Russia under Vladimir Putin

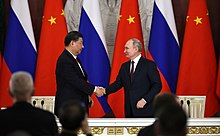

Putin in 2024 | |

| Presidencies of Vladimir Putin | |

| Party | CPSU (1975–1991) Our Home – Russia (1995–1999) Unity (1999–2001) United Russia (2008–2012) Independent (1991–1995; 2001–2008, 2012–present) |

|---|---|

| Seat | Moscow Kremlin |

First term 7 May 2000 – 7 May 2008 (acting: 31 December 1999 – 7 May 2000) | |

| Election | |

Second term 7 May 2012 – present | |

| Election | |

|

| |

| Official website | |

Since 1999, Vladimir Putin has continuously served as either president (acting president from 1999 to 2000; 2000–2004, 2004–2008, 2012–2018, 2018–2024 and 2024 to present) or Prime Minister of Russia (three months in 1999, full term 2008–2012).[1]

During his presidency, he has been a member of the Unity party and the United Russia party. He is also affiliated with the People's Front, a group of supporters that Putin organized in 2011 to help improve the public's perception of United Russia.[2] His political ideology, priorities and policies are sometimes referred to as Putinism.

Putin has enjoyed high domestic approval ratings[disputed – discuss] throughout the majority of his presidency, with the exception of 2011–2013 which is likely due to the 2011–2013 Russian protests.[3][4][5] In 2007, he was Time magazine's Person of the Year.[6] In 2015, he was designated No. 1 in Time 100, Time magazine's list of the top 100 most influential people in the world.[7] From 2013 to 2016, he was designated No. 1 on the Forbes list of The World's Most Powerful People.[8] The Russian economy and standard of living grew rapidly during the early period of Putin's regime, fueled largely by a boom in the oil industry.[9][10][11] However, lower oil prices and sanctions for Russia's annexation of Crimea led to recession and stagnation in 2015 that has persisted into the present day.[12] Political freedoms have been sharply curtailed,[13][14][15] leading to widespread condemnation from human rights groups,[16][17][18][19] as well as Putin being described as a dictator since 2022.[20][21][22]

Overview

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Part of the Politics series |

| Populism |

|---|

|

|

The political system under Putin has been described as incorporating some elements of economic liberalism, a lack of transparency in governance, cronyism, nepotism and pervasive corruption.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Between 1999 and 2008, the Russian economy grew at a steady pace,[29] which some experts attribute to the sharp rouble devaluation of 1998, Boris Yeltsin-era structural reforms, rising oil prices and cheap credit from Western banks.[30][31][32] In former ambassador Michael McFaul's opinion (June 2004), Russia's "impressive" short-term economic growth "came simultaneously with the destruction of free media, threats to civil society and an unmitigated corruption of justice".[33]

During Putin's first two terms as president, he signed into law a series of liberal economic reforms, such as the flat income tax of 13 percent, reduced profits-tax and new land and civil codes.[33] Within this period, poverty in Russia reduced by more than half[34] and real GDP has grown rapidly.[35]

In foreign affairs, the Putin government seeks to emulate the former Soviet Union's grandeur, belligerence and expansionism.[36][37] In November 2007, Simon Tisdall of The Guardian pointed out that "just as Russia once exported Marxist revolution, it may now be creating an international market for Putinism" as "more often than not, instinctively undemocratic, oligarchic and corrupt national elites find that an appearance of democracy, with parliamentary trappings and a pretense of pluralism, is much more attractive, and manageable, than the real thing".[38]

In an article published on 20 September 2007 in The Washington Times, American economist Richard W. Rahn called Putinism "a Russian nationalistic authoritarian form of government that pretends to be a free market democracy" and which "owes more of its lineage to fascism than communism", noting that "Putinism depended on the Russian economy growing rapidly enough that most people had rising standards of living and, in exchange, were willing to put up with the existing soft repression".[39] He predicted that "as Russia's economic fortunes changed, Putinism was likely to become more repressive".[39] After Rahn's remarks, Putin took actions to lessen democracy, promote conservative beliefs and values, and silence opposition to his policies and administration.[40]

Russian historian Andranik Migranyan saw the Putin regime as restoring what he viewed as the natural functions of a government after the period of the 1990s, when oligopolies expressing only their own narrow interests allegedly ruled Russia. Migranyan said: "If democracy is the rule by a majority and the protection of the rights and opportunities of a minority, the current political regime can be described as democratic, at least formally. A multiparty political system exists in Russia, while several parties, most of them representing the opposition, have seats in the State Duma".[41]

Putinism

In an article published 11 January 2000 in Sovetskaya Rossiya, Russian political analyst Andrey Piontkovsky characterized Putinism as the highest and final stage of bandit capitalism in Russia, the stage where, as Vladimir Lenin said, the bourgeoisie throws the flag of democratic freedoms and human rights overboard; and also as a war, "consolidation" of the nation on the grounds of hatred against some ethnic group, attack on freedom of speech, information brainwashing, isolation from the outside world, and further economic degradation.[42] It was the first recorded usage of the term "Putinism".[43]

The terms "Putinism" and "Putinist" often have negative connotations when used in Western media[44][45][46][47][48][49] to reference the Russian government under Putin where siloviki, the military-security establishment, allegedly control much of the political and financial power. Many siloviki[50][51] are Putin's personal friends or previously worked with him in state security and intelligence agencies, such as the FSB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the military.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58]

Cassiday and Johnson argue that since taking power in 1999, "Putin has inspired expressions of adulation the likes of which Russia has not seen since the days of Joseph Stalin. Tributes to his achievements and personal attributes have flooded every possible media".[59] Ross says the cult emerged quickly by 2002 and emphasizes Putin's "iron will, health, youth and decisiveness, tempered by popular support". Ross concludes: "The development of a Putin mini cult of personality was based on a formidable personality at its heart".[60]

Acting president (1999–2000)

Putin's first campaign program

On 31 December 1999, President Boris Yeltsin resigned. Under the Constitution of Russia, the then Prime Minister of Russia Vladimir Putin became acting president.[61]

The day before, a program article signed by Putin, "Russia at the turn of the millennium", was published on the government web site. The potential head of state expressed his views on the past and problems of the country.[62] The first task in Putin's view was consolidation of Russia's society: "The fruitful and creative work, which our country needs so badly, is impossible in a divided and internally atomised society".[63] However, the author stressed: "There should be no forced civil accord in a democratic Russia. Social accord can only be voluntary".[63]

The author stressed the importance of strengthening the state: "The key to Russia's recovery and growth today lies in the state-political sphere. Russia needs strong state power and must have it". Detailing his view, Putin emphasized: "Strong state power in Russia is a democratic, law-based, workable federal state".[63]

Regarding the economic problems, Putin pointed out the need to significantly improve economic efficiency, the need to carry out a coherent and result-based social policy aimed at battling poverty, and the need to provide stable growth for people's well-being.[63]

The article stated the importance of government support of science, education, culture, and health care since "[a] country in which the people are not healthy physically and psychologically, are poorly educated and illiterate, will never rise to the peaks of world civilisation".[63]

The article concluded with an alarmist statement that Russia was in the midst of one of the most difficult periods in its history: "For the first time in the past 200–300 years, it is facing the real threat of slipping down to the second, and possibly even third, rank of world states".[63] To avoid that, he argued that there was a need for tremendous effort by all the intellectual, physical and moral forces of the nation because "[e]verything depends on us, and us alone, on our ability to recognise the scale of the threat, to unite and apply ourselves to lengthy and hard work".[63]

As stated in the history course by Russian Doctors of History Barsenkov and Vdovin, the basic ideas of the article were represented in the election platform of Vladimir Putin and supported by the majority of the country's citizens, leading to the victory of Vladimir Putin in the first round of the 2000 election, with 52 per cent of the votes cast.[64]

First presidential term (2000–2004)

The outline of Russia's foreign policy was presented by Vladimir Putin in his Address to Russia's Federal Assembly in April 2002: "We are building constructive, normal relations with all the world's nations—I want to emphasise, with all the world's nations. However, I want to note something else: the norm in the international community, in the world today, is also harsh competition—for markets, for investment, for political and economic influence. And in this fight, Russia needs to be strong and competitive". "I want to stress that Russian foreign policy will in the future be organized in a strictly pragmatic way, based on our capabilities and national interests: military and strategic, economic and political. And also taking into account the interests of our partners, above all in the CIS".[65]

In his 2008 book, the Russian political commentator, retired KGB lieutenant-general Nikolai Leonov, noted that Putin's program article was barely noticed then and never revisited later—a fact that Leonov regretted, because "its content is most important for contrasting against his [Putin's] subsequent actions" and thus figuring out Putin's pattern, under which "words, more often than not, do not match his actions".[66]

Restoring functionality of government

The concept of "Putinism" was described in a positive sense by Russian political scientist Andranik Migranyan.[41] According to Migranyan, Putin came into office when the worst regime was established: the economy was "totally decentralized" and "the state had lost central authority while the oligarchs robbed the country and controlled its power institutions". In two years, Putin restored the hierarchy of power, ending the omnipotence of regional elites as well as destroying political influence of "oligarchs and oligopolies in the federal center". The Boris Yeltsin-era non-institutional center of power commonly called "The Family" was ruined, which according to Migranyan in turn undercut the positions of the actors such as Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gusinsky, who had sought to privatize the Russian state "with all of its resources and institutions".[41]

Migranyan said that Putin began establishing common rules of the game for all actors, starting with an attempt to restore the role of the government as the institution expressing the combined interests of the citizens and "capable of controlling the state's financial, administrative and media resources". According to Migranyan: "Naturally, in line with Russian traditions, any attempt to increase the state's role causes an intense repulsion on the part of the liberal intellectuals, not to mention a segment of the business community that is not interested in the strengthening of state power until all of the most attractive state property has been seized". Migranyan claimed that oligopolies' view of democracy was set on a premise of whether they were close to the center of power, rather than "objective characteristics and estimates of the situation in the country". Migranyan said "free" media, owned by e.g. Berezovsky and Gusinsky, were nothing similar to free media as understood by the West, but served their own economic and political interests while "all other politicians and analysts were denied the right to go on the air".[41]

Migranyan sees enhancement of the role of the law enforcement agencies as a trial to set barriers against criminals, "particularly those in big business".[41]

Migranyan sees in 2004 fruition of the social revolution initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, whose aims were to rebuild the social system, saying that "the absolute dominance of private ownership in Russia, recognized by all political forces today, has been the greatest achievement and result of this social revolution".[41]

According to Migranyan, the major trouble of Russian democracy is the inability of its civil society to rule the state, and underdevelopment of public interests. He sees that as the consequence of the Yeltsin era's family-ruled state being unable to pursue "a favorable environment for mid-sized and small businesses". Migranyan sees modern Russia as a democracy, at least formally, while "the state, having restored its effectiveness and control over its own resources, has become the largest corporation responsible for establishing the rules of the game". Migranyan wonders how much this influence might extend into the future. In 2004, he saw two possibilities for the Putin regime: either transformation into a consolidated democracy, or bureaucratic authoritarianism. However, "if Russia is lagging behind the developed capitalist nations in regard to the consolidation of democracy, it is not the quality of democracy, but rather its amount and the balance between civil society and the state".[41]

Second presidential term (2004–2008)

The report by Andrew C. Kuchins in November 2007 said that "Russia today is a hybrid regime that might best be termed "illiberal internationalism", although neither word is fully accurate and requires considerable qualification. From being a weakly institutionalized, fragile, and in many ways distorted proto-democracy in the 1990s, Russia under Vladimir Putin has moved back in the direction of a highly centralized authoritarianism, which has characterized the state for most of its 1,000-year history. But it is an authoritarian state where the consent of the governed is essential. Given the experience of the 1990s and the Kremlin's propaganda emphasizing this period as one of chaos, economic collapse, and international humiliation, the Russian people have no great enthusiasm for democracy and remain politically apathetic in light of the extraordinary economic recovery and improvement in lifestyles for so many over the last eight years. The emergent, highly centralized government, combined with a weak and submissive society, is the hallmark of traditional Russian paternalism".[67]

In a 2007 interview with Der Spiegel, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn commented on the Putin regime: "Putin has inherited a plundered and downtrodden country with a majority of her people demoralized and poor. He understood and managed what was possible — a gradual, slow recovery. These efforts were neither noticed nor appreciated immediately. In any case, one is hard pressed to find examples in history when measures by one country for recovering strength of its own government is met favorably by other governments".[68]

According to a 2007 article by Dimitri Simes, published in Foreign Affairs: "With high energy prices, sound fiscal policies, and tamed oligarchs, the Putin regime no longer needs international loans or economic assistance and has no trouble attracting major foreign investment despite growing tension with Western governments. Within Russia, relative stability, prosperity, and a new sense of dignity have tempered popular disillusionment with growing state control and the heavy-handed manipulation of the political process".[69]

BBC diplomatic correspondent Bridget Kendall in her 2007 article described Russia's "scarred decade" of the 1990s, with "rampant hyperinflation", harsh Yeltsin policies, population decrease at a rate similar to that for a nation at war, and the country turning "from superpower into beggar", and then wonders: "So who can blame Russians for welcoming the relative stability Putin has presided over during the past seven years, even if other aspects of his rule have cast an authoritarian shadow? In the back-to-front world of Russian politics, it is not too little democracy that many people fear, but too much of it. This, I discovered, is why some are calling for Putin to stay on for a third term. Not because they admire him—privately, many say that he and his cronies are just as corrupt and disdainful of others as their communist predecessors were—but because they mistrust the idea of democracy, resent the West for pushing it, and fear what might happen as a result of next year's elections. Recent experience has taught them that change is usually for the worse and best avoided".[70]

Sociological data

According to Dr. Mark Smith (March 2003), some of the main features of Putin's regime to that point were the development of a corporatist system by pursuing close ties with business organizations, social stability and co-optation of opposition parties.[71] He determined three main groupings in Putin's early leadership: 1) the siloviki, 2) economic liberals and 3) supporters of "the Family", i.e. those who were close to Yeltsin.[71]

Olga Kryshtanovskaya, who carried out a sociological survey in 2004, put the relative number of siloviki in the Russian political elite at 25%.[50] In Putin's "inner circle" which constitutes about 20 people, the percentage of siloviki rises to 58% and fades to 18–20% in parliament and 34% in the government overall.[50] According to Kryshtanovskaya, there was no capture of power as Kremlin bureaucracy has called siloviks in order to "restore order". The process of siloviki coming into power allegedly started in 1996, during Boris Yeltsin's second term. "Not personally Yeltsin, but the whole elite wished to stop the revolutionary process and consolidate the power". When silovik Putin was appointed prime minister in 1999, the process was boosted. According to Olga: "Yes, Putin has brought siloviks with him. But that's not enough to understand the situation. Here's also an objective aspect: the whole political class wished them to come. They were called for service... There was a need of a strong arm, capable from point of view of the elite to establish order in the country".[50]

Kryshtanovskaya noted that there were also people who had worked in structures believed to be affiliated with the KGB/FSB, such as the Soviet Union Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Governmental Communications Commission, Ministry of Foreign Trade, Press Agency News and others. The work per se in such agencies would not necessarily involve contacts with security services, but would make it likely.[72] Summing up the numbers of official and affiliated siloviki, she came up with an estimate of 77% of such in power.[50]

According to a Russian Public Opinion Foundation 2005 investigation, 34% of respondents think "there is a lack of democracy in Russia because democratic rights and freedoms are not observed", and they also pointed to the lack of law and order. At the same time, 21% of respondents said there was too much democracy in Russia, and many of them pointed to the same drawbacks as the previous group: "[T]he lack of law and order, irresponsibility and non-accountability of politicians". According to the Foundation: "As we can see, Russians' negative opinions about democracy are based on their dissatisfaction with contemporary conditions, while some respondents think the democratic model is not suitable in principle". Considering the modern regime: "It is interesting that most respondents think Putin's government marks the most democratic epoch in Russian history (29%), while second place goes to Brezhnev's times (14%). Some people mentioned Gorbachev and Yeltsin in this context (11% and 9%, respectively)".[73]

At the end of 2008, Lev Gudkov, based on the Levada Center polling data, pointed out the near-disappearance of public opinion as a socio-political institution in Putin's Russia and its replacement with the still-efficacious state propaganda.[74]

Prime minister (2008–2012)

The 2008 power-switching operation between Putin and Medvedev was widely seen as a pro forma action after the constitution did not allow Putin to be reelected for a third term in the 2008 presidential election.[citation needed]

Third presidential term (2012–2018)

According to a study by Olesya Zakharova, researcher in a Research Link between the Higher School of Economics and the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen, after the 2011–2013 protests on Bolotnaya Square, which were described in Russian official discourse as an abuse of democratic freedoms and serious threats to the safety of Russian citizens, Putin presented a new concept of "Russian democracy", which he interpreted exclusively as "compliance with and respect for laws, rules and regulations", and that individual freedoms and human rights were no longer seen as prerequisites for a democratic society.[75]

Russian laws were changed according to this new concept of "democracy". According to a study carried out by the International Federation for Human Rights, about 50 antidemocratic laws were adopted in Russia during the period 2012–2018.[76] The new laws and regulations range from increased surveillance and censorship powers, to laws banning "questioning the integrity of the Russian nation" – effectively banning criticism of Russia's presence in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea – broad laws on "extremism" that grant authorities powers to crack down on political and religious freedom, to imposing certain views on Russian history by forbidding people to think differently. A specific and complex branch of laws has also been constructed through these last years to make it more difficult for NGOs and human rights organisations to run and communicate on their activities, to access information, and to receive international funding, thus severely hindering their ability to operate independently, and for the smaller ones, to survive.[77]

Fight against modern socio-political thinking and activity

On 21 November 2012, the Federal Law of 20 July 2012 No.121-FZ "On Amendments to Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation regarding the Regulation of the Activities of Non-profit Organisations Performing the Functions of a Foreign Agent",[78] which is the amendments to the Federal Law of 19 May 1995 No.82-FZ "On public associations", the Federal Law of 12 January 1996 No.7-FZ "On Non-profit Organizations", the Federal Law of 7 August 2001 No.115-FZ "On countering the legalization (laundering) of the proceeds of crime and the financing of terrorism", the Criminal Code of Russia and the Criminal Procedure Code of Russia, entered into force.[79] In accordance to this law, Russian non-profit organization, except for state and municipal companies, can be declared foreign agent if it participates in political activity in Russia and receives funding from foreign sources. Political activity is defined as any influence to public opinion and public policy including a sending a requests and petitions. The foreign agent label increases registration barriers for a non-profit organization in Russia. Once registered, non-profit organizations are subject to additional audits and are obliged to mark all their official statements with a disclosure that it is being given by a "foreign agent". This includes restrictions on foreigners and stateless peoples from establishing or even participating in the organization. Supervisory powers are allowed to intervene and interrupt the internal affairs of the NGO with suspensions for up to six months.

On 1 January 2013, the Federal Law of 28 December 2012 No.272-FZ "On Sanctions for Individuals Violating Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms of the Citizens of the Russian Federation"[80] (also known as Dima Yakovlev Law or Law of Scoundrels) entered into force.[81] It creates a list of citizens who are banned from entering Russia, and also allows the government to freeze their assets and investments. The law suspends the activity of politically active non-profit organizations which receive money from American citizens or organizations. It also bans citizens of the United States from adopting children from Russia. This law was adopted as the answer to American Magnitsky Act.

On 3 June 2015, the amendments to the Federal Law of 28 December 2012 No.272-FZ "On Sanctions for Individuals Violating Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms of the Citizens of the Russian Federation", contained in the Federal Law of 23 May 2015, No.129-FZ "On amendments of some legislative acts of the Russian Federation",[82] entered into force.[83] These amendments give Prosecutor-General of Russia the power to extrajudicially declare foreign and international organizations "undesirable" in Russia and shut them down. There is no procedure for appeals. Organizations that do not disband when given notice to do so, as well as Russians who maintain ties to them, are subject to high fines and significant jail time. The law provides only one ground for recognizing organization as "undesirable" – "a threat to the fundamental principles of the constitutional order of the Russian Federation, defence capability of country or state security".

On 13 June 2016, the opinion of the Venice Commission on Russian undesirable organizations law[84] was published. According to the Venice Commission conclusion, Russian undesirable organizations law consists the vague definition of certain fundamental concepts, such as "non-governmental organisations", grounds on the basis of which the activities of a foreign or international NGO may be declared undesirable, "directing of" and "participating in" the activities of a listed NGO, coupled with the wide discretion granted to the Office of the Public Prosecutor and the lack of specific judicial guarantees in the Federal Law, contradicts the principle of legality. The automatic legal consequences (blanket prohibitions) imposed upon NGOs whose activities are declared undesirable (prohibition to organise and conduct mass actions and public events or to distribute information materials) may only be acceptable in extreme cases of NGOs constituting serious threat to the security of the state or to fundamental democratic principles. In other instances, the blanket application of these sanctions might contradict the requirement under the European Convention on Human Rights that the interference with the freedom of association and assembly has to respond to a pressing social need and has to be proportional to the legitimate aim pursued. Furthermore, the inclusion of an NGO in the List should be made on the basis of clear and detailed criteria following a judicial decision or at least, the decision should be subject to an appropriate judicial appeal.

On 25 November 2017, the amendments, contained in the Federal Law of 25 November 2017 No.327-FZ "On Amendments to the articles 10.4 and 15.3 of the Federal Law "On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection" and to the article 6 of the Russian Federation Law "On the media"",[85] entered into force.[86] In accordance to these amendments, any foreign juridical person distributing printed, audio or audio-visual materials can be declared a foreign media performing the functions of a "foreign agent" even if such juridical person does not have branches or representative offices in Russia. Foreign juridical persons declared a foreign media performing the functions of a "foreign agent" are obliged the Russian foreign agent law.

Fourth presidential term (2018–2024)

On 2 December 2019, the amendments, contained in the Federal Law of 2 December 2019 No.426-FZ "On Amendments to the Russian Federation Law "On the media" and the Federal Law "On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection"",[87] entered into force.[88] In accordance to these amendments, foreign juridical persons declared a foreign media performing the functions of a "foreign agent" must form a Russian juridical person and inform Russian authorities about this. Also these amendments provided the possibility to designate natural person as "foreign agent" – this requires that natural person distributes a materials of a foreign media performing functions of a "foreign agent" (for example, in social media) and receive funding from foreign sources (for example, salary from international company).[89][90]

On 30 December 2020, the amendments, contained in the Federal Law of 30 December 2020 No.481-FZ "On Amendments to Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation regarding the Establishment Additional Measures to Counter the Threats to National Security",[91] entered into force.[92] In accordance to these amendments, special marking are envisaged not only for a publications of non-profit organizations declared a "foreign agent" but also for a publications of its founders, heads, members, employees. Individuals (Russian citizens, foreign citizens and stateless persons) also can be declared "foreign agent" for their political activity. Political activity is defined as any influence to public opinion including publications in social media and public policy including a sending a requests and petitions. The publications of individuals declared "foreign agent" also must be marked. Individuals declared "foreign agent" are obliged to make special reporting and are deprived of the right to hold public office.

The articles 13.15, 19.7.5-2, 19.7.5-3, 19.7.5-4, 19.34, 19.34.1, 20.28 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses establish liability providing for substantial fines for violating Russian foreign agent law. The article 330.1 of the Criminal Code of Russia establish criminal liability providing for imprisonment for up to 5 years and compulsory labour for violating Russian foreign agent law.[93] The article 20.33 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses establish liability providing for substantial fines for violating Russian undesirable organizations law. The article 284.1 of the Criminal Code of Russia establish criminal liability providing for imprisonment for up to 6 years and compulsory labour for violating Russian undesirable organizations law.[94]

2020 constitutional amendments

In January 2020, Putin proposed a number of substantial amendments to the Constitution of Russia. To introduce these amendments, he held a referendum. They were approved on 1 July 2020 by a contested popular vote. The amendments had wide reaching impacts, including extending presidential term limits, allowing the president to fire federal judges, and constitutionally banning same-sex marriage.[95]

With Putin's signing a decree on 3 July 2020 to officially insert the amendments into the Russian Constitution, they took effect on 4 July 2020.[96]

The Venice Commission concluded that the amendments have disproportionately strengthened the position of the president of the Russian Federation and have done away with some of the checks and balances originally foreseen in the Constitution, taken together, these changes go far beyond what is appropriate under the principle of separation of powers, even in presidential regimes, and the speed of the preparation of such wide-ranging amendments was clearly inappropriate for the depth of the amendments considering their societal impact.[97]

Persecution of Navalny and mass protests

Protests in Russia began on 23 January 2021 in support of opposition leader Alexei Navalny who was detained upon his arrival at Sheremetyevo Airport after treatment and rehabilitation in Germany. On the first day, protests were held in 198 towns and cities across Russia. On 31 January, more than 4000 protesters were detained which is the record number in Russia's post-Soviet history.[98]

On 2 February, Navalny's suspended sentence of three and a half years was replaced with a prison sentence. In March, his team launched a campaign demanding for his freedom, with protests planned after 500,000 people pledge to participate. On 21 April 2021, there was another mass protest. Subsequently, Russian authorities identified participants of the protest using public video surveillance and facial recognition system and initiated proceedings against them; many protesters were dismissed from their jobs and were expelled from universities.[99]

On 9 June 2021, Vyacheslav Polyga, judge of Moscow City Court, upheld the administrative claim of the prosecutor of Moscow city Denis Popov and decided[100] to recognize Anti-Corruption Foundation, Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation and Alexei Navalny staff as extremist organizations, to liquidate Anti-Corruption Foundation, Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation and confiscate their assets, to prohibit the activity of Alexei Navalny staff (case No.3а-1573/2021).[101] Case hearing was held in camera because, as indicated by advocate Ilia Novikov, the case file including the text of the administrative claim was classified as state secret.[102] According to advocate Ivan Pavlov, Alexei Navalny was not the party to the proceedings and the judge refused to give him such status; at the hearing, the prosecutor stated that defendants are extremist organizations because they want the change of power in Russia and they promised to help participants of the protest with payment of administrative and criminal fines and with making a complaints to the European Court of Human Rights.[103][104] On 4 August 2021, First Appellate Ordinary Court located in Moscow upheld the decision of the court of first instance (case No.66а-3553/2021) and this decision entered into force that day.[105] On 28 December 2021, it was reported that Anti-Corruption Foundation, Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation and 18 natural persons including Alexei Navalny filed a cassation appeals to the Second Cassation Ordinary Court.[106] On 25 March 2022, the Second Cassation Ordinary Court rejected all cassation appeals and upheld the judgements of lower courts (case No.8а-5101/2022).[107]

Changes in the political and law enforcement practice

In the opinion of Vladimir Pastukhov, political scientist, Russian advocate and honorary senior research associate of University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies, after amendments to the Constitution of Russia, the phase transition had happened – Russia had transformed from authoritarian dictatorship into totalitarian tyranny. This transition is due to the convergence of two factors: the completion of establishment of the repressive infrastructure and the creation of ersatz ideology which is the eclectic set composed of such elements as paternalistic autocracy (tsarism), communism, Pan-Slavism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Eurasianism, right-wing populism, left-wing populism, cult of victory in Great Patriotic War, anti-Americanism, imperialism, xenophobia, Russian messianism, versailles syndrome and revanchism. The transformation into totalitarian state is reflected in the transition from selective repressions against opposition politicians and political activists who struggle for power to mass repressions against dissidents and potentially disloyal citizens who just do not want to support Putin's regime.[108]

The poisoning of Dmitry Bykov, writer, poet and literary critic who criticized Putin's regime,[109] the criminal proceedings against Ivan Pavlov, advocate who defended persons accused of treason and extremism,[110] and Denis Karagodin, philosopher who has been digging into archives to find out the truth about his great-grandfather murder during Stalin's Great Purge,[111] and the pressure against numerous independent journalists became the signs of new times.

On 4 June 2021, the amendments, contained in Federal Law of 4 June 2021, No.157-FZ, entered into force. According to these amendments, any person who was a founder, a head, a member, an employee of the organization recognized as extremist or terrorist or just who donated this organization or expressed support for this organization (in writing or orally) is deprived of the right to stand for election. This legal provision has retroactive effect because it includes the case where a person carried out relevant activity before the organization was recognized as extremist or terrorist, nevertheless, such person is deprived of passive suffrage.[112] Furthermore, under Article 282.2 of the Criminal Code of Russia the participation in the activity of extremist organization carries a sentence of between 2 and 6 years' imprisonment for ordinary participants and between 6 and 10 years' imprisonment for founders and heads of such organization. And reigning approach in Russian law enforcement practice is that the former participant of the organization, recognized as extremist and liquidated by court decision, is considered as a person who continues the activity of such organization in the event he is the participant new organization even if these organizations have different statutes and objectives (many activists were convicted in Putin's Russia precisely in accordance with this approach, for example, the members of group supporting the referendum "For responsible authority!"[113] and the members of organization "People's Militia of Russia"[114]). So, the convergence of aforementioned approach in law enforcement practice and new law establishes the legal framework for subsequent political repressions of people who participated or supported the organizations recognized as extremist and liquidated by court decision even if such people's actions occurred prior to the date of court decision.

In Golos assessment, at least 9 million people have been deprived of the right to stand for election in Russia.[116]

On 6 July 2021, the opinion of the Venice Commission on Russian foreign agent law [1] was published.[117] According to the Venice Commission conclusion, Russian foreign agent law constitutes serious violations of basic human rights, including the freedoms of association and expression, the right to privacy, the right to participate in public affairs, as well as the prohibition of discrimination. The Venice Commission is particularly concerned by the combined effect of the most recent amendments on entities, individuals, the media and civil society more broadly. The combined effect of the recent reforms enables authorities to exercise significant control over the activities and existence of associations as well as over the participation of individuals in civic life.

Education reforms

On 1 June 2021, the Federal Law of 5 April 2021 No.85-FZ "On Amendments to the Federal Law "About education in Russian Federation""[118] entered into force.[119] This law establishes the concept of the outreach activity: it is the activity, carrying out outside educational programs, which aims to dissemination of a knowledge and an experience, to formation of a skills, a values, and a competence, in order to intellectual, spiritual and moral, creative, physical, and (or) professional development of individual, and to meet educational needs of individual. The manner, conditions and implementation modalities of outreach activity and also the procedure for the control of such activity are regulated by the Government of Russia. Outreach activity can be carried out by public and local authorities and natural and juridical persons concluded a contracts with educational institutions in the order determined by the Government of Russia. Although the Russian Academy of Sciences and numerous cultural and educational societies opposed the bill,[120][121][122] it was adopted by the State Duma, approved by the Federation Council and signed by President Putin.[123] According to scientists, science popularizers, educationalists, lawyers, this law, in fact, establishes the prior censorship of virtually every ways to share knowledge and conviction, contrary to the articles 19 and 29 of the Constitution of Russia.[124][125][126] According to the authors, the law aims to shield Russian citizens against anti-Russian propaganda.[127][128]

Fifth presidential term (2024–present)

Domestic policy

On 9 May 2000, the newspaper Kommersant had published the document called «Revision number Six», which was the reform project of Presidential Administration. Before the text of the document, editor-in-chief wrote: «the fact that such program is being developing is very important it is in itself ... if this will be a reality, almost of the entire population of Russia – from politicians and governors to ordinary voters – will be under surveillance by secret services».[129] This document was published again in 2010.[130]

Furthermore, on 9 May 2000, the newspaper Kommersant had published an article by deputy editor-in-chief Veronika Kutsyllo, according to which the text of «Revision number Six» had been provided to journalists by anonymous employee of the Presidential Administration; Putin was mentioned in the text of this document as acting president and the attached charts, totalling more than 100 pages, were drawn up before 1999 Russian legislative election, and these facts created the reason to believe that the work on this document started long before 2000 Russian presidential election.[131]

The authors of "Revision number Six" stated that Russian social and political system at the time was self-regulatory that was totally unacceptable to Putin who wished that all social and political processes in Russia were completely managed by one single body. The Presidential Administration and, more specifically, its Domestic Policy Directorate was to be such body.

The authors of «Revision number Six» rejected the possibility of direct prohibition on opposition activities and independent mass media activities considering that Russian society was not ready for that, and it was the reason, they proposed that Domestic Policy Directorate of the Presidential Administration uses the combination of public and secret activities. Secret activities were to be carried out with the direct use of special services, in particular, Federal Security Service.[132] The main objective of such secret activity was to take control over activity of political parties, community and political leaders, governors, legislatures, candidates for elective positions, election commissions and election officials, mass media and journalists. To achieve this objective, the following tasks were set: 1) the collection information (including dirt) about individuals and organizations of interests and the pressure on them; 2) the creation of conditions under which independent mass media cannot operate; 3) taking control over elections to ensure the victories of pro-Kremlin candidates; 4) the establishment of civil society organizations which are ostensibly independent but actually are under the full control of the Kremlin; 5) the discredit the opposition and the creation of the informational and political barrier around Putin (good things happen thanks to Putin personally but bad officials are responsible for bad things and not Putin; Putin does not respond to opposition's charge and does not participate in debates – others do that for him).

According to Vasily Gatov, the analyst of Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California, the realizations of the provisions of «Revision number Six» means building the state where democratic institutions exist nominally but in reality these institutions are fully controlled by Presidential Administration and secret police.[133] He characterized such regime as «counterintelligence state» (one of the kinds of guided democracy).[134][135]

On 7 May 2016, the newspaper Kommersant had published an article by Ilya Barabanov and Gleb Cherkasov containing an analysis of the implementation of provisions of «Revision number Six». They concluded that, although the authors of «Revision number Six» had not taken into account some things (for example, authors of the aforementioned document denied the need for creation of pro-Kremlin political party, which actually was established subsequently), by and large, the provisions of «Revision number Six» were conducted.[136]

Authoritarian bureaucratic state

Russian politician Boris Nemtsov and commentator Vladimir Kara-Murza define Putinism in Russia as "a one party system, censorship, a puppet parliament, ending of an independent judiciary, firm centralization of power and finances, and hypertrophied role of special services and bureaucracy, in particular in relation to business".[137]

Russia's nascent middle class showed few signs of political activism under the regime as Masha Lipman reported: "As with the majority overall, those in the middle-income group have accepted the paternalism of Vladimir Putin's government and remained apolitical and apathetic".[138]

In December 2007, the Russian sociologist Igor Eidman (VCIOM) categorized the Putin regime as "the power of bureaucratic oligarchy" which had "the traits of extreme right-wing dictatorship — the dominance of state-monopoly capital in the economy, silovoki structures in governance, clericalism and statism in ideology".[139]

In August 2008, The Economist wrote about the virtual demise of both Russian and Soviet intelligentsia in post-Soviet Russia and noted: "Putinism was made strong by the absence of resistance from the part of society that was meant to provide intellectual opposition".[140] In early February 2009, Aleksander Auzan, an economist and board member at a research institute set up by Dmitry Medvedev, said that in the Putin system "there is not a relationship between the authorities and the people through Parliament or through nonprofit organizations or other structures. The relationship to the people is basically through television. And under the conditions of the crisis, that can no longer work".[141] About the same time, Vladimir Ryzhkov pointed out that a bill Medvedev had sent to the State Duma in late January 2009, when signed into law, will allow Kremlin-friendly regional legislatures to remove opposition mayors who were elected by popular vote: "It is no coincidence that Medvedev has taken aim at the country's mayors. Mayoral elections were the last bastion of direct elections after the Duma cancelled the popular vote for governors in 2005. Independent mayors were the only source of political competition against governors who were loyal to the Kremlin and United Russia. Now one of the few remaining checks and balances against the monopoly on executive power in the regions will be removed. After the law is signed by Medvedev, the power vertical will be extended one step further to reach every mayor in the country".[142]

On 9 July 2020, the popular governor of the Khabarovsk Krai, Sergei Furgal, who defeated the candidate of Putin's United Russia party in elections two years ago, was detained and flown to Moscow. Furgal was arrested 15 years after the alleged crimes he is accused of. Every day since June 11, mass protests have been held in the Khabarovsk Krai in support of Furgal.[143] The protests included anti-Kremlin slogans like "Putin resign", "Twenty years, no trust", or "Away with Putin!".[144][145]

Human rights and repression

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (August 2022) |

On 7 April 2022, Russia was suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council over reports of "gross and systematic violations and abuses of human rights" after 93 members voted in favor.[146]

Pro-government propaganda and pressure on independent media

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (August 2022) |

On 1 March 2022, Russian authorities blocked access to Echo of Moscow and TV Rain,[147] Russia's last independent TV station.[148]

On 4 March 2022, Putin signed into law a bill introducing prison sentences of up to 15 years for those who publish "knowingly false information" about the Russian military and its operations, leading to some media outlets in Russia to stop reporting on Ukraine.[149]

Economic policies

On 9 July 2000, while speaking to the Russian Parliament, Putin advocated an economy policy[150] which would have introduced a flat tax rate of 13%[151] and a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 24 percent.[151] Putin also intended for small businesses to get better treatment under this economic reform package. Under Putin, the old system which included high tax rates has been replaced with a new system where companies can choose either a 6 percent tax on gross revenue or a 15 percent tax on profits.[151]

In February 2009, Putin called for a single VAT rate to be "as low as possible" (at the time it stood at an average rate of 18 percent), which could be reduced to between 12 percent and 13 percent.[152] The overall tax burden was lower in Russia under Putin than in most European countries.[153]

President Putin signed into law in 2024, a bill imposing a 13% progressive wealth tax for those earning up to 2.4 million rubles ($27,500) annually, a 22% income tax on those earning above 50 million rubles ($573,000), and a 5% increase on corporate taxes.[154] moving away from a flat tax.

Corporatism and state intervention in economy

According to Dr Mark Smith (March 2003), Putin had developed a "corporatist system" in the sense that under him the Kremlin was interested in close ties with business organizations such as the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, Delovaya Rossiya and the trade union federation (FNPR).[71] This was a part of Putins attempts to involve broad sectors of society in the making and implementation of policy.[71]

"There is a school of thought which says that a number of Putin's steps in the economy (notably the fate of Yukos) were signs of a shift toward a system normally described as state capitalism,[155][156][157] where "the entirety of state-owned and controlled enterprises are run by and for the benefit of the cabal around Putin—a collection of former KGB colleagues, Saint Petersburg lawyers, and other political cronies", he said in his words.[158]

According to Andrey Illarionov, advisor of Putin until 2005, Putin policies were a new socio-political order "distinct from any seen in our country before" as members of the Corporation of Intelligence Service Collaborators had taken over the entire body of state power, followed an omertà-like behavior code and were "given instruments conferring power upon others—membership "perks", such as the right to carry and use weapons". According to Illarionov, this "Corporation has seized key government agencies—the Tax Service, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Parliament, and the government-controlled mass media—which are now used to advance the interests of [Corporation] members. Through those agencies, every significant resource in the country—security/intelligence, political, economic, informational and financial—is being monopolized in the hands of Corporation members".[159] Members of the Corporation formed an isolated caste and according to an anonymous former KGB general cited by The Economist, "[a] Chekist is a breed ... A good KGB heritage—a father or grandfather, say, who worked for the service—is highly valued by today's siloviki. Marriages between siloviki clans are also encouraged.[160]

Jason Bush, chief of the Moscow bureau of the magazine Business Week has commented in December 2006 on troubling growth of government's role: "The Kremlin has taken control of some two dozen Russian companies since 2004 making them public property, including oil assets from Sibneft and Yukos, as well as banks, newspapers, and more. Despite his sporadic support for pro-market reforms, Putin has backed national champions such as energy concerns Gazprom and Rosneft. The private sector's share of output fell from 70% to 65% last year, while public owned companies now represent 38% of stock market capitalization, up from 22% a year ago".[161]

On 20 September 2008 and when the late 2000s recession had started to hit the well-being of Russia's top tycoons, the Financial Times said that "Putinism was built on the understanding that if tycoons played by Kremlin rules they would prosper".[162]

Although Russia's state intervention in the economy had been usually criticized in the West, a study by Bank of Finland's Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT) in 2008 showed that state intervention had had a positive impact on the corporate governance of many companies in Russia as the formal indications of the quality of corporate governance in Russia were higher in companies with state control or with a stake held by the government.[163]

Rising living standards

In 2005, Putin launched National Priority Projects in the fields of health care, education, housing and agriculture. In his May 2006 annual speech, Putin proposed increasing maternity benefits and prenatal care for women. Putin was strident about the need to reform the judiciary considering the present federal judiciary "Sovietesque", wherein many of the judges hand down the same verdicts as they would under the old Soviet judiciary structure and preferring instead a judiciary that interpreted and implemented the code to the current situation. In 2005, responsibility for federal prisons was transferred from the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Ministry of Justice.

The most high-profile change within the national priority project frameworks was probably the 2006 across-the-board increase in wages in healthcare and education as well as the decision to modernise equipment in both sectors in 2006 and 2007.[164]

During Putin's government, poverty was cut more than half.[34]

In 2006, chief of Business Week's Moscow bureau Jason Bush commented on the condition of Russian middle class: "This group has grown from just 8 million in 2000 to 55 million today and now accounts for some 37% of the population, estimates Expert, a market research firm in Moscow. That's giving a lift to the mood in the country. The share of Russians who think life is 'not bad' has risen to 23% from just 7% in 1999, while those who find living conditions 'unacceptable' has dropped to 29% from 53%, according to a recent poll". However, "[n]ot everyone has shared in the prosperity. Far from it. The average Russian earns $330 a month, just 10% of the U.S. average. Only a third of households own a car, and many—particularly the elderly—have been left behind".[161]

At the end of Putin's second term, Jonathan Steele has commented on Putin's legacy: "What, then, is Putin's legacy? Stability and growth, for starters. After the chaos of the 90s, highlighted by Yeltsin's attack on the Russian parliament with tanks in 1993 and the collapse of almost every bank in 1998, Putin has delivered political calm and a 7% annual rate of growth. Inequalities have increased and many of the new rich are grotesquely crass and cruel, but not all the Kremlin's vast revenues from oil and gas have gone into private pockets or are being hoarded in the government's "stabilisation fund". Enough has gone into modernising schools and hospitals so that people notice a difference. Overall living standards are up. The second Chechen war, the major blight on Putin's record, is almost over".[165]

Other economic developments and assessments

In June 2008, a group of Finnish economists wrote that the 2000s had so far been an economic boon for Russia, with GDP rising about 7% a year and by the beginning of 2008 Russia had become one of the ten largest economies in the world.[166]

In Putin's first term, many new economic reforms were implemented along the lines of the "Gref program". The multitude of reforms ranged from a flat income tax to bank reform, from land ownership to improvements in conditions for small businesses.[166]

In 1998, over 60% of industrial turnover in Russia was based on barter and various monetary surrogates. The use of such alternatives to money now today fallen out of favour, which has boosted economic productivity significantly. Besides raising wages and consumption, Putin's government has received broad praise also for eliminating this problem.[166]

In the opinion of the Finnish researchers, the most high-profile change within the national priority project frameworks was probably the 2006 across-the-board increase in wages in healthcare and education as well as the decision to modernise equipment in both sectors in 2006 and 2007.[166]

The rise in the overall living standards further deepened Russia's social and geographical discrepancies. In July 2008, Edward Lucas of The Economist wrote: "The colossal bribe-collecting opportunities created by Putinism have heightened the divide between big cities (particularly Moscow) and the rest of the country".[167][168]

In November 2008, the retired KGB lieutenant-general Nikolai Leonov, in assessing the overall results of Putin's economic policies for the period of 8 years, said that [w]ithin this period, there has only been one positive thing, if you leave aside the trivia. And that thing is the price of oil and natural gas".[169] In the closing paragraphs of his 2008 book, the retired general said: "Behind the gilded facade of Moscow and Saint Petersburg, there lies a demolished country that, under the current characteristics of those in power, has no chance to restore itself as one of the developed states of the world".[170][171]

On 29 November 2008, Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party of Russian Federation (the largest opposition group within Russia with its 13% of seats in the national Parliament), in his speech before the 13th Party Congress lamented that due to "heroic efforts" of the "Yeltsinites" the country has lost 5 out of the 22 million square kilometers of its "historical territory" and that Russia faces de-industrialization, de-population and mental debilitation. The ruling group has in his opinion no notable successes to boast of, no clear plan of action and is only focussed on staying in power at all costs.[172]

To characterize the kind of state Putin had built in socio-economic terms, in early 2008 professor Marshall I. Goldman coined the term "petrostate" in Petrostate: Putin, Power, and the New Russia,[173] where he inter alia argued that while Putin had followed the advice of economic advisers in implementing reforms such as a 13 percent flat tax and creating a stabilization fund to lessen inflationary pressure, his main personal contribution was the idea of creating "national champions" and the renationalization of major energy assets. In his June 2008 interview, Marshall Goldman said that in his opinion Putin had created a new class of oligarchs, whom some called "silogarchs", Russia having come in second in the Forbes magazine list of the world's billionaires after only the United States.[174]

In December 2008, Anders Åslund pointed out that Putin's chief project had been "to develop huge, unmanageable state-owned mastodons, considered "national champions"", which had "stalemated large parts of the economy through their inertia and corruption while impeding diversification".[175]

People are new oil

On 14 November 2016, Elvira Nabiullina, the head of Central Bank of Russia, stated that "the previous model which based upon exporting raw materials and stimulating consumption, including through consumer lending, has been exhausted; this was manifested in «the fading of the rates of economic growth before the crisis and the drop in oil prices".[176]

Russian economist Dmitriy Prokofiev believes that the new economic model of Putin's Russia is based on the same principles that were used during the Stalin's five-year plans. The essence of this system is to provide investment in large projects under the patronage of the government and guarantee the income of the political and economic elite by direct and indirect uptake of money from the population. As a result of cheap labour and expensive capital policy, economic entities use labour-based and not capital-intensive technologies. At the same time, the impoverishment of the population and the decrease of the domestic consumer demand forces economic entities to seek objects for investment outside Russia. That is why the profits of large companies and their owners do not affect the income of individuals.[177]

New economic model was named «People are new oil». This phrase entered the lexicon of Russian bureaucrats believing that citizens are the source of income and benefits, but not an object of concern and care.[178]

The particular manifestations of the new economic model are the following: freezing of the funded part of the pension from 2014 until at least the end of 2023,[179] raising the retirement age,[180] value added tax rate hike,[181] income tax on natural persons rate hike,[182] reviving the Stalin's practice of using the prisoner's labour.[183]

Since 2013, the incomes of Russian residents are declining for eight years in a row.[184]

Foreign policy

In June 2000, Putin's decree was approved by the "Concept of the Russian Federation's foreign policy". According to this document, the main objectives of foreign policy are the following:

- Ensuring reliable security of the country.

- The impact of global processes in order to create a stable, just and democratic world order.

- The creation of favorable external conditions for the onward development of Russian.

- Formation of the Neighbourhood zone around the perimeter of the Russian borders.

- Search agreement and coinciding interests with foreign countries and international associations in the process of solving problems, Russia's national priorities.

- Protecting the rights and interests of Russian citizens and compatriots abroad.

- Promote a positive perception of the Russian Federation in the world.

On 10 February 2007, Putin delivered a confrontational speech in Munich where, inter alia, he accused the West of breaking the promise not to expand NATO into new countries in Eastern Europe believing that is a threat to Russia's national security. According to John Lough, associate fellow of the Chatham House, Putin's statement was based on the myth that the West deceived Russia by reneging on its promises at the end of the Cold War not to enlarge NATO and chose to pass up the opportunity to integrate Russia into a new European security framework and instead encouraged Moscow back on to a path of confrontation with the United States and its allies. In fact, the Soviet Union neither asked for nor was given any formal guarantees that there would be no further expansion of NATO beyond the territory of a united Germany and, in addition, the Soviet Union signed the Charter of Paris in November 1990 with the commitment to 'fully recognize the freedom of States to choose their own security arrangements'.[185] In opinion of Andrey Kolesnikov, senior fellow of the Carnegie Moscow Center, this speech was the "foul of the last hope": Russian president wanted to scare the West with his frankness believing that, perhaps, "western partners" would take into account his concerns and make several steps forward to meet him. It had a reverse effect but this scenario was also calculated: either you will or you will not, Russia will be transforming from the fragment of the West into the super-sovereign island. Seeing as what happened thereafter, he decided for himself that he is free in his actions: because he had not succeeded in becoming a world leader by western rules, he would become a world leader by his own rules.[186]

In a 2010 article in the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung dedicated to the participation in the annual economic forum, it was proposed to create a European economic alliance stretching from Vladivostok to Lisbon. As steps towards the creation of the alliance indicates a possible unification of customs tariffs and technical regulations, the abolition of the visa regime with the European Union.[187]

In August 2013, according to experts the Russian-American relations have reached their lowest point since the end of the Cold War era. The September President Barack Obama's visit to Moscow and his talks with Putin were canceled due to temporary asylum in Russia, a former employee of the CIA Edward Snowden, disagreements on the situation in Syria and the problems with human rights in Russia.[188] Russia has a long history of Anti-Americanism, dating back to the early days of the Cold War. In some of the latest Russian population polls, the United States and its allies consistently top the list of greatest enemies.[189][190] Survey results published by the Levada-Center indicate that, as of August 2018, Russians increasingly viewed the United States positively following the Russia–U.S. summit in Helsinki in July 2018.[191] But only 14% of Russians expressed net approval of Donald Trump's policies in 2019.[192] According to the Pew Research Center, "57% of Russians ages 18 to 29 see the U.S. favorably, compared with only 15% of Russians ages 50 and older."[193]

On 11 September 2013, The New York Times published an article by Putin, "Russia calls for caution". It is written in the form of an open letter to the American people, containing an explanation of the Russian political line against the Syrian conflict. It is also the Russian president warns against President Obama's thesis "About the exclusivity of the American nation". The article caused a mixed reaction of the world community.[194]

In 2013, Putin won the first place in the annual ranking of most influential people in the world by Forbes.[195] In 2014, the result was the same.[196]

On 18 March 2014, Vladimir Putin gave the Crimean speech. Many Russian and foreign public figures compared this speech to Hitler's speech on Sudetenland from 1939 as using "the same arguments and vision of history".[197][198] Pro-Kremlin politologist Andranik Migranyan opposed to the position of the historian Andrey Zubov[199] and stated that there was a difference between Adolf Hitler before 1939 and Hitler after 1939, and after the annexation of Crimea Putin should be compared with "good Hitler".[200]

On 24 October 2014, Vladimir Putin made the Valdai speech in which he accused the United States of undermining the world order[201] and predicted that the clash would not be the last to pit Russia and the United States against each other.[202] Putin threatened "sharp increase in the likelihood of a whole set of violent conflicts with either direct or indirect participation by the world's major powers" including those arising from "internal instability in certain countries" "located at the intersections of major states’ geopolitical interests, or on the border of cultural, historical, and economic civilizational continents", citing the example of Ukraine[203] and warning that this example "will certainly not be the last".[204]

In September 2015, Putin spoke at the United Nations General Assembly session in New York City for the first time in 10 years. In his speech, he urged the formation of a broad anti-terrorist coalition to combat ISIS and blamed the events in Ukraine on "external forces", warned the West against unilateral sanctions, attempts to push Russia from the world market and export of color revolutions. For the first time, he also held a meeting with President Obama to discuss the situation in Syria and Ukraine, but in the outcome of the negotiations and despite the persistence of deep contradictions the experts saw a faint hope for a compromise and the warming of relations between the two countries.[205]

In September 2015, Vladimir Putin sent Russian troops in Syria supporting Bashar al-Assad in his war against Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, Al-Nusra Front and also Syrian opposition militant groups opposed to the Syrian government.[206][207][208][209][210] Wagner Group, affiliated to Putin's close circle and tacitly coordinated by GRU, was also used in the war against Assad's opponents.[211][212][213]

Putin supported Nicolás Maduro in Venezuelan presidential crisis[214] and sent Russian troops led by the chief of Staff of the Russian Ground Forces Colonel General Vasily Tonkoshkurov to Caracas.[215]

On 29 August 2020, Vladimir Putin stated that Russia accepts the election result of Belarusian presidential election and recognizes Alexander Lukashenko as legitimate President of Belarus.[216] Earlier, in mid-August 2020, there were reports that several dozen trucks, identical to the ones used by the National Guard of Russia, without registration plates and any marks, were sighted in Smolensk Oblast and Pskov Oblast heading toward Belarusian border. In Conflict Intelligence Team assessment, these trucks could carry no less than 600 soldiers.[217] Kremlin did not confirm the sending Russian troops to Belarus, said that events in Belarus did not yet warrant Russia's military involvement and condemned alleged foreign interference in Belarus's affairs by Western countries against the backdrop of mass protests in Belarus.[218] Hans van Baalen considered that Russian intervention in Belarus is already a fact.[219]

State-sponsored global public relations effort

Shortly after the Beslan terror act in September 2004, Putin enhanced a Kremlin-sponsored program aimed at "improving Russia's image" abroad.[220] According to an unnamed former Duma deputy, there existed a classified article in the RF federal budget that provided for financing measures to this purpose.[221]

One of the major projects of the program was the creation in 2005 of Russia Today—a rolling English-language TV news channel providing 24-hour news coverage, modeled on CNN. Towards its start-up budget, $30 million of public funds were allocated.[222][223] A CBS News story on the launch of Russia Today quoted Boris Kagarlitsky as saying it was "very much a continuation of the old Soviet propaganda services".[224] In 2007, Russia Today employed nearly 100 English-speaking special correspondents worldwide.[225]

Russia's deputy foreign minister Grigory Karasin said in August 2008 in the context of the Russia-Georgia conflict: "Western media is a well-organized machine, which is showing only those pictures that fit in well with their thoughts. We find it very difficult to squeeze our opinion into the pages of their newspapers".[226] Similar views were expressed by some Western commentators.[227][228]

William Dunbar, who was reporting then for Russia Today from Georgia, said he had not been on air since he mentioned Russian bombing of targets inside Georgia on 9 August 2008 and had to resign over what he claimed was biased coverage by the outlet.[226][229]

The public relations efforts notwithstanding, according to an opinion poll released in February 2009 by the BBC World Service, Russia's image around the world had taken a dramatic dive in 2008: forty-two percent of respondents said they had a "mainly negative" view of Russia, according to the poll, which surveyed more than 13,000 people in 21 countries in December and January.[230]

In June 2007, Vedomosti reported that the Kremlin had been intensifying its official lobbying activities in the United States since 2003, among other things hiring such companies as Hannaford Enterprises and Ketchum.[231]

In the 2012 Moskovskiye Novosti magazine article "Russia and changing world",[232] Putin directly stated that Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation and Russkiy Mir Foundation are Russia's international lobbying tools.

In accordance with 26 Article of Federal Law of 24 May 1999, No.99-FZ, Worldwide Congress of Compatriots is the highest body that ensures interaction between Russian compatriots and Russia's authorities; in the inter-Congress period, the executive functions in the sphere of interaction between Russian compatriots and Russia's authorities are carried out by Worldwide Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots.[233]

International Council of Russian Compatriots is another organization that unify different movements of Russian émigrés. International Council of Russian Compatriots was founded after the congress with the participation of Vladimir Putin, which was held in 2001.

In opinion of Dmitry Khmelnitsky, Soviet and German architect and historian, the Russian network of agents of influence abroad is extraordinarily broad and differentiated. It consists of a multitude of organizations created and financed by Moscow and under social groups and simulating social, cultural and scholarly activity. Some of these organizations are directed at the local communities, others at émigrés from the Soviet Union and Russia, although sometimes both these tasks are addressed by one and the same organizations. Their classification by itself is worthy of attention because under this format, the Russian special services work in all the countries of the world. Since Vladimir Putin came to power, Moscow has created several major and many minor organizations to work with Russian and Soviet emigres. Among the most important are the International Council of Russian Compatriots, the Worldwide Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots Living Abroad, the Worldwide Congress of Russian-Speaking Jewry and the Russkiy Mir Foundation, a pass-through funding group which now operates more than 200 Russian centers around the world. But it is only the tip of the iceberg.[234]

The Russian network of agents of influence in Western countries included even military-patriotic camps where Russian-speaking youth received military training.[235][236] The activity of the one of such camps caused a scandal in Serbian society.[237] Some pro-Kremlin Russian diaspora organizations are under the investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[238]

Militarism and wars outside Russian territory

Russian Armed Forces underwent various reforms during Putin's rule. The first reform was announced by minister of defence Sergei Ivanov in 2001 and was completed in 2004. As a result of the reform, constant combat readiness military units, staffed with volunteers only, appeared in Russia but draft system had been retained.[239] As of 2008, there were 20% constant combat readiness military units, manned to wartime standards, and 80% cadre military units, manned to peacetime standards, in Russian Armed Forces.[240]

After the Russo-Georgian War, it became clear[according to whom?] that Russian military organization needed further reform; as Vladimir Shamanov said, cadre regiments and divisions, intended for receiving mobilization resources and deployment in the period immediately preceding the outbreak of war, have become a costly relic.[241] On 14 October 2008, minister of defence Anatoly Serdyukov announced the beginning of new reform.[242] The main organizational change was the transition from a 4-level operational chain of command (Military District – Army – Division – Regiment) to a 3-level one (Military District – Operational Command (Army) – Brigade).[243] Also Russia fully refused cadre military units, manned to peacetime standards (so-called "paper divisions"), and since that times only constant combat readiness military units, 100% manned up to wartime standards, were part of Russian Armed Forces.[244] On 31 October 2010, Anatoly Serdyukov stated that changes in organizational-regular structure was completed.[245]

According to Alexander Golts, journalist and military columnist, as a result of aforementioned reforms, Russia gained absolute military dominance in the post-Soviet area and Russian Armed Forces gained the ability that it had never had: ability to quick deployment, which was clearly demonstrated on 26 February 2014.[247]

Some military experts[which?] mentioned that since the Annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russia organized many new military units and formations without a significant increase in the number of volunteers and conscripts, prompting them to consider these units "paper divisions".[248][249][250] However, in 2018, Russia began to form a military reserve force staffed by volunteers selected from among retired active duty soldiers.[251] Reservists serve in conventional military units; thus, reserve units are staffed to wartime standards and are therefore indistinguishable from regular units. The number of reservists is not made available to the public in open sources or from the Ministry of Defence. This makes it difficult for establish real troop strength of new Russian military formations.[citation needed]

According to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia had been in the top 5 military spenders since 2006, except 2018, and Russia's military expenditure reached $61.7 billion in 2020.[252] In RBK assessment, based on 2017 Federal State Statistics Service data, budget expenditures, classified as state secret, reached 5,3% of gross domestic product.[253] In 2021, the 15% of budget expenditures are classified as state secret.[254]

In Andrey Piontkovsky's opinion, Putin feels frustration towards the Soviet Union's defeat in the Cold War — which Piontkovsky calls a "Third World War" — and seeks to defeat the West in a "Fourth World War." In fact, Putin has started this war in 2014[speculation?] with annexation of Crimea, more specifically since 20 February 2014 – this date is specified in the Medal "For the Return of Crimea".[255] Piontkovsky believes that geopolitical thinking of Putin and his close circle was reflected in the 2018 "Zavtra" magazine article by Alexander Khaldey:[256][relevant?]

Some American real colonel said that Russia believes in vain that it will serve the purposes of de-escalation of tension if Russia will use nuclear weapon. Russia is wrong. Nuclear weapon usage will not serve the purposes of de-escalation, Moscow will not achieve its goals like that.

I'm not diplomat and therefore I'll be blunt – we don't seek the de-escalation AFTER nuclear weapon usage, we seek the de-escalation BEFORE nuclear weapon usage. AFTER nuclear weapon usage, we'll just ruin you along with the rest of the world. Herein lies our goal of nuclear weapon usage. So say whatever you want but not even try.