The Dream Shall Never Die

| Date | August 12, 1980 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 32 minutes |

| Venue | Madison Square Garden |

| Location | New York City |

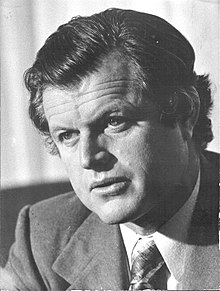

"The Dream Shall Never Die" was a speech delivered by U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy during the 1980 Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden, New York City. In his address, Kennedy defended post-World War II liberalism, advocated for a national healthcare insurance model, criticized Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan, and implicitly rebuked incumbent president Jimmy Carter for his more moderate political stances. It has been remembered by some as Kennedy's best speech, and is one of the most memorable political speeches in modern American history.

Background

[edit]

August 12 was devoted to platform debate. It began in the morning with social issues, and contentiously shifted to economic policies. Both the Carter delegate majority and the Kennedy delegate minority had six speakers to propose policies and counter the others' arguments. The final majority spokesman was United States Ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young, whose words were drowned out by increasingly intense pro-Kennedy chants, which did not stop until Representative Barbara Mikulski introduced Kennedy, who himself was to make the minority's final economic comments.[1]

The speech

[edit]Composition

[edit]According to Bernard K. Duffy and Richard Leeman, the first draft of the speech was created by Carey Parker and Bob Shrum. Kennedy made additions, which were taken by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Ted Sorensen and made into the final draft. Kennedy rehearsed the speech with a teleprompter twice, once in his hotel and again at the convention site.[2]

Kennedy remembered the process somewhat differently, stating in a 2005 interview that the original speech was continuously altered, starting from before the convention when Carter declined to participate in a debate and instead suggested that differences be expressed during the platform committees. That night Kennedy and his sisters Jean, Pat, and Eunice began piecing together a new speech, with Shrum filling in where necessary. This supposedly continued every night until the platform arguments.[3]

Summary

[edit]Kennedy spoke for thirty-two minutes.[4] He opened his speech by conceding the end of his presidential campaign:[5]

Well, things worked out a little different from the way I thought, but let me tell you, I still love New York!

Kennedy criticized Ronald Reagan's ideas and nostalgically appealed to a defense of old liberal values:[6][7]

The great adventures which our opponents offer is a voyage into the past. Progress is our heritage, not theirs. What is right for us as Democrats is also the right way for Democrats to win. The commitment I seek is not to outworn views but to old values that will never wear out. Programs may sometimes become obsolete, but the ideal of fairness always endures. Circumstances may change, but the work of compassion must continue. It is surely correct that we cannot solve problems by throwing money at them, but it is also correct that we dare not throw out our national problems onto a scrap heap of inattention and indifference. The poor may be out of political fashion, but they are not without human needs. The middle class may be angry, but they have not lost the dream that all Americans can advance together.

Kennedy later developed his argument by displaying his role as a spokesperson for Democratic voters. To do this, he employed prosopopoeia, telling real life stories of people he had met while campaigning.[8] Shrum would maintain that this technique was new at the time and later popularized by Reagan:[5]

Among you, my golden friends across this land, I have listened and learned. I have listened to Kenny Dubois, a glassblower in Charleston, West Virginia, who has ten children to support but has lost his job after 35 years, just three years short of qualifying for his pension. I have listened to the Trachta family who farm in Iowa and who wonder whether they can pass the good life and the good earth on to their children. I have listened to the grandmother in East Oakland who no longer has a phone to call her grandchildren because she gave it up to pay the rent on her small apartment. I have listened to young workers out of work, to students without the tuition for college, and to families without the chance to own a home. I have seen the closed factories and the stalled assembly lines of Anderson, Indiana and South Gate, California, and I have seen too many, far too many idle men and women desperate to work. I have seen too many, far too many working families desperate to protect the value of their wages from the ravages of inflation.

Towards the end of the speech, Kennedy made his only mention of Carter in an unenthusiastic non-endorsement:[9]

I congratulate President Carter on his victory here. I am confident that the Democratic party will reunite on the basis of Democratic principles, and that together we will march towards a Democratic victory in 1980.

The crowd applauded and then fell silent. As Kennedy finished, he mentioned his two older brothers, John and Robert, something he usually avoided doing:[5]

And someday, long after this convention, long after the signs come down and the crowds stop cheering, and the bands stop playing, may it be said of our campaign that we kept the faith. May it be said of our Party in 1980 that we found our faith again. And may it be said of us, both in dark passages and in bright days, in the words of Tennyson that my brothers quoted and loved, and that have special meaning for me now:

I am a part of all that I have met

To [Though] much is taken, much abides

That which we are, we are–

One equal temper of heroic hearts

Strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.

Kennedy had been interrupted by cheers and applause a total of fifty-one times.[10] He would later write that the delegates' response was "warm and generous".[11] Sustained applause and cheers followed his speech for half an hour.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]The following day Carter told state and local officials during a reception at Sheraton Centre Hotel that "Last night after one of the greatest speeches I have ever heard I called Senator Kennedy and told him how much I appreciated it. Ours is a nation, ours is a party well-represented by thousands of people like you who believe in the greatness of the United States, and who believe in openness, debate, controversy, courage, conviction and who believe in their future, and are not afraid to express your will in the most open, democratic and greatest party on earth. I'm grateful to you for that."[13]

Reagan ended up defeating Carter in a landslide of 489 electoral votes to 49, or 50.7% to 41% of the popular vote.[14]

Legacy

[edit]The speech is considered the most famous of Kennedy's life and senatorial career and laid the foundation for the modern platform of the Democratic Party.[15] Schlesinger would write in his diary that he "had never heard Ted deliver a better speech."[10] Former campaign aide Joe Trippi later said, "In a lot of ways, a whole country of young people were inspired that day."[16] It is often considered to be one of the most effective political orations in modern American history.[17] Kennedy's speech was ranked as the 76th best American speech of the 20th century in a 1999 survey of academics.[18] According to Robert S. McElvaine, "It was a great speech to read or to hear in the arena, but it was considerably less effective on television."[19]

Kennedy also referenced his words during the endorsement he made for Barack Obama at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, saying, "the work begins anew, the hope rises again and the dream lives on".[10] Following Kennedy's death in 2009, many media outlets circulated footage of the closing remarks of his speech.[20]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Divided Democrats Renominate Carter". CQ Almanac. Washington DC: CQ Press. 1980.

- ^ Duffy & Leeman 2005, p. 245.

- ^ Craig, Bryan (July 25, 2016). "Ted Kennedy Remembers the 1980 Democratic Convention". Miller Center of Public Affairs. University of Virginia. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Burke 1992, p. 275.

- ^ a b c Shrum 2007, Chapter 3: Almost to the White House

- ^ Hersh 2010, p. 484.

- ^ Crines et al. 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Crines et al. 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Cost 2016

- ^ a b c Crines et al. 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Kennedy 2009, Chapter 18: Sailing Against the Wind.

- ^ Allis, Sam (February 18, 2009). "Losing a quest for the top, finding a new freedom". Boston Globe. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Hendrick (August 14, 1980). "Carter Wins Nomination for a Second Term; Gets Kennedy Pledge of Support and Work". The New York Times. New York City.

- ^ United States presidential election of 1980. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Senator Edward "Ted" Kennedy". U.S. Political Conventions & Campaigns. Northeastern University. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Wire, Sarah D. (August 26, 2008). "Warm welcome for party stalwart". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Vigil 2015, p. 1390.

- ^ Kuypers 2004, p. 185.

- ^ McElvaine 1988, p. 350.

- ^ Brooks, David (August 29, 2009). "Kennedy the great compromiser". The San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego, California: Copley Press. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

References

[edit]- Burke, Richard E. (1992). The Senator: My Ten Years With Ted Kennedy. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-09134-6.

- Cost, Jay (July 21, 2016). "Ted Cruz, Ted Kennedy, and 'The Dream Will Never Die'". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- Crines, Andrew S.; Moon, David S.; Lehrman, Robert; Thody, Philip, eds. (2016). Democratic Orators from JFK to Barack Obama. Rhetoric, Politics and Society (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 9781137509031.

- Duffy, Bernard K.; Leeman, Richard W. (2005). American Voices: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Orators. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313327902.

- Hersh, Burton (2010). Edward Kennedy: An Intimate Biography (illustrated ed.). Counterpoint Press. ISBN 9781582436289.

- McElvaine, Robert S. (1988). Mario Cuomo: A Biography (illustrated ed.). Scribner's. ISBN 9780684189703.

- Kennedy, Edward M. (2009). True Compass. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 9780446564212.

- Kuypers, Jim A., ed. (2004). The Art of Rhetorical Criticism. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205371419.

- Shrum, Robert (2007). No Excuses: Concessions of a Serial Campaigner. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416545583.

- Vigil, Tammy R. (2015). Connecting with Constituents: Identification Building and Blocking in Contemporary National Convention Addresses. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739199046.