Illmatic

| Illmatic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 19, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | 1992–1993[1] | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:48 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Nas chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Illmatic | ||||

| ||||

Illmatic is the debut studio album by the American rapper Nas. It was released on April 19, 1994, by Columbia Records. After signing with the label with the help of MC Serch, Nas recorded the album in 1992 and 1993 at Chung King Studios, D&D Recording, Battery Studios, and Unique Recording Studios in New York City. The album's production was handled by DJ Premier, Large Professor, Pete Rock, Q-Tip, L.E.S., and Nas himself. Styled as a hardcore hip hop album, Illmatic features multi-syllabic internal rhymes and inner-city narratives based on Nas' experiences growing up in the Queensbridge Houses in Queens, New York.

The album debuted at number 12 on the US Billboard 200 chart, selling 59,000 copies in its first week. Initial sales fell below expectations and its five singles failed to achieve significant chart success. Despite the album's low initial sales, Illmatic received rave reviews from most music critics, who praised its production and Nas' lyricism. On January 17, 1996, the album was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America, and on December 11, 2001, it earned a platinum certification after shipping 1,000,000 copies in the United States. As of February 6, 2019, the album had sold 2 million copies in the United States.

Since its initial reception, Illmatic has been recognized by writers and music critics as a landmark album in East Coast hip hop. Its influence on subsequent hip hop artists has been attributed to the album's production and Nas' lyricism, and contributed to the revival of the New York City rap scene, introducing a number of stylistic trends to the region. The album is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential hip hop albums of all time, appearing on numerous best album lists by critics and publications.[3] Billboard wrote in 2015 that "Illmatic is widely seen as the best hip-hop album ever".[4] In 2020, the album was ranked by Rolling Stone at number 44 on its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and in the following year,[5] it was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Background

[edit]As a teenager, Nas wanted to pursue a career as a rapper and enlisted his best friend and neighbor, Willy "Ill Will" Graham, as his DJ.[6] Nas initially went by the nickname "Kid Wave" before adopting the alias "Nasty Nas".[6] At the age of fifteen, he met producer Large Professor from Flushing, Queens, who introduced him to his group Main Source. Nas made his recorded debut with them on the opening verse on "Live at the Barbeque" from their 1991 album Breaking Atoms.[7] Nas made his solo debut on his 1992 single "Halftime" for the soundtrack to the film Zebrahead. The single added to the buzz surrounding Nas, earning him comparisons to the highly influential golden age rapper Rakim.[8] Despite his buzz in the underground scene, Nas did not receive an offer for a recording contract and was rejected by major rap labels such as Cold Chillin' and Def Jam Recordings. Nas and Ill Will continued to work together, but their partnership was cut short when Graham was murdered by a gunman in Queensbridge on May 23, 1992;[9] Nas' brother was also shot that night, but survived.[10] Nas has cited that moment as a "wake-up call" for him.[10]

In mid-1992, MC Serch, whose group 3rd Bass had dissolved, began working on a solo project and approached Nas.[11] At the suggestion of producer T-Ray, Serch collaborated with Nas for "Back to the Grill", the lead single for Serch's 1992 solo debut album Return of the Product.[12] At the recording session for the song, Serch discovered that Nas did not have a recording contract and subsequently contacted Faith Newman, an A&R executive at Sony Music Entertainment.[13] As Serch recounted, "Nas was in a position where his demo had been sittin' around, 'Live at the Barbeque' was already a classic, and he was just tryin' to find a decent deal .... So when he gave me his demo, I shopped it around. I took it to Russell first, Russell said it sounded like G Rap, he wasn't wit' it. So I took it to Faith. Faith loved it, she said she'd been looking for Nas for a year and a half. They wouldn't let me leave the office without a deal on the table."[14]

Once MC Serch assumed the role of executive producer for Nas' debut project, he attempted to connect Nas with various producers. Numerous New York-based producers were eager to work with the up-and-coming rapper and went to Power House Studios with Nas. Among those producers was DJ Premier,[14] recognized at the time for his raw and aggressive jazz sample-based production and heavy scratching, and for his work with rapper Guru as a part of hip hop duo Gang Starr.[15] After his production on Lord Finesse & DJ Mike Smooth's Funky Technician (1990) and Jeru the Damaja's The Sun Rises in the East (1994), Premier began recording exclusively at D&D Studios in New York City, before working with Nas on Illmatic.[15][16]

Recording

[edit][Nas] didn't know how he was gonna come in, but he just started going because we were recording. I'm actually yelling, "We're recording!" and banging on the [vocal booth] window. "Come on, get ready!" You hear him start the shit: Rappers .... And then everyone in the studio was like, "Oh, my God", 'cause it was so unexpected. He was not ready. So we used that first verse. And that was when he was up and coming, his first album. So we was like, "Yo, this guy is gonna be big."

—DJ Premier on the recording of the song "N.Y. State of Mind"[17]

Prior to recording, DJ Premier listened to Nas' debut single, and later stated "When I heard 'Halftime', that was some next shit to me. That's just as classic to me as 'Eric B For President' and 'The Bridge'. It just had that type of effect. As simple as it is, all of the elements are there. So from that point, after Serch approached me about doing some cuts, it was automatic. You'd be stupid to pass that up even if it wasn't payin' no money."[14] Serch later noted the chemistry between Nas and DJ Premier, recounting that "Primo and Nas, they could have been separated at birth. It wasn't a situation where his beats fit their rhymes, they fit each other."[14] While Serch reached out to DJ Premier, Large Professor contacted Pete Rock to collaborate with Nas on what became "The World Is Yours".[18] Shortly afterwards, L.E.S. (a DJ in Nas's Queensbridge neighborhood) and A Tribe Called Quest's Q-Tip chose to work on the album.[14] "Life's a Bitch" contains a cornet solo performed by Nas' father, Olu Dara, with features by Brooklyn-based rapper AZ.[14]

In an early promotional interview, Nas claimed that the name "Illmatic" (meaning "beyond ill" or "the ultimate") was a reference to his incarcerated friend, Illmatic Ice.[19] Nas later described the title name as "supreme ill. It's as ill as ill gets. That shit is a science of everything ill."[20] At the time of its recording, expectations in the hip hop scene were high for Illmatic.[14] In a 1994 interview for The Source, which dubbed him "the second coming" (referring to Rakim), Nas spoke highly of the album, saying that "this feels like a big project that's gonna affect the world [...] We in here on the down low [...] doing something for the world. That's how it feels, that's what it is. For all the ones that think it's all about some ruff shit, talkin' about guns all the time, but no science behind it, we gonna bring it to them like this."[14] AZ recounted recording on the album, "I got on Nas' album and did the 'Life's a Bitch' song, but even then I thought I was terrible on it, to be honest. But once people started hearing that and liking it, that's what built my confidence. I thought, 'OK, I can probably do this.' That record was everything. To be the only person featured on Illmatic when Nas is considered one of the top men in New York at that time, one of the freshest new artists, that was big."[14] During the sessions, Nas composed the song "Nas Is Like", which he later recorded as a single for his 1999 album I Am....[21]

Regarding the album's opening song "N.Y. State of Mind", producer DJ Premier later said, "When we did 'N.Y. State of Mind,' at the beginning when he says, 'Straight out the dungeons of rap / Where fake niggas don't make it back,' then you hear him say, 'I don't know how to start this shit,' 'cause he had just written it. He's got the beat running in the studio, but he doesn't know how he's going to format how he's going to convey it. So he's going, 'I don't know how to start this shit,' and I'm counting him in [to begin his verse]. One, two, three. And then you can hear him go, 'Yo,' and then he goes right into it."[17]

Themes

[edit]

Illmatic contains highly discerning treatment of its subject matter: gang rivalries, desolation, and the ravages of urban poverty.[22][23] Nas, who was twenty years old when the album was released, focuses on depicting his own experiences, creating highly detailed first-person narratives that deconstruct the troubled life of an inner city teenager. Jeff Weiss of Pitchfork describes the theme of the album as a "[S]tory of a gifted writer born into squalor, trying to claw his way out of the trap. It's somewhere between The Basketball Diaries and Native Son ..."[24] The narratives featured in Illmatic originate from Nas' own experiences as an adolescent growing up in the Queensbridge housing projects located in the Long Island City-section of Queens.[25] Nas said in an interview in 2001: "When I made Illmatic I was a little kid in Queensbridge trapped in the ghetto. My soul was trapped in Queensbridge projects."[26] In a 2012 interview, he explained his inspiration for exploring this subject matter:

[W]hen my rap generation started, it was about bringing you inside my apartment. It wasn't about being a rap star; it was about anything other than. I want you to know who I am: what the streets taste like, feel like, smell like. What the cops talk like, walk like, think like. What crackheads do — I wanted you to smell it, feel it. It was important to me that I told the story that way because I thought that it wouldn't be told if I didn't tell it. I thought this was a great point in time in the 1990s in [New York City] that needed to be documented and my life needed to be told.[27]

Nas's depictions of project life alternate from moments of pain and pleasure to frustration and braggadocio.[28] The columnist for OhWord.com wrote: "[His] narrative voice swerves between personas that are cynical and optimistic, naïve and world-weary, enraged and serene, globally conscious and provincial".[25] Jeff Weiss describes the "enduring image" often associated with Nas' narrated stream of consciousness: "[A] baby-faced Buddha monk in public housing, scribbling lotto dreams and grim reaper nightmares in dollar notebooks, words enjambed in the margins. The only light is the orange glow of a blunt, bodega liquor, and the adolescent rush of first creation. Sometimes his pen taps the paper and his brain blanks. In the next sentence, he remembers dark streets and the noose."[24] Critic and blogger Kenny Waste comments on the significance of Queensbridge as a setting in Illmatic, writing, "The songs are made up largely of recollections or Nas describing his emotions, which range from feeling trapped to overt optimism about his abilities to escape the 'hands of doom'. But they always remain within the walls of his Queensbridge home."[29]

Along with its narratives, Illmatic is distinct for its many portrayals and descriptions of places, people, and interactions.[30] In his songs, Nas often depicts the corners and boulevards of Queensbridge, while mentioning the names of streets, friends, local crews and drug dealers, and utilizing vernacular slang indigenous to his hometown.[30] Poet and author Kevin Coval describes this approach to songwriting as that of a "hip-hop poet-reporter...rooted in the intimate specificity of locale."[30] Commenting on Nas' use of narrative, Sohail Daulatzai, Professor of Film and Media Studies at University of Southern California, compares the album to cinema, citing its "detailed descriptions, dense reportage, and visually stunning rhymes..." In Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic, he writes: "Like the 1965 landmark masterpiece film The Battle of Algiers, which captured the Algerian resistance against French colonialism, Illmatic brilliantly blurred the lines between fiction and documentary, creating a heightened sense of realism and visceral eloquence for Nas' renegade first-person narratives and character-driven odes."[31]

Drug violence

[edit]Many of the themes found in Illmatic revolve around Nas' experience living in an environment where poverty, violence, and drug use abound. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, residents of Queensbridge experienced intense violence, as the housing development was overrun by the crack epidemic. Illmatic contains imagery inspired by the prevalence of street crime. In "N.Y. State of Mind", Nas details the trap doors, rooftop snipers, street corner lookouts, and drug dealers that pervade his urban dreamscape.[32] Sohail Daulatzai describes this language as "chilling" and suggests that it "harrowingly describes and imagines with such surreal imagery, with so much noir discontent and even more fuck-you ambition, the fragile and tenuous lives of ghetto dwellers..."[32] Author Adam Mansbach interprets Nas' violent aesthetics as a metaphoric device meant to authenticate the rough edges of his persona: "Nas's world and worldview are criminal and criminalized. Hence, he uses metaphoric violence as a central trope of his poetic."[33] Writer and musician Gregory Tate regards this violent imagery as part of a trend towards dark subject matter that came to prevail among East Coast rappers in the hardcore hip hop scene. He writes, "[S]ome of the most memorably dark, depressive but flowing lyrics in hip hop history were written by Nas, Biggie, and members of the Wu-Tang Clan on the death knell of the crack trade."[34]

Other writers, such as Mark Anthony Neal, have described these lyrical themes as a form of "brooding introspection", disclosing the tortured dimensions of drug crime and its impressions on an adolescent Nas.[35] Sam Chennault wrote, "Nas captures post-crack N.Y.C. in all its ruinous glory ... [r]ealizing that drugs were both empowering and destructive, his lyrics alternately embrace and reject the idea of ghetto glamour".[23] According to Steve Juon of RapReviews.com, Nas "illustrates the Queensbridge trife life of his existence, while at the same time providing hope that there is something greater than money, guns and drugs."[36] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post described Nas' coming-of-age experience as "balancing limitations and possibilities, distinguishing hurdles and springboards, and acknowledging his own growth from roughneck adolescent to a maturing adult who can respect and criticize the culture of violence that surrounds him.[37]

Artistic credibility

[edit]The content of Illmatic informed notions of artistic authenticity.[38] The promotional press sheet that accompanied the album's release implied Nas' refusal to conform to commercial trends, stating: "While it's sad that there's so much frontin' in the rap world today, this should only make us sit up and pay attention when a rapper comes along who's not about milking the latest trend and running off with the loot."[24] At the time of the album's release, the hip hop community was embroiled in a debate about artistic authenticity and commercialism in popular music.[38] Chicago rapper Common describes in the preface to Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic the concerns that were felt by him and his contemporaries: "It was that serious for so many of us. We didn't just grow up with hip hop; we grew up with hip hop as hip hop was also growing, and so that made for a very close and intimate relationship that was becoming more and more urgent – and we felt it. Our art was being challenged in many ways as the moneymen began to sink their teeth into us."[39]

In the context of this debate, music writers have interpreted Illmatic as an admonishment for hip hop purists and practitioners.[40][29] In the opening track, "The Genesis", Nas bemoans the lack of legitimacy among other MCs in the projects, insisting that he has "Been doin' this shit since back then."[29] Citing songs such as "Life's a Bitch", Guthrie Ramsay Jr. argues that Nas "set a benchmark for rappers in an artistic field consumed by constantly shifting notions of 'realness', authenticity, and artistic credibility."[41] Sohail Daulatzai writes: "Though Illmatic was highly anticipated release, far from under the radar, Nas's taking it back to 'the dungeons of rap' was...a kind of exorcism or purging ('where fake niggas don't make it back') that was at the very least trying to claim a different aesthetic of resistance and rebellion that was all too aware of hip-hop's newfound mainstream potential."[38]

Musical endowment

[edit]In addition to its lyrical content, many writers have commented on the thematic significance of Illmatic's musical endowments. "Drawing on everything from old school hip hop, to blues, to fairly avant-garde jazz compositions," writes music blogger Kenny Waste, "the sampling choices within Illmatic reflect an individual with not only a deep appreciation for but also a deep knowledge of music."[29] Musicologist and pianist Guthrie Ramsay Jr. describes Illmatic as "an artistic emblem" that "anchors itself in the moment while reminding us that powerful musical statements often select past material and knowledge for use in the present and hope for the future."[38] Kevin Coval considers the sampling of artists Craig G and Biz Markie in 'Memory Lane' as an attempt to build upon the hip hop tradition of Queens, most notably the Juice Crew All Stars.[30] These samples are intended to serve as tributes to "Nas' lyrical forebearers [sic] and around-the-way influences. He is repping his borough's hip hop canon."[30] The involvement of older artists, including Nas' father, has also been cited as a formative influence in the making of Illmatic. Author Adam Mansbach argues, "It's the presence of all these benevolent elders –his father and the cadre of big brother producers steering the album – that empowers Nas to rest comfortably in his identity as an artist and an inheritor of tradition, and thus find the space to innovate."[38]

Music writers have characterized the album's contents as a commentary on hip hop's evolution. As Princeton University professor Imani Perry writes, Illmatic "embodies the entire story of hip-hop, bearing all of its features and gifts. Nas has the raw lyrics of old schoolers, the expert deejaying and artful lyricism of the 1980s, the slice of hood life, and the mythic ... The history of hip-hop up to 1994 is embodied in Illmatic."[42] In the song, "Represent", Nas alludes to the Juice Crew's conflict with Boogie Down Productions, which arose as a dispute over the purported origins of hip hop. Princeton University professor Eddie S. Glaude Jr. claims that this "situates Queensbridge and himself within the formative history of hip-hop culture."[43] The opening skit, 'The Genesis,' contains an audio sample of the 1983 film, Wild Style, which showcased the work of early hip hop pioneers such as Grandmaster Flash, Fab Five Freddy, and the Rock Steady Crew. After the music of Wild Style is unwittingly rejected by one of his peers, Nas admonishes his friend about the importance of their musical roots. Kenny Waste suggests that embedded deep within this track "is a complex and subtle exposition on the themes of Illmatic."[29] Similarly, Professor Adilifu Nama of California State University Northridge writes, "'[T]he use of Wild Style ... goes beyond a simple tactic to imbue Illmatic with an aura of old-school authenticity. The sonic vignette comments on the collective memory of the hip hop community and its real, remembered, and even imagined beginning, as well as the pitfalls of assimilation, the importance of history, and the passing of hip-hop's 'age of innocence'."[44]

Lyricism

[edit]Illmatic has been noted by music writers for Nas' unique style of delivery and poetic substance.[28] His lyrics contain layered rhythms, multisyllabic rhymes, internal half rhymes, assonance, and enjambment.[30] Music critic Marc Lamont Hill of PopMatters elaborates on Nas' lyricism and delivery throughout the album, stating "Nas' complex rhyme patterns, clever wordplay, and impressive vocab took the art [of rapping] to previously unprecedented heights. Building on the pioneering work of Kool G Rap, Big Daddy Kane, and Rakim, tracks like 'Halftime' and the laid back 'One Time 4 Your Mind' demonstrated a [high] level of technical precision and rhetorical dexterity."[45] Hill cites "Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)" as "an exemplar of flawless lyricism",[45] while critic Steve Juon wrote that the lyrics of the album's last song, "It Ain't Hard to Tell", are "just as quotable if not more-so than anything else on the LP – what album could end on a higher note than this?":[36]

|

|

|

Focusing on poetic forms found in his lyrics, Princeton University professor Imani Perry describes Nas' performance as that of a "poet-musician" indebted to the conventions of jazz poetry. She suggests that Nas' lyricism might have been shaped by the "black art poetry album genre," pioneered by Gil Scott-Heron, The Last Poets, and Nikki Giovanni.[40] Chicago-based poet and music critic Kevin Coval attributes Nas' lyricism to his unique approach to rapping, which he describes as a "fresh-out-the-rhyme-book presentation": "It's as if Nas, the poet, reporter, brings his notebook into the studio, hears the beat, and weaves his portraits on top with ill precision, and comments on the rapper's vignettes of inner-city life, which are depicted using elaborate rhyme structures: "All the words, faces and bodies of an abandoned post-industrial, urban dystopia are framed in Nas's tightly packed stanzas. These portraits of his brain and community in handcuffs are beautiful, brutal and extremely complex, and they lend themselves to the complex and brilliantly compounded rhyme schemes he employs."[30]

Production

[edit]Illmatic garnered praise for its production. According to critics, the album's five major producers (Large Professor, DJ Premier, Pete Rock, Q-Tip and L.E.S.) extensively contributed to the cohesive atmospheric aesthetic that permeated the album, while still retaining each producers individual, trademark sound.[46][47] For instance, DJ Premier's production on the album is noted by critics for his minimalist style, which featured simple loops over heavy beats.[48] Charles Aaron of Spin wrote of the producers' contributions, "nudging him toward Rakim-like-rumination, they offer subdued, slightly downcast beats, which in hip hop today means jazz, primarily of the '70s keyboard-vibe variety".[49] Q magazine noted that "the musical backdrops are razor sharp; hard beats but with melodic hooks and loops, atmospheric background piano, strings or muted trumpet, and samples ... A potent treat."[47] One music critic wrote that "Illmatic is laced with some of the finest beats this side of In Control Volume 1".[48]

The majority of the album consists of vintage funk, soul, and jazz samples.[50] Commenting on the album and its use of samples, Pitchfork's Jeff Weiss claims that both Nas and his producers found inspiration for the album's production through the music of their childhood: "The loops rummage through their parent's collection: Donald Byrd, Joe Chambers, Ahmad Jamal, Parliament, Michael Jackson. Nas invites his father, Olu Dara to blow the trumpet coda on "Life's a Bitch". Jazz rap fusion had been done well prior, but rarely with such subtlety. Nas didn't need to make the connection explicit—he allowed you to understand what jazz was like the first time your parents and grandparents heard it."[24] Similarly, journalist Ben Yew comments on the album's nostalgic sounds, "The production, accentuated by infectious organ loop[s], vocal sample[s], and synthesizer-like pads in the background, places your mind in a cheerful, reminiscent, mood."[51]

Songs

[edit]The intro, "The Genesis", is composed as an aural montage that begins with the sound of an elevated train and an almost-inaudible voice rhyming beneath it. Over these sounds are two men arguing.[28] It samples Grand Wizard Theodore's "Subway Theme" from the 1983 film Wild Style, the first major hip hop motion picture.[50] Nas made another ode to Wild Style, while shooting the music video for his single, "It Ain't Hard to Tell", on the same stage as the final scene for the film.[52] His verse on "Live at the Barbeque" is played in the background of "The Genesis".[36] According to music writer Mickey Hess, in the intro, "Nas tells us everything he wants us to know about him. The train is shorthand for New York; the barely discernible rap is, in fact, his "Live at the Barbeque" verse; and the dialogue comes from Wild Style, one of the earliest movies to focus on hip hop culture. Each of these is a point of genesis. New York for Nas as a person, 'Live at the Barbeque' for Nas the rapper, and Wild Style, symbolically at least, for hip hop itself. These are my roots, Nas was saying, and he proceeded to demonstrate exactly what those roots had yielded."[28]

Setting the general grimy, yet melodic, tone of the album,[50] "N.Y. State of Mind" features a dark, jazzy piano sample courtesy of DJ Premier.[53] It opens with high-pitched guitar notes looped from jazz and funk musician Donald Byrd's "Flight Time" (1972), while the prominent groove of piano notes was sampled from the Joe Chambers composition "Mind Rain" (1978).[50] The lyrics of "N.Y. State of Mind" have Nas recounting his participation in gang violence and philosophizing that "Life is parallel to Hell, but I must maintain", while his rapping spans over forty bars.[54] "N.Y. State of Mind" focuses on a mindstate that a person obtains from living in Nas' impoverished environment.[36] Critic Marc Hill of PopMatters wrote that the song "provides as clear a depiction of ghetto life as a Gordon Parks photograph or a Langston Hughes poem."[45]

In other songs on Illmatic, Nas celebrates life's pleasures and achievements, acknowledging violence as a feature of his socio-economic conditions rather than the focus of his life.[28] "Life's a Bitch" contains a sample of The Gap Band's hit "Yearning for Your Love" (1980),[50] and has guest vocals from East New York-based rapper AZ.[53] It features Nas's father, Olu Dara, playing a trumpet solo as the music fades out.[53] A columnist for OhWord.com wrote that Dara's contribution to the song provides a "beautifully wistful end to a track that feels drenched in the dying rays of a crimson sunset over the city."[50] "The World Is Yours" provides a more optimistic narrative from Nas' viewpoint,[53] as he cites political and spiritual leader Gandhi as an influence in its verse, in contrast to the previous Scarface references of "N.Y. State of Mind".[55] While citing "Life's a Bitch" as "possibly the saddest hip-hop song ever recorded", Rhapsody's Sam Chennault wrote that "The World Is Yours" "finds optimism in the darkest urban crevices".[23] "The World Is Yours" was named the seventh greatest rap song by About.com.[56]

The nostalgic "Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)" contains a Reuben Wilson sample, which comprises the sound of a Hammond organ, guitar, vocals and percussion,[50] and adds to the track's ghostly harmonies.[57] Spence D. of IGN wrote that the lyrics evoke "the crossroads of old school hip hop and new school."[55] "One Love" is composed of a series of letters to incarcerated friends,[58] recounting mutual acquaintances and events that have occurred since the receiver's imprisonment,[45] and address unfaithful girlfriends, emotionally tortured mothers, and underdog loyalty.[59] The phrase "one love" signifies street loyalty in the song.[55] After delivering "shout-outs to locked down comrades", Nas chastises a youth who seems destined for prison in the final verse.[36] Produced by Q-Tip, "One Love" samples the double bass and piano from the Heath Brothers' "Smilin' Billy Suite Part II" (1975) and the drum break from Parliament's "Come In Out the Rain" (1970), complementing the track's mystical and hypnotic soundscape.[50]

"One Time 4 Your Mind" features battle rap braggadocio by Nas.[55] With a similar vibe as "N.Y. State of Mind", the rhythmic "Represent" has a serious tone, exemplified by Nas' opening lines, "Straight up shit is real and any day could be your last in the jungle/get murdered on the humble, guns will blast and niggas tumble".[53] While the majority of the album consists of funk, soul and jazz samples, "Represent" contains a sample of "Thief of Bagdad" by organist Lee Erwin from the 1924 film of the same name.[50] Nas discusses his lifestyle in an environment where he "loves committin' sins" and "life ain't shit but stress",[21] while describing himself as "The brutalizer, crew de-sizer, accelerator/The type of nigga who be pissin' in your elevator".[45] "It Ain't Hard to Tell" is a braggadocious rap.[28][60] It opens with guitars and synths of Michael Jackson's "Human Nature" (1983); the song's vocals are sampled for the intro and chorus sections, creating a swirling mix of horns and tweaked-out voices.[55] Large Professor looped in drum samples from Stanley Clarke's "Slow Dance" (1978) and saxophone from Kool & the Gang's "N.T." (1971).[50]

Artwork

[edit]On the vinyl and cassette pressings of Illmatic, the traditional side A and side B division are replaced with "40th Side North" and "41st Side South," respectively – the main streets that form the geographic boundaries that divide the Queensbridge housing projects. Professor Sohail Daulatzai views this labeling as significant, since it transforms Illmatic into "a sonic map." The album serves as the legend for Nas's ghetto cartography, as he narrates his experiences and those who live in the Queensbridge."[40] In a 2009 interview with XXL magazine, Nas discussed the purpose behind the album artwork among other promotional efforts, stating "Really the record had to represent everything Nasir Jones is about from beginning to end, from my album cover to my videos. My record company had to beg me to stop filmin' music videos in the projects. No matter what the song was about I had 'em out there. That's what it was all about for me, being that kid from the projects, being a poster child for that, that didn't exist back then."[20]

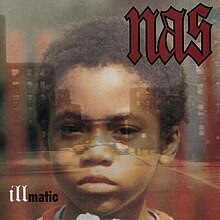

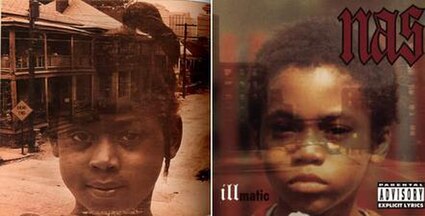

Album cover

[edit]The album cover of Illmatic features a picture of Nas as a child, which was taken after his father, Olu Dara, returned home from an overseas tour.[8] The original cover was intended to have a picture of Nas holding Jesus Christ in a headlock,[8] reflecting the religious imagery of Nas' rap on "Live at the Barbeque"; "When I was 12, I went to hell for snuffing Jesus".[14]

The accepted cover, designed by Aimee Macauley, features a photo of Nas as a child superimposed over a backdrop of a city block,[36] taken by Danny Clinch.[61] In a 1994 interview, Nas discussed the concept behind the photo of him at age 7, stating "That was the year I started to acknowledge everything [around me]. That's the year everything set off. That's the year I started seeing the future for myself and doing what was right. The ghetto makes you think. The world is ours. I used to think I couldn't leave my projects. I used to think if I left, if anything happened to me, I thought it would be no justice or I would be just a dead slave or something. The projects used to be my world until I educated myself to see there's more out there."[19] According to Ego Trip, the cover of Illmatic is "reputedly" believed to have been inspired by a jazz album, Howard Hanger Trio's A Child Is Born (1974) — whose cover also features a photograph of a child, superimposed on an urban landscape.[62] Nas has revealed that the inspiration for the album cover was derived from Michael Jackson. "I'm a big Michael Jackson fan," Nas has stated. "I'll tell you something I never said. On my album cover, you see me with the afro, that was kind of inspired by Michael Jackson – the little kid picture."[63]

Since its release, the cover art of Illmatic has gained an iconic reputation — having been subject to numerous parodies and tributes.[62] Music columnist Byron Crawford later called the cover for Illmatic "one of the dopest album covers ever in hip-hop."[64] Commenting on the cover's artistic value, Rob Marriott of Complex writes, "Illmatic's poignant cover matched the mood, tone, and qualities of this introspective album to such a high degree that it became an instant classic, hailed as a visual full of meaning and nuance."[65] XXL called the album cover a "high art photo concept for a rap album" and described the artwork as a "noisy, confusing streetscape looking through the housing projects and a young boy superimposed in the center of it all."[66] The XXL columnist compared the cover to that of rapper Lil Wayne's sixth studio album Tha Carter III (2008), stating that it "reflects the reality of disenfranchised youth today."[66]

On the song "Shark Niggas (Biters)" from his debut album Only Built 4 Cuban Linx... (1995), rapper Raekwon with Ghostface Killah criticized the cover of The Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die (1994), which was released a few months after Illmatic, for featuring a picture of a baby with an afro, implying that his cover had copied the idea from Nas.[67] This generated long-standing controversy between the rappers, resulting in an unpublicized feud which Nas later referenced in the song "Last Real Nigga Alive" from his sixth studio album God's Son (2002).[citation needed]

Commercial performance

[edit]Illmatic was released on April 19, 1994, through Columbia Records in the United States.[61] The album later received international distribution that same year in countries including France, the Netherlands, Canada and the United Kingdom.[68][69][70][71] In its first week of release, Illmatic made its debut on the Billboard 200 at number 12, selling 59,000 copies.[72] In spite of this, initial record sales fell below expectations.[8] The album's five radio singles failed to obtain considerable chart success. The lead single, "Halftime", only charted on the Hot Rap Singles chart at number 8, while "Life's a Bitch" did not chart at all.[73] The album suffered from extensive bootlegging prior to its release. "Regional demand was so high," writes music critic Jeff Weiss, "that Serch claimed he discovered a garage with 60,000 bootlegged copies."[24] While initial sales were low, the album was eventually certified Gold in sales by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) on January 17, 1996, after shipping 500,000 copies; the RIAA later certified Illmatic Platinum on December 11, 2001, following shipments in excess of a million copies.[72] Charting together with the original Illmatic (according to the rules by Billboard), the twentieth anniversary release, Illmatic XX, sold 15,000 copies in its first week returning to Billboard 200 at number 18, with an 844% sales gain.[74] As of April 20, 2014[update], the album sold 1,686,000 copies in the US.[74] and was certified gold by the Canadian Recording Industry Association in April 2022, for shipments in excess of 50,000 copies in Canada.[75] The album has sold 2 million copies in the United States as of February 6, 2019.

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[76] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 9/10[78] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Source | |

| Spin | 3/3[49] |

| USA Today | |

Illmatic was met with widespread acclaim from critics,[82] many of whom hailed it as a masterpiece.[83] NME called its music "rhythmic perfection",[78] and Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune cited it as the best hardcore hip hop album "out of the East Coast in years".[46] Dimitri Ehrlich of Entertainment Weekly credited Nas for giving his neighborhood "proper respect" while establishing himself, and said that the clever lyrics and harsh beats "draw listeners into the borough's lifestyle with poetic efficiency."[76] Touré, writing for Rolling Stone, hailed Nas as an elite rapper because of his articulation, detailed lyrics, and Rakim-like tone, all of which he said "pair [Illmatic's] every beautiful moment with its harsh antithesis."[79] Christopher John Farley of Time praised the album as a "wake-up call to [Nas'] listeners" and commended him for rendering rather than glorifying "the rough world he comes from".[10] USA Today's James T. Jones IV cited his lyrics as "the most urgent poetry since Public Enemy" and commended Nas for honestly depicting dismal ghetto life without resorting to the sensationalism and misogyny of contemporary gangsta rappers.[81] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post praised Nas for "balancing limitations and possibilities, distinguishing hurdles and springboards, and acknowledging his own growth from roughneck adolescent to a maturing adult who can respect and criticize the culture of violence that surrounds him".[37]

Some reviewers were less impressed. Heidi Siegmund of the Los Angeles Times found most of Illmatic hampered by "tired attitudes and posturing", and interpreted its acclaim from East Coast critics as "an obvious attempt to wrestle hip-hop away from the West".[77] Charles Aaron of Spin felt that the comparisons to Rakim "will be more deserved" if Nas can expand on his ruminative lyrics with "something more personally revealing".[49] In his initial review for Playboy, Robert Christgau called it "New York's typically spare and loquacious entry in the post-gangsta sweepstakes" and recommended it to listeners who "crave full-bore authenticity without brutal posturing".[84]

The Source

[edit]Upon its release, The Source gave Illmatic a five mic rating,[80] their highest rating and a prestigious achievement at the time,[85] given the magazine's influence in the hip hop community.[8] Jon Shecter, co-founder of The Source, had received a copy of the album eight months before its scheduled release, and soon lobbied for it to receive a five mic rating.[86] At the time, it was unheard of for a debuting artist to receive the coveted rating.[86] The rating did not come without its share of controversy.[87] Only two years prior, Dr. Dre's groundbreaking The Chronic failed to earn the coveted rating, despite redefining the musical landscape of hip hop. It was later revealed that while everybody at the magazine knew it was worthy of a five mic rating, they decided to comply with the strict policy of staying away from a perfect score.[88][65][87] Despite receiving criticism over his staff's earlier review of The Chronic, Reginald Dennis continues to defend the decision to award Illmatic with the magazine's highest rating.[86]

Retrospect

[edit]| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 89/100[89] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| And It Don't Stop | A[90] |

| The Austin Chronicle | |

| Consequence of Sound | A[92] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Mojo | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[95] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| XXL | 5/5[98] |

Since its initial reception, Illmatic has been viewed by music writers as one of the quintessential hip hop recordings of the 1990s, while its rankings near the top of many publications' "best album" lists in disparate genres have given it a reputation as one of the greatest hip hop albums of all time.[99][100] Jon Pareles of The New York Times cited Illmatic as a "milestone in trying to capture the 'street ghetto essence'".[101] The album has been described by a number of writers and critics as "classic".[2][102][103][104] Chris Ryan, writing in The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), called Illmatic "a portrait of an artist as a hood, loner, tortured soul, juvenile delinquent, and fledgling social critic," and wrote that it "still stands as one of rap's crowning achievements".[97] In a retrospective review for MSN Music, Christgau said the record was "better than I thought at the time for sure—as happens with aesthetes sometimes, the purists heard subtleties principled vulgarians like me were disinclined to enjoy", although he still found it inferior to The Notorious B.I.G.'s debut album Ready to Die (1994).[105] In 2002, Prefix Mag's Matthew Gasteier re-examined Illmatic and its musical significance, stating:

Illmatic is the best hip-hop record ever made. Not because it has ten great tracks with perfect beats and flawless rhymes, but because it encompasses everything great about hip-hop that makes the genre worthy of its place in music history. Stylistically, if every other hip-hop record were destroyed, the entire genre could be reconstructed from this one album. But in spirit, Illmatic can just as easily be compared to Ready to Die, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, and Enter the Wu-Tang as it can to Rites of Spring, A Hard Day's Night, Innervisions, and Never Mind the Bollocks. In Illmatic, you find the meaning not just of hip-hop, but of music itself: the struggle of youth to retain its freedom, which is ultimately the struggle of man to retain his own essence.[54]

Illmatic has been included in "best album" lists in disparate genres. Pitchfork listed the album at number 33 on its list of the Top 100 Albums of the 1990s, and the publication's columnist Hartley Goldstein called the album "the meticulously crafted essence of everything that makes hip-hop music great; it's practically a sonic strand of the genre's DNA."[106] It was listed as one of 33 hip hop/R&B albums in Rolling Stone's "Essential Recordings of the 90s".[107] It was ranked number five in "The Critics Top 100 Black Music Albums of All Time" and number three in Hip Hop Connection's "Top 100 Readers Poll".[108][109] The album was ranked number four in Vibe's list of the Top 10 Rap Albums and number two on MTV's list of The Greatest Hip Hop Albums of All Time.[110] In 1998, it was selected as one of The Source's 100 Best Rap Albums.[111] In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked the album number 44 on its list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[112] On March 30, 2004, Illmatic was remastered and re-released with a bonus disc of remixes and new material produced by Marley Marl and Large Professor, in commemoration of its tenth anniversary.[113] Upon its 2004 re-release, Marc Hill of PopMatters dubbed it "the greatest album of all time" and stated, "Ten years after its release, Illmatic stands not only as the best hip-hop album ever made, but also one of the greatest artistic productions of the twentieth century."[45] The album was included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[114] A February 19, 2014 Village Voice cover story ranked Illmatic as the Most New York City album ever.[115] In 2021, the album was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[116]

Impact and legacy

[edit]

Illmatic has been noted as one of the most influential hip hop albums of all time, with pundits describing it as an archetypal East Coast hip hop album.[6][98] Jeff Weiss of Pitchfork writes: "No album better reflected the sound and style of New York, 94",[24] and John Bush of AllMusic has characterized it as "one of the quintessential East Coast records".[16] Along with the critical acclaim of the Wu-Tang Clan's debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (1993) and the success of The Notorious B.I.G.'s debut Ready to Die (1994), Illmatic was instrumental in restoring interest in the East Coast hip hop scene. "Rarely has the birthplace of hip-hop," wrote Rob Marriott of Complex, "been so unanimous in praise of a rap record and the MC who made it."[65] In addition to bringing attention to East Coast hip hop more broadly, Illmatic is also credited with returning Queensbridge's local hip hop scene to prominence after years of obscurity.[8][117]

Illmatic featured production from a broad stable of producers, including Large Professor, Pete Rock, and DJ Premier.[118] These producers' contributions to Illmatic became influential in shaping the soundscape of New York's regional scene,[65] and popularized the previously uncommon practice of assembling many big-name producers on a single hip hop album.[8][119][120]

Illmatic has been regarded as a landmark recording in the development of hardcore hip hop. Professor Sohail Dalautzai of the University of Southern California characterizes the album as having "unified the disparate threads of urban rebellion" in hip hop,[120] and Duke University's Mark Anthony Neal situates Nas "at the forefront of a renaissance of East Coast hip hop" in which "a distinct East Coast style of so-called gangsta rap appeared".[40] The album has been described as an iconic release in the boom bap subgenre.[121][122] Illmatic's significant success has been viewed as shifting attention away from other styles of hip hop, including West Coast G-funk[123] and "Native Tongues-inspired alternative rap".[2] Despite its divergences from the prevailing styles of West Coast hip hop, Illmatic has still been identified as influential on some West Coast artists such as Tupac Shakur.[124]

Upon its release, Illmatic brought a renewed focus on lyricism to hip hop. Nas' content, verbal pace, and intricate internal rhyme patterns inspired several rappers to modify their lyrical abilities.[8][19] Rappers who have been identified as influenced by Nas' lyrical style include Jay-Z,[65] Ghostface Killah,[125] and Detroit rapper Elzhi.[126] Author and poet Kevin Coval describes the lyricism on Illmatic as a shift "from punch lines and hot lines to whole thought pictures manifest in rhyme form."[30] Just as hip-hop poetics were being written and published for the first time on paper, Nas provided a sonic production that definitively captured "the poetic response" to hip hop music.[30]

Musicians who have acknowledged Illmatic's influence upon them include conscious rappers Talib Kweli[127] and Lupe Fiasco,[128] the producers Just Blaze[129] and 9th Wonder,[130] and platinum-selling artists Wiz Khalifa,[131] Alicia Keys[132] and The Game.[133] Common's album Be is said to have been modeled on Illmatic;[134][135][136] Kendrick Lamar's album Good Kid, M.A.A.D City has been compared to Nas' album as well.[137][138] Illmatic has also received attention from scholars: one prominent example is the 2009 book Born to Use Mics, edited by Michael Eric Dyson and Sohail Daulatzai, a compilation of reflections on the album by various academic and artistic professionals.[139]

Because Illmatic received such immense critical acclaim, Nas' subsequent studio albums were frequently compared to it, and were often regarded as failing to live up to Illmatic's standard.[28][45] Nas' albums from the later 1990s, including It Was Written, I Am..., and Nastradamus, were criticized for their incorporation of crossover sensibilities and radio-friendly hits.[8][140] Nas was viewed as having made a comeback in the twenty-first century, beginning with 2001's Stillmatic and the 2002 projects God's Son and The Lost Tapes,[8] but fans continue to elevate Illmatic as his definitive work.[45] In 2014, Nas announced Illmatic XX, the 20th Anniversary Edition of the original album Illmatic, released April 15, 4 days prior to the 20th Anniversary of the original's release date (April 19). Illmatic XX includes a remastered version of Illmatic, an extra disc of demos, remixes, and unreleased records from that era of Nas' career. He announced his plans for a tour where he will perform the whole album front to back on each stop.[141][142]

Track listing

[edit]| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Genesis" |

| 1:45 | |

| 2. | "N.Y. State of Mind" |

| DJ Premier | 4:53 |

| 3. | "Life's a Bitch" (featuring AZ) |

| 3:30 | |

| 4. | "The World Is Yours" |

| Pete Rock | 4:50 |

| 5. | "Halftime" | Large Professor | 4:20 | |

| 6. | "Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)" |

| DJ Premier | 4:08 |

| 7. | "One Love" | Q-Tip | 5:25 | |

| 8. | "One Time 4 Your Mind" |

| Large Professor | 3:18 |

| 9. | "Represent" |

| DJ Premier | 4:12 |

| 10. | "It Ain't Hard to Tell" |

| Large Professor | 3:22 |

| Total length: | 39:48 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Life's a Bitch" (Remix; featuring AZ) |

| Rockwilder | 3:00 |

| 2. | "The World Is Yours" (Remix) |

| Vibesmen | 3:56 |

| 3. | "One Love" (Remix) | Nick Fury | 5:09 | |

| 4. | "It Ain't Hard to Tell" (Remix) |

| Nick Fury | 3:26 |

| 5. | "On the Real" | Marley Marl | 3:26 | |

| 6. | "Star Wars" |

| Large Professor | 4:08 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I'm a Villain" |

| Jae Supreme | 4:30 |

| 2. | "The Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Show on WKCR October 28, 1993" (featuring 6'9", Jungle and Grand Wizard) | Stretch Armstrong | 7:46 | |

| 3. | "Halftime" (Butcher Remix) | Joe "The Butcher" Nicolo | 4:36 | |

| 4. | "It Ain't Hard to Tell" (Remix) | Large Professor | 2:49 | |

| 5. | "One Love" (LG Main Mix) | The LG Experience | 5:32 | |

| 6. | "Life's a Bitch" (Arsenal Mix; featuring AZ) | Def Jef & Meech Wells | 3:30 | |

| 7. | "One Love" (One L Main Mix; featuring Sadat X) | Godfather Don, The Groove Merchantz & Victor Padilla | 5:43 | |

| 8. | "The World Is Yours" (Tip Mix) | Q-Tip | 4:28 | |

| 9. | "It Ain't Hard to Tell" (The Stink Mix) | Dave Scratch | 3:20 | |

| 10. | "It Ain't Hard to Tell" (The Laidback Remix) | The Creators | 3:36 |

Sample credits

[edit]|

The Genesis

N.Y. State of Mind

Life's a Bitch The World Is Yours

Halftime

|

Memory Lane (Sittin' in da Park)

One Love

One Time 4 Your Mind

Represent

It Ain't Hard to Tell

|

Personnel

[edit]

|

|

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[155] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[156] | Platinum | 300,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[157] | 2× Platinum | 2,000,000‡ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Accolades

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Citations are needed for each of these accolades. (February 2024) |

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| About.com | United States | 100 Greatest Hip-Hop Albums[99] | 2008 | 1 | ||

| Best Rap Albums of 1994[158] | 2008 | 1 | ||||

| 10 Essential Hip-Hop Albums[159] | 2008 | 1 | ||||

| Blender | 500 CDs You Must Own Before You Die[160] | 2003 | * | |||

| Ink Blot | Albums of the 90s | 2002 | 11 | |||

| MTV | The Greatest Hip Hop Albums of All Time[161] | 2005 | 2 | |||

| Music Underwater | Top 100 Albums 1990–2003 | 2004 | 45 | |||

| Robert Dimery | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die | 2006 | * | |||

| Rolling Stone | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time | 2020 | 44 | |||

| The Essential Recordings of the 90s | 1999 | * | ||||

| Apple Music | 100 Best Albums[162] | 2024 | 39 | |||

| The Source | 100 Best Rap Albums[111] | 1998 | * | |||

| The Critics Top 100 Black Music Albums of All Time[108] | 2006 | 5 | ||||

| Spin | Top 100 Albums of the Last 20 Years | 2005 | 17 | |||

| Stylus | Top 101–200 Albums of All time | 2004 | 143 | |||

| Tom Moon | 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die[163] | 2008 | * | |||

| Vibe | 51 Albums representing a Generation, a Sound and a Movement | 2004 | * | |||

| Top 10 Rap Albums[47] | 2002 | 4 | ||||

| Village Voice | Albums of the Year | 2000 | 33 | |||

| Hip Hop Connection | United Kingdom | Top 100 Readers Poll[109] | 2003 | 3 | ||

| Mojo | Mojo 1000, the Ultimate CD Buyers Guide | 2001 | * | |||

| NME | The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time[164] | 2013 | 27 | |||

| Albums of the Year | 1994 | 33 | ||||

| The New Nation | Top 100 Albums by Black Artists | 2004 | 5 | |||

| Select | Albums of the Year | 1994 | 18 | |||

| The 100 Best Albums of the 90s | 1996 | 99 | ||||

| Juice | Australia | The 100 (+34) Greatest Albums of the 90s | 1999 | 101 | ||

| Exclaim! | Canada | 100 Records That Rocked 100 Issues | 2000 | * | ||

| Les Inrockuptibles | France | 50 Years of Rock'n'Roll | 2004 | * | ||

| Spex | Germany | Albums of the Year | 1994 | 9 | ||

| Juice | The Hundred Most Influential Rap Albums Ever | 2002 | 4 | |||

| OOR | Netherlands | Albums of the Year | 1994 | 42 | ||

| VPRO | 299 Nominations of the Best Album of All Time | 2006 | * | |||

| The Movement | New Zealand | The 101 Best Albums of the 90s | 2004 | 51 | ||

| Dance de Lux | Spain | The 25 Best Hip-Hop Records | 2001 | 25 | ||

| Rock de Lux | The 150 Best Albums from the 90s | 2000 | 134 | |||

| Pop | Sweden | Albums of the Year | 1994 | 9 | ||

| (*) designates lists that are unordered. | ||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Legacy Recordings Celebrates 25th Anniversary of Nas 'It Was Written' with Newly Expanded Digital Edition". Legacy Recordings. June 24, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Huey, Steve. "Illmatic – Nas". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ^ Petrusich, Amanda. Pop and Rock Listings: Nas Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved on March 20, 2009.

- ^ "The 10 Best Rappers of All Time". Billboard. November 12, 2015. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

20 years later, Illmatic is widely seen as the best hip-hop album ever, a flawless blend of vivid street poetry and dream-team producers ....

- ^ "Janet Jackson and Kermit the Frog Added to National Recording Registry". The New York Times. March 24, 2021. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Foster, S. (2004). "Bridging the Gap (Part 2)". Ave Magazine, pp. 48–54.

- ^ Huey, Steve. Review: Breaking Atoms. Allmusic. Retrieved on January 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cowie, Del. Nas: Battle Ready Archived June 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Exclaim!. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ Nasty Nas | Nas Fanpage – Untitled in stores NOW!! – Ill Will Records[permanent dead link]. Nasty-Nas.de.tl. Retrieved on November 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c Farley, Christopher John (June 20, 1994). "Music: Street Stories". Time. New York. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Huey, Steve. 3rd Bass: Biography. Allmusic. Retrieved on February 22, 2009.

- ^ Wheeler, Austin. "T-Ray Interview Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Elemental: 63. 2004.

- ^ Wheeler, Austin. "T-Ray Interview Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Elemental: 64. 2004. Archived from the original Archived September 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine on August 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Shecter, Jon."The Second Coming". Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link). The Source: 45–46, 84. April 1994. - ^ a b Bush, John. DJ Premier: Biography. Allmusic. Retrieved on February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Bush, John. The Sun Rises in the East: Overview. Allmusic. Retrieved on February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b NY State of mind-fiilistely ja samalla pettymys-olo topic[permanent dead link]. Basso Media. Retrieved on January 19, 2009.

- ^ "Talib Kweli & Pete Rock Talk C.L. Smooth & More". UPROXX. June 7, 2021. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Nas: The Genesis Archived January 15, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. Retrieved on May 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Markman, Rob. The Genesis Archived March 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. XXL. Retrieved on March 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Wang (2003), p. 120.

- ^ Boyd (2004), p. 91.

- ^ a b c Chennault, Sam. Reviews: Illmatic Archived March 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Rhapsody. Retrieved on March 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Illmatic Reissue Review Archived March 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on March 8, 2013

- ^ a b R.H.S. A Queens Lineage: Mobb Deep – The Infamous Archived July 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Oh Word. Retrieved on February 9, 2006.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Rebel In America" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic. pp. 33–60

- ^ NPR Nas On Marvin Gaye's Marriage, Parenting And Rap Genius Archived September 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed on July 31, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g ego trip. Hess (2007), pp. 345–346.

- ^ a b c d e Waste, Kenny "Niggaz Don't Listen": Communication in Nas's "The Genesis" Archived November 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed on April 12, 2013

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "All The Words Past The Margins". Adam Mansbach. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic. pp. 2–3

- ^ a b Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Rebel to America:'N.Y. State of Mind' After the Towers Fells" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 117–28.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "All The Words Past The Margins: Adam Mansbach and Kevin Coval talk understandable smooth shit" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 245–54.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Elegy for Illmatic." Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 237–40.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Memory Lane: On Jazz, Hip Hop, and Fathers." Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 117–28.

- ^ a b c d e f RapReviews: Illmatic Archived May 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. RapReviews. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Harrington, Richard (May 4, 1994). "Recordings". The Washington Post. Style section, p. c.07. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "This is Illmatic: A Song for My Father, A Letter to My Son" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 61–74.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Preface" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic. pp. ix – xi

- ^ a b c d Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "It Was Signified: 'The Genesis'" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic. pp. 13–32

- ^ "2005 Pop Conference Bios/Abstracts". Archived from the original on December 27, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link). emplive.org. Retrieved on January 20, 2007. - ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "It Ain't Hard to Tell': A Story of Lyrical Transcendence." Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 195–212.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Represent: Queensbridge and the Art of Living" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 179–194.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "It Was Signified: 'The Genesis'" Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 13–32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hill, Marc Lamont (May 24, 2004). "Nas: Illmatic [Anniversary Edition]". PopMatters. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c Kot, Greg (May 5, 1994). "Nas Has It". Chicago Tribune. Tempo section, p.7. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c Columnist. "Review: Illmatic". Q: 142. March 1997.

- ^ a b iTunes Store: DJ Premier Productions Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Apple Inc. Retrieved on February 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c Aaron, Charles (August 1994). "Nas: Illmatic". Spin. Vol. 10, no. 5. New York. p. 84. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Love, Dan. Deconstructing Illmatic Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Oh Word. Retrieved on February 15, 2008.

- ^ Yew, Ben."Retrospect for Hip-Hop: A Golden Age on Record?". Archived from the original on March 15, 2007. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link). Proudflesh: A New Afrikan Journal of Culture, Politics & Consciousness. Retrieved on October 20, 2006. - ^ Nas Video Retrospective: 'It Ain't Hard to Tell' Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Boombox. Retrieved on February 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e MVRemix: Illmatic Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. MVRemix Media. Retrieved on February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Nas: A look at a hip-hop masterpiece, ten years removed Archived November 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. PrefixMag. Retrieved on February 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e D. Spence. Review: Illmatic (Anniversary Reissue) Archived January 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. IGN. Retrieved on February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Top 100 Rap Songs – These are the Top 100 Rap Songs that helped shaped Hip-Hop – Top 100 Rap Songs". Rap.about.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Ling, Tony. Treble: Illmatic Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Treble Media. Retrieved on February 22, 2009.

- ^ Icons of Hip Hop. Hess (2007), pp. 360.

- ^ Illmatic: Ten-Year Anniversary Series Review on Blender Archived May 3, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Maxim Digital. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Sloppy Joe. Review of Illmatic Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. MSU. Retrieved on March 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Discogs.com – Nas – Illmatic Archived September 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Discogs. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- ^ a b 19 Tributes & Parodies of Nas' Illmatic Album Cover Archived May 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Ego Trip. Retrieved on May 21, 2013.

- ^ "Nas Reveals Inspiration Behind "Illmatic" Album Cover". ballerstatus.com. February 6, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ ByronCrawford.com: Illmatic vs. New Miserable Experience Archived September 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Byron Crawford. Retrieved on February 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Marriott, Rob. 10 Ways Nas' "Illmatic" Changed Hip-Hop Archived May 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Complex. Retrieved on 2013-05-20.

- ^ a b XXLmag.com – » The Carter III > Illmatic Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. XXL. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Raekwon. "Shark Niggas (Biters)", Only Built 4 Cuban Linx..., Loud, 1995. See also: Nas. "Last Real Nigga Alive", God's Son, Columbia, 2002.

- ^ Discogs.com – Nas – Illmatic (FR) Archived January 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Discogs. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- ^ Discogs.com – Nas – Illmatic (NE) Archived January 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Discogs. Retrieved on August 10, 2008

- ^ Discogs.com – Nas – Illmatic (CA) Archived September 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Discogs. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- ^ Discogs.com – Nas – Illmatic (UK) Archived January 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Discogs. Retrieved on August 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Basham, David. Got Charts? Nas Lookin' To Grow Legs; Jay-Z Unplugs Archived September 12, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. MTV News. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ allmusic ((( Illmatic > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles ))). All Media Guide, LLC. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hip Hop Album Sales: Week Ending 04/20/2014". Hip Hop DX. April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Certification – April 2002". Canadian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Dimitri (April 22, 1994). "Illmatic". Entertainment Weekly. No. 219. New York. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Siegmund, Heidi (May 22, 1994). "Nas, 'illmatic,' Columbia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b McCann, Ian (July 9, 1994). "Nas – Illmatic". NME. London. p. 44. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Touré (August 25, 1994). "Illmatic". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on March 31, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Shortie (April 1994). "Nas: Illmatic". The Source. No. 55. New York. p. 73. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Jones, James T. IV (May 10, 1994). "Rapper NAS mines his gritty life for eloquent 'Illmatic'". USA Today. McLean. Life section, p. 10.D. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Curtis 2010, p. 417.

- ^ Abramovich, Alex (December 5, 2004). "Hip-Hop Family Values". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (June 1994). "Reviews". Playboy. Chicago. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Osorio, Kim (May 14, 2012). "5 Mics: Who Got Next?". The Source. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c "The Greatest Story Never Told". Archived from the original on January 31, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). HipHopDX. Retrieved on January 20, 2007. - ^ a b Gasteier, Matthew Nas's Illmatic 2009 pp. 52–54.

- ^ Reginald C. Dennis Death Of a Dynasty Archived June 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. HipHopdx.com

- ^ "Reviews for Illmatic XX [20th Anniversary Edition] by Nas". Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 11, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (June 15, 2022). "Xgau Sez: June, 2022". And It Don't Stop. Substack. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Gabriel, Robert (May 7, 2004). "Nas: Illmatic 10th Anniversary Platinum Edition (Columbia)". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Josephs, Brian (April 21, 2014). "Nas – Illmatic XX". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Nas". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ "Nas: Illmatic". Mojo. London. 2004. p. 103. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Weiss, Jeff (January 23, 2013). "Nas: Illmatic". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Nas: Illmatic". Q. No. 334. London. May 2014. p. 125.

- ^ a b Ryan 2004, pp. 568–69.

- ^ a b "Retrospective: XXL Albums". XXL. No. 98. New York. December 2007.

- ^ a b "The Greatest Hip-Hop Albums of all Time". Rap.about.com. April 11, 2014. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Illmatic: The Best Hip Hop Album of All Time Archived July 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Hip Hop Blogs. Retrieved on August 31, 2008.

- ^ Pareles, Jon. The Week Ahead: May 14 – May 20; Pop/Jazz Archived June 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved on March 20, 2009.

- ^ Henderson (2002), p. 133.

- ^ Leeds, Jeff. Rapper Nas Is to Join Label Led by Former Rival Jay-Z Archived June 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved on March 20, 2009.

- ^ Sanneh, Kelefa. Nas Writes Hip-Hop's Obituary Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved on March 20, 2009.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (June 18, 2013). "Nas/The Roots". MSN Music. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ Goldstein, Hartley (November 17, 2003). Top 100 Albums of the 1990s Archived May 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Pitchfork. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ Rolling Stone Lists: The Essential Recordings of the '90s Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Rocklist. Retrieved on March 15, 2009.

- ^ a b The Critics Top 100 Black Music Albums of All Time Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. TrevorNelson.com. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Vinyl.com: Illmatic Archived February 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Vinyl. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ The Greatest Hip Hop Albums Of All Time Archived December 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ a b The Source: 100 Best Rap Albums Archived August 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Rocklist. Retrieved on February 22, 2009.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: Illmatic – Nas". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Illmatic [10th Anniversary Platinum Edition] – Nas". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- ^ Village Voice, The (February 19, 2014). "The 50 Most New York City Albums Ever". Village Voice. New York City. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Jackson and Kermit the Frog Added to National Recording Registry". The New York Times. March 24, 2021. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Nas & Rakim: Meeting of The Kings Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ Gloden, Gabe. I Love 1994 Archived February 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Stylus Magazine. Retrieved on 2013-04-11.

- ^ Reeves, Mosi. Is New York hip-hop dead? Archived October 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Creative Loafing. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. Nighttime is More Trife Than Ever Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 255–60.

- ^ Weiss, Jeff. "Illmatic Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Kangas, Chaz. "Nas' 'Illmatic' at 30: A classic album still in a class of its own". The Current. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Biography: Nas Archived March 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric., and Sohail Daulatzai. "Born Alone, Die Alone." Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic., pp. 2010. 241–43.

- ^ Vasquez, Andres Ghostface Killah Says "Illmatic" Made Him "Step His Pen Game Up" Archived April 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine HipHopDX Retrieved June 16, 2013

- ^ Lily, Mercer SB.TV Interview – Elzhi Archived May 5, 2013, at archive.today SB.TV Retrieved April 14, 2013

- ^ Kweli, Talib My Top 100 Hip Hop Albums Archived September 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine talibkweli.tumblr.com Retrieved on March 8, 2013.

- ^ Fiasco, Lupe Lupe Fiasco Talks About Nas On OK Player Archived June 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine thelupendblog.com Retrieved on March 8, 2013.

- ^ New Saigon & Just Interview – Speak on Amerikaz Most, Illmatic, Wu & 50 cent slumz.boxden.com Retrieved on March 8, 2013.

- ^ Sampling Soul: 9th Wonder On Illmatic Archived April 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on March 9, 2013.

- ^ "#10. Nas, Illmatic (1994) — Wiz Khalifa's 25 Favorite Rap Albums". Complex. March 29, 2011. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Keys, Alicia Alicia Key's 25 Favorite Rap Albums Archived December 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Complex.com Retrieved on March 8, 2013.

- ^ The Game. "Hustlers", The Documentary, Interscope, 2005.

- ^ Reid, Shaheem. Mixtape Mondays: Chronicles of Junior Mafia Archived October 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ Diaz, Ruben. 5 Minutes With Common[permanent dead link]. BallerStatus. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ UniversalUrban: Common Archived July 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. umusic.ca. Retrieved on January 20, 2007.

- ^ Hale, Andreas The Brilliance Of Kendrick Lamar, Illmatic Comparisons And The Fear Giving Classic Ratings Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 8, 2013

- ^ Murray, Keith IS KENDRICK LAMAR'S 'GOOD KID, M.A.A.D CITY' THE MOST IMPORTANT DEBUT SINCE 'ILLMATIC'? Archived March 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 8, 2013

- ^ Porco, Alessandro "Time is Illmatic": A Critical Retrospective on Nas's Groundbreaking Debut Archived April 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine SUNY Buffalo Retrieved April 12, 2013

- ^ Sputnikmusic: Staff Review – It Was Written. Sputnikmusic.com. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Ortiz, Edwin (February 4, 2014). "Nas Preps "Illmatic XX" 20th Anniversary Edition, Plans to Perform Whole Album on Tour". Complex Music. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- ^ Kennedy, Gerrick D. (February 8, 2014). "Nas to mark 20th anniversary of 'Illmatic' with reissue, film, tour". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ "Oricon Top 50 Albums: 1994-04-19" (in Japanese). Oricon. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Nas Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Nas Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Nas – Illmatic XX" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Nas – Illmatic XX". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Official R&B Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Nas Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "Nas – Chart History: R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog Albums". Billboard. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "Official IFPI Charts – Top-75 Albums Sales Chart (Combined) – Εβδομάδα: 46/2024". IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Nas – Illmatic XX" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 1994". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 6, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Nas – Illmatic". Music Canada.

- ^ "British album certifications – Nas – Illmatic". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – Nas – Illmatic". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "Best Rap Albums of 1994". Rap.about.com. October 14, 2006. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ "Top 10 Essential Hip-Hop Albums – 10 Essential Rap/Hip-Hop Albums". Rap.about.com. April 9, 2014. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Blender. Dennis Publishing. April 2003. ISBN 233667062986.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ MTV.com: List – #2 Illmatic Archived December 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ "Apple Music 100 Best Albums". Apple Music 100 Best Albums. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Moon, Tom. 1000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die Archived February 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Tom Moon. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". NME. October 25, 2013. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

184. ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020 Retrieved November 13, 2020

Bibliography

[edit]- Curtis, Edward E. (2010). Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-3040-8.

- Torgoff, Martin (2004). Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945–2000. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5863-0.

- Oliver Wang, Dante Ross (2003). Classic Material: The Hip-Hop Album Guide. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-561-8.

- Michael Eric Dyson, Sohail Daulatzai (2010). Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas's Illmatic. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00211-5.

- Cobb, William Jelani (2006). To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1670-9.

- Henderson, Ashyia N. (2008). Contemporary Black Biography: Profiles from the International Black Community. Vol. 33. Gale Research International. ISBN 978-0-7876-5914-1.

- Jenkins, Sacha; et al. (December 1999). Ego Trip's Book of Rap Lists. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 352. ISBN 0-312-24298-0.

- Hess, Mickey (2007). Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. Edition: illustrated. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33904-2. ISBN 0-313-33902-3

- Boyd, Todd (2004). The New H.N.I.C.: The Death of Civil Rights and the Reign of Hip Hop. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-9896-9.

- Ryan, Chris (2004). "Nas". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Kool Moe Dee; Chuck D (November 2003). There's a God on the Mic. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-533-1.

- Light, Alan; et al. (October 1999). The Vibe History of Hip Hop. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80503-7.

External links

[edit]- Illmatic at Discogs (list of releases)

- Illmatic at MusicBrainz (list of releases)

- 1994 debut albums