Sexism

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but primarily affects women and girls.[1] It has been linked to gender roles and stereotypes,[2][3] and may include the belief that one sex or gender is intrinsically superior to another.[4] Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.[5][6] Discrimination in this context is defined as discrimination toward people based on their gender identity[7] or their gender or sex differences.[8] An example of this is workplace inequality.[8] Sexism refers to violation of equal opportunities (formal equality) based on gender or refers to violation of equality of outcomes based on gender, also called substantive equality.[9] Sexism may arise from social or cultural customs and norms.[10]

Etymology and definitions

According to legal scholar Fred R. Shapiro, the term "sexism" was most likely coined on November 18, 1965, by Pauline M. Leet during a "Student-Faculty Forum" at Franklin and Marshall College. Specifically, the word sexism appears in Leet's forum contribution "Women and the Undergraduate", and she defines it by comparing it to racism, stating in part, "When you argue ... that since fewer women write good poetry this justifies their total exclusion, you are taking a position analogous to that of the racist—I might call you, in this case, a 'sexist' ... Both the racist and the sexist are acting as if all that has happened had never happened, and both of them are making decisions and coming to conclusions about someone's value by referring to factors which are in both cases irrelevant."[11]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first time the term sexism appeared in print was in Caroline Bird’s speech "On Being Born Female", which was delivered before the Episcopal Church Executive Council in Greenwich, Connecticut, and subsequently published on November 15, 1968, in Vital Speeches of the Day (p. 6).[12]

Sexism may be defined as an ideology based on the belief that one sex is superior to another.[4][13][14] It is discrimination, prejudice, or stereotyping based on gender, and is most often expressed toward women and girls.[1]

Sociology has examined sexism as manifesting at both the individual and the institutional level.[14] According to Richard Schaefer, sexism is perpetuated by all major social institutions.[14] Sociologists describe parallels among other ideological systems of oppression such as racism, which also operates at both the individual and institutional level.[15] Early female sociologists Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Ida B. Wells, and Harriet Martineau described systems of gender inequality, but did not use the term sexism, which was coined later. Sociologists who adopted the functionalist paradigm, e.g. Talcott Parsons, understood gender inequality as the natural outcome of a dimorphic model of gender.[16]

Psychologists Mary Crawford and Rhoda Unger define sexism as prejudice held by individuals that encompasses "negative attitudes and values about women as a group."[17] Peter Glick and Susan Fiske coined the term ambivalent sexism to describe how stereotypes about women can be both positive and negative, and that individuals compartmentalize the stereotypes they hold into hostile sexism or benevolent sexism.[18]

Feminist author bell hooks defines sexism as a system of oppression that results in disadvantages for women.[19] Feminist philosopher Marilyn Frye defines sexism as an "attitudinal-conceptual-cognitive-orientational complex" of male supremacy, male chauvinism, and misogyny.[20]

Philosopher Kate Manne defines sexism as one branch of a patriarchal order. In her definition, sexism rationalizes and justifies patriarchal norms, in contrast with misogyny, the branch which polices and enforces patriarchal norms. Manne says that sexism often attempts to make patriarchal social arrangements seem natural, good, or inevitable so that there appears to be no reason to resist them.[21]

History

Pre-agricultural world

Evidence is lacking to support the idea that many pre-agricultural societies afforded women a higher status than women today,[22] however, historians are reasonably sure that women had roughly equal social power to men in many such societies.[23]

Ancient civilizations

After the adoption of agriculture and sedentary cultures, the concept that one gender was inferior to the other was established; most often this was imposed upon women and girls.[24]

The status of women in ancient Egypt depended on their fathers or husbands, but they had property rights and could attend court, including as plaintiffs.[25] Examples of unequal treatment of women in the ancient world include written laws preventing women from participating in the political process; for instance, women in ancient Rome could not vote or hold political office.[26] Another example is scholarly texts that indoctrinate children in female inferiority; women in ancient China were taught the Confucian principles that a woman should obey her father in childhood, husband in marriage, and son in widowhood.[27] On the other hand, women of the Anglo-Saxon era were commonly afforded equal status.[28]

Witch hunts and trials

Sexism may have been the impetus that fueled the witch trials between the 15th and 18th centuries.[30] In early modern Europe, and in the European colonies in North America, claims were made that witches were a threat to Christendom. The misogyny of that period played a role in the persecution of these women.[31][32]

In Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer, the book which played a major role in the witch hunts and trials, the author argues that women are more likely to practice witchcraft than men, and writes that:

- All wickedness is but little to the wickedness of a woman ... What else is a woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colors![33]

Witchcraft remains illegal in several countries, including Saudi Arabia, where it is punishable by death. In 2011, a woman was beheaded in that country for "witchcraft and sorcery".[34] Murders of women after being accused of witchcraft remain common in some parts of the world; for example, in Tanzania, about 500 elderly women are murdered each year following such accusations.[35]

When women are targeted with accusations of witchcraft and subsequent violence, it is often the case that several forms of discrimination interact – for example, discrimination based on gender with discrimination based on caste, as is the case in India and Nepal, where such crimes are relatively common.[36][37]

Coverture and other marriage regulations

Until the 20th century, U.S. and English law observed the system of coverture, where "by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage".[39] U.S. women were not legally defined as "persons" until 1875 (Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162).[40] A similar legal doctrine, called marital power, existed under Roman Dutch law (and is still partially in force in present-day Eswatini).[citation needed]

Restrictions on married women's rights were common in Western countries until a few decades ago: for instance, French married women obtained the right to work without their husband's permission in 1965,[41][42][43] and in West Germany women obtained this right in 1977.[44][45] During the Franco era, in Spain, a married woman required her husband's consent (called permiso marital) for employment, ownership of property and traveling away from home; the permiso marital was abolished in 1975.[46] In Australia, until 1983, a married woman's passport application had to be authorized by her husband.[47]

Women in parts of the world continue to lose their legal rights in marriage. For example, Yemeni marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[48] In Iraq, the law allows husbands to legally "punish" their wives.[49] In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Family Code states that the husband is the head of the household; the wife owes her obedience to her husband; a wife has to live with her husband wherever he chooses to live; and wives must have their husbands' authorization to bring a case in court or initiate other legal proceedings.[50]

Abuses and discriminatory practices against women in marriage are often rooted in financial payments such as dowry, bride price, and dower.[51] These transactions often serve as legitimizing coercive control of the wife by her husband and in giving him authority over her; for instance Article 13 of the Code of Personal Status (Tunisia) states that, "The husband shall not, in default of payment of the dower, force the woman to consummate the marriage",[52][53] implying that, if the dower is paid, marital rape is permitted. In this regard, critics have questioned the alleged gains of women in Tunisia, and its image as a progressive country in the region, arguing that discrimination against women remains very strong there.[54][55][56]

The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) has recognized the "independence and ability to leave an abusive husband" as crucial in stopping mistreatment of women.[57] However, in some parts of the world, once married, women have very little chance of leaving a violent husband: obtaining a divorce is very difficult in many jurisdictions because of the need to prove fault in court. While attempting a de facto separation (moving away from the marital home) is also impossible because of laws preventing this. For instance, in Afghanistan, a wife who leaves her marital home risks being imprisoned for "running away".[58][59] In addition, many former British colonies, including India, maintain the concept of restitution of conjugal rights,[60] under which a wife may be ordered by court to return to her husband; if she fails to do so, she may be held in contempt of court.[61][62] Other problems have to do with the payment of the bride price: if the wife wants to leave, her husband may demand the return of the bride price that he had paid to the woman's family; and the woman's family often cannot or does not want to pay it back.[63][64][65]

Laws, regulations, and traditions related to marriage continue to discriminate against women in many parts of the world, and to contribute to the mistreatment of women, in particular in areas related to sexual violence and to self-determination regarding sexuality, the violation of the latter now being acknowledged as a violation of women's rights. In 2012, Navi Pillay, then High Commissioner for Human Rights, stated that:

Women are frequently treated as property, they are sold into marriage, into trafficking, into sexual slavery. Violence against women frequently takes the form of sexual violence. Victims of such violence are often accused of promiscuity and held responsible for their fate, while infertile women are rejected by husbands, families and communities. In many countries, married women may not refuse to have sexual relations with their husbands, and often have no say in whether they use contraception ... Ensuring that women have full autonomy over their bodies is the first crucial step towards achieving substantive equality between women and men. Personal issues—such as when, how and with whom they choose to have sex, and when, how and with whom they choose to have children—are at the heart of living a life in dignity.[66]

Suffrage and politics

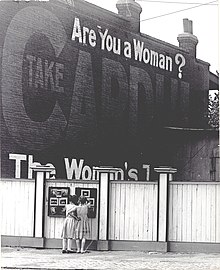

Gender has been used as a tool for discrimination against women in the political sphere. Women's suffrage was not achieved until 1893, when New Zealand was the first country to grant women the right to vote. Saudi Arabia is the most recent country, as of August 2015, to extend the right to vote to women in 2011.[67] Some Western countries allowed women the right to vote only relatively recently. Swiss women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971,[68] and Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last canton to grant women the right to vote on local issues in 1991, when it was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[69] French women were granted the right to vote in 1944.[70][71] In Greece, women obtained the right to vote in 1952.[72] In Liechtenstein, women obtained the right to vote in 1984, through the women's suffrage referendum of 1984.[73][74]

While almost every woman today has the right to vote, there is still progress to be made for women in politics. Studies have shown that in several democracies including Australia, Canada, and the United States, women are still represented using gender stereotypes in the press.[75] Multiple authors have shown that gender differences in the media are less evident today than they used to be in the 1980s, but are still present. Certain issues (e.g., education) are likely to be linked with female candidates, while other issues (e.g., taxes) are likely to be linked with male candidates.[75] In addition, there is more emphasis on female candidates' personal qualities, such as their appearance and their personality, as females are portrayed as emotional and dependent.[75]

There is a widespread imbalance of lawmaking power between men and women. The ratio of women to men in legislatures is used as a measure of gender equality in the United Nations' Gender Empowerment Measure and its newer incarnation the Gender Inequality Index. Speaking about China, Lanyan Chen stated that, since men more than women serve as the gatekeepers of policy making, this may lead to women's needs not being properly represented. In this sense, the inequality in lawmaking power also causes gender discrimination.[76]

Menus

Until the early 1980s, some high-end restaurants had two menus: a regular menu with the prices listed for men and a second menu for women, which did not have the prices listed (it was called the "ladies' menu"), so that the female diner would not know the prices of the items.[77] In 1980, Kathleen Bick took a male business partner out to dinner at L'Orangerie in West Hollywood. After she was given a women's menu without prices and her guest got one with prices, Bick hired lawyer Gloria Allred to file a discrimination lawsuit, on the grounds that the women's menu went against the California Civil Rights Act.[77] Bick stated that getting a women's menu without prices left her feeling "humiliated and incensed". The owners of the restaurant defended the practice, saying it was done as a courtesy, like the way men would stand up when a woman enters the room. Even though the lawsuit was dropped, the restaurant ended its gender-based menu policy.[77]

Trends over time

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2021) |

A 2021 study found little evidence that levels of sexism had changed from 2004 to 2018 in the United States.[78]

Gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are widely held beliefs about the characteristics and behavior of women and men.[79] Empirical studies have found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women in a number of activities.[80][81] Dustin B. Thoman and others (2008) hypothesize that "[t]he socio-cultural salience of ability versus other components of the gender-math stereotype may impact women pursuing math". Through the experiment comparing the math outcomes of women under two various gender-math stereotype components, which are the ability of math and the effort on math respectively, Thoman and others found that women's math performance is more likely to be affected by the negative ability stereotype, which is influenced by sociocultural beliefs in the United States, rather than the effort component. As a result of this experiment and the sociocultural beliefs in the United States, Thoman and others concluded that individuals' academic outcomes can be affected by the gender-math stereotype component that is influenced by the sociocultural beliefs.[82]

In language

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Sexism in language exists when language devalues members of a certain gender.[83] Sexist language, in many instances, promotes male superiority.[84] Sexism in language affects consciousness, perceptions of reality, encoding and transmitting cultural meanings and socialization.[83] Researchers have pointed to the semantic rule in operation in language of the male-as-norm. This results in sexism as the male becomes the standard and those who are not male are relegated to the inferior.[85] Sexism in language is considered a form of indirect sexism because it is not always overt.[86]

Examples include:

- Using generic masculine terms to reference a group of mixed gender, such as "mankind", "man" (referring to humanity), "guys", or "officers and men"

- Using the singular masculine pronoun (he, his, him) as the default to refer to a person of unknown gender

- Terms ending in "-man" that may be performed by those of non-male genders, such as businessman, chairman, or policeman

- Using unnecessary gender markers, such as "male nurse" implying that simply a "nurse" is by default assumed to be female.[87]

Sexist and gender-neutral language

Various 20th century feminist movements, from liberal feminism and radical feminism to standpoint feminism, postmodern feminism and queer theory, have considered language in their theorizing.[88] Most of these theories have maintained a critical stance on language that calls for a change in the way speakers use their language.

One of the most common calls is for gender-neutral language. Many have called attention, however, to the fact that the English language is not inherently sexist in its linguistic system, but the way it is used becomes sexist and gender-neutral language could thus be employed.[89]

Sexism in languages other than English

Romanic languages such as French[90] and Spanish[91] may be seen as reinforcing sexism, in that the masculine form is the default. The word "mademoiselle", meaning "miss", was declared banished from French administrative forms in 2012 by Prime Minister François Fillon.[90] Current pressure calls for the use of the masculine plural pronoun as the default in a mixed-sex group to change.[92] As for Spanish, Mexico's Ministry of the Interior published a guide on how to reduce the use of sexist language.[91]

German speakers have also raised questions about how sexism intersects with grammar.[93] The German language is heavily inflected for gender, number, and case; nearly all nouns denoting the occupations or statuses of human beings are gender-differentiated. For more gender-neutral constructions, gerund nouns are sometimes used instead, as this eliminates the grammatical gender distinction in the plural, and significantly reduces it in the singular. For example, instead of die Studenten ("the men students") or die Studentinnen ("the women students"), one writes die Studierenden ("the [people who are] studying").[94] However, this approach introduces an element of ambiguity, because gerund nouns more precisely denote one currently engaged in the activity, rather than one who routinely engages in it as their primary occupation.[95]

In Chinese, some writers have pointed to sexism inherent in the structure of written characters. For example, the character for man is linked to those for positive qualities like courage and effect while the character for wife is composed of a female part and a broom, considered of low worth.[96]

Gender-specific pejorative terms

Gender-specific pejorative terms intimidate or harm another person because of their gender. Sexism can be expressed in language with negative gender-oriented implications,[97] such as condescension. For example, one may refer to a female as a "girl" rather than a "woman", implying that she is subordinate or not fully mature. Other examples include obscene language. Some words are offensive to transgender people, including "tranny", "she-male", or "he-she". Intentional misgendering (assigning the wrong gender to someone) and the pronoun "it" are also considered pejorative.[98][99]

Occupational sexism

The practice of using first names for individuals from a profession that is predominantly female occurs in health care. Physicians are typically referred to using their last name, but nurses are referred to, even by physicians they do not know, by their first name. According to Suzanne Gordon, a typical conversation between a physician and a nurse is: "Hello Jane. I'm Dr. Smith. Would you hand me the patient's chart?"

–Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care[100]

Occupational sexism refers to discriminatory practices, statements or actions, based on a person's sex, occurring in the workplace. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination. In 2008, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have 20% less chance to have a job and are paid 17% less than men.[101] The report stated:

[In] many countries, labour market discrimination—i.e. the unequal treatment of equally productive individuals only because they belong to a specific group—is still a crucial factor inflating disparities in employment and the quality of job opportunities [...] Evidence presented in this edition of the Employment Outlook suggests that about 8 percent of the variation in gender employment gaps and 30 percent of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labor market.[101][102]

It also found that although almost all OECD countries, including the U.S.,[103] have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce.[101]

Women who enter predominantly male work groups can experience the negative consequences of tokenism: performance pressures, social isolation, and role encapsulation.[104] Tokenism could be used to camouflage sexism, to preserve male workers' advantage in the workplace.[104] No link exists between the proportion of women working in an organization/company and the improvement of their working conditions. Ignoring sexist issues may exacerbate women's occupational problems.[105]

In the World Values Survey of 2005, responders were asked if they thought wage work should be restricted to men only. In Iceland, the percentage that agreed was 3.6%, whereas in Egypt it was 94.9%.[106]

Gap in hiring

Research has repeatedly shown that mothers in the United States are less likely to be hired than equally qualified fathers and if hired, receive a lower salary than male applicants with children.[107][108][109][110]

One study found that female applicants were favored; however, its results have been met with skepticism from other researchers, since it contradicts most other studies on the issue. Joan C. Williams, a distinguished professor at the University of California's Hastings College of Law, raised issues with its methodology, pointing out that the fictional female candidates it used were unusually well-qualified. Studies using more moderately qualified graduate students have found that male students are much more likely to be hired, offered better salaries, and offered mentorship.[111][112]

In Europe, studies based on field experiments in the labor market, provide evidence for no severe levels of discrimination based on female gender. However, unequal treatment is still measured in particular situations, for instance, when candidates apply for positions at a higher functional level in Belgium,[113] when they apply at their fertile ages in France,[114] and when they apply for male-dominated occupations in Austria.[115]

Earnings gap

Studies have concluded that on average women earn lower wages than men worldwide. Some people argue that this results from widespread gender discrimination in the workplace. Others argue that the wage gap results from different choices by men and women, such as women placing more value than men on having children, and men being more likely than women to choose careers in high paying fields such as business, engineering, and technology.

Eurostat found a persistent, average gender pay gap of 27.5% in the 27 EU member states in 2008.[116] Similarly, the OECD found that female full-time employees earned 27% less than their male counterparts in OECD countries in 2009.[101][102]

In the United States, the female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2009; female full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers earned 77% as much as male FTYR workers. Women's earnings relative to men's fell from 1960 to 1980 (56.7–54.2%), rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (54.2–67.6%), leveled off from 1990 to 2000 (67.6–71.2%) and rose from 2000 to 2009 (71.2–77.0%).[117][118] As of the late 2010s, it has decreased back to around 1990 to 2000 levels (68.6-71.1%).[119][120] When the first Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963, female full-time workers earned 48.9% as much as male full-time workers.[117]

Research conducted in Czechia and Slovakia shows that, even after the governments passed anti-discrimination legislation, two thirds of the gender gap in wages remained unexplained and segregation continued to "represent a major source of the gap".[121]

The gender gap can also vary across-occupation and within occupation. In Taiwan, for example, studies show how the bulk of gender wage discrepancies occur within-occupation.[122] In Russia, research shows that the gender wage gap is distributed unevenly across income levels, and that it mainly occurs at the lower end of income distribution.[123] The research also found that "wage arrears and payment in-kind attenuated wage discrimination, particularly amongst the lowest paid workers, suggesting that Russian enterprise managers assigned lowest importance to equity considerations when allocating these forms of payment".[123]

The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between men and women (such as education, hours worked and occupation), innate behavioral and biological differences between men and women and discrimination in the labor market (such as gender stereotypes and customer and employer bias). Women take significantly more time off to raise children than men.[124] In certain countries such as South Korea, it has also been a long-established practice to lay-off female employees upon marriage.[125] A study by Professor Linda C. Babcock in her book Women Don't Ask shows that men are eight times more likely to ask for a pay raise, suggesting that pay inequality may be partly a result of behavioral differences between the sexes.[126] However, studies generally find that a portion of the gender pay gap remains unexplained after accounting for factors assumed to influence earnings; the unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.[127]

Estimates of the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap vary. The OECD estimated that approximately 30% of the gender pay gap across OECD countries is because of discrimination.[101] Australian research shows that discrimination accounts for approximately 60% of the wage differential between men and women.[128][129] Studies examining the gender pay gap in the United States show that a much of the wage differential remains unexplained, after controlling for factors affecting pay. One study of college graduates found that the portion of the pay gap unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is five percent one year after graduating and 12% a decade after graduation.[130][131][132][133] A study by the American Association of University Women found that women graduates in the United States are paid less than men doing the same work and majoring in the same field.[134]

Wage discrimination is theorized as contradicting the economic concept of supply and demand, which states that if a good or service (in this case, labor) is in demand and has value it will find its price in the market. If a worker offered equal value for less pay, supply and demand would indicate a greater demand for lower-paid workers. If a business hired lower-wage workers for the same work, it would lower its costs and enjoy a competitive advantage. According to supply and demand, if women offered equal value demand (and wages) should rise since they offer a better price (lower wages) for their service than men do.[136]

Research at Cornell University and elsewhere indicates that mothers in the United States are less likely to be hired than equally qualified fathers and, if hired, receive a lower salary than male applicants with children.[107][108][137][138][109][110] The OECD found that "a significant impact of children on women's pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States".[139] Fathers earn $7,500 more, on average, than men without children do.[140]

There is research to suggest that the gender wage gap leads to big losses for the economy.[141]

Causes for wage discrimination

The non-adjusted gender pay gap (the difference without taking into account differences in working hours, occupations, education, and work experience) is not itself a measure of discrimination. Rather, it combines differences in the average pay of women and men to serve as a barometer of comparison. Differences in pay are caused by:

- occupational segregation (with more men in higher paid industries and women in lower paid industries),

- vertical segregation (fewer women in senior, and hence better paying positions),

- ineffective equal pay legislation,

- women's overall paid working hours, and

- barriers to entry into the labor market (such as education level and single parenting rate).[142]

Some variables that help explain the non-adjusted gender pay gap include economic activity, working time, and job tenure.[142] Gender-specific factors, including gender differences in qualifications and discrimination, overall wage structure, and the differences in remuneration across industry sectors all influence the gender pay gap.[143]

Eurostat estimated in 2016 that after allowing for average characteristics of men and women, women still earn 11.5% less than men. Since this estimate accounts for average differences between men and women, it is an estimation of the unexplained gender pay gap (i.e., that which cannot be accounted for by factors such as differences in profession).[144]

Glass ceiling effect

"The popular notion of glass ceiling effects implies that gender (or other) disadvantages are stronger at the top of the hierarchy than at lower levels and that these disadvantages become worse later in a person's career."[145]

In the United States, women account for 52% of the overall labor force, but make up only three percent of corporate CEOs and top executives.[146] Some researchers see the root cause of this situation in the tacit discrimination based on gender, conducted by current top executives and corporate directors (primarily male), and "the historic absence of women in top positions", which "may lead to hysteresis, preventing women from accessing powerful, male-dominated professional networks, or same-sex mentors".[146] The glass ceiling effect is noted as being especially persistent for women of color. According to a report, "women of colour perceive a 'concrete ceiling' and not simply a glass ceiling".[146]

In the economics profession, it has been observed that women are more inclined than men to dedicate their time to teaching and service. Since continuous research work is crucial for promotion, "the cumulative effect of small, contemporaneous differences in research orientation could generate the observed significant gender difference in promotion".[147] In the high-tech industry, research shows that, regardless of the intra-firm changes, "extra-organizational pressures will likely contribute to continued gender stratification as firms upgrade, leading to the potential masculinization of skilled high-tech work".[148]

The United Nations asserts that "progress in bringing women into leadership and decision making positions around the world remains far too slow".[149]

Potential remedies

Research by David Matsa and Amalia Miller suggests that a remedy to the glass ceiling could be increasing the number of women on corporate boards, which could lead to increases in the number of women working in top management positions.[146] The same research suggests that this could also result in a "feedback cycle in which the presence of more female managers increases the qualified pool of potential female board members (for the companies they manage, as well as other companies), leading to greater female board membership and then further increases in female executives".[149]

Weight-based sexism

A 2009 study found that being overweight harms women's career advancement, but presents no barrier for men. Overweight women were significantly underrepresented among company bosses, making up between five and 22% of female CEOs. However, the proportion of overweight male CEOs was between 45% and 61%, over-representing overweight men. On the other hand, approximately five percent of CEOs were obese among both genders. The author of the study stated that the results suggest that "the 'glass ceiling effect' on women's advancement may reflect not only general negative stereotypes about the competencies of women but also weight bias that results in the application of stricter appearance standards to women."[150][151]

Transgender discrimination

Transgender people also experience significant workplace discrimination and harassment.[152] Unlike sex-based discrimination, refusing to hire (or firing) a worker for their gender identity or expression is not explicitly illegal in most U.S. states.[153] In June 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that federal civil rights law protects gay, lesbian and transgender workers. Writing for the majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote: "An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids."[154] The ruling however did not protect LGBT employees from being fired based on their sexual orientation or gender identity in businesses of 15 workers or less.[155]

In August 1995, Kimberly Nixon filed a complaint with the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal against Vancouver Rape Relief & Women's Shelter. Nixon, a trans woman, had been interested in volunteering as a counsellor with the shelter. When the shelter learned that she was transsexual, they told Nixon that she would not be allowed to volunteer with the organization. Nixon argued that this constituted illegal discrimination under Section 41 of the British Columbia Human Rights Code. Vancouver Rape Relief countered that individuals are shaped by the socialization and experiences of their formative years, and that Nixon had been socialized as a male growing up, and that, therefore, Nixon would not be able to provide sufficiently effective counselling to the female born women that the shelter served. Nixon took her case to the Supreme Court of Canada, which refused to hear the case.[156]

Objectification

In social philosophy, objectification is the act of treating a person as an object or thing. Objectification plays a central role in feminist theory, especially sexual objectification.[157] Feminist writer and gender equality activist Joy Goh-Mah argues that by being objectified, a person is denied agency.[158] According to the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, a person might be objectified if one or more of the following properties are applied to them:[159]

- Instrumentality: treating the object as a tool for another's purposes: "The objectifier treats the object as a tool of his or her purposes."

- Denial of autonomy: treating the object as lacking in autonomy or self-determination: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in autonomy and self-determination."

- Inertness: treating the object as lacking in agency or activity: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in agency, and perhaps also in activity."

- Fungibility: treating the object as interchangeable with other objects: "The objectifier treats the object as interchangeable (a) with other objects of the same type, and/or (b) with objects of other types."

- Violability: treating the object as lacking in boundary integrity and violable: "The objectifier treats the object as lacking in boundary integrity, as something that it is permissible to break up, smash, break into."

- Ownership: treating the object as if it can be owned, bought, or sold: "The objectifier treats the object as something that is owned by another, can be bought or sold, etc."

- Denial of subjectivity: treating the object as if there is no need for concern for its experiences or feelings: "The objectifier treats the object as something whose experience and feelings (if any) need not be taken into account."

Rae Helen Langton, in Sexual Solipsism: Philosophical Essays on Pornography and Objectification, proposed three more properties to be added to Nussbaum's list:[157][160]

- Reduction to Body: the treatment of a person as identified with their body, or body parts;

- Reduction to Appearance: the treatment of a person primarily in terms of how they look, or how they appear to the senses;

- Silencing: the treatment of a person as if they are silent, lacking the capacity to speak.

According to objectification theory, objectification can have important repercussions on women, particularly young women, as it can negatively impact their psychological health and lead to the development of mental disorders, such as unipolar depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders.[161]

In advertising

While advertising used to portray women and men in obviously stereotypical roles (e.g., as a housewife, breadwinner), in modern advertisements, they are no longer solely confined to their traditional roles. However, advertising today still stereotypes men and women, albeit in more subtle ways, including by sexually objectifying them.[162] Women are most often targets of sexism in advertising.[citation needed] When in advertisements with men they are often shorter and put in the background of images, shown in more "feminine" poses, and generally present a higher degree of "body display".[163]

Today, some countries (for example Norway and Denmark) have laws against sexual objectification in advertising.[164] Nudity is not banned, and nude people can be used to advertise a product if they are relevant to the product advertised. Sol Olving, head of Norway's Kreativt Forum (an association of the country's top advertising agencies) explained, "You could have a naked person advertising shower gel or a cream, but not a woman in a bikini draped across a car".[164]

Other countries continue to ban nudity (on traditional obscenity grounds), but also make explicit reference to sexual objectification, such as Israel's ban of billboards that "depicts sexual humiliation or abasement, or presents a human being as an object available for sexual use".[165]

Pornography

Anti-pornography feminist Catharine MacKinnon argues that pornography contributes to sexism by objectifying women and portraying them in submissive roles.[166] MacKinnon, along with Andrea Dworkin, argues that pornography reduces women to mere tools, and is a form of sex discrimination.[167] The two scholars highlight the link between objectification and pornography by stating:

We define pornography as the graphic sexually explicit subordination of women through pictures and words that also includes (i) women are presented dehumanized as sexual objects, things, or commodities; or (ii) women are presented as sexual objects who enjoy humiliation or pain; or (iii) women are presented as sexual objects experiencing sexual pleasure in rape, incest or other sexual assault; or (iv) women are presented as sexual objects tied up, cut up or mutilated or bruised or physically hurt; or (v) women are presented in postures or positions of sexual submission, servility, or display; or (vi) women's body parts—including but not limited to vaginas, breasts, or buttocks—are exhibited such that women are reduced to those parts; or (vii) women are presented being penetrated by objects or animals; or (viii) women are presented in scenarios of degradation, humiliation, injury, torture, shown as filthy or inferior, bleeding, bruised, or hurt in a context that makes these conditions sexual."[168]

Robin Morgan and Catharine MacKinnon suggest that certain types of pornography also contribute to violence against women by eroticizing scenes in which women are dominated, coerced, humiliated or sexually assaulted.[169][170]

Some people opposed to pornography, including MacKinnon, charge that the production of pornography entails physical, psychological, and economic coercion of the women who perform and model in it.[171][172][173] Opponents of pornography charge that it presents a distorted image of sexual relations and reinforces sexual myths; it shows women as continually available and willing to engage in sex at any time, with any person, on their terms, responding positively to any requests.

MacKinnon writes:

Pornography affects people's belief in rape myths. So for example if a woman says "I didn't consent" and people have been viewing pornography, they believe rape myths and believe the woman did consent no matter what she said. That when she said no, she meant yes. When she said she didn't want to, that meant more beer. When she said she would prefer to go home, that means she's a lesbian who needs to be given a good corrective experience. Pornography promotes these rape myths and desensitizes people to violence against women so that you need more violence to become sexually aroused if you're a pornography consumer. This is very well documented.[174]

Defenders of pornography and anti-censorship activists (including sex-positive feminists) argue that pornography does not seriously impact a mentally healthy individual, since the viewer can distinguish between fantasy and reality.[175] Some also contend that both men and women are objectified in pornography, particularly sadistic or masochistic pornography in which men are objectified and sexually used by women.[176]

Prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual relations for payment.[177][178] Sex workers are often objectified and are seen as existing only to serve clients, thus calling their sense of agency into question. There is a prevailing notion that because they sell sex professionally, prostitutes automatically consent to all sexual contact.[179] As a result, sex workers face higher rates of violence and sexual assault. This is often dismissed, ignored and not taken seriously by authorities.[179]

In many countries, prostitution is dominated by brothels or pimps, who often claim ownership over sex workers. This sense of ownership furthers the concept that sex workers are void of agency.[180] This is literally the case in instances of sexual slavery.

Various authors have argued that female prostitution is based on male sexism that condones the idea that unwanted sex with a woman is acceptable, that men's desires must be satisfied, and that women are coerced into and exist to serve men sexually.[181][182][183][184] The European Women's Lobby condemned prostitution as "an intolerable form of male violence".[185]

Carole Pateman writes that:

Prostitution is the use of a woman's body by a man for his own satisfaction. There is no desire or satisfaction on the part of the prostitute. Prostitution is not mutual, pleasurable exchange of the use of bodies, but the unilateral use of a woman's body by a man in exchange for money.[186]

Media portrayals

Some scholars believe that media portrayals of demographic groups can both maintain and disrupt attitudes and behaviors toward those groups.[187][page needed][188][189][page needed] According to Susan Douglas: "Since the early 1990s, much of the media have come to overrepresent women as having made it-completely-in the professions, as having gained sexual equality with men, and having achieved a level of financial success and comfort enjoyed primarily by Tiffany's-encrusted doyennes of Laguna Beach."[190] These images may be harmful, particularly to women and racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, a study of African American women found they feel that media portrayals of themselves often reinforce stereotypes of this group as overly sexual and idealize images of lighter-skinned, thinner African American women (images African American women describe as objectifying).[191] In a recent analysis of images of Haitian women in the Associated Press photo archive from 1994 to 2009, several themes emerged emphasizing the "otherness" of Haitian women and characterizing them as victims in need of rescue.[192]

In an attempt to study the effect of media consumption on males, Samantha and Bridges found an effect on body shame, though not through self-objectification as it was found in comparable studies of women. The authors conclude that the current measures of objectification were designed for women and do not measure men accurately.[193] Another study found a negative effect on eating attitudes and body satisfaction of consumption of beauty and fitness magazines for women and men respectively but again with different mechanisms, namely self-objectification for women and internalization for men.[194]

Sexist jokes

Frederick Attenborough argues that sexist jokes can be a form of sexual objectification, which reduce the butt of the joke to an object. They not only objectify women, but can also condone violence or prejudice against women.[195] "Sexist humor—the denigration of women through humor—for instance, trivializes sex discrimination under the veil of benign amusement, thus precluding challenges or opposition that nonhumorous sexist communication would likely incur."[196] A study of 73 male undergraduate students by Ford found that "sexist humor can promote the behavioral expression of prejudice against women amongst sexist men".[196] According to the study, when sexism is presented in a humorous manner it is viewed as tolerable and socially acceptable: "Disparagement of women through humor 'freed' sexist participants from having to conform to the more general and more restrictive norms regarding discrimination against women."[196]

Gender identity discrimination

Gender discrimination is discrimination based on actual or perceived gender identity.[197][page needed] Gender identity is "the gender-related identity, appearance, or mannerisms or other gender-related characteristics of an individual, with or without regard to the individual's designated sex at birth".[197][page needed] Gender discrimination is theoretically different from sexism.[198][page needed] Whereas sexism is prejudice based on biological sex, gender discrimination specifically addresses discrimination towards gender identities, including third gender, genderqueer, and other non-binary identified people.[7] It is especially attributed to how people are treated in the workplace,[8] and banning discrimination on the basis of gender identity and expression has emerged as a subject of contention in the American legal system.[199]

According to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service, "although the majority of federal courts to consider the issue have concluded that discrimination on the basis of gender identity is not sex discrimination, there have been several courts that have reached the opposite conclusion".[197] Hurst states that "[c]ourts often confuse sex, gender and sexual orientation, and confuse them in a way that results in denying the rights not only of gays and lesbians, but also of those who do not present themselves or act in a manner traditionally expected of their sex".[200]

Oppositional sexism

Oppositional sexism is a term coined by transfeminist author Julia Serano, who defined oppositional sexism as "the belief that male and female are rigid, mutually exclusive categories".[201] Oppositional sexism plays a vital role in a number of social norms, such as cisnormativity and heteronormativity.

Oppositional sexism normalizes masculine expression in males and feminine expression in females while simultaneously demonizing femininity in males and masculinity in females. This concept plays a crucial role in supporting cissexism, the social norm that views cisgender people as both natural and privileged as opposed to transgender people.[202]

The idea of having two, opposite genders is tied to sexuality through what gender theorist Judith Butler calls a "compulsory practice of heterosexuality".[202] Because oppositional sexism is tied to heteronormativity in this way, non-heterosexuals are seen as breaking gender norms.[202]

The concept of opposite genders sets a "dangerous precedent", according to Serano, where "if men are big then women must be small; and if men are strong then women must be weak".[201] The gender binary and oppositional norms work together to support "traditional sexism", the belief that femininity is inferior to and serves masculinity.[202]

Serano states that oppositional sexism works in tandem with "traditional sexism". This ensures that "those who are masculine have power over those who are feminine, and that only those that are born male will be seen as authentically masculine."[201]

Transgender discrimination

Transgender discrimination is discrimination towards peoples whose gender identity differs from the social expectations of the biological sex they were born with.[203] Forms of discrimination include but are not limited to identity documents not reflecting one's gender, sex-segregated public restrooms and other facilities, dress codes according to binary gender codes, and lack of access to and existence of appropriate health care services.[204] In a recent adjudication, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) concluded that discrimination against a transgender person is sex discrimination.[204]

The 2008–09 National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS)—a U.S. study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force in collaboration with the National Black Justice Coalition that was, at its time, the most extensive survey of transgender discrimination—showed that Black transgender people in the United States suffer "the combination of anti-transgender bias and persistent, structural and individual racism" and that "black transgender people live in extreme poverty that is more than twice the rate for transgender people of all races (15%), four times the general Black population rate (9%) and over eight times the general US population rate (4%)".[205] Further discrimination is faced by gender nonconforming individuals, whether transitioning or not, because of displacement from societally acceptable gender binaries and visible stigmatization. According to the NTDS, transgender gender nonconforming (TGNC) individuals face between eight percent and 15% higher rates of self and social discrimination and violence than binary transgender individuals. Lisa R. Miller and Eric Anthony Grollman found in their 2015 study that "gender nonconformity may heighten trans people's exposure to discrimination and health-harming behaviors. Gender nonconforming trans adults reported more events of major and everyday transphobic discrimination than their gender conforming counterparts."[206]

In another study conducted in collaboration with the League of United Latin American Citizens, Latino/a transgender people who were non-citizens were most vulnerable to harassment, abuse and violence.[207]

An updated version of the NTDS survey, called the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, was published in December 2016.[208]

Examples

Child and forced marriage

A child marriage is a marriage where one or both spouses are under 18, a practice that disproportionately affects women.[209][210] Child marriages are most common in South Asia, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, but occur in other parts of the world, too. The practice of marrying young girls is rooted in patriarchal ideologies of control of female behavior and is also sustained by traditional practices such as dowry and bride price.[211] Child marriage is strongly connected with protecting female virginity.[212] UNICEF states that:[209]

Marrying girls under 18 years old is rooted in gender discrimination, encouraging premature and continuous child bearing and giving preference to boys' education. Child marriage is also a strategy for economic survival as families marry off their daughters at an early age to reduce their economic burden.

Consequences of child marriage include restricted education and employment prospects, increased risk of domestic violence, child sexual abuse, pregnancy and birth complications, and social isolation.[210][212] Early and forced marriage are defined as forms of modern-day slavery by the International Labour Organization.[213] In some cases, a woman or girl who has been raped may be forced to marry her rapist to restore the honor of her family;[214][215] marriage by abduction, a practice in which a man abducts the woman or girl whom he wishes to marry and rapes her to force the marriage is common in Ethiopia.[216][217][218]

Military

Conscription, or compulsory military service, has been criticized as sexist.[219]: 102 [220] During the Modern era, prior to the late 20th century, mostly men were subjected to conscription, although there were several instances of conscription of women in Antiquity and the Middle Ages.[221][222][219]: 255 [223][224][225][226] Today most countries still require only men to serve in the military.

In his book The Second Sexism: Discrimination Against Men and Boys (2012), philosopher David Benatar states that "[t]he prevailing assumption is that where conscription is necessary, it is only men who should be conscripted and, similarly, that only males should be forced into combat". This, he believes, "is a sexist assumption".[219]: 102 Anthropologist Ayse Gül Altinay has commented that "given equal suffrage rights, there is no other citizenship practice that differentiates as radically between men and women as compulsory male conscription".[227]: 34

Only nine countries conscript women into their armed forces: China, Eritrea, Israel, Libya, Malaysia, North Korea, Norway, Peru, and Taiwan.[228][229] Other countries—such as Finland, Turkey, and Singapore—still use a system of conscription which requires military service from men only, although women may serve voluntarily. In 2014, Norway became the first NATO country to introduce obligatory military service for women as an act of gender equality[229][230] and in 2015, the Dutch government started preparing a gender-neutral draft law.[231] The gender selective draft has been challenged in the United States.[232]

Conditions in the military have been described as "sexually abusive" and the "sexual persecution" of women.[233] Relentless sexist ridicule, hostility, and sexual harassment has been frequently reported.[234][235] Women in the military are more likely to be raped by a male fellow soldier than killed by the enemy.[236][237][238] Prosecution of the reported crimes fails to move forward, as the Pentagon claimed it would undermine the leadership of the commanders.[239][240]

Domestic violence

Although the exact rates are widely disputed, there is a large body of cross-cultural evidence that domestic violence is mostly committed by men against women.[241][242][243] In addition, there is a broad consensus that women are more often subjected to severe forms of abuse and are more likely to be injured by an abusive partner.[242][243] The United Nations recognizes domestic violence as a form of gender-based violence, which it describes as a human rights violation, and the result of sexism.[244]

Domestic violence is tolerated and even legally accepted in many parts of the world. For instance, in 2010, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)'s Supreme Court ruled that a man has the right to discipline his wife and children physically if he does not leave visible marks.[245] In 2015, Equality Now drew attention to a section of the Penal Code of Northern Nigeria, titled Correction of Child, Pupil, Servant or Wife which reads: "(1) Nothing is an offence which does not amount to the infliction of grievous hurt upon any persons which is done: (...) (d) by a husband for the purpose of correcting his wife, such husband and wife being subject to any native law or custom in which such correction is recognized as lawful."[246]

Honor killings are another form of domestic violence practiced in several parts of the world, and their victims are predominantly women.[247] Honor killings can occur because of refusal to enter into an arranged marriage, maintaining a relationship relatives disapprove of, extramarital sex, becoming the victim of rape, dress seen as inappropriate, or homosexuality.[248][249][250] The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime states that, "[h]onour crimes, including killing, are one of history's oldest forms of gender-based violence".[251]

According to a report of the Special Rapporteur submitted to the 58th session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights concerning cultural practices in the family that reflect violence against women:

The Special Rapporteur indicated that there had been contradictory decisions with regard to the honor defense in Brazil, and that legislative provisions allowing for partial or complete defense in that context could be found in the penal codes of Argentina, Ecuador, Egypt, Guatemala, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Peru, Syria, Venezuela, and the Palestinian National Authority.[252]

Practices such as honor killings and stoning continue to be supported by mainstream politicians and other officials in some countries. In Pakistan, after the 2008 Balochistan honor killings in which five women were killed by tribesmen of the Umrani Tribe of Balochistan, Pakistani federal minister for Postal Services Israr Ullah Zehri defended the practice:[253] "These are centuries-old traditions, and I will continue to defend them. Only those who indulge in immoral acts should be afraid."[254] Following the 2006 case of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani (which has placed Iran under international pressure for its stoning sentences), Mohammad-Javad Larijani, a senior envoy and chief of Iran's Human Rights Council, defended the practice of stoning; he claimed it was a "lesser punishment" than execution, because it allowed those convicted a chance at survival.[255]

Dowry deaths result from the killing of women who are unable to pay the high dowry price for their marriage. According to Amnesty International, "the ongoing reality of dowry-related violence is an example of what can happen when women are treated as property".[256]

Education

Women have traditionally had limited access to higher education.[257][page needed] In the past, when women were admitted to higher education, they were encouraged to major in less-scientific subjects; the study of English literature in American and British colleges and universities was instituted as a field considered suitable to women's "lesser intellects".[258][page needed]

Educational specialties in higher education produce and perpetuate inequality between men and women.[259] Disparity persists particularly in computer and information science, where in the US women received only 21% of the undergraduate degrees, and in engineering, where women obtained only 19% of the degrees in 2008.[260] Only one out of five of physics doctorates in the US are awarded to women, and only about half those women are American.[261] Of all the physics professors in the country, only 14% are women.[261] As of 2019, women account for just 27% of all workers in STEM fields, and on average earn almost 20% less than men in the same industries.[262]

World literacy is lower for females than for males. Data from The World Factbook shows that 79.7% of women are literate, compared to 88.6% of men (aged 15 and over).[263] In some parts of the world, girls continue to be excluded from proper public or private education. In parts of Afghanistan, girls who go to school face serious violence from some local community members and religious groups.[264] According to 2010 UN estimates, only Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen had less than 90 girls per 100 boys at school.[265] Jayachandran and Lleras-Muney's study of Sri Lankan economic development has suggested that increases in the life expectancy for women encourages educational investment because a longer time horizon increases the value of investments that pay out over time.[266]

Educational opportunities and outcomes for women have greatly improved in the West. Since 1991, the proportion of women enrolled in college in the United States has exceeded the enrollment rate for men, and the gap has widened over time.[267] As of 2007[update], women made up the majority—54%—of the 10.8 million college students enrolled in the United States.[268] However, research by Diane Halpern has indicated that boys receive more attention, praise, blame and punishment in the grammar-school classroom,[269] and "this pattern of more active teacher attention directed at male students continues at the postsecondary level".[270] Over time, female students speak less in a classroom setting.[271] Teachers also tend to spend more time supporting the academic achievements of girls.[272]

Boys are frequently diagnosed with ADHD, which some see as a result of school systems being more likely to apply these labels to males.[273] A recent study by the OECD in over 60 countries found that teachers give boys lower grades for the same work. The researchers attribute this to stereotypical ideas about boys and recommend teachers to be aware of this gender bias.[274] One study found that students give female professors worse evaluation scores than male professors, even though the students appear to do as well under female professors as male professors.[275]

Gender bias and gender-based discrimination still permeate the education process in many settings. For example, in the teaching and learning process, including differential engagement, expectations and interactions by teachers with their male and female students, as well as gender stereotypes in textbooks and learning materials. There has been a lack in adequate resources and infrastructure to ensure safe and enabling learning environments, and insufficient policy, legal and planning frameworks, that respect, protect and fulfil the right to education.[276]

Fashion

Feminists argue that clothing and footwear fashion have been oppressive to women, restricting their movements, increasing their vulnerability, and endangering their health.[277] Using thin models in the fashion industry has encouraged the development of bulimia and anorexia nervosa, as well as locking female consumers into false feminine identities.[278]

The assignment of gender-specific baby clothes can instill in children a belief in negative gender stereotypes.[279] One example is the assignment in some countries of the color pink to girls and blue to boys. The fashion is recent one. At the beginning of the 20th century the trend was the opposite: blue for girls and pink for boys.[280] In the early 1900s, The Women's Journal wrote that "pink being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl". DressMaker magazine also explained that "[t]he preferred colour to dress young boys in is pink. Blue is reserved for girls as it is considered paler, and the more dainty of the two colours, and pink is thought to be stronger (akin to red)".[281] Today, in many countries, it is considered inappropriate for boys to wear dresses and skirts, but this is also a relatively recent view. From the mid-16th century[282] until the late 19th or early 20th century, young boys in the Western world were unbreeched and wore gowns or dresses until an age that varied between two and eight.[283]

Laws that dictate how women must dress are seen by many international human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, as gender discrimination.[284] In many countries, women face violence for failing to adhere to certain dress codes, whether by the authorities (such as the religious police), family members, or the community.[285][286] Amnesty International states:

Interpretations of religion, culture, or tradition cannot justify imposing rules about dress on those who choose to dress differently. States should take measures to protect individuals from being coerced to dress in specific ways by family members, community or religious groups or leaders.[284]

The production process also faces criticism for sexist practices. In the garment industry, approximately 80 percent of workers are female.[287] Much garment production is located in Asia because of low labor costs. Women who work in these factories are sexually harassed by managers and male workers, paid low wages, and discriminated against when pregnant.[288]

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons". The WHO further states, "The practice has no health benefits for girls and women and [can] cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths."[289] It "is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women" and "constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women".[289] The European Parliament stated in a 2014 resolution that the practice "clearly goes against the European founding value of equality between women and men and maintains traditional values according to which women are seen as the objects and properties of men".[290]

Gendercide and forced sterilization

Female infanticide is the killing of newborn female children, while female selective abortion is the terminating of a pregnancy based upon the female sex of the fetus. Gendercide is the systematic killing of members of a specific gender and it is an extreme form of gender-based violence.[291][292][293] Female infanticide is more common than male infanticide, and is especially prevalent in South Asia, in countries such as China, India and Pakistan.[292][294][295] Recent studies suggest that over 90 million women and girls are missing in China and India as a result of infanticide.[296][297]

Sex-selective abortion involves terminating a pregnancy based upon the predicted sex of the baby. The abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where a culture values male children over females,[298] such as parts of East Asia and South Asia (China, India, Korea), the Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia), and Western Balkans (Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo).[298][299] One reason for this preference is that males are seen as generating more income than females. The trend has grown steadily over the previous decade, and may result in a future shortage of women.[300]

Forced sterilization and forced abortion are also forms of gender-based violence.[291] Forced sterilization was practiced during the first half of the 20th century by many Western countries and there are reports of this practice being currently employed in some countries, such as Uzbekistan and China.[301][302][303][304]

In China, the one child policy interacting with the low status of women has been deemed responsible for many abuses, such as female infanticide, sex-selective abortion, abandonment of baby girls, forced abortion, and forced sterilization.[305][306]

In India, the custom of dowry is strongly related to female infanticide, sex-selective abortion, abandonment and mistreatment of girls.[307] Such practices are especially present in the northwestern part of the country: Jammu and Kashmir, Haryana, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Delhi. (See Female foeticide in India and Female infanticide in India).

Legal justice and regulations

In several Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries the legal testimony of a woman is worth legally half of that of a man (see Status of women's testimony in Islam). Such countries include: Algeria (in criminal cases), Bahrain (in Sharia courts), Egypt (in family courts), Iran (in most cases), Iraq (in some cases), Jordan (in Sharia courts), Kuwait (in family courts), Libya (in some cases), Morocco (in family cases), Palestine (in cases related to marriage, divorce and child custody), Qatar (in family law matters), Syria (in Sharia courts), United Arab Emirates (in some civil matters), Yemen (not allowed to testify at all in cases of adultery and retribution), and Saudi Arabia.[308][309] Such laws have been criticized by Human Rights Watch and Equality Now as being discriminatory towards women.[310][311]

The criminal justice system in many common law countries has also been accused of discriminating against women. Provocation is, in many common law countries, a partial defense to murder, which converts what would have been murder into manslaughter. It is meant to be applied when a person kills in the "heat of passion" upon being "provoked" by the behavior of the victim. This defense has been criticized as being gendered, favoring men, because of it being used disproportionately in cases of adultery, and other domestic disputes when women are killed by their partners. As a result of the defense exhibiting a strong gender bias, and being a form of legitimization of male violence against women and minimization of the harm caused by violence against women, it has been abolished or restricted in several jurisdictions.[312][313]

The traditional leniency towards crimes of passion in Latin American countries has been deemed to have its origin in the view that women are property.[314] In 2002, Widney Brown, advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, stated that, "[S]o-called crimes of passion have a similar dynamic [to honor killings] in that the women are killed by male family members and the crimes are perceived as excusable or understandable."[314] The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has called for "the elimination of discriminatory provisions in the legislation, including mitigating factors for 'crimes of passion'."[315]

In the United States, some studies have shown that for identical crimes, men are given harsher sentences than women. Controlling for arrest offense, criminal history, and other pre-charge variables, sentences are over 60% heavier for men. Women are more likely to avoid charges entirely, and to avoid imprisonment if convicted.[316][317] The gender disparity varies according to the nature of the case. For example, the gender gap is less pronounced in fraud cases than in drug trafficking and firearms. This disparity occurs in US federal courts, despite guidelines designed to avoid differential sentencing.[318] The death penalty may also suffer from gender bias. According to Shatz and Shatz, "[t]he present study confirms what earlier studies have shown: that the death penalty is imposed on women relatively infrequently and that it is disproportionately imposed for the killing of women".[319]

There have been several reasons postulated for the gender criminal justice disparity in the United States. One of the most common is the expectation that women are predominantly care-givers.[316][317][318] Other possible reasons include the "girlfriend theory" (whereby women are seen as tools of their boyfriends),[317] the theory that female defendants are more likely to cooperate with authorities,[317] and that women are often successful at turning their violent crime into victimhood by citing defenses such as postpartum depression or battered wife syndrome.[320] However, none of these theories account for the total disparity,[317] and sexism has also been suggested as an underlying cause.[321]

Gender discrimination also helps explain the differences between trial outcomes in which some female defendants are sentenced to death and other female defendants are sentenced to lesser punishments. Phillip Barron argues that female defendants are more likely to be sentenced to death for crimes that violate gender norms, such as killing children or killing strangers.[322]

Transgender people face widespread discrimination while incarcerated. They are generally housed according to their legal birth sex, rather than their gender identity. Studies have shown that transgender people are at an increased risk for harassment and sexual assault in this environment. They may also be denied access to medical procedures related to their reassignment.[323]

Some countries use stoning as a form of capital punishment. According to Amnesty International, the majority of those stoned are women and women are disproportionately affected by stoning because of sexism in the legal system.[324]

One study found that:

[O]n average, women receive lighter sentences in comparison with men ... roughly 30% of the gender differences in incarceration cannot be explained by the observed criminal characteristics of offense and offender. We also find evidence of considerable heterogeneity across judges in their treatment of female and male offenders. There is little evidence, however, that tastes for gender discrimination are driving the mean gender disparity or the variance in treatment between judges.[325]

A 2017 study by Knepper found that "female plaintiffs filing workplace sex discrimination claims are substantially more likely to settle and win compensation whenever a female judge is assigned to the case. Additionally, female judges are 15 percentage points less likely than male judges to grant motions filed by defendants, which suggests that final negotiations are shaped by the emergence of the bias."[326]

Reproductive rights

The United Nations Population Fund writes that, "Family planning is central to gender equality and women's empowerment".[327] Women in many countries around the world are denied medical and informational services related to reproductive health, including access to pregnancy care, family planning, and contraception.[327][328] In countries with very strict abortion laws (particularly in Latin America) women who suffer miscarriages are often investigated by the police under suspicion of having deliberately provoked the miscarriage and are sometimes jailed,[329] a practice which Amnesty International called a "ruthless campaign against women's rights".[330] Doctors may be reluctant to treat pregnant women who are very ill, because they are afraid the treatment may result in fetal loss.[331] According to Amnesty International, "Discriminatory attitudes towards women and girls also means access to sex education and contraceptives are near impossible [in El Salvador]".[332] The organization has also criticized laws and policies which require the husband's consent for a woman to use reproductive health services as being discriminatory and dangerous to women's health and life: "[F]or the woman who needs her husband's consent to get contraception, the consequences of discrimination can be serious—even fatal".[333]

Sexual assault and treatment of victims

Research by Lisak and Roth into factors motivating perpetrators of sexual assault, including rape, against women revealed a pattern of hatred towards women and pleasure in inflicting psychological and physical trauma, rather than sexual interest.[334] Mary Odem and Peggy Reeves Sanday posit that rape is the result not of pathology but of systems of male dominance, cultural practices and beliefs.[335]

Odem, Jody Clay-Warner, and Susan Brownmiller argue that sexist attitudes are propagated by a series of myths about rape and rapists.[336]: 130–140 [337] They state that in contrast to those myths, rapists often plan a rape before they choose a victim[336] and acquaintance rape (not assault by a stranger) is the most common form of rape.[336]: xiv [338] Odem also asserts that these rape myths propagate sexist attitudes about men, by perpetuating the belief that men cannot control their sexuality.[336]

Sexism can promote the stigmatization of women and girls who have been raped and inhibit recovery.[214] In many parts of the world, women who have been raped are ostracized, rejected by their families, subjected to violence, and—in extreme cases—may become victims of honor killings because they are deemed to have brought shame upon their families.[214][339]

The criminalization of marital rape is very recent, having occurred during the past few decades; in many countries it is still legal. Several countries in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia made spousal rape illegal before 1970; other European countries and some English-speaking countries outside Europe outlawed it later, mostly in the 1980s and 1990s;[340] some countries outlawed it in the 2000s.[341] The WHO wrote that: "Marriage is often used to legitimize a range of forms of sexual violence against women. The custom of marrying off young children, particularly girls, is found in many parts of the world. This practice—legal in many countries—is a form of sexual violence, since the children involved are unable to give or withhold their consent".[214]

In countries where fornication or adultery are illegal, victims of rape can be charged criminally.[342]

War rape

Sexism is manifested by the crime of rape targeting women civilians and soldiers, committed by soldiers, combatants or civilians during armed conflict, war or military occupation. This arises from the long tradition of women being seen as sexual booty and from the misogynistic culture of military training.[343][344]

See also

- Ambivalent sexism

- Antifeminism

- Androcide