The Accomplisht Cook

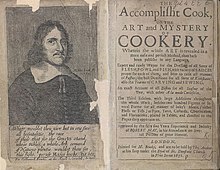

Frontispiece of 1671 edition | |

| Author | Robert May |

|---|---|

| Subject | Cookery |

| Publisher | Nathaniel Brooke |

Publication date | 1660 |

| Publication place | England |

The Accomplisht Cook is an English cookery book published by the professional cook Robert May in 1660, and the first to group recipes logically into 24 sections. It was much the largest cookery book in England up to that time, providing numerous recipes for boiling, roasting, and frying meat, and others for salads, puddings, sauces, and baking. Eight of the sections are devoted to fish, with separate sections for carp, pike, salmon, sturgeon, and shellfish. Another section covers only eggs; and the next only artichokes.

The book was one of the few cookery books published during the Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell, and free of the plagiarism common at its time. It made early use of two ingredients brought to Europe from the Americas, the potato and the turkey.

Context

[edit]Robert May was from the age of ten a cook, working for aristocratic Roman Catholic and royalist employers beginning with Lady Dormer. She sent him to study cooking for five years in France, after which he served a seven-year apprenticeship in London.[1] He became known for his book The Accomplisht Cook, which dwarfed earlier cookery texts by its size and scope. Despite the Catholic context, the book does not place special emphasis on Catholic fast and feast days; nor, despite May's training, is it heavy with French influence, though Alan Davidson notes that he borrowed 35 recipes for eggs from François Pierre La Varenne's Le Cuisinier françois.[2] May's text became widely available with the 1994 reprint in facsimile of the 1685 edition, and its historical introduction by Marcus Bell.[2]

Book

[edit]Approach

[edit]May's recipes included customs from the Middle Ages, alongside European dishes such as French bisque and Italian brodo (broth),[3] with about 20 percent of the book devoted to soups.[3] May provides a large number of recipes for venison, as for sturgeon, but balances his more elaborate and costly recipes with some for simple dishes.[4] The book contains no fewer than sixteen recipes for eel.[5]

The recipes are presented entirely as instructions, without lists of ingredients, and not necessarily in order; he can write "Then have a rost Capon minced", requiring the cook to have already taken, prepared and roasted the capon, a process that takes some hours, in the middle of a recipe (for Olio Podrida). Quantities, if given, are mentioned in passing. Thus he may mention "put them a boiling in a Pipkin of a Gallon", or "the juyce of two or three Oranges", or he may write "and put into beaten Butter", leaving the cook to judge the quantity required.[4]

Contents

[edit]The book is organised into 24 broad sections,[6] but within these, there is sometimes little sign of structure. Thus in Section I, after the elaborate Spanish Olio Podrida, he provides four recipes for (bone-)marrow pies to accompany the Olio; then three ways to make a "bisk"; seven ways to boil a chine of veal or mutton; three ways to make barley broth, again involving meat for its "gravy", and so on. The same section contains "To make several sorts of Puddings", ranging from blood pudding and haggis to sweet rice pudding flavoured with nutmeg, cloves, mace, currants, and dates.[6]

The early sections on meat are not restricted to beef, lamb, and pork, though there is a whole section (II) on beef. The book includes many recipes for venison, meaning red deer and fallow deer. Hunting was important to May's aristocratic readers and to ordinary farmers; deer were killed both for their meat and to protect crops. May presents recipes for other wild species, including birds not now considered game, such as bitterns, gulls, and herons.[4]

Sections XIII to XX are devoted to the preparation of fish and associated dishes;[6] these include 38 recipes for sturgeon, now a rare fish in British waters, but evidently in May's time not unusual.[4] Salmon receives less attention; it was a common fish and not highly-prized, but there is a recipe for salmon with oranges.[4] The sections are listed below:

- I: Boiling

- II: Beef

- III: Heads

- IV: Roasting

- V: Sallets

- VI: Frying

- VII: Puddings

- VIII: Souces and Jellies

- IX: Baking

- X: Fruit

- XI: Made Dishes

- XII: Creams

- XIII: Carps

- XIV: Pikes

- XV: Salmon, Bace, or Mullet

- XVI: Turbut, Plaice, Flounders, and Lampry

- XVII: Eels, Conger, Lump, and Soals

- XVIII: Sturgeon

- XIX: Shell-Fish

- XX: Pottages for Fish-Days

- XXI: Eggs

- XXII: Artichocks

- XXIII: Diet for the Sick

- XXIV: Feeding of Poultrey

The book also contains a memoir of the author.[6]

Illustrations

[edit]

The first edition contained a Frontispiece of the author, while the fifth edition of 1685 had in addition "two hundred Figures of several Forms for all manner of bak’d Meats, (either Flesh, or Fish) as, Pyes Tarts, Custards; Cheesecakes, and Florentines, placed in Tables, and directed to the Pages they appertain to."[7]

Recipes

[edit]Among May's many recipes for fish is "To make minced Pies of Ling, Stock-fish, Harberdine, &c.":[8]

Being boiled, take it [the fish] from its skin and bones, and mince it with some pippins [apples], season it with nutmeg, cinnamon, ginger, pepper, caraway-seed, currans, minced raisons, rose-water, minced lemon peel, sugar, slic't [sliced] dates, white wine, verjuice [sour fruit juice, in this case probably from apples], and butter, fill your pyes, bake them, and ice them.

His recipes for puddings include "To make a Hasty-Pudding in a Bag":[9]

Boil a pint of thick cream with a spoonful of flour, season it with nutmeg, sugar, and salt, wet the cloth and flour it, then pour in the cream being hot into the cloth, and when it is boil'd butter it as a hasty pudding. If it be well made, it will be as good as a Custard.

Reception

[edit]The celebrity cook and author Clarissa Dickson Wright covers The Accomplisht Cook in detail. She notes that few other cookery books were published during the Commonwealth of England, and that the book is free of the plagiarism usual at the time. She therefore considers the book to have a "freshness" and to be revealing of well-to-do life in 17th century England, with its many recipes for venison and for fish such as sturgeon and salmon. She is struck that the recipes for birds such as heron include instructions for fattening them after capture, while godwits, knots, grey plovers and curlews were "force-fed in the way that the French force-feed geese today for pâté de foie gras". She notes that May offers "sophisticated and ambitious" recipes alongside simple dishes like porridge and sausages, while the presence of haggis reveals a definite Scottish influence. She notes, too, his openness to foreign recipes, with an "incredibly complicated stew" from Spain, an Olio Podrida containing a rack of mutton, a knuckle of veal, a capon (minced), 12 young pigeons, 8 young chickens, ten sweetbreads, ten palates, and lemons, pomegranates, grapes, saffron and almonds which "presumably .. give the dish its Spanish aspect".[4]

The historian of food Polly Russell, writing in the Financial Times, is struck by the quantity of food May recommends for Christmas, including 20 first courses and 19 second courses. Even the "Grand Sallet" (salad) contained a whole capon and a breast of lamb or veal. Russell sees the lavishness of the book as a reaction to the former dominance of the Puritans over English life.[10]

The journalist Vera Rule, writing in The Guardian, argues that May's writing resembled that of his contemporary, the physician William Harvey, communicating exciting facts "through urgent active verbs and imperative terms - leach that brawn, allay that pheasant, unbrace that mallard".[11] She notes that both menus and customs were in transition (from Mediaeval to Early Modern): novelties included tricks like wrapping puddings in a cloth before boiling, whereas May tells readers to place a ring of bits of toast around a stew, so that diners could eat by dipping, rather than make use of new-fangled forks. She comments that his cooking was far from new, though he takes for granted two recent arrivals from the Americas, the potato and the turkey. On the other hand, Rule observes that May was still completely Mediaeval in his taste; for example, he liked to see live birds bursting from a fake "pye", complete with a mock battle on the table. Old Byzantine or Middle Eastern cuisine, brought to Europe by Islamic conquerors, similarly features with "saffron, almonds, East Indies spices".[11] She concludes that "His ubiquitous luxury garnish was molten butter frothed with sharp orange juice".[11]

The historian of food Kate Colquhoun notes that the book was the first to group recipes logically into sections, and that May was the first cook in Britain to illustrate his book with "woodcuts of spectacular pastry work that would set the standard for the next hundred years". Calling The Accomplisht Cook "one of the most clearly written collections of the century", she points out that a tenth of the book was about bisks, broths with a little meat or fish. She describes the book as "in some ways an old-fashioned collection with savoury dishes laden with sugar and dried fruits", yet embracing the "new French style" with plenty of butter, recipes that called for snails, and sauces that contained cream.[12]

Editions

[edit]The following editions appeared in the 17th century:[6][13]

- May, Robert (1660). The Accomplisht Cook (1st ed.). Printed by R.W. for Nath. Brooke at the sign of the Angel in Cornhill.

- ——— (1665). The Accomplisht Cook (2nd ed.). Printed by R.W. for Nath. Brooke at the sign of the Angel in Cornhill.

- ——— (1671). The Accomplisht Cook (3rd ed.). Printed by J. Winter for Nath. Brooke at the Angel in Cornhill near the Royal Exchange.

- ——— (1678). The Accomplisht Cook (4th ed.). Printed for Obadiah Blagrave at the Bear in St. Pauls Church-Yard, near the little north-door.

- ——— (1685). The Accomplisht Cook (5th ed.). Printed for Obadiah Blagrave at the Bear and Star in St. Pauls Church-Yard.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Accomplisht Cook". British Library. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b Davidson, Alan (2014). Tom Jaine (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^ a b ChefTalk.com. "History Of Soup". Articles. cheftalk.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Dickson Wright, Clarissa (2011). A History of English Food. Random House. pp. 188–199.

- ^ Schweid, Richard (2002). "Consider the Eel". Gastronomica. 2 (2): 14–19. doi:10.1525/gfc.2002.2.2.14. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2002.2.2.14.

- ^ a b c d e May, Robert (1685) [1665]. "The Project Gutenberg EBook of The accomplisht cook, by Robert May". eBook #22790 (main). gutenberg.org. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ May, Robert (1685). The Accomplisht Cook, Or The Art & Mystery Of Cookery. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ May, Robert (1685). "Section XVIII. Or, The Sixth Section of Fish.". The Accomplisht Cook. Gutenberg. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ May, Robert (1685). "Section VII. The most Excellent Ways of making All sorts of Puddings.". The Accomplisht Cook. Gutenberg. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Russell, Polly (30 November 2012). "The history cook: The Accomplisht Cook". The Financial Times. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Rule, Vera (1 April 2000). "First leach your brawn". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Colquhoun, Kate (2008) [2007]. Taste: The Story of Britain through its Cooking. Bloomsbury. pp. 160, 166. ISBN 978-0-747-59306-5.

- ^ May, Robert. "The Accomplisht Cook". Worldcat. Retrieved 31 January 2016.