Russia for Russians

"Russia for Russians" (Russian: Росси́я для ру́сских, Rossiya dlya russkikh, Russian pronunciation: [rɐˈsʲijə dʲlʲɪ ˈruskʲɪx]) is a political slogan and nationalist doctrine, encapsulating the range of ideas from bestowing the ethnic Russians with exclusive rights in the Russian state to expelling all ethnically non-Russians from the country. Originated in the Russian Empire in the latter half of the 19th century, the slogan has become increasingly popular in modern Russia,[1][2][3][4] challenging the dominant discourse of multiculturalism within Russia.[5]

Russian Empire

[edit]Origin

[edit]The original "Russia for Russians" idea has variously been ascribed to a Black Hundreds ideologue Vladimir Gringmut, to General Mikhail Skobelev (1843-1882), or to Tsar Alexander III of Russia (1845-1894). Gringmut authored one of the first publications to use the slogan. He proclaimed "Russia for Russian" as a slogan of the Russian Monarchist Party, which, he wrote,

"clearly sees that if Russia is left to the people of alien stock and religion, and to foreigners, – not only will not be the Autocracy, but Russia herself."

Another version attributes the notion to Alexander III, who declared that

"Russia should belong to Russians, and all others dwelling on this land must respect and appreciate this people".[citation needed]

According to General Aleksey Kuropatkin, Alexander chose "Russia for Russians" as his watchword. General Skobelev is also reported to have said that

"I want to inscribe on my banner: 'Russia for Russians and in a Russian way,' (Russian: Россия для русских и по-русски) and raise this flag as high as possible!"[6][7]

In the last decades of the 19th century, some Russian political movements proposed reclassifying "Russia" as an ethnic or even as a racial category. They advocated "Russia for Russia" and believed that Russians deserved more rights than other nationalities in their "own empire" as they had established and maintained the state in the first place. Such exclusive nationalists denounced non-Russians as grossly ungrateful for the benefits they had received from Russian rule.[8] Although these sentiments caught the minds of some intellectuals in the latter part of the 19th century, right-wing xenophobic organizations originated during the Russian Revolution of 1905, when political parties were finally legalized. They made "Russia for the Russians" their battle cry, yet were determined to preserve "one and united Russia" through the Russification of the non-Russians.[9] The first hostile "other" to be targeted were the Jews, and "Russia for Russians" was soon augmented with the slogan "Beat up the Yids and save Russia!".[10]

Criticism

[edit]From the beginning, the slogan and the idea of the empire ruled by Russians was controversial regarding what "Russians" meant. One of the outspoken critics of the notion, Pavel Milyukov, leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party, considered the "Russia for Russians" slogan to have been "a slogan of disunity… [and] not creative but destructive."[11] In 1909, Milyukov addressed the Russian State Duma on the issue of using Ukrainian in the court system, attacking Russian nationalist deputies:

"You say 'Russia for Russians,' but whom do you mean by 'Russian'? You should say 'Russia only for the Great Russians,' because that which you do not give to Muslims and Jews you also do not give your own nearest kin – Ukraine."[12]

Another notable politician, Prime Minister Sergei Witte, warned Tsar Nicholas II against his flirtation with these ideas because it would disrupt the delicate ethnic balance in the Russian state.[10] The slogan was also rejected by the moderate nationalist Nikolai Berdyaev who viewed it as "pagan nationalism" and contrasted it with the messianist "Christian nationalist" notion "Russia for the World."[13]

Opposition from protagonists of a multi-ethnic empire like Witte and indifference of most Russian workers and peasants of pre-World War I Russia to such sentiments rendered the project of a Russian ethnocracy abortive without even being properly launched.[10]

Modern Russia

[edit]

The notion "Russia for Russians" resurfaced again later in the 1980s when the ultra-nationalist Pamyat staged a series of demonstrations and passed out handbills that read "Russia for Russians!" and "Death to the Yids!".[17]

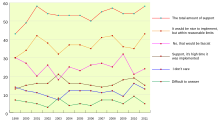

With the outbreak of a second war in Chechnya in 1998 and growing antipathy to "strangers" in Russia after Vladimir Putin's advent to power, the proportion of those who subscribe to the maxim "Russia for Russians" began to increase, partly as a reaction to the crisis and instability and uncertainty of the 1990s as well as growing public discontent with the influx of migrants from Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and China. Thus, the overall number of its supporters rose from 46% in 1998 to 58% in 2005.[1][18][19] By "Russians", the respondents frequently mean exclusively ethnic Russians, and preferably with a "Slavic face" appearance, not Russian citizens.[20][21] This slogan has become a prominent feature at nationalist manifestations during the annual Unity Day holiday.[22] The victims of ethnic and racial violence also reported hearing chants of "Russia for Russians" during attacks.[23][24][25]

In 2003, during a television broadcast with President of Russia, Russians on the streets asked him questions. One of the elderly men asked Vladimir Putin what his and his party's stance on "Russia for Russians" slogan was. Putin responded that those who shout and act upon such slogan are "either idiots or provocateurs" (придурки либо провокаторы), who "don't understand what they do and shout". Putin also mentioned that such people want to weaken the Russian Federation, composed of many nations and cultures, by inciting racial and national hatred which ultimately would lead to the Federation's dissolution. Putin also warned that the law enforcement agencies should act as soon as possible against such people who threaten public order.[26]

In a 2006 opinion poll published by the independent Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM), 34% of the respondents approved the slogan on the proviso that by "Russians" is meant all citizens of the Russian Federation, 23% said they would not object to the idea if implemented within "reasonable limits", 20% (mostly in Moscow and St. Petersburg) believed the realization of this concept – without any restrictions – was long overdue. The notion was disapproved of by 23%, of whom 12% feared difficulties with the West, and 11% of whom described it as "true fascism". At the same time, supporters of the slogan diverged regarding what "Russians" meant – all those who had been brought up in Russian traditions (39%), those who labored for Russia (23%), only Russians "by blood" (15%), those who spoke Russian as a native language (12%), or Russian Orthodox Christians (7%).[27]

Human rights groups have implicated the sentiment as translating into violence against foreigners.[28] Alexander Brod, director of the Moscow Bureau for Human Rights (MBHR), has argued that polling data indicate that 60% of Russia's adult population adheres to an ideology he has described as "Russia for Russians and all misfortune is from non-Russians." Lyudmila Alexeyeva, chairwoman of the Moscow Helsinki Group, has accused the top Russian officials of promoting the notion. She cited as an example Krasnodar governor Aleksandr Tkachyov, who has vowed to drive "the aliens and dissenters" out of his region.[29] The MBHR published, in 2005, a report monitoring xenophobia during the Moscow local elections and argued that a number of political parties adhered to xenophobic slogans, such as "Russia for Russians" and "Russian faces in the Russian capital", in their election campaigns.[30] For example, the Rodina party and its leader Dmitry Rogozin made illegal immigration and a "Moscow for Muscovites!" platform a centerpiece of their election campaign.[31]

An investigation ordered by a Russian court concluded that slogan "Russia for Russians" does not fuel ethnic hatred.[32] The investigation was conducted in connection with a case of assaulting a Caucasian teenage migrant from Dagestan who was almost killed near his school. The attackers shouted "Russia for Russians!",[33] while beating the boy.

On 28 July 2010, a court in Russia demanded an ISP block access to YouTube because the site hosted "Russia for Russians", which is considered by many to be an extremist video.[34]

A 2016 Levada Center poll on the question on Russia for Russians, found that 14% supported I support it, it's high time to implement it. A further 38% said, It would be nice to implement it, but within reasonable limits (Total support 52%). While 21% opposed it, saying this is real fascism.[35]

A 2020 Levada Center poll found The level of support for the idea " Russia for Russians " at 20% with "I support, it's time to implement" 32% said "good, but within reasonable limits" *Total support 52%), and 28% opposed saying "negative, this is real fascism ". 15% said " I'm not interested".[36]

In 2021, Putin called the slogan of "cave nationalism".[37][38][39]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gudkov, Lev (2005), Xenophobia: Past and Present. Nezavisimaya Gazeta/Republished in "Russia in Global Affairs". № 1, January – March 2006.

- ^ Zarakhovich, Yuri (2006-08-23), Inside Russia's Racism Problem. Time (magazine).

- ^ Charny, Semyon. Xenophobia, migrant-phobia and radical nationalism at the elections to the Moscow City Duma Review of the Moscow Bureau for Human Rights. Antirasizm.ru – Moscow Bureau for Human Rights.

- ^ Alexseev, Mikhail A. (December 2005), Xenophobia in Russia: Are the Young Driving It?. PONARS Policy Memo No. 367. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- ^ Shlapentokh, Dmitry (November 9, 2006). "Two sides of the Georgia-Russia conflict". www.watchdog.cz.

- ^ (in Russian) Ivanov, A. (September 2007). «Россия для русских»: pro et contra. Tribuna rosskoi mysli № 7. Retrieved from rusk.ru

- ^ Rawson, Don C. & Richards, David (1995), Russian Rightists and the Revolution of 1905, p. 52. ISBN 0-521-48386-7.

- ^ Tuminez, Astrid S. (2000), Russian Nationalism Since 1856, p. 127. Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-8476-8884-4.

- ^ Timothy Baycroft, Mark Hewitson (2006), What is a Nation?, p. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-929575-1.

- ^ a b c Eric P. Kaufmann (2004), Rethinking Ethnicity: Majority Groups and Dominant Minorities, pp. 138-9. Routledge, ISBN 0-415-31542-5.

- ^ Kirschke, Melissa (1996), Paul Miliukov and the quest for a liberal Russia, 1880-1918, p. 189. Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-3248-0.

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2005), Unmaking Imperial Russia: Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Writing of Ukrainian History, pp. 462-3, n. 64. University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-3937-5.

- ^ (in Russian) Pustarnakov, V.F. (200), Университетская философия в России, p. 201. Directmedia Publishing, ISBN 5-88812-184-3.

- ^ Snetkov, Aglaya; Pain, Emil; Foxall, Andrew; Galiullina, Galima (10 March 2011). Aris, Stephen; Neumann, Matthias; Orttung, Robert; Perović, Jeronim; Pleines, Heiko; Schröder, Hans-Henning (eds.). "Russian Nationalism, Xenophobia, Immigration and Ethnic Conflict" (PDF). Russian Analytical Digest (93). ETH Zurich. ISSN 1863-0421. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ Национализм в современной России [Nationalism in contemporary Russia] (in Russian). Levada Center. 4 February 2011. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Lee, Martin A. (1999), The Beast Reawakens, p. 306. Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-92546-0.

- ^ Lipsky, Andrei (2008-09-03), Photofit of the Russian average citizen: Xenophobia. Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved from rusk.ru

- ^ Sapozhnikova, Galina (2008-04-29), Hate crimes in Russia: Citizens of former Soviet republics fear Russia's streets – Part 2. Komsomolskaya Pravda.

- ^ Umland, Andreas (21 August 2008). A Shield of a Passport. Russia Profile.

- ^ Zarakhovich, Yuri (2004-08-01), From Russia With Hate. Time.

- ^ Schlindwein, Simone (2007-05-11), Neo-Nazis on the march in Moscow. Spiegel Online.

- ^ Jackson, Patrick (2006-02-24), Living with race hate in Russia. BBC News.

- ^ St. Petersburg, Russia: 2006 Crime and Safety Report. Overseas Security Advisory Council. 2006-06-08.

- ^ LeGendre, Paul (2006-06-26), Minorities Under Siege. Hate Crimes and Intolerance in the Russian Federation. Human Rights First.

- ^ "Путин:"Россия для русских-говорят придурки либо провокаторы"" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ (in Russian) Россия для русских или для всех?. VCIOM Press-release № 603. 2006-12-21.

- ^ Bigg, Claire (2005-10-25), Russia: Hate Crime Trial Highlights Mounting Racism. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ Gurin, Charles (2004-10-27), Russian media mulls growing ethnic intolerance. Eurasia Daily Monitor, Volume 1, Issue 114.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (2005-11-27), Foreign students scared to leave their homes after stabbings in St Petersburg. The Independent.

- ^ Ivanov, Eugene (2005-10-17), The rise and fall of President Putin’s “spetsnaz”. Russia Profile.

- ^ Russian Original of the conclusion by expert Kirukhina

- ^ Echo of Moscow

- ^ O'Dell, Jolie (July 29, 2010). "YouTube Banned in Russia Over Racist Video". Mashable.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]