Swinging Sixties

| Part of the counterculture of the 1960s | |

| |

| Date | 1960s |

|---|---|

| Location | United Kingdom |

| Also known as | Swinging London |

| Outcome | Changing social, political and cultural values |

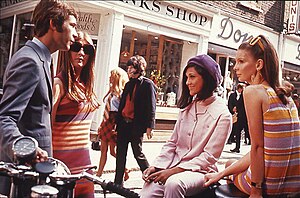

The Swinging Sixties was a youth-driven cultural revolution that took place in the United Kingdom during the mid-to-late 1960s, emphasising modernity and fun-loving hedonism, with Swinging London denoted as its centre.[1] It saw a flourishing in art, music and fashion, and was symbolised by the city's "pop and fashion exports", such as the Beatles, as the multimedia leaders of the British Invasion of musical acts; the mod and psychedelic subcultures; Mary Quant's miniskirt designs; popular fashion models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton; the iconic status of popular shopping areas such as London's King's Road, Kensington and Carnaby Street; the political activism of the anti-nuclear movement; and the sexual liberation movement.[1]

Music was an essential part of the revolution, with "the London sound" being regarded as including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Kinks and the Small Faces, bands that were additionally the mainstay of pirate radio stations like Radio Caroline, Wonderful Radio London and Swinging Radio England.[2] Swinging London also reached British cinema, which according to the British Film Institute "saw a surge in formal experimentation, freedom of expression, colour, and comedy", with films that explored countercultural and satirical themes.[1] During this period, "creative types of all kinds gravitated to the capital, from artists and writers to magazine publishers, photographers, advertisers, film-makers and product designers".[2]

During the 1960s, London underwent a "metamorphosis from a gloomy, grimy post-war capital into a bright, shining epicentre of style".[2] The phenomenon has been agreed to have been caused by the large number of young people in the city—due to the baby boom of the 1950s—and the postwar economic boom.[2] Following the abolition of the national service for men in 1960, these young people enjoyed greater freedom and fewer responsibilities than their parents' generation,[2] and "[fanned] changes to social and sexual politics".[1]

Shaping the popular consciousness of aspirational Britain in the 1960s, the period was a West End–centred phenomenon regarded as happening among young, middle class people, and was often considered as "simply a diversion" by them. The swinging scene also served as a consumerist counterpart to the more overtly political and radical British underground of the same period. English cultural geographer Simon Rycroft wrote that "whilst it is important to acknowledge the exclusivity and the dissenting voices, it does not lessen the importance of Swinging London as a powerful moment of image making with very real material effect."[3]

Background

[edit]The Swinging Sixties was a youth movement emphasising the new and modern. It was a period of optimism and hedonism, and a cultural revolution. One catalyst was the recovery of the British economy after post-Second World War austerity, which lasted through much of the 1950s.[4]

"The Swinging City" was defined by Time magazine on the cover of its issue of 15 April 1966.[5] In a Piri Halasz article 'Great Britain: You Can Walk Across It on the Grass',[6] the magazine pronounced London the global hub of youthful creativity, hedonism and excitement: "In a decade dominated by youth, London has burst into bloom. It swings; it is the scene",[7][8] and celebrated in the name of the pirate radio station, Swinging Radio England, that began shortly afterwards.

The term "swinging" in the sense of hip or fashionable had been used since the early 1960s, including by Norman Vaughan in his "swinging/dodgy" patter on Sunday Night at the London Palladium. In 1965, Diana Vreeland, editor of Vogue magazine, said that "London is the most swinging city in the world at the moment."[9] Later that year, the American singer Roger Miller had a hit record with "England Swings", although the lyrics mostly relate to traditional notions of Britain.

Music

[edit]

Already heralded by Colin MacInnes' 1959 novel Absolute Beginners which captured London's emerging youth culture,[10] Swinging London was underway by the mid-1960s and included music by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Who, Small Faces, the Animals, Dusty Springfield, Lulu, Cilla Black, Sandie Shaw and other artists from what was known in the US as the "British Invasion".[11] Psychedelic rock from artists such as Pink Floyd, Cream, Procol Harum, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Traffic grew significantly in popularity.

Large venues, besides former music halls, included Hyde, Alexandra and Finsbury Parks, Clapham Common and the Empire Pool (which became Wembley Arena). This sort of music was heard in the United Kingdom on TV shows such as the BBC's Top of the Pops (where the Rolling Stones were the first band to perform with "I Wanna Be Your Man"), and ITV's Ready Steady Go! (which would feature Manfred Mann's "5-4-3-2-1" as its theme tune), on commercial radio stations such as Radio Luxembourg, Radio Caroline and Radio London, and from 1967 on BBC Radio One.[12][13]

The Rolling Stones' 1966 album Aftermath has been cited by music scholars as a reflection of Swinging London. Ian MacDonald said, with the album the Stones were chronicling the phenomenon, while Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon called it "the soundtrack of Swinging London, a gift to hip young people".[14]

Fashion and symbols

[edit]During the Swinging Sixties, fashion and photography were featured in Queen magazine, which drew attention to fashion designer Mary Quant.[15][16] Mod-related fashions such as the miniskirt stimulated fashionable London shopping areas such as Carnaby Street and King's Road, Chelsea.[17][18] Vidal Sassoon created the bob cut hairstyle.[19]

The model Jean Shrimpton was another icon and one of the world's first supermodels.[20] She was the world's highest paid[21] and most photographed model[22] during this time. Shrimpton was called "The Face of the '60s",[23] in which she has been considered by many as "the symbol of Swinging London"[21] and the "embodiment of the 1960s".[24]

Like Pattie Boyd, the wife of Beatles guitarist George Harrison, Shrimpton gained international fame for her embodiment of the "British female 'look' – mini-skirt, long, straight hair and wide-eyed loveliness", characteristics that defined Western fashion following the arrival of the Beatles and other British Invasion acts in 1964.[25] Other popular models of the era included Veruschka, Peggy Moffitt and Penelope Tree. The model Twiggy has been called "the face of 1966" and "the Queen of Mod", a label she shared with, among others, Cathy McGowan, the host of the television rock show Ready Steady Go! from 1964 to 1966.[26]

The British flag, the Union Jack, became a symbol, assisted by events such as England's home victory in the 1966 World Cup. The Jaguar E-Type sports car was a British icon of the 1960s.[27]

In late 1965, photographer David Bailey sought to define Swinging London in a series of large photographic prints.[28] Compiled into a set titled Box of Pin-Ups, they were published on 21 November that year.[29] His subjects included actors Michael Caine and Terence Stamp; musicians John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger and five other pop stars; Brian Epstein, as one of four individuals representing music management; hairdresser Vidal Sassoon, ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev, Ad Lib club manager Brian Morris, and the Kray twins; as well as leading figures in interior decoration, pop art, photography, fashion modelling, photographic design and creative advertising.[28]

Bailey's photographs reflected the rise of working-class artists, entertainers and entrepreneurs that characterised London during this period. Writing in his 1967 book The Young Meteors, journalist Jonathan Aitken described Box of Pin-Ups as "a Debrett of the new aristocracy".[30]

Film

[edit]

The phenomenon was featured in many films of the time, including Darling (1965) starring Julie Christie, The Pleasure Girls (1965),[31] The Knack ...and How to Get It (1965), Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup (1966), Alfie (1966) starring Michael Caine, Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Georgy Girl (1966), Kaleidoscope (1966), The Sandwich Man (1966), The Jokers (1967), Casino Royale (1967) starring Peter Sellers, Smashing Time (1967), To Sir, with Love (1967), Bedazzled (1967) starring Dudley Moore and Peter Cook, Poor Cow (1967), I'll Never Forget What's'isname (1967), Up the Junction (1968), Joanna (1968), Otley (1968), The Strange Affair (1968), Baby Love (1968), The Magic Christian (1969), The Touchables (1968), Les Bicyclettes de Belsize (1969), Two Gentlemen Sharing (1969), Performance (1970), and Deep End (1970).[32]

The comedy films Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997) and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), written by and starring Mike Myers, resurrected the imagery of the Swinging London scene (but were filmed in Hollywood), as did the 2009 film The Boat That Rocked.[27]

Television

[edit]- The ITV spy-fi series The Avengers (1961–1969), particularly after it began broadcasting in colour, revelled in its Swinging Sixties setting.[33] In the 1967 episode "Dead Man's Treasure", Emma Peel (played by Diana Rigg) arrives in the archetypal English village of Swingingdale, dubbing it "not very swinging".

- In the episode "Beauty Is an Ugly Word" (1966) of BBC's Adam Adamant Lives!, Adamant (Gerald Harper), an Edwardian adventurer suspended in time since 1902, was told, "This is London, 1966 – the swinging city."[34]

- The BBC show Take Three Girls (1969) is noted for Liza Goddard's first starring role, an evocative folk-rock theme song ("Light Flight" by Pentangle), a West Kensington location, and scenes in which the heroines were shown dressing or undressing.[35]

- "Jigsaw Man", a 1968 episode of the detective series Man in a Suitcase, opened with the announcement: "This is London … Swinging London."[36]

See also

[edit]- 1960s in fashion

- Cool Britannia, a Britain-wide phenomenon in the 1990s and 2000s

- Freakbeat

- Timeline of London 1940s–1990s

- UK underground – London 1960s counter-culture, or underground, scene

- Yé-yé

- Youthquake (movement)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Wakefield, Thirza (15 July 2014). "10 great films set in the swinging 60s". British Film Institute. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Swinging 60s – Capital of Cool". History. AETN UK. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Rycroft, Simon (2016). "Mapping Swinging London". Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London 1950–1974. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-317-04734-6.

- ^ "Going Platinum: The UK's 70 years of change". HSBC. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

1950s and 1960s: the post-war investment boom. When the Queen came to the throne, the UK economy was still in its post-war boom period

- ^ "TIME Magazine Cover: London – Apr. 15, 1966". Time. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Rycroft, Simon (2012). Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London 1950–1974. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-8887-3. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "The Diamond Decades: The 1960s". The Daily Telegraph. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ most famous (if not the first) identification of Swinging London Gilbert, David (2006) "'The Youngest Legend in History': Cultures of Consumption and the Mythologies of Swinging London" The London Journal 31(1): pp. 1–14, page 3, doi:10.1179/174963206X113089

- ^ Quoted by John, Weekend Telegraph, 16 April 1965; and in Pearson, Lynn (2007) "Roughcast textures with cosmic overtones: a survey of British murals, 1945–80" Decorative Arts Society Journal 31: pp. 116–37

- ^ "Absolute MacInnes: British identity and society". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Ira A. Robbins. "British Invasion (music) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "BBC says fond farewell to Top of the Pops". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Roberts, David (1998). Guinness Rockopedia (1st ed.). London: Guinness Publishing Ltd. p. 258. ISBN 0-85112-072-5.

- ^ Norman 2001, p. 197; Moon 2004, p. 697; MacDonald 2002; Margotin & Guesdon 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Barry Miles (2009). The British Invasion: The Music, the Times, the Era. Sterling. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4027-6976-4.

- ^ Ros Horton, Sally Simmons (2007). Women Who Changed the World. Quercus. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-84724-026-2.

- ^ Armstrong, Lisa (17 February 2012). "Mary Quant: 'You have to work at staying slim—but it's worth it'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ DelaHaye, Amy (2010). Steele, Valerie (ed.). The Berg Companion to Fashion. Oxford: Berg. pp. 586–588. ISBN 978-1-84788-563-0.

- ^ "Telegraph obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Anya (10 May 2004). "Small is still beautiful". Daily Post.

- ^ a b "The Girl Behind The World's Most Beautiful Face". Family Weekly. 8 February 1967.

- ^ Cloud, Barbara (11 June 1967). "Most Photographed Model Reticent About Her Role". The Pittsburgh Press.

- ^ "Jean Shrimpton, the Famed Face of the '60s, Sits Before Her Svengali's Camera One More Time". 30 May 1977.

- ^ Patrick, Kate (21 May 2005). "New Model Army". Scotsman.com News.

- ^ Hibbert, Tom (1982). "Britain invades the world: Mid-Sixties British Music". The History of Rock. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Fowler, David (2008) Youth Culture in Modern Britain, C.1920–c.1970: From Ivory Tower to Global Movement – A New History p. 134. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008

- ^ a b John Storey (2010). "Culture and Power in Cultural Studies: The Politics of Signification". p. 60. Edinburgh University Press

- ^ a b Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002) [1983]. The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles. New York, NY: New American Library. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

- ^ Bray 2014, p. xii.

- ^ Bray 2014, pp. 252–53.

- ^ Mitchell, Neil (2011). World Film Locations: London. Intellect Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-84150-484-1.

- ^ "10 great films set in the swinging 60s". BFI.org. 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Patrick Macnee: five things you didn't know about Avengers star", The Week, 26 June 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook (2015). White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties. Hatchett UK

- ^ Falk, Quentin; Falk, Ben (2005). Television's Strangest Moments: Extraordinary But True Tales from the History of Television. Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-86105-874-4.

- ^ "Man in a Suitcase (1967–68)". CTVA. Retrieved 10 November 2016

Bibliography

[edit]- Beard, Chris (Joe) (2014). Taking the Purple: The Extraordinary Story of The Purple Gang – Granny Takes a Trip … and All That. print ISBN 978-0-9928671-0-2 or online in Kindle format https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00KLOEOIO ISBN 978-0-9928671-1-9.

- Bray, Christopher (2014). 1965: The Year Modern Britain was Born. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-387-5.

- Levin, Bernard (1970). The Pendulum Years. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-61963-9.

- MacDonald, Ian (November 2002). "The Rolling Stones: Play With Fire". Uncut. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required)

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2016). The Rolling Stones All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. Running Press. ISBN 978-0316317733.

- Melly, George (1970). Revolt into Style. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-0166-5.

- Moon, Tom (2004). "The Rolling Stones". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. London: Fireside. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Norman, Philip (2001). The Stones. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-07277-6.

- Nuttall, Jeff (1968). Bomb Culture. MacGibbon & Kee. ISBN 978-0-261-62617-1.

- Sandbrook, Dominic (2006). White Heat: A history of Britain in the swinging sixties. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-72452-4.

- Sandbrook, Dominic (2005). Never Had It So Good: A history of Britain from Suez to the Beatles. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-86083-3.

- Salter, Tom (1970). Carnaby Street. Margaret and Jack Hobbs, Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, England. ISBN 978-0-85138-009-4.