Stuart London

| Stuart London | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1603–1714 | |||

Map of London c.1690, after Wenceslaus Hollar | |||

| Location | London | ||

| Monarch(s) | James VI and I, Charles I of England, Charles II of England, James II of England, William III of England and Mary II of England, Anne, Queen of Great Britain | ||

| Leader(s) | Oliver Cromwell, Richard Cromwell | ||

| Key events | English Civil War, Great Plague of London, Great Fire of London | ||

Chronology

| |||

| History of London |

|---|

| See also |

|

|

The Stuart period in London began with the reign of James VI and I in 1603 and ended with the death of Queen Anne in 1714. London grew massively in population during this period, from about 200,000 in 1600 to over 575,000 by 1700, and in physical size, sprawling outside its city walls to encompass previously outlying districts such as Shoreditch, Clerkenwell, and Westminster. The city suffered several large periods of devastation, including the English Civil War and the Great Fire of London, but new areas were built from scratch in what had previously been countryside, such as Covent Garden, Bloomsbury, and St. James's, and the City was rebuilt after the Fire by architects such as Christopher Wren.

London was also struck by waves of disease during this time, most notably the Great Plague in 1665.The period saw several attempts to enforce uniformity of worship from Catholics, Anglicans and Puritans. Both Catholics and Nonconformist Protestants were persecuted during this period. This resulted in some of the most famous conflicts and uprisings of the period, such as the Catholic-led Gunpowder Plot, the anti-Catholic Popish Plot, and the ousting of the Catholic king, James II, in favour of the Protestant William III in the Glorious Revolution. Capital and corporal punishment was often used as a penalty for crimes, with Tyburn being a popular location for hangings.

London's trade began to develop into a modern economy, with the founding of the Bank of England in 1694, and the early development of the stock market and insurance markets such as Lloyd's of London. London's merchants often met in the newly-introduced coffeehouses, and the city became the hub of an emerging global empire, with the headquarters of colonial institutions such as the East India Company.

London saw a flourishing of literature, philosophy, theatre and art during this time, as the home of writers and artists such as William Shakespeare, John Milton, John Dryden, John Bunyan, Aphra Behn, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Lely, Peter Paul Rubens, and Grinling Gibbons. The first English opera, The Siege of Rhodes, was produced in London in 1656. The city was home to important scientists such as William Harvey, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton, John Flamsteed, and Edmond Halley.

Demography

[edit]London experienced massive population growth during this period. In 1600, London's population was about 200,000.[1] By 1650 it was about 375,000, and by 1700 it was 575,000, making it by far the largest city in England throughout the period.[2][1][3] Between 1670-1700, its population was 420% greater than the next ten largest places in England put together.[4] The average height for male Londoners was 5'7½" (172 cm) and the average height for female Londoners was 5'2¼" (158cm).[5]

In 1639, the number of foreigners living in Westminster and the City was estimated at 1,688- mostly French and Dutch, with some Belgians, Italians, Spaniards, Germans, and Poles.[6] A number of Greek Christian refugees arrived in London in the 1670s fleeing persecution from the Ottoman Empire, and were permitted to build their own church.[7] London had some inhabitants from Turkey, who brought new businesses such as London's first coffeeshop and its first Turkish bath.[8] After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, thousands of French Protestants called Huguenots fled to Britain, many coming to London, and in particular, Spitalfields. In 1697, there were 22 French Protestant churches in London.[9] Dutch, Italian, and Danish communities were also permitted to establish their own churches.[9][10] Thanks in part to immigrant communities, the population of the East End increased over 400% in this period, from 21,000 in 1600 to 91,000 in 1700.[11] Short-term visitors arrived in London from further afield. In 1616, the Native American woman Pocahontas and her son Thomas Rolfe arrived from Virginia;[12] in 1682, two ambassadors arrived from Banten in Indonesia called Kyayi Ngabehi Naya Wipraja and Kyayi Ngabehi Jaya Seidana;[13] and in 1698, the Russian tsar Peter the Great stayed in Sayes Court in Deptford for four months.[14]

Although Jewish people were officially forbidden from living in England at the beginning of the period, there was a small group of Jewish families from Portugal and Spain living in London, outwardly professing to have converted to Catholicism.[15] This group included the merchant Antonio Fernandez Carvajal.[15] In 1656, the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell made it known that he would no longer enforce the ban, and invited Jews to return.[15] The first synagogue of this period was built in 1657 on Creechurch Lane,[16] the first Jewish burial ground opened in the same year on Mile End Road,[17] and Bevis Marks synagogue was built 1700-1701.[18] In 1660, there were about 35 Jewish families, mostly Polish and German, living in the East End.[19]

There were small numbers of black people living in London during this period, mostly enslaved people working in the houses of people who owned plantations in the Caribbean, and freed domestic servants.[20] Charles II bought a black pageboy, and in 1662, Lord Sandwich bought "a little Turk and a negro" for his daughters.[21] The diarist Samuel Pepys had a black kitchen maid, and the naval officer William Batten had a black manservant called Mingo.[21] In 1684, the Barbados planter Robert Rich brought an enslaved woman called Katherine Auker to his house in London. She was mistreated and thrown out onto the streets, where she was imprisoned for vagrancy. Rich and his wife then returned to Barbados, leaving Auker imprisoned. She petitioned to be discharged from his service, but the court only released her "until such time as the said Rich shall return from Barbados".[22]

Topography

[edit]In the Stuart period, the City of London was still surrounded by its Roman city wall on three sides, with the river Thames making the fourth side to the south.[23] However, the inhabited region expanded well beyond the bounds of the walls to Wapping in the east and Westminster in the west. Settlements that had previously been separate from London, like Shoreditch and Clerkenwell, began to be subsumed by London's sprawl.[24]

Ordinary houses were often built of wood, with each storey projecting out from the stories below, such that in some places, they almost touched over the road.[25] After 1662, main roads were required to have lanterns burning over the doors of houses until 9 p.m., an early form of street lighting.[26] Many of the landmarks in Stuart London dated from before the period, such as the Tower of London, London Stone, the Royal Exchange, Baynard's Castle, the Guildhall, and London Bridge.[27]

Building destruction

[edit]

Several of London's buildings suffered serious damage during the English Civil War and in the Interregnum period, as they were put to use by Parliament's army or destroyed for ideological reasons. Charing Cross was demolished in 1647.[29] St. Paul's Cathedral was in a state of disrepair throughout the first half of the period, having been struck by lightning in 1561. In 1648, soldiers from the New Model Army used it as a stable, smashing the stained glass, ripping up pews for firewood, and even baptising a foal in the font.[30] The removal of scaffolding caused sections of the roof to collapse, and slum houses were built against the outer walls.[30] Parliamentary soldiers rioted through the streets of London,[31] and destroyed the Salisbury Court Theatre.[32]

On Sunday, 2 September 1666 the Great Fire of London broke out at one o'clock in the morning at a house on Pudding Lane in the southern part of the City. Fanned by a southeasterly wind the fire spread quickly among the timber and thatched-roof buildings, which were primed to ignite after an unusually hot and dry summer.[33] Burning for several days, the Fire destroyed about 60% of the City, including Old St Paul's Cathedral, 87 parish churches, 44 livery company halls and the Royal Exchange. An estimated 13,200 houses were destroyed across 400 different streets and courts, leaving 100,000 people homeless. Huge camps of displaced Londoners formed around the City at Moorfields, St. George's Fields in Southwark, and to the north extending as far as Highgate.[34] Despite the destruction, the official death toll was only 4 people, likely an inaccurately low number.[35] Because of London's centrality as a port and financial center, the destruction of the fire affected the entire national economy. Losses were estimated at between £7 and £10 million according to contemporary estimates.[36]

Although the Great Fire is by far the most well-known, it was by no means the only fire to destroy large parts of London in this period. Fires destroyed Hungerford House in 1669; the Theatre Royal in 1672; 30 houses in Seething Lane, and about 100 in Shadwell in 1673; Goring House in 1674; 624 properties in Southwark in 1676; Montagu House in 1686; Bridgewater House in 1687; and the Palace of Whitehall in 1698.[37]

There were large storms which caused building damage in this period, including in 1662, 1678, and 1690.[38] In 1703, there was a hurricane which pulled the roofs off houses, toppled chimneys and church spires, pushed ships in the Thames from London Bridge down to Limehouse, and killed several people.[39]

New building work

[edit]

London's first new church since 1550 was the Queen's Chapel opposite St. James' Palace, built in the 1620s and designed by Inigo Jones.[40] Jones became the Surveyor to the King's Works in 1615, and so constructed several important new buildings in the first part of this period, such as the Queen's House in Greenwich and Banqueting House in Whitehall Palace.[40] Jones brought a new style of architecture to London, based on Italian Renaissance styles by Sebastiano Serlio and Andrea Palladio.[40] London's architects began to abandon the Gothic architecture style in favour of a classical one in this period.[41] However, some Gothic churches were still built, such as St. Mary Aldemary (c.1629) and St. Alban Wood Street (1633-34).[42] Towards the end of the period, Queen Anne's Bounty saw new churches built to cope with London's growth in population, including St. Anne's Limehouse, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor; and St. Paul's Deptford, designed by Thomas Archer.[43] The last church built in this period was St. John's Smith Square, also designed by Thomas Archer.[44]

During the English Civil War, Parliament's forces built forts around London to reinforce it against sieges. Earthworks were constructed in a ring around the City from Tothill Fields to the Tower in the north and from Vauxhall to Tooley Street in the south.[45]

This period saw the first major development of what is now known as London's West End. Aristocrats and land developers bought chunks of farmland and countryside around Westminster and built houses on it, hoping to turn a profit renting or leasing those houses. Unlike previous London townhouses, these new building efforts were generally in brick or stone rather than wood.[42] In particular, the Earl of Bedford, Francis Russell, commissioned Inigo Jones to turn fields and orchards west of the City into Covent Garden, a square of aristocratic townhouses surrounding a marketplace.[46] Jones based the project on the piazza in Livorno in Italy and the Place des Vosges in Paris, making the houses identical in order to give the impression that they were a single large mansion.[40] This was to become the model for future efforts: In 1690, the Reverend R. Kirk wrote, "Since the burning, all London is built uniformly, the streets broader, the houses all of one form and height".[47] Pall Mall and The Mall are built in 1661.[48] St. James' Square is built in 1665 under Henry Jermyn, Earl of St. Albans.[49] Three large mansions were built along Piccadilly- Burlington House, Clarendon House, and Berkeley House.[49] Leicester Square, Soho Square and Golden Square are built in the 1670s,[49] and Downing Street was built in 1682.[50] Queen Anne's Gate was built c.1704.[51] From the 1670s, sash windows were increasingly used on upmarket houses such as Montagu House and palaces like Hampton Court.[52]

Further west, in 1677, Thomas Grosvenor married Mary Davies, and thus gained her inheritance of 500 acres of marshland to the west of London. The family would go on to turn this land into the districts of Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico, much of which is still owned by the family today.[53] The builder Thomas Young laid out Kensington Square in 1685, and the royal court moved to the new Kensington Palace a few years later, increasing demand for houses in the area.[54]

The area known as Bloomsbury began to be built on in this period; Southampton Square was built in 1660.[55] Red Lion Square was built in the 1680s under the speculator Nicholas If-Jesus-Christ-had-not-died-for-thee-thou-hadst-been-damned Barbon.[49] Barbon also had George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street, Of Alley, and Buckingham Street built around the area of the Strand between 1674 and 1676.[42] Lord Hatton had a row of townhouses built called Hatton Garden, and Lincoln's Inn Fields and Great Queen Street were built under the landowner William Newton.[55]

The East End was similarly developed, although with working-class houses rather than aristocratic ones. Hoxton Square and the nearby Charles Square were both built in the 1680s.[56] The fields around St. Mary Spital church were filled in with houses, becoming Spitalfields, particularly after the influx of French Huguenot migrants in the 1680s and the establishment of a market in Spital Square in 1682.[56]

A great deal of rebuilding took place in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London in 1666. St. Paul's Cathedral was rebuilt under the architect Christopher Wren between 1670 and 1711.[1] He also rebuilt another 51 City churches, plus three outside the bounds of the Fire (St. Anne Soho, St. Clement Danes, and St. James Piccadilly), for which he worked unpaid, although he did receive generous bribes from the parish authorities.[57] King Street and Queen Street were both created in the aftermath of the Fire, and many churches, livery halls and the Royal Exchange were rebuilt.[58] After the Fire, laws were passed ensuring that new houses are built in stone or brick rather than wood.[58] The Monument to the Fire was completed in 1676.[49]

In 1661, the King Charles Block of Greenwich Palace was built, designed by John Webb.[43] The old, disused Greenwich Palace was converted into the Royal Hospital for Seamen in 1694, designed by Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor. This was not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but a place where retired or disabled sailors could have somewhere affordable to live.[59] A similar project was the Royal Hospital Chelsea, begun in 1682, but for soldiers rather than sailors.[43]

Other major new works in this period include Ham House (1610),[60] Charlton House (1612),[61] Forty Hall (begun 1629),[62] Eltham Lodge (1663), Lindsey House (1675), Gray's Inn (1676-1685),[63] Valentines Mansion (1690),[64] Fenton House (1693),[65] Schomberg House (1698),[14] Burgh House (1703),[39] and Marlborough House (1709).[66]

Transport

[edit]

In the 1660s, there were about 9,000 horse-drawn coaches on the streets of London, both privately-owned and hired.[67] Londoners could hail one of 400 hackney cabs that operated on the streets.[68] To get to and from London from the rest of the country, there were about 300 stage wagons, taking up to 20 people at a time.[69] There were stagecoaches operating to towns such as Dover, Exeter, Bristol, Chester, York, and Edinburgh.[70] These would take passengers to and from coaching inns, the one remaining survival of which in London is the George Inn, built from 1676.[71] In 1711, London saw its first turnpike road, with toll booths placed on part of the modern-day Edgware Road in order to pay for the road's upkeep.[72]

Londoners often used boats to get across, or up and downriver,[69] particularly as there was only one bridge across the river in the city at this time.[73] Both the king and the Lord Mayor had golden state barges to carry them about the Thames.[73] The most common boat on the Thames was a wherry- a river taxi that can seat up to five people.[73] There was a ferry at Westminster called the Horseferry, which crossed the river back and forth at Westminster.[73] Construction began on turning the River Fleet into a canal lined with wharves in 1670.[74]

War

[edit]

By 1640, Charles I had not called a Parliament in 11 years, and was badly in need of funds. In this year, he asked the City of London for a loan of £100,000, and when that was refused, the demand increased to £200,000 and then £300,000.[75] Four aldermen were imprisoned as punishment for refusing to pay.[75] From 1642, tensions between King Charles I and his Parliament broke out into the English Civil War. London's pro-Royalist Lord Mayor, Richard Gurney, was impeached by its pro-Parliament Common Council, but refused to give up his insignia of office.[76] In that year, Royalist forces marched on London from the west. They seized Syon House and bombarded Parliamentary barges on the Thames.[77] In November 1642, the Royalist Prince Rupert looted Brentford, but they were prevented from getting any closer to the capital.[77] In 1643, the City of London organised a ring of defences, often built by ordinary Londoners, including women and children.[78] Parliament captured the king, and in 1647 he was imprisoned in Hampton Court Palace for several months.[77] The Parliamentary New Model Army used Putney as their headquarters from November 1647, and held a series of meetings there to discuss the future of the country called the Putney Debates.[77]

In 1648, Henry Rich attempted to create an uprising in favour of the king, resulting in the Battle of Surbiton. However, he was summarily defeated and Londoners generally did not join the rebellion,[31] and Charles was executed on 30 January, 1649, outside Banqueting House.[31] Without a king, England entered an Interregnum period in which the country was controlled by Parliament, particularly its military leader, Oliver Cromwell, until his death in 1659. The Lord Mayor of London refused to proclaim the abolition of the monarchy, and was imprisoned in the Tower as a result.[31]

Woolwich was established as a military base in 1671, storing ordnance and experimental armaments.[59]

In 1685, the Catholic James II came to the throne, which angered anti-Catholic Anglicans and Dissenters.[79] After a failed rebellion by the Duke of Monmouth, James stationed troops outside London.[79] Seven bishops refused to accept a new law of his allowing greater toleration for Catholics and Nonconformists, and were imprisoned in the Tower of London, but were found not guilty. Londoners celebrated their release in the streets.[79] In 1688, several politicians contacted the husband of James' sister, William of Orange, inviting him to seize the throne.[79] He brought an army across the English Channel, arriving in London in November in what was known as the Glorious Revolution.[79] Afterwards, Parliament passed a law banning Catholics from taking the throne, and supporters of James and his descendants, known as Jacobites, continued to fight for the next 70 years.[79]

Health and medicine

[edit]

In non-plague years, the biggest cause of death in London from the 1660s-1690s was tuberculosis, being named as the cause of 18% of all deaths on average.[80] The second-biggest was "convulsions", or fits; the third was "ague and fever", which includes malaria; followed by "griping in the guts" (dysentery), smallpox and measles, rotten or abscessed teeth, old age, and dropsy.[80]

The preparations for the coronation of King James I and Anne of Denmark in 1603 were interrupted by a severe plague epidemic (which may have killed over 30,000 people) and by threats of assassination.[81] The Royal Entry to London was deferred until 15 March 1604.[82] Major epidemics of plague occurred in 1603, 1625, and most notably, 1665, known as the Great Plague.[83] Modern estimates place the number of deaths in the Great Plague at upwards of 100,000, over one-quarter of London's total population.[84][85]

London's two main hospitals were St. Bartholomew's and St. Thomas'.[86] There were a number of leper hospitals, including at Highgate (closed in 1653), and Kingsland in Hackney.[87] London had several hospitals for the mentally ill. The most famous was also the most notorious- St. Mary of Bethlehem, better known as Bedlam.[88] Inmates at Bedlam were able to be viewed by the public in return for a donation.[88] During this period, the hospital moved from its first location on Bishopsgate to a site in Moorfields.[88] In 1684, the hospital gained a new governor in Edward Tyson, who attempted to reform the institution somewhat by replacing the male warders with female nurses, and establishing a fund to provide clothing for the inmates.[89]

During this period, the Chamberlen family of midwives pioneered the use of forceps during a difficult birth.[90] Before the use of forceps, a child who could not be born was pulled out of the mother with hooks or cut up into smaller pieces, whereas the Chamberlens' method offered a chance of saving the baby as well as the mother.[90] To preserve their trade secret, they transported the forceps in an overly large wooden case.[90] The secret was so well-kept that no one else discovered it until after the last member of the family died without an heir in 1728.[90]

The most prestigious medical practitioners were the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, who could be hired to see private clients for large fees, and most of whom were based in London. The most celebrated single physician of the age may be Thomas Sydenham, known as "the English Hippocrates" due to his relatively high success rate.[91]

In 1674, the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries first opened their Physic Garden in Chelsea in order to grow plants for medicine.[53] The garden may have included England's first greenhouse, which was recorded there by John Evelyn in 1685.[92]

Education

[edit]

In 1611, the former monastery buildings at London Charterhouse were bought by Thomas Sutton, who died shortly afterwards. In Sutton's will, he left the bulk of his estate, including the buildings at Charterhouse, to establish Charterhouse School for 40 boys and almshouses for 80 pensioners.[93] These were opened in 1614.[94] In 1603, James I knighted 133 men in a single evening in its Great Hall, and its governors included famous figures of the day such as Francis Bacon, William Laud, and the Duke of Monmouth.[95]

The boys at St. Paul's School were known for their plays, which were attended by talent scouts from professional theatres such as the Globe.[96] Famous pupils of the school from this era include John Milton, Samuel Pepys, John Churchill,[96] and Edmond Halley.[97]

The Shakesperean actor Edward Alleyn founded Dulwich College as a school for poor boys in the 1610s.[98] The Latymer School in Fulham received its first students in 1627.[62] Colfe's School was refounded in 1652,[99] and Haberdashers' Aske's School was established in 1690.[64]

In 1698, a new group called the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge was founded at St. Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside.[100] The society in turn founded several charity schools, at which the students received a free uniform in a distinctive colour, often gaining a nickname such as "Bluecoats" or "Greencoats".[100] The Grey Coat Hospital School was one of these, founded by eight Westminster shopkeepers in order to educate the beggar children of the area.[100] In the next 12 years, 80 such schools were founded across London.[100]

Crime and law enforcement

[edit]

In October 1605, a search carried out in the basement of the Houses of Parliament revealed a man called Guy Fawkes with matches in his pocket and 36 barrels of gunpowder.[101] Fawkes had been recruited to join the Gunpowder Plot by a group of fellow Catholics including Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and John Wright.[102] The king was due to visit Parliament and Fawkes' plan was to blow the place up with the king inside. Several of the conspirators, including Fawkes, were hanged, drawn and quartered in Old Palace Yard in Westminster.[103]

A riot of London apprentices took place on Shrove Tuesday in 1617. The Cockpit Theatre on Drury Lane was stormed, and the mob destroyed the actors' costumes, sets and scripts. In Wapping, several houses were pulled down and the sheriff pelted with stones.[98] In 1661, a Christian sect called the Fifth Monarchists rioted in the streets for two days in London. They were led by a wine merchant called James Venner, and believed that they must pave the way for the return of Christ and the Fifth Monarchy prophesied by Daniel in the Bible. They opposed the Restoration of Charles II and the Church of England. About 40 people were killed during the riots.[104] On St. David's Day in 1662, the Welshmen of London celebrated by wearing a leek in their hats, while the English put up mocking dolls and scarecrows with leeks in their hats. While drunk, an English cook put a leek in his own hat and addressed a Welsh lord as his "fellow countryman". The mockery turned into a fight with swords drawn, and the Welsh lord and his retinue were forced to flee onto the Thames.[105] The Sacheverell Riots took place in 1710 in support of Henry Sacheverell, whose anti-Nonconformist sermons were thought seditious by the government. Nonconformist buildings and the homes of politicians were attacked. Sacheverell was found guilty, but given a very light sentence, and his supporters celebrated the verdict all over London.[106]

In 1674, workmen at the Tower of London discovered a box underneath a staircase containing the skeletons of two children. These were presumed to be the Princes in the Tower, 15th-century royal boys who were thought to have been murdered on the orders of Richard III. The bodies were buried in Westminster Abbey with royal honours.[53]

Duelling, either with pistols or with swords, was a popular way for upper-class men to settle arguments, although they were not legal. In 1694, a duel took place between John Law and Beau Wilson in Bloomsbury Square. Wilson was killed and Law convicted of his murder and sent to Newgate Prison.[65]

Each of the City's wards had a constable whose job was to keep order by breaking up fights and, if necessary, making arrests. There was a town watch made up of selected men who patrol the streets armed with halberds.[107] From the Interregnum period, London also had a trained band of soldiers who drilled in Finsbury Fields who marched about the city with pikes once a week. There were 800 Parliamentary soldiers who were stationed in the Old St Paul's Cathedral as it was a central meeting place at the time.[16]

Religious suppression

[edit]

Religion was very important in Stuart London, with one's chosen sect of Christianity often being a matter of life or death. Anti-Catholic feeling in particular was very strong. In 1662, the Act of Uniformity ordered everyone to worship according to the Church of England's 1662 Book of Common Prayer, and Charles II's attempts to introduce complete religious toleration in 1672 were thwarted due to anti-Catholic feeling, although non-demoninational Protestants were allowed to worship in licensed buildings, and Catholics were allowed to worship in private.[108] When the Catholic James II became king in 1688, London Catholics were able to openly celebrate Mass, with the diarist John Evelyn "not believing I should ever have lived to see such things in the King of England's palace, after it had pleased God to enlighten this nation".[79]

1678 saw the anti-Catholic mania of the Popish Plot. A man called Titus Oates went before the magistrate Edmund Godfrey to report a conspiracy of Catholics plotting to overthrow King Charles II in favour of his brother, the Catholic James II. Parliament empowered Oates with a band of armed men and permission to root out the conspirators. Godfrey was found murdered and an anti-Catholic panic quickly set in amongst Londoners. People were arrested simply for being in contact with Catholics, and Oates named five noblemen, one of whom, Lord Stafford, was executed. By 1681, 35 people had been executed as a result of Oates' fabrications.[109]

Nonconformist Protestants were similarly heavily persecuted, particularly after the Restoration of 1660, as nonconformists were thought to be particularly anti-monarchy. Under the 1665 Five Mile Act, nonconformist preachers and schools were banned from operating within five miles of the city walls, so chapels were often set up in London's outlying villages, in places like Highgate, Hampstead, and Chelsea.[110] England's first Baptist church was built in Spitalfields in 1612.[61] The Quaker movement was founded based on the preacher George Fox's teachings in the 1640s, but was heavily suppressed both legally and socially. Meetings of five or more Quakers were made illegal from 1662, and so many were imprisoned in London based on this law. A Quaker meeting house was built in London in 1668, despite the fact that attending meetings there did not become legal until the Toleration Act 1688, 20 years later.[111] The whole congregation of a Seventh Day Baptist church in Bulstake Alley, Whitechapel, was arrested and sent to Newgate Prison, and their preacher, John James, was found guilty of treason, and hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn.[112]

Punishments

[edit]

Capital and corporal punishments were widely used. Tyburn, the main execution ground after 1660,[113] had a unique three-sided gallows to allow 24 people to be hanged simultaneously.[114] For example, the famous highwayman Claude Duval was hanged at Tyburn in 1670.[74] Beheading was used as a punishment for those convicted of treason, such as the explorer Walter Raleigh, who was beheaded at the Old Palace Yard in Westminster in 1618.[115] A particularly famous executioner of the period was Jack Ketch, who beheaded the Duke of Monmouth in 1685.[54] The heads of people sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered were displayed on spikes over London Bridge[116] or Temple Bar.[117] When Charles II returned to London in 1660, those that had signed his father's death warrant were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered at Charing Cross.[118] Burning at the stake was used as a punishment for women convicted of treason, such as Sarah Elston, who was burned at Kennington Common in 1678 for the murder of her husband.[7] Pirates, having committed their crimes outside the British mainland, were generally hanged at Wapping on the water's edge, at low tide. Their bodies were left on the gallows until the tide had risen over them three times. Some were then dipped in tar and displayed in cages called gibbets along the river's edge as a warning to other would-be pirates.[119] Captain William Kidd was executed in this manner in 1701.[120] Those who refused to plead in court were sentenced to suffer peine forte et dure- being crushed under heavy stones and starved to death.[121] This was carried out on two men called David Pearce and William Stoaks after they refused to swear at the Old Bailey in 1673.[121]

Transportation was increasingly used throughout this period, generally to Virginia or Maryland in America. The ships which volunteered to transport prisoners could make money from contracting out their labour upon their arrival.[122]

Whipping and the pillory were common punishments for lesser offences.[123] In 1690, a boy called Philip Clarke was sentenced to walk with his hands tied to the back of a cart from Newgate Prison to Aldgate, being whipped along the way. His crime was stealing a pair of gloves.[123] Women and children were often sentenced to be whipped at Bridewell, which was seen as less publicly humiliating than being whipped through the streets.[123] In 1698, a captain called Edward Rigby was sentenced to the pillory for buggery, after being caught in a sting operation at the George Tavern on Pall Mall set up by the Society for the Reformation of Manners. He was able to draw on his powerful connections and was allowed to stand next to the pillory rather than be locked in it, with a guard of constables to make sure the crowd didn't become violent.[124]

London had several places to imprison those convicted of crimes and those awaiting a hearing, including the Tower of London, Ludgate, Newgate, Ely Place (from 1642), Poultry Compter, Wood Street Compter, the Fleet, Bridewell, Clerkenwell Bridewell, the Gatehouse at Westminster, Tothill Fields Bridewell, the Clink, the Marshalsea, the Clink Compter, and the King's Bench.[125] When prisons were overcrowded, it was easy for "gaol fever" (a form of typhus) to spread between inmates,[126] with Newgate in particular having such poor sanitary conditions that shops in the local area closed in warm weather because of the smell.[127] The Fleet Prison was known for its priests who could perform speedy or secret marriages.[128] Debtors' prisons such as the Fleet existed to incarcerate people who could not pay off their debts. Until 1670, debtors had to pay for bed and board inside the gaol; after this date, any debtor who had less than £10 could have their creditors pay for their upkeep. In 1671, the publisher Moses Pitt wrote a condemnation of his time in the Fleet Prison called The Cry of the Oppressed.[129]

There are also examples of Londoners carrying out extra-legal punishments in this period. For example, in 1696, a tailor breached the sanctuary of the Savoy in order to collect a debt he was owed. He was tarred and feathered and tied to the local maypole.[130]

Trade and industry

[edit]

This period saw the establishment of many large and important banking institutions in London. Francis Child established Child's Bank; Richard Hoare established C. Hoare & Co.; John Freame and Thomas Gould established what would become Barclays Bank, and John Campbell founded Coutts Bank in 1692.[131] The Bank of England was founded in 1694, and it soon began issuing its first banknotes.[132] In 1659, the first cheque was paid out, by the bankers Clayton & Morris on Cornhill.[133] In the 1690s, England's coinage was in crisis due to large amounts of coin clipping. The scientist Isaac Newton was put in charge of the Royal Mint in the Tower of London, and under his leadership it produced an entirely new coinage.[134]

Edward Lloyd's Coffee House opened in the 1680s and was particularly popular with ship captains and insurance underwriters. By 1692, Lloyd was producing a newsletter which went on to become Lloyd's List, and the coffee house still lends its name to Lloyd's of London, one of the largest insurance markets in the world.[135] In 1698, John Castaing began to list stock prices for joint-stock companies in a newsletter called The Course of the Exchange (referring to the Royal Exchange), presaging the development of the stock market.[135]

Certain streets were often known for a particular kind of shop or trade. For example, Thames Street was known for candlemakers, Cheapside for goldsmiths, Cannon Street for linen shops, and Little Britain for second-hand book stalls.[136] There were four large Exchanges which acted as luxury shopping centres as well as meeting places for merchants; the Royal Exchange on Cornhill, and the New Exchange, the Middle Exchange, and the Exeter Exchange on the Strand.[137] The two main general markets were on Cheapside and Gracechurch Street.[138] There was a fruit and vegetable market on Aldersgate Street, a fish market on Billingsgate, a cloth market at Blackwell Hall, a meat market on Eastcheap, a fish market on Fish Street Hill, a meat and leather market at Leadenhall, a meal market on Newgate Street, a fish market on Old Fish Street, a meal and flour market at Queenhithe, a meat market at St. Nicholas Shambles, a fruit and vegetable market in St. Paul's Churchyard, a livestock market at Smithfield, and a meat and fish market at Stocks.[138] From 1670, Covent Garden became an important fruit, vegetable and flower market for the newly-built West End.[139]

London became a major hub at the centre of a burgeoning empire. The East India Company was established just before the beginning of the period, in 1600, and continued to operate from various London headquarters throughout, establishing trading posts in India.[56] In 1607, they opened a shipbuilding yard at Blackwall.[140] In 1606, a voyage from Blackwall set off to colonise Virginia in America.[141] Goods flowed into London's port from colonies in North America, including colonies in the West Indies which relied on slave labour.[56] As the amount of shipping coming into London grew, the wharves in the Pool of London- the part of the Thames next to the City- grew increasingly crowded, and so docks further downstream in places like Deptford, Greenwich and Poplar became more important.[140]

Culture and entertainment

[edit]

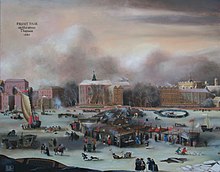

Several large fairs were held throughout the year around London, with the largest being Bartholomew Fair in Smithfield, held at the end of August.[142] It featured acrobats, circus acts, freak shows and theatrical performances alongside market stalls. Famous performers in London included the acrobat Jacob Hall.[143] St. Margaret's Fair took place in Southwark in September,[144] and a May Fair was held in the region of modern-day Mayfair. Its most famous character was a gingerbread seller called Tiddy Doll, who dressed like a gentleman with a suit trimmed in gold lace.[66] In January 1684, a frost fair was held on the Thames, which had frozen solid enough not only to walk on, but to drive a coach, erect tents, and even roast an ox on.[145] Many of the traditional celebrations for religious festivals such as Christmas were banned or suppressed during the Interregnum period.[99]

Blood sports such as bear-baiting, bull-baiting and cockfights were popular, and there is even a recorded instance of lion-baiting in 1604, when three mastiffs were pitted against a lion from the Tower of London with the king and queen in attendance. The lion and one of the dogs survived; the dog was adopted by St. James's Palace as a reward.[146]

In Lambeth, visitors could see Tradescant's Ark, a collection of rare plants and other curios put together by John Tradescant the Elder and John Tradescant the Younger.[147] Other private houses had similar collections of curiosities, such as that belonging to Thomas Browne, William Charlton, the Royal Society, and Hans Sloane, the latter of which went on to become the core of the British Museum.[147]

Tourists came to London for sightseeing, particularly Whitehall Palace, the Royal Exchange, Westminster Abbey, Nonsuch Palace, St. Paul's Cathedral, Hampton Court Palace, the tapestry makers at Mortlake, and the Tower of London.[148]

1661 saw the opening of Vauxhall Gardens, which featured ornamental plantings, concerts, food and spectacles, and was known as a place to have secret liaisons.[48]

Literature

[edit]

Poetry was the most important form of literature in this period.[149] Famous poets of the period included William Shakespeare, John Denham, Margaret Cavendish, John Milton, and John Dryden.[149] In 1668, Charles II appointed John Dryden as the very first Poet Laureate. He was succeeded by Thomas Shadwell and Nahum Tate.[149]

The form of the novel began to coalesce in the latter half of the period, with works by London authors such as John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and Aphra Behn's Oroonoko.[150] There were also important works of philosophy being written such as Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan and John Locke's Two Treatises of Government.[151]

London saw several wealthy men accrue large private libraries in this period. Lambeth Palace Library was founded in 1610 by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Richard Bancroft.[60] The largest private library in the country was owned by the Earl of Anglesey, Arthur Annesley, at his house near Drury Lane. It was broken up after his death in 1686.[152] The Bishop of Worcester's house in Twickenham had 6,000 books in 1689, and the diarist John Evelyn had 5,000.[152] St. James' Palace had the "Old Royal Library", containing 2,000 medieval manuscripts.[152]

Other important publications from this period include Britain's first daily newspaper, The Daily Courant, which began publication in London in 1702, and could be bought near the Fleet Bridge;[120] and The Tatler, which was first published in 1709, and contained society gossip and caricatures of prominent figures.[66]

Theatre

[edit]

The playwright William Shakespeare was working in London at the beginning of this period, and some of his most famous tragedies come from the 1600s, such as Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth.[153] Within ten days of taking the throne, King James I gave Shakespeare's theatre troupe his royal patronage, making them the "King's Men".[154] In 1608, the company moved into a site at Blackfriars and built their first indoor theatre.[155] It had 700 seats, was lit by candlelight, and had a roof, meaning the company could put on plays during winter.[155] In 1623, after Shakespeare's death, his colleagues John Heminges and Henry Condell published a collected version of his plays known as the First Folio.[156]

James I was particularly fond of a type of theatre called a masque.[157] These featured courtiers, or occasionally even the king himself, dressed as allegorical concepts and included song, dance, and live animals.[157] They were the only mode of theatre at the beginning of the period open to women.[157] The playwright Ben Jonson also wrote masques, such as Satyr and The Masque of Blackness.[158] The opening of the New Exchange on 11 April 1609,[159] a market and retail centre, was celebrated with a masque, The Entertainment at Britain's Burse,[160] and the Lord Mayor's Show, which had been discontinued for some years, was revived by order of the king. In 1610, Prince Henry was made Prince of Wales. The event was celebrated by another masque, Tethys' Festival at Whitehall Palace and a pageant on the River Thames, London's Love to Prince Henry.[161]

During the Interregnum period, masques[162] and maypoles were prohibited.[16] All London playhouses, including the Globe Theatre, were closed in 1642, and either converted to other uses or destroyed.[163] The theatrical producer William Davenant was able to circumvent the law on theatre by adding music to his play and advertising it as a concert. It became The Siege of Rhodes, the first true English opera, and premiered in London in 1656.[164] It was also the first English production to use scenery.[164] After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant were given an exclusive royal licence to stage plays in London.[165] They formed the King's Company and the Duke's Company, the two main acting troupes in the capital.[165] The King's Company initially had their home at Gibbon's Tennis Court in Vere Street, and in 1663 opened their Theatre Royal in Bridges Street, which burned down in 1672.[165] The Duke's Company was first based in the Salisbury Court Theatre, then in the Duke's Theatre in Lincoln's Inn Fields, and from 1671 in the Dorset Garden Theatre.[165] In 1682 the two companies merged to form the United Company,[165] putting on operas at the Dorset Garden Theatre and straight plays at the Theatre Royal.[165] In 1695, a group of actors from the United Company split off to form their own company at the Duke's Theatre.[165]

Successful playwrights of the Restoration period included John Dryden, George Etherege, Charles Sedley, William Wycherley, Thomas Shadwell, Thomas Otway, John Vanbrugh, William Congreve, and Aphra Behn (often called the first British woman to make a living from writing).[166] The most famous actor of the Restoration period was Thomas Betterton.[167] Women actresses began to appear onstage in London from 1661, and the most famous are Nell Gwyn, Elizabeth Barry and Anne Bracegirdle.[168]

The Italian theatrical form of commedia dell'arte came to London, featuring half-masked actors or puppets playing recurring characters such as Harlequin, Columbine, and Pierrot.[169] The traditional Punch and Judy puppet show grew out of the commedia dell'arte tradition, and was first recorded in London in 1662.[169]

Sports

[edit]Bowling was incredibly popular, with bowling greens and alleys set up in the Fleet Prison, and even on a boat floating on the Thames.[170] The diarist Samuel Pepys played with his wife in 1661.[170] Its popularity came from it being one of the few sports that men and women could play together, and many people gambled large sums on the outcome of games.[170]

Pepys also attended a fencing display at the New Theatre near Lincoln's Inn Fields. These were popular forms of entertainment, and the fencers used swords that were only slightly blunted, so both participants were liable to be covered in blood by the end.[171] Wrestling matches took places in Moorfields or in the Bear Garden on Bankside, and saw some of the largest amounts of gambling outside of horse races. In 1667, a team of West Countrymen won a wrestling competition against a team of northerners in St. James's Park for a cash prize of £1000.[148]

Music

[edit]Most forms of music were forbidden during the Interregnum period, but after Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, church music, cathedral choirs, church organs, and tavern music were reinstated.[162] Nicholas Lanier was the Master of the King's Music for Charles I and Charles II, and was succeeded by Louis Grabu.[172] The public concert was developed in this period, with the first example often cited as John Banister's 1672 violin recital near Temple Church in London.[173] Significant London composers include Matthew Locke, Henry Lawes, Pelham Humfrey, William Turner, John Blow, and most famously, Henry Purcell.[173]

Art

[edit]Grinling Gibbons was a master woodcarver working in London in this period, living in a small thatched cottage in Deptford.[174]

The art-form of portraiture was particularly strong in this period, fuelled by major court painters such as Anthony van Dyck, Peter Lely, and Godfrey Kneller.[175] The court painter John Riley painted full-length portraits of servants at the court of King William and Queen Mary, including one of Bridget Holmes, the woman who emptied the king's chamber pot.[176] London saw its first professional female artists in this period, such as Mary Beale.[177]

Peter Paul Rubens was active in London during this period, painting the ceiling of Banqueting House in the Palace of Whitehall.

Food and drink

[edit]

One important feature of London culture were the coffeehouses which opened up from the 1650s onwards. London's first coffeehouse opened in 1652, and by 1663, there were 82 in London.[178] The first coffeehouses were harassed by city authorities as public nuisances,[15] but the 1660s saw their business explode with the restoration of the monarchy and the development of a lively political culture.[179] Coffee and tea were novelty refreshments in England, but the purpose of the coffeehouse expanded well beyond serving exotic drinks to serve as multi-functional venues for socializing, debate, to trade gossip, and conduct business. Coffee houses also functioned as shops where customers could post and receive mail, and buy the latest books, gazettes, and stationery.[180] In London, certain coffeehouses were defined by the professionals who met there to conduct business; some businessmen even maintained regular "office hours" at their coffeehouses of choice. Both Batson's on Cornhill and Garraway's in Change Alley were known for their doctors, surgeons, and apothecaries; the former served as an informal consulting room for doctors and their patients.[181] The Grecian was attended by lawyers, the Jerusalem was a meeting place for West Indian traders, and the Baltic on Threadneedle Street was a meeting place for Russian traders.[182] One such business, Lloyd's Coffee House (established 1686), became an exchange for merchants and shipowners who met there daily to insure ships and cargoes, and to trade intelligence on world trade, shipping disasters, and maritime news.[183] This coffee house would go on to lend its name to the insurance market Lloyd's of London.[180][184] Other coffeehouses were distinctly political in character: the St. James's on St. James's Street and Old Slaughter's were frequented by Whigs, while the Tories and Jacobites preferred the Coffee-Tree on the corner of St. James's Street and Pall Mall.[182][185] In 1706, Tom's Coffee House off the Strand was bought by Thomas Twining, who began selling tea there as well as coffee, and later founded the Twinings tea company.[186]

Besides coffeehouses, the main public eating and meeting areas were alehouses and victualling-houses, of which London had around 1,000 during the Stuart era.[16] The word "restaurant" did not yet exist, but London had many eateries in the form of inns, cookshops, ordinaries, taverns and eating houses.[67] The largest inn in London was the Angel, with 20 rooms.[187] The most exclusive establishments were based on French cooking, like Chatelin's in Covent Garden, and Pontac's Head in Abchurch Lane.[67] The long-standing gentlemen's club White's was founded in 1693 as White's Chocolate House on St. James's Street.[65]

Britain's strengthening connections to the wider world meant that Londoners were able to access and afford foreign foods like coffee, tea, chocolate, and sugar cane more easily.[188]

The Black Eagle Brewery on Brick Lane was founded in 1661.[74]

Science

[edit]

In 1609, William Harvey was appointed physician at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, and in 1618, he became a physician to the king himself.[189] In 1628, Harvey published De Motu Cordis, a landmark step in the knowledge of how blood circulation works.[189] The physician Edward Tyson performed animal dissections to show the relationships between various species, founding the study of comparative anatomy.[89] In 1680, he bought the body of a porpoise which had swum up the Thames, and publicly dissected it at Gresham College, discovering that it was not a fish, but a mammal.[89] He published a book called Anatomy of a Porpess detailing his findings later that year.[89] In 1698, he dissected a chimpanzee (which he misidentified as an orangutan) which had been brought from Africa, and showed the similarities between apes and humans.[89]

The Royal Society was formed in 1662 in London, as a club for gentlemen to share scientific knowledge and new understanding.[190] They hired Robert Hooke to perform new experiments each week, making him the world's first paid professional research scientist.[191] In 1665, Hooke published Micrographia, showing detailed illustrations of things that could only be seen through a microscope.[192] In 1687, the Society published Isaac Newton's seminal Philosophae Naturalis Principia Mathematica,[193] and Newton was made President of the Society in 1695.[194]

New inventions and experiments were trialled out or displayed in London, particularly towards the end of the period. London was one of the few places where scientific instruments like thermometers, barometers, telescopes and accurate clocks could be bought.[192] The famous clockmaker Thomas Tompion had a shop at the junction of Fleet Street and Water Lane.[136] In 1660, a set of water-lifting machines were put on public display in St. James's Park.[195] In 1698, Thomas Savery demonstrated a steam engine for pumping water out of mines before the Royal Society.[195]

In 1675, Charles II established the Royal Observatory in Greenwich,[59] with John Flamsteed as its first Astronomer Royal.[196] Later that year, Flamsteed was visited by the astronomer Edmond Halley. In 1678, Halley published a catalogue of stars of the southern hemisphere that he had compiled during a voyage to St. Helena, and became a Fellow of the Royal Society.[89]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Bastable, Jonathan (2011). Inside Pepys' London. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4463-5526-8.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Werner, Alex (1998). London Bodies. London: Museum of London. p. 108. ISBN 090481890X.

- ^ Tinniswood, Adrian (2003). By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire of London. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-224-06226-8.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 155.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 156.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 166.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Custalow, Dr. Linwood "Little Bear"; Daniel "Silver Star", Angela L. (2007). The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 9781555916329.

- ^ Fruin-Mees, Willemine (1900). A mission of two ambassadors from Bantam to London, 1682. Jakarta: Jajasan Purbakala; Archaeological Foundation. OCLC 1355189481.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2000, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Pearse, Malpas (1969). Stuart London. London: Macdonald. pp. 9, 13, 28, 44. ISBN 978-0-356-02566-7.

- ^ "Velho Cemetery of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish Congregation of London, Non Civil Parish - 1319658". Historic England. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 82.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 110.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 119.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 121.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 120-121.

- ^ Mortimer, Ian (2017). The Time Traveller's Guide To Restoration Britain. London: The Bodley Head. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781847923042.

- ^ Tinniswood 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 10.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 214.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 10-12.

- ^ "Fire in the City". City of London. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 132.

- ^ a b Tinniswood 2003, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2000, p. 133.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 134.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2001). London: The Biography. Random House. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-09-942258-7.

- ^ Schama 2001, p. 269.

- ^ Bruce Robinson (29 March 2011). "London's Burning: The Great Fire". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Hutton 1993, p. 249.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 28-29.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 149.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d Pevsner, Nikolaus (1973). London: The Cities Of London And Westminster (3rd ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 57. ISBN 0140710124.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Pevsner 1973, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Pevsner 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 83.

- ^ Barratt, Nick (2012). Greater London: The Story of the Suburbs. London: Random House Books. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84794-532-7.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 14.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 64.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e Mortimer 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 79.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 251.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 151.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 161.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Barratt 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 66.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Barratt 2012, p. 78.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 114.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 115.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Pevsner 1974, p. 22.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 164.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 273.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 216.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 215.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 218.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). London: Except the Cities of London and Westminster. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-14-071006-9.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Mortimer 2017, p. 224.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 148.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 128.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Barratt 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morgan, Kenneth O., ed. (2005). The History of Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-911251-7.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 300.

- ^ Ian W. Archer, 'City and Court Connected: The Material Dimensions of Royal Ceremonial, ca. 1480–1625', Huntington Library Quarterly, 71:1 (March 2008), p. 160.

- ^ Mark Hutchings & Berta Cano Echevarría, 'The Spanish Ambassador's Account of James I’s Entry into London, 1604', The Seventeenth Century 33:3 (2018) pp. 255–277.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 301.

- ^ Walter George Bell (1951). The Great Plague of London. p. 13.

- ^ John S. Morrill. "Great Plague of London". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 318.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 309.

- ^ a b c d e f Gribbin 2002, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d Mortimer 2017, p. 310.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 315.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 160.

- ^ Oswald, Arthur (1959). The London Charterhouse Restored. Country Life Ltd. p. 6. OCLC 24426320.

- ^ Oswald 1959, p. 8.

- ^ Oswald 1959, p. 24.

- ^ a b Pearse 1969, p. 30.

- ^ Gribbin 2002, p. 164.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 118.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2000, p. 168.

- ^ Wharam 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Wharam 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Wharam 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 105.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 117-118.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 174.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 327.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 102-103.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 107.

- ^ Pearse 1969, p. 99.

- ^ Byrne 1992, p. 192.

- ^ Wharam, Alan (2005). Treason: Famous English Treason Trials. Stroud: Sutton. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-7509-3918-8.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 335.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 150.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 138.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 336.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 169.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 339.

- ^ Byrne 1992, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 341.

- ^ Cook, Matt (2007). A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex Between Men Since The Middle Ages. Oxford: Greenwood World Publishing. ISBN 9781846450020.

- ^ Byrne, Richard (1992). Prisons and Punishments of London. Grafton. ISBN 978-0-586-21036-9.

- ^ Byrne 1992, p. 27.

- ^ Byrne 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Byrne 1992, p. 66.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 340.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 165.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 171-172.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 173.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 137.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 171.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 172.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 180.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 181.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 182.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 183.

- ^ a b Barratt 2012, p. 76.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 346.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 347.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 348.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 350.

- ^ Richardson, John (2000). The Annals of London: A Year-By-Year Record of a Thousand Years of History. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-520-22795-8.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 367.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 365.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 381.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 377.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 379.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 375.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (1999). William Shakespeare: His Life and Work (2000 ed.). London: Abacus. p. 331. ISBN 0349112401.

- ^ Holden 1999, p. 206.

- ^ a b Holden 1999, p. 258.

- ^ Holden 1999, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Holden 1999, p. 270.

- ^ Holden 1999, p. 271.

- ^ Francis Sandford, A genealogical history of the kings of England, and monarchs of Great Britain (London, 1677), p. 525

- ^ Martin Butler, The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture (Cambridge, 2008), p. 80.

- ^ Martin Wiggins & Catherine Richardson, British Drama 1533-1642: A Catalogue: 1609-1616, vol. 3 (Oxford, 2015), pp. 72-4.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 387.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 390.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 391.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mortimer 2017, p. 391-392.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 394-397.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 398.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 399-400.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 349.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2017, p. 355.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 357.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 388.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 389.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 247.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 370-371.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 373.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 374.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 284.

- ^ Ellis, Aytoun (1956). The Penny Universities; A History of the Coffee-houses. London: Decker & Warburg. p. 223.

- ^ a b Matthew White (21 June 2018). "Newspapers, gossip, and coffeehouse culture". British Library. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Ackroyd 2001, p. 314.

- ^ a b Ackroyd 2001, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Lillywhite, 1963. p 330

- ^ "Edward Lloyd and His Coffeehouse". www.lr.org. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Schama 2001, p. 344.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 239.

- ^ Morgan 2005, p. 240.

- ^ a b Gribbin, John (2002). Science, a History: 1543-2001. London: Allen Lane. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7139-9503-9.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 134.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 135.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 136.

- ^ Mortimer 2017, p. 93.

- ^ Gribbin 2002, p. 189.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2017, p. 137.

- ^ Gribbin 2002, p. 165.