Star system

A star system or stellar system is a small number of stars that orbit each other,[1] bound by gravitational attraction. A large group of stars bound by gravitation is generally called a star cluster or galaxy, although, broadly speaking, they are also star systems. Star systems are not to be confused with planetary systems, which include planets and similar bodies (such as comets).

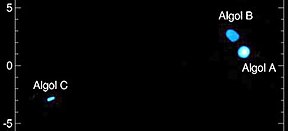

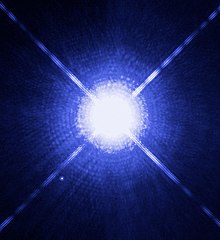

A star system of two stars is known as a binary star, binary star system or physical double star. If there are no tidal effects, no perturbation from other forces, and no transfer of mass from one star to the other, such a system is stable, and both stars will trace out an elliptical orbit around the barycenter of the system indefinitely.[citation needed] (See Two-body problem). Examples of binary systems are Sirius, Procyon and Cygnus X-1, the last of which probably consists of a star and a black hole.

Multiple star systems

[edit]A multiple star system consists of two or more stars that appear from Earth to be close to one another in the sky.[dubious – discuss] This may result from the stars actually being physically close and gravitationally bound to each other, in which case it is a physical multiple star, or this closeness may be merely apparent, in which case it is an optical multiple star[a] Physical multiple stars are also commonly called multiple stars or multiple star systems.[2][3][4][5]

Most multiple star systems are triple stars. Systems with four or more components are less likely to occur.[3] Multiple-star systems are called triple, ternary, or trinary if they contain 3 stars; quadruple or quaternary if they contain 4 stars; quintuple or quintenary with 5 stars; sextuple or sextenary with 6 stars; septuple or septenary with 7 stars; octuple or octenary with 8 stars. These systems are smaller than open star clusters, which have more complex dynamics and typically have from 100 to 1,000 stars.[6] Most multiple star systems known are triple; for higher multiplicities, the number of known systems with a given multiplicity decreases exponentially with multiplicity.[7] For example, in the 1999 revision of Tokovinin's catalog[3] of physical multiple stars, 551 out of the 728 systems described are triple. However, because of suspected selection effects, the ability to interpret these statistics is very limited.[8]

Multiple-star systems can be divided into two main dynamical classes:

- (1) hierarchical systems, which are stable, and consist of nested orbits that do not interact much, and so each level of the hierarchy can be treated as a Two-body problem

or

- (2) the trapezia which have unstable strongly interacting orbits and are modelled as an n-body problem, exhibiting chaotic behavior.[9] They can have 2, 3, or 4 stars.

Hierarchical systems

[edit]

Most multiple-star systems are organized in what is called a hierarchical system: the stars in the system can be divided into two smaller groups, each of which traverses a larger orbit around the system's center of mass. Each of these smaller groups must also be hierarchical, which means that they must be divided into smaller subgroups which themselves are hierarchical, and so on.[11] Each level of the hierarchy can be treated as a two-body problem by considering close pairs as if they were a single star. In these systems there is little interaction between the orbits and the stars' motion will continue to approximate stable[3][12] Keplerian orbits around the system's center of mass,[13] unlike the unstable trapezia systems or the even more complex dynamics of the large number of stars in star clusters and galaxies.

Triple star systems

[edit]In a physical triple star system, each star orbits the center of mass of the system. Usually, two of the stars form a close binary system, and the third orbits this pair at a distance much larger than that of the binary orbit. This arrangement is called hierarchical.[14][11] The reason for this arrangement is that if the inner and outer orbits are comparable in size, the system may become dynamically unstable, leading to a star being ejected from the system.[15] EZ Aquarii is an example of a physical hierarchical triple system, which has an outer star orbiting an inner physical binary composed of two more red dwarf stars. Triple stars that are not all gravitationally bound might comprise a physical binary and an optical companion (such as Beta Cephei) or, in rare cases, a purely optical triple star (such as Gamma Serpentis).

Higher multiplicities

[edit]

- multiplex

- simplex, binary system

- simplex, triple system, hierarchy 2

- simplex, quadruple system, hierarchy 2

- simplex, quadruple system, hierarchy 3

- simplex, quintuple system, hierarchy 4.

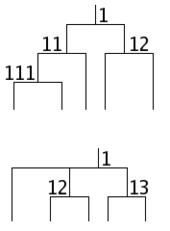

Hierarchical multiple star systems with more than three stars can produce a number of more complicated arrangements. These arrangements can be organized by what Evans (1968) called mobile diagrams, which look similar to ornamental mobiles hung from the ceiling. Examples of hierarchical systems are given in the figure to the right (Mobile diagrams). Each level of the diagram illustrates the decomposition of the system into two or more systems with smaller size. Evans calls a diagram multiplex if there is a node with more than two children, i.e. if the decomposition of some subsystem involves two or more orbits with comparable size. Because, as we have already seen for triple stars, this may be unstable, multiple stars are expected to be simplex, meaning that at each level there are exactly two children. Evans calls the number of levels in the diagram its hierarchy.[11]

- A simplex diagram of hierarchy 1, as in (b), describes a binary system.

- A simplex diagram of hierarchy 2 may describe a triple system, as in (c), or a quadruple system, as in (d).

- A simplex diagram of hierarchy 3 may describe a system with anywhere from four to eight components. The mobile diagram in (e) shows an example of a quadruple system with hierarchy 3, consisting of a single distant component orbiting a close binary system, with one of the components of the close binary being an even closer binary.

- A real example of a system with hierarchy 3 is Castor, also known as Alpha Geminorum or α Gem. It consists of what appears to be a visual binary star which, upon closer inspection, can be seen to consist of two spectroscopic binary stars. By itself, this would be a quadruple hierarchy 2 system as in (d), but it is orbited by a fainter more distant component, which is also a close red dwarf binary. This forms a sextuple system of hierarchy 3.[16]

- The maximum hierarchy occurring in A. A. Tokovinin's Multiple Star Catalogue, as of 1999, is 4.[3] For example, the stars Gliese 644A and Gliese 644B form what appears to be a close visual binary star; because Gliese 644B is a spectroscopic binary, this is actually a triple system. The triple system has the more distant visual companion Gliese 643 and the still more distant visual companion Gliese 644C, which, because of their common motion with Gliese 644AB, are thought to be gravitationally bound to the triple system. This forms a quintuple system whose mobile diagram would be the diagram of level 4 appearing in (f).[17]

Higher hierarchies are also possible.[11][18] Most of these higher hierarchies either are stable or suffer from internal perturbations.[19][20][21] Others consider complex multiple stars will in time theoretically disintegrate into less complex multiple stars, like more common observed triples or quadruples are possible.[22][23]

Trapezia

[edit]Trapezia are usually very young, unstable systems. These are thought to form in stellar nurseries, and quickly fragment into stable multiple stars, which in the process may eject components as galactic high-velocity stars.[24][25] They are named after the multiple star system known as the Trapezium Cluster in the heart of the Orion Nebula.[24] Such systems are not rare, and commonly appear close to or within bright nebulae. These stars have no standard hierarchical arrangements, but compete for stable orbits. This relationship is called interplay.[26] Such stars eventually settle down to a close binary with a distant companion, with the other star(s) previously in the system ejected into interstellar space at high velocities.[26] This dynamic may explain the runaway stars that might have been ejected during a collision of two binary star groups or a multiple system. This event is credited with ejecting AE Aurigae, Mu Columbae and 53 Arietis at above 200 km·s−1 and has been traced to the Trapezium cluster in the Orion Nebula some two million years ago.[27][28]

Designations and nomenclature

[edit]Multiple star designations

[edit]The components of multiple stars can be specified by appending the suffixes A, B, C, etc., to the system's designation. Suffixes such as AB may be used to denote the pair consisting of A and B. The sequence of letters B, C, etc. may be assigned in order of separation from the component A.[29][30] Components discovered close to an already known component may be assigned suffixes such as Aa, Ba, and so forth.[30]

Nomenclature in the Multiple Star Catalogue

[edit]

A. A. Tokovinin's Multiple Star Catalogue uses a system in which each subsystem in a mobile diagram is encoded by a sequence of digits. In the mobile diagram (d) above, for example, the widest system would be given the number 1, while the subsystem containing its primary component would be numbered 11 and the subsystem containing its secondary component would be numbered 12. Subsystems which would appear below this in the mobile diagram will be given numbers with three, four, or more digits. When describing a non-hierarchical system by this method, the same subsystem number will be used more than once; for example, a system with three visual components, A, B, and C, no two of which can be grouped into a subsystem, would have two subsystems numbered 1 denoting the two binaries AB and AC. In this case, if B and C were subsequently resolved into binaries, they would be given the subsystem numbers 12 and 13.[3]

Future multiple star system nomenclature

[edit]The current nomenclature for double and multiple stars can cause confusion as binary stars discovered in different ways are given different designations (for example, discoverer designations for visual binary stars and variable star designations for eclipsing binary stars), and, worse, component letters may be assigned differently by different authors, so that, for example, one person's A can be another's C.[31] Discussion starting in 1999 resulted in four proposed schemes to address this problem:[31]

- KoMa, a hierarchical scheme using upper- and lower-case letters and Arabic and Roman numerals;

- The Urban/Corbin Designation Method, a hierarchical numeric scheme similar to the Dewey Decimal Classification system;[32]

- The Sequential Designation Method, a non-hierarchical scheme in which components and subsystems are assigned numbers in order of discovery;[33] and

- WMC, the Washington Multiplicity Catalog, a hierarchical scheme in which the suffixes used in the Washington Double Star Catalog are extended with additional suffixed letters and numbers.

For a designation system, identifying the hierarchy within the system has the advantage that it makes identifying subsystems and computing their properties easier. However, it causes problems when new components are discovered at a level above or intermediate to the existing hierarchy. In this case, part of the hierarchy will shift inwards. Components which are found to be nonexistent, or are later reassigned to a different subsystem, also cause problems.[34][35]

During the 24th General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union in 2000, the WMC scheme was endorsed and it was resolved by Commissions 5, 8, 26, 42, and 45 that it should be expanded into a usable uniform designation scheme.[31] A sample of a catalog using the WMC scheme, covering half an hour of right ascension, was later prepared.[36] The issue was discussed again at the 25th General Assembly in 2003, and it was again resolved by commissions 5, 8, 26, 42, and 45, as well as the Working Group on Interferometry, that the WMC scheme should be expanded and further developed.[37]

The sample WMC is hierarchically organized; the hierarchy used is based on observed orbital periods or separations. Since it contains many visual double stars, which may be optical rather than physical, this hierarchy may be only apparent. It uses upper-case letters (A, B, ...) for the first level of the hierarchy, lower-case letters (a, b, ...) for the second level, and numbers (1, 2, ...) for the third. Subsequent levels would use alternating lower-case letters and numbers, but no examples of this were found in the sample.[31]

Examples

[edit]Binary

[edit]

- Sirius, a binary consisting of a main-sequence type A star and a white dwarf

- Procyon, which is similar to Sirius

- Mira, a variable consisting of a red giant and a white dwarf

- Delta Cephei, a Cepheid variable

- Almaaz, an eclipsing binary

- Spica

Triple

[edit]- Alpha Centauri is a triple star composed of a main binary Yellow dwarf and a Orange dwarf pair (Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman), and an outlying red dwarf, Proxima Centauri. Together, Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman form a physical binary star, designated as Alpha Centauri AB, α Cen AB, or RHD 1 AB, where the AB denotes this is a binary system.[38] The moderately eccentric orbit of the binary can make the components be as close as 11 AU or as far away as 36 AU. Proxima Centauri, also (though less frequently) called Alpha Centauri C, is much farther away (between 4300 and 13,000 AU) from α Cen AB, and orbits the central pair with a period of 547,000 (+66,000/-40,000) years.[39]

- Polaris or Alpha Ursae Minoris (α UMi), the north star, is a triple star system in which the closer companion star is extremely close to the main star—so close that it was only known from its gravitational tug on Polaris A (α UMi A) until it was imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006.

- Gliese 667 is a triple star system with two K-type main sequence stars and a red dwarf. The red dwarf, C, hosts between two and seven planets, of which one, Cc, alongside the unconfirmed Cf and Ce, are potentially habitable.

- HD 188753 is a triple star system located approximately 149 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Cygnus. The system is composed of HD 188753A, a yellow dwarf; HD 188753B, an orange dwarf; and HD 188753C, a red dwarf. B and C orbit each other every 156 days, and, as a group, orbit A every 25.7 years.[40]

- Fomalhaut (α PsA, α Piscis Austrini) is a triple star system in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. It was discovered to be a triple system in 2013, when the K type flare star TW Piscis Austrini and the red dwarf LP 876-10 were all confirmed to share proper motion through space. The primary has a massive dust disk similar to that of the early Solar System, but much more massive. It also contains a gas giant, Fomalhaut b. That same year, the tertiary star, LP 876-10 was also confirmed to house a dust disk.

- HD 181068 is a unique triple system, consisting of a red giant and two main-sequence stars. The orbits of the stars are oriented in such a way that all three stars eclipse each other.

Quadruple

[edit]

- Capella, a pair of giant stars orbited by a pair of red dwarfs, around 42 light years away from the Solar System. It has an apparent magnitude of around 0.08, making Capella one of the brightest stars in the night sky.

- 4 Centauri[41]

- Mizar is often said to have been the first binary star discovered when it was observed in 1650 by Giovanni Battista Riccioli[42], p. 1[43] but it was probably observed earlier, by Benedetto Castelli and Galileo.[citation needed] Later, spectroscopy of its components Mizar A and B revealed that they are both binary stars themselves.[44]

- HD 98800

- The PH1 system has the planet PH1 b (discovered in 2012 by the Planet Hunters group, a part of the Zooniverse) orbiting two of the four stars, making it the first known planet to be in a quadruple star system.[45]

- KOI-2626 is the first quadruple star system with an Earth-sized planet.[46]

- Xi Tauri (ξ Tau, ξ Tauri), located about 222 light years away, is a spectroscopic and eclipsing quadruple star consisting of three blue-white B-type main-sequence stars, along with an F-type star. Two of the stars are in a close orbit and revolve around each other once every 7.15 days. These in turn orbit the third star once every 145 days. The fourth star orbits the other three stars roughly every fifty years.[47]

Quintuple

[edit]Sextuple

[edit]- Beta Tucanae[51]

- Castor[52]

- HD 139691[53]

- TYC 7037-89-1[54]

- If Alcor is considered part of the Mizar system, the system can be considered a sextuple.

Septuple

[edit]Octuple

[edit]Nonuple

[edit]See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The term optical multiple star means that the stars may appear to be close to each other, when viewed from planet Earth, as they both seem to occupy nearly the same point in the sky, but in reality, one star may be much farther away from Earth than the other, which is not readily apparent unless one can view them over the course of a year, and observe distinct parallaxes.

References

[edit]- ^ A.S. Bhatia, ed. (2005). Modern Dictionary of Astronomy and Space Technology. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications. ISBN 81-7629-741-0.

- ^ John R. Percy (2007). Understanding Variable Stars. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-139-46328-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Tokovinin, A.A. (1997). "MSC - a catalogue of physical multiple stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 124: 75. Bibcode:1997A&AS..124...75T. doi:10.1051/aas:1997181.

online versions at

"online version at VizieR". Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

and at

A. Tokovin (ed.). "Multiple star catalog". ctio.noao.edu. - ^ "Double and multiple stars". Hipparcos. European Space Agency. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Binary and multiple stars". messier.seds.org. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ Binney, James; Tremaine, Scott (1987). Galactic Dynamics. Princeton University Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-691-08445-9.

- ^ Tokovinin, A. (2001). "Statistics of multiple stars: Some clues to formation mechanisms". The Formation of Binary Stars. 200: 84. Bibcode:2001IAUS..200...84T.

- ^ Tokovinin, A. (2004). "Statistics of multiple stars". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias. 21: 7. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..21....7T.

- ^ Leonard, Peter J.T. (2001). "Multiple stellar systems: Types and stability". In Murdin, P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics (online ed.). Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Nature Publishing Group published the original print edition.

- ^ "Smoke ring for a halo". Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d Evans, David S. (1968). "Stars of Higher Multiplicity". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 9: 388–400. Bibcode:1968QJRAS...9..388E.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. pp. 1. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Dynamics of multiple stars: observations Archived 19 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, A. Tokovinin, in "Massive Stars in Interacting Binaries", 16–20 August 2004, Quebec (ASP Conf. Ser., in print).

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. pp. 66–67. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Kiseleva, G.; Eggleton, P. P.; Anosova, J. P. (1994). "A note on the stability of hierarchical triple stars with initially circular orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 267: 161. Bibcode:1994MNRAS.267..161K. doi:10.1093/mnras/267.1.161.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. p. 72. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Mazeh, Tzevi; et al. (2001). "Studies of multiple stellar systems – IV. The triple-lined spectroscopic system Gliese 644". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 325 (1): 343–357. arXiv:astro-ph/0102451. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.325..343M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04419.x. S2CID 16472347.; see §7–8 for a discussion of the quintuple system.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. pp. 65–66. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Harrington, R.S. (1970). "Encounter Phenomena in Triple Stars". Astronomical Journal. 75: 114–118. Bibcode:1970AJ.....75.1140H. doi:10.1086/111067.

- ^ Fekel, Francis C (1987). "Multiple stars: Anathemas or friends?". Vistas in Astronomy. 30 (1): 69–76. Bibcode:1987VA.....30...69F. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(87)90021-3.

- ^ Zhuchkov, R. Ya.; Orlov, V. V.; Rubinov, A. V. (2006). "Multiple stars with low hierarchy: stable or unstable?". Publications of the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade. 80: 155–160. Bibcode:2006POBeo..80..155Z.

- ^ Rubinov, A. V. (2004). "Dynamical Evolution of Multiple Stars: Influence of the Initial Parameters of the System". Astronomy Reports. 48 (1): 155–160. Bibcode:2004ARep...48...45R. doi:10.1134/1.1641122. S2CID 119705425.

- ^ Harrington, R. S. (1977). "Multiple Star Formation from N-Body System Decay". Rev. Mex. Astron. Astrofís. 3: 209. Bibcode:1977RMxAA...3..209H.

- ^ a b Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. pp. 67–68. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Allen, C.; Poveda, A.; Hernández-Alcántara, A. (2006). "Runaway Stars, Trapezia, and Subtrapezia". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias. 25: 13. Bibcode:2006RMxAC..25...13A.

- ^ a b Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. p. 68. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ Blaauw, A.; Morgan, W.W. (1954). "The Space Motions of AE Aurigae and mu Columbae with Respect to the Orion Nebula". Astrophysical Journal. 119: 625. Bibcode:1954ApJ...119..625B. doi:10.1086/145866.

- ^ Hoogerwerf, R.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; de Zeeuw, P.T (2000). "The origin of runaway stars". Astrophysical Journal. 544 (2): 133–136. arXiv:astro-ph/0007436. Bibcode:2000ApJ...544L.133H. doi:10.1086/317315. S2CID 6725343.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 19. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ^ a b Format, The Washington Double Star Catalog Archived 12 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Brian D. Mason, Gary L. Wycoff, and William I. Hartkopf, Astrometry Department, United States Naval Observatory. Accessed on line 20 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d William I. Hartkopf & Brian D. Mason. "Addressing confusion in double star nomenclature: The Washington Multiplicity Catalog". United States Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "Urban/Corbin Designation Method". United States Naval Observatory. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "Sequential Designation Method". United States Naval Observatory. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ A. Tokovinin (18 April 2000). "On the designation of multiple stars". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ A. Tokovinin (17 April 2000). "Examples of multiple stellar systems discovery history to test new designation schemes". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ William I. Hartkopf & Brian D. Mason. "Sample Washington Multiplicity Catalog". United States Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Argyle, R. W. (2004). "A new classification scheme for double and multiple stars". The Observatory. 124: 94. Bibcode:2004Obs...124...94A.

- ^ Mason, Brian D.; Wycoff, Gary L.; Hartkopf, William I.; Douglass, Geoffrey G.; Worley, Charles E. (December 2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6). U. S. Naval Observatory, Washington D.C.: 3466–3471. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.3466M. doi:10.1086/323920.

- ^ Kervella, P.; Thévenin, F.; Lovis, C. (2017). "Proxima's orbit around α Centauri". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 598: L7. arXiv:1611.03495. Bibcode:2017A&A...598L...7K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629930. S2CID 50867264.

- ^ Does triple star orbit directly affect orbit time, Jeremy Hien, Jon Shewarts, Astronomical News 132, No. 6 (November 2011)

- ^ 4 Centauri Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, entry in the Multiple Star Catalog.

- ^ Robert Grant Aitken (2019). The Binary Stars. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-0-530-46473-2.

- ^ Vol. 1, part 1, p. 422, Almagestum Novum Archived 10 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Giovanni Battista Riccioli, Bononiae: Ex typographia haeredis Victorij Benatij, 1651.

- ^ A New View of Mizar Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Leos Ondra, accessed on line 26 May 2007.

- ^ "PH1 : A planet in a four-star system". Planet Hunters. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Ciardi, David. "KOI 2626: A Quadruple System with a Planet?" (PDF). nexsci.caltech.edu. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Nemravová, J. A.; et al. (2013). "An Unusual Quadruple System ξ Tauri". Central European Astrophysical Bulletin. 37 (1): 207–216. Bibcode:2013CEAB...37..207N.

- ^ Schütz, O.; Meeus, G.; Carmona, A.; Juhász, A.; Sterzik, M. F. (2011). "The young B-star quintuple system HD 155448". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 533: A54. arXiv:1108.1557. Bibcode:2011A&A...533A..54S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201016396. S2CID 56143776.

- ^ Gregg, T. A.; Prsa, A.; Welsh, W. F.; Orosz, J. A.; Fetherolf, T. (2013). "A Syzygy of KIC 4150611". American Astronomical Society. 221: 142.12. Bibcode:2013AAS...22114212G.

- ^ Lohr, M. E.; et al. (2015). "The doubly eclipsing quintuple low-mass star system 1SWASP J093010.78+533859.5". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 578: A103. arXiv:1504.07065. Bibcode:2015A&A...578A.103L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525973. S2CID 44548756.

- ^ "Multiple Star Catalog (MSC)". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Stelzer, B.; Burwitz, V. (2003). "Castor a and Castor B resolved in a simultaneous Chandra and XMM-Newton observation". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 402 (2): 719–728. arXiv:astro-ph/0302570. Bibcode:2003A&A...402..719S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030286. S2CID 15268418.

- ^ Tokovinin, A. A.; Shatskii, N. I.; Magnitskii, A. K. (1998). "ADS 9731: A new sextuple system". Astronomy Letters. 24 (6): 795. Bibcode:1998AstL...24..795T.

- ^ Md, By Jeanette Kazmierczak NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt. "Discovery Alert: First Six-star System Where All Six Stars Undergo Eclipses". Exoplanet Exploration: Planets Beyond our Solar System. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nu Scorpii Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, entry in the Multiple Star Catalog.

- ^ AR Cassiopeiae Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, entry in the Multiple Star Catalog.

- ^ Zasche, P.; Henzl, Z.; Mašek, M. (2022). "Multiply eclipsing candidates from the TESS satellite". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 664: A96. arXiv:2205.03934. Bibcode:2022A&A...664A..96Z. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243723. S2CID 248571745.

- ^ Hutter, D. J.; Tycner, C.; Zavala, R. T.; Benson, J. A.; Hummel, C. A.; Zirm, H. (2021). "Surveying the Bright Stars by Optical Interferometry. III. A Magnitude-limited Multiplicity Survey of Classical Be Stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 257 (2): 69. arXiv:2109.06839. Bibcode:2021ApJS..257...69H. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ac23cb. S2CID 237503492.

- ^ Mayer, P.; Harmanec, P.; Zasche, P.; Brož, M.; Catalan-Hurtado, R.; Barlow, B. N.; Frondorf, W.; Wolf, M.; Drechsel, H.; Chini, R.; Nasseri, A.; Pigulski, A.; Labadie-Bartz, J.; Christie, G. W.; Walker, W. S. G.; Blackford, M.; Blane, D.; Henden, A. A.; Bohlsen, T.; Božić, H.; Jonák, J. (2022). "Towards a consistent model of the hot quadruple system HD 93206 = QZ Carinæ — I. Observations and their initial analyses". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 666: A23. arXiv:2204.07045. Bibcode:2022A&A...666A..23M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142108. S2CID 248177961.

External links

[edit]- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Triple star system (11 September 2002)

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Alpha Centauri system (23 March 2003)

- Alpha Centauri, APOD, 2002 April 25

- General news on triple star systems, TSN, 2008 April 22 Archived 3 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- The Double Star Library Archived 15 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine is located at the U.S. Naval Observatory

- Naming New Extrasolar Planets