St Mary's Church, Higham Ferrers

| St Mary's Church | |

|---|---|

The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin | |

| |

| 52°18′23″N 0°35′29″W / 52.30645°N 0.59135°W | |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Anglo-Catholic |

| Website | stmaryhighamferrers |

| History | |

| Founder(s) | Henry III of England |

| Dedication | St. Mary |

| Dedicated | c. 1220 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 23 September 1950 |

| Architectural type | Perpendicular Gothic |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Diocese of Peterborough |

| Parish | Higham Ferrers |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Rev Louise Bishop[1] |

St Mary's Church is a Church of England parish church in Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire. It is a Grade I listed building.

History and description

[edit]

The present church was founded by a charter of King Henry III in about 1220, with the tower being completed in about 1250.[2] A large proportion of the original church survives. The next phase of building, in about 1320, was the widening of the north aisle and the replacement of the nave arcade, to allow for the insertion of the Lady Chapel. Additional windows were added to the chancel and the south aisle. The clerestory and the low pitched roof, with parapets, is from the early 15th century, possibly under the auspices of Bishop Henry Chichele, later Archbishop of Canterbury. Chichele also had the rood screen and choir stalls with their misericords installed in about 1425. Archbishop Chichele also had All Souls College, Oxford built, and there is a resemblance between both sets of misericords, it is possible that the same carver, possibly Richard Tyllock, created both.

In 1631, the spire and part of the tower collapsed, and were repaired shortly afterwards.[3] This was the last work performed on the fabric of the church. Simon Jenkins, in his England's Thousand Best Churches, describes the spire as "one of the finest in a county famous for spires"[4] Two restorations took place during the 19th century, but both seem to have been sympathetically performed. The spire is 174 feet (53 m) high. [5] The tower contains a ring of ten bells, the previous eight having been restored and rehung in a new frame, together with two new bells, in 2014 by John Taylor & Co, Loughborough, the project marking the 600th anniversary of Henry Chichele's consecration as Archbishop of Canterbury. 167 full peals were rung on the eight bells and thirty three have now been rung on the ten, one being in a new "method", Regnum Diutissime ("the longest reign") Delight Royal in honour of the Queen having become the longest-reigning British monarch.[citation needed]

The west porch was built between 1270 and 1280. It is almost certainly the work of one of the foreign masons employed in the rebuilding of Westminster Abbey, the style and quality of the work here closely resembling the porch of the North transept of the Abbey.[6] Simon Jenkins, awarding St Mary's three stars, says:

The west front of the tower is little short of sensational, a gallery of medieval decoration attributed to French masons from Westminster. The twin doors are framed with carvings and a Tree of Jesse rising from a central shaft. The unusual roundels in the tympanum, based on illuminated manuscripts, are of New Testament scenes. Sculpture dots each front, including on the north a charming man making music while locked in the stocks. Some of the niches have excellent modern statues in them.[4]

Memorials

[edit]One of the earliest examples in England, the elaborate memorial brass to Laurence St. Maur, (died 1337) is considered by Pevsner to be one of the finest brass monuments in England. Originally on the chancel floor, it was placed on an altar tomb, between the two chancels, in 1633. St. Maur wears a heavily embroidered liturgical vestment and around his neck is a rectangle of cloth embroidered with cinquefoils.[7]

Above the main figure in the canopy is a group of figures. Abraham is seated in the middle and holds a globe in his left hand, with his right hand raised in benediction. St. Andrew and St. Peter are to the left of him and the St. Paul and St. Thomas are to the right. Angels, on either side of Abraham, hold St. Maur's soul.[8] In his 1912 book Brasses, John Sebastian Marlowe Ward says: "Canopies over Mass priests are very rare and this is by far the finest."[9]

Bede House and Chantry Chapel

[edit]Adjacent to the church, at the west, is the Chantry Chapel, also a Grade I listed building. Built in the early 15th century for Archbishop Chichele, it was restored in the 20th century by Temple Moore. It is of limestone ashlar with lead roof. It was used as a Grammar School from 1542 to 1906 and was re-dedicated as a chantry chapel in 1942.[10] To the south of the church, across the churchyard, is the bede house, also Grade I listed. Built in about 1428, it was restored in the 19th century. It is of squared coursed and banded limestone and ironstone, with a plain tile 20th-century roof. It is now used as the church hall.[11] The chantry chapel and Bede House, both Perpendicular Gothic in style, are open to the public.[4]

The stone cross in the churchyard, also Grade I listed, was known in 1463 as the Wardeyn or Warden Cross. It lies 48 metres (52 yd) west of the church tower and is believed to be medieval in origin, with later additions. It was restored in 1919 as a war memorial.[12][13]

Rectors and vicars

[edit]- 1238–1239: Master Hubert de Cotmanmeston

- 1268–1275: Roger de St Philibert

- 1275–1289: Master Robert de Hanneya

- 1289–1335: Lawrence de Sancto Mauro

- 1335–1337: Prebendary of Hinton

- 1337–1346: Master Henry de la Dale

- 1346: John Paynell

- Richard de Melburn

- 1350–1357: John de Stafford

- 1357–1358: William Mildrithe of Knyghton

- 1361–1363: Robert Hardegray

- 1363–1366: Henry Wakeries

- 1369–1374: John Godinche

- 1374–1387: Henry Knot

- 1387–1388: John Benethon de Wolaston

- 1404–1414: John Halleswayne

- 1414–1415: Henry de Bilburgh

- 1415–1416: John Bradbourne

- 1422–1429: William Moyes

- 1429–1430: Elias Holcote

- 1437–1438: William More

- 1438–1444: Warden of Merton

- 1444–1461: Richard Whyte

- 1461–1465: Thomas Rudde

- 1465–1469: William Blankeney

- 1469–1482: John Ward

- 1482–1487: William Bryan

- 1487–1488: John Frende

- 1492–1504: Richard Chauncellor

- 1504–1523: Richard Wylleys

- 1523–1534: William Fawntleroy

- 1534–1542: Robert Goldson

- 1542–1597: (no rector: church served by a series of curates)

- 1597–1599: Clement Gregory

- 1605–1631: Nichols Leonard

- 1631–1635: John Hill

- 1635–1645: John Digby

- 1647–1658: Henry Pheasant

- 1662-1662: ? Harrison

- 1662–1676: John Knighton

- 1676–1691: Samuel Lee

- 1691–1726: Richard Willis

- 1726–1730: John Glassbrook

- 1730–1735: William Doyly

- 1735–1740: George Tymms

- 1740–1745: Thomas Bright

- 1745–1752: William Withers

- 1752–1761: Francis Greenwood

- 1762–1802: George Pasley Malim

- 1803–1830: George Warcup Malim

- 1830–1837: Thomas Wentworth Gage

- 1837–1868: George Malim

- 1868–1885: Edward Templeman

- 1885–1889: George Hamslip Hopkins

- 1889–1906: James Dunn

- 1906–1911: Gerard Marby Davidson

- 1911–1923: Herbert Kearsley Fry

- 1923–1933: Basil Eversley Owen

- 1933–1945: Philip Kirk

- 1945–1952: Harold Stanley Hoar

- 1952–1964: Cecil Stafford Ford

- 1965–1988: Roger William Davison

- 1988–1997: Eric Buchanan

- 1998–2013: Grant Lindley Brockhouse

- 2014–2019: Richard Stainer

- 2023– : Louise Suzanne Bishop

Gallery

[edit]-

The east end

-

Graveyard cross and tower

-

The tower

-

Lower niche statue, tower

-

Typanum, east porch

-

The clock

-

Misericord

-

Tabernacle, Lady Chapel Altar

-

Screen from north aisle

-

Stoup

-

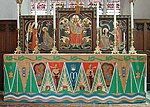

High Altar

-

South chapel ceiling

-

North aisle sanctuary

-

The belfry

-

The Bede House

-

The Chantry Chapel

References

[edit]- ^ "Home". Smhf.

- ^ The Buildings of England; Northamptonshire. Nikolaus Pevsner.

- ^ "CHURCH OF ST MARY, Higham Ferrers – 1191957 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Jenkins, S. (2000), England's Thousand Best Churches, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-103930-5, pp. 572–573.

- ^ Flannery, Julian (2016). Fifty English Steeples: The Finest Medieval Parish Church Towers and Spires in England. New York City, New York, United States: Thames and Hudson. pp. 206–217. ISBN 978-0-500-34314-2.

- ^ The Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a short guide. Revd. C. S. Ford, 1958

- ^ "Brass Rubbing: Laurence de St. Maur (Seymore), Search the Collection, Spurlock Museum, U of I". www.spurlock.illinois.edu.

- ^ "Laurence St. Maur Brass – Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire,". professor-moriarty.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Ward, J.S. M., (2012) Brasses, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-64090-0, (first published 1912), p.89 and p.163

- ^ Historic England. "Chantry Chapel of All Souls (Grade I) (1040359)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "Bede House (Grade I) (1191999)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ "The borough of Higham Ferrers". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "Churchyard cross in St Mary the Virgin churchyard (Grade I) (1016322)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2024.