Femminiello

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (October 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

Femminielli or femmenielli (singular femminiello, also spelled as femmeniello) are a population of people who embody a third gender role in traditional Neapolitan culture.[4][5] This term is culturally distinct from trans woman, and has its own cultural significance and practices, often including prostitution.[5] This term is not derogatory; instead femminielli are traditionally believed to bring good luck.[4][5]

Etymology

[edit]Derived from Neapolitan femmena 'woman' with the suffix -iello, which is a diminutive term of endearment, with a masculine -o ending, the term roughly translates to 'little women-men'. Neither derogatory nor an insult, it is instead used in a descriptive capacity.[1][2]

Contemporary

[edit]There has been dispute about whether it is accurate to insert the Neapolitan femminiello within the contemporary term transgender, usually adopted in Northern European and North American contexts.[6] Despite conflation of the term in mainstream media,[7][4] historians maintain that an important aspect of i femminielli is that they are decidedly male despite their female gender role.[5]

Many consider femminiello to be a peculiar gender expression deeply tied to the history of the city of Naples, despite a widespread sexual binarism.[8] The cultural roots that this phenomenon is embedded in confer to the femminiello a socially legitimized status, including holding particular familial, ceremonial, and cultural roles.[2] Achille della Ragione, a Neapolitan scholar, has written of social aspects of femminielli. "[The femminiello] is usually the youngest male child, 'mother's little darling,' ... he is useful, he does chores, runs errands and watches the kids."[5]

In 2009 the term femminiello gained some notoriety in Italian media after a Naples native femminiello Camorra mobster Ketty Gabriele was arrested. Gabriele, who had engaged in prostitution prior to becoming a capo, has been referred to both as a femminiello[4] and transessuale or trans[7][9] in Italian media.

Some scholars, including Eugenio Zito of the University of Naples Federico II, propose that the femminielli "seem to confirm, in the field of gender identity, the postmodern idea of continuous modulation between the masculine and the feminine against their dichotomy."[8]

History

[edit]

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (October 2024) |

The constant references in many sources to the ancient rituals behind the presence of the femminiello in Naples require little comment. The links to ancient Greek mythology are numerous: for example, Hermaphroditus, who possessed the beauty of their mother, Aphrodite, and the strength of their father, Hermes; or Tiresias, the blind prophet of Thebes, famous for being transformed into a woman for seven years. Both of these personages and others in many cultures in the world are presumed to possess something that others do not: the wise equilibrium that comes from knowing both worlds, masculine and feminine.[5][10]

The history of the femminielli may trace back to a real, non-mythological group: the Galli (also called Galloi or Gallae, singular gallus), a significant portion of the ancient priesthood of the mother goddess Cybele and her consort Attis. This tradition began in Phrygia (where Turkey is today, part of Asia Minor), sometime before 300 BC.[11] After 205 BC, the tradition entered the city of Rome, and spread throughout the Roman Empire, as far north as London.[11] They were eunuchs who wore bright-colored feminine sacerdotal clothing, hairstyles or wigs, makeup, and jewelry, and used feminine mannerisms in their speech. They addressed one another by feminine titles, such as sister. There were other priests and priestesses of Cybele who were not eunuchs, so it would not have been necessary to become a gallus or eunuch in order to become a priest of Cybele. The Gallae were not ascetic but hedonistic, so castration was not about stopping sexual desires. Some Gallae would marry men, and others would marry women. The ways of the Gallae were more consistent with transgender people with gender dysphoria, which they relieved by voluntary castration, as the available form of sex reassignment surgery.[12][13][11]

Contemporaries who were not Gallae called them by masculine words, Galloi or Galli (plural), or Gallus (singular). Some historians interpret the Gallae as transgender, by modern terms, and think they would have called themselves by the feminine Gallae (plural) and Galla (singular).[12][13][14] The Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17 AD) says their name comes from the Gallus river in Phrygia;[15]

Phrygians and Romans believed the Gallae had spiritual powers to tell the future, bless homes, have power over wild animals, bring rain, and exorcise evil spirits. The Roman public viewed them with a mixture of awe and contempt, seeing them as practicing shocking foreign customs, so they were just as often honored as they were harassed and politically persecuted. They were not allowed to be Roman citizens, and vice versa.[16][11]

Ceremony

[edit]A ceremony called the matrimonio dei femminielli takes place in Torre Annunziata on Easter Monday, where a parade of femminielli dressed in wedding gowns and accompanied by a "husband" travel through the streets in horse-drawn carriages.[17]

Tradition

[edit]The femminiello in Campania enjoy a relatively privileged position thanks to their participation in some traditional events, such as Candelora al Santuario di Montevergine (Candlemas at the Sanctuary of Montevergine) in Avellino[18] or the Tammurriata, a traditional dance performed at the feast of Madonna dell'Arco in Sant'Anastasia.[19]

Generally femminielli are considered to bring good luck. For this reason, it is popular in the neighborhoods for a femminiello to hold a newborn baby, or participate in games such as bingo.[10] Above all the Tombola or Tombolata dei femminielli,[20] a popular game performed every year on 2 February, as the conclusive part of the Candlemas at the Sanctuary of Montevergine.

Theatre

[edit]In a stage production called La gatta Cenerentola ('The Cat Cinderella'), by Roberto De Simone, femmenielli play the roles of several important characters. Among the major scenes in this respect are the rosario dei femmenielli and il suicidio del femminiella.[21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "The Femminiello". portlandartmuseum.us. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ a b c "Naples Life,Death & Miracle". www.naplesldm.com. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

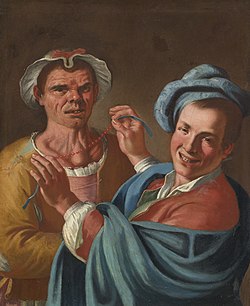

- ^ Lang, Nico (11 Jul 2016). "This 18th-Century Italian Painting Proves Gender Nonconformity Is Far From a Modern Invention". Slate. The Slate Group LLC.

- ^ a b c d Fulvio, Bufi (2009). "Presa Ketty, boss "femminiello" Comandava i pusher di Gomorra". Corriere della Sera (February 13, 2009): 19. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015.

Femminiello è una figura omosessuale (..) è una persona dall' aspetto effeminato o spesso un travestito. È rispettato e generalmente il femminiello viene considerato una persona che porta fortuna.

- ^ a b c d e f Jeff Matthews. "The Femminiello in Neapolitan Culture". Archived from the original on 2011-05-15.

- ^ Hochdorn, Alexander, Paolo F. Cottone and Dania Vallini (2011). Gender and discursive positioning: Doing transgender in highly normative contexts. 69th Conference of the International Council of Psychologists. 29 July - 2 August 2011, Washington DC (US) http://www.icpweb.org Archived 2012-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Ketty, una trans capeggiava gli Scissionisti". corrieredelmezzogiorno.corriere.it.

- ^ a b Zito, Eugenio (August 2013). "Disciplinary crossings and methodological contaminations in gender research: A psycho-anthropological survey on Neapolitan femminielli". International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches. 7 (2): 204–217. doi:10.5172/mra.2013.7.2.204. ISSN 1834-0806.

- ^ "Arrestata Ketty, transessuale e boss a Scampia » Panorama.it - Italia". Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ^ a b "I femminielli (Achille della Ragione)". www.guidecampania.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Raven Kaldera. Hermaphrodeities: The Transgender Spirituality Workbook. Hubbardston, Massachusetts: Asphodel Press, 2008. P. 174-179.

- ^ a b Kirsten Cronn-Mills, Transgender Lives: Complex Stories, Complex Voices (2014, ISBN 0761390227), page 39

- ^ a b Teresa Hornsby, Deryn Guest, Transgender, Intersex and Biblical Interpretation (2016, ISBN 0884141551), page 47

- ^ Laura Anne Seabrook, "About this comic." Tales of the Gallae. http://totg-mirror.thecomicseries.com/about/

- ^ Maarten J. Vermaseren, Cybele and Attis: the myth and the cult, translated by A. M. H. Lemmers, London: Thames and Hudson, 1977, p.85, referencing Ovid, Fasti IV.9

- ^ Maarten J. Vermaseren, Cybele and Attis: the myth and the cult, translated by A. M. H. Lemmers, London: Thames and Hudson, 1977, p.97.

- ^ "Pasquetta con i femminielli nel quadrilatero Carceri". lostrillone.tv. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ "Il Santuario di Montevergine e la Candelora". Archived from the original on 2012-01-27.

- ^ "Traditional Dances - The Tummurriata". liceoumberto.eu. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Tombolata dei Femminielli: divertimento e tradizione ad Avellino". irpinianews.it. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "The Songs of LA GATTA CENERENTOLA - Roberto de Simone - Universitas adversitatis - Organiser Ed Emery". www.thefreeuniversity.net. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

References

[edit]- Carrano, Gennaro and Simonelli, Pino, Un mariage dans la baie de Naples; Naples ville travestie; special issue Mediterranée, "Masques", été 1983 (numéro 18), pp. 106–116.

- Dall'Orto, Giovanni, Ricchioni, femmenelle e zamel: l'"omosessualità mediterranea".

- De Blasio, Abele; (1897); ‘O spusarizio masculino (il matrimonio fra due uomini), in: Usi e costumi dei camorristi; Gambella, Naples. Reprint: Edizioni del Delfino, Naples 1975, pp. 153–158.

- della Ragione A. I Femminielli. On-line at Guide Campania. (retrieved: Nov. 12, 2009)

- Malaparte, Curzio. La Pelle. Vallechi editore. Florence. 1961

- Eugenio Zito, Paolo Valerio, Corpi sull'uscio, identità possibili. Il fenomeno dei femminielli a Napoli, Filema, 2010

- Zito, Eugenio. "Disciplinary crossings and methodological contaminations in gender research: a psycho-anthropological survey on Neapolitan femminielli." International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, vol. 7, no. 2, 2013, p. 204+. Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com.uaccess.univie.ac.at/apps/doc/A354578053/AONE?u=43wien&sid=AONE&xid=103bdda0. Accessed 23 Oct. 2018.

External links

[edit]- Mythology of femminielli in Naples (in Italian)

- The femminielli, from the book "Le ragioni di della Ragione" (in Italian)

- The world of the "femminiello", culture and tradition (in Italian)

- Peppe Barra – Il Matrimonio di Vincenzella – theatre performance.