Sol White

| Sol White | |

|---|---|

| |

| Second baseman / Manager | |

| Born: June 12, 1868 Bellaire, Ohio, U.S. | |

| Died: August 26, 1955 (aged 87) Central Islip, New York, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| debut | |

| 1887, for the Pittsburgh Keystones | |

| Last appearance | |

| 1926, for the Newark Stars (coach) | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

Negro league baseball

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 2006 |

| Election method | Committee on African-American Baseball |

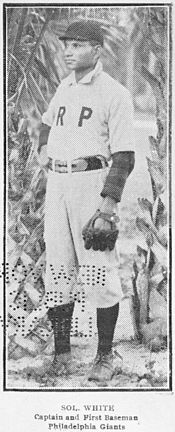

King Solomon "Sol" White (June 12, 1868 – August 26, 1955) was an American professional baseball infielder, manager and executive, and one of the pioneers of the Negro leagues. An active sportswriter for many years, he wrote the first definitive history of black baseball in 1907. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Early life

[edit]Born in Bellaire, Ohio, White's early life is not well-documented. According to the 1870 and 1880 U.S. Census, his family (parents and two oldest siblings) came from Virginia. His father, Saul Solomon White, apparently died when White was very young. White's mother, Judith, supported Sol and four siblings with her work as a "washer woman."[4] White "learned to play ball when quite a youngster."[5]

Playing career

[edit]As a teenager White was a fan of the Bellaire Globes, local amateurs. The journalist Floyd J. Calvin recounts the story of how White got a chance to play for his team. The Globes were playing a team from Marietta, Ohio. "One of the Globes players got his finger smashed and since they all knew Sol, the captain pushed him into the game. Sol always remembered that game for the captain and second baseman of the Marietta team was none other than Ban B. Johnson, in later years president of the American League and a leading sportsman of the West. Sol takes pride in having played against Ban when he was an obscure captain of a hick town club."[6]

White quickly made a name for himself as a ballplayer. By the time he was 16, he "attracted the attention of managers of independent teams throughout the Ohio Valley and his services were in great demand."[5] Originally a shortstop, White eventually "developed into a great all-round player filling any position from catcher to right field."[7] In 1887 he joined the Pittsburgh Keystones of the National Colored Base Ball League[1] as a left fielder and later second baseman. He was batting .308 when the league folded after a week of play.[8] He then joined the Wheeling (West Virginia) Green Stockings of the Ohio State League and batted .370 with a slugging percentage of .502 as the team's third baseman.

In the off-season the Ohio State League renamed itself the Tri-State League and banned black players, including White. Weldy Walker, an African American catcher for the league's Akron club, wrote an eloquent open letter to league officials protesting the decision. It was published in the Sporting Life in March 1888, and within a few weeks the ban was rescinded.[9][10] White was resigned and sent to join his team on the road, but the Wheeling manager, Al Buckenberger, refused to accept him, and he was released.[11] He rejoined the Pittsburgh Keystones, and played in a "Colored Championship" tournament held in New York City, in which the Keystones finished second to the Cuban Giants.[12]

White spent 1889 with the New York Gorhams, a black team that spent part of the season in the Middle States League.[13] White played both catcher and second base for the Gorhams.[14] The next year, he joined the York Colored Monarchs of the Eastern Interstate League, a white-owned team that signed up most of the 1889 Cuban Giants. White played second base, hit .350, and stole 21 bases in 54 games. In 1891 he played for the Big Gorhams of New York, a team that he later called "without a doubt one of the strongest teams ever gotten together, white or black."[15] The Gorhams briefly represented Norwalk, Connecticut, in the Connecticut State League.[16]

In 1895 White batted .385 as a second baseman for Fort Wayne, Indiana of the Western Interstate League.[8] Later that year, White replaced Bud Fowler at second base on the barnstorming Page Fence Giants team, batting .404 as the Giants finished with a 118-36-2 record and played in 112 towns in 7 states.[17]

White enrolled in Wilberforce University as a theology student in 1896, spending the next four years alternating between professional baseball with the Cuban X-Giants in the summer and college in the fall and winter.[18][19] He was still listed as an athletic instructor at Wilberforce in 1900.[2]

After a year as shortstop for the Chicago Columbia Giants in 1900 and one last season with the Cuban X-Giants in 1901, White moved to Philadelphia where he co-founded the Philadelphia Giants. His playing time was gradually curtailed as he concentrated on management.

According to research by Bob Davids, White spent all or part of five seasons in organized minor leagues, playing 152 games and hitting .359 with 169 runs scored, 231 hits, 40 doubles, and 41 stolen bases.[20]

Managerial career

[edit]

Along with Walter Schlichter, a sportswriter for the Philadelphia Item, and Harry Smith, a baseball writer for the Philadelphia Tribune, White founded the Philadelphia Giants in 1902. He served as the team's captain and manager. The Giants were at first paid on a profit-sharing "cooperative plan," but in 1903 White reorganized the team and put all the players on salary.[6] The Giants lost a playoff for the colored championship to the Cuban X-Giants and their ace pitcher, Rube Foster. The following season White signed Foster, outfielder Pete Hill, and second baseman Charlie Grant, and the Philadelphia Giants won a championship series from the X-Giants, five games to two.

For 1905 White brought in Home Run Johnson of the X-Giants, and made the Philadelphia Giants into what he considered "the strongest organization of the time." The Giants went undefeated against New England League teams and swept four games from the Newark International League team.[6] The Giants played a total of 158 games, winning 134, losing 21, and tying 3.[21] The powerful baseball promoter and team owner Nat Strong declared the 1904-1905 Philadelphia Giants "the best team in the history of the game."[22]

Despite losing Johnson to the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1906, the Giants won both the informal "colored championship" and the pennant of the racially integrated International League of Independent Professional Base Ball Clubs. More player losses followed in 1907, as Rube Foster defected to the Leland Giants of Chicago. But White brought in eventual Hall of Famer John Henry Lloyd to play shortstop along with catcher Bruce Petway, and the Giants finished first in the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs of the United States and Cuba, an all-black league. This marked the fourth consecutive year in which the Philadelphia Giants claimed the black professional championship.[23]

The Giants lost Pete Hill to the Lelands in 1908, and in 1909 Sol White left the team after a disagreement with Schlichter.[24] White managed the Philadelphia Quaker Giants for a year. In 1910 he was hired to manage the Brooklyn Royal Giants, but had trouble controlling some of the players, and left after the season.[25] For the following season Jess McMahon and his brother Eddie hired White to manage their new team, the New York Lincoln Giants. White assembled another collection of top players, including John Henry Lloyd, Spot Poles, and Bill Francis. In July 1911 he raided his old team, the Philadelphia Giants, for their star rookie battery, Dick Redding and Louis Santop. As a result, Schlichter could no longer keep the team running, and disbanded it.[26] However, White quit the Lincolns before the season was over, replaced as manager by Lloyd.[27]

White was next hired to manage the Fe club of the Cuban League for the 1911-12 winter season. He brought along Rube Foster and a number of American black players, but the team lost five of its first six games, and White and most of his players were released.[27][28] After a year managing an obscure team called the Boston Giants, White retired from baseball, and returned to Bellaire.[6]

He returned to baseball to serve as secretary for the Columbus Buckeyes of the Negro National League in 1921, and helped bring in his old player, John Henry Lloyd, as player-manager. White then took on his last two managerial jobs, both in Cleveland: in 1922 he guided an independent club, the Fears Giants of Cleveland, and in 1924 he managed the Cleveland Browns of the Negro National League.[29][30] His last job in baseball was as a coach for the 1926 Newark Stars of the Eastern Colored League.[31]

Negro league writings

[edit]

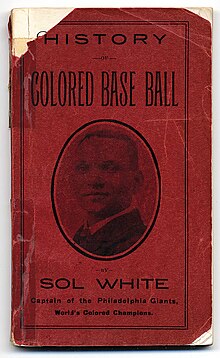

Sol White is perhaps best known for writing History of Colored Base Ball, also known (on the title page) as Sol White's Official Base Ball Guide. A small, 128-page, soft-covered pamphlet, History of Colored Base Ball was sold at Philadelphia Giants games in the spring of 1907.[32][33]

The first chapter, "Colored Base Ball," begins with the organization in 1885 of the first professional colored baseball team, discusses the brusque removal of all black players from predominantly white teams during the next four years, and then traces the growing strength of "colored base ball" into the early years of the 20th century. This short book-within-a-book is history, but it can also be described as an almanac, a scorecard, an archive, a who's who of African-American baseball up to 1907.

In addition to White's narrative of the history of black professional teams, the book featured chapters on "Colored Baseball as a Profession," "The Color Line," and "Managers' Troubles," among others. Rube Foster, one of White's former players, contributed a chapter on "How to Pitch," and Home Run Johnson wrote a short essay on the "Art and Science of Hitting." The book was also illustrated with 57 photographs of players, manager, and owners, many of them found nowhere else.[33]

White's History of Colored Base Ball was the first book devoted to black professional baseball, and it would remain the only one for more than 60 years, until Robert W. Peterson published Only the Ball Was White in 1970. Today only five copies are known to exist.[34]

Sol White's career as a baseball writer would continue with a series of articles on "colored baseball" in the Cleveland Advocate, a black newspaper, in 1919.[35] After he moved to the east coast in the 1920s he wrote articles and columns for the New York Age and the New York Amsterdam News.

In 1927 the Pittsburgh Courier reported that White "has a new book he would like to publish, a kind of second edition to his old one, bringing the game from 1907 down to date, and if there is anybody anywhere in sports circles who thinks enough of what has gone before to help Sol print his record, he will be glad to hear from them. Without a doubt this record will prove valuable in years to come." This second book on black baseball by Sol White never appeared.[6]

Personal life

[edit]Sol White married Florence Fields on March 15, 1906. Their first child, a son named Paran Walter White (named after Sol's older brother), was born later that year. A second son, a boy, died when he was only two days old in August 1907. Paran died of kidney disease in April 1908. A third child, a daughter named Marion, lived to adulthood and survived her father. Florence and Sol White appear to have become separated at some point before 1930.[36]

When White was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, no family member was present, so Commissioner of Baseball Bud Selig accepted his plaque on the family's behalf.[36]

In September 2024 an Ohio Historical Marker was placed in Bellaire, Ohio at the city park, Union Square, to remember the town's native son.

Death

[edit]White died at age 87 in Central Islip, New York. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Frederick Douglass Memorial Park in the Oakwood neighborhood of Staten Island, New York City, until 2014, when the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project installed a new headstone at his burial site. He remains the only Hall of Famer buried on Staten Island.[37][38]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Genuine Cuban Giants" The Evening Times, Washington, DC, Saturday, May 23, 1896, Page 3, Column 5

- ^ a b "The Columbia Giants of Chicago" Indianapolis Freeman, Indianapolis, IN, Saturday, March 24, 1900, Page 7, Column 1

- ^ "Giants Were Twice Defeated" The Patriot, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Friday, September 11, 1903, Page 7, Columns 1 and 2

- ^ White 2014, p. xii

- ^ a b White 1995, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Calvin, March 12, 1927.

- ^ White 1995, p.5.

- ^ a b Riley 1994, p. 836.

- ^ Walker, March 14, 1888.

- ^ White 1995, pp. 79-81.

- ^ White 2014, p. xiv.

- ^ White 1995, p. 16

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 98.

- ^ White 1995, p. 5

- ^ White 1995, p. 20.

- ^ Lomax 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Riley 1994, pp. 596, 836.

- ^ Hurd, October 7, 2011.

- ^ White 1995, p.5

- ^ White 1995, p. 161.

- ^ White 2014, p. 92

- ^ Wilson, January 16, 1926.

- ^ White 2014, p. xviii.

- ^ White 2014, pp. xviii-xix.

- ^ White 2014, p. xix.

- ^ Walton, August 3, 1911.

- ^ a b White 2014, p. xx.

- ^ Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database, 1911–12 Fe

- ^ Holway, p. 7

- ^ White 2014, p. xxi-xxii.

- ^ White 2014, p. xxii.

- ^ White 2014, p. xxiv-xxv.

- ^ a b White 1995, p. xlvii.

- ^ Ceresi & McMains.

- ^ Thorn, March 26, 2014

- ^ a b Thorn, May 26, 2014.

- ^ Whirty, May 4, 2014.

- ^ Thorn, May 12, 2014.

References

[edit]- "1911-12 Fe". Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database. Seamheads.com. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Calvin, Floyd J. (March 12, 1927). "Sol White Recalls Baseball's Greatest Days". Pittsburgh Courier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Ceresi, Frank; McMains, Carol. "Sol White's 1907 'History of Colored Base Ball'". National Pastime Museum. 33 Baseball Foundation. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- Hurd, Jay (October 7, 2011). "Sol White". SABR Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Lomax, Michael E. (2003). Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860-1901: Operating By Any Means Necessary. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2970-2.

- Riley, James A. (1994). "White, Solomon (Sol)". The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. Carroll & Graf. pp. 836–37. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- (Riley.) Sol White, Personal profiles at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. – identical to Riley (confirmed 2010-04-13)

- Thorn, John (May 12, 2014). "Baseball Remembers Sol White". Our Game. MLB.com. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- Thorn, John (May 26, 2014). "Sol White's Family, Lost and Found". Our Game. MLB.com. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- Walker, Weldy W. (March 14, 1888). "Why Discriminate? An Appeal to the Tri-State League By a Colored Player". The Sporting Life. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Walton, Lester A. (August 3, 1911). "Philadelphia Giants Disband". New York Age. New York City.

- Whirty, Ryan (May 4, 2014). "Respect for baseball legend Sol White". Staten Island Advance. Staten Island, New York. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- White, Sol (1995). Sol White's History of Colored Base Ball, with Other Documents of the Early Black Game, 1886-1936. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4771-0.

- White, Sol (2014). Sol White's Official Base Ball Guide. South Orange, New Jersey: Summer Games Books. ISBN 978-1-938545-21-4.

- Wilson, W. Rollo (January 16, 1926). "Eastern Snapshots". Pittsburgh Courier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

External links

[edit]- Negro league baseball statistics and player information from Seamheads.com, or Baseball Reference (Negro leagues)

- Sol White managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com and Seamheads

- Sol White at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Sol White at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum's eMuseum

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Negro league baseball managers

- Baseball developers

- Ansonia Cuban Giants players

- Brooklyn Royal Giants players

- Columbus Buckeyes (Negro leagues) players

- Cuban Giants players

- Cuban X-Giants players

- New York Lincoln Giants players

- New York Gorhams players

- Newark Stars players

- Page Fence Giants players

- Philadelphia Giants players

- Pittsburgh Keystones players

- 19th-century baseball players

- People from Bellaire, Ohio

- 1868 births

- 1955 deaths

- People from Central Islip, New York

- Sportspeople from Suffolk County, New York

- Journalists from Ohio

- Sportswriters from New York (state)

- 20th-century African-American people