Stephen MacKenna

Stephen MacKenna | |

|---|---|

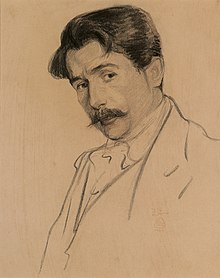

Drawing by Leo Mielziner, 1907 | |

| Born | 15 January 1872 Liverpool, England |

| Died | 8 March 1934 (aged 62) London, England |

| Occupation | Journalist, translator, linguist and author |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Notable works | English translation of Plotinus's Enneads |

Stephen MacKenna (15 January 1872 – 8 March 1934) was a journalist, linguist and writer of Irish descent. He is perhaps most well known for his important English translation of the Greek-speaking philosopher Plotinus (c. 204/5 – 270), introducing Neoplatonic philosophy to a new generation of readers.

MacKenna's prose style was widely admired and he influenced many of his contemporaries, including W. B. Yeats, W. B. Stanford and J. M. Synge.

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]

MacKenna was born 15 January 1872 in Liverpool, England[1] to an Irish father and an Anglo-Irish mother. His father, Captain Stephen Joseph MacKenna, served in the 28th Infantry in India and under Garibaldi in Italy. Returning to England, he wrote children's adventure stories and began to have a family.[2]

Growing up, MacKenna had seven brothers and two sisters. He and his brothers were educated at Ratcliffe in Leicestershire. It was there that he first acquired a knowledge of Classical Greek. MacKenna impressed with his literary talents, particularly in his personal translations of Virgil's Georgics and Sophocles' Antigone. He passed the Matriculation, but despite his talents he failed to pass the Intermediate: the university entrance examination.[2]

After a brief period as a novice in a religious order he became a clerk in the Munster & Leinster Bank. He then obtained a job as a reporter for a London newspaper, and in 1896 progressed to a post as Paris correspondent for a Catholic journal. It was in Paris in 1897 around the Hotel Corneille where he met Maud Gonne, Arthur Lynch and J. M. Synge.[3][4] Synge considered MacKenna his closest friend,[4][5] and Lynch later wrote,

The man who knew Synge best was Stephen MacKenna, and Synge's first book bears evident marks of MacKenna's influence or, as I should say perhaps, MacKenna's active help.[6][3][7]

In London he collected books, joined the Irish Literary Society and became a member of Young Ireland, a revolutionary group.

Culture and language interests

[edit]With the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, MacKenna rushed to join the Greek forces as a volunteer. This enabled him to acquire a command of colloquial Greek. It was here that his love for Greek, both ancient and modern, became active.[3] Years later, he would write,

I have vowed to give one half hour at least every day, at any cost, to reading Irish and modern Greek alternately. I cannot bear to think of not being able to read Gaelic fluently before I die, and I will not let modern Greek perish off my lips if only by way of homage to the ancient holy land and in the faint hope that someday, somehow, I may see it again with clearer eyes and richer understanding.[8]

His service was brief, and he returned first to Paris, then to London, and afterwards went on to Dublin. After a brief stay in New York, where he lived in poverty, he returned to Paris. He then obtained a job as European foreign correspondent with Joseph Pulitzer, reporting from as far afield as Russia and Hungary.

Around 1907 or 1908 he married Marie Bray (1878–1923),[9] an American born pianist educated in France. They shared similar cultural and political interests.

In the early 1900s MacKenna began to revise the Greek he had learned at school and to perfect his command of it. By 1905, he expressed an interest in translating the works of the Greek philosopher Plotinus, whose concept of a transcendent “One,” prior to all other realities, he found fascinating. He resigned from his job as a correspondent for Pulitzer, but continued to write for the Freeman's Journal, an Irish nationalist paper. In the meantime he published a translation of the first volume of Plotinus, Ennead 1.

MacKenna had already begun to acquire the rudiments of the Irish language. He and Marie had attended Gaelic League classes in London. In Dublin he did administrative work for the League and was keen to expand its activities. His house in Dublin was a centre of League activity, with enthusiasts meeting there once a week. His friend Piaras Béaslaí later testified that MacKenna learned to speak the language with reasonable fluency.[10] MacKenna had a high opinion of the capabilities of the language, saying "A man could do anything in Irish, say and express anything, and do it with an exquisite beauty of sound."[11] Poet Austin Clarke expressed awe regarding MacKenna's ability to use the Irish language:

[Mackenna spoke Irish] fluently and in a Dublin way. Once I listed for half an hour while Mrs. Alice Stopford Green, the historian, and he conversed so eagerly that it became a living language to me. Later he taught Irish to James Stephens, and to his enthusiasm and help we owe Reincarnations.[12]

MacKenna regretted that he had come to the language too late to use it as a medium of written expression, writing "I consider it the flaw and sin of my life that I didn't twenty years ago give myself body and soul to the Gaelic [i.e. Irish] to become a writer in it..."[11]

Irish nationalism

[edit]MacKenna was an ardent Irish nationalist and member of the Gaelic League.[13] He imagined a future where Ireland would be completely emancipated from all things English:

I do not know how Ireland is to be freed or built up: I do not know whether it ever can: all I know is that I cannot imagine myself happy in heaven or hell if Ireland, in its soul or in its material state, is to be always English.[14]

This vision of Ireland's future is why he opposed the Treaty.[13] He saw the outbreak of war in 1914 as disastrous for all sides and was deeply saddened by the violence. The Easter Rebellion of 1916 by militant Irish nationalists in Dublin took him by surprise, as it did for many in Ireland. He particularly mourned for his friend and neighbour, Michael O'Rahilly, who was wounded by machine gun fire in Moore Street and left to die over two days.

Later years and death

[edit]Both he and Marie suffered from failing health. Marie died in 1923, and MacKenna moved to England to increase his chances of recovery. He continued to translate and publish the work of Plotinus, with B.S. Page being a collaborator on the last volume. By this time he had privately rejected Catholicism.[15] His investigation of other philosophies and religious traditions drew him back to Plotinus and the intuitive perception of the visible world as an expression of something other than itself, the result of a "divine mind at work (or at play) in the universe."[16]

His income was greatly reduced and his last years were spent in a small cottage in Cornwall. Realizing that his death was approaching, he expressed he had no wish to live longer and had no fear of dying alone, instead preferring the prospect. By being alone, he would avoid the "black crows" who he expected would pester him with services once they found he was on his death bed. He both hoped and expected that there was nothing after death.[17]

In November 1933, MacKenna entered a hospital for operations to help with his failing health.[18] He was initially expected to recover, but eventually lost the endurance to live. He was true to his word and kept his whereabouts a secret from friends, planning to die alone. Only a few days before his death, however, Margaret Nunn discovered his address from his landlord at Reskadinnick and obtained permission to visit him. He died at Royal Northern Hospital[19] in London on 8 March 1934, aged 62.[20][21]

Translation of Plotinus

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Neoplatonism |

|---|

|

|

|

MacKenna's translation of Plotinus' Enneads was effectively his life's work, beginning in 1905 and finally finishing in 1930.

Throughout his life, Plotinus remained a significant influence. The deep connection he felt with the philosophy was expressed in a 1907 journal entry:

Whenever I look into Plotinus I feel always all the old trembling fevered longing: it seems to me that I must be born for him, and that somehow someday I must have nobly translated him: my heart, untravelled, still to Plotinus turns and drags at each remove a lengthening chain. It seems to me that him alone of authors I understand by inborn sight...[22]

Discovery and beginnings

[edit]Around 1905, while on a trip to St. Petersburg, MacKenna encountered Georg Friedrich Creuzer's Oxford text of Plotinus. Returning to Paris, he encountered the French translation by Didot.[23] He became enamored with Neoplatonic philosophy and desired to translate The Enneads in full.

In 1908, MacKenna released an initial rendering of the essay on Beauty (Ennead 1.6) which drew considerable respect from scholars.[24] Among the impressed was Dean Inge, who praised it for its clear and vigorous wording.[24] By 1912, this initial translation had garnered the attention of English businessman E. R. Debenham who subsequently provided MacKenna with material support for the completion of the work.[24]

Method

[edit]With the first version of the First Ennead, MacKenna declared his purpose and method for the translation:

The present translation has been executed on the basic ideal of carrying Plotinus' thought—its strength and its weakness alike—to the mind of the reader of English; the first aim has been the utmost attainable clearness in the faithful, full and unalloyed expression of the meaning; the second aim, set a long way after the first, has been the reproduction of the splendid soaring passages with all their warmth and light. Nothing whatever has been, consciously, added or omitted with such absurd purpose as that of heightening either the force and beauty demand a clarity which sometimes must be, courageously, imposed upon the most negligent, probably, of the great authors of the world.[25]

He based his translation on Richard Volkmann's 1883 text (published by Teubner), occasionally adopting a reading from Friedrich Creuzer's 1835 Oxford text.[26] He also compared his version to other language translations, including:[24]

- The Latin of Ficino (in Creuzer's edition)

- The French of M. N. Bouillet (three vols., Paris, 1875, &c.)

- The German of Hermann Friedrich Mueller (2 vols., Berlin: Weidmann, 1878–80)

- The German of Otto Kiefer (2 vols., Diederichs: Jena and Leipzig, 1905)

When B.S. Page made revisions on the fourth edition of MacKenna's translation, he utilized the Henry-Schwyzer critical edition, the Beutler-Theiler revision of Harder's German translation, and the first three volumes of A. H. Armstrong's Loeb translation.[24]

Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smooths there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiseling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine.

MacKenna rewrote sections of the translation, sometimes as many as three or four times.[27] While contemporary translations (including Armstrong's) have been more true to the original on a literal level, MacKenna's translation has been praised for its "stylistic qualities and beauty characteristics."[28]

It has been suggested that the influence of Plotinus can be seen in MacKenna's translation style, being drawn in particular from the essay concerning Beauty where Plotinus discusses the preparation of the soul for its ascent to the world of Nous and God (Ennead 1.6.9).[27] In Plotinus, the main interest of philosophy and religion "is the ascent of the soul to the realm of Nous."[29] MacKenna translated "Nous" here as "Intellectual Principle," while Dean Inge instead translated it as "Spirit."

Recognition and criticism

[edit]In 1924, Yeats announced at the Tailteann Games that the Royal Irish Academy had awarded a medal to MacKenna for the translation. MacKenna declined the award because of his distaste for connecting the English and Irish, declining membership to the Royal Irish Academy for similar reasons.[30] He explained his reasoning in a 1924 letter:

I couldn't accept anything from a society, or even from a Games, where the title or purpose is such as to play the old game of pretending that anything with any shreds of respectability flapping about its flanks is British or pro-British. The one pure spot in me is the passion for the purity of Ireland: I admire the English in England, I abhor them in Ireland; and at no time in more than 30 years of my emotional life... would I ever have accepted anything from Royal Societies or Gawstles or anything with the smell of England on it.[31]

E. R. Dodds praised MacKenna's translation, ultimately concluding that "[It] is one of the few great translations of our day... a noble monument to an Irishman's courage, an Englishman's generosity (Debenham's), and the idealism of both."[32] Sir John Squire similarly praised the translation, writing "I do not think that any living man has written nobler prose than Mr. MacKenna."[24] A reviewer in The Journal of Hellenic Studies wrote that "In the matter of accuracy, Mr. MacKenna's translation, which in English at least is pioneer work, is not likely to be final, but for beauty it will never be surpassed.[24]

Legacy

[edit]MacKenna's translation of Plotinus was discovered by Irish poet W. B. Yeats, whose own writing would subsequently be influenced greatly by the translation:[33]

Another little encouragement, Yeats, a friend tells me, came to London, glided into a bookshop and dreamily asked for the new Plotinus, began to read there and then, and read on and on till he'd finished (he really has a colossal brain, you know), and now is preaching Plotinus to all his train of attendant Duchesses. He told my friend that he intended to give the winter in Dublin to Plotinus.[34]

The Plato Centre at Trinity College Dublin holds the "Stephen MacKenna Lecture" annually in honour of MacKenna. The lecture series stated goal is "to bring distinguished contemporary scholars working in the area of Plato and the Platonic tradition to Dublin to deliver a lecture aimed at a wide and general audience."[35]

Literature

[edit]MacKenna's prose style was widely admired and he influenced many of his contemporaries,[36] including W. B. Yeats,[37] W. B. Stanford[38] and J. M. Synge.[3][6][7]

James Joyce paid tribute to him in chapter 9 ('Scylla and Charybdis') of his novel Ulysses, with the librarian Richard Best saying,

Mallarmé, don't you know, has written those wonderful prose poems Stephen MacKenna used to read to me in Paris.[39]

Writings

[edit]- trans., Plotinus [...] with Porphyry's Life of Plotinus, and the Preller-Ritter extracts, forming a conspectus of the Plotinian system, 5 vols. (Library of Philosophical Translations). London & Boston: The Medici Society Ltd., 1917–30.

- Journals and Letters (1936) ed. E. R. Dodds, with a memoir by Dodds (pp. 1–89) and a preface by Padraic Colum (pp.xi-xvii). London: Constable; NY: W. Morrow. 330pp.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Deane 1991, p. 155 ftn.

- ^ a b Murray 1937, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d Murray 1937, p. 195.

- ^ a b Saddlemyer 1964, p. 279.

- ^ Mathews 2009, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Lynch 1928, p. 131.

- ^ a b Mikhail 2016, p. 8.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Kelly 2003, p. 334.

- ^ Archived recording of a 1956 talk by Béaslaí about MacKenna on RTÉ Radio (Raidió na Gaeltachta): “Piaras Béaslaí ag caint ar Stiofán Mac Éanna sa bhliain 1956”: 20150831_rteraidion-siulachscealach-silachscal_c20839806_20839808_232_drm_ (1).

- ^ a b Dodds 1936, p. 37.

- ^ Deane 1991, p. 497.

- ^ a b Murray 1937, p. 198.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 131.

- ^ Dodds 1936, p. 65–66.

- ^ Dodds 1936, p. 69.

- ^ Dodds 1936, p. 88.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 321–22.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, pp. 321–24.

- ^ Dodds 1936, p. 89.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 324.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 114.

- ^ Murray 1937, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g Murray 1937, p. 192.

- ^ Murray 1937, p. 199.

- ^ MacKenna 1992, p. xvii.

- ^ a b Murray 1937, p. 201.

- ^ Uždavinys 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Murray 1937, p. 202.

- ^ Murray 1937, pp. 192–93.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 202.

- ^ Dodds 1936, p. 81.

- ^ Stanford 1976, p. 97.

- ^ MacKenna 1936, p. 235.

- ^ "Stephen MacKenna Lecture". www.tcd.ie. Plato Centre: Trinity College Dublin. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ Deane 1991, pp. 495–501.

- ^ Yeats 1999, p. 230.

- ^ Deane 1991, pp. 97, 198.

- ^ Joyce 1934, p. 185.

Sources

[edit]- Deane, Seamus (1991). The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing. Vol. 3. Derry: Field Day. ISBN 978-0-3930-3046-4.

- Dodds, E. R. (1936). "Memoir". In Dodds, E. R. (ed.). Journals and Letters of Stephen MacKenna. London: Constable & Company Ltd. pp. 1–89.

- Joyce, James (1934). Ulysses (First American ed.). New York: Modern Library Inc.

- Kelly, J. (2003). A W.B. Yeats Chronology. Springer. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-2305-9691-7. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Lynch, Arthur (20 October 1928). "Synge". The Irish Statesman. 11 (7): 131.

- MacKenna, Stephen (1936). Dodds, E. R. (ed.). Journals and Letters of Stephen MacKenna. London: Constable & Company Ltd.

- MacKenna, Stephen (1992). The Enneads: Extracts from the Explanatory Matter in the First Edition. Burdett, New York: Larson Publications. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-943914-55-8.

- Mathews, P. J. (2009). The Cambridge Companion to J. M. Synge. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-5211-1010-5. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- Mikhail, E. H. (2016). J. M. Synge: Interviews and Recollections. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-3490-3016-3. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Murray, John (1937). "Stephen MacKenna and Plotinus". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 26 (102): 190–206. JSTOR 30097402.

- Plotinus. The Six Enneads. Translated by Stephen Mackenna and B. S. Page: The Internet Classics Archive.

- Saddlemyer, Ann (1964). "Synge to MacKenna: The Mature Years". The Massachusetts Review. 5 (2): 279–296. JSTOR 25087101.

- Stanford, William Bedell (1976). Ireland and the Classical Tradition (1984 ed.). Irish Academic Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-7165-2361-1.

- Uždavinys, Algis (2009). The Heart of Plotinus: The Essential Eneads Including Porphyry's On the Cave of the Nymphs. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 978-1-9333-1669-7.

- Yeats, W. B. (1 March 1999). The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats Vol. III: Autobiographies. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-6848-5338-3.