The Good Huswifes Jewell

Title page of 1596 edition | |

| Author | Thomas Dawson |

|---|---|

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Subject | Cookery |

| Publisher | Edward White |

Publication date | 1585 |

| Publication place | England |

| Pages | 53 double-page spreads |

The Good Huswifes Jewell is an English cookery book by the cookery and housekeeping writer Thomas Dawson, first published in 1585. It includes recipes for medicines as well as food. To the spices found in Medieval English cooking, the book adds herbs, especially parsley and thyme. Sugar is used in many of the dishes, along with ingredients that are uncommon in modern cooking like violets and rosewater.

The book includes recipes still current, such as pancakes, haggis, and salad of leaves and flowers with vinaigrette sauce, as well as some not often made, such as mortis, a sweet chicken pâté. Some dishes have familiar names, such as trifle, but different ingredients from those used today.

The Jewell is the first English cookery book to give a recipe for sweet potatoes.

Context

[edit]The Elizabethan age represented the period of transition from Medieval to modern. Cookery was changing as trade brought new ingredients, and fashion favoured new styles of cooking, with, for example, locally grown herbs as well as imported spices. Cooking came to be seen as a subject in its own right, rather than being part of medicine or books of "secrets".[1] Little is known of the book's author, Thomas Dawson, beyond the bare fact that he published several books on cooking including also his 1620 Booke of Cookerie.[1] Such books were becoming available to a wider audience than the aristocratic households of the Middle Ages, hence the "huswife" of Dawson's title.[2]

Book

[edit]Overview

[edit]The Good Huswifes Jewell gives recipes for making fruit tarts using fruits as varied as apple, peach, cherry, damson, pear, and mulberry. For stuffing for meat and poultry, or as Dawson says "to farse all things", he recommends using the herbs thyme, hyssop, and parsley, mixed with egg yolk, white bread, raisins or barberries, and spices including cloves, mace, cinnamon and ginger, all in the same dish.[3] A sauce for pork was made with white wine, broth, nutmeg, and the herbs rosemary, bay, thyme, and marjoram.[4]

Familiar recipes include pancakes, which were made with cream, egg yolks, flour, and a little ale; the cook was directed "let the fire be verie soft, and when the one side is baked, then turn the other, and bake them as dry as ye can without burning."[5] Blancmange appears as "Blewmanger", made of cream, eggs, sugar and rosewater.[6]

Approach

[edit]The recipes are written as goals, like "To make a Tarte of Spinadge", with instructions to achieve the goal. Quantities are given, if at all, only in passing, either with vague phrases like "a good handful of persely and a few sweet hearbs", or as "the yolks of 4 hard egges".[7] Cooking times are given only occasionally, as "let them seeth a quantitye of an houre".[8] Directions as to the fire are given where necessary, as "boyle it in a chafing dish of coales" or "with a fyre of Wood beate it the space of two houres".[9]

The recipe for a salad with a vinaigrette dressing runs as follows (from the 1596 edition):[10]

To Make a Sallet of All Kinde of Hearbes

Take your hearbes and picke them very fine into faire water, and picke your flowers by themselues, and washe them al cleane, and swing them in a strainer, and when you put them into a dish, mingle them with Cowcumbers or Lemmons payred and sliced, and scrape Suger, and put in vineger and Oyle, and throwe the flowers on the toppe of the sallet, and of every sorte of the aforesaide things and garnish the dish about with the foresaide things, and harde Egges boyled and laide about the dish and upon the sallet.

This recipe is taken up by the National Trust, which calls it "Stourhead herb and flower salad."[11]

Contents

[edit]The 1596 edition is structured as follows:[12]

- Order of meat how they must be served at the Table, with their sauces for flesh daies at dinner.

- A Booke of Cookerie (39 double pages)

- Approued pointes of Cookerie / Approued pointes of Husbandrie / Approued Medicines for sundry diseases

- The table of the book following gathered according to euery folio throughout the whole Booke [index]

- Part II (1597)

The 1597 edition of Part II is structured as follows:[12]

- A Booke of Cookerie (72 single pages)

- The Booke of Caruing and Sewing (38 single pages, not numbered)

- Tearmes of a Caruer

- (The book of Caruing)

- How to make Marchpaine and Ipocras

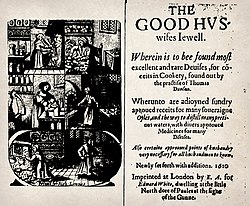

Illustrations

[edit]

The book is illustrated only with a frontispiece. In the 1610 edition this has six kitchen scenes, including a three-legged pot over an open fire, cordials being distilled, a bread oven, and pots and roasts on a spit over a fire.[a]

Medicines

[edit]Dawson's recipes included medicines, some of which involved sympathetic magic. The Good Huswife's Jewell described "a tart to provoke courage in either man or woman", calling for the brains of male sparrows.[13] Torn sinews are healed by taking "worms while they be nice", crushing them and laying them on to the sore "and it will knit the sinew that be broken in two".[14]

Editions

[edit]- First edition, Edward White, 1585

- Second edition, Edward White, 1596

- ---reprinted 1996, Southover Press, with introduction by Maggie Black

- Third edition, Edward White, 1610

A book called The Second Part of the good Hus-wiues Jewell was published by Edward White in 1597.

Reception

[edit]The celebrity chef Clarissa Dickson Wright comments on Dawson's trifle that it differs from the modern recipe, as it consists only of "a pinte of thicke Creame", seasoned with sugar, ginger and rosewater, and warmed gently for serving.[15] She notes, also from the Good Huswife's Jewell, that the Elizabethans had a strong liking for sweet things, "richly demonstrated" in Dawson's "names of all things necessary for a banquet":[16]

Sugar, cinnamon, liquorice, pepper, nutmegs, all kinds of saffron, sanders, comfits, aniseeds, coriander, oranges, pomegranate seeds, Damask water, turnsole, lemons, prunes, rose water, dates, currants, raisins, cherries conserved, barberries conserved, rye flower, ginger, sweet oranges, pepper white and brown, mace, wafers.[16]

The culinary historian Alison Sim notes that "the closest the Tudors came to sponge were sponge-like biscuits", which could be raised with eggs or with yeast; the "cracknels" in the Jewell were boiled before baking, being put into boiling water where they would sink and then rise to the top. Sim notes that Dawson's "fine bisket bread" had to be beaten for two hours.[17]

The culinary historian Ken Albala describes the Jewell as an "important cookbook", and observes that it is the first English cookery book to give a recipe for sweet potatoes (which had arrived in Europe after Columbus's voyages), while also listing "old medieval standbys". He comments that there are several pudding recipes, both savoury and sweet, including haggis. He notes, too, that it gives instructions for the marzipan figures "so beloved on the Elizabethan banquetting table."[18]

The culinary historian Stephen Mennell calls the Jewell "more distinctively English" than the Boke of Kervynge and the Boke of Cokery from earlier in the century. It, like Gervase Markham's The English Huswife of 1615, was aimed at a more general audience, not only aristocrats but "housewives", which Mennell glosses as "gentlewomen concerned with the practical tasks of running households". Hence the book could treat not only food but medicines, dairy-work, brewing, and preserving.[2]

The historian Joanna Opaskar notes that the Elizabethans used what "may seem odd ingredients today", such as rosewater and violets, and that Dawson provides a recipe for salmon with violets, the recipe calling for slices of onion with violets, oil, and vinegar. She also notes that sugar was included "in almost every kind of dish", as well as spices that we would use in "sweet rather than savory dishes."[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The frontispiece however states its publisher is Rich[ard] Lowndes rather than Edward White, and appears to be borrowed from the 1670 The Queen-like Closet of Hannah Woolley, which was published by Lowndes.

References

[edit]Page references to Dawson are from the 1596 edition; each folio or double-page spread has a single number, so there are twice as many actual sides as numbers.

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, Joan (2013). Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories. Ashgate Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4094-7578-1.

- ^ a b Mennell, Stephen (1996). All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. University of Illinois Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-252-06490-6.

- ^ Forgeng, Jeffrey L. (19 November 2009). Daily Life in Elizabethan England. ABC-CLIO. pp. 176–179. ISBN 978-0-313-36561-4.

- ^ Dawson, pages 14–15

- ^ "The Good Huswifes Jewell - pancakes and puddings". The British Library. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Dawson, page 28

- ^ Dawson, page 1

- ^ Dawson, page 2

- ^ Dawson, page 13

- ^ Willan, Anne; Cherniavsky, Mark (3 March 2012). The Cookbook Library: Four Centuries of the Cooks, Writers, and Recipes That Made the Modern Cookbook. University of California Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-0-520-24400-9.

- ^ "Stourhead herb and flower salad". The National Trust. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b Dawson, 1596–97

- ^ Ashley, Leonard R. N. (1988). Elizabethan Popular Culture. Popular Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-87972-427-6.

- ^ "Review of 'The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England By Ian Mortimer'". We Love This Book. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011) A History of English Food. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-905-21185-2. Page 123

- ^ a b Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011) A History of English Food. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-905-21185-2. Page 147

- ^ Sim, Alison (2012). Food & Feast in Tudor England. History Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7524-9542-2.

- ^ Albala, Ken (2003). Food in Early Modern Europe. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-313-31962-4.

- ^ Opaskar, Joanna (2008). Food in Shakespeare's Plays Life "consists of Eating and Drinking". University of Houston Clear Lake (PhD Thesis). p. 11. ISBN 978-0-549-60612-3.

External links

[edit]- Gode Cookery PDFs including The Good Huswifes Jewell 1596 and The Second part of the good Hus-wiues Jewell 1597

- Good Huswifes Jewell 1596 (.txt)