Louis Santop

| Louis Santop | |

|---|---|

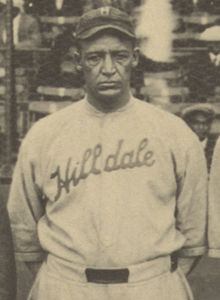

Santop in 1924 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: January 17, 1889 Tyler, Texas, U.S. | |

| Died: January 22, 1942 (aged 53) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| Negro leagues debut | |

| 1909, for the Philadelphia Giants | |

| Last appearance | |

| 1926, for the Hilldale Daisies | |

| Career statistics | |

| Batting average | .317 |

| Hits | 111 |

| Home runs | 7 |

| Runs batted in | 65 |

| Teams | |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 2006 |

| Election method | Committee on African-American Baseball |

Louis Santop Loftin (January 17, 1889 – January 22, 1942) was an American baseball catcher in the Negro leagues. He became "one of the earliest superstars" and "black baseball's first legitimate home-run slugger" (Riley), and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. Some sources show a birth year of 1890, but his Navy[3] records and Baseball Hall of Fame records support the earlier date.

Playing career

[edit]Santop was born in Tyler, Texas. At age 19 he played for teams in Fort Worth, Texas and Guthrie, Oklahoma before joining the Philadelphia Giants. In 1910, his only full season with Philadelphia, Santop and fellow rookie Dick Redding formed a "kid battery", catcher and pitcher. (Riley)

Most of the teams he played for were not considered major league teams (Hillsdale in 1923-26 is the exception), so his performance is not fully documented. Baseball Reference shows a career batting average of .356 in 433 games[4] but the Seamheads database shows .328 in 515 games.[5] His four years with the Hilldale Daisies are well documented: he hit .363 in 115 games, although he played sparingly in 1925-1926. In 15 games against White major league pitchers he hit .316.[6] With the New York Lincoln Giants and New York Lincoln Stars in 1911-1916, he was catching two players considered some of the hardest throwing pitchers in the league: Smokey Joe Williams and "Cannonball" Dick Redding.[7] While playing for the Lincoln Giants in 1913, he was credited with a 485-foot home run "the longest hit of the season."[8]

He was named as the catcher for the Negro Leagues East All-Star Team in 1917, 1918, 1921, 1922, and 1924.[9]

During his playing career, the 6 ft. 4 in. (1.93 m) 240-pound Santop was involved in some notable incidents. For example, Santop was the recipient of a knockdown pitch from ex-New York Giant Jeff Tesreau in an exhibition game. Santop yelled to Tesreau, who were both Tyler, Texas natives, "You wouldn't throw at a hometown boy, would you?" On another occasion, he broke three of Oscar Charleston's ribs in an altercation.[10]

While playing for the Hilldale Club in 1918, Santop was drafted in July in Class 1-A.[11] However, one month later, one newspaper reported that doctors at Camp Dix examined him and "found he had a broken and badly twisted arm." The report said he had an accident several years before and that "It made it impossible to handle a gun or salute properly." It went on to say he was discharged as physically unfit for service.[12] However, Santop served in the Navy as a mess attendant and fireman from October 21, 1918 to August 13, 1919.[3]

After the war, Santop was the league's biggest drawing card[13] and received $500 a month, one of the highest salaries paid, playing for the Hilldale Daisies.

Santop was a match for Josh Gibson. Gibson was often called "The Black Babe Ruth", but he wasn't the first to bear that title. It was applied earlier to Santop.[14] When Ruth and Santop faced each other in 1920, Ruth went 0–4, while Santop had 3 hits in 4 at-bats.[15]

Hilldale won pennants from 1923 to 1925, but an error in the 1924 Colored World Series basically ended Santop's Negro League career. With Hilldale leading a game 2–1 in the bottom of the ninth with one out and the winning runs on base, Santop dropped a popup off the bat of Monarchs catcher Frank Duncan that would have been the second out. On the next pitch, Duncan delivered the game-winning hit. In addition to the embarrassment, Santop was berated by his manager, Frank Warfield, in a public, profanity-filled tirade. The following year, Biz Mackey took over as starting catcher, and Santop was released by the team the next season.

After his playing career in the Negro leagues ended, he formed his own semi-pro team, the Santop Bronchos, which played from 1928[16] until at least 1932.[17]

Legacy

[edit]Santop was rated by Rollo Wilson, described as the Grantland Rice of black sports writers, as the first-string catcher on his all-time black baseball team. In 1952, he was included on the Pittsburgh Courier's All-Time All-Star Team.[18]

After retiring from baseball, Santop became a broadcaster for radio station WELK in Philadelphia and eventually a bartender in Philadelphia, before falling ill and eventually dying in a Philadelphia naval hospital in 1942, at age 52. He bequeathed his substantial baseball memorabilia collection to Bill Yancey, who contributed it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.[19]

Sources

[edit]- Holway, John (2001). The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues. Fern Park: Hastings House. ISBN 0-8038-2007-0.

- Lester, Larry (2006). Baseball's First Colored World Series. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-2617-9.

- Riley, James A. (1994). "Santop, Louis (Top, Big Bertha)". The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. Carroll & Graf. pp. 695–97. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- (Riley.) Louis Santop, Personal profiles at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. – identical to Riley (confirmed 2010-04-14)

- Holway, John (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers, Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

References

[edit]- ^ "Lincoln Giants Win First Two Games in Championship Series" Indianapolis Freeman, Indianapolis, Indiana, Saturday, August 2, 1913, Page 4, Columns 3 and 4

- ^ "With Taber on Mound Chester Beats Hilldale" Chester Times, Chester, PA, Tuesday, July 29, 1924, Page 6, Column 1

- ^ a b "AUSTIN (Texas)". Texas, World War I Records, 1917-1920.

- ^ "Baseball Reference Louis Santop". Baseball Reference. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ "Seamheads Louis Santop". Seamheads. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Holoway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. New York: Carroll & Graf. p. 95. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

- ^ Holway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. New York: Carroll & Graf. pp. 61–87. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

- ^ "Dominicans Lose to Armory Nine". Newark Evening Star. July 14, 1913. p. 15.

- ^ Holway, John B. (2001). The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues. Fern Park Florida: Hastings House. pp. 119–191. ISBN 0-8038-2007-0.

- ^ Holway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. New York: Carroll & Graf. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

- ^ "Santop, Webster and Tom Williams" Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Wednesday, July 17, 1918, Page 11, Column 3

- ^ "Noted Athletes at Dix are Rejected" The Sun, New York, New York, Sunday, August 11, 1918, Page 9, Column 1

- ^ Holway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. New York: Carroll & Graf. p. 91. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

- ^ "Stengel's Stars Play Hilldale". Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger. October 6, 1920. p. 20.

- ^ "Easy for Hillsdale". Philadelphia Inquirer. October 8, 1920. p. 18.

- ^ "Colored Team Causes Trouble". Lancaster New Era. September 17, 1928. pp. 14–15.

- ^ "Trenton Batsmen Open with Santops at Bradley Field". Asbury Park Evening Press. August 19, 1932. p. 13.

- ^ Holway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Carroll & Graf. p. 384.

- ^ Holway, John B. (1992). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. New York: Carroll & Graf. p. 94. ISBN 0-88184-764-X.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB, or Baseball Reference and Baseball-Reference Black Baseball stats and Seamheads

- Louis Santop at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- 1889 births

- 1942 deaths

- Sportspeople from Tyler, Texas

- Baseball players from Smith County, Texas

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen

- Baseball catchers

- Brooklyn Royal Giants players

- Hilldale Club players

- New York Lincoln Giants players

- New York Lincoln Stars players

- Oklahoma Monarchs players

- Philadelphia Giants players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- United States Army personnel of World War I