Annie Kenney

Annie Kenney | |

|---|---|

Kenney in 1909 | |

| Born | Ann Kenney 13 September 1879 Springhead, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 9 July 1953 (aged 73) Hitchin, Hertfordshire, England |

| Occupation(s) | Political activism and trade unionism |

| Known for | Political activist and suffragette for the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) |

| Spouse | James Taylor |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Sarah (Nell), Jessie, Jenny and Kitty (sisters) |

Ann "Annie" Kenney (13 September 1879 – 9 July 1953) was an English working-class suffragette and socialist feminist[1] who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union. She co-founded its first branch in London with Minnie Baldock.[2] Kenney attracted the attention of the press and public in 1905 when she and Christabel Pankhurst were imprisoned for several days for assault and obstruction related to the questioning of Sir Edward Grey at a Liberal rally in Manchester on the issue of votes for women. The incident is credited with inaugurating a new phase in the struggle for women's suffrage in the UK with the adoption of militant tactics. Annie had friendships with Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence, Mary Blathwayt, Clara Codd, Adela Pankhurst, and Christabel Pankhurst.

Early life

[edit]Kenney was born in 1879 in Springhead, West Riding of Yorkshire, to Horatio Nelson Kenney (1849–1912) and Anne Wood (1852–1905).[3] She was the fourth daughter in a family of twelve children, eleven of whom survived infancy.[4] There were six other sisters: Sarah (Nell), Alice, Caroline (Kitty), Jane (Jenny), and Jessie. Their parents encouraged reading, debating, and socialism. Three of the sisters became teachers, and a brother became a businessman. A brother, Rowland Kenney, became the first editor (in 1912) of the Daily Herald.[3]

Annie started part-time work in a cotton mill at the age of 10, while also attending school. She began full-time work at 13,[3] which involved 12-hour shifts from six in the morning. Employed as a weaver's assistant, or "tenter", part of her job was to fit the bobbins and attend to the strands of thread when they broke; during one such operation, one of her fingers was ripped off by a spinning bobbin. She remained at the mill for 15 years, was involved in trade-union activities, furthered her education through self-study and—inspired by Robert Blatchford's publication, The Clarion—promoted the study of literature among her colleagues. She was a regular church attender[5][6][7] and sang in a local choir.[3]

When her mother died in 1905, Kenney and six siblings remained with her father at 71 Redgrave Street, Oldham.[3]

Activism

[edit]Kenney became actively involved in the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) after the premature death of her mother Ann at the age of fifty-three in January 1905,[3] when she and her sister Jessie heard Teresa Billington-Greig and Christabel Pankhurst[8] speak at the Oldham socialist Clarion Vocal Club in 1905.[7] Kenney described Billington's message delivered as 'a sledgehammer of cold logic and reason' but that she liked Christabel, and was invited to meet her mother (Emmeline Pankhurst) a week later, anticipating this made Kenney feel that she 'lived on air;.. simply could not eat... instinctively felt a great change had come'. This resulted in weekly visits on her half-day off to be trained in public speaking and to collect leaflets on women's suffrage. Kenney and her sister Jessie handed these out to women working in the mills in Oldham. Kenney found herself explaining labour rights, unemployment and for giving women the right to vote, to a large Manchester crowd.[3]

During a Liberal rally at the Free Trade Hall, Manchester, in October 1905, Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a political meeting attended by Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey to shout: "Will the Liberal government give votes to women?" After unfurling a banner declaring "Votes for Women" and shouting, they were thrown out of the meeting and arrested for causing an obstruction; Pankhurst was taken into custody for a technical assault on a police officer after she spat at him to provoke an arrest (although she wrote later that it was a dry spit, more of a "pout").[9] Kenney was imprisoned for three days for her part in the protest; she was jailed 13 times in total.

Emmeline Pankhurst wrote in her autobiography that "this was the beginning of a campaign the like of which was never known in England, or for that matter in any other country... we interrupted a great many meetings... and we were violently thrown out and insulted. Often we were painfully bruised and hurt..."

Kenney and Minnie Baldock formed the first London branch of the WSPU in Canning Town in 1906, holding meetings at Canning Town Public Hall.[10] In June that year Kenney, Adelaide Knight, and Mrs Sbarborough were arrested when they tried to obtain an audience with H. H. Asquith, then Chancellor of the Exchequer.[11][12] Offered the choice of six weeks in prison or giving up campaigning for one year, Kenney chose prison, as did the others.[11] Kenney was invited to speak to working women's gatherings across the country throughout the campaign, including campaigning for a week in Liverpool at street meetings organised by Patricia Woodlock and Alice Morrissey.[13] In February 1907, she was in Aberdeen where she was supposed to be accompanying Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, but they had been arrested at the House of Commons protest. Kenny joined Helen Fraser at the city's Castlegate, describing it as a 'special duty' allocated her by the national WSPU.[14]

Kenney became part of the senior hierarchy of the WSPU, organising the 1911 census boycott in Bristol[15] and becoming the WSPU deputy in 1912. In 1913 she and Flora Drummond arranged for WSPU representatives to speak with leading politicians David Lloyd George and Sir Edward Grey. The meeting had been arranged with the proviso that these were working-class women representing their class. They explained the terrible pay and working conditions that they suffered and the hope that a vote would enable women to challenge the status quo in a democratic manner. Alice Hawkins from Leicester explained how her fellow male workers could choose a man to represent them while the women were left unrepresented.[16]

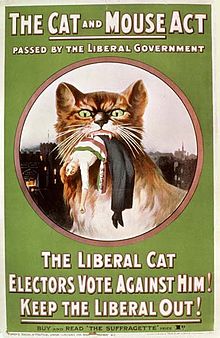

Kenney, who was involved in other militant acts and underwent force-feeding many times, was always determined to confront the authorities and highlight the injustice of the Cat and Mouse Act: a suffragette nickname for the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 which allowed prisoners who were ill (especially from hunger strike or force feeding), to be released on licence for a period, until well enough to be returned to prison to complete their sentence. Supporters, including Agnes Harben and her husband, would offer Kenney and others to recuperate at their country house, Newlands, Chalfont St. Peter.[9] On one occasion in January 1914 when she had just been released from prison and was very weak, The Times reported that at a meeting in Knightsbridge Town Hall chaired by Norah Dacre Fox, the WSPU general secretary:

Miss Kenney was conveyed to the meeting in a horse ambulance; and she was borne into the meeting on a stretcher, which was raised to the platform and placed on two chairs. She raised her right hand and fluttered a handkerchief and, covered with blankets, lay motionless watching the audience. Later, her licence under the "Cat and Mouse" Act was offered for sale. Mrs Dacre Fox stated that an offer of £15 had already been received for it, and the next was one of £20, then £25 was bid, and at this price it was sold. Soon afterwards Miss Kenney was taken back to the ambulance. Detectives were present, but no attempt was made to rearrest Miss Kenney, whose licence had expired.[17]

Kenney had been given a Hunger Strike Medal 'for Valour' by WSPU.[citation needed]

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Emmeline Pankhurst called an end to suffragette militancy and urged the women to become actively involved in war work by taking on jobs that had traditionally been regarded as in the male preserve,[18] as most of those men were now absent at the front. This was set in train through the pages of The Suffragette, relaunched on 16 April 1915 with the slogan that it was 'a thousand times more the duty of the militant Suffragettes to fight the Kaiser for the sake of liberty than it was to fight anti-Suffrage Governments'. In autumn 1915 Kenney accompanied Emmeline Pankhurst, Flora Drummond, Norah Dacre Fox and Grace Roe to South Wales, the Midlands and Clydeside on a recruiting and lecture tour to encourage trade unions to support war work.[19] Kenney took her message as far afield as France and the United States.

In August 1921, Kenney began publishing her 'Revelations' and so-called 'secrets of suffragettes' in a series of twelve articles in the popular weekly Scottish paper, The Sunday Post, among the news, human interest stories and short features. The series began with a potted history of her life as a 'factory girl' (from the age of ten, part-time and from thirteen, full time); how she joined the socialist Clarion choir and thus came to hear Christabel Pankhurst speak and a week later was a guest at the Pankhursts' Manchester home. She goes on to describe how she felt about suddenly speaking in public and to crowds of fellow factory workers and learning to handle the hecklers.[20] In other episodes in the series, Kenney gave dramatic first person accounts of the events (and people she met) during her suffrage activism, including some of those described above.[20] In the final article in November that year, her last story described meeting the Archbishop of Canterbury (Randall Davidson) in Lambeth Palace in 1914, claiming 'sanctuary' until women were given the vote (which he recognised could be years); she elaborates on the various attempts to make her leave, her arrest, going on a 7-day hunger strike, her release to recover and her return to sit on the doorstep, only to be taken off in an ambulance to the workhouse infirmary.[21]

Personal life

[edit]Annie had many close friendships with women in the Suffragette Movement. Christabel Pankhurst and Kenney were allegedly lovers.[22] The two went on holiday to Sark together and some sources suggest the relationship was platonic rather than romantic.[23] Kenney was a family friend of the Blathwayts. She was a frequent visitor to their home, Eagle House, and unlike everyone else she planted four trees. The Blathwayts paid for presents and watches, and paid medical and dentistry bills for her and her sisters.[23] Mary Blathwayt made notes in her diary of the women Kenney slept with when she stayed at Eagle House. Blathwayt's romantic jealousy has been proposed as a reason. She noted ten alleged short-lived lovers.[22] According to Mary, she shared beds with herself, Clara Codd and Adela Pankhurst.[citation needed]

After women over age 30 won the vote in 1918 Kenney married James Taylor (1893–1977) and settled in Letchworth, Hertfordshire. A son, Warwick Kenney Taylor, was born in 1921. After a stroke[24] she died on 9 July 1953, aged 73, in Lister Hospital, Hitchin.[25]

Her funeral was conducted according to the rites of AMORC and her ashes were scattered by her family on Saddleworth Moor.[26]

Posthumous recognition

[edit]In 1999, Oldham Council erected a blue plaque in her honour at Lees Brook Mill in Lees, near Oldham, where Kenney had started work in 1892.[27] On 14 December 2018 a statue, funded by public subscription, was unveiled in front of the Old Town Hall in Oldham.[28]

Her name and image (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are etched on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, that was unveiled in 2018.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Linehan, Thomas (2012). Modernism and British Socialism. Springer. p. 39.

- ^ Jackson, Sarah (12 October 2015). "The suffragettes weren't just white, middle-class women throwing stones". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 20–23. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- ^ Woodhead, Geoffrey (2003). The Kenney family of Springhead. Working Class Movement Library, Salford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Helen Rappaport. Encyclopedia of women social reformers, Volume 1 (ABC-CLIO, 2001) p. 359-361

- ^ E. S. Pankhurst. The suffragette: the history of the women's militant suffrage movement, 1905–1910 (New York Sturgis & Walton Company, 1911) p. 19ff.

- ^ a b Annie Kenney, Marie M. Roberts, Tamae Mizuta. A Militant (Routledge, 1994) Intro.

- ^ "Jessie Kenney". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b Crawford, Elizabeth (2003) [1999]. The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. Routledge. pp. 269, 489. ISBN 9780415239264.

- ^ Jackson, Sarah (12 October 2015). "The suffragettes weren't just white, middle-class women throwing stones". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Adelaide Knight, leader of the first east London suffragettes". East End Women's Museum. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Rosemary Taylor (4 August 2014). East London Suffragettes. History Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-7509-6216-2.

- ^ Cowman, Krista (November 1994). "Engendering Citizenship The Political Involvement of Women on Merseyside 1890 -1920" (PDF). University of York Centre for Women's Studies. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Pedersen, Sarah. "The Aberdeen Women's Suffrage Campaign". suffrageaberdeen.co.uk. copyright WildFireOne. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Liddington, Jill (1 January 2014). "Annie Kenney's Bristol and Mary Blathwayt's Bath". Vanishing for the vote: Suffrage, citizenship and the battle for the census. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-84779-888-6.

- ^ "Let's not forget the working class suffragettes". www.newstatesman.com. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Miss Kenney's Health – Released Suffragist at a Meeting" The Times, 21 October 1913, p. 5)

- ^ parliament.uk

- ^ McPherson, Angela; McPherson, Susan (2011). Mosley's Old Suffragette – A Biography of Norah Elam. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b Kenney, Annie (28 August 1921). "Starts today Great New Exclusive Series - The Revelations of Annie Kenney - Secrets of Suffragettes Told by Famous Leader". The Sunday Post. No. 4 Sept 1921 p.6-7, 11 Sept 1921 p.6-7, 18 Sept 1921 p.6-7, 25 Sept 1921 p.6, 2 Oct 1921 p.6, 9 Oct 1921 p.6, 16 Oct 1921 p.6, 23 Oct 1921 p.7, 30 Oct 1921 p.7, 6 Nov 1921 p.7. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Kenney, Annie (13 November 1921). "The last Phase of the Women's Fight - My Interview with the Archbishop - A Memorable Visit to Lambeth Palace". The Sunday Post. p. 7.

- ^ a b Thorpe, Vanessa; Marsh, Alec (11 June 2000). "Diary reveals lesbian love trysts of suffragette leaders". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ a b Martin Pugh (31 December 2013). The Pankhursts: The History of One Radical Family. Random House. pp. 209–213. ISBN 978-1-4481-6268-0.

- ^ "The British Archive for Contemporary Writing CollectionsOnline | KP/AK/6/3 - Scattering of Annie Kenney's ashes -photographs". Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Annie Kenney - a truly remarkable Oldham woman". Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Scattering of Annie Kenney's ashes on the Yorkshire moors, 1953". SuffragetteStories.omeka.net. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "oldham.gov.uk". Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Emotions run high as 'beautiful' Annie Kenney statue is unveiled". Oldham Chronicle. 14 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Drinkwater, Carol (2015). My Story: Suffragette. Scholastic. ISBN 978-1-407-15652-1.

- Kenney, Annie (1924). Memories of a Militant. E. Arnold & Company. ISBN 978-9-333-49205-8.

- Marlow, Joyce (2013). Suffragettes: The Fight for Votes for Women. Virago. ISBN 978-0-349-00775-5.

- Meeres, Frank (2013). Suffragettes: How Britain's Women Fought & Died for the Right to Vote. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-60007-9.

External links

[edit]- The Kenney Papers (University of East Anglia)

- Suffragette Stories (University of East Anglia)

- Portraits of Annie Kenney at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Suffragette photographs

- Spartacus Schoolnet

- Manchester Guardian reports the 1905 court case