Singular point of a curve

In geometry, a singular point on a curve is one where the curve is not given by a smooth embedding of a parameter. The precise definition of a singular point depends on the type of curve being studied.

Algebraic curves in the plane

[edit]Algebraic curves in the plane may be defined as the set of points (x, y) satisfying an equation of the form where f is a polynomial function If f is expanded as If the origin (0, 0) is on the curve then a0 = 0. If b1 ≠ 0 then the implicit function theorem guarantees there is a smooth function h so that the curve has the form y = h(x) near the origin. Similarly, if b0 ≠ 0 then there is a smooth function k so that the curve has the form x = k(y) near the origin. In either case, there is a smooth map from to the plane which defines the curve in the neighborhood of the origin. Note that at the origin so the curve is non-singular or regular at the origin if at least one of the partial derivatives of f is non-zero. The singular points are those points on the curve where both partial derivatives vanish,

Regular points

[edit]Assume the curve passes through the origin and write Then f can be written If is not 0 then f = 0 has a solution of multiplicity 1 at x = 0 and the origin is a point of single contact with line If then f = 0 has a solution of multiplicity 2 or higher and the line or is tangent to the curve. In this case, if is not 0 then the curve has a point of double contact with If the coefficient of x2, is 0 but the coefficient of x3 is not then the origin is a point of inflection of the curve. If the coefficients of x2 and x3 are both 0 then the origin is called point of undulation of the curve. This analysis can be applied to any point on the curve by translating the coordinate axes so that the origin is at the given point.[1]

Double points

[edit]

If b0 and b1 are both 0 in the above expansion, but at least one of c0, c1, c2 is not 0 then the origin is called a double point of the curve. Again putting f can be written Double points can be classified according to the solutions of

Crunodes

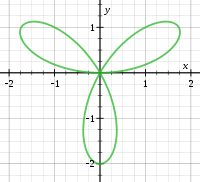

[edit]If has two real solutions for m, that is if then the origin is called a crunode. The curve in this case crosses itself at the origin and has two distinct tangents corresponding to the two solutions of The function f has a saddle point at the origin in this case.

Acnodes

[edit]If has no real solutions for m, that is if then the origin is called an acnode. In the real plane the origin is an isolated point on the curve; however when considered as a complex curve the origin is not isolated and has two imaginary tangents corresponding to the two complex solutions of The function f has a local extremum at the origin in this case.

Cusps

[edit]If has a single solution of multiplicity 2 for m, that is if then the origin is called a cusp. The curve in this case changes direction at the origin creating a sharp point. The curve has a single tangent at the origin which may be considered as two coincident tangents.

Further classification

[edit]The term node is used to indicate either a crunode or an acnode, in other words a double point which is not a cusp. The number of nodes and the number of cusps on a curve are two of the invariants used in the Plücker formulas.

If one of the solutions of is also a solution of then the corresponding branch of the curve has a point of inflection at the origin. In this case the origin is called a flecnode. If both tangents have this property, so is a factor of then the origin is called a biflecnode.[2]

Multiple points

[edit]

In general, if all the terms of degree less than k are 0, and at least one term of degree k is not 0 in f, then curve is said to have a multiple point of order k or a k-ple point. The curve will have, in general, k tangents at the origin though some of these tangents may be imaginary.[3]

Parametric curves

[edit]A parameterized curve in is defined as the image of a function The singular points are those points where

Many curves can be defined in either fashion, but the two definitions may not agree. For example, the cusp can be defined on an algebraic curve, or on a parametrised curve, Both definitions give a singular point at the origin. However, a node such as that of at the origin is a singularity of the curve considered as an algebraic curve, but if we parameterize it as then never vanishes, and hence the node is not a singularity of the parameterized curve as defined above.

Care needs to be taken when choosing a parameterization. For instance the straight line y = 0 can be parameterised by which has a singularity at the origin. When parametrised by it is nonsingular. Hence, it is technically more correct to discuss singular points of a smooth mapping here rather than a singular point of a curve.

The above definitions can be extended to cover implicit curves which are defined as the zero set of a smooth function, and it is not necessary just to consider algebraic varieties. The definitions can be extended to cover curves in higher dimensions.

A theorem of Hassler Whitney[4][5] states

Theorem — Any closed set in occurs as the solution set of for some smooth function

Any parameterized curve can also be defined as an implicit curve, and the classification of singular points of curves can be studied as a classification of singular points of an algebraic variety.

Types of singular points

[edit]Some of the possible singularities are:

- An isolated point: an acnode

- Two lines crossing: a crunode

- A cusp: also called a spinode

- A tacnode:

- A rhamphoid cusp:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hilton Chapter II §1

- ^ Hilton Chapter II §2

- ^ Hilton Chapter II §3

- ^ Th. Bröcker, Differentiable Germs and Catastrophes, London Mathematical Society. Lecture Notes 17. Cambridge, (1975)

- ^ Bruce and Giblin, Curves and singularities, (1984, 1992) ISBN 0-521-41985-9, ISBN 0-521-42999-4 (paperback)

- Hilton, Harold (1920). "Chapter II: Singular Points". Plane Algebraic Curves. Oxford.