Names of the American Civil War

The most common name for the American Civil War in modern American usage is simply "The Civil War". Although rarely used during the war, the term "War Between the States" became widespread afterward in the Southern United States. During and immediately after the war, Northern historians often used the terms "War of the Rebellion" and "Great Rebellion", and the Confederate term was "War for Southern Independence", which regained some currency in the 20th century but has again fallen out of use. The name "Slaveholders' Rebellion" was used by Frederick Douglass and appears in newspaper articles. "Freedom War" is used to celebrate the war's effect of ending slavery.

During the Jim Crow era of the 1950s, the term "War of Northern Aggression" developed under the Lost Cause of the Confederacy movement by Southern historical revisionists or negationists. This label was coined by segregationists in an effort to equate contemporary efforts to end segregation with 19th-century efforts to abolish slavery.

Several names also exist for the forces on each side; the opposing forces named battles differently as well. The Union forces frequently named battles for bodies of water that were prominent on or near the battlefield, but Confederates most often used the name of the nearest town. As a result, many battles have two or more names that have had varying use, but with some notable exceptions, one name has eventually tended to take precedence. Commentators sometimes explain the naming scheme as linked to the economic and demographic differences between North and South – to the more industrialised North natural features like creeks would be notable whereas the more rural and agrarian Southerners would consider towns more remarkable. In truth both North and South were far less urbanised than modern societies and most Americans North and South did not live in cities and most of the workforce were agricultural laborers of some sort.

Enduring names

[edit]Civil War

[edit]In the United States, "Civil War" is the most common term for the conflict and has been used by the overwhelming majority of reference books, scholarly journals, dictionaries, encyclopedias, popular histories, and mass media in the United States since the early 20th century.[1] The National Park Service, the government organization entrusted by the US Congress to preserve the battlefields of the war, uses this term.[2][full citation needed] Writings of prominent men such as Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee,[3][full citation needed] Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, P. G. T. Beauregard, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and Judah P. Benjamin used the term "Civil War" during the conflict.[citation needed] Abraham Lincoln used it on multiple occasions.[4][5][6]

English-language historians[7][8][9] outside the United States usually refer to the conflict as the "American Civil War". Such variations are also used in the United States if the war might otherwise be confused with another civil war such as the English Civil War of the 17th century, the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922, or the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939.

War Between the States

[edit]

The term "War Between the States" was rarely used during the war but became prevalent afterward among proponents of the "Lost Cause" interpretation of the war.[10]

The Confederate government avoided the term "civil war", which assumes both combatants to be part of a single country, and so referred to it in official documents as the "War between the Confederate States of America and the United States of America".[11] European diplomacy produced a similar formula for avoiding the phrase "civil war". Queen Victoria's proclamation of British neutrality referred to "hostilities ... between the Government of the United States of America and certain States styling themselves the Confederate States of America".[11]

After the war, the memoirs of former Confederate officials and veterans (Joseph E. Johnston, Raphael Semmes, and especially Alexander Stephens) commonly used the term "War Between the States". In 1898, the United Confederate Veterans formally endorsed the name. In the early 20th century, the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) led a campaign to promote the term "War Between the States" in the media and public schools. UDC efforts to convince the US Congress to adopt the term began in 1913 but were unsuccessful. Congress has never adopted an official name for the war. The name "War Between the States" is inscribed on the USMC War Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. The name was personally ordered by Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., the 20th Commandant of the Marine Corps.

Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to the Civil War as "the four-year War Between the States".[12] References to the "War Between the States" appear occasionally in federal and state court documents, including in Justice Harry Blackmun's landmark opinion in Roe v. Wade.[13] Their usage demonstrates the generality of the term's use. Roosevelt was born and raised in New York State, and Blackmun was born in southern Illinois but grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota.

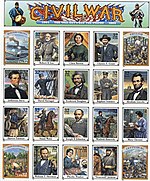

The names "Civil War" and "War Between the States" have been used jointly in some formal contexts. For example, to mark the war's centenary in the 1960s, the State of Georgia created the "Georgia Civil War Centennial Commission Commemorating the War Between the States". In 1994, the US Postal Service issued a series of commemorative stamps, "The Civil War: The War Between the States".

Historical terms in United States

[edit]War of the Rebellion/Slaveholders' Rebellion

[edit]

During and immediately after the war, US officials, Southern Unionists, and pro-Union writers often referred to Confederates as "Rebels". The earliest histories published in the northern states commonly refer to the war as "the Great Rebellion" or "the War of the Rebellion",[14] as do many war monuments, hence the nicknames Johnny Reb (and Billy Yank) for the participants.

Frederick Douglass delivered a speech entitled "The Slaveholders' Rebellion" on July 4, 1862, in Himrod, New York,[15] and John Harvey wrote The slaveholders' rebellion, and the downfall of slavery in America in 1865.[16]

The official US war records refer to the war as the "War of the Rebellion". The records were compiled by the US War Department in a 127-volume collection, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, which was published from 1881 to 1901. Historians commonly refer to the collection as the Official Records.[17][full citation needed]

War of Separation/Secession

[edit]"War of Separation" was occasionally used by people in the Confederacy during the war.[18] In most Romance languages, the words used to refer to the war translate literally to "War of Secession" (French: Guerre de Sécession, Italian: Guerra di secessione, Spanish: Guerra de Secesión, Portuguese: Guerra de Secessão, Romanian: Războiul de Secesiune), a name that is also used in Central and Eastern Europe: Sezessionskrieg is commonly used in German language, and Wojna secesyjna is used in Polish. (Walt Whitman calls it the "War of Secession" or the "Secession War" in his prose).

War for Southern Independence/The War of Northern Aggression

[edit]The names "War for Southern Independence" or "The War of Northern Aggression" and their variations are used by some Southerners to refer to the war.[19] That terminology aims to parallel usage of the American Revolutionary War. While popular on the Confederate side during the war (Stonewall Jackson regularly referred to the war as the "second war for independence"), the term lost popularity in the immediate aftermath of the Confederacy's defeat and its failure to gain independence. The term resurfaced slightly in the late 20th century.

A popular poem published in the early stages of hostilities was South Carolina. Its prologue referred to the war as the "Third War for Independence" since it named the War of 1812 as the second such war.[20] On November 8, 1860, the Charleston Mercury, a contemporary southern newspaper, stated, "The tea has been thrown overboard. The Revolution of 1860 has been initiated."[21]

In the 1920s, the historian Charles A. Beard used the term "Second American Revolution" to emphasize the changes brought on by the Union's victory. The term is still used by the Sons of Confederate Veterans organization but with the intent to represent the Confederacy's cause positively.[22][not specific enough to verify]

War for the Union

[edit]Some Southern Unionists and northerners used "The War for the Union", the title of a December 1861 lecture by the abolitionist leader Wendell Phillips.[citation needed]

Ordeal of the Union, a major eight-volume history published from 1947 to 1971 by the historian and journalist (Joseph) Allan Nevins, emphasizes the Union in the first volume's title, which also came to name the series. Because Nevins earned the Bancroft, Scribner, and National Book Award Prizes for books in his Ordeal of the Union series, his title may have been influential. However, the fourth volume is titled Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861, and the next four volumes use "War" in their titles. The sixth volume, War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863, picks up on that earlier thread in naming the conflict, but Nevins neither viewed Southern secession as revolutionary nor supported Southern apologist attempts to link the war with the American Revolution of 1775–1783.

War of Northern/Yankee Aggression

[edit]The name "War of Northern Aggression" has been used to indicate the Union as the belligerent party in the war.[23][24] The name arose during the Jim Crow era of the 1950s when it was coined by segregationists who tried to equate contemporary efforts to end segregation with 19th-century efforts to abolish slavery.[25][26][27][better source needed] The name has been criticized by historians such as James M. McPherson,[28] as the Confederacy "took the initiative by seceding in defiance of an election of a president by a constitutional majority"[28] and "started the war by firing on the American flag".[28]

Since the free states and most non-Yankee groups (Germans, Dutch-Americans, New York Irish and southern-leaning settlers in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois) showed opposition to waging the Civil War,[29] other Confederate sympathizers have used the name "War of Yankee Aggression"[30] to indicate the Civil War as a Yankee war, not a Northern war per se.[31]

Conversely, the "War of Southern Aggression" has been used by those who assert that the Confederacy was the belligerent party. They maintain that the Confederacy started the war by initiating combat at Fort Sumter.[28][32][33]

Miscellaneous

[edit]Other names for the conflict include "The Confederate War", "Buchanan's War", "Mr. Lincoln's War", and "Mr. Davis's War".[34][35][36] In 1892, a Washington, D.C. society of war-era nurses took on the name National Association of Army Nurses of the Late War,[37] with "late" meaning simply "recent". More euphemistic terms are "The Late Unpleasantness"[38] and "The Recent Unpleasantness".[39][40] Other postwar names in the South included "The War of the Sections" and "The Brothers' War", especially in the border states.[18]

Names of battles and armies

[edit]| Date | Southern name | Northern name |

|---|---|---|

| July 21, 1861 | First Manassas | First Bull Run |

| August 10, 1861 | Oak Hills | Wilson's Creek |

| October 21, 1861 | Leesburg | Ball's Bluff |

| January 19, 1862 | Mill Springs | Logan's Cross Roads |

| March 7–8, 1862 | Elkhorn Tavern | Pea Ridge |

| April 6–7, 1862 | Shiloh | Pittsburg Landing |

| May 31 – June 1, 1862 | Seven Pines | Fair Oaks |

| June 26, 1862 | Mechanicsville | Beaver Dam Creek |

| June 27, 1862 | Gaines's Mill | Chickahominy River |

| August 29–30, 1862 | Second Manassas | Second Bull Run |

| September 1, 1862 | Ox Hill | Chantilly |

| September 14, 1862 | Boonsboro | South Mountain |

| September 14, 1862 | Burkittsville | Crampton's Gap |

| September 17, 1862 | Sharpsburg | Antietam |

| October 8, 1862 | Perryville | Chaplin Hills |

| December 31, 1862 – January 2, 1863 |

Murfreesboro | Stones River |

| February 20, 1864 | Olustee | Ocean Pond |

| April 8, 1864 | Mansfield | Sabine Cross Roads |

| September 19, 1864 | Winchester | Opequon |

There is a disparity between the sides in naming some of the battles of the war. The Union forces frequently named battles for bodies of water or other natural features that were prominent on or near the battlefield, but Confederates most often used the name of the nearest town or artificial landmark. The novelist and historian Shelby Foote claimed that many Northerners were urban and regarded bodies of water as noteworthy, but many Southerners were rural and regarded towns as noteworthy.[42] That caused many battles to have two widely used names.

However, not all of the disparities are based on those naming conventions. Many modern accounts of Civil War battles use the names established by the North. However, for some battles, the Southern name has become the standard. The National Park Service occasionally uses the Southern names for its battlefield parks located in the South, such as Manassas and Shiloh. In general, naming conventions were determined by the victor of the battle.[43] Examples of battles with dual names are shown in the table.

Civil War armies were also named in a manner reminiscent of the battlefields since Northern armies were frequently named for major rivers (Army of the Potomac, Army of the Tennessee, Army of the Mississippi), and Southern armies for states or geographic regions (Army of Northern Virginia, Army of Tennessee, Army of Mississippi).

Units smaller than armies were named differently in many cases. Corps were usually written out (First Army Corps or simply First Corps), but a postwar convention developed to designate Union corps by using Roman numerals (XI Corps). Often, particularly with Southern armies, corps were more commonly known by the name of the leader (Hardee's Corps, Polk's Corps).

Union brigades were given numeric designations (1st, 2nd, etc.), but Confederate brigades were frequently named after their commanding general (Hood's Brigade, Gordon's Brigade). Confederate brigades so named retained the name of the original commander even when they were commanded temporarily by another man; for example, at the Battle of Gettysburg, Hoke's Brigade was commanded by Isaac Avery and Nicholl's Brigade by Jesse Williams. Nicknames were common in both armies, such as the Iron Brigade and the Stonewall Brigade.

Union artillery batteries were generally named numerically and Confederate batteries by the name of the town or county in which they were recruited (Fluvanna Artillery). Again, they were often simply referred to by their commander's name (Moody's Battery, Parker's Battery).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See titles listed in Oscar Handlin et al., Harvard Guide to American History (1954) pp 385–398.

- ^ "The Civil War". National Park Service.[dead link]

- ^ Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, Chapter IV

- ^ Proclamation, August 12, 1861.

- ^ Message to the Senate, May 26, 1862

- ^ F. Ballard, ed. (1984). "The Gettysburg address". America's Great Speeches. New York, NY: Random House. pp. 43–45.

- ^ Keegan, John, The American Civil War: A Military History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26343-8.

- ^ Wolseley, Garnet, Viscount Wolseley. The American Civil War: An English View. Reprint, Revised. Edited by James A. Rawley. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1964. ISBN 978-0-8117-0093-1.

- ^ Parish, Peter J. (April 1975). The American Civil War. New York: Holmes & Meier, U.S. ISBN 978-0-8419-0197-1.

- ^ "Civil War or War Between the States?". North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Warwick, et al., The Brig Amy, 67 U.S. 635, *636, 673 (1862)

- ^ Michael Waldman, My Fellow Americans, p. 111; also, Disc 1 Track 19

- ^ Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 139 (1973), see also Dairyland Greyhound Park, Inc. v. Doyle, 719 N.W.2d 408, 449 (Wis., 2006) ("Prior to the War Between the States all but three states had barred lotteries.")

- ^ Henry S. Foote, War of the Rebellion; Or, Scylla and Charybdis, New York: Harper & Bros., 1866; Horace Greeley, The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–64, 2 vols., Hartford, Conn.: O.D. Case & Co., 1864, 1866; Henry Wilson, The History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America, 3 vols, Boston: J. R. Osgood & Co., 1872–1877.

- ^ Noel, Tricia (June 20, 2021), "LOOKING BACK: The Slaveholders' rebellion: Frederick Douglass’ Fourth of July in Himrod", Finger Lakes Times, accessed 2021-12-14

- ^ Harvey, John (1865). The slaveholders' rebellion, and the downfall of slavery in America. Hawk-eye Steam Book and Job Printing Establishment.

- ^ [1][dead link] – Cornell University – Accessed 2010-11-28

- ^ a b Coulter, E. Merton (1950). The Confederate States of America, 1861–1865. ISBN 978-0-807-10007-3. pp. 60–61.

- ^ "Davis, Burke (1982), The Civil War: Strange and Fascinating Facts, New York: The Fairfax Press. ISBN 0-517-37151-0, pp. 79–80.

- ^ War Songs and Poems of the Southern Confederacy 1861–1865, H. M. Wharton, compiler and editor, Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books, 2000, ISBN 0-7858-1273-3, p. 69.

- ^ The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns. Dir. Ken Burns, Narr. David McCullough, Writ. and prod. Ken Burns. PBS DVD Gold edition, Warner Home Video, 2002, ISBN 0-7806-3887-5.

- ^ "Sons of Confederate Veterans". Sons of Confederate Veterans.

- ^ Benen, Steve (February 11, 2009). "War of Northern Aggression". The Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ Safire, William (2008). "euphemisms, political". Safire's Political Dictionary (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780195340617.

A fine euphemistic difference is still drawn about this war. Northerners say Civil War, but many Southerners say War Between the States or a tongue-in-cheek War of Northern Aggression.

- ^ ""The War of Northern Aggression" as Modern, Segregationist Revisionism". Dead Confederates, A Civil War Era Blog. 2011-06-21. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ Hall, Andy (June 21, 2011). "The War of Northern Aggression as Modern, Segregationist Revisionism". Dead Confederates: A Civil War Blog. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

[R]outinely employed by Southern segregationists to draw parallels between the civil rights struggles of the mid-20th century and the conflict of a hundred years before, to enlist the memory of Confederate ancestors in opposition to federal court-mandated processes like the desegregation of public schools and integration of public facilities.

- ^ Hall, Andy (June 27, 2011). ""War of Northern Aggression", Cont". Dead Confederates: A Civil War Blog. WordPress. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

[C]learly a modern term, one that first starts appearing in newspapers in the mid-1950s, often in conjunction with the Civil War Centennial or, more disturbingly, as part of the rhetoric wielded by segregationists against the federal courts.

- ^ a b c d McPherson, James M. (January 19, 1989). "The War of Southern Aggression". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

[T]he South took the initiative by seceding in defiance of an election of a president by a constitutional majority. Never mind that the Confederacy started the war by firing on the American flag.

- ^ Phillips, Kevin P.; The Emerging Republican Majority, pp. 28–29 ISBN 9780691163246

- ^ Murray, Williamson, and Wei-siang Hsieh, Wayne; A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War, pp. 10–11 ISBN 1400882907

- ^ Lipset, Seymour; Party Coalitions in the 1980s, p. 211 ISBN 1412830494

- ^ McPherson, James M. (April 18, 1996). Drawn with the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-511796-7.

- ^ McAfee, Ward M. (December 30, 2004). Citizen Lincoln. Nova Science. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-59454-112-4.

Lincoln knew that by simply remaining calm and steady in the face of Confederate demands, hotheaded Confederates themselves would fire the first shots, making the conflict that followed a war of southern aggression. ... As Fort Sumter was reduced to rubble, the closing words of Lincoln's inaugural were recalled: 'In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.'

- ^ Walter John Raymond. Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms, p. 14 (Brunswick, 1992)

- ^ "Civil War Women". CivilWarAcademy.com. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Birkner, Michael (September 20, 2005). "Buchanan's Civil War". Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ Scott, Kate M. (1910). In honor of the National Association of Civil War Army Nurses. the Citizens Executive Committee of Atlantic City, New Jersey.

- ^ Richard Hopwood Thornton, American Dialect Society. An American glossary: being an attempt to illustrate certain Americanisms upon historical principles, Volume 1, p. 527 (Lippincott, 1912)

- ^ Alex Leviton. Carolinas, Georgia and the South Trips, p. 117 (Lonely Planet 2009)

- ^ Elaine Marie Alphin An Unspeakable Crime: The Prosecution and Persecution of Leo Frank, p. 23 (Carolrhoda Books 2010)

- ^ Daniel Harvey Hill (1887–1888). "The Battle of South Mountain, or Boonsboro'. Fighting for Time at Turner's and Fox's Gaps". In Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel (ed.). Battles & Leaders of the Civil War. New York: The Century Co. p. 559.

- ^ The Civil War, Geoffrey Ward, with Ric Burns and Ken Burns, 1990, "Interview with Shelby Foote".

- ^ Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8117-2868-3. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Catton, Bruce, The Coming Fury: The Centennial History of the Civil War, Volume 1, Doubleday, 1961, ISBN 0-641-68525-4

- Coski, John M., "The War between the Names", North and South magazine, vol. 8, no. 7., January 2006.

- Musick, Michael P., "Civil War Records: A War by Any Other Name", Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives, Summer 1995, Vol. 27, No. 2.

- US War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, US Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Wittichen, Mrs. Murray Forbes, "Let's Say 'War Between the States'", Florida Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, 1954.