdresses, similar to the band of 18th century colonists who dumped tea in Boston Harbor to express outrage about British taxes.[104]

Some of the protests were partially in response to several federal laws: the Bush administration's Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008,[105] and the Obama administration's economic stimulus package the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009[106] and healthcare reform legislation.[11]

New York Times journalist Kate Zernike reported that leaders within the Tea Party credit Seattle blogger and conservative activist Keli Carender with organizing the first Tea Party in February 2009, although the term "Tea Party" was not used.[107] Other articles, written by Chris Good of The Atlantic[108] and NPR's Martin Kaste,[109] credit Carender as "one of the first" Tea Party organizers and state that she "organized some of the earliest Tea Party-style protests".

Carender first organized what she called a "Porkulus Protest" in Seattle on Presidents Day, February 16, the day before President Barack Obama signed the stimulus bill into law.[110] Carender said she did it without support from outside groups or city officials. "I just got fed up and planned it." Carender said 120 people participated. "Which is amazing for the bluest of blue cities I live in, and on only four days notice! This was due to me spending the entire four days calling and emailing every person, think tank, policy center, university professors (that were sympathetic), etc. in town, and not stopping until the day came."[107][111]

Contacted by Carender, Steve Beren promoted the event on his blog four days before the protest[112] and agreed to be a speaker at the rally.[113] Carender also contacted conservative author and Fox News Channel contributor Michelle Malkin, and asked her to publicize the rally on her blog, which Malkin did the day before the event.[114] The following day, the Colorado branch of Americans for Prosperity held a protest at the Colorado Capitol, also promoted by Malkin.[115] Carender held a second protest on February 27, 2009, reporting "We more than doubled our attendance at this one."[107]

First national protests and birth of national movement

On February 18, 2009, the one-month old Obama administration announced the Homeowners Affordability and Stability Plan, an economic recovery plan to help home owners avoid foreclosure by refinancing mortgages in the wake of the Great Recession. The next day, CNBC business news editor Rick Santelli criticized the Plan in a live broadcast from the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. He said that those plans were "promoting bad behavior" by "subsidizing losers' mortgages". He suggested holding a tea party for traders to gather and dump the derivatives in the Chicago River on July 1. "President Obama, are you listening?" he asked.[116][117][118][119][120] A number of the floor traders around him cheered on his proposal, to the amusement of the hosts in the studio. Santelli's "rant" became a viral video after being featured on the Drudge Report.[121]

Beth McGrath of The New Yorker and Kate Zernike of The New York Times report that this where the Tea Party movement was first inspired to coalesce under the collective banner of "Tea Party".[107][116] Santelli's remarks "set the fuse to the modern anti-Obama Tea Party movement," according to journalist Lee Fang.[122] About 10 hours after Santelli's remarks, reTeaParty.com was bought to coordinate Tea Parties scheduled for Independence Day and, as of March 4, was reported to be receiving 11,000 visitors a day.[123] Within hours, the conservative political advocacy group Americans for Prosperity registered the domain name "TaxDayTeaParty.com", and launched a website calling for protests against Obama.[122] Overnight, websites such as "ChicagoTeaParty.com" (registered in August 2008 by Chicagoan Zack Christenson, radio producer for conservative talk show host Milt Rosenberg) were live within 12 hours.[123] By the next day, guests on Fox News had already begun to mention this new "Tea Party".[124] As reported by The Huffington Post, a Facebook page was developed on February 20 calling for Tea Party protests across the country.[125]

A "Nationwide Chicago Tea Party" protest was coordinated across more than 40 different cities for February 27, 2009, establishing the first national modern Tea Party protest.[126][127] The movement has been supported nationally by at least 12 prominent individuals and their associated organizations.[128] Fox News called many of the protests in 2009 "FNC Tax Day Tea Parties" which it promoted on air and sent speakers to.[129][130] This was to include then-host Glenn Beck, though Fox came to discourage him from attending later events.[131]

Health care bill

Opposition to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) has been consistent within the Tea Party movement.[11] The scheme has often been referred to as 'Obamacare' by critics, but was soon adopted as well by many of its advocates, including President Obama. This has been an aspect of an overall anti-government message throughout Tea Party rhetoric that includes opposition to gun control measures and to federal spending increases.[56]

Activism by Tea Party people against the major health-care reform law from 2009 to 2014 has, according to the Kansas City Star, focused on pushing for Congressional victories so that a repeal measure would pass both houses and that President Obama's veto could be overridden. Some conservative public officials and commentators such as columnist Ramesh Ponnuru have criticized these views as completely unrealistic with the chances of overriding a Presidential veto being slim, with Ponnuru stating that "If you have in 2017 a Republican government... and it doesn't get rid of Obamacare, then I think that is a huge political disaster".[56]

U.S. elections

Aside from rallies, some groups affiliated with the Tea Party movement began to focus on getting out the vote and ground game efforts on behalf of candidates supportive of their agenda starting in the 2010 elections.

In the 2010 midterm elections, The New York Times identified 138 candidates for Congress with significant Tea Party support, and reported that all of them were running as Republicans—of whom 129 were running for the House and 9 for the Senate.[132] A poll by The Wall Street Journal and NBC News in mid October showed 35% of likely voters were Tea-party supporters, and they favored the Republicans by 84% to 10%.[133] The first Tea Party affiliated candidate to be elected into office is believed to be Dean Murray, a Long Island businessman, who won a special election for a New York State Assembly seat in February 2010.[134]

According to statistics on an NBC blog, overall, 32% of the candidates that were backed by the Tea Party or identified themselves as Tea Party participants won election in 2010. Tea Party supported candidates won 5 of 10 Senate races (50%) contested, and 40 of 130 House races (31%) contested.[135] In the primaries for Colorado, Nevada and Delaware the Tea-party backed Senate Republican nominees defeated "establishment" Republicans that had been expected to win their respective Senate races, but went on to lose in the general election to their Democratic opponents.[136] The movement played a major role in the 2010 wave election[3][4] in which Republicans gained 63 House seats[5] and took control of the U.S. House of Representatives.[6]

The Tea Party is generally associated with the Republican Party.[137] Most politicians with the "Tea Party brand" have run as Republicans. In recent elections in the 2010s, Republican primaries have been the site of competitions between the more conservative, Tea Party wing of the party and the more moderate, establishment wing of the party. The Tea Party has incorporated various conservative internal factions of the Republican Party to become a major force within the party.[138][139]

Tea Party candidates were less successful in the 2012 election, winning four of 16 Senate races contested, and losing approximately 20% of the seats in the House that had been gained in 2010. Tea Party Caucus founder Michele Bachmann was re-elected to the House by a narrow margin.[140]

A May 2014 Kansas City Star article remarked about the Tea Party movement post-2012, "Tea party candidates are often inexperienced and sometimes underfunded. More traditional Republicans—hungry for a win—are emphasizing electability over philosophy, particularly after high-profile losses in 2012. Some in the GOP have made that strategy explicit."[56]

In June 2014, Tea Party favorite Dave Brat unseated the sitting GOP House Majority Leader Eric Cantor. Brat had previously been known as an economist and a professor at Randolph–Macon College, running a grassroots conservative campaign that espoused greater fiscal restraint and his Milton Friedman-based viewpoints.[141] Brat has since won the seat by a comfortable margin until losing his reelection in 2018.

In November 2014, Tim Scott became the first African-American member of the U.S. Senate from the South since the reconstruction era, winning the South Carolina seat formerly held by Jim DeMint in a special election.[142]

In the 2014 elections in Texas, the Tea Party made large gains, with numerous Tea Party favorites being elected into office, including Dan Patrick as Lieutenant Governor[143][144] and Ken Paxton as Attorney General,[143][145] in addition to numerous other candidates.[145]

In the 2015 Kentucky gubernatorial election, Matt Bevin, a Tea Party favorite who challenged Mitch McConnell in the Republican primary in the 2014 Kentucky Senate election,[146] won with over 52% of the vote, despite fears that he was too extreme for the state.[147][148][149] Bevin is the second Republican in 44 years to be Governor of Kentucky.[147]

IRS controversy

In May 2013, the Associated Press and The New York Times reported that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) flagged Tea Party groups and other conservative groups for review of their applications for tax-exempt status during the 2012 election. This led to both political and public condemnation of the agency, and triggered multiple investigations.[150]

Some groups were asked for donor lists, which is usually a violation of IRS policy. Groups were also asked for details about family members and about their postings on social networking sites. Lois Lerner, head of the IRS division that oversees tax-exempt groups, apologized on behalf of the IRS and stated, "That was wrong. That was absolutely incorrect, it was insensitive and it was inappropriate."[151][152] Testifying before Congress in March 2012, IRS Commissioner Douglas Shulman denied that the groups were being targeted based on their political views.[151][152]

Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah, the ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, rejected the apology as insufficient, demanding "ironclad guarantees from the I.R.S. that it will adopt significant protocols to ensure this kind of harassment of groups that have a constitutional right to express their own views never happens again."[152]

The resulting Senate subcommittee report ultimately found there had been "no bias", though Republican committeemembers filed a dissenting report.[153] According to the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, 18% of the conservative groups that had Tea Party or other related terms in their names flagged for extra scrutiny by the IRS had no evidence of political activity.[154] Michael Hiltzik, writing in the Los Angeles Times, stated that evidence put forth in the House report indicated the IRS had been struggling to apply complicated new rules to nonprofits that may have been involved in political activity, and had also flagged liberal-sounding groups.[155] Of all the groups flagged, the only one to lose tax exempt status was a group that trains Democratic women to run for office.[156]

After a two-year investigation, the Justice Department announced in October 2015 that "We found no evidence that any IRS official acted based on political, discriminatory, corrupt, or other inappropriate motives that would support a criminal prosecution."[157]

On October 25, 2017, the Trump Administration settled with a Consent Order for the case Linchpins of Liberty v. United States; the IRS consented to express "its sincere apology" for singling out the plaintiff for aggressive scrutiny, stating, "The IRS admits that its treatment of Plaintiffs during the tax-exempt determinations process, including screening their applications based on their names or policy positions, subjecting those applications to heightened scrutiny and inordinate delays, and demanding of some Plaintiffs' information that TIGTA determined was unnecessary to the agency's determination of their tax-exempt status, was wrong. For such treatment, the IRS expresses its sincere apology." That same month, the Treasury Department's inspector general reported that the I.R.S. had also targeted liberal groups, flagging organization names with terms that included "Progressive" and "Occupy".[158][159]

Role in the 2016 presidential election

The presidential candidate Donald Trump praised the Tea Party movement throughout his 2016 campaign.[160] In August 2015, he told a Tea Party gathering in Nashville that "The tea party people are incredible people. These are people who work hard and love the country and they get beat up all the time by the media."[160] In a January 2016 CNN poll at the beginning of the 2016 Republican primary, Trump led all Republican candidates modestly among self-identified Tea Party voters with 37 percent supporting Trump and 34 percent supporting Ted Cruz.[161]

Several commentators, including Jonathan Chait,[162] Jenny Beth Martin,[163][164] and Sarah Palin, argued that the Tea Party played a key role in the election of Donald Trump as the Republican Party presidential nominee, and eventually as U.S. president, and that Trump's election was even the culmination of the Tea Party and anti-establishment dissatisfaction associated with it. Martin stated after the election that "with the victory of Donald Trump, the values and principles that gave rise to the tea party movement in 2009 are finally gaining the top seat of power in the White House."[164]

On the other hand, other commentators, including Paul H. Jossey,[165] a conservative campaign finance attorney, and Jim Geraghty of the conservative National Review,[166] believed that the Tea Party to be dead or in decline. Jossey, for example, argued that the Tea Party "began as an organic, policy-driven grass-roots movement" but was ultimately "drained of its vitality and resources by national political action committees that dunned the movement's true believers endlessly for money to support its candidates and causes."[165]

Decline

This section needs to be updated. (June 2018) |

Tea Party activities began to decline in 2010.[167][168] According to Harvard professor Theda Skocpol, the number of Tea Party chapters across the country slipped from about 1,000 to 600 between 2009 and 2012, but that this is still "a very good survival rate." Mostly, Tea Party organizations are said to have shifted away from national demonstrations to local issues.[167] A shift in the operational approach used by the Tea Party has also affected the movement's visibility, with chapters placing more emphasis on the mechanics of policy and getting candidates elected rather than staging public events.[169][170]

The Tea Party's involvement in the 2012 GOP presidential primaries was minimal, owing to divisions over whom to endorse as well as lack of enthusiasm for all the candidates.[168] However, the 2012 GOP ticket did have an influence on the Tea Party: following the selection of Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney's vice-presidential running mate, The New York Times declared that the once fringe of the conservative coalition, Tea Party lawmakers are now "indisputably at the core of the modern Republican Party."[171]

Though the Tea Party has had a large influence on the Republican Party, it has attracted major criticism by public figures within the Republican coalition as well. Then-Speaker of the House John Boehner particularly condemned many Tea Party-connected politicians for their behavior during the 2013 U.S. debt ceiling crisis. "I think they're misleading their followers," Boehner was publicly quoted as saying, "They're pushing our members in places where they don't want to be, and frankly I just think that they've lost all credibility." In the words of The Kansas City Star, Boehner "stamped out Tea Party resistance to extending the debt ceiling... worried that his party's prospects would be damaged by adherence to the Tea Party's preference for default".[56]

One 2013 survey found that, in political terms, 20% of self-identified Republicans stated that they considered themselves as part of the Tea Party movement.[172] Tea Party participants rallied at the U.S. Capitol on February 27, 2014; their demonstrations celebrated the fifth anniversary of the movement coming together.[23]

By 2016, Politico noted that the Tea Party movement was essentially completely dead; however, the article noted that the movement seemed to die in part because some of its ideas had been absorbed by the mainstream Republican Party.[31] By 2019, it was reported that the conservative wing of the Republican Party "has basically shed the tea party moniker."[32]

Multiple sources identified remnants of the Tea Party movement as being among the participants of the January 6 United States Capitol attack in 2021.[173]

Dr. Geoffrey Kabaservice argued in 2020 that the Tea Party's

characteristic mistrust of norms was evident from the beginning in its embrace of birtherism, the racist conspiracy theory that claimed without evidence that Obama was secretly a foreign-born Muslim and ineligible for the presidency. Social media accelerated the spread of such conspiratorial beliefs, which further dissolved trust in established institutions and objective truth....the tea party never really died; its energies were reactivated with the presidential campaign of Donald Trump — who of course was the leading purveyor of birtherism.....both the tea party and Trump's movement also were rooted in fact-free conspiracy theories about the treachery of Democrats and elites, who allegedly plotted to destroy the livelihoods and traditions of "real Americans" for their own benefit.[174]

Composition

Demographics

Several polls have been conducted on the demographics of the movement. Though the various polls sometimes turn up slightly different results, they tend to show that Tea Party supporters tend more likely, than Americans overall, to be white, male, married, older than 45, regularly attending religious services, conservative, and to be more wealthy and have more education.[175][176][177][178][179] Broadly speaking, multiple surveys have found between 10% and 30% of Americans identified as members of the Tea Party movement.[23][180] Most Republicans and 20% of Democrats support the movement according to one Washington Post–ABC News poll.[181]

According to The Atlantic, the three main groups that provide guidance and organization for the protests, FreedomWorks, dontGO, and Americans for Prosperity, state that the demonstrations are an organic movement.[182] Conservative political strategist Tim Phillips, now head of Americans for Prosperity, has remarked that the Republican Party is "too disorganized and unsure of itself to pull this off".[183]

The Christian Science Monitor has reported that Tea Party activists "have been called neo-Klansmen and knuckle-dragging hillbillies", adding that "demonizing tea party activists tends to energize the Democrats' left-of-center base" and that "polls suggest that tea party activists are not only more mainstream than many critics suggest",[184] but that a majority of them are women, not angry white men.[184][185][186] The article quoted Juan Williams as saying that the Tea Party's opposition to health reform was based on self-interest rather than racism.[184]

A Gallup poll conducted in March 2010 found that—other than gender, income and politics—self-described Tea Party members were demographically similar to the population as a whole.[187] A 2014 article from Forbes.com stated that the Tea Party's membership appears reminiscent of the people who supported independent Ross Perot's presidential campaigns in the 1990s.[23]

When surveying supporters or participants of the Tea Party movement, polls have shown that they are to a very great extent more likely to be registered Republican, have a favorable opinion of the Republican Party and an unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party.[179][188][189] The Bloomberg National Poll of adults 18 and over showed that 40% of Tea Party supporters are 55 or older, compared with 32% of all poll respondents; 79% are white, 61% are men and 44% identify as "born-again Christians",[190] compared with 75%,[191] 48.5%,[192] and 34%[193] for the general population, respectively.

According to Susan Page and Naomi Jagoda of USA Today in 2010, the Tea Party was more "a frustrated state of mind" than "a classic political movement".[194] Tea party participants "are more likely to be married and a bit older than the nation as a whole".[194] They are predominantly white, but other groups make up just under one-fourth of their ranks.[194] They believe that the federal government has become too large and powerful.[194] Surveys of Republican primary voters in the South in 2012 show that Tea Party supporters were not driven by racial animosity. Instead there was a strong positive relationship with religious evangelicalism. Tea Party supporters were older, male, poorer, more ideologically conservative, and more partisan than their fellow Republicans.[195]

Each of those factors is associated among Republicans with being more racially conservative. Using multiple regression techniques and a very large sample of N=100,000 the authors hold all the background factors statistically constant. When that happens, the tea party Republicans and other Republicans are practically identical on racial issues.[196] In contrast, a 2015 study found that racial resentment was one of the strongest predictors for Tea Party Movement membership.[197]

Polling of supporters

An October 2010 Washington Post canvass of local Tea Party organizers found 99% said "concern about the economy" was an "important factor".[74] Various polls have also probed Tea Party supporters for their views on a variety of political and controversial issues. On the question of whether they think their own income taxes this year are fair, 52% of Tea Party supporters told pollsters for CBS/New York Times that they were, versus 62% in the general population (including Tea Party supporters).[188] A Bloomberg News poll found that Tea Partiers are not against increased government action in all cases. "The ideas that find nearly universal agreement among Tea Party supporters are rather vague," says J. Ann Selzer, the pollster who created the survey. "You would think any idea that involves more government action would be anathema, and that is just not the case."

In advance of a new edition of their book American Grace, political scientists David E. Campbell of Notre Dame and Robert D. Putnam of Harvard published in a New York Times opinion the results of their research into the political attitudes and background of Tea Party supporters. Using a pre-Tea Party poll in 2006 and going back to the same respondents in 2011, they found the supporters to be not "nonpartisan political neophytes" as often described, but largely "overwhelmingly partisan Republicans" who were politically active prior to the Tea Party. The survey found Tea Party supporters "no more likely than anyone else" to have suffered hardship during the 2007–2010 recession. Additionally, the respondents were more concerned about "putting God in government" than with trying to shrink government.[198][199]

The 2010 midterm elections demonstrated considerable skepticism within the Tea Party movement with respect to the dangers and the reality of global warming. A New York Times/CBS News Poll during the election revealed that only a small percentage of Tea Party supporters considered global warming a serious problem, much less than the portion of the general public that does. The Tea Party is strongly opposed to government-imposed limits on carbon dioxide emissions as part of emissions trading legislation to encourage use of fuels that emit less carbon dioxide.[200] An example is the movement's support of California Proposition 23, which would suspend AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006.[201] The proposition failed to pass, with less than 40% voting in favor.[202]

Many[quantify] of the movement's participants favored stricter measures against illegal immigration.[203]

Polls found that just 7% of Tea Party supporters approve of how Obama is doing his job compared to 50% (as of April 2010) of the general public,[188][needs update] and that roughly 77% of supporters had voted for Obama's Republican opponent, John McCain in 2008.[178][179]

A University of Washington poll of 1,695 registered voters in the state of Washington reported that 73% of Tea Party supporters disapprove of Obama's policy of engaging with Muslim countries, 88% approve of the controversial Arizona immigration law enacted in 2010 that requires police to question people they suspect are illegal immigrants for proof of legal status, 54% feel that immigration is changing the culture in the U.S. for the worse, 82% do not believe that gay and lesbian couples should have the legal right to marry, and that about 52% believe that "[c]ompared to the size of the group, lesbians and gays have too much political power".[204][205][206]

Leadership

The movement has been supported nationally by prominent individuals and organizations.[207][208]

Individuals

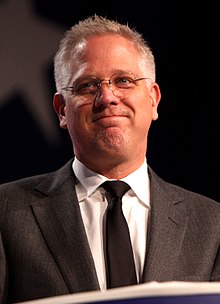

An October 2010 Washington Post canvass of 647 local Tea Party organizers asked "which national figure best represents your groups?" and got the following responses: no one 34%, Sarah Palin 14%, Glenn Beck 7%, Jim DeMint 6%, Ron Paul 6%, Michele Bachmann 4%.[74]

The success of candidates popular within the Tea Party movement has boosted Palin's visibility.[209] Rasmussen and Schoen (2010) conclude that "She is the symbolic leader of the movement, and more than anyone else has helped to shape it."[210]

In June 2008, Congressman Ron Paul announced his non-profit organization called Campaign for Liberty as a way of continuing the grassroots support involved in Ron Paul's 2007–2008 presidential run.[citation needed] This announcement corresponded with the suspension of his campaign.[citation needed]

In July 2010, Bachmann formed the House congressional Tea Party Caucus. This congressional caucus, which Bachmann chaired, is devoted to the Tea Party's stated principles of "fiscal responsibility, adherence to the Constitution, and limited government".[211] As of March 31, 2011, the caucus consisted of 62 Republican representatives.[76] Rep. Jason Chaffetz and Melissa Clouthier have accused them of trying to hijack or co-opt the grassroots Tea Party Movement.[212]

Organizations

Note: the self-reported membership numbers below are several years old.

- Tea Party Patriots, an organization with more than 1,000 affiliated groups across the nation[213] that proclaims itself to be the "Official Home of the Tea Party Movement".[214]

- Americans for Prosperity, an organization founded by David H. Koch in 2003, and led by Tim Phillips. The group has over 1 million members in 500 local affiliates and led protests against health care reform in 2009.[207]

- FreedomWorks, an organization led by Matt Kibbe. The group has over 1 million members in 500 local affiliates. It makes local and national candidate endorsements.[207]

- Tea Party Express, a national bus tour run by Our Country Deserves Better PAC, itself a conservative political action committee created by Sacramento-based Republican consulting firm Russo, Marsh, and Associates.[215][216][217]

FreedomWorks, Americans for Prosperity, and DontGo, a free market political activist non-profit group, were guiding the Tea Party movement in April 2009, according to The Atlantic.[182] Americans for Prosperity and FreedomWorks were "probably the leading partners" in the September 2009 Taxpayer March on Washington, also known as the 9/12 Tea Party, according to The Guardian.[91]

- Tea Party Review

In 2011 the movement launched a monthly magazine, the Tea Party Review.[218]

- For-profit businesses

- Tea Party Nation, which sponsored the National Tea Party Convention that was criticized for its $549 ticket price[219][220][221][222] and because Palin was apparently paid $100,000 for her appearance (which she put towards SarahPAC[223]).[224]

- Informal organizations and coalitions

- The National Tea Party Federation, formed on April 8, 2010, by several leaders in the Tea Party movement to help spread its message and to respond to critics with a quick, unified response.[225]

- The Nationwide Tea Party Coalition, a loose national coalition of several dozen local tea party groups.[226]

- Student movement

- Tea Party Students organized the 1st National Tea Party Students Conference, which was hosted by Tea Party Patriots at its American Policy Summit in Phoenix on February 25–27, 2011. The conference included sessions with Campus Reform, Students For Liberty, Young America's Foundation, and Young Americans for Liberty.[227]

Other influential organizations include Americans for Limited Government, the training organization American Majority, the Our Country Deserves Better political action committee, and Glenn Beck's 9-12 Project, according to the National Journal in February 2010.[208]

Fundraising

Sarah Palin headlined four "Liberty at the Ballot Box" bus tours, to raise money for candidates and the Tea Party Express. One of the tours visited 30 towns and covered 3,000 miles.[228] Following the formation of the Tea Party Caucus, Michele Bachmann raised $10 million for a political action committee, MichelePAC, and sent funds to the campaigns of Sharron Angle, Christine O'Donnell, Rand Paul, and Marco Rubio.[229] In September 2010, the Tea Party Patriots announced it had received a $1,000,000 donation from an anonymous donor.[230]

Support of Koch brothers

In an August 30, 2010, article in The New Yorker, Jane Mayer asserted that the brothers David H. Koch and Charles G. Koch and Koch Industries provided financial support to one of the organizations that became part of the Tea Party movement through Americans for Prosperity.[231][232] The AFP's "Hot Air Tour" was organized to fight against taxes on carbon use and the activation of a cap and trade program.[233] A Koch Industries company spokesperson issued a 2010 statement saying "No funding has been provided by Koch companies, the Koch foundation, or Charles Koch or David Koch specifically to support the tea parties".[234]

Public opinion

2010 polling

A USA Today/Gallup poll conducted in March 2010 found that 28% of those surveyed considered themselves supporters of the Tea Party movement, 26% opponents, and 46% neither.[235] These figures remained stable through January 2011, but public opinion changed by August 2011. In a USA Today/Gallup poll conducted in January 2011, approximately 70% of adults, including approximately 9 out of 10 Republicans, felt Republican leaders in Congress should give consideration to Tea Party movement ideas.[236] In August 2011, 42% of registered voters, but only 12% of Republicans, said Tea Party endorsement would be a "negative" and that they would be "less likely" to vote for such a candidate.[237]

A Gallup Poll in April 2010 found 47% of Americans had an unfavorable image of the Tea Party movement, as opposed to 33% who had a favorable opinion.[238] A 2011 opinion survey by political scientists David E. Campbell and Robert D. Putnam found the Tea Party ranked at the bottom of a list of "two dozen" American "religious, political, and racial groups" in terms of favorability—"even less liked than Muslims and atheists."[199][239] In November 2011, The New York Times cited opinion polls showing that support for the Tea Party had "fallen sharply even in places considered Tea Party strongholds." It quoted pollster Andrew Kohut speculating that the Tea Party position in Congress was perceived as "too extreme and not willing to compromise".[240]

A CBS News/New York Times poll in September 2010 showed 19% of respondents supported the movement, 63% did not, and 16% said they did not know. In the same poll, 29% had an unfavorable view of the Tea Party, compared to 23% with a favorable view.[241] The same poll retaken in August 2011 found that 20% of respondents had a favorable view of the Tea Party and 40% had an unfavorable view.[242] A CNN/ORC poll taken September 23–25, 2011 found that the favorable/unfavorable ratio was 28% versus 53%.[243]

An NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll in September 2010 found 27% considered themselves Tea Party supporters. 42% said the Tea Party has been good for the U.S. political system; 18% called it a bad thing. Those with an unfavorable view of the Tea Party outnumbered those with a favorable view 36–30%. In comparison, the Democratic Party was viewed unfavorably by a 42–37% margin, and the Republican Party by 43–31%.[244]

A poll conducted by the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute in March 2010 found that 13% of national adults identified themselves as part of the Tea Party movement but that the Tea Party had a positive opinion by a 28–23% margin with 49% who did not know enough about the group to form an opinion.[179] A similar poll conducted by the Winston Group in April 2010 found that 17% of American registered voters considered themselves part of the Tea Party movement.[189]

After debt-ceiling crisis

After the mid-2011 debt ceiling crisis, polls became more unfavorable to the Tea Party.[245][246] According to a Gallup poll, 28% of adults disapproved of the Tea Party compared to 25% approving, and noted that "[t]he national Tea Party movement appears to have lost some ground in popular support after the blistering debate over raising the nation's debt ceiling in which Tea Party Republicans... fought any compromise on taxes and spending".[245] Similarly, a Pew poll found that 29% of respondents thought Congressional Tea Party supporters had a negative effect compared to 22% thinking it was a positive effect. It noted that "[t]he new poll also finds that those who followed the debt ceiling debate very closely have more negative views about the impact of the Tea Party than those who followed the issue less closely."[246] A CNN/ORC poll put disapproval at 51% with a 31% approval.[247]

2012 polling

A Rasmussen Reports poll conducted in April 2012 showed 44% of likely U.S. voters held at least a somewhat favorable view of Tea Party activists, while 49% share an unfavorable opinion of them. When asked if the Tea Party movement would help or hurt Republicans in the 2012 elections, 53% of Republicans said they see the Tea Party as a political plus.[248]

2013 and 2014 polling

A February 2014 article from Forbes.com reported about the past few years, "Nationally, there is no question that negative views of the Tea Party have risen. But core support seems to be holding steady."[23] In October 2013, Rasmussen Reports research found as many respondents (42%) identify with the Tea Party as with President Obama. However, while 30% of those polled viewed the movement favorably, 50% were unfavorable; in addition, 34% considered the movement a force for good while 43% considered them bad for the nation. On major national issues, 77% of Democrats said their views were closest to Obama's; in contrast, 76% of Republicans and 51% of unaffiliated voters identified closely with the Tea Party.[249]

Other survey data over recent years show that past trends of partisan divides about the Tea Party remain. For example, a Pew Research Center poll from October 2013 reported that 69% of Democrats had an unfavorable view of the movement, in contrast to 49% of independents and 27% of Republicans.[23] A CNN/ORC poll also conducted October 2013 generally showed that 28% of Americans were favorable to the Tea party while 56% were unfavorable.[250] In an AP/GfK survey from January 2014, 27% of respondents stated that they considered themselves a Tea Party supporter in comparison to 67% that said that they did not.[23]

Symbols

Beginning in 2009, the Gadsden flag became widely used as a symbol by Tea Party protesters nationwide.[251][252] It was also displayed by members of Congress at Tea Party rallies.[253] Some lawmakers dubbed it a political symbol due to the Tea Party connection[252] and the political nature of Tea Party supporters.[254]

The Second Revolution flag gained national attention on January 19, 2010.[255] It is a version of the Betsy Ross flag with a Roman numeral "II" in the center of the circle of 13 stars symbolizing a second revolution in America.[256] The Second Revolution flag has been called synonymous with Tea Party causes and events.[257]

"Teabagger"

Some participants of the movement adopted the term as a verb, and a few others referred to themselves as "teabaggers".[258][259] News media and progressive commentators outside the movement began to use the term mockingly and derisively, alluding to the sexual connotation of the term when referring to Tea Party protesters. The first pejorative use of the term was in 2007 by Indiana Democratic Party Communications Director Jennifer Wagner.[260] The use of the double entendre evolved from Tea Party protest sites encouraging readers to "Tea bag the fools in DC" to the political left adopting the term for derogatory jokes.[259][261][262] It has been used by several media outlets to humorously refer to Tea Party-affiliated protestors.[263] Some conservatives have advocated that the non-vulgar meaning of the word be reclaimed.[259] Grant Barrett, co-host of the A Way with Words radio program, has listed teabagger as a 2009 buzzword meaning, "a derogatory name for attendees of Tea Parties, probably coined in allusion to a sexual practice".[264]

Commentary by the Obama administration

On April 29, 2009, Obama commented on the Tea Party protests during a townhall meeting in Arnold, Missouri: "Let me just remind them that I am happy to have a serious conversation about how we are going to cut our health care costs down over the long term, how we're going to stabilize Social Security. Claire McCaskill and I are working diligently to do basically a thorough audit of federal spending. But let's not play games and pretend that the reason is because of the recovery act, because that's just a fraction of the overall problem that we've got. We are going to have to tighten our belts, but we're going to have to do it in an intelligent way. And we've got to make sure that the people who are helped are working American families, and we're not suddenly saying that the way to do this is to eliminate programs that help ordinary people and give more tax cuts to the wealthy. We tried that formula for eight years. It did not work. And I don't intend to go back to it."[265][266]

On April 15, 2010, Obama noted the passage of 25 different tax cuts over the past year, including tax cuts for 95% of working Americans. He then remarked, "So I've been a little amused over the last couple of days where people have been having these rallies about taxes. You would think they would be saying thank you. That's what you'd think."[267][268]

On September 20, 2010, at a townhall discussion sponsored by CNBC, Obama said healthy skepticism about government and spending was good, but it was not enough to just say "Get control of spending", and he challenged the Tea Party movement to get specific about how they would cut government debt and spending: "And so the challenge, I think, for the Tea Party movement is to identify specifically what would you do. It's not enough just to say, get control of spending. I think it's important for you to say, I'm willing to cut veterans' benefits, or I'm willing to cut Medicare or Social Security benefits, or I'm willing to see these taxes go up. What you can't do—which is what I've been hearing a lot from the other side—is say we're going to control government spending, we're going to propose $4 trillion of additional tax cuts, and that magically somehow things are going to work."[269][270]

Media coverage

U.S. News & World Report reported that the nature of the coverage of the protests has become part of the story.[271] On CNN's Situation Room, journalist Howard Kurtz commented that "much of the media seems to have chosen sides". He says that Fox News portrayed the protests "as a big story, CNN as a modest story, and MSNBC as a great story to make fun of. And for most major newspapers, it's a nonstory".[271] There were reports that the movement had been actively promoted by the Fox News Channel.[272][273]

According to Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, a progressive media watchdog, there is a disparity between large coverage of the Tea Party movement and minimal coverage of larger movements. In 2009, the major Tea Party protests were quoted twice as often as the National Equality March despite a much lower turnout.[274] In 2010, a Tea Party protest was covered 59 times as much as the US Social Forum (177 Tea Party mentions versus 3 for Social Forum) despite the attendance of the latter being 25 times as much (600 Tea Party attendees versus at least 15,000 for Social Forum).[275]

In April 2010, responding to a question from the media watchdog group Media Matters posed the previous week, Rupert Murdoch, the chief executive of News Corporation, which owns Fox News, said, "I don't think we should be supporting the Tea Party or any other party." That same week, Fox News canceled an appearance by Sean Hannity at a Cincinnati Tea Party rally.[276]

Following the September 12 Taxpayer March on Washington, Fox News said it was the only cable news outlet to cover the emerging protests and took out full-page ads in The Washington Post, the New York Post, and The Wall Street Journal with a prominent headline reading, "How did ABC, CBS, NBC, MSNBC, and CNN miss this story?"[277] CNN news anchor Rick Sanchez disputed Fox's assertion, pointing to various coverage of the event.[278][279][280] CNN, NBC, CBS, MSNBC, and CBS Radio News provided various forms of live coverage of the rally in Washington throughout the day on Saturday, including the lead story on CBS Evening News.[278][280][281][282]

James Rainey of the Los Angeles Times said that MSNBC's attacks on the tea parties paled compared to Fox's support, but that MSNBC personalities Keith Olbermann, Rachel Maddow and Chris Matthews were hardly subtle in disparaging the movement.[283] Howard Kurtz has said that, "These [FOX] hosts said little or nothing about the huge deficits run up by President Bush, but Barack Obama's budget and tax plans have driven them to tea. On the other hand, CNN and MSNBC may have dropped the ball by all but ignoring the protests."[284]

In the January/February 2012 issue of Foreign Affairs, Francis Fukuyama stated that the Tea Party is supporting "politicians who serve the interests of precisely those financiers and corporate elites they claim to despise" and inequality while comparing and contrasting it with the occupy movement.[285][286]

Tea Party's views of media coverage

In October 2010, a survey conducted by The Washington Post found that the majority of local Tea Party organizers consider the media coverage of their groups to be fair. Seventy-six percent of the local organizers said media coverage has been fair, while 23 percent have said coverage was unfair. This was based on responses from all 647 local Tea Party organizers the Post was able to contact and verify, from a list of more than 1,400 possible groups identified.[287]

Perceptions of the Tea Party

The movement has been called a mixture of conservative,[19] libertarian,[17] and populist[18] activists. As stated before, opinions in terms of the U.S. major political parties play a large role in terms of attitudes about the Tea Party movement, with one study finding that 20% of self-identified Republicans personally view themselves as part of the Tea Party.[172]

The movement has sponsored protests and supported political candidates circa 2009.[20][21][22] Since the movement's inception, in the late 2000s, left wing groups have accused the party of racism and intolerance.[288][289] Left leaning opponents have cited various incidents as evidence that the movement is, in their opinion, propelled by various forms of bigotry.[288][289] Supporters say the incidents are isolated acts attributable to a small fringe that is not representative of the movement.[288][289] Accusations that the news media are biased either for or against the movement are common, while polls and surveys have been faced with issues regarding the population surveyed, and the meaningfulness of poll results from disparate groups.[290]

Although the Tea Party has a libertarian element in terms of some issue convictions, most American libertarians do not support the movement enough to identify with it. A 2013 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) found that 61% of identified libertarians stated they did not consider themselves part of the tea party. This split exists due to the strong Christian right influence in the movement, which puts the majority of the tea party movement at direct odds against libertarians on issues such as the war on drugs (with the aforementioned survey finding that 71% of libertarians support legalizing marijuana).[172] Some libertarian leaning supporters have grown increasingly annoyed by the influx of religious social issues into the movement. Many in the movement would prefer the complex social issues such as homosexuality, abortion, and religion to be left out of the discussion, while instead increasing the focus on limited government and states' rights.[citation needed]

According to a review in Publishers Weekly published in 2012, professor Ronald P. Formisano in The Tea Party: A Brief History provides an "even-handed perspective on and clarifying misconceptions about America's recent political phenomenon" since "party supporters are not isolated zealots, and may, like other Americans, only want to gain control over their destinies". Professor Formisano sees underlying social roots and draws a parallel between the tea party movement and past support for independent candidate Ross Perot,[291] a similar point to that made in Forbes as mentioned earlier.[23]

Controversies

The final round of debate before voting on the health care bill was marked with vandalism and widespread threats of violence to at least ten Democratic lawmakers across the country, which created public relations problems for the fledgeling Tea Party movement. On March 22, 2010, in what the New York Times called "potentially the most dangerous of many acts of violence and threats against supporters of the bill," a Lynchburg, Virginia Tea Party organizer and the Danville, Virginia Tea Party Chairman both posted the home address of Representative Tom Perriello's brother (mistakenly believing it was the Congressman's address) on their websites, and encouraged readers to "drop by" to express their anger against Representative Perriello's vote in favor of the healthcare bill. The following day, after smelling gas in his house, a severed gas line that connected to a propane tank was discovered on Perriello's brother's screened-in porch. Local police and FBI investigators determined that it was intentionally cut as an act of vandalism. Perriello's brother also received a threatening letter referencing the legislation. Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli stated that posting a home address on a website and encouraging people to visit is "an appalling approach. It's not civil discourse, it's an invitation to intimidation and it's totally unacceptable." Leaders of the Tea Party movement tried to contain the public relations damage by denouncing the violent acts and distancing themselves from those behind the acts. One Tea Party website issued a response saying the Tea Party member's action of posting the address "was not requested, sanctioned or endorsed by the Lynchburg Tea Party". The director of the Northern Colorado Tea Party said, "Although many are frustrated by the passage of such controversial legislation, threats are absolutely not acceptable in any form, to any lawmaker, of any party."[292]

In early July 2010, the North Iowa Tea Party (NITP) posted a billboard showing a photo of Adolf Hitler with the heading "National Socialism", one of Barack Obama with the heading "Democrat Socialism", and one of Vladimir Lenin with the heading "Marxist Socialism", all three marked with the word "change" and the statement "Radical leaders prey on the fearful and naive". It received sharp criticism, including some from other Tea Party activists. NITP co-founder Bob Johnson acknowledged the anti-socialist message may have gotten lost amid the fascist and communist images. Following a request from the NITP, the billboard was removed on July 14.[293]

See also

- Coffee Party USA, a progressive alternative to the Tea Party started in 2010, opposing corporate personhood rather than taxes

- Conservatism in the United States

- Donald Trump presidential campaign, 2016

- Election denial movement in the United States

- Indivisible movement, a progressive alternative to the Tea Party started in 2016

- Radical right

- United Kingdom Independence Party, third largest political party in the U.K. by popular vote in 2015, considered by some people as the British version of the Tea Party.[294]

References

- ^ "Tea Party Protesters March on Washington". ABC News. September 12, 2009.

- ^ "GOP breaks may stem from party resistance to all things Obama". PBS NewsHour. March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Blake, Aaron (February 1, 2016). "The GOP's 'tea party' Class of 2010 is heading for the exits -- fast/". Washington Post.

- ^ a b Akin, Stephanie (September 26, 2018). "Tea Party Pioneer Says Democrats Can't Match That Wave". Roll Call.

- ^ a b Peoples, Steve (December 8, 2010). "Final House Race Decided; GOP Net Gain: 63 Seats". Roll Call.

- ^ a b Harris, Paul; MacAskill, Ewen (November 3, 2010). "US midterm election results herald new political era as Republicans take House". The Guardian.

- ^ Gallup: Tea Party's top concerns are debt, size of government The Hill, July 5, 2010

- ^ Somashekhar, Sandhya (September 12, 2010). Tea Party DC March: "Tea party activists march on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Good, Chris (October 6, 2010). "On Social Issues, Tea Partiers Are Not Libertarians". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (November 15, 2010). "Tea party groups push GOP to quit culture wars, focus on deficit". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c McMorris-Santoro, Evan (April 5, 2010). "The Town Hall Dog That Didn't Bite". Talking Points Memo. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Roy, Avik. April 7, 2012. The Tea Party's Plan for Replacing Obamacare. Forbes. Retrieved: March 6, 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Tom (February 27, 2014). "5 years later, here's how the tea party changed politics". CNN.

- ^ Somin, Ilya (May 26, 2011). "The Tea Party Movement and Popular Constitutionalism". Northwestern University Law Review. Rochester, NY. SSRN 1853645.

- ^ Monbiot, George (October 25, 2010). "The Tea Party movement: deluded and inspired by billionaires". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ Nesbit, Jeff (April 5, 2016). "The Secret Origins of the Tea Party". Time.

- ^ a b Ekins, Emily (September 26, 2011). "Is Half the Tea Party Libertarian?". Reason. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

Kirby, David; Ekins, Emily McClintock (August 6, 2012). "Libertarian Roots of the Tea Party". Cato. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019.{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Halloran, Liz (February 5, 2010). "What's Behind The New Populism?". NPR. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Barstow, David (February 16, 2010). "Tea Party Lights Fuse for Rebellion on Right". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Fineman, Howard (April 6, 2010). "Party Time". Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2019. - ^ a b Pauline Arrillaga (April 14, 2014). "Tea Party 2012: A Look At The Conservative Movement's Last Three Years". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Michelle Boorstein (October 5, 2010). "Tea party, religious right often overlap, poll shows". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Peter Wallsten; Danny Yadron (September 29, 2010). "Tea-Party Movement Gathers Strength". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019. - ^ a b Servatius, David (March 6, 2009). "Anti-tax-and-spend group throws "tea party" at Capitol". Deseret News. Archived from the original on June 13, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ a b "Anger Management". The Economist. March 5, 2009. Archived from the original on May 10, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Tapscott, Mark (March 19, 2009). "Tea parties are flash crowds Obama should fear". The San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bowman, Karlyn; Marsico, Jennifer (February 24, 2014). "As The Tea Party Turns Five, It Looks A Lot Like The Conservative Base". Forbes.com. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Boston Tea Party Is Protest Template". UPI. April 20, 2008.

- ^ Etheridge, Eric (February 20, 2009). "Rick Santelli: Tea Party Time". New York Times: Opinionator.

- ^ Pallasch, Abdon M. (September 19, 2010). "'Best 5 minutes of my life'; His '09 CNBC rant against mortgage bailouts for 'losers' ignited the Tea Party movement". Chicago Sun-Times. p. A4.

- ^ "Tea Party: Palin's Pet, Or Is There More To It Underneath". April 15, 2014. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014.

- ^ "Founding Mothers and Fathers of the Tea Party Movement," by Michael Patrick Leahy Archived January 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Ragusa, Jordan; Gaspar, Anthony (2016). "Where's the Tea Party? An Examination of the Tea Party's Voting Behavior in the House of Representatives". Political Research Quarterly. 69 (2): 361–372. doi:10.1177/1065912916640901. S2CID 156591086.

- ^ "Americans for Prosperity". FactCheck.org. June 16, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "How We Killed the Tea Party". Politico. August 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Belvedere, Matthew J. (March 15, 2019). "'It's their turn' – former GOP House Speaker John Boehner says Democrats are having their own tea party-like moment". CNBC.

- ^ "Economic Freedom". teapartypatriots.org. Tea Party Patriots. June 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Price Foley, Elizabeth (Spring 2011). "Sovereignty, Rebalanced: The Tea Party and Constitutional Amendments". Tennessee Law Review. 78 (3): 751–64. SSRN 1904656.

- Elizabeth Price Foley, law professor at Florida International University College of Law, writing on the Tea Party's proclamations regarding the Constitution, observed: "Tea Party opposition to bailouts, stimulus packages and health-care reform is reflected in various proposals to amend the Constitution, including proposals to require a balanced budget, repeal the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Amendments, and give states a veto power over federal laws (the so-called Repeal Amendment)."

- ^ Zernike, Kate (2010). Boiling Mad: Inside Tea Party America. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 65–66. ISBN 9781429982726.

- Kate Zernike, a national correspondent for The New York Times, wrote: "It could be hard to define a Tea Party agenda; to some extent it depended on where you were. In the Northeast, groups mobilized against high taxes; in the Southwest, illegal immigration. Some Tea Partiers were clearer about what they didn't want than what they did. But the shared ideology—whether for young libertarians who came to the movement through Ron Paul or older 9/12ers who came to it through Glenn Beck—was the belief that a strict interpretation of the Constitution was the solution to government grown wild. [...] By getting back to what the founders intended, they believed they could right what was wrong with the country. Where in the Constitution, they asked, does it say that the federal government was supposed to run banks? Or car companies? Where does it say that people have to purchase health insurance? Was it so much to ask that officials honor the document they swear an oath to uphold?"

- ^ Staff writer (July 5, 2013). "Tea Party groups ramp up fight against immigration bill, as August recess looms". Fox News.

- ^ Woodruff, Betsy (June 20, 2013). "Tea Party – vs – Immigration Reform". National Review.

- ^ a b Gabriel, Trip (December 25, 2012). "Clout Diminished, Tea Party Turns to Narrower Issues". The New York Times.

- ^ Rauch, Jonathan (March 2, 2011). "The Tea Party's Next Move". National Journal. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013.

- ^ Carey, Nick (October 15, 2012). "Tea Party versus Agenda 21: Saving the U.S. or just irking it?". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Ballhaus, Rebecca (June 19, 2013). "Tea Party Protesters Rally Against IRS, Government". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b c Rauch, Jonathan (March 2, 2011). "Group Think: Inside the Tea Party's Collective Brain". National Journal.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Christopher W. (Fall 2011). "The Tea Party and the Constitution" (PDF). Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly. 39 (1): 193–252. SSRN 2218595. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2015. Also available via heinonline.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (March 13, 2010). "Tea-ing Up the Constitution". New York Times.

- ^ Somin, Ilya (2011). "The Tea Party Movement and Popular Constitutionalism". Northwestern University Law Review Colloquy. Pdf.

- ^ Zietlow, Rebecca E. (April 2012). "Popular Originalism? The Tea Party Movement and Constitutional Theory". Florida Law Review. 64 (2): 483–512. Pdf.

- Rebecca E. Zietlow, law professor at the University of Toledo College of Law, characterizes the Tea Party's constitutional position as a combination of two schools of thought: "originalism" and "popular constitutionalism."

- "Tea Party activists have invoked the Constitution as the foundation of their conservative political philosophy. These activists are engaged in 'popular originalism,' using popular constitutionalism—constitutional interpretation outside of the courts—to invoke originalism as interpretive method."

- Rebecca E. Zietlow, law professor at the University of Toledo College of Law, characterizes the Tea Party's constitutional position as a combination of two schools of thought: "originalism" and "popular constitutionalism."

- ^ a b Skocpol, Theda; Williamson, Vanessa (2012). The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. Oxford University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-19-983263-7.

- ^ Zernike, Kate (2010). Boiling Mad: Inside Tea Party America. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-1429982726.

- ^ See also:

- Perrin, Andrew J.; Tepper, Stephen J.; Caren, Neal; Morris, Sally (May 2011). "Cultures of the Tea Party". Contexts. 10 (2): 74–75. doi:10.1177/1536504211408945.

- Ryan, James E. (November 2011). "Laying Claim to the Constitution: The Promise of New Textualism". Virginia Law Review. 97 (7): 1549–1550. JSTOR 41307888.

- Formisano, Ronald (2012). The Tea Party: A Brief History. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 52.

- ^ a b Associated Press (January 28, 2010). "Tea Partiers shaking up races across country". KTVB News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Zernike, Kate (March 12, 2010). "Tea Party Avoids Divisive Social Issues". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (November 15, 2010). "Tea party groups push GOP to quit culture wars, focus on deficit". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Schumacher Cohen, Julie (April 19, 2012). "The Role of Religion (or Not) in the Tea Party Movement: Current Debates & The Anti-Federalists". Concept (student magazine). Vol. 35. Villanova University. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Teddy (February 9, 2010). "Tea Party Activists Craft 'Contract from America'". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Davis, Teddy (April 15, 2010). "Tea Party Activists Unveil 'Contract from America'". ABC News. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Helling, Dave (May 17, 2014). "Tea party says it is winning the message war despite losing election battles". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ Mead, Walter Russell (March–April 2011). "The Tea Party and American Foreign Policy: What Populism Means for Globalism". Foreign Affairs. pp. 28–44.

- ^ "H.Con.Res. 51: Directing the President, pursuant to section 5(c) of the War ... (On the Resolution)". GovTrack.us. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ "S. 3576: A bill to provide limitations on United States assistance, and ... (On Passage of the Bill)". GovTrack.us. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ McLaughlin, Seth (September 10, 2013). "Tea party-linked lawmakers shun strike on Syria". Washington Times.

- ^ Pecquet, Julian (August 31, 2013). "Tea Party takes lead on Syria". The Hill. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Formisano 2012, p. 8