Taurine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Aminoethanesulfonic acid | |

| Other names

Tauric acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.168 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C2H7NO3S | |

| Molar mass | 125.14 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless or white solid |

| Density | 1.734 g/cm3 (at −173.15 °C) |

| Melting point | 305.11 °C (581.20 °F; 578.26 K) Decomposes into simple molecules |

| Acidity (pKa) | <0, 9.06 |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Sulfamic acid Aminomethanesulfonic acid Homotaurine |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Taurine (/ˈtɔːriːn/), or 2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, is a non-proteinogenic naturally occurring amino sulfonic acid that is widely distributed in animal tissues.[1] It is a major constituent of bile and can be found in the large intestine, and accounts for up to 0.1% of total human body weight.

Taurine is named after Latin taurus (cognate to Ancient Greek ταῦρος, taûros) meaning bull or ox, as it was first isolated from ox bile in 1827 by German scientists Friedrich Tiedemann and Leopold Gmelin.[2] It was discovered in human bile in 1846 by Edmund Ronalds.[3]

Although taurine is abundant in human organs with diverse putative roles, it is not an essential human dietary nutrient and is not included among nutrients with a recommended intake level.[4] Taurine is synthesized naturally in the human liver from methionine and cysteine.[5]

Taurine is commonly sold as a dietary supplement, but there is no good clinical evidence that taurine supplements provide any benefit to human health.[6] Taurine is used as a food additive for cats (who require it as an essential nutrient), dogs, and poultry.[7]

Taurine concentrations in land plants are low or undetectable, but up to 1000 nmol/g wet weight have been found in algae.[8][9]

Chemical and biochemical features

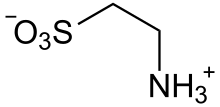

[edit]Taurine exists as a zwitterion H3N+CH2CH2SO−3, as verified by X-ray crystallography.[10] The sulfonic acid has a low pKa[11] ensuring that it is fully ionized to the sulfonate at the pHs found in the intestinal tract.

Synthesis

[edit]Synthetic taurine is obtained by the ammonolysis of isethionic acid (2-hydroxyethanesulfonic acid), which in turn is obtained from the reaction of ethylene oxide with aqueous sodium bisulfite. A direct approach involves the reaction of aziridine with sulfurous acid.[12]

In 1993, about 5000–6000 tonnes of taurine were produced for commercial purposes: 50% for pet food and 50% in pharmaceutical applications.[13] As of 2010, China alone has more than 40 manufacturers of taurine. Most of these enterprises employ the ethanolamine method to produce a total annual production of about 3000 tonnes.[14]

In the laboratory, taurine can be produced by alkylation of ammonia with bromoethanesulfonate salts.[15]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Taurine is naturally derived from cysteine. Mammalian taurine synthesis occurs in the liver via the cysteine sulfinic acid pathway. In this pathway, cysteine is first oxidized to its sulfinic acid, catalyzed by the enzyme cysteine dioxygenase. Cysteine sulfinic acid, in turn, is decarboxylated by sulfinoalanine decarboxylase to form hypotaurine. Hypotaurine is enzymatically oxidized to yield taurine by hypotaurine dehydrogenase.[16]

Taurine is also produced by the transsulfuration pathway, which converts homocysteine into cystathionine. The cystathionine is then converted to hypotaurine by the sequential action of three enzymes: cystathionine gamma-lyase, cysteine dioxygenase, and cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase. Hypotaurine is then oxidized to taurine as described above.[17]

A pathway for taurine biosynthesis from serine and sulfate is reported in microalgae,[9] developing chicken embryos,[18] and chick liver.[19] Serine dehydratase converts serine to 2-aminoacrylate, which is converted to cysteic acid by 3′-phosphoadenylyl sulfate:2-aminoacrylate C-sulfotransferase. Cysteic acid is converted to taurine by cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase.

In food

[edit]Taurine occurs naturally in fish and meat.[6][20][21] The mean daily intake from omnivore diets was determined to be around 58 mg (range 9–372 mg),[22] and to be low or negligible from a vegan diet.[6] Typical taurine consumption in the American diet is about 123–178 mg per day.[6]

Taurine is partially destroyed by heat in processes such as baking and boiling. This is a concern for cat food, as cats have a dietary requirement for taurine and can easily become deficient. Either raw feeding or supplementing taurine can satisfy this requirement.[23][24]

Both lysine and taurine can mask the metallic flavor of potassium chloride, a salt substitute.[25]

Breast milk

[edit]Prematurely born infants are believed to lack the enzymes needed to convert cystathionine to cysteine, and may, therefore, become deficient in taurine. Taurine is present in breast milk, and has been added to many infant formulas as a measure of prudence since the early 1980s. However, this practice has never been rigorously studied, and as such it has yet to be proven to be necessary, or even beneficial.[26]

Energy drinks and dietary supplements

[edit]Taurine is an ingredient in some energy drinks in amounts of 1–3 g per serving.[6][27][28][29] A 1999 assessment of European consumption of energy drinks found that taurine intake was 40–400 mg per day.[22][clarification needed]

Research

[edit]Taurine is not regarded as an essential human dietary nutrient and has not been assigned recommended intake levels.[4] High-quality clinical studies to determine possible effects of taurine in the body or following dietary supplementation are absent from the literature.[6] Preliminary human studies on the possible effects of taurine supplementation have been inadequate due to low subject numbers, inconsistent designs, and variable doses.[6] Preliminary studies have suggested that supplementing with taurine may increase exercise capacity[30][31][32] and affects lipid profiles in individuals with diabetes.[33][34]

Safety and toxicity

[edit]According to the European Food Safety Authority, taurine is "considered to be a skin and eye irritant and skin sensitiser, and to be hazardous if inhaled;" it may be safe to consume up to 6 grams of taurine per day.[7] Other sources indicate that taurine is safe for supplemental intake in normal healthy adults at up to 3 grams per day.[6][35]

A 2008 review found no documented reports of negative or positive health effects associated with the amount of taurine used in energy drinks, concluding, "The amounts of guarana, taurine, and ginseng found in popular energy drinks are far below the amounts expected to deliver either therapeutic benefits or adverse events".[36]

Animal dietary requirement

[edit]Cats

[edit]Cats lack the enzymatic machinery (sulfinoalanine decarboxylase) to produce taurine and must therefore acquire it from their diet.[37] A taurine deficiency in cats can lead to retinal degeneration and eventually blindness – a condition known as central retinal degeneration[38][39] as well as hair loss and tooth decay. Other effects of a diet lacking in this essential amino acid are dilated cardiomyopathy[40], and reproductive failure in female cats[citation needed].

Decreased plasma taurine concentration has been demonstrated to be associated with feline dilated cardiomyopathy. Unlike CRD, the condition is reversible with supplementation.[41]

Taurine is now a requirement of the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) and any dry or wet food product labeled approved by the AAFCO should have a minimum of 0.1% taurine in dry food and 0.2% in wet food.[42] Studies suggest the amino acid should be supplied at 10 mg per kilogram of bodyweight per day for domestic cats.[43]

Other mammals

[edit]A number of other mammals also have a requirement for taurine. While the majority of dogs can synthesize taurine, case reports have described a singular American cocker spaniel, 19 Newfoundland dogs, and a family of golden retrievers suffering from taurine deficiency treatable with supplementation. Foxes on fur farms also appear to require dietary taurine. The rhesus, cebus and cynomolgus monkeys each require taurine at least in infancy. The giant anteater also requires taurine.[44]

Birds

[edit]Taurine appears to be essential for the development of passerine birds. Many passerines seek out taurine-rich spiders to feed their young, particularly just after hatching. Researchers compared the behaviours and development of birds fed a taurine-supplemented diet to a control diet and found the juveniles fed taurine-rich diets as neonates were much larger risk takers and more adept at spatial learning tasks. Under natural conditions, each blue tit nestling receive 1 mg of taurine per day from parents.[45]

Taurine can be synthesized by chickens. Supplementation has no effect on chickens raised under adequate lab conditions, but seems to help with growth under stresses such as heat and dense housing.[46]

Fish

[edit]Species of fish, mostly carnivorous ones, show reduced growth and survival when the fish-based feed in their food is replaced with soy meal or feather meal. Taurine has been identified as the factor responsible for this phenomenon; supplementation of taurine to plant-based fish feed reverses these effects. Future aquaculture is expected to use more of these more environmentally-friendly protein sources, so supplementation would become more important.[47]

The need of taurine in fish is conditional, differing by species and growth stage. The Olive flounder, for example, has lower capacity to synthesize taurine compared to the rainbow trout. Juvenile fish are less efficient at taurine biosyntheis due to reduced cysteine sulfinate decarboxylase levels.[48]

Derivatives

[edit]- Taurine is used in the preparation of the anthelmintic drug netobimin (Totabin).

- Taurolidine

- Taurocholic acid and tauroselcholic acid

- Tauromustine

- 5-Taurinomethyluridine and 5-taurinomethyl-2-thiouridine are modified uridines in (human) mitochondrial tRNA.[49]

- Tauryl is the functional group attaching at the sulfur, 2-aminoethylsulfonyl.[50]

- Taurino is the functional group attaching at the nitrogen, 2-sulfoethylamino.

- Thiotaurine

- Peroxytaurine which is a degradation product by both superoxide and heat degradation.

See also

[edit]- Homotaurine (tramiprosate), precursor to acamprosate

- Taurates, a group of surfactants

References

[edit]- ^ Schuller-Levis GB, Park E (September 2003). "Taurine: new implications for an old amino acid". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 226 (2): 195–202. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00611-6. PMID 14553911.

- ^ Tiedemann F, Gmelin L (1827). "Einige neue Bestandtheile der Galle des Ochsen". Annalen der Physik. 85 (2): 326–337. Bibcode:1827AnP....85..326T. doi:10.1002/andp.18270850214.

- ^ Ronalds BF (2019). "Bringing Together Academic and Industrial Chemistry: Edmund Ronald' Contribution". Substantia. 3 (1): 139–152.

- ^ a b "Daily Value on the New Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". US Food and Drug Administration. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Taurine". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 25 May 2024. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Taurine". Drugs.com. 15 May 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ a b EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (2012). "Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy of taurine as a feed additive for all animal species". EFSA Journal. 10 (6): 2736. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2736.

- ^ Kataoka H, Ohnishi N (1986). "Occurrence of Taurine in Plants". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 50 (7): 1887–1888. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.50.1887.

- ^ a b McCusker S, Buff PR, Yu Z, Fascetti AJ (2014). "Amino acid content of selected plant, algae and insect species: a search for alternative protein sources for use in pet foods". Journal of Nutritional Science. 3: e39. doi:10.1017/jns.2014.33. ISSN 2048-6790. PMC 4473169. PMID 26101608.

- ^ Görbitz CH, Prydz K, Ugland S (2000). "Taurine". Acta Crystallographica Section C. 56 (1): e23–e24. Bibcode:2000AcCrC..56E..23G. doi:10.1107/S0108270199016029.

- ^ Irving CS, Hammer BE, Danyluk SS, Klein PD (October 1980). "13C nuclear magnetic resonance study of the complexation of calcium by taurine". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 13 (2): 137–150. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(00)80117-8. PMID 7431022.

- ^ Kosswig K (2000). "Sulfonic Acids, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_503. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Tully PS, ed. (2000). "Sulfonic Acids". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1921120620211212.a01. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ Amanda Xia (2010-01-03). "China Taurine Market Is Expected To Recover". Press release and article directory: technology. Archived from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Marvel CS, Bailey CF, Cortese F (1938). "Taurine". Organic Syntheses. 18: 77. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.018.0077.

- ^ Sumizu K (September 1962). "Oxidation of hypotaurine in rat liver". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 63: 210–212. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(62)90357-8. PMID 13979247.

- ^ Ripps H, Shen W (2012). "Review: taurine: a "very essential" amino acid". Molecular Vision. 18: 2673–2686. PMC 3501277. PMID 23170060.

- ^ Machlin LJ, Pearson PB, Denton CA (1955). "The Utilization of Sulfate Sulfur for the Synthesis of Taurine in the Developing Chick Embryo". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 212 (1): 469–475. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)71134-4. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 13233249.

- ^ Sass NL, Martin WG (1972-03-01). "The Synthesis of Taurine from Sulfate III. Further Evidence for the Enzymatic Pathway in Chick Liver". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 139 (3): 755–761. doi:10.3181/00379727-139-36232. ISSN 1535-3702. PMID 5023763. S2CID 77903.

- ^ Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME (June 2006). "The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (6 Suppl): 1636S–1640S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.6.1636S. PMID 16702333.

- ^ Huxtable RJ (January 1992). "Physiological actions of taurine". Physiological Reviews. 72 (1): 101–163. doi:10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. PMID 1731369. S2CID 27844955.

- ^ a b "Opinion on Caffeine, Taurine and D-Glucurono –γ-Lactone as constituents of so-called 'energy' drinks". Directorate-General Health and Consumers, European Commission, European Union. 1999-01-21. Archived from the original on 2006-06-23.

- ^ Jacobson SG, Kemp CM, Borruat FX, Chaitin MH, Faulkner DJ (October 1987). "Rhodopsin topography and rod-mediated function in cats with the retinal degeneration of taurine deficiency". Experimental Eye Research. 45 (4): 481–490. doi:10.1016/S0014-4835(87)80059-3. PMID 3428381.

- ^ Spitze AR, Wong DL, Rogers QR, Fascetti AJ (2003). "Taurine concentrations in animal feed ingredients; cooking influences taurine content" (PDF). Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 87 (7–8): 251–262. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0396.2003.00434.x. PMID 12864905. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ dos Santos BA, Campagnol PC, Morgano MA, Pollonio MA (January 2014). "Monosodium glutamate, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, lysine and taurine improve the sensory quality of fermented cooked sausages with 50% and 75% replacement of NaCl with KCl". Meat Science. 96 (1): 509–513. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.08.024. PMID 24008059.

- ^ Heird WC (November 2004). "Taurine in neonatal nutrition – revisited". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 89 (6): F473–F474. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.055095. PMC 1721777. PMID 15499132.

- ^ "Original Rockstar Ingredients". rockstar69.com. Archived from the original on 2007-11-03. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ Chang PL (2008-05-03). "Nos Energy Drink – Review". energyfanatics.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Kurtz JA, VanDusseldorp TA, Doyle JA, Otis, JS (2021). "Taurine in sports and exercise". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18 (39): 39. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00438-0. PMC 8152067. PMID 34039357.

- ^ Zhang M (2003). "Role of taurine supplementation to prevent exercise-induced oxidative stress in healthy young men". Amino Acids. 26: 203–207. PMID 15042451.

- ^ Beyranvand M (2011). "Effect of taurine supplementation on exercise capacity of patients with heart failure". Journal of Cardiology. 57 (3): 333–337. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.01.007. PMID 21334852.

- ^ Silva L (2013). "Effects of taurine supplementation following eccentric exercise in young adults". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 39 (1): 101–104. doi:10.1139/apnm-2012-0229. PMID 24383513.

- ^ Franconi F (1995). "Plasma and platelet taurine are reduced in subjects with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: effects of taurine supplementation". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 61 (5): 1115–1119. doi:10.1093/ajcn/61.5.1115. PMID 7733037.

- ^ Mizushima S (1996). "Effects of Oral Taurine Supplementation on Lipids and Sympathetic Nerve Tone". In Huxtable R (ed.). Taurine 2: Basic and Clinical Aspects (1 ed.). NY: Springer New York. pp. 615–622.

- ^ Shao A, Hathcock JN (April 2008). "Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, L-glutamine and L-arginine". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 50 (3): 376–399. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.01.004. PMID 18325648.

the newer method described as the Observed Safe Level (OSL) or Highest Observed Intake (HOI) was utilized. The OSL risk assessments indicate that based on the available published human clinical trial data, the evidence for the absence of adverse effects is strong for taurine at supplemental intakes up to 3 g/day, glutamine at intakes up to 14 g/day and arginine at intakes up to 20 g/day, and these levels are identified as the respective OSLs for normal healthy adults.

- ^ Clauson KA, Shields KM, McQueen CE, Persad N (2008). "Safety issues associated with commercially available energy drinks". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 48 (3): e55–e67. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07055. PMID 18595815. S2CID 207262028.

- ^ Knopf K, Sturman JA, Armstrong M, Hayes KC (May 1978). "Taurine: an essential nutrient for the cat". The Journal of Nutrition. 108 (5): 773–778. doi:10.1093/jn/108.5.773. PMID 641594.

- ^ Hayes KC, Carey RE, Schmidt SY (1975). "Retinal Degeneration Associated with Taurine Deficiency in the Cat". Science. 188 (4191): 949–951. Bibcode:1975Sci...188..949H. doi:10.1126/science.1138364. PMID 1138364.

- ^ Nutrient Requirements of Cats, Revised Edition. Board On Agriculture. 1986. ISBN 978-0-309-07483-4.

- ^ Hayes KC, Carey RE, Schmidt SY (May 1975). "Retinal degeneration associated with taurine deficiency in the cat". Science. 188 (4191): 949–951. Bibcode:1975Sci...188..949H. doi:10.1126/science.1138364. PMID 1138364.

- ^ Pion PD, Kittleson MD, Rogers QR, Morris JG (August 1987). "Myocardial failure in cats associated with low plasma taurine: a reversible cardiomyopathy". Science. 237 (4816): 764–768. Bibcode:1987Sci...237..764P. doi:10.1126/science.3616607. PMID 3616607.

- ^ "AAFCO Cat Food Nutrient Profiles". Archived from the original on 2015-05-29. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ Burger IH, Barnett KC (1982). "The taurine requirement of the adult cat". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 23 (9): 533–537. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1982.tb02514.x.

- ^ Schaffer SW, Ito T, Azuma J (January 2014). "Clinical significance of taurine". Amino Acids. 46 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1007/s00726-013-1632-8. PMID 24337931. (abstracts of animal citations used to provide list of species)

- ^ Arnold KE, Ramsay SL, Donaldson C, Adam A (October 2007). "Parental prey selection affects risk-taking behaviour and spatial learning in avian offspring". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1625): 2563–2569. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0687. PMC 2275882. PMID 17698490.

- ^ Surai P, Kochish I, Kidd M (February 2020). "Taurine in poultry nutrition". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 260: 114339. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114339. S2CID 209599794.

- ^ Salze GP, Davis DA (February 2015). "Taurine: a critical nutrient for future fish feeds". Aquaculture. 437: 215–229. Bibcode:2015Aquac.437..215S. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.12.006.

- ^ Sampath WW, Rathnayake RM, Yang M, Zhang W, Mai K (November 2020). "Roles of dietary taurine in fish nutrition". Marine Life Science & Technology. 2 (4): 360–375. Bibcode:2020MLST....2..360S. doi:10.1007/s42995-020-00051-1.

- ^ Suzuki T, Suzuki T, Wada T, Saigo K, Watanabe K (December 2002). "Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: new insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases". The EMBO Journal. 21 (23): 6581–6589. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf656. PMC 136959. PMID 12456664.

- ^ Bünzli-Trepp U (2007). Systematic nomenclature of organic, organometallic and coordination chemistry. EPFL Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4200-4615-1.