Peʻa

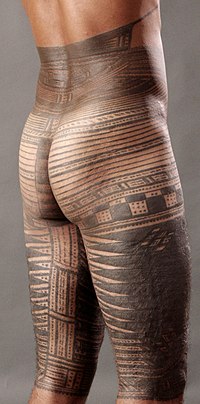

The Peʻa is the popular name of the traditional male tatau (tattoo) of Samoa, also known as the malofie.[1] It is a common mistake for people to refer to the pe'a as sogaimiti, because sogaimiti refers to the man with the pe'a and not the pe'a itself. It covers the body from the middle of the back to the knees, and consists of heavy black lines, arrows, and dots.[2]

History

[edit]The tattoo was originally made of bone or sharpened boar husk into a comb style with serrated teeth shaped like needles. It was then attached to a small patch of sea turtle which was connected to a wooden handle.

In the 1830s, English missionaries attempted to abolish the pe'a by banning it in missionary schools. The purpose of this was to "westernise" the Samoans, but during the time that tattooing was banned, it was still done in secret.[3] Because of this, Samoa is the only Polynesian country that has managed to retain its traditional tattoos in modern times, although it is done to a much lesser extent than it used to be.[4]

In present times, the traditional design of Pe'a continues to be a source of sacred cultural heritage, as an act of honour.

Description

[edit]The Pe'a covers the body from the middle of the back to the knees. The word tattoo in the English language is believed to have originated from the Samoan word "tatau".

The tatau process for the Pe'a is extremely painful,[5] and undertaken by tufuga ta tatau (master tattooists), using a set of handmade tools: pieces of bone, turtle shell and wood. The tufuga ta tatau are revered masters in Samoan society. In Samoan custom, a Pe'a is only done the traditional way, with aspects of cultural ceremony and ritual, and has a strong meaning for the one who receives it. The tufuga ta tatau works with two assistants, called 'au toso, who are often apprentice tattooists and they stretch the skin, wipe the excess ink and blood and generally support the tattooist in their work. The process takes place with the subject lying on mats on the floor with the tattooist and assistants beside them. Family members of the person getting the tattoo are often in attendance at a respectful distance to provide words of encouragement, sometimes through song. The Pe'a can take less than a week to complete, or, in some cases, years.

The ink colour is black. The tattoo starts on the back and finishes on the navel. Overall, the design is symmetrical with a pattern consisting mainly of straight lines and larger blocks of dark cover, usually around the thighs. Some art experts have made a comparison between the distinctive Samoan tattoo patterns to other artforms including designs on tapa cloth and Lapita pottery.[6]

Traditional Samoan tattooing of the Pe'a, body tattoo, is an ordeal that is not lightly undergone. It can take many weeks to complete, is very painful and used to be a necessary prerequisite to receiving a Fa'amatai title; this however is no longer the case. Tattooing was also a very costly procedure, the tattooer receiving in the region of 700 fine mats as payment. It was not uncommon for half a dozen boys to be tattooed at the same time, requiring the services of four or more tattooers. It was not just the men who received tattoos, but the women too, although their designs are of a much lighter nature, resembling a filigree rather than having the large areas of solid dye which are frequently seen in men's tattoos. Nor was the tattooing of women as ritualised as that of the men.[7]

Lama

[edit]Better known by its Hawaiʻian name, kukui, the oily kernel of the husked candlenut, known in Samoan as tuitui or lama, is burned and the black soot collected is used as the color base for the traditional ink used in Samoan tattooing. The modern tufuga artists utilize commercially produced inks that comply with international tattoo regulations and local health safety codes.[8][9]

Societal significance

[edit]Samoan males with a Pe'a are called Soga'imiti and are respected for their courage. Untattooed Samoan males are colloquially referred to as telefua or telenoa, literally "naked". Those who begin the tattooing ordeal but do not complete it due to the pain, or more rarely the inability to adequately pay the tattooist, are called Pe'a mutu, a mark of shame.[10] The traditional female tattoo in Samoa is the Malu. In Samoan society, the Pe'a and the Malu are viewed with cultural pride and identity as well as a hallmark of manhood and womanhood.

'Tatau is an ancient Polynesian art form which is associated with the rites of passage for men. Pe'a is also the Samoan word for the flying fox (fruit bat, Pteropus samoensis), and there are many Polynesian myths, proverbs and legends associated with this winged creature.[11] One legend from the island of Savai'i is about Nafanua, Samoa's goddess of war, rescued by flying foxes when she was stranded on an inhospitable island.[12]

Origins

[edit]In Polynesia, the origins of tattoo is varied. Samoa credit Fiji as the source of the tatau, the Fijians credit the act of Veiqia the tattooing of Fijian women only, and the Māori of New Zealand credit the underworld.[13]

In Samoan mythology, the origin of the tatau in Samoa is told in a myth about twin sisters Tilafaiga and Taema who swam from Fiji (as in Fitiuta, Manu'a) to Samoa with a basket of tattoo tools. As they swam they sang a song which said only women get tattooed. But as they neared the village of Falealupo on the island of Savai'i, they saw a clam underwater and dived down to get it. When they emerged, their song had changed, the lyrics now saying that only men get the tattoo and not women. This song is known in Samoa as the Pese o le Pe'a or Pese o le Tatau.[14]

The word tatau has many meanings in Samoa. Tā means to strike, and in the case of tattooing, the tap tap sound of the tattooist's wooden tools. Tau means to reach an end, a conclusion, as well as war or battle. Tatau also means rightness or balance. It also means to wring moisture from something, like wet cloth, or in the case of the pe'a process, the ink from the skin. Tata means to strike repeatedly or perform a rhythm. For example, tātā le ukulele means 'play the ukulele.'

Implements

[edit]The tools of the tufuga ta tatau comprise a set of serrated bone combs (au), which were lashed to small tortoise shell fragments which were in turn lashed to a short wooden handle; a tapping mallet (sausau) for driving the combs into the skin; coconut shell cups (ipuniu) to mix and store the tattooing ink ("lama") made from burnt candlenut soot; and lengths of tapa cloth ("solo") used to wipe blood and clean tools.[15] The tools are traditionally stored in a cylindrical wooden container called "tunuma" which are lined with tapa cloth and designed to hold the 'au vertically with the delicate combs facing the center of the cylinder to prevent damage. The "sausau" mallet was shaped from a length of hardwood approximately as long as the forearm and about the diameter of the thumb. Various sizes of "au" combs were painstakingly fashioned by filing sections of boar tusk with tiny abrasive files knapped from volcanic flint, chert, and/or basalt rock.[16] The smallest combs, used to make dots ("tala"), are aptly called 'au fa'atala, or 'au mono. Single lines of varying widths were tapped with various sizes of 'au sogi, while the solid blocks of tattooing were accomplished with the 'au tapulu.

Tattooing Guild

[edit]The prestigious role of master tattooist (tufuga ta tatau) has been maintained through hereditary titles within two Samoan clans, the Sa Su'a (matai) family from Savai'i and the Sa Tulou'ena matai family of Upolu.[17] In ancient times the masters were elevated to high social status, wealth, and legendary prestige due to their crucial roles in Samoan society. It is known that Samoan tufuga also performed tattooing for Tongan and Fijia paramount chiefly families. The late Sua Sulu'ape Paulo II was a well-known master whose life and work features in the photography of New Zealander Mark Adams. His brother Su'a Sulu'ape Petelo, who lives and carries out Samoan tattooing at Faleasi'u village in Upolu, is one of the most respected master tattooists today. Masters from these ʻaiga (families), were designated in their youth and underwent extensive apprenticeships in the role of solo and tattooist assistants for many years, under their elder tufuga.

The traditional art of tattoo in Samoa was suppressed with the arrival of English missionaries and Christianity in the 1830s.[18] However, it was perpetuated throughout the colonial era and was continually practiced in its intact form into the modern age.[19] This was not the case, however, in the other Polynesian islands, and the master tattooists of the Su'a Sulu'ape family have been instrumental in the revival of traditional tattooing in French Polynesia, Tonga, New Zealand, the Cook Islands, and Hawaii, where a new generation of Pacific tattooists have learned the Samoan techniques and protocols.

In popular culture

[edit]- An early documentation of the pe'a on film is seen in Moana (1926), directed by American Robert J. Flaherty and filmed in Safune on the island of Savai'i. The film shows the young hero Moana's friend receiving a pe'a.

- The pe'a is featured in the 2007 horror film The Tattooist.

- The Disney animated film Moana (2016) shows a young man receiving his first pe'a.

- In professional wrestling, many Samoan wrestlers prominently have pe'a tattoos such as Roman Reigns, The Rock, Solo Sikoa, and the Usos.

Non-Samoans and the Pe'a

[edit]It is extremely rare for non-Samoans to receive the pe'a or the malu. Tongan nobility of the Tu'i Kanokupolu dynasty established the practice of pe'a tattooing among Tongan aristocracy in the pre-contact era. There are stories of Tongan royalty, Tu'i Tonga Fatafehi Fakauakimanuka and King George Tupou I of the ritual under Samoan tufuga ta tatau. European beachcombers and runaway sailors were the first non-Polynesians to receive the pe'a during the early 1800s; among the earliest non-Polynesians to receive the pe'a was an American named Mickey Knight, as well as a handful of Europeans and Americans who had jumped ship, were abandoned, or visited Samoa.[20] During the colonial era when Samoa fell under German rule, several Europeans underwent the pe'a ritual, including Englishman Arthur Pink, Erich Schultz-Ewerth (the last German governor of Samoa), and a number of German colonial officials.[21][22][20] In more recent times, many afakasi (half Samoans) and other non-Samoan men have become soga'imiti, including Noel Messer, FuneFe'ai Carl Cooke, Rene Persoons and artist Tony Fomison, (1939–1990), one of New Zealand's foremost painters, who received a pe'a in 1979. It is also known that several women, such as Karina Persoons, received a malu from tufuga Su'a Sulu'ape Petelo.[23]

Lyrics Pese o le Tatau song

[edit]It is known that the last verse was written in modern times, as it does not match the orthography of the first verses. Oral tradition maintains that this song is derived from a pre-colonial chant.

|

O le mafuaaga lenei ua iloa O le taaga o le tatau i Samoa O le malaga a teine to'alua Na feausi mai Fiti le vasa loloa Na la aumai ai o le atoau ma sia la pese e tutumau Fai mai e tata o fafine Ae le tata o tane A o le ala ua tata ai tane Ina ua sese sia la pese Taunuu i gatai o Falealupo Ua vaaia loa o se faisua ua tele Totofu loa lava o fafine Ma ua sui ai sia la pese Fai mai e tata o tane Ae le tata o fafine Talofa i si tama ua taatia O le tufuga lea ua amatalia Talofa ua tagi aueue Ua oti'otisolo le au tapulutele Sole Sole, ai loto tele O le taaloga a tama tane E ui lava ina tiga tele Ae mulimuli ana ua a fefete O atu motu uma o le Pasefika Ua sili Samoa le ta'taua O le soga'imiti ua savalivali mai Ua fepulafi mai ana faaila Aso faaifo, faamulialiao Faaatualoa, selu faalaufao O le sigano faapea faaulutao Ua ova i le vasalaolao

|

This is the known origin Of the tattooing of the tatau in Samoa A journey by two maidens Who swam from Fiji across the open sea They brought the tattooing kit And recited their unchanging chant That said women were to be tattooed But men were not to be tattooed Thus the reason why men are now tattooed Is because of the confusion of the maidens' chant Arriving at the coast of Falealupo They spotted a giant clam As the maidens dived Their chant was reversed To say that men were to be tattooed And not women Pity the youth now lying While the tufuga starts Alas he is crying loudly As the tattooing tool cuts all over Young fellow, young fellow, be brave This is the sport of male heirs Despite the enormous pain Afterwards you will swell with pride Of all the countries in the Pacific Samoa is the most famous The sogaimiti walking towards you With his fa'aila glistening Curved lines, motifs like ali Like centipedes, combs like wild bananas Like sigano and spearheads The greatest in the whole world! |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Samoan tatau (tattooing) - Collections Online - Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". Collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ ""I did this to honour my Mum's pain."". Whanganui Chronicle. 16 May 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33695-4.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33695-4.

- ^ "Pe'a tattooing – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2012-09-21. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ Mick Prendergrast, Roger Neich (2004). Pacific Tapa. University of Hawaii Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8248-2929-8. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Tattoos". Samoa. Archived from the original on 2012-12-14. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ "Call for safe tattooing practices in the Samoan community". RNZ. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing". New Zealand Geographic. 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

Kerosene soot or Indian ink was substituted for the traditional burned candlenut-soot pigment, turtle shell was replaced by Perspex and other plastics, and sennit by nylon fishing line. In the interests of hygiene, tufuga began to use steel needles that could be sterilised in place of bone, and took to wearing latex gloves and covering pillows with plastic.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of body adornment, Part 46. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9.

- ^ Vilsoni Hereniko, Rob Wilson (1999). Inside out: literature, cultural politics, and identity in the new Pacific. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-8476-9143-2.

- ^ Geiger, Jeffrey (30 April 2007). Facing the Pacific: Polynesia and the U.S. imperial imagination. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8248-3066-3.

- ^ Ellis, Juniper (2008). Tattooing the world: Pacific designs in print & skin. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-231-14369-1.

- ^ Philip Culbertson; Margaret Nelson Agee; Cabrini 'Ofa Makasiale (30 September 2007). Penina uliuli:Contemporary challenges in mental health for Pacific peoples. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8248-3224-7.

- ^ "Traditional Samoan tattoos - TattoozZa". tattoozza.com. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ^ Hīroa, Te Rangi. Samoan Material Culture. p. 637.

- ^ "NZEPC - Albert Wendt - Tatauing the Post - Colonial Body". Nzepc.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of body adornment. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-313-33695-9.

- ^ Ellis, Juniper (2008). Tattooing the world:Pacific Designs in Print and Skin. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-231-14369-1.

- ^ a b Mallon, Sean. Samoan Art and Artists. p. 111.

- ^ Arnold Safroni-Middleton (1915). Sailor and Beachcomber.

- ^ Retzlaff, Misa Telefoni. An Enduring Legacy - The German Influence in Samoan Culture and History.

- ^ Skrine, Amy. "Mark Adams' Pe'a Exhibition and Tattoo". Graduate Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies. 4 (2): 95–98.

Bibliography

[edit]- McLean, M; D'Souza, A (Feb 2011). "Life-threatening cellulitis after traditional Samoan tattooing". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 35 (1): 27–9. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00658.x. PMID 21299697. S2CID 36922051.

External links

[edit]- Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body paper by Albert Wendt, Originally published in Span 42-43 (April–October 1996): 15-29

- Tatau song with guitar during female malu tattoo session, Youtube