Stela of the cactus bearer

| Stela of the cactus bearer | |

|---|---|

Headstone with an anthropomorphic figure discovered in Chavín de Huántar in 1972. | |

| Material | Granite |

| Height | 80 cm |

| Width | 70 cm |

| Period/culture | 750 B.C.[1] |

| Discovered | November 14, 1972[2] in situ |

| Discovered by | Luis Guillermo Lumbreras |

| Present location | Circular Plaza, Chavín de Huántar, Huari Province, Department of Áncash, Peru |

| Registration | Headstone VI-NW12[3] |

| Culture | Chavín culture |

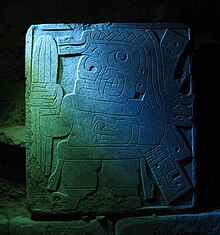

The stela of the cactus bearer is a monolith or stele of a single piece of granite, belonging to the Chavín culture of ancient Peru, which remains in its original location on the northwest side of the circular plaza at the archaeological site known as the ceremonial center of Chavín de Huántar in the Ancash region of Peru.[1][2] It was discovered during the 1972 excavation season by Peruvian archaeologist Luis Guillermo Lumbreras.

In 2001, a fragment of another stela was found in the circular plaza showing an exact mirror image of the stela of the cactus bearer. This fragment suggests that there were four stelae with this same representation: two in the northeast quadrant and two in the southeast quadrant, all facing the stairway leading to the gallery of the Lanzón de Chavín.[4]

The importance of this stela lies mainly in the fact that it is the clearest iconographic finding regarding the ancestral and ritual use of the Trichocereus macrogonus cactus in the Andes.[1][5] The presence of this entheogenic cactus in the Chavín lithic art located in one of the main structures of the ceremonial center has generated several interpretations about the function of the archaeological site.

Location

[edit]

The stela of the cactus bearer remains at its original location, that is, in the northwest quadrant inside the circular plaza at the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar. The site is located in the district of the same name, in the province of Huari, in the Ancash region.

The circular plaza is located in front of the building called "B", Old Temple or Ancient Temple.[6] It is semi-sunken with a depth of 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in), has two entrances (to the east and west) and has a diameter of 21 metres (69 ft).[7]

The cactus bearer's headstone was found in 1972 along with five other tombstones and it is estimated that in total there must have been 28 stelae of similar dimensions in the north and south quadrants of the west hemicycle of the plaza.[7]

The headstones found in the northwest quadrant show anthropomorphic beings walking as if in a procession, from right to left towards the east staircase, most of them carrying some object in their hands.[8]

Below that row of 80 cm × 70 cm (31 in × 28 in) headstones is another row of rectangular headstones measuring 36 cm × 69 cm (14 in × 27 in) with representations of felines with speckles, also advancing in the same direction as the beings represented in the upper row.[9]

Discovery and chronology

[edit]Discovery

[edit]The headstone was part of the discovery of the circular plaza by the team led by Peruvian archaeologist Luis Guillermo Lumbreras in the 1972 campaign, on November 14,[2] as part of the Chavín Archaeological Research Project carried out between 1966 and 1973.[10]

In 2001, during the excavation season of Stanford University's Chavín de Huántar Archaeological Research and Conservation Program led by archaeologist John W. Rick, a fragment of another stela was found in the circular plaza that shows an exact mirror image of the northwest quadrant cactus bearer stela. This fragment shows most of the individual's left leg, a hanging serpent descending from the individual's belt, and the lower structure of the cactus stem and root.[4]

The evidence found with the 2001 fragment suggests that the top row of headstones were also originally present in the southwest quadrant and that the slabs may have been matched pairs, totaling four stelae with the same representation: two facing right and two facing left, both facing the staircase descending westward from the Lanzón gallery.[11]

Chronology

[edit]The chronology of the site has been discussed throughout research for several decades. In 1989, Lumbreras placed the beginning of the Chavín culture in 1200 BC.[12] Then, in 2001, according to archaeologist John W. Rick and his team at Stanford University, the archaeological site as a cultural center would have begun its activities around 1500-1300 BC.[13][14][15] The latest research in 2019 by archaeologist and anthropologist Richard Burger of Yale University —based accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) analysis of bones obtained at the site— places the beginning of the occupation of Chavín de Huántar in 950 BC.[14]

There is consensus among researchers that the ceremonial center was built over several construction sequences. Some researchers establish three phases (based on radiocarbon dating in ceramic material), like Burger; others four phases and some even five, like Rick.[16][note 1] It is after the first construction phases when the circular plaza (with all its headstones), the gallery of the Caracoles, the gallery of the offerings and the east and west access stairs were added to the existing constructions —around 750 B.C.E.[9][18]

According to Burger's 2019 research, the construction of the circular plaza, its bas-relief headstones (including the cactus bearer stele) and associated galleries were developed in the second building phase called the Chakinani ceramic phase, from 800 to 700 B.C. This Chakinani phase is later than the first building phase called the Urabarriu ceramic phase, from 950 to 800 B.C., and earlier than the later building phase called the Janabarriu ceramic phase, from 700 to 400 B.C.[14]

Description

[edit]

Context

[edit]The stela is located in the circular plaza of the archaeological site, east of the Ancient Temple. This is a semi-sunken plaza with a depth of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in), a diameter of 21 m (69 ft) and two entrances to the west and east.[7] Of the six stelae found, five show anthropomorphic beings walking from right to left towards the east stairway, as if in procession.[8][19] It is interpreted that they are figures representative of members of the priestly caste of Chavín —including musicians and dancers[20]— that go in procession together with the jaguars (sculpted on the rectangular stelae in the lower frieze) towards the east stairway that leads to the gallery of the Lanzón, where the main stone sculptural representation of the temple is located: the Lanzón or great huanca of Chavín.[21]

Given this area is situated in front of the Lanzón gallery, located in the Ancient Temple, this structure within the archaeological monument was called the 'Lanzón atrium'.[22][6] The Lanzón atrium includes the circular plaza, the gallery of the Offerings, the gallery of the Caracoles, the east staircase (which goes from the circular plaza to the Lanzón gallery), and the west staircase.[23]

The cactus-bearer stela is considered to be part of a group of headstones engraved and originally located in the plaza: six found in 1972 and another 22 missing, giving a total of 28 headstones (fourteen for the northwest quadrant and fourteen for the southwest quadrant of the plaza). This was calculated on the basis of the dimensions of the stelae and the hemicycle.[7][24] Next to the cactus bearer stela, catalogued as headstone VI-NW12, the following stelae were found, from left to right:

- Headstone VI-NW6, in a very eroded state, but an anthropomorphic being can be distinguished in a position towards the front from which "a sort of rays appear to emanate from its four sides".[25]

- Headstone VI-NW7 ("trumpeter", 'pututero'), next to the personage on headstone VI-NW6, represents an anthropomorphic being in profile, walking towards the western stairway (or southwest stairway) holding a conch shell or pututo with their right arm and blowing it.[26]

- Headstone VI-NW8 ("trumpeter", 'pututero'), identical and contiguous to VI-NW7.[26]

- Headstone VI-NW9, very eroded, a personage in profile in an attitude of walking towards the western staircase with their right arm raised carrying an object (indistinguishable).[27]

Associated with the circular plaza and to the north side of it is the "gallery of the offerings". This gallery was initially excavated in 1966 and 1967 by Lumbreras and his team. They found more than 800 ceramic, stone, bone and shell artifacts, mostly broken. Thousands of broken bones of rodents, deer, camelids, canids, birds, fish and humans were also found. It has been interpreted that the artifacts and bones were placed as offerings in a great ritual event or great supracommunal feast.[28]

Located on the south side of the circular plaza, the gallery of the conch shells was also discovered in 1972. At that time, a large number of large fragments of Titanostrombus galeatus (formerly Strombus galeatus) seashells and Spondylus crassisquama (formerly Spondylus princeps) shells "arranged as if forming a floor", according to Lumbreras.[29] In 2001, in that same gallery, John Rick conducted excavations and found twenty shells (pututu in Quechua) sculpted in bas-relief.[30]

The stela

[edit]The stela shows an anthropomorphized being with serpent hair, a mouth with fangs or tusks, a belt with a two-headed serpent and claws, who in their right hand holds what appears to be a San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus, either var. macrogonus or var. pachanoi) with four veins or striations.[31][32]

Lumbreras' description of the headstone is as follows:[33]

"The personage does not have a human face, although it could have a mask, where the most outstanding element are thick fangs that exceed the lips of a mouth whose corner is quite large. The headgear is interesting; it does not have the aspect of a metallic crown of the first three stelae and could rather look like a turban or a braided hair that extends towards the back, where each one of the hairs becomes a snake. Both those above the forehead, as well as those that fall behind.

...

It also happens that the ears do not have earmuffs or earrings and that on the forehead the frown is noticeable and, finally, that the lips extend well beyond the mouth. The fangs are curved backwards and pointed, the other teeth are in block, like those of humans, except for those at the end of the mouth, where they bend the lips and are triangular and exempt. The pupil of the subrectangular eyes is eccentric and looks upwards. There are no eyebrows. From the neck hangs a pellegrina and at the waist there is a band from which hang two snakes. The nails of the hands and feet are 3 claws in the first and two in the second. He wears bracelets and armbands. The left hand is attached to the thorax and with the right hand holds the cactus. In the back there is an element similar to the "mantles" of which we speak with the musicians, but that well can be winged attributes".

— Luis Guillermo Lumbreras, Chavín: Excavaciones Arqueológicas I (2007)

Identification of the cactus species

[edit]It has been argued that the cactus depicted on the stela is the entheogenic cactus Echinopsis pachanoi a synonym for Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi. This variety of T. macrogonus, in common with another entheogenic Andean variety, T. macrogonus var. macrogunus[note 2] is commonly called the San Pedro cactus.[note 3] Apart from the bearer stela found by Lumbreras in 1972 and the stela fragment found by Rick in 2001, there are also two additional pieces found at Chavín with depictions of cacti:

- a miniature clava head recovered in 1935: three-veined cactus stems sprout from the eyes of the fanged anthropomorphic being;[21]

- a ceramic fragment with what appears to be the corona of a four-veined cactus in a Chavín-era midden in the Wacheqsa sector, where the Mosna and Huachecza rivers meet.[36]

From the same period known as the Early Horizon, ceramics and a textile with cactus representations have been found in the regions of Lambayeque and Ica.[1][37][38] In sites such as Tembladera and Cupisnique in the Lambayeque region, more than 32 ceramic representations of the San Pedro cactus have been found associated with spotted felines, snakes and birds of prey.[39][note 4]

Archaeobotanical remains of the San Pedro cactus have been found. The oldest find corresponds to that of the Guitarrero cave made by archaeologist Thomas F. Lynch in the Callejón de Huaylas, 120 km from Chavín de Huántar, dated to around 10,000 years before present.[41][42] Archaeologist Rosa Fung Pineda found remains of rolled bark that she assumes from the San Pedro cactus at the archaeological site of Las Aldas on the central coast in the Ancash region, occupied in the period 1200 to 900 BC.[43] In 2016 a group of archaeologists found this time a very well preserved cactus stem of the genus Echinopsis buried at Huaca El Paraíso in the Lima region dated to 2000 BC.[44]

Today, the cactus is the central element in the ritual practices of northern curanderismo, an expression of traditional medicine that takes place in the northwestern part of Peru, in the regions of Cajamarca, La Libertad, Lambayeque, Piura and Tumbes, and in southern Ecuador, in the province of Loja.[45][46][47][48]

Therefore, together with the evidence from ethnohistoric and ethnographic records, in addition to the presence of the cactus in the area in the wild, the researchers agree that the cactus represented on the bearer's stele is a San Pedro cactus, (Trichocereus macrogonus var. macrogonus, syn. Echinopsis peruviana; or T. macrogonus var. pachanoi, syn. Echinopsis pachanoi).[49][50]

Interpretations

[edit]It is commonly agreed that the different structures (buildings, plazas, stairways) of the archaeological site at Chavín de Huántar had mainly ceremonial functions and were associated with a religious cult.[51][52] Thus, the site is known today as the Chavín de Huántar ceremonial center.[53][54]

The circular plaza, therefore, was also a place for ritual activities. The floor of the plaza, after archaeological excavations, "has appeared remarkably clean, suggesting that it was a place cared for and maintained for singular activities."[55] Additionally, the center of the circular plaza aligns with a structure located on a hill to the east across the Mosna River exactly with the sunrise on the summer solstice each December, suggesting that there was a reason related to astronomical observation when this sector of the archaeological monument was designed.[note 5] This evidence strengthens the theory of the ritual function of the structure.[57]

Interpretations of the use of cactus in Chavín

[edit]

The representation of entheogenic plants in the cultural material found in the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar is solid with respect to the use of the San Pedro cactus.[59] Other evidence also suggests the ritual use of Anadenanthera colubrina (popularly known as vilca, cebil or willka, in Quechua), due to its possible representation not only on a stela, but also due to the finding of associated paraphernalia such as snuff tablets, vilcanas and spatulas.[60]

The use of cactus as a resource for manipulation

[edit]Archaeologist John W. Rick argued that "in the multiple media created or used —landscape, architecture, decoration, light, sound, drugs— I find evidence of finely tuned manipulation by site planners, executors, and orchestrators."[61] In this hypothesis, on the one hand, the representations of psychoactive plants on the stone stelae of the Chavín culture 3000 years ago are evidence of the manipulative use of entheogenic plants by cult members and, on the other hand, the Chavín temple was a place of psychological exploration and experimentation to test people's reactions to different stimuli.[62]

From that reasoning, Rick sees Chavín as a place constructed to impress and manipulate people in order to make them part of a religious belief system that serves the construction of authority and power of the cult members in relation to the populations in the local and regional context.[63]

The use of cacti as entheogens

[edit]Anthropologists and archaeologists George F. Lau and Richard Burger interpreted the temple not as a center designed for manipulation, but as a center of greater complexity, proposing the site of Chavín as an important pan-Andean center of a Late Formative product exchange network —tangible and intangible— and pilgrimage.[64][65][66][67] Burger also proposed that the seeds of Anadenanthera colubrina, not belonging to the ecosystems around Chavín, was one of the visionary plants that were part of this exchange, being brought to the archaeological site by pilgrims and traders from the lowland jungle.[60]

For Burger, the use of entheogens —substances with psychotropic properties used in religious contexts— is related to shamanism:[68]

In Chavín de Huántar, as in other places of religious power in ancient America, a central event in ritual activities was the ingestion of psychotropic substances. These hallucinogenic agents caused the transformative effect sought by priests and other religious officials in their quest for communication with the unseen powers that affected the natural world.

— Burger (1992): 271.

According to this perspective, the attributes of animals such as the jaguar (Panthera onca) or the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) in the sculptures of the Chavín culture are related to the alter egos of South American shamans.[69] In this sense, the presence of ceramics, metal plates, textiles and stelae such as that of the cactus bearer with attributes of felines, eagles and snakes is part of the religious message of shamanic transformation embodied in the architecture of the temple.[69]

-

Detail of the Raimondi stele.

-

Fragment of textile.

-

Gold embossed plate.

-

Clava head in the Chavin National Museum.

Interpretation of the character depicted on the stele

[edit]The anthropomorphic being represented on the stela has, as Lumbreras describes it, serpent, eagle and feline attributes. This would be the message of shamanic transformation to which Burger refers.[33][69] Likewise, given that the personage is carrying a San Pedro cactus in a ceremonial plaza, this fact accentuates the argument that "the cactus was integrated into the Chavín cult" and was used in the rituals.[70]

Anthropologist Leonardo Feldman Gracia interpreted that the stela of the bearer carries a visual metaphorical message related to the acquisition of animal attributes by the members of the Chavín cult; in the case of the jaguar: the eyes, mouth and nose of the personage, in the case of the snakes: the hair, and in the case of the bird of prey: the claws and wings.[72] Thus, according to Feldman Gracia, the cactus manages —by its psychotropic action— to amplify the perception and mental faculties of the person who ingests it:[73]

The eye of the feline, with an eccentric pupil, replaces that of the "bearer of St. Peter"; this metonymic substitution refers to the sensitization of sight and the opening of the capacity to "see". The substitution of human hair by snakes alludes to the sensitization of touch, it has been proven that St. Peter's produces a notable increase in the sensitivity of the skin; this "visual metonymy" expresses, then, that the priest acquires, in each pore, the tactile sensitivity of a snake.

Among the cenesthetic alterations produced by the San Pedro, the most common is the sensation of an extraordinary weightlessness in the body, the impression of levitating or flying. The unfolded wings, towards the back of the figure, should be interpreted as a metaphor of the referred kinesthesia.— Feldman Gracia (2006): 95–96.

Like Burger, Feldman Gracia argues that the use of the cactus must be considered under a double aspect. Not only does one acquire the attributes of animals by applying perception and mental faculties, but one also manages to enter into communion with the divinities and incarnate the mythical ancestors.[74] The Italian anthropologist Mario Polia —according to his ethnographic research in the Sierra de Piura— sees the ritual use of the San Pedro cactus also as a sacramental drink in the context of northern curanderismo: the ingestion of the cactus is a shamanic technique that allows the union of the shaman with the spiritual entity that resides in the plant.[75]

According to the above, then, the character engraved on the stela of the bearer would be representing a ritual specialist, a shaman, in full shamanic transformation: incorporating exceptional perceptions and faculties and, at the same time, in communion and communication with the divinities.[69] The latter is consistent with what Mircea Eliade mentions in his book Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy: "To incorporate an animal during the session is, as we have seen with regard to the dead, more than a possession, a magical transformation of the shaman into that animal".[76]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Rick's five constructive phases are: Mounds, Expansion, Consolidation, Black and White, and Support.[17]

- ^ Trichocereus macrogonus var. macrogonus was formerly more commonly known by the synonym Echinopsis peruviana.[34]

- ^ There are other cactus species also called San Pedro. Other entheogenic species present in the Andes known as 'San Pedro' include Echinopsis cuzcoensis and E. lageniformis.[35]

- ^ In 2000, the American anthropologist Douglas Sharon edited a book on Shamanism and the sacred cactus that included images of archaeological artifacts with representations of the cactus in lithic and ceramic material not only from the Early Horizon, but also from the Early Intermediate in the moche and nazca cultures.[40]

- ^ The celebration of the December solstice in the Andes is called Qhapaq Raymi.[56]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Samorini (2014, p. 19)

- ^ a b c Lumbreras (2007, p. 168)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007, p. 176)

- ^ a b Rick (2008b, p. 22)

- ^ Schultes & Hofmann (2010, p. 166)

- ^ a b Lumbreras (2014, p. 85)

- ^ a b c d González-Ramírez (2014, p. 137)

- ^ a b González-Ramírez (2014, p. 138)

- ^ a b González-Ramírez (2014, p. 139)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007, p. 13)

- ^ Rick (2008b, p. 23)

- ^ Burger (2019, p. 6)

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 9)

- ^ a b c Burger (2019, p. 13)

- ^ "Architectural Sequence and Chronology at Chavín de Huántar, Perú". www.kembel.com. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Burger (2019, pp. 2–6)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007), p. 77.

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 33)

- ^ Rick (2008b, p. 21)

- ^ Lumbreras (2014, pp. 97, 247)

- ^ a b Burger (2011, p. 124)

- ^ Iwasaki (1987, p. 19)

- ^ Lumbreras (2014, p. 125)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007, p. 175)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007, p. 179)

- ^ a b Lumbreras (2007, pp. 180–181)

- ^ Lumbreras (2007, p. 181)

- ^ Lumbreras (2014, p. 91)

- ^ Lumbreras (2014, pp. 89–90)

- ^ La Rosa, Rocío (19 August 2001). "Hallan en Perú instrumentos de 3000 años de antigüedad". La Nación (in Spanish). ISSN 0325-0946. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Sharon (2004, p. 62)

- ^ Morris, Hamilton (18 June 2012). "Desvelando los criptocactos" (in Spanish). Vice. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ a b Lumbreras (2007, pp. 182–183)

- ^ Albesiano & Kiesling (2012).

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006), p. 14.

- ^ Mesía Montenegro (2014, pp. 328–329)

- ^ Cordy-Collins (1982, p. 145)

- ^ Rick (2006, p. 106)

- ^ Torres (2008, p. 245)

- ^ Sharon (2000).

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 112)

- ^ Samorini, Giorgio (2019-06-01). "The oldest archeological data evidencing the relationship of Homo sapiens with psychoactive plants: A worldwide overview". Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 3 (2): 63–80. doi:10.1556/2054.2019.008.

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 29)

- ^ "Arqueólogos en Perú hallan un cactus de 4000 años". RTVE.es (in Spanish). EFE. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Polia Mecconi (1996, p. 330)

- ^ Pérez Villareal (2009, p. 90)

- ^ "Buscan declarar Patrimonio Cultural usos tradicionales de planta San Pedro" (in Spanish). Andina.com.pe. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Bussmann & Sharon (2015, p. 71)

- ^ Sharon (2000)

- ^ Torres (2008, pp. 241–243)

- ^ Rick (2008b, p. 20)

- ^ Lumbreras (2014, p. 156)

- ^ "Historia del Perú". educared.fundaciontelefonica.com.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Sitio Arqueológico de Chavín de Huántar Patrimonio Cultural" (in Spanish). Cátedra Unesco. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ González-Ramírez (2014, p. 700)

- ^ Ivan (2008).

- ^ Rick (2008b), p. 12.

- ^ González-Ramírez (2014, p. 132)

- ^ Rick (2013, p. 173)

- ^ a b Burger (2011, pp. 129–133)

- ^ Rick (2008a, p. 86)

- ^ Stanford University (25 April 2016). "Stanford archaeologist traces the origins of authority to the Andes of Peru". Stanford News. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Park, William (11 August 2016). "The Peruvian temple that hints at the origin of religion". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Lau (2016, p. 84)

- ^ Burger (1992, pp. 271, 277)

- ^ Burger (2019, pp. 15–16)

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 106)

- ^ Burger (1992, p. 271)

- ^ a b c d Burger (1995, p. 152)

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 42)

- ^ "Sculptural ceramic ceremonial vessel that represents a human face transforming into a feline face ML040218 - Cupisnique style". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, pp. 92–94)

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, pp. 95–96)

- ^ Feldman Gracia (2006, p. 96)

- ^ Polia Mecconi (1996, pp. 305–306)

- ^ Eliade (2009, p. 95)

Bibliography

[edit]- Albesiano, Sofía; Kiesling, Roberto (January 2012). "Identity and Neotypification of Cereus macrogonus, the Type Species of the Genus Trichocereus (Cactaceae)". Haseltonia. 17: 24–34. doi:10.2985/1070-0048-17.1.3.

- Burger, Richard L. (1992). Townsend, Richard F. (ed.). "Sacred Center at Chavín de Huántar". The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes. Chicago (United States): Art Institute of Chicago and Museum of Fine Arts (Houston): 265–277.

- Burger, Richard L. (1995). Chavín and the origins of Andean civilization (1st ed.). Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27816-4. OCLC 32704056.

- Burger, Richard L. (2011). "What kind of hallucinogenic snuff was used at Chavín de Huántar? An iconographic identification". Ñawpa Pacha. 31 (2): 123–140. doi:10.1179/naw.2011.31.2.123. ISSN 0077-6297. S2CID 191965354.

- Burger, Richard L. (2019). "Understanding the Socioeconomic Trajectory of Chavín de Huántar: A New Radiocarbon Sequence and Its Wider Implications" (PDF). Latin American Antiquity. 30 (2): 373–392. doi:10.1017/laq.2019.17. ISSN 1045-6635. S2CID 166501033.

- Bussmann, Rainer W.; Sharon, Douglas (2015). "Plantas Medicinales de los Andes y la Amazonía - La Flora mágica y medicinal del Norte del Perú". William L. Brown Center, Missouri Botanical Garden. St. Louis. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3485.0962. ISBN 978-0-9960231-3-9.

- Cordy-Collins, Alana (1982). "Psychoactive Painted Peruvian Plants: The Shamanism Textile" (PDF). Journal of Ethnobiology. 2 (2). San Diego: San Diego Museum of Man, University of San Diego: 144–153. ISSN 2162-4496.

- Eliade, Mircea (2009) [1968]. El chamanismo y las técnicas arcaicas del éxtasis (8th ed.). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Feldman Gracia, Leonardo (2006). El Cactus San Pedro : su función y significado en Chavín de Huántar y la tradición religiosa de los Andes Centrales (Master in social sciences thesis) (in Spanish). National University of San Marcos, Faculty of Social Sciences.

- González-Ramírez, Andrea (2014). Las Representaciones Figurativas como Materialidad Social - Producción y uso de las Cabezas Clavas de Chavín de Huántar (PhD thesis) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Department of Prehistory.

- Iwasaki, Fernando (1987). "Alucinógenos y religión Aproximaciones hacia el arte Chavín". Histórica (in Spanish). 11 (1). Lima: Department of Humanities of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP): 1–24. doi:10.18800/historica.198701.001. ISSN 0252-8894. S2CID 258860822.

- Lau, George F. (2016). An archaeology of Ancash : stones, ruins and communities in Andean Peru (in Spanish). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-48215-4. OCLC 948774131.

- Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo (2007), Chavín: Excavaciones Arqueológicas (1) (in Spanish), Lima: Universidad Alas Peruanas, ISBN 978-9972210310

- Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo (2014), Excavaciones en la plaza circular y el atrio del Lanzón de Chavín de Huantar (in Spanish), Lima: Instituto Andino de Estudios Arqueológicos - Sociales, ISBN 978-612-46332-3-2

- Mesía Montenegro, Christian (2014). "Festines y poder en Chavín de Huántar durante el período Formativo Tardío en los Andes centrales" (PDF). Chungará, Journal of Chilean Anthropology (in Spanish). 46 (3). Arica: University of Tarapacá: 313–343. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562014000300002. ISSN 0717-7356.

- Pérez Villareal, Ana María (2009). "Sistema médico tradicional con Sanpedro y la enseñanza a curanderos del maestro Marco Mosquera Huatay". Revista Cultura y Droga (in Spanish). 14 (16). Manizales: University of Caldas: 89–102. ISSN 0122-8455.

- Polia Mecconi, Mario (1996), "Despierta, remedio, cuenta...": adivinos y médicos del Ande (in Spanish), Lima: Editorial Fund of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, ISBN 9972-42-050-7

- Rick, John W. (2006). Sharon, Douglas (ed.). "Chavín de Huántar: Evidence for an Evolved Shamanism". Mesas & Cosmologies in the Central Andes: 101–112. ISBN 9780937808825.

- Rick, John W. (2008a). "The Evolution of Authority and Power at Chavín de Huántar, Peru". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 14 (1): 71–89. doi:10.1525/ap3a.2004.14.071.

- Rick, John W. (2008b). Conklin, William J.; Quilter, Jeffrey (eds.). Context, construction and ritual in the development of authority at Chavín de Huántar. Los Ángeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles. pp. 3–34. doi:10.2307/j.ctvdmwx21.7. ISBN 9781931745451.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Rick, John W. (2013). "Religion and Authority at Chavín de Huántar". Chavín: Peru's Enigmatic Temple in the Andes. Rietberg: Verlag Scheidegger and Spiess: 166–175. ISBN 9783858817310.

- Samorini, Giorgio (2014). "Aspectos y Problemas de la Arqueología de las Drogas Sudamericanas" (PDF). Revista Cultura y Droga (in Spanish). 21. Manizales: Maestría en Cultura y Droga, Universidad de Caldas: 13–34. doi:10.17151/cult.drog.2014.19.21.2 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0122-8455.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (2010). Plantas de los Dioses, Orígenes del Uso de los Alucinógenos (in Spanish). México D. F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 9789681663032.

- Sharon, Douglas (2000). Chamanismo y el cactus sagrado: evidencia etnoarqueológica para el uso de San Pedro en el norte de Perú [Shamanism and the sacred cactus: Ethnoarchaeological evidence on the use of the San Pedro cactus in northern Peru] (in Spanish). Museo del Hombre de San Diego.

- Sharon, Douglas (2004) [1978], El Chamán de los Cuatro Vientos (in Spanish), México D. F.: Siglo XXI Editores, ISBN 9789682310065

- Torres, Constantino Manuel (2008). Conklin, William J.; Quilter, Jeffrey (eds.). Chavin's Psychoactive Pharmacopeia: The Iconographic Evidence. Monograph 61. Los Ángeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles. pp. 239–259. doi:10.2307/j.ctvdmwx21.15. ISBN 978-1-931745-45-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Watson, Peter (2012). The Great Divide: History and Human Nature in the Old World and the New. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-29785857-7.

Websites

[edit]- Ivan, Ignacio (22 December 2008). "Mundo: ¿Qué Celebramos? ¿Qhapaq Raymi o Navidad? ¿Inti Raymi o San Juan?". Servindi (in Spanish). Servindi - Servicios de Comunicación Intercultural. Retrieved 4 May 2021.